Features

Origins and growth of Janatha Vimukthi Peramuna

THE APRIL 1971 REVOLT – I

By Jayantha Somasundaram

The 50th anniversary of the first JVP insurrection falls today. The 1971 rebellion was the first armed uprising against the state in modern times.

The JVP was the brainchild of Rohana Wijeweera. Born in 1943, at Hunandeniya, in the Matara District, his father was a supporter of the Communist Party of Ceylon (CPC). However, while studying medicine in Moscow, Wijeweera became critical of the Soviet Union, and, on his return, he joined the Communist Party (CP), which was Maoist. Not long after, in 1966, Wijeweera, along with his supporters, broke ranks with the CP to form their own movement, which would later become the JVP. Wijeweera had concluded that the agricultural labourer -̶ the rural proletariat -̶ was the largest and most important component of Sri Lanka’s working class, not the urban or plantation worker.

The JVP was able to attract university students to its cause. It gained recruits at Vidyalankara (Kelaniya) University by winning over students who were members of the PC-supporting Lanka Jatika Sishya Sangamaya (Lanka National Students Society) led by G. I. D. ‘Castro’ Dharmasekera. In 1970, the JVP wrested control of the Samajawadi Sishiya Sangamaya (the Socialist Students Society) at the Peradeniya University; while on behalf of the JVP, Mahinda Wijesekera led the Sangamaya at Vidyodaya (Sri Jayewardenepura) University.

In 1969, Wijeweera organised two Congresses, bringing together all his supporters. At the two-day conference in Madampella, Negombo, the leadership, which consisted of Wijeweera, Sanath, Karunaratne and Loku Athula, along with the District Secretaries, constituted the JVP Central Committee. Later that year, at Urubokka, in the Matara District, the movement took on its final configuration. Five-member cells formed the core structure, overseeing them would be area leaders who were in turn responsible to District Secretaries.

At the Urubokka Conference, the prospect of manufacturing weapons was taken up and the suggestion made that projectiles such as rockets would be effective against the Army’s Panagoda Cantonment, at Homagama. In early 1970, at the Dondra Conference, in addition to collecting and manufacturing weapons, the details of recruitment, training, uniforms, and collecting information on the Armed Forces, were discussed.

The JVP’s Ideology

The JVP was critical of the mainstream left parties, the Lanka Sama Samaja Party (LSSP) and the Communist Party as they had entered into an alliance with the Sri Lanka Freedom Party (SLFP) and would be constituents of the United Front (UF) government, which came to power in May 1970. However, it was in those very areas, that had been worked on by the older left parties for three decades, that the JVP took root.

The JVP leaders, however, were from backgrounds and experiences quite different from that of the old left parties. They did not come from Colombo’s public schools, few of them had been to the British-styled residential university at Peradeniya, and none to Western universities. Many were teachers and students of small-town Central Schools and the Pirivena (Buddhist monastic) Universities. “Unlike the traditional left, the activists of the JVP were the children of the 1956 Sinhala-only struggle, with its attendant limitations and advantages,” writes Michael Cooke in Rebellion, Repression and the Struggle for Justice in Sri Lanka: The Lionel Bopage Story.

The rank and file of the JVP consisted of militant Sinhala-educated young men and women. They were underprivileged rural youth, with meagre job opportunities, constituting a potential army of frustrated school and university leavers. Overwhelmingly Buddhist Sinhalese, they were drawn from marginalised castes. Wahumpura villages in Elpitiya gave the JVP strong support, while, in Kegalle, the Batgam were won over by the JVP. In Sri Lanka: Third World Democracy, James Jupp explains: “The JVP appealed to the Buddhist Karawe, Durawe, Batgam, Wahumpura … both from the Southern Province and the Kegalle District, anti-Govigama feeling was a motive behind the mass recruitment to the JVP in certain villages.”

The JVP endeavoured to recruit sympathisers in the armed forces, with Wijeweera establishing contact, as early as 1965, with Tilekaratne, a rating in the Royal Ceylon Navy. Later Uyangoda held classes for Naval personnel, made contact with Air Force personnel in Wanathamulla and Katunayake, and delivered lectures to them. They also provided classes for soldiers stationed at Diyatalawa.

The Party evolved its own Marxist ideology which was a hybrid. It drew on Trotsky’s criticism of Stalinism and the ‘popular front.’ From Mao it asserted the primacy of the peasantry as the backbone of the revolution. And from Castro it learnt armed insurrection. The JVP training for its cadres emphasised neo-colonialism, attacked parliamentarianism and rejected the mainstream left parties.

