Features

Nihal Jayawickrema discusses the judiciary and human rights with the Anglo American Lawyer magazine

Dr. Nihal Jayawickrama was the Ariel F. Sallows Professor of Human Rights at the University of Saskatchewan, Canada, and Associate Professor of Law at the University of Hong Kong, where he taught both constitutional law and the international law of human rights. He was also Chair of JUSTICE: the Hong Kong Section of the International Commission of Jurists, Executive Director of Transparency International Berlin, Chair of the Trustees of the Commonwealth Human Rights Initiative, London, and a Member of the Permanent Court of Arbitration at The Hague.

A member of the Sri Lanka Bar, he held the offices of Attorney General, and Permanent Secretary to the Ministry of Justice, having been appointed to that office at the age of 32. He was Vice-Chairperson of the Sri Lanka delegation to the United Nations General Assembly and served on the Third Committee which dealt with human rights issues. He is the Coordinator/Rapporteur of the UN sponsored Judicial Integrity Group which formulated the Bangalore Principles of Judicial Conduct and related instruments.

The AAL Magazine: Dr. Nihal Jayawickrama, we are truly honored by your consent to have a conversation with you especially on your book Judicial Application of Human Rights published by the Cambridge University Press which is now on its second edition. You have touched almost all the topics on human rights. I would say a very comprehensive book on human rights covering jurisprudence of the UN Human Rights monitories bodies. One reason is that you have had a long association with law – runs to around five decades – having been a Professor of Law and your abiding interest in promoting constitutional and human rights especially in Sri Lanka. If I may ask Sir, what really inspired you to write a book on the judicial application of human rights?

Dr. Jayawickrama: In 1978, shortly after I resigned from the Ministry of Justice following a change of government, I was asked by Mr. Paul Sieghart, a prominent Barrister in the United Kingdom and Chairman of JUSTICE, UK, whom I knew, whether I would be interested in researching the emerging body of international human rights law for a book which he proposed to write. I would be appointed a Research Fellow at King’s College, University of London, under the supervision of Professor James Fawcett, then President of the European Commission of Human Rights. I was also informed that the University was willing to enroll me to read for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy if I wished to apply the results of my research in an appropriate way. I accepted both offers. My research on the jurisprudence of the Strasbourg institutions and of national courts was incorporated in Paul Sieghart’s pioneering work, The International Law of Human Rights, which was published by Oxford University Press in 1983. My thesis, which critically examined the governance of post-independence Ceylon/Sri Lanka by reference to international human rights standards, was accepted by the University for the award of the degree of Ph.D.

When I was nine years old, my parents were persuaded by my mother’s brother that I should leave my primary school in the southern town of Galle, and continue my education in his old school, Royal College, Colombo. Consequently, I lived in my uncle’s home in Colombo for the next 19 years, until my marriage in 1965. Meanwhile, my uncle who was a Crown Counsel became Attorney-General, Judge of the Supreme Court, and President of the Court of Final Appeal. He was also the President of the Geneva-based International Commission of Jurists. Justice T.S. Fernando Q.C., had a profound influence on my life. It was at our dinner table that I was introduced to the concept of human rights. His commitment to human rights in whatever capacity he served the State led to my own study of the subject and its application, both in the practice of my profession and in my capacity as the administrative head of the Ministry of Justice.

After I introduced a course on Human Rights Law at the University of Hong Kong, I found that the international human rights regime had strengthened considerably in the decade following the publication of Paul Sieghart’s book. More than 150 countries, spread over every continent had incorporated contemporary human rights standards into their legal systems. More than 100 countries had ratified the Optional Protocol to the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, thereby enabling their inhabitants to access the Human Rights Committee. Nearly all the countries of South and Central America had subscribed to the Inter-American Convention on Human Rights. The resulting jurisprudence had added a new dimension to the concepts that were first articulated in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. Unfortunately, Paul Sieghart passed away in 1989. I offered to update his pioneering work, but Oxford University Press was not interested. Cambridge University Press, on the other hand, immediately recognized the need for what they described as “a definitive text on the subject”.

Writing a book which runs into over a thousand pages is difficult to combine with regular teaching at a university, as I soon discovered after I commenced preliminary work on it in Hong Kong. Fortunately, the privilege that the University of Saskatchewan accorded me, by nominating me to the Ariel F. Sallows Chair of Human Rights, enabled me to commence my writing in the exhilarating climate of the Canadian prairies. The first edition of my book was published in 2002, and the second edition in 2017.

