Features

Oranee Jansz

by Rajiva Wijesinha

Oranee Jansz died last month after a brave battle with cancer, one day after her 77th birthday. I knew her for just less than half her life, having first met her when I joined the University of Sri Jayewardenepura in 1992.

I had moved there mainly to look after the English courses at Affiliated University Colleges, the brainchild of Arjuna Aluwihare. But of course USJP wanted to make greater use of me, both to restructure its English courses and build up a Department, and also to revitalize teaching of English to all students through the English Language Teaching Unit.

This latter request did not go down well with the host of long serving ladies who ran the ELTU at the time, and amongst the most opposed to the intrusion of an outsider was Oranee. But fortunately, before I took any steps, I engaged in a thorough survey of the customers as it were of the ELTU, the heads of the different Faculties and Departments whose students were supposed to learn English through the ELTU.

I found almost total despair as to what they saw as the incapacity to enthuse or teach well of the different ladies, but they all thought very highly of Oranee and asked me to allocate her to their students. I realized from that that she was an exceptional person and I treated her with great respect, to which in time she responded positively. I believe we bonded when we walked up one day from the shed which housed the ELTU to the main gate of the university, and she asked me whether I believed the assurances her colleagues had given me that their programme was going well. I think she was relieved when I told her I knew there were problems.

Prof Palihawadana, a thorough gentleman as that other great gentleman J B Dissanayake described him, was acting as Vice-Chancellor at the time given the kerfuffle about the appointment of the university Librarian, Mr Dorakumbura, as Vice-Chancellor. Palihawadana was a shrewd judge of character and ability and had wanted to make Oranee the ELTU head, since the lady who had been there had resigned when told that I would be asked to take charge of their programmes. But Oranee’s colleagues, who were I think nervous of her, protested, and the former head took over again.

Instead Oranee was asked to take charge of English for the medical faculty USJP had just started. This was a salutary measure for she did a great job, using the participatory techniques she had developed, and her students blossomed. In the strange world of Sri Lankan medicine, where established universities roundly condemn the new ones and claim standards are being lowered, with the new universities that achieve respectability then joining the old brigade to condemn newer ones, USJP has the distinction of being the university that soonest gained enough respect to join the charmed circle. And while this was obviously due to the excellence of its teaching staff, I believe too that the self confidence Oranee developed, along with excellent communicative confidence in English, contributed to the speed with which USJP doctors achieved parity with their peers.

Oranee selected her own team for the medical faculty, and made short shrift of one of the nastier of her peers who fell like a vulture on the Tamils we recruited after I was put in charge of English. Even Parvathi Nagasunderam, whom I had enticed from the NIE, was driven to tears by the viciousness, claiming that USJP had been free of Tamils earlier and there was no room there for terrorists. But she had been recruited to the Languages Department and decided that she would have nothing more to do with them. This was their loss at the time, though soon enough the younger staff there looked on her as mentor and inspiration, as did the products of the English Department she presided over for many years.

Less confident was a Tamil gentleman who had in fact settled in Colombo as a refugee from Tiger violence, totally unprepared for the onslaught of the Amazons. Oranee promptly took him under her wing, and he became a loved teacher for the Medical Faculty.

That was Oranee, a woman of infinite courage and kindness, and a fantastic and inspiring teacher. She developed her own course for the Medical Faculty but deigned to make use of some of the materials I had prepared, which fortunately the other ladies teaching other students did not resist, not least because I took on the book for the AUCs that the ELTU head had prepared. This book, ‘People’ was actually quite good and, though I had to do some editing, this was much less than was needed for the second book. As to that I was delighted when, after I had revised it thoroughly, Prof Chitra Wickramasuriya of Colombo who had been Consultant to the AUC programmes before I took over remarked enthusiastically that ‘Objects’ had been transformed.

My own productions were a set of Student Workbooks which I later divided into two texts, ‘A Handbook of English Grammar’ and a reader called ‘Read, Think and Discuss’. This latter was in collaboration with Oranee for by then she and I were working together as Coordinators of the pre-University General English Language Teaching programme, the GELT which we rechristened a Training programme.

I had got involved because, on coming back to Sri Lanka in 1993 from my stay at the Rockefeller Centre in Bellagio, I met Prof A J Gunawardena on the plane and he said that they had not been able to find anyone satisfactory to take over the GELT. He knew I was acquainted with the programme, for while at the British Council I had been commissioned by the Canadians to produce readers for the course. A J suggested I call Arjuna Aluwihare and offer my services.

