Features

Ontario’s Bill 104: ‘Tamil Genocide Education or Miseducation Week?’

By Dharshan Weerasekera

In May 2021, the Legislative Assembly of Ontario adopted Bill 104. The stated purpose of the Bill is to, a) designate the week following May 18 each year as ‘Tamil Genocide Education Week’ and b) educate Ontarians about ‘Tamil Genocide and other genocides that have occurred in world history.’ The crucial question is, whether the charge of ‘Tamil genocide’ is true.

To the best of my knowledge, there has been very little substantive discussion of the above question in Sri Lankan or Canadian newspapers or academic journals in recent years and it is in public interest to begin such a discussion. Otherwise, there is a danger that the proposed ‘Tamil Genocide Education Week’ would turn out to be an exercise in mis-education of Canadians, most of whom are relatively unfamiliar with Sri Lanka.

In my view, there is absolutely no factual basis for anyone to claim that Tamils have been subjected to genocide in Sri Lanka. In this article, I shall briefly summarise the arguments made in a case filed in the Court of Appeal in September 2014, Polwatta Gallage Niroshan v. Inspector General of Police, Members of the Northern Provincial Council and others, CA/writ/332/2014. It is a public document. I was the Counsel in the case. The petitioner sought a writ of mandamus to compel the Attorney General to take action against members of the then Northern Provincial Council who had signed a letter (forwarded to the UN Human Rights High Commissioner) alleging genocide of Tamils in Sri Lanka.

Unfortunately, the Court declined to take up the case on technical grounds, namely, that the petitioner had failed to file a police complaint. The petitioner, a humble three-wheeler driver, did not have the financial wherewithal to pursue the matter further, but the case is very important in the present context because of two reasons: First, it shows that Sri Lankan citizens have rejected the allegation of Tamil genocide and even gone to the courts with regard to this matter.

Right of reply

Second, and more importantly, since the provincial legislature of a foreign country has asserted that Tamil genocide has happened, it is incumbent on the said legislature to provide a right of reply to all concerned Sri Lankans who reject the charge. Otherwise, one cannot expect the stated purpose of the Bill, education, to genuinely take place. In this regard, it is well to recall that natural justice, which includes the injunction “hear the other side” is an overriding principle (jus cogens) of international law.

Furthermore, one could argue that any funds allocated by the Ontario legislature, to advance the goals of the Bill, should be made available to members of Sri Lankan origin living in Ontario as well, who wish to tell their side of the story during the week in question. For all these reasons, the Sri Lankan case is important as a starting point for a substantive discussion of the charge of Tamil genocide. I give below the relevant portion:

“The 3rd – 35th Respondents, 28 of whom are members of the Northern Provincial Council and five are members of the Eastern Provincial Council, are signatories to a letter sent to the former United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights, Navinetham Pillay, titled, “Joint letter by members of the Northern Provincial Council and Eastern Provincial Council, 17 August 2014.” In the said letter the 3rd – 35th Respondents request the former UN Human Rights High Commissioner to acquaint her successor, as well as the investigating panel presently investigating Sri Lanka, with the matters contained in the letter.

Petitiner’s contention

The Petitioner contends that the said letter contains explicit statements capable of causing disharmony, ill-feeling and discord among the different ethnic groups of Sri Lanka, particularly the Sinhalese and the Tamils, that the 1st and 2nd Respondents have not taken any steps to investigate or prosecute the 3rd – 35th Respondents for the said statements under Section 120 of the Penal Code (raising discontent or disaffection or feelings of ill-will and hostility among the people) and therefore the Petitioner has a right to request the court for a writ of mandamus to compel action.

The letter makes three requests of the High Commissioner, the second of which is: “The Tamil people strongly believe that they have been, and continue to be, subjected to genocide in Sri Lanka. The Tamils were massacred in groups, their temples and churches were bombed, and their iconic Jaffna Public Library was burnt down in 1981 with its collection of largest and oldest priceless irreplaceable Tamil manuscripts. Systematic Sinhalese settlements and demographic changes with the intent to destroy the Tamil Nation, are taking place. We request that the OHCHR investigative them to look into the pattern of all the atrocities against the Tamil people, and to determine if Genocide has taken place.”