The AAL Magazine: Why do you think human rights should be protected by the government and why do you think citizens should pursue their rights if governments have been lethargic on the political will to protect the rights of people?

Dr. Jayawickrama: Respect for human dignity and personality and a belief in justice are rooted deep in the religious and cultural traditions of the world. Hinduism, Buddhism, Judaism, Christianity, and Islam all stress the inviolability of the essential attributes of humanity. This religious and cultural tradition was complemented by many strands of philosophical thought that unfolded the concept of a natural law that was equally inviolable and to which all man-made law must conform. Philosophy began transforming into Law in historic documents such as the Magna Carta of 1215, the English Bill of Rights of 1689, the American Declaration of Independence of 1776, and the French Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen of 1789. However, it was the Second World War, and the events that preceded it in Germany, and in the territories under German occupation, where unprecedented atrocities were perpetrated on millions of its own people by the regime then lawfully in power, that led to the establishment of a set of superior standards to which all national law must conform – an overriding code of international human rights law.

The Charter of the United Nations was the standard-bearer. The member states of the United Nations have pledged themselves to act, both collectively and separately within their domestic jurisdictions, to secure universal respect for, and observance of, human rights and fundamental freedoms for all without distinction as to race, sex, language, or religion. That is a legal obligation undertaken by the member states of the UN. The people, therefore, have the right to demand of their governments that the basic legal framework be established, and appropriate action be taken, to enable them to exercise and enjoy their fundamental human rights.

The AAL Magazine: The HR jurisprudence you had referred to in your book is quite comprehensive. It covers over 103 countries which is quite an exhaustive exercise. Which jurisdiction did you find most interesting in terms of the articulation of the rights, judicial reasoning or the remedies proposed by the different types of courts eg; in Europe , Latin America, India Australasia, South Africa or any other jurisdiction. You have mentioned that ‘jurisprudence rich in content and varied in flavor, from diverse cultural traditions, has added a new dimension to the concepts first articulated in the UDHR’. Could you please elaborate? Did you identify any methodology which is more prevalent in some jurisdictions but not in others etc.

Dr. Jayawickrama: At the international level, the Human Rights Committee established under the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights has been the principal source of jurisprudence. At the regional level, the European Court and Commission of Human Rights and the Inter-American Court and Commission of Human Rights have been the principal sources. The Judicial Committee of the Privy Council has also played a significant role in interpreting and applying the Bills of Rights contained in the constitutions of British colonial territories. At the national level, the Supreme Courts of India and Canada, and the Constitutional Court of South Africa have made unique contributions towards the interpretation and application of civil and political rights. I should, however, mention that the Table of Cases on which I have drawn extends to 140 pages, and these include the decisions of superior courts in over a hundred countries from the Pacific to the Caribbean, and especially the Constitutional Courts in European States, all of which have also contributed to extending the frontiers of human dignity and freedom.

If I may give an example: the Universal Declaration of Human Rights proclaimed in 1948 that “Everyone has the Right to Life”. Article 6 of the ICCPR required that “This right shall be protected by law”, and that “No one shall be arbitrarily deprived of his life”. It recognized the death penalty as an exception and explained the circumstances in which it could be carried out. Of course, some years later, in the Second Optional Protocol, it expressly required the abolition of the death penalty. Meanwhile, through judicial interpretation, the application of Article 6 was extended to cover the unborn child; mentally or disabled persons; the aged, senile, and terminally ill persons; persons in detention; the extradition or deportation of persons; the concept of a healthy environment; access to medical services; war and nuclear weapons; and involuntary disappearances. The Supreme Court of India has described the right to life as taking within its sweep the right to food, the right to clothing, the right to a decent environment, and the right to a reasonable accommodation to live in. That Court also held that the right to life includes the right to livelihood.

The AAL Magazine: As you are well aware, the realization of economic, social and cultural rights are predicated on Government policies. However, reviewing Government policies that are consistent or inconsistent with constitutional principles and obligations under international human rights law is clearly a prerogative of the judiciary. While the judicial activism and attitudes in reviewing Government policy may vary from country to country, I suppose policy review is not policymaking. Do you think by taking decisions based on economic, social, and cultural rights would be seen as being overstepping its constitutional role. How does judicial activism come into play by ensuring such rights are upheld?