I did so, for it fitted in well with the AUC work, but Arjuna told me he had asked Oranee to take it over. I suggested that I could work with her, which pleased him for I think he had been wary about what the traditionalists in the ELTU would have said about Oranee, whose original degree had been in Chemistry, though she had of course qualified since in ELT through the Colombo University Master’s programme. This was a professional course unlike the one year apology for a course that Kelaniya offered at the time (since, I believe, upgraded to a reasonable one).

Oranee was not I think pleased at my involvement for she had looked forward to doing her own thing, but she soon found that I had no intention of restricting her. I was delighted at the many ideas she had for developing initiative and thinking skills, well aware then as others in her field were not of the importance of what are now described as Soft Skills. She was a great believer in group work, in setting exercises to get students to develop and defend their own ideas, and then setting guidelines for developing a productive consensus.

We got on superbly in the little office allocated to us at the UGC, along with the staff who had started the programme way back in the late eighties, Mr Saparamadu, Lilani Samaranayake, the indefatigable typist Padma, and the stolid office aide Joseph. Oranee kindly took charge of the office work, including the checking and signing of innumerable vouchers, while I travelled to monitor the centres, making it to almost all of them including Mannar Island and Tirukkovil, closing those which had few students and lazy teachers, encouraging the many who did excellent work.

I tried to get Oranee to visit the centres, but she was a good family woman and did not like to leave her husband and children. But she was wonderful at the training sessions for staff we held regularly in the auditorium, trying to ensure that traditional talk was abandoned and group work with unobtrusive but clear guidance was done. And Oranee also developed a system of getting the centres to Colombo, or rather those who came to the finals of the competition we established for dramatization of the projects we insisted all students engage in. These proved wildly successful, and the enthusiasm of the students, to look into a local problem and propound solutions for problems, was a joy to see.

When we started work Oranee was not enthusiastic about my effort to ensure accuracy, for she was then in thrall to the theories of a man called Krashen who pushed fluency and claimed insistence on accuracy inhibited that. But before long she granted that errors would get entrenched unless corrected, and became even more enthusiastic than I was about accuracy. She became a great proponent of the Grammar Handbook, while I bowed to her wonderful imagination and gave her free rein to introduce innovative exercises in the companion reader.

These were much loved by students but of course no other university wanted to use them, since they all made much of what they termed the production of materials for which of course they were paid (neither Oranee nor I took any money for what we produced). Later, when I was moving away from the university system, and realized that no one else would ensure the books were kept in print, I accepted the offer of Cambridge University Press in India to publish the two texts under their Foundation Books imprint.

Oranee was pleased that I attributed sole authorship of ‘Explorations’, as CUP entitled ‘Read, Think and Discuss’, to her, and delighted that she received royalties for the book, which had not of course happened in Sri Lanka. Indeed CUP had the books prescribed by some Indian universities, so we did well out of them, though in Sri Lanka endemic jealousy makes it impossible for students at other universities to benefit thus.

Indeed this came home to me when a member of the current UGC asked me about the GELT materials we had used, since he had been put in charge of reviving the GELT course and thought there was no need to reinvent the wheel. I sent him details, but since then I gather that the traditionalists have stepped in, and I suspect the new effort at a GELT will be as disastrous as the GELT became at the turn of the century when the UGC decided to decentralize it. Within a couple of years of that decision the UGC closed the programme on the grounds that very few students attended, which was indeed the case in urban areas run by the old universities but of course by then there was little concern about the rural students who had been the main beneficiaries. Incidentally the bonding we had developed had stood the students in good stead during the rag but that confidence was no more after GELT was abolished.

Oranee by then had enough to do for she had finally been appointed to head the ELTU at USJP. Meanwhile I had used her, as well as Paru, for the training I embarked on when I took on responsibility for the reintroduction of English medium in government schools at the end of 2001. Sadly Ranil Wickremesinghe forbade the Minister renewing my contract to coordinate this in the middle of 2002, and the programme began to collapse, as indeed Ranil’s brother told me in urging me to persuade the Prime Minister to take remedial action (which did not happen though I am not sure whether his animosity to English medium or to me was the greater reason for this stubbornness).

Fortunately Chandrika revived the programme, and by then Oranee was retired from USJP so I could get her to work at the Ministry, where she headed the lovely team I set up in 2004 and 2005. Once again I was fascinated by how much she inspired the staff I had taken on from Sabaragamuwa.