In its economic teaching, the JVP differed little from the LSSP or CP. However, they did not only point out the neo-colonial dependence of Sri Lanka’s economy, but identified the UF as part of this neo-colonial system. They called for a halt to the expansion of the tea plantations while advocating the intense cultivation of food crops and the collectivisation of land to overcome landlessness. The JVP in its propaganda organ Vimukthi claimed that “the socialist revolution would succeed in Ceylon only when the oppressed peasantry became politicised … hey are the moving force of the Ceylonese revolution.”

Political Growth

The JVP recruited cadres who would attend political training, delivered through five lectures. These covered the economic crisis, neo-colonialism, Indian expansionism, the left movement and the Sri Lanka revolution. Those who completed all five lectures and volunteered for combat, around 9,000, had military training.

It was in tactics, however, that the JVP differed radically from the rest of the left, which had been concerned with trade unions, strikes, rallies and elections. With the passage of time, the JVP evolved a tactic, where they functioned openly as an agitational group, whilst, at the same time recruiting combatants into a clandestine military organisation. They held that the socialist revolution in Sri Lanka would have to be a sudden armed insurrection, launched simultaneously across the country. This is the most advanced and complex form of revolutionary combat.

Their ‘24-Hour Revolution’ was premised on the assumption that the police and the armed forces had insufficient ammunition to survive a simultaneous uprising throughout the country. However they also wrestled with a critical tactical dilemma: “How to attack the government, moving carefully enough not to outpace the disillusion of the masses, yet fast enough to hit before the government struck at it.” (Fred Halliday The Ceylonese Insurrection in Explosion in a Sub Continent edited by Robin Blackburn)

The JVP came into the open, in 1969, through public meetings, the first of which was held at Vidyodaya University. This public profile brought a large number of new recruits whom the leadership claim reached about 23,000 committed members. But it also resulted in the police responding with widespread arrests amounting to about a thousand JVP activists. Fearing all out repression, they established protected villages in remote rural areas, as logistical bases. “The movement took no root in the towns, nor in the industrial coastal areas around Colombo, nor in the Tamil areas,” wrote the Belgian Catholic priest and sociologist Francois Houtart in Religion and Ideology in Sri Lanka.

Shortly before the May 1970 general election, Dharmasekera allegedly informed the Minister of State J. R. Jayewardene, through an intermediaries, of the JVP threat. This triggered heightened interest in the media which gave them the appellation ‘Che Guevarists,’ and the establishment of a special CID Unit, which began arresting JVP members. Wijeweera himself was arrested at Hambantota on 12th May. When he was released in July, Wijeweera launched a series of public meetings across the country, going as far north as Anuradhapura. There was a pause after October and then came a massive meeting in Colombo at Hyde Park on 27 February 1971.

The Prelude to the Uprising

The JVP’s highest decision-making body was its 12-person Political Bureau (PB) which, at its Ambalangoda meeting, in September 1970 decided to begin collecting arms, with Loku Athula placed in charge of the armed section and directed to collect 100,000 bombs. At the next PB meeting, held at year-end, Loku Athula reported that 3,000 bombs were ready.

The hand bomb was the JVPs main weapon. But guns and ammunition were also being purchased and stolen and stored by the JVP, in one instance at the Talagalle Temple at Homagama, which was raided by the Police. Uniforms for JVP combatants were being produced secretly, mainly at Vidyodaya Campus; a blue shirt and trouser with pockets, a cartridge belt, boots and helmet. In addition, Viraj Fernando, an engineer who was sympathetic to the JVP, had at Wijeweera’s request went overseas in November 1970 to make contact with foreign rebel groups to procure weapons.

Wijeweera also gave instructions to Piyasiri to build under-ground storage facilities to hide their stock of weapons and explosives, but on 9 March an explosion at one of these hideouts, in Nelundeniya, killed five. This drew attention, nationally to the fact that the JVP was arming itself.

Then on the 16 came an explosion at Marrs Hall at the Peradeniya Campus, in a room occupied by Hewavitharne. When the Police arrived and searched the halls of residence, they also found a stock of detonators at Hilda Obeysekera Hall.