Dr. Jayawickrama: International law recognizes not only what may be described as civil and political rights, but also economic, social, and cultural rights. Sri Lanka, as a state party to the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, has made a commitment to take measures to progressively achieve the realization of these rights for its citizens. Unfortunately, our Constitution does not recognize these as enforceable rights. Instead, it regards their achievement as “directive principles of state policy” which are not enforceable in any court. These rights are no less important than civil and political rights and are constitutionally protected in many countries.

To give a few examples: The right to work has been interpreted to imply a right not to be arbitrarily prevented from working as, for example, in a country in which the law requires a woman to obtain the permission of her husband in order to work. Also incompatible with this right is the requirement of a female civil servant to resign on marriage. The judicial interpretation of this right has led to the prohibition of forced labour; equitable, just, and reasonable wages; equal remuneration for work of equal value; safe and healthy working conditions; and equal opportunities for promotion. Therefore, I do not agree that the judiciary would be overstepping its constitutional role if it is called upon to monitor compliance by the government of economic, social, and cultural rights that are constitutionally guaranteed. After all, they cover such vital issues in peoples’ lives such as the right to adequate food; freedom from hunger; right to adequate housing; protection from forced evictions; access to sufficient water; right to social security; maternal child and reproductive health; environmental and industrial hygiene; and the right to academic freedom.

(To be continued)

(Mr. Srinath Fernando is the editor of the AAL magazine from which this article was excerpted)

Features

Recruiting academics to state universities – beset by archaic selection processes?

Time has, by and large, stood still in the business of academic staff recruitment to state universities. Qualifications have proliferated and evolved to be more interdisciplinary, but our selection processes and evaluation criteria are unchanged since at least the late 1990s. But before I delve into the problems, I will describe the existing processes and schemes of recruitment. The discussion is limited to UGC-governed state universities (and does not include recruitment to medical and engineering sectors) though the problems may be relevant to other higher education institutions (HEIs).

How recruitment happens currently in SL state universities

Academic ranks in Sri Lankan state universities can be divided into three tiers (subdivisions are not discussed).

* Lecturer (Probationary)

– recruited with a four-year undergraduate degree. A tiny step higher is the Lecturer (Unconfirmed), recruited with a postgraduate degree but no teaching experience.

* A Senior Lecturer can be recruited with certain postgraduate qualifications and some number of years of teaching and research.

* Above this is the professor (of four types), which can be left out of this discussion since only one of those (Chair Professor) is by application.

State universities cannot hire permanent academic staff as and when they wish. Prior to advertising a vacancy, approval to recruit is obtained through a mind-numbing and time-consuming process (months!) ending at the Department of Management Services. The call for applications must list all ranks up to Senior Lecturer. All eligible candidates for Probationary to Senior Lecturer are interviewed, e.g., if a Department wants someone with a doctoral degree, they must still advertise for and interview candidates for all ranks, not only candidates with a doctoral degree. In the evaluation criteria, the first degree is more important than the doctoral degree (more on this strange phenomenon later). All of this is only possible when universities are not under a ‘hiring freeze’, which governments declare regularly and generally lasts several years.

Problem type 1

– Archaic processes and evaluation criteria

Twenty-five years ago, as a probationary lecturer with a first degree, I was a typical hire. We would be recruited, work some years and obtain postgraduate degrees (ideally using the privilege of paid study leave to attend a reputed university in the first world). State universities are primarily undergraduate teaching spaces, and when doctoral degrees were scarce, hiring probationary lecturers may have been a practical solution. The path to a higher degree was through the academic job. Now, due to availability of candidates with postgraduate qualifications and the problems of retaining academics who find foreign postgraduate opportunities, preference for candidates applying with a postgraduate qualification is growing. The evaluation scheme, however, prioritises the first degree over the candidate’s postgraduate education. Were I to apply to a Faculty of Education, despite a PhD on language teaching and research in education, I may not even be interviewed since my undergraduate degree is not in education. The ‘first degree first’ phenomenon shows that universities essentially ignore the intellectual development of a person beyond their early twenties. It also ignores the breadth of disciplines and their overlap with other fields.