I saw less of Oranee later, after I entered the world of public affairs, but we kept in touch and when I heard she had cancer I made it a point to see her regularly. That had to cease when COVID struck, but I kept in touch on the telephone, and resumed my visits over the last couple of months. And whereas towards the end of last year she seemed to be weakening, she was much more feisty in the last few months, and was a great pleasure to talk to. As usual she did not mince her words and, having been enthusiastic last year about GELT being revived, she too thought this year that the initiative had fallen prey to the incoherence that bedevils our system, and lots of people will make lots of money reinventing wheels and producing second rate materials.

But we talked about much more, mutual friends, students whom she had nurtured, politics, fellow academics about whom she had entertaining stories. And her zest for life was exemplified too when she insisted on seeing my dog, who was generally with me for I usually saw her when travelling to my cottage. His name is Toby, but she insisted that he had to have a surname that matched his distinguished appearance, and designated him Toby Parker Bowles.

That too, that zany zest for life, along with a deep affection for all those weaker than herself, a forceful commitment to social justice, an indefatigable appetite for action, and a vivid imagination, contribute to the memory of a wonderful colleague and a dear friend.

Features

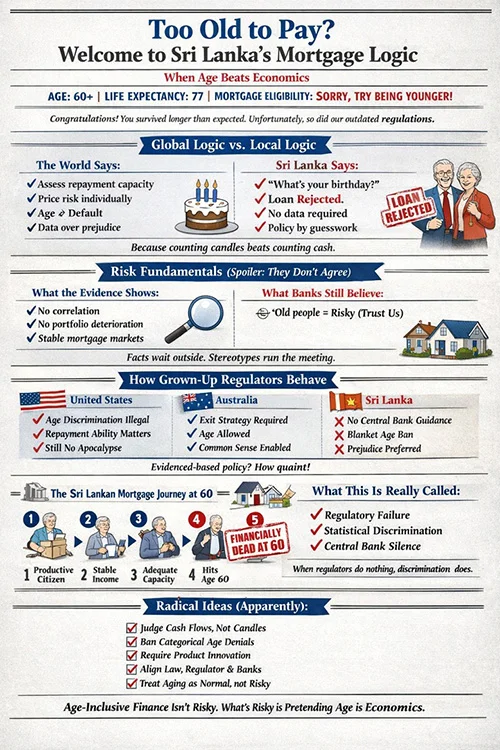

The world welcomes senior home buyers while Sri Lanka shuts the door at 60

Imagine you are 58 years old, financially stable with a decent pension plan, and finally ready to build your dream home in the suburbs of Colombo. You walk into a bank, application in hand, only to be told: “Sorry, your repayment period would extend past 60. We can’t help you”. In Sri Lanka, this scenario plays out daily, leaving thousands of mature, creditworthy citizens locked out of homeownership. But, step outside our shores, you’ll find a drastically different story.

Imagine you are 58 years old, financially stable with a decent pension plan, and finally ready to build your dream home in the suburbs of Colombo. You walk into a bank, application in hand, only to be told: “Sorry, your repayment period would extend past 60. We can’t help you”. In Sri Lanka, this scenario plays out daily, leaving thousands of mature, creditworthy citizens locked out of homeownership. But, step outside our shores, you’ll find a drastically different story.

From the gleaming towers of Singapore to the countryside cottages of the United Kingdom, older borrowers aren’t just tolerated; they’re actively courted by lenders who understand that age doesn’t determine creditworthiness. While Sri Lankan banks remain trapped in outdated policies that effectively discriminate against anyone over 50, the rest of the world has moved on, creating flexible, dignified pathways for seniors to access home loans.

Role of the Central Bank and the Government

The Central Bank of Sri Lanka has failed in its fiduciary duty by not directing financial institutions to refrain from arbitrarily denying home loans, solely on the basis of age. The Ministry of Finance, therefore, the government, is equally responsible for this failure.

This regulatory vacuum enables systematic discrimination against creditworthy older citizens, contradicting modern banking principles and harming an ageing population desperately needing progressive, not punitive, financial policies.

The Global Picture: Where Age is Just a Number

Many advanced economies, such as the United States and Canada, etc., there is no maximum age limit, whatsoever, for obtaining a 30-year mortgage. The Equal Credit Opportunity Act explicitly prohibits age discrimination, meaning an 80-year-old American can walk into a bank and apply for the same three-decade loan term as a 30-year-old, provided they meet income and credit requirements. Lenders evaluate based on current financial stability, not birth certificates. A 65-year-old Canadian with a solid pension can secure a mortgage extending well into their seventies, with the understanding that income, not age, determines repayment capacity.