The Petitioner respectfully draws the attention of the court to two matters in the above passage:

i)

The assertion that Genocide has been practised against the Tamils in Sri Lanka.

ii)

That “Sinhalese settlements and demographic changes” are being carried out with the “intent to destroy the Tamil Nation.”

The Petitioner is of the view that, the above two assertions are demonstrably false, and, as a citizen of Sri Lanka, is personally offended and angered by them, and considers that thousands of other citizens of this country feel this way also.

The Petitioner further considers that, false accusations regarding highly sensitive issues made directly to the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights urging her to investigate the purported offenses constitute an attempt to “raise discontent or disaffection amongst the People of Sri Lanka, or to promote feelings of ill-will and hostility between different classes of such people” for the following reasons. The crime of genocide has a technical meaning in international law, and one can assess objectively whether or not that crime has been committed. The definition of genocide is set out in the Convention on the Prevention of Genocide (1948) and is as follows:

“[Article 2] In the present Convention, genocide means any of the following acts committed with the intent to destroy, in whole or in part, a national, ethnical, racial or religious group, as such:

a)

Killing members of the group;

b)

Causing serious bodily harm or mental harm to members of the group;

c)

Deliberately inflicting on the group conditions of life calculated to bring about its physical destruction in whole or in part.

d)

Imposing measures intended to prevent births within the group;

e)

Forcibly transferring children of the group to another group.”

From the above, it is clear that the crime of “Genocide” has two components: the intention to destroy, in whole or in part, a national, ethnical, racial or religious group, and also the committing of one or more of the acts enumerated under points a – e. It is possible to objectively assess whether, in a given set of circumstances, each of those components is present. Similarly, the accusation regarding settlements and the claim that the intent behind these settlements is to destroy the “Tamil Nation” can be objectively assessed.

The Petitioner asserts that, the Sinhalese people have not committed genocide against the Tamil people, or imposed settlements to destroy the Tamil People, or any “Tamil Nation” within this country, and that facts exist to prove these matters. In particular, the Petitioner wishes to draw the attention of the court to the following points: With respect to the accusation of genocide, the following facts are relevant:

Statistsics

Firstly, if the charge of ‘Genocide’ is with respect to the period from Independence to the start of the war, roughly 1948 – 1981, then statistics are available regarding key economic factors such as income, production assets in agriculture and manufacturing, employment, access to education, and access to health services. ((The most recent island-wide census was in 2012 which is after the war. But there is a census for 1981.) If discernible discrepancies exist between the statistics for the Sinhalese and the Tamils with regard to the above factors, a reasonable inference can be drawn that the Tamils have been systematically discriminated against, which would support the contention that the Tamils have been subjected to a genocidal campaign.

The Petitioner is of the considered view that a comparison of the aforementioned factors will show no discernible differences between the Sinhalese and the Tamils, and draws support for this contention from the assessment of Professor G.H. Peiris, one of Sri Lanka’s most respected scholars, who analyses the said factors in a chapter titled “Economic causes for ethnic conflict” in his book, Sri Lanka: Challenges for the new Millennium (2006). The said assessment is as follows:

“To generalize, the overall impression conveyed by these conclusions is that, except when the “Indian Tamils” of the plantation sector (who still suffer from various deprivations compared to other groups) are taken into account, up to about the third decade after independence, socio-economic stratifications—variations in wealth, income, power and privilege, or dichotomies such as those of “haves versus have-nots” or “exploiter versus exploited”—did not exhibit significant correspondences to the main ethnic differences in the country. And, there was certainly no economically “dominant” ethnic group.” (p. 436.)

Secondly, if the charge of “Genocide” is with respect to the period of the war, census data exists which indicate that between 1981 and 2001 (the period of the war) there was a substantial increase in the Tamil population in the Sinhalese-majority areas due to the migration of Tamils from the North-East to that area. Such a movement of Tamils could not have occurred if the Tamils were being subject to genocide.