A faction, within the JVP, led by Castro Dharmasekera, wanted the movement to remain secret and prepare for guerrilla warfare. But the majority disagreed and Dharmasekera and his supporters were expelled. In response, on 6th March, calling themselves the Maoist Youth Front, they held a demonstration outside the US Embassy in Colombo during which a police officer was killed. Although the JVP denounced Dharmasekera, Wijeweera and hundreds of his supporters were arrested during March, the JVP claimed that 4,000 cadre were now behind bars.

Dharmasekera’s provocation and the bomb explosions led on March 16th to the government declaring a State of Emergency, dusk to dawn curfew and their warning of a JVP plot to take state power. In response, the Army deployed two platoons of the 1st Battalion, Ceylon Light Infantry (1CLI) to the Kegalle District, which would soon become the centre of fierce fighting. This was followed by a further two platoons being sent to Kandy.

(To be continued tomorrow)

Features

International Women’s Day spurs re-visit of unresolved issues

‘Bread and Peace’. This was a stirring demand taken up by Russia’s working women, we are told, in 1917; the year the world’s first proletarian revolution shook Russia and ushered in historic changes to the international political order. The demand continues to be profoundly important for the world to date.

‘Bread and Peace’. This was a stirring demand taken up by Russia’s working women, we are told, in 1917; the year the world’s first proletarian revolution shook Russia and ushered in historic changes to the international political order. The demand continues to be profoundly important for the world to date.

International Women’s Day (IWD) is continuing to be celebrated the world over, come March, but in Sri Lanka very little progress has been achieved over the years by way of women’s empowerment, despite Sri Lanka being a signatory to the UN Convention on the Elimination of all Forms of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW) and other pieces of global and local legislation that promise a better lot for women.

The lingering problems in this connection were disturbingly underscored recently by the rape-assault on a female doctor within her consultation chamber at a prominent hospital in Sri Lanka’s North Central Province; to cite just one recent instance of women’s unresolved vulnerability and powerlessness.

The Bandaranaike Centre for International Studies, Colombo (BCIS) came to the forefront in taking up the above and other questions of relevance to women at a forum conducted at its auditorium on March 7th, in view of IWD. The program was organized by the library team at the BCIS, under the guidance of the BCIS Executive Director Priyanthi Fernando.

It was heartening to note that the event was widely attended by schoolchildren on the invitation of the BCIS, besides members of the public, considering that the awareness among the young needs to be consistently heightened and broadened on the principal issue of gender justice. Hopefully, going forward, the young would champion the cause of women’s rights having gained by the insights which have been surfaced by forums such as that conducted by the BCIS.

The panelists at the BCIS forum comprised Kumudini Samuel of the Women and Media Collective, a local organization which is in the forefront of taking up women’s issues, and Raaya Gomez, an Attorney-at-Law, engaged in women’s rights advocacy. Together they gave the audience much to think about on what needs to be done in the field of gender justice and linked questions.

The currently raging wars and conflicts worldwide ought to underscore as never before, the yet to be substantively addressed vulnerability of women and children and the absolute need for their consistent empowerment. It is plain to see that in the Gaza, for example, it is women and children who are put through the most horrendous suffering.

Yet, women are the sole care-givers and veritable bread winners of their families in particularly times of turmoil. Their suffering and labour go unappreciated and unquantified and this has been so right through history. Conventional economics makes no mention of the contribution of women towards a country’s GDP through their unrecorded labour and, among other things, this glaring wrong needs to be righted.

While pointing to the need for ‘Bread and Peace’ and their continuing relevance, Kumudini Samuel made an elaborate presentation on the women’s struggle for justice and equality in Sri Lanka over the decades. Besides being the first country to endow women with the right to vote in South Asia, Sri Lanka has been in the forefront of the struggle for the achievement of women’s rights in the world. Solid proof of this was given by Ms. Samuel via her presentation.

Schoolchildren at the knowledge-sharing session.

The presenter did right by pointing to the seventies and eighties decades in Sri Lanka as being particularly notable from the viewpoint of women’s advocacy for justice. For those were decades when the country’s economy was unprecedentedly opened or liberalized, thus opening the floodgates to women’s increasing exploitation and disempowerment by the ‘captains of business’ in the Free Trade Zones and other locations where labour rights tend to be neglected.

Besides, those decades witnessed the explosive emergence of the North-East war and the JVP’s 1987-’89 uprising, for example, which led to power abuse by the state and atrocities by militant organizations, requiring women’s organizations to take up the cause of ethnic peace and connected questions, such as vast scale killings and disappearances.