Australia sets the typical retirement age benchmark at 65-75, and borrowers, over 65, can still obtain mortgages by demonstrating an exit strategy; a credible plan for repayment that might include downsizing, superannuation funds, or ongoing retirement income. The system acknowledges that life doesn’t end at 60, and neither should financial opportunity.

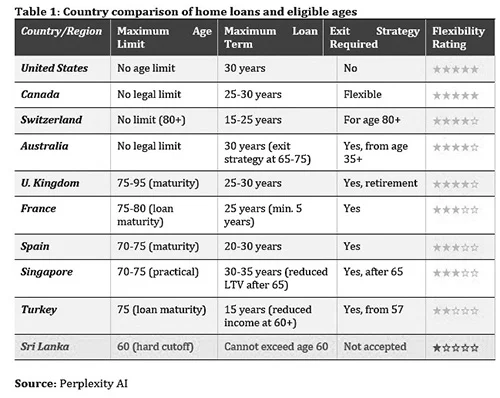

Global Home Loan Conditions:

A Comparative Analysis

The following table ranks countries from most to least affordable for older home loan applicants, based on maximum age limits, flexibility of terms, and accessibility of financing (Table 1).

What Makes These Systems Work?

The countries at the top of our affordability ranking share several key characteristics. First, they recognise that retirement doesn’t mean financial incapacity. Banks in these countries evaluate total financial health, not just employment status.

Second, they embrace the concept of exit strategies, in Australia, for instance, acceptable exit strategies include downsizing property, selling investment assets, or using superannuation (retirement) funds. These strategies are actually considered and evaluated, not dismissed out of hand. Australian lenders assess whether someone’s superannuation balance is sufficient to clear the debt, or if their investment property provides adequate cash flow. It’s a conversation, not a closed door.

Third, many of these countries offer specialised products for older borrowers. The UK, for example, has retirement interest-only mortgages where borrowers pay only interest during their lifetime, with the principal cleared when the property is eventually sold.

Australia provides reverse mortgages for those aged 60 and above. Under this arrangement, the bank pays the homeowner, rather than the homeowner paying the bank, using the house as security. The full outstanding balance is then recovered when the property is eventually sold.

These may not be perfect solutions, but they represent creative thinking about how to serve an ageing population’s housing needs.

The Hidden Cost of Age Discrimination

Sri Lanka’s rigid age-60 cutoff carries consequences that ripple far beyond individual borrowers. In a nation where life expectancy now exceeds 77 years, we’re telling people they are 17 years of ‘too old’ to be trusted ahead of them. This isn’t just unfair; it’s economically counterproductive.

Consider the broader impact. Sri Lanka has one of Asia’s fastest-aging populations. By 2050, one in four Sri Lankans will be over 60. These aren’t economic liabilities; many are professionals with decades of experience, stable incomes, and substantial assets. A 58-year-old doctor with thriving practice and pension security poses less default risk than a 28-year-old in an uncertain job market, yet our banking system treats them as if the opposite were true.

Learning from Singapore: A Regional

Success Story

We don’t need to look to distant Western nations for alternatives. Singapore, our regional neighbour facing similar demographic challenges, has crafted a more balanced approach. While Singapore’s Monetary Authority hasn’t imposed a hard age limit, banks do apply careful scrutiny to loans extending past age 65.

A Singaporean borrower, over 65, can still obtain financing, but with reduced loan-to-value ratios. If you’re buying a property worth one million dollars and you’re under 65, you might borrow up to 75 percent. Over 65, that drops to 60 percent. It’s more conservative, certainly, but it preserves opportunity.

This approach acknowledges risk without eliminating possibility. It says to older borrowers: Yes, we’ll lend it to you, but we need you to have more equity in the game. Compare this to Sri Lanka’s approach, which effectively says: “We don’t care how much equity you have or how stable your income is, you’re too old”.

A Path Forward for Sri Lanka

The Central Bank of Sri Lanka could issue guidelines similar to Singapore’s loan-to-value adjustments. For borrowers whose loan terms extend past 65, reduce the maximum LTV from 90 percent to 70 or 75 percent.

The Central Bank of Sri Lanka could issue guidelines similar to Singapore’s loan-to-value adjustments. For borrowers whose loan terms extend past 65, reduce the maximum LTV from 90 percent to 70 or 75 percent.