Also, one can consider the fact that throughout the 30-year civil war, the salaries of government workers in the North and East, large parts of which were under the de facto control of the LTTE, were paid by the Government. Medicine, food, and other essentials were also sent to those areas throughout the conflict. All this does not bespeak an attempt at genocide, rather, the exact opposite.

Finally, if the charge of “Genocide” is with respect to the last phases of the war, i.e. January 2009 – May 2009, the undisputed fact that the security forces were able to rescue approximately 350,000 Tamils who were held hostage by the LTTE indicates the absence of “Genocide.” The Petitioner therefore draws the natural inference suggested by all of the facts set out above, namely, that the Tamils have not been subjected to genocide in this country.

Settlements

With respect to the accusation about settlements, the following facts are relevant. Firstly, if by “Tamil Nation” what the signatories mean is a territorial unit, what are the boundaries of this unit, and by what law is it recognized? If answers cannot be provided to these questions, then no “Tamil Nation” exists. If the existence of such a territorial unit cannot be established, the assertion that the intent behind the settlements is to destroy the “Tamil Nation” cannot be sustained, since that which does not exist cannot be destroyed.

Secondly, if by “Tamil Nation” the 3rd – 35th Respondents mean the areas of the island where Tamils comprise the majority ethnic group relative to the Sinhalese and the Muslims—i.e. the Northern and the Eastern Provinces—it is true that a certain number of Sinhalese settlements were established in the course of various development projects. Nevertheless, statistics exist in the public domain that show Tamil settlements were established along with the Sinhalese settlements, and that, taken as a whole, the distribution of the settlements, when considered in terms of area, as well as development project, was done in an equitable and fair fashion. (See for example, Professor K.M De Silva Separatist Ideology in Sri Lanka: A Historical Appraisal, 2nd ed. International Center for Ethnic Studies, 1995).

Thirdly, if the 3rd – 35th Respondents are claiming that settlements are being systematically established at present, it is incumbent on the 3rd – 35th Respondents to name what those settlements are, and to address the following matter: the Sri Lanka Constitution guarantees to every citizen, “Freedom of movement and of choosing one’s residence within Sri Lanka” (Art. 14(h)) which means that anyone who claims that Sinhalese settlements are illegal or wrong must show that those settlements are being established in excess of, or in ways that contravene, the aforesaid right.

The Petitioner repeats that, facts related to the points enumerated above are in the public domain. Therefore, the claim by the 3rd – 35th Respondents, that the Sinhalese are committing genocide against Tamils, and also imposing settlements to destroy the “Tamil Nation” are deliberate falsehoods, unless they can present some evidence to justify and explain their claims.

The Petitioner is of the view that, deliberate falsehoods such as the ones mentioned above can have only one result: the promotion of feelings of ill-will and hostility between different groups in this country, in this case the Sinhalese and the Tamils, and that if the signatories cannot produce evidence to justify and explain their claims, those claims show an ex facie intention to promote the said feelings of ill-will and hostility between Sinhalese and Tamil people.”

Conclusion

The stated purpose of Bill 104 is to ‘educate’ Ontarians about Tamil genocide. However, there is a grave danger that this will result in ‘mis-education’ of Ontarians along with Canadians in general, about the issue in question leading to a possible break-down in good relations between Canadians and Sri Lankans which should be a matter of concern for the Canadian Federal Government. Therefore, a substantive public discussion about whether or not Tamil genocide has occurred is urgently needed and this must necessarily involve giving Canadians a chance to ‘hear the other side’ of the story. Polwatta Gallage Niroshan’s case offers a good starting point from which to offer Canadians and other foreigners a glimpse into that ‘other side’.

(The writer is an Attorney-at-Law and consultant for the Strategic Communications Unit at the Lakshman Kadirgamar Institute.)

Features

Sri Lanka deploys 4,700 security personnel to protect electric fences amid human-elephant conflict

By Saman Indrajith

Sri Lanka has deployed over 4,700 Civil Security Force personnel to protect the electric fences installed to mitigate human-elephant conflict, Minister of Environment Dammika Patabendi told Parliament on Thursday.

The minister stated that from 2015 to 2024, successive governments have spent 906 million rupees (approximately 3.1 million U.S. dollars) on constructing elephant fences. During this period, 5,612 kilometers of electric fencing have been built.