However, the presenter was clear on the point that currently Sri Lanka is lagging behind badly on the matter of women’s empowerment. For example, women’s representation currently in local councils, provincial councils and parliament is appallingly negligible. In the case of parliament, in 2024 women’s representation was just 9.8 %. Besides, one in four local women have experienced sexual and physical violence since the age of fifteen. All such issues and more are proof of women’s enduring powerlessness.

Raaya Gomez, among other things, dealt at some length on how Sri Lanka is at present interacting with and responding to international bodies, such as CEDAW, that are charged with monitoring the country’s adherence to international conventions laying out the state’s obligations and duties towards women.

This year, we were told, the Sri Lankan government submitted 11 reports to CEDAW in Geneva on issues raised by the latter with the state. Prominent among these issues are continuing language-related difficulties faced by minority group Lankan women. Also coming to the fore is the matter of online harassment of women, now on the ascendant, and the growing need for state intervention to rectify these ills.

It was pointed out by the presenter that overall what needs to be fulfilled by Sri Lanka is the implementation of measures that contribute towards the substantive equality of women. In other words, social conditions that lead to the vulnerability and disempowerment of women need to be effectively managed.

Moreover, it was pointed out by Gomez that civil society in Sri Lanka comes by the opportunity to intervene for women’s empowerment very substantively when issues relating to the Lankan state’s obligations under CEDAW are taken up in Geneva, usually in February.

Accordingly, some Lankan civil society organizations were present at this year’s CEDAW sessions and they presented to the body 11 ‘shadow reports’ in response to those which were submitted by the state. In their documents these civil society groups highlighted outstanding issues relating to women and pointed out as to how the Lankan state could improve its track record on this score. All in all, civil society responses amount to putting the record straight to the international community on how successful or unsuccessful the state is in adhering to its commitments under CEDAW.

Thus, the BCIS forum helped considerably in throwing much needed light on the situation of Lankan women. Evidently, the state is yet to accelerate the women’s empowerment process. Governments of Sri Lanka and their wider publics should ideally come to the realization that empowered women are really an asset to the country; they contribute immeasurably towards national growth by availing of their rights and by adding to wealth creation as empowered, equal citizens.

Features

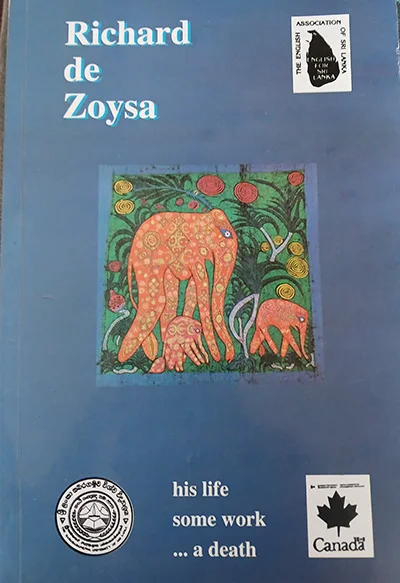

Richard de Zoysa at 67

by Prof. Rajiva Wijesinha

Today would have been Richard de Zoysa’s 67th birthday. That almost seems a contradiction in terms, for one could not, in those distant days of his exuberant youth, have thought of him as ever getting old. His death, when he was not quite 32, has fixed him forever, in the minds of those who knew and loved him, as exuding youthful energy.

It was 35 years ago that he was abducted and killed, and I fear his memory had begun to fade in the public mind. So we have to be thankful to Asoka Handagama and Swarna Mallawarachchi for bringing him to life again through the film about his mother. This was I think more because of Swarna, for I still recall her coming to see me way back in 2014 – August 28th it was, for my father was dying, though he was still mindful enough to ask me how my actress was after I had left him that afternoon to speak to her downstairs – to talk about her plans for a film about Manorani.

His friends have in general criticised the film, and I too wonder as to why she and the Director did not talk to more of his friends before they embarked on the enterprise. But perhaps recreating actual situations was not their purpose, or rather was not his, and that is understandable when one has a particular vision of one’s subject matter.

After listening to and reading the responses of his friends, I am not too keen to see the film, though I suspect I will do so at some stage. Certainly, I can understand the anger at what is seen as the portrayal of a drunkard, for this Manorani never to my knowledge was. But I think it’s absurd to claim there was never alcohol in the house, for there was, and Manorani did join in with us to have a drink, though she never drank to excess. Richard and I did, I fear, though not at his house, more at mine or at his regular haunt, the Art Centre Club.

