Features

Narrow escape from JVP in 1971

Excerpted from the Memoirs of Chandra Wickremasingha, Retd. Additional Secy. to the President

The work in the Settlement Dept. involved camping out in remote areas of the island where land still remained unsettled. Following colonial tradition and standards, the Dept. had comfortable carpeted tents which were pitched at the chosen site by an advance party comprising two labourers and a cook.At the start I enjoyed the novelty of camping out in picturesque rural areas and going into the claims made by villagers. Where I entertained doubts about certain claims, the particular lands were visited by me in the company of an officer of the Dept. still carrying the rather pompous title -‘Interpreter Mudaliyar’, and the Village Headman (Grama Niladhari) of the locality.

There were also extravagant, spurious claims made by interlopers to the area, which were summarily dismissed on visiting these properties. The Statute was so powerful that once an order settling a land on a person was made by the Settlement Officer, it could not be challenged or set aside, even by the Supreme Court. This Act was one of those residual colonial legacies which somehow continued to remain unexpunged from the Statute Book, well into my time.

I am told that the wide powers in settling land enjoyed by Settlement Officers of yesteryear, are now drastically circumscribed by new laws that short circuit the rather reliable yet cumbersome process of settlement inquiries and provide for land to be settled on the basis of title registration following a relatively cursory examination of claims.

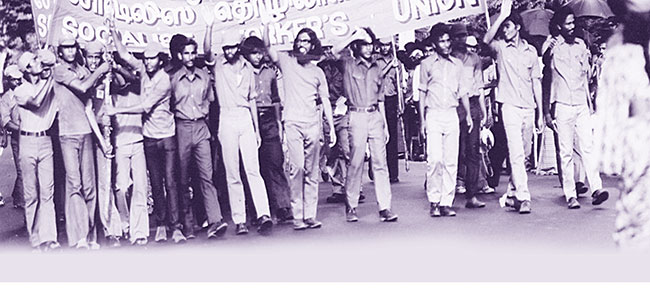

The JVP insurrection of 1971

It was while camping out in Dambagalla, a village off Moneragala sometime in April 1971that I learnt about the initial JVP attack on a Police Station at Wellawaya. The Grama Sevaka who seemed aware that the surrounding  area was infested by JVP types, advised me to leave immediately and get back to Colombo. I immediately asked the Settlement Dept. employees to break camp and arrange to get back to Colombo. I left Dambagalla around 5 pm. I knew my wife would be anxious about my safety, as Colombo would have received the news of the Wellawaya attack much earlier in the day, but telephone facilities being available only in Post Offices at the time, there was no way of contacting her. I therefore thought of heading straight to Colombo, which I thought was the best course of action available to me in the rather exasperating circumstances I found myself in.

area was infested by JVP types, advised me to leave immediately and get back to Colombo. I immediately asked the Settlement Dept. employees to break camp and arrange to get back to Colombo. I left Dambagalla around 5 pm. I knew my wife would be anxious about my safety, as Colombo would have received the news of the Wellawaya attack much earlier in the day, but telephone facilities being available only in Post Offices at