This can be helped (not solved) by a simple fix, which can also reduce brain drain: give precedence to the doctoral degree in the required field, regardless of the candidate’s first degree, effected by a UGC circular. The suggestion is not fool-proof. It is a first step, and offered with the understanding that any selection process, however well the evaluation criteria are articulated, will be beset by multiple issues, including that of bias. Like other Sri Lankan institutions, universities, too, have tribal tendencies, surfacing in the form of a preference for one’s own alumni. Nevertheless, there are other problems that are, arguably, more pressing as I discuss next. In relation to the evaluation criteria, a problem is the narrow interpretation of any regulation, e.g., deciding the degree’s suitability based on the title rather than considering courses in the transcript. Despite rhetoric promoting internationalising and inter-disciplinarity, decision-making administrative and academic bodies have very literal expectations of candidates’ qualifications, e.g., a candidate with knowledge of digital literacy should show this through the title of the degree!

Problem type 2 – The mess of badly regulated higher education

A direct consequence of the contemporary expansion of higher education is a large number of applicants with myriad qualifications. The diversity of degree programmes cited makes the responsibility of selecting a suitable candidate for the job a challenging but very important one. After all, the job is for life – it is very difficult to fire a permanent employer in the state sector.

Widely varying undergraduate degree programmes.

At present, Sri Lankan undergraduates bring qualifications (at times more than one) from multiple types of higher education institutions: a degree from a UGC-affiliated state university, a state university external to the UGC, a state institution that is not a university, a foreign university, or a private HEI aka ‘private university’. It could be a degree received by attending on-site, in Sri Lanka or abroad. It could be from a private HEI’s affiliated foreign university or an external degree from a state university or an online only degree from a private HEI that is ‘UGC-approved’ or ‘Ministry of Education approved’, i.e., never studied in a university setting. Needless to say, the diversity (and their differences in quality) are dizzying. Unfortunately, under the evaluation scheme all degrees ‘recognised’ by the UGC are assigned the same marks. The same goes for the candidates’ merits or distinctions, first classes, etc., regardless of how difficult or easy the degree programme may be and even when capabilities, exposure, input, etc are obviously different.

Similar issues are faced when we consider postgraduate qualifications, though to a lesser degree. In my discipline(s), at least, a postgraduate degree obtained on-site from a first-world university is preferable to one from a local university (which usually have weekend or evening classes similar to part-time study) or online from a foreign university. Elitist this may be, but even the best local postgraduate degrees cannot provide the experience and intellectual growth gained by being in a university that gives you access to six million books and teaching and supervision by internationally-recognised scholars. Unfortunately, in the evaluation schemes for recruitment, the worst postgraduate qualification you know of will receive the same marks as one from NUS, Harvard or Leiden.

The problem is clear but what about a solution?

Recruitment to state universities needs to change to meet contemporary needs. We need evaluation criteria that allows us to get rid of the dross as well as a more sophisticated institutional understanding of using them. Recruitment is key if we want our institutions (and our country) to progress. I reiterate here the recommendations proposed in ‘Considerations for Higher Education Reform’ circulated previously by Kuppi Collective:

* Change bond regulations to be more just, in order to retain better qualified academics.

* Update the schemes of recruitment to reflect present-day realities of inter-disciplinary and multi-disciplinary training in order to recruit suitably qualified candidates.

* Ensure recruitment processes are made transparent by university administrations.

Kaushalya Perera is a senior lecturer at the University of Colombo.

(Kuppi is a politics and pedagogy happening on the margins of the lecture hall that parodies, subverts, and simultaneously reaffirms social hierarchies.)

Features

Talento … oozing with talent

This week, too, the spotlight is on an outfit that has gained popularity, mainly through social media.

This week, too, the spotlight is on an outfit that has gained popularity, mainly through social media.

Last week we had MISTER Band in our scene, and on 10th February, Yellow Beatz – both social media favourites.

Talento is a seven-piece band that plays all types of music, from the ‘60s to the modern tracks of today.

The band has reached many heights, since its inception in 2012, and has gained recognition as a leading wedding and dance band in the scene here.

The members that makeup the outfit have a solid musical background, which comes through years of hard work and dedication

Their portfolio of music contains a mix of both western and eastern songs and are carefully selected, they say, to match the requirements of the intended audience, occasion, or event.

Although the baila is a specialty, which is inherent to this group, that originates from Moratuwa, their repertoire is made up of a vast collection of love, classic, oldies and modern-day hits.