He reported that between 2015 and 2024, 3,477 wild elephants and 1,190 people lost their lives due to human-elephant conflict. Electric fences remain a key measure in controlling this crisis, he added.

Between January 1 and 31, 2025, 43 elephants and three people have died as a result of such conflicts. Additionally, 21,468 properties have been damaged between 2015 and 2024, the minister noted.

Features

Electoral reform and abolishing the executive presidency

by Dr Jayampathy Wickramaratne,

President’s Counsel

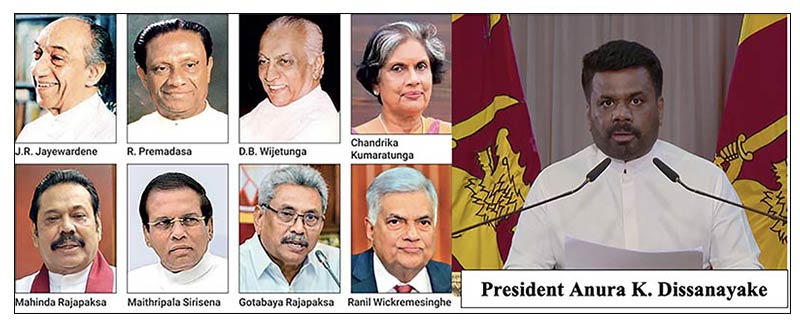

The Sri Lankan Left spearheaded the campaign against introducing the executive presidency and consistently agitated for its abolition. Abolition was a central plank of the platform of the National People’s Power (NPP) at the 2024 presidential elections and of the Janatha Vimukthi Peramuna (JVP) at all previous elections.

Issues under FPP or a mixed system

President Anura Kumara Dissanayake, participating in the ‘Satana’ programme on Sirasa TV, recently reiterated the NPP’s commitment to abolition and raised four issues related to accompanying electoral reform.

The first is that proportional representation (PR) did not, except in a few instances, give the ruling party a clear majority, resulting in a ‘weak parliament’. Therefore, electoral reform is essential when changing to a parliamentary form of government.

Secondly, ensuring that different shades of opinion and communities are proportionally represented may be challenging under the first-past-the-post system (FPP). For example, as the Muslim community in the Kurunegala district is dispersed, a Muslim-majority electorate will be impossible. Under PR, such representation is possible, as happened in 2024, with many Muslims voting for the NPP and its Muslim candidate.

The third issue is a difficulty that might arise under a mixed (FPP-PR) system. For example, the Trincomalee district returned Sinhala, Tamil and Muslim candidates at successive elections. In a mixed system, territorial constituencies would be fewer and ensuring representation would be difficult. For the unversed, there were 160 electorates that returned 168 members under FPP at the 1977 Parliamentary elections.

The fourth is that certain castes may not be represented under a new system. He cited the Galle district where some of the ‘old’ electorates had been created to facilitate such representation.

It might straightaway be said that all four issues raised by President Dissanayake have substantial validity. However, as the writer will endeavour to show, they do not present unsurmountable obstacles.

Proposals for reform, Constitutional Assembly 2016-18

Proposals made by the Steering Committee of the Constitutional Assembly of the 2015 Parliament and views of parties may be referred to.

The Committee proposed a 233-member First Chamber of Parliament elected under a Mixed-Member Proportional (MMP) system that seeks to ensure proportionality in the final allocation of seats. 140 seats (60%) will be filled by FPP. The Delimitation Commission may create dual-member constituencies and smaller constituencies to render possible the representation of communities of interest, whether racial, religious or otherwise. 93 compensatory seats (40%) will be filled to ensure proportionality. Of these, 76 will be filled by PR at the provincial level and 12 by PR at the national level, while the remaining 5 seats will go to the party that secures the highest number of votes nationally.

The Sri Lanka Freedom Party agreed with the proposals in principle, while the Joint Opposition (the precursor of the Sri Lanka Podujana Peramuna) did not make any specific proposals. The Tamil Nationalist Alliance was willing to consider any agreement between the two main parties on the main principles in the interest of reaching an acceptable consensus.