This protects banks from excessive risk while allowing creditworthy older borrowers to access financing. It’s a middle ground that respects both prudent lending standards and individual dignity.

Additionally, Sri Lanka could develop specialised products for its ageing population. Retirement interest-only loans, similar to those in the UK, could serve retirees who have substantial home equity but limited monthly income. Reverse mortgages, properly regulated with strong consumer protections, could help elderly Sri Lankans tap into home equity without monthly payments.

Beyond Banking: A Cultural Shift

Ultimately, changing Sri Lanka’s approach to older borrowers requires more than policy adjustments; it demands a cultural reckoning with how we value our ageing citizens. The countries that lead in age-friendly lending, the United States, Canada, Australia, share a broader commitment to recognising that people can remain economically active and financially responsible well into their later years.

These nations have moved beyond viewing retirement as an endpoint and recognised it as a transition. A 65-year-old today might have 20 or more active years ahead, years in which they’ll continue working part-time, managing investments, drawing stable pensions, and yes, making mortgage payments. Our banking sector needs to catch up to this reality.

Conclusion: Time for Change

As our table demonstrates, Sri Lanka stands alone at the bottom of the global ranking for age-friendly home lending. We’re more restrictive than Turkey with its 15-year maximum terms, more inflexible than Singapore with its sliding loan-to-value scales, and incomparably more rigid than the United States, Canada, or Switzerland, where age barely factors into lending decisions at all.

This isn’t about being soft on risk or abandoning prudent lending standards. Countries with no age limits still assess income, evaluate debt-to-income ratios, and verify creditworthiness. They simply don’t use age as a crude proxy for financial competence. The initiative lies with the Ministry of Finance, which must direct the Central Bank accordingly.

For Sri Lanka’s 58-year-old aspiring homeowner, the current system isn’t just frustrating; it’s a form of systematic discrimination that would be illegal in most developed economies. As our population ages and life expectancy increases, maintaining this policy becomes increasingly untenable. The question isn’t whether Sri Lankan banks will change their approach to older borrowers, but when and how many dreams will be deferred or destroyed in the meantime.

The world has shown us better ways forward. It’s time Sri Lanka joined the 21st century in recognising that 60 isn’t the end of financial opportunity for many, it’s just the beginning.

(The writer, a senior Chartered Accountant and professional banker, is Professor at SLIIT, Malabe. The views and opinions expressed in this article are personal.)

Features

Securing public trust in public office: A Christian perspective – Part II

This is an adapted version of the Bishop Cyril Abeynaike Memorial Lecture delivered on 14 June 2025 at the invitation of the Cathedral Institute for Education and Formation, Colombo, Sri Lanka.

(Continued from yesterday)

The public are entitled to expect their public servants to be intrinsically committed to the truth. From a consequentialist perspective, to secure public trust, public office must be oriented towards justice. Public officers ought to lend their mind to responding to the injustices that they can address within their mandate. This is precisely what Lalith Ambanwela did. His job was to audit the accounts, which he did truthfully and thereby revealed injustices. If he had paused to worry about the risks involved or if he had wondered whether he could have rid the entire system of corruption, the obvious answer to that would have stopped him from taking any truthful action. Rather, he responded to the injustice that he saw, in a truthful manner, thereby improving the trust the public could have in his office.

Notwithstanding the Ambanwela example, one may still ask, in a place like Sri Lanka, what is the point in a single public official being truthful in a context where the problems are institutional, systemic, generational and entrenched – such as corruption or abuse of power? Many of us are familiar with the line of reasoning which suggests that there is no point in being truthful as a single individual, at any level of public service- there will be no impact except for trouble and stress; that one person cannot change systems; that one must wait for a more suitable time; that one must be strategic; that one must think of one’s children safety and future; and that one must be cautious and not attract trouble. Women, in particular, are told – do not be difficult or extreme, just let this go because you cannot change the world.

This is where we come back to the intrinsic justification for truthfulness and a Christian perspective helps us understand the need to cultivate such an intrinsic motivation. The commitment to truthfulness, the Christian faith suggests, is not subject to whether the consequences are palatable or not, as to whether you may be successful or not, but rather, regardless of those consequences. But to sustain such a commitment to truthfulness, I think we need a nurturing environment – a point which I do not have time to speak to today.

Before moving to the second attribute, which is rationality, I want to mention a few other points that I will not be dealing with today. We need to acknowledge that there can be different approaches to discovering the truth and there can be, at least in some instances, different truths. This is reflected in the fact that we have four Gospels that account for the life and ministry of Jesus, reminding us that pursuing the truth has its own in-built challenges. Furthermore, truth is inter-dependent with many other attributes, including trust and freedom.