I am sorry too that the ending of the film suggests that the murder was the responsibility of just its perpetrators, for there is no doubt that it was planned higher up. I myself have always thought it was Ranjan Wijeratne, who was primarily responsible, though I have no doubt that Premadasa also had been told – indeed Manorani told me that he had turned on Ranjan and asked why he had not been told who exactly Richard was.

But all that is hearsay, and it is not likely that we shall ever be able to find out exactly what happened. And otherwise it seems to me from what I have read, and in particular from one still I have seen (reproduced here), illustrating the bond between Richard and his mother, the film captures two vital factors, the extraordinary closeness of mother and son, and the overwhelming grief that Manorani felt over his death.

Despite this she fought for justice, and she also made it clear that she fought for justice not only for her son, but for all those whose loved ones had suffered in the reign of terror unleashed by JR’s government, which continued in Premadasa’s first fifteen months.

I have been surprised, when I was interviewed by journalists, in print and the electronic media, that none of them remembered Ananda Sunil, who had been taken away by policemen eight years earlier, when JR issued orders that his destructive referendum had to be won at all costs. Manorani told me she had met Ananda Sunil’s widow, who had complained, but had then gone silent, because it seemed the lives of her children had been threatened.

Manorani told me that she was comparatively lucky. She had seen her son’s body, which brought some closure, which the other women had not obtained. She had no other children, and she cared nothing for any threats against her own life for, as she said repeatedly, her life had lost its meaning with Zoysa’s death and she had no desire to live on.

I am thankful then that the film was made, and I hope it serves to renew Richard’s memory, and Manorani’s, and to draw attention to his extraordinary life, and hers both before and after his death. And I cannot be critical about the fact that so much about his life was left out, for a film about his mother’s response to his death could not go back to the past.

But it surprised me that the journalists did not know about his own past, his genius as an actor, his skill as a writer. All of them interviewed me for ages, for they were fascinated at what he had achieved in other spheres in his short life. Even though not much of this appeared in what they published or showed, I hope enough emerged for those interested in Richard to find out more about his life, and to read some of his poetry.

A few months after he died – I had been away and came back only six months later – I published a collection of his poetry, and then a few years later, having found more, republished them with two essays, one about our friendship, one about the political background to his death. And the last issue of the New Lankan Review, which he and I had begun together in 1983 in the tutory we had set up after we were both sacked from S. Thomas’, was dedicated to him. It included a striking poem by Jean Arasanayagam who captured movingly the contrast between his genius and the dull viciousness of his killers.

After those initial memorials to his life and his impact, I started working on a novel based on our friendship. I worked on this when I had a stint at the Rockefeller Centre in Bellagio in 1999, but I was not satisfied, and I worked on it for a few years more, before finally publishing the book in 2005. It was called The Limits of Love and formed the last book in my Terrorist Trilogy, the first book of which, Acts of Faith, had been written with his support, after the July 1983 riots. That was translated into Italian, as Atti di Fedi, and came out in 2006 in Milan.

The Limits of Love

did not receive much publicity, and soon afterwards I was asked to head the Peace Secretariat, and after that I wrote no more fiction. But when Godage & Bros had published several of my non-fiction works in the period after I was excluded from public life, I asked them to republish Acts of Faith, which they did, and that still remains in print. They also republished in 2020 Servants, my novel that won the Gratiaen Prize for 1995.

I thought then that it would be a good idea to republish The Limits of Love, and was delighted that Neptune agreed to do this, after the success of my latest political history, Ranil Wickremesinghe and the emasculation of the United National Party. I thought initially of bringing the book out on the anniversary of Richard’s death, but I had lost my soft copy and reproducing the text took some time. And today being Poya I could not launch the book on his birthday.

It will be launched on March 31st, when Channa Daswatte will be free to speak, for I recalled that 20 years ago my aunt Ena told me that he had admired the book. I think he understood it, which may not have been the case with some of Richard’s friends and relations, for this too is fiction, and the Richard’s character shares traits of others, including myself. The narrator, the Rajiv’s character, I should add is not myself, though there are similarities. He is developed from a character who appeared in both Acts of Faith and Days of Despair, though under another name in those books. Rajiv in the latter is an Indian Prime Minister, though that novel, written after the Indo-Lanka Accord, is too emotional to be easily read.