The Jathika Hela Urumaya’s position was interesting. If the presidential powers are to be reduced, the party obtaining the highest number of votes should have a majority of seats. Still, the representation of minor political parties should be assured. Therefore, the number of seats added to the winning party should be at the expense of the party placed second.

The All Ceylon Makkal Congress, Eelam People’s Democratic Party, Sri Lanka Muslim Congress and the Tamil Progressive Alliance jointly proposed that the principles of the existing PR system be retained but with elections being held for 40 to 50 electoral zones and a 2% cut-off point. The Janatha Vimukthi Peramuna was for the abolition of the executive presidency and, interestingly, suggested a mixed electoral system that ensures that the final outcome is proportional.

CDRL proposals

The Collective for Democracy and Rule of Law (CDRL), a group of professionals and academics that included the writer, made detailed proposals on constitutional reform in 2024. It proposed returning to parliamentary government. The legislature would be bicameral, with a House of Representatives of 200 members elected as follows: 130 members will be elected from territorial constituencies, including multi-member and smaller constituencies carved out to facilitate the representation of social groups of shared interest; Sixty members will be elected based on PR at a national or provincial level; Ten seats would be filled through national-level PR from among parties that failed to secure a seat through territorial constituencies or the sixty seats mentioned above, enabling small parties with significant national presence without local concentration to secure representation. Appropriate provisions shall be made to ensure adequate representation of women, youth and underrepresented interest groups.

The writer’s proposal

The people have elected the NPP leader as President and given the party a two-thirds majority in Parliament. It is, therefore, prudent to propose a system that addresses the concerns expressed by the President. Otherwise, we will be going around in circles. The writer believes that the CDRL proposals, suitably modified, present a suitable basis for further discussion.

While the people vehemently oppose any increase in the number of MPs, it would be challenging to address the President’s concerns in a smaller parliament. The writer’s proposal is, therefore, to work within a 225-member Parliament.

The writer proposes that 150 MPs be elected through FPP and 65 through national PR. 10 seats would be filled through national-level PR from among parties that have not secured a seat either through territorial constituencies or the 65 seats mentioned above. The Delimitation Commission shall apportion 150 members among the various provinces proportionally according to the number of registered voters in each province. The Commission will then divide each province into territorial constituencies that will return the number of MPs apportioned. The Commission may create smaller constituencies or multi-member constituencies to render possible the representation of social groups of shared interest.

The 65 PR seats will be proportionally distributed according to the votes received by parties nationally, without a cut-off point. The number of ‘PR MPs’ that a party gets will be apportioned among the various provinces in proportion to the votes received in the provinces. For example, if Party A is entitled to 10 PR seats and has obtained 20% of its total vote from the Central Province, it will fill 2 PR seats from candidates from that Province, and so on. Each party shall submit names of potential ‘PR MPs’ from each of the provinces where the party contests at least one constituency in the order of its preference, and seats allotted to that party in a given province are filled accordingly. The remaining 10 seats will be filled by small parties as proposed by the CDRL.

How does the proposed system address President Dissanayake’s concerns?

The President’s concern that PR will result in a weak parliament is sufficiently addressed when a majority of MPs are elected under FPP.

Before dealing with the other three issues, it must be said that voters do not always vote for candidates from their communities. A classic example is the 1965 election result in Balapitiya, a Left-oriented constituency dominated by a particular caste. The Lanka Sama Samaja Party boldly nominated L.C. de Silva, from a different caste, to contest Lakshman de Silva, a long-standing MP who crossed over to bring down the SLFP-LSSP coalition. Balapitiya voters punished Lakshman and elected L.C.

Multi-member constituencies have generally served their purpose but not always. The Batticaloa dual-member constituency had been created to ‘render possible’ the election of a Tamil and a Muslim. At the 1970 elections, the four leading candidates were Rajadurai of the Federal Party, Makan Markar of the UNP, Rahuman of the SLFP and the independent Selvanayagam. The Muslim vote was closely split between Macan Markar and Rahuman, resulting in both losing. Muslim voters surely knew that a split might deny Muslim representation but preferred to vote according to their political convictions.