·

1. Rationality

I now turn to rationality, the second attribute that I think is necessary for securing public trust in public office. In public law, which is the area of law that I specialise in, rationality is a core value and a foundational principle. In contrast, it is fair to say that religion is commonly understood as requiring a faith-based approach – often considered to be the anti-thesis of rationality. However, the creation account in the Bible suggests to us that we were created in the image of God and that at least one of the attributes of human nature is rationality. Furthermore, it has been argued that even Science, generally considered to be a discipline based on rationality and objectivity, is also ultimately based on assumptions and therefore on belief. A previous lecture in this lecture series, by Prof Priyan Dias, explored these ideas in detail.

In my study of public law and in my own experiences in exercising public power, I have observed, of myself and of others like me, that cultivating rationality and maintaining a commitment to it, is a challenge. The need for rationality arises when we are given discretion. Academics, for instance, are given discretion in grading student exams or when supervising doctoral students. Members of the judiciary exercise significant discretion in hearing cases. In Sri Lanka’s Constitutional Council, the members have discretion to approve or disapprove the nominations made by the President to constitutional high office including to the office of the Chief Justice and Inspector General of Police. As I mentioned earlier, where there is discretion, the law requires the person exercising that discretion to be rational.

How should public officials practice rationality? In my view, there are five aspects to practicing rationality in decision-making. First, public officials ought to be able to think objectively about each decision they are required to make. Second, to think objectively, we have to be able to identify the purpose for which discretionary power has been given to us. Third, where necessary, we ought to consult others and/or seek advice and fourth, we have to be able to resist any pressure that might be cast on us, to be biased. Fifth, we should have reasons for our decision and consider it our duty to state those reasons to the world at large.

Let me say a bit more about these five aspects. When, as public officials, we exercise discretionary power, we ought to cultivate the habit of separating the personal from the professional. In public law we say that we should adopt the perspective of a fair minded and reasonable observer. But we know that our own situations often shape even our very idea of objectivity. For example, if a decision-making body comprises only men, or if a public institution has been only headed by men or has very few women at decision-making levels, objectivity could very well lead to decision-making that does not take account of the different issues that women face. All this to say, that objectivity is not simply the absence of personal bias but a way of making decisions where a public official is committed to taking account of all relevant perspectives and thinking rationally about them. No easy task, but that, I think, is what is required of public officials who seek to secure public trust.

The second aspect to rationality is having an appreciation and commitment to the purpose for which discretion has been vested in us. To do so, as public officials, whether we like it or not, we need to have some appreciation for the legal or policy basis on which discretionary power has been vested in us. You may think that this makes the job easier for lawyers. Well, I can tell you that it has not been uncommon for me to be in decision-making situations where even lawyers do not know or have not done their homework to understand what the law requires of us. Recall here the second example I cited, that of Thulsi Madonsela, the former Public Protector of South Africa. She was very clear about the purpose of her office – to ensure accountability. The rationality of her reports on the excessive spending on the President’s house and the report on state capture, have withstood the test of time and spoken truth to power, rationally.

Permit me to make a further point here. The law itself can, and, sometimes is, unjust or unclear. In such contexts, what is the role of a public official? In Sri Lanka, only the Parliament can change laws. Those who hold public office and who derive power from a specific law can only implement it. But and this is very significant, almost always, public officials are required to interpret the law in order to understand its purpose, scope etc. For instance, in Sri Lanka, the law does not lay down the minimum qualifications for several key constitutional offices. The nomination of persons to these offices is through a process of convention, that is to say practice. In my view, this is far from desirable. However, while the law remains this way, the President has the discretion to nominate persons to these constitutional offices and the Constitutional Council is required to approve or disapprove such nominations. The lack of clarity in the relevant constitutional provisions casts a heavy duty on both the President and the Constitutional Council to ensure that they all exercise the discretion vested in them, for the purpose for which such discretion has been given. To do so, both the President and the Council ought to have an appreciation for each of these constitutional high offices, such as that of the Attorney-General or Auditor General and exercise their discretion rationally for the benefit of the people.