Manorani hardly figures in The Limits of Love. A Ranjan Wijesinghe does, and also a Ronnie Gooneratne, but of more interest doubtless will be Ranil and Anil, two rival Ministers under President Dicky, both of whom die towards the end of the book. Neither, I should add, bears the slightest resemblance to Ranil Wickremesinghe. His acolytes may try to trace elements of him in one or other of the characters, for I remember being told that Lalith Athulathmudali’s reaction to Acts of Faith was indignation that he had not appeared in it.

Fiction has, I hope, the capacity to bring history to life, and the book should be read as fiction. Doubtless there will be criticism of the characterisation, and of course efforts to relate this to real people, but I hope this will not detract from the spirit of the story, and the depiction of the subtlety of political motives as well as relationships.

The novel is intended to heighten understanding of a strange period in our history, when society was much less fragmented than it is today, when links between people were based on blood as much as on shared interests. But I hope that in addition it will raise awareness of the character of the ebullient hero who was abducted and killed 35 years ago.

The film has roused interest in his life, though through a focus on his death. The novel will I hope heighten awareness of his brilliance and the range of his activity in all too short a life.

Features

SL Navy helping save kidneys

By Admiral Ravindra C Wijegunaratne

WV, RWP& Bar, RSP, VSV, USP,

NI (M) (Pakistan), ndc, psn, Bsc (Hons) (War Studies) (Karachi) MPhil (Madras)

Former Navy Commander and Former Chief of Defense Staff

Former Chairman, Trincomalee Petroleum Terminals Ltd

Former Managing Director Ceylon Petroleum Corporation

Former High Commissioner to Pakistan

Navy’s efforts to eradicate Chronic Kidney Disease (CKD) from North Central and North Western Provinces:

• Navy’s homegrown technology provides more than Ten million litres of clean drinking / cooking water to the public free of charge.

• Small project Navy started on 22nd December 2015 providing great results today.

• 1086 Reverse Osmosis (RO) Water purification plants installed to date – each plant producing 10,000 litres of clean drinking water – better quantity than bottled water.

• Project continued for 10 years under seven Navy Commanders highlights the importance of “INSTITUTIONALIZING” a worthy project.

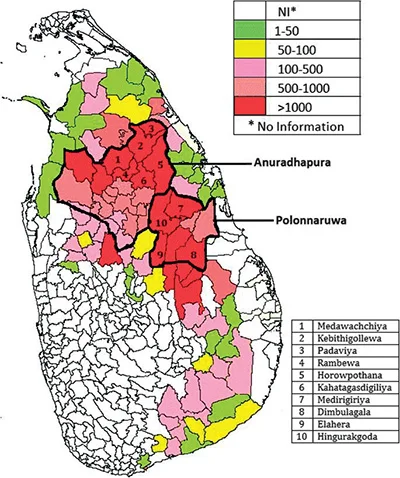

What you see on the map of Sri Lanka (Map 1) are RO water purification plants installed by SLN.SLN is famous for its improvisations and innovations in fighting LTTE terrorists out at sea. The Research and Development Institute of SLN started to use its knowledge and expertise for “Nation Building” when conflict was over in May 2009. On request of the Navy Commander, R and D unit of SLN, under able command of Commander (then) MCP Dissanayake, an Indian trained Marine Engineer, embarked on a programme to build a low- cost RO plant.

What you see on the map of Sri Lanka (Map 1) are RO water purification plants installed by SLN.SLN is famous for its improvisations and innovations in fighting LTTE terrorists out at sea. The Research and Development Institute of SLN started to use its knowledge and expertise for “Nation Building” when conflict was over in May 2009. On request of the Navy Commander, R and D unit of SLN, under able command of Commander (then) MCP Dissanayake, an Indian trained Marine Engineer, embarked on a programme to build a low- cost RO plant.

The Chronic Kidney Disease was spreading in North Central Province like a “wildfire “in 2015, mainly due to consumption of contaminated water. To curb the situation, providing clean drinking and cooking water to the public was the need of the hour.