The President’s second concern that a dispersed community may not get representation under FPP will also be addressed better under the proposed system. Taking the same Kurunegala district as an example, a party could attract Muslim voters by placing a Muslim high up on the PR list. Similarly, a Tamil party could place a candidate from a depressed community high up in its Northern Province PR list to attract voters of depressed communities and ensure their representation.

The third concern was that the number of electorates would be less under a mixed system, making it challenging to carve out electorates to facilitate the representation of communities, the Trincomalee district being an example. Empowering the Delimitation Commission to create smaller electorates assuages this concern. It will not be Trincomalee District but the whole Eastern Province to which a certain number of FPP MPs will be allotted, giving the Commission broad discretion to carve out electorates. The Commission could also create multimember constituencies to render possible the representation of communities of interest. The fourth concern about caste representation would also be addressed similarly.

It may be noted that the difference between the number of FPP MPs (150) under the proposed system is only 10% less than that under the delimitation of 1975 (168). Also, there will be no cut-off point for PR as against the present cut-off of 5%. This will help small as well as not-so-small parties. Reserving 10 seats for small parties also helps address the concerns of the President.

No spoilers, please. Don’t let electoral reform be an excuse for a Nokerena Wedakama

The writer submits the above proposals as a basis for discussion. While a stable government and the representation of various interests are essential, abolishing the dreaded Executive Presidency is equally important. These are not mutually exclusive.

President Dissanayake also said on Sirasa TV that once the local elections are over, the NPP would first discuss the issue internally. This is welcome as there would be a government position, which can be the basis for further discussion.

This is the first time a single political party committed to abolition has won a two-thirds majority. Another such opportunity will almost certainly not come. Let there be no spoilers from either side. Let electoral reform not be an excuse for retaining the Executive Presidency. Let the Sinhala saying ‘nokerena veda kamata konduru thel hath pattayakuth thava tikakuth onalu’ not apply to this exercise (‘for the doctoring that will never come off, seven measures and a little more, of the oil of eye-flies are required’—translation by John M. Senaveratne, Dictionary of Proverbs of the Sinhalese, 1936).

According to recent determinations of the Supreme Court, a change to a parliamentary form of government requires the People’s approval at a referendum. While the NPP has a two-thirds majority, it should not take for granted a victory at a referendum held late in the term of Parliament for, then, there is the danger of a referendum becoming a referendum on the government’s performance rather than one on the constitutional bill, with opposition parties playing spoilers. If the government wishes to have the present form of government for, say, four years, it could now move a bill for abolition with a sunset clause that provides for abolition on a specified date. Delay will undoubtedly frustrate the process and open the government to the accusation that it indulged in a ‘nokerena vedakama’.

Features

Did Rani miss manorani ?

(A film that avoids the ‘Mannerism’ of a Biopic: Rani)

by Bhagya Rajapakshe

bhagya8282@gmail.com

This is only how Manorani sees Richard. It doesn’t have a lot of what Richard did. Although Manorani is not someone who pays attention to the happenings in the country. It was only after her son was kidnapped that she began to feel that this was happening in the country.She had human emotions. But she was a person who smoked cigarettes and drank whiskey and lived a merry life.”

(Interview with “Rani” film director Ashoka Handagama by Upali Amarasinghe – 02.02.2025 ‘Anidda’ weekend newspaper, pages 15 and 19)

The above statement shows the key attitude of the director of the movie, “Rani” towards the central character of the film, Dr. Manorani Sarawanamuttu. This statement is highly controversial. Similarly, the statement given by the director to Groundviews on 30.01.2025 about capturing the depth of Rani’s character shows that he has done so superficially, frivolously?

A biopic is a specific genre of cinema. This genre presents true events in the life of a person (a biography), or a group of people who are currently alive or who belong to history with recognisable names. The biopic genre often artistically and cinematically explores keenly the main character along with a few secondary characters connected to the central figure. World cinema is proof that even if the characters are centuries old, they are carefully researched and skilled directors take care to weave the biographies into their films without causing any harm or injustice to the original character.