Consulting relevant parties and obtaining advice is the third aspect of rationality that I identified. It is not unusual for public officials to consult or obtain advice. Complex decisions are often best made with feedback from suitably qualified and experienced persons. who will share their independent opinion with you and where necessary, disagree with you. However, what I have observed in my work so far is the following. Public officials who seek advice, often select other public officials or experts who they like, or ones with whom they have a transactional relationship or ones who may not think differently from them. Correspondingly, the advice givers, often public officials themselves, seek to agree and please (or even appease) rather than give independent, subject based rational advice. This type of advice subverts the purpose of the law, bends it to political will and is disingenuous. I am sure, we can all think of examples from Sri Lanka where this has happened, sometimes even causing tragic loss of life or irreversible harm to human dignity.

Permit me to give you a personal example which is now etched in my mind. In November, 2023, the then President proposed to the Parliament that due to the non-approval of a nomination he had made to judicial office, that a Parliamentary Select Committee should be appointed to inquire into the Constitutional Council (The Sunday Times 26 November 2023). Feeling overwhelmed by the prospect of being hauled before a Parliamentary Select Committee while also recalling experiences of some public officials before such proceedings, the day after this announcement was made, I sat at my desk and typed out my letter of resignation (Daily Mirror 23 November 2023). I then rang up one of my lawyers to discuss this. I told him that I am resigning as I could not take what was to come. He responded very gently and made two points: 1) that I ought to not resign and need to see this through, whatever the process might entail and 2) that he and others will stand by me every step of the way. As you can imagine, that was not what I wanted to hear and it distressed me even more. Today, I recall that conversation with much humility and appreciation. That advice was certainly not what I wanted to hear that night but most certainly what I needed to hear.

The fourth aspect of rationality is resisting pressure which I will address later.

I will only speak briefly on the fifth aspect of rationality – that of having and stating reasons for decisions. In my view, if a public official is not able to provide reasons for a decision, it is a good indication of the need to rethink that decision. The external dimension of this aspect is one we all know. When a public official exercises public power, they are obliged to explain the reasons for their decisions. This is essential for securing the trust of the people and they owe it to us because they exercise public power, on our behalf. It goes without saying that public officials and the public should know the difference between rational reasons and reasons which are disingenuous – reasons which seek to hide rather than reveal.

So, to sum up on the points I made about rationality, I highlighted five features of this attribute, being objective in decision-making, being limited and guided by the purpose for which discretionary power has been given, consulting and/or seeking honest and expert-based advice, resisting any pressure to be biased and recording reasons for decisions. (To be continued)

by Dinesha Samararatne

Professor, Dept of Public & International Law, Faculty of Law, University of Colombo, Sri Lanka and independent member, Constitutional Council of Sri Lanka (January 2023 to January 2026)

Features

From disaster relief to system change

The impact of Cyclone Ditwah was asymmetric. The rains and floods affected the central hills more severely than other parts of the country. The rebuilding process is now proceeding likewise in an asymmetric manner in which the Malaiyaha Tamil community is being disadvantaged. Disasters may be triggered by nature, but their effects are shaped by politics, history and long-standing exclusions. The Malaiyaha Tamils who live and work on plantations entered this crisis already disadvantaged. Cyclone Ditwah has exposed the central problem that has been with this community for generations.

A fundamental principle of justice and fair play is to recognise that those who are situated differently need to be treated differently. Equal treatment may yield inequitable outcomes to those who are unequal. This is not a radical idea. It is a core principle of good governance, reflected in constitutional guarantees of equality and in international standards on non-discrimination and social justice. The government itself made this point very powerfully when it provided a subsidy of Rs 200 a day to plantation workers out of the government budget to do justice to workers who had been unable to get the increase they demanded from plantation companies for nearly ten years. The same logic applies with even greater force in the aftermath of Cyclone Ditwah.

A discussion last week hosted by the Centre for Policy Alternatives on relief and rebuilding after Cyclone Ditwah brought into sharp focus the major deprivation continually suffered by the Malaiyaha Tamils who are plantation workers. As descendants of indentured labourers brought from India by British colonial rulers over two centuries ago, plantation workers have been tied to plantations under dreadful conditions. Independence changed flags and constitutions, but it did not fundamentally change this relationship. The housing of plantation workers has not been significantly upgraded by either the government or plantation companies. Many families live in line rooms that were not designed for permanent habitation, let alone to withstand extreme weather events.

Unimplementable Promise

In the aftermath of the cyclone disaster, the government pledged to provide every family with relief measures, starting with Rs 25,000 to clean their houses and going up to Rs 5 million to rebuild them. Unfortunately, a large number of the affected Malaiyaha Tamil people have not received even the initial Rs 25,000. Malaiyaha Tamil plantation workers do not own the land on which they live or the houses they occupy. As a result, they are not eligible to receive the relief offered by the government to which other victims of the cyclone disaster are entitled. This is where a historical injustice turns into a present-day policy failure. What is presented as non-partisan governance can end up reproducing discrimination.