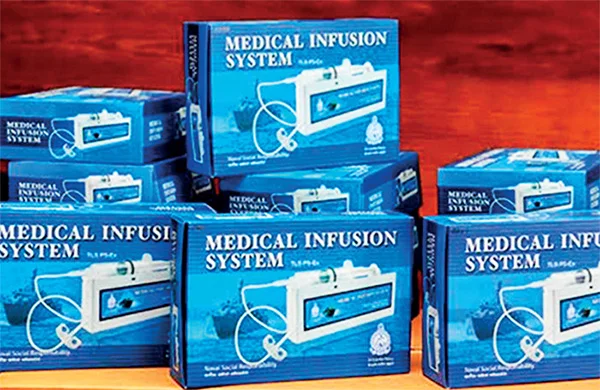

The Navy had a non-public fund known as “Naval Social Responsibility Fund “(NSR) started by former Navy Commander Admiral DWAS Dissanayake in 2010, to which all officers and sailors contributed thirty rupees (Rs 30) each month. This money was used to manufacture another project- manufacturing medicine infusion pumps for Thalassemia patients. Thalassemia Medicine Infusion pumps manufactured by SLN R and D Unit. With an appropriately 50,000 strong Navy, this fund used to gain approximately Rupees 1.5 million each month- sufficient funds to start RO water purification plant project.

Studies on the spreading of CKD, it was very clear of danger to the people of North central and North Western provinces, especially among farmers, in this rice producing province. The detailed studies on this deadly disease by a team led by Medical experts produced the above map (see Map 2) indicating clear and present danger. Humble farmers in “the Rice Bowl” of Sri Lanka become victims of CDK and suffer for years with frequent Dialysis Treatments at hospitals and becoming very weak and unable to work in their fields.

- Map 1

- Map 2

The Navy took ten years to complete the project, under seven Navy Commanders, namely Admiral Ravi Wijegunaratne, Admiral Travis Sinniah, Admiral Sirimevan Ranasinghe, Admiral Piyal De Silva, Admiral Nishantha Ulugethenna, Admiral Priyantha Perera, present Navy Commander Kanchana Banagoda. Total cost of the project was approximately Rs. 1.260 million. Main contributors to the project were the Presidential Task Force to Eradicate CDK (under the then President Mithripala Sirisena), Naval Social Responsibility Fund, MTV Gammedda, individual local and foreign donors and various organisations. Their contributions are for a very worthy cause to save the lives of innocent people.

The Navy’s untiring effort showed the World what they are capable of. The Navy is a silent force. What they do out at sea has seen only a few. This great effort by the Navy was also noticed by few but appreciated by humble people who are benefited every day to be away from deadly CKD. The Reverse Osmosis process required power. Each plant consumes approximately Rs 11,500 worth power from the main grid monthly. This amount brought down to an affordable Rs 250 per month electricity bill by fixing solar panels to RO plant building roofs. Another project to fix medical RO plants to hospitals having Dialysis machines. SLN produced fifty medical RO plants and distributed them among hospitals with Dialysis Machines. Cost for each unit was Rs 1.5 million, where an imported plant would have cost 13 million rupees each. Commodore (E) MCP Dissanayake won the prize for the best research paper in KDU international Research Conference 2021 for his research paper to enhance RO plant recovery from 50% to 75%. He will start this modification to RO plants soon making them more efficient. Clean drinking water is precious for mankind.

Thalassemia Medicine Infusion pumps manufactured by SLN R and D Unit

The Navy has realised it very well. In our history, King Dutugemunu (regained from 161 BC to 137 BC), united the country after 40 years and developed agriculture and Buddhism. But King Dutugemunu was never considered a god or deified. However, King Mahasen (277 to 304 AD) who built more than 16 major tanks was considered a god after building the Minneriya tank.

The people of the North Central Province are grateful to the Navy for providing them with clean drinking and cooking water free of charge daily. That gratitude is for saving them and their children from deadly CKD.

Well done Our Navy! Bravo Zulu!

-

News5 days ago

News5 days agoPrivate tuition, etc., for O/L students suspended until the end of exam

-

Features6 days ago

Features6 days agoShyam Selvadurai and his exploration of Yasodhara’s story

-

Editorial4 days ago

Editorial4 days agoRanil roasted in London

-

Latest News5 days ago

Latest News5 days agoS. Thomas’ beat Royal by five wickets in the 146th Battle of the Blues

-

News5 days ago

News5 days agoTeachers’ union calls for action against late-night WhatsApp homework

-

Editorial6 days ago

Editorial6 days agoHeroes and villains

-

Features4 days ago

Features4 days agoThe JVP insurrection of 1971 as I saw it as GA Ampara

-

Editorial5 days ago

Editorial5 days agoPolice looking for their own head