According to the available authentic reports, Manorani Saravanamuthu was a professionally responsible medical doctor. Chandri Peiris, a close friend of her family, in his feature article on Manorani in the ‘Daily Mirror’ newspaper on 06th November 2021, says this about her:

“She was a doctor who had her surgeries in the poorest areas around Colombo which made her popular with communities who preferred their women to be seen by female doctors. She had a wonderful manner with her patients which my mother described by saying, ‘looking at her is enough to make you well …. When it came to our outlandish group of friends, she was always there to steer many of us through some very personal issues such as: unplanned pregnancies, teenage pregnancies, mental breakdowns, STD’s, young lovers who ran away and married, depression, circumcisions, break-ups, fractures, dance injuries, laryngitis (especially among the actors and singers) fevers, pimples, and even the odd boil on the bum.”

But the image of Rani depicted by Handagama in his film is completely different from this. According to the film, a major feature of her life consisted of drinking whiskey and smoking cigarettes. Her true role is unspoken, hidden in the film. A grave question arises as to whether the director spent adequate time doing the research? to find out who Manorani really was. In his article Chandri Peiris further says the following about Manorani:

“Soon after the race riots in 1983, Manorani (along with Richard) helped a great many Sri Lankan Tamils to find refuge in countries all over the world. Nobody knew about this. But all of us who used to hang around their house kept seeing unfamiliar people come over to stay a few days and then leave. Among them were the three sons of the Master-in-Charge of Drama at S. Thomas’ College, who were swiftly sent abroad by the tireless efforts of this mother and son. It was then that we worked out that their home was a safehouse. … Manorani was vehemently opposed to the terror wreaked by the LTTE and always wanted Sri Lanka to be one country that was home to the many diverse cultures within it. When the ethnic strife developed into a full-on war with those who wanted to create a separate state for Tamil Eelam, she remained completely against it.”

According to the director of the film, if Rani had no awareness of what was happening in the country and the world, how could she have helped the victims survive and leave the country during that life-threatening period? It is clear from all this that the director has failed to fully study the character of Manorani and what she did. There is a scene where Manorani watches a Sinhala stage play with much annoyance and on her way back home with Richard, she is shown insensitively avoiding Richard’s friend Gayan being assaulted by a mob. This demeanour does not match the actual reports and information published about Manorani. How did the director miss these records? It shows his indifference to researching background information for a film such as this. He clearly does not think that research is essential for a sharp-witted artist in creating his artwork. In his own words, he told the Anidda newspaper:

“But the information related to this is in the public domain and the challenge I had was to interpret that information in the way I wanted. I am not an investigative journalist; My job is to create a work of art. That difference should be understood and made.”

And according to the director, “I was invited to do the film in 2023. The script was written within two to three months and the shooting was planned quickly.” Thus, it is clear that there has been no time to study the inner details related to Manorani, the main character of the film, or the character’s Mannerism. Professor Sarath Chandrajeewa, who published a book with two critical reviews on Handagama’s previous film ‘Alborada’, emphasises in both, that ‘Alborada’ also became weak due to the lack of proper research work’ (Lamentation of the Dawn (2022), pages 46-57).

Directors working in the biopic genre with a degree of seriousness consider it their responsibility to study deeply and construct the ‘mannerism’ of such central characters to create a superior biographical film. For example, in Kabir Khan’s 2021 film ’83’ the actor Tahir Raj Bhasin, who played the role of Sunil Gavaskar, said that it took him six months to study Sunil Gavaskar’s unique style characteristics or Mannerism.

Also, Austin Butler, the actor who played the role of Elvis Presley in the movie ‘Elvis’ directed by Buz Luhrmann and released in 2022, said in a news conference: After he started studying the character of Elvis, he became obsessed with the character, without meeting or talking to his family for nearly one year, while making the film in Australia before, during Covid and after.

‘Oppenheimer’ (2023) was written and directed by Christopher Nolan, in which Cillian Murphy plays the role of Oppenheimer. Nolan read and studied the 700-page story about Oppenheimer called ‘American Prometheus’ . It is said that it took three months to write the script and 57 days for shooting, and finally a two-hour film was created. The rejection of such intense studies by our filmmakers will determine the future of cinema in this country.