The problem extends beyond housing. Equal rules applied to unequal conditions yield unequal outcomes. Plantation workers cannot register their small businesses because the land on which they conduct their businesses is owned by plantation companies. As their businesses are not registered, they are not eligible for government compensation for loss of business. In addition, government communication largely takes place in the Sinhala language. Many families have no clear idea of the processes to be followed, the documents required or the timelines involved. Information asymmetry deepens powerlessness. It is in this context that Malaiyaha Tamil politicians express their feeling that what is happening is racism. The fact is that a community that contributes enormously to the national economy remains excluded from the benefits of citizenship.

What makes this exclusion particularly unjust is that it is entirely unnecessary. There is anything between 200,000-240,000 hectares available to plantation companies. If each Malaiyaha Tamil family is given ten perches, this would amount to approximately one and a half million perches for an estimated one hundred and fifty thousand families. This works out to about four thousand hectares only, or roughly two percent of available plantation land. By way of contrast, Sinhala villages that need to be relocated are promised twenty perches per family. So far, the Malaiyaha Tamils have been promised nothing.

Adequate Land

At the CPA discussion, it was pointed out that there is adequate land on plantations that can be allocated to the Malaiyaha Tamil community. In the recent past, plantation land has been allocated for different economic purposes, including tourism, renewable energy and other commercial ventures. Official assessments presented to Parliament have acknowledged that substantial areas of plantation land remain underutilised or unproductive, particularly in the tea sector where ageing bushes, labour shortages and declining profitability have constrained effective land use. The argument that there is no land is therefore unconvincing. The real issue is not availability but political will and policy clarity.

Granting land rights to plantation communities needs also to be done in a systematic manner, with proper planning and consultation, and with care taken to ensure that the economic viability of the plantation economy is not undermined. There is also a need to explain to the larger Sri Lankan community the special circumstances under which the Malaiyaha Tamils became one of the country’s poorest communities. But these are matters of design, not excuses for inaction. The plantation sector has already adapted to major changes in ownership, labour patterns and land use. A carefully structured programme of land allocation for housing would strengthen rather than weaken long term stability.

Out of one million Malaiyaha Tamils, it is estimated that only 100,000 to 150,000 of them currently work on plantations. This alone should challenge outdated assumptions that land rights for plantation communities would undermine the plantation economy. What has not changed is the legal and social framework that keeps workers landless and dependent. The destruction of housing is now so great that plantation companies are unlikely to rebuild. They claim to be losing money. In the past, they have largely sought to extract value from estates rather than invest in long term community development. This leaves the government with a clear responsibility. Disaster recovery cannot be outsourced to entities that disclaim responsibility when it becomes inconvenient in dealing with citizens of the country with the vote.

The NPP government was elected on a promise of system change. The principle of equal treatment demands that Malaiyaha Tamil plantation workers be vested with ownership of land for housing. Justice demands that this be done soon. In a context where many government programmes provide land to landless citizens across the country, providing land ownership to Malaiyaha Tamil families is good governance. Land ownership would allow plantation workers to register homes, businesses and cooperatives and would enable them to access credit, insurance and compensation which are rights of citizens guaranteed by the constitution. Most importantly, it would give them a stake that is not dependent on the goodwill of companies or the discretion of officials. The question now is whether the government will use this moment to rebuild houses and also a common citizenship that does not rupture again.

by Jehan Perera

-

Business2 days ago

Business2 days agoComBank, UnionPay launch SplendorPlus Card for travelers to China

-

Business3 days ago

Business3 days agoComBank advances ForwardTogether agenda with event on sustainable business transformation

-

Opinion6 days ago

Opinion6 days agoRemembering Cedric, who helped neutralise LTTE terrorism

-

Business6 days ago

Business6 days agoCORALL Conservation Trust Fund – a historic first for SL

-

Opinion3 days ago

Opinion3 days agoConference “Microfinance and Credit Regulatory Authority Bill: Neither Here, Nor There”

-

Opinion5 days ago

Opinion5 days agoA puppet show?

-

Opinion2 days ago

Opinion2 days agoLuck knocks at your door every day

-

Features5 days ago

Features5 days ago‘Building Blocks’ of early childhood education: Some reflections