The musicians, who make up Talento, are:

Prabuddha Geetharuchi:

(Vocalist/ Frontman). He is an avid music enthusiast and was mentored by a lot of famous musicians, and trainers, since he was a child. Growing up with them influenced him to take on western songs, as well as other music styles. A Peterite, he is the main man behind the band Talento and is a versatile singer/entertainer who never fails to get the crowd going.

Geilee Fonseka (Vocals):

A dynamic and charismatic vocalist whose vibrant stage presence, and powerful voice, bring a fresh spark to every performance. Young, energetic, and musically refined, she is an artiste who effortlessly blends passion with precision – captivating audiences from the very first note. Blessed with an immense vocal range, Geilee is a truly versatile singer, confidently delivering Western and Eastern music across multiple languages and genres.

Chandana Perera (Drummer):

His expertise and exceptional skills have earned him recognition as one of the finest acoustic drummers in Sri Lanka. With over 40 tours under his belt, Chandana has demonstrated his dedication and passion for music, embodying the essential role of a drummer as the heartbeat of any band.

Harsha Soysa:

(Bassist/Vocalist). He a chorister of the western choir of St. Sebastian’s College, Moratuwa, who began his musical education under famous voice trainers, as well as bass guitar trainers in Sri Lanka. He has also performed at events overseas. He acts as the second singer of the band

Udara Jayakody:

(Keyboardist). He is also a qualified pianist, adding technical flavour to Talento’s music. His singing and harmonising skills are an extra asset to the band. From his childhood he has been a part of a number of orchestras as a pianist. He has also previously performed with several famous western bands.

Aruna Madushanka:

(Saxophonist). His proficiciency in playing various instruments, including the saxophone, soprano saxophone, and western flute, showcases his versatility as a musician, and his musical repertoire is further enhanced by his remarkable singing ability.

Prashan Pramuditha:

(Lead guitar). He has the ability to play different styles, both oriental and western music, and he also creates unique tones and patterns with the guitar..

Features

Special milestone for JJ Twins

The JJ Twins, the Sri Lankan musical duo, performing in the Maldives, and known for blending R&B, Hip Hop, and Sri Lankan rhythms, thereby creating a unique sound, have come out with a brand-new single ‘Me Mawathe.’

In fact, it’s a very special milestone for the twin brothers, Julian and Jason Prins, as ‘Me Mawathe’ is their first ever Sinhala song!

‘Me Mawathe’ showcases a fresh new sound, while staying true to the signature harmony and emotion that their fans love.

This heartfelt track captures the beauty of love, journey, and connection, brought to life through powerful vocals and captivating melodies.

It marks an exciting new chapter for the JJ Twins as they expand their musical journey and connect with audiences in a whole new way.

Their recent album, ‘CONCLUDED,’ explores themes of love, heartbreak, and healing, and include hits like ‘Can’t Get You Off My Mind’ and ‘You Left Me Here to Die’ which showcase their emotional intensity.

Readers could stay connected and follow JJ Twins on social media for exclusive updates, behind-the-scenes moments, and upcoming releases:

Instagram: http://instagram.com/jjtwinsofficial

TikTok: http://tiktok.com/@jjtwinsmusic

Facebook: http://facebook.com/jjtwinssingers

YouTube: http://youtube.com/jjtwins

-

Opinion4 days ago

Opinion4 days agoJamming and re-setting the world: What is the role of Donald Trump?

-

Features4 days ago

Features4 days agoAn innocent bystander or a passive onlooker?

-

Features5 days ago

Features5 days agoRatmalana Airport: The Truth, The Whole Truth, And Nothing But The Truth

-

Features6 days ago

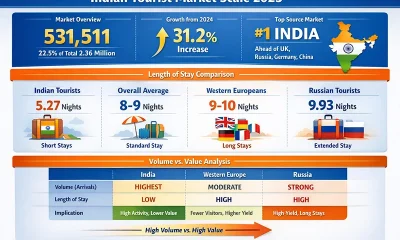

Features6 days agoBuilding on Sand: The Indian market trap

-

Opinion6 days ago

Opinion6 days agoFuture must be won

-

Business6 days ago

Business6 days agoDialog partners with Xiaomi to introduce Redmi Note 15 5G Series in Sri Lanka

-

Business5 days ago

Business5 days agoIRCSL transforms Sri Lanka’s insurance industry with first-ever Centralized Insurance Data Repository

-

Opinion1 day ago

Opinion1 day agoSri Lanka – world’s worst facilities for cricket fans