Acting is the prime aspect of a movie. The character of Manorani is performed very skillfully in the movie. But certain of her characteristics and mannerism become repetitive and in their very repetitiveness become tiresome to watch. For example, right across the film Manorani is shown smoking, drinking alcohol, sitting and thinking, going towards a window and thinking and smoking again. It would have been better if it had been edited. The audience is thereby given the impression that Manorani lives on cigarettes and whiskey. Although smoking and drinking alcohol is a common practice among some women of Manorani’s social class, it is depicted in the film so repetitively that it creates a sense of revulsion in the viewer. In the absence of close-ups and a play of light and dark, Manorani’s mental states cannot be seen in their intense three dimensionality. It is a question whether the director gave up directing and let the actress play the role of Manorani as she wished. At the beginning of the film, close-ups of Manorani appear with the titles but gradually become normal camera angles in the film. This avoids the use of close-ups of Manorani’s face to show emotion in the most shocking moments in the film. Below are some films that demonstrate this cinematic technique well.

‘Three Colours: Blue’ (1993) French, Directed by Kryzysztof Kies’lowski.

‘Memories in March’

(2010) Indian, Directed by Sanjoy Nag.

‘Manchester by the Sea’

(2016) English, Directed by Keneth Lonergan.

‘Collateral Beauty’

2016) English, Directed by David Frankel.

Certain characters appear in the film without any contribution to building Manorani’s role. Certain scenes such as the Television news, bomb explosions, dialogue scenes where certain characters interview Manorani are not integrated into the film’s narrative and feel forced. The scene with the group of hooligans in a jeep at the end of the film is like a strange tail to the film.

Richard’s sexual orientation, which is hinted at the end of the film by these thugs in the final scene, is an insult to him. It is a great disrespect to those characters to present facts without strong information analysis and to tell the inner life of those characters while presenting a real character through an artwork with real names. The director should not have done such humour and humiliation.

There is some thrill in seeing actors who resemble the main political personalities of that era playing those roles in the film. In this the film has more of a documentary than a fictional quality but it barely marks the socio-political history of this country during the period of terror in 88-89. The character of Manorani was created as a person floating in that history ungrounded, without a sense of gravity.

The film’s music and vocals are mesmerising. But unfortunately, the song ‘Puthune’ (Dearest Son), which has a very strong lyrical composition, melody and singing, is placed at the end of the film, so the audience does not know its strength. This is because the audience starts to leave the cinema as soon as the song starts, when the closing credits scrolled down. If the song had accompanied the scene on the beach where we see Manorani for the last time, the audience would have felt its strength.

Manorani’s true personality was a unique blend of charm, sensitivity, compassion, intelligence, warmth and fun, which enhanced her overall beauty, as evidenced by various written accounts of her. Art critics and historians H. W. Johnson and Anthony F. A Johnson state in their book ‘History of Art’ (2001), “Every work of art tells whether it is artistic or not. And the grammar and structure of the form will signal to us that.”

-

Business5 days ago

Business5 days agoSri Lanka’s 1st Culinary Studio opened by The Hungryislander

-

Sports6 days ago

Sports6 days agoHow Sri Lanka fumbled their Champions Trophy spot

-

Features6 days ago

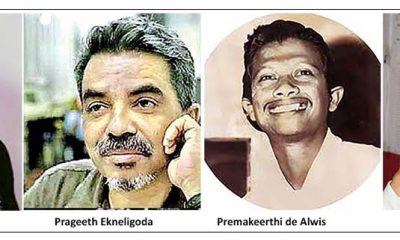

Features6 days agoThe Murder of a Journalist

-

Sports6 days ago

Sports6 days agoMahinda earn long awaited Tier ‘A’ promotion

-

Features6 days ago

Features6 days agoExcellent Budget by AKD, NPP Inexperience is the Government’s Enemy

-

Sports5 days ago

Sports5 days agoAir Force Rugby on the path to its glorious past

-

News6 days ago

News6 days agoSri Lanka’s first ever “Water Battery”

-

Features5 days ago

Features5 days agoRani’s struggle and plight of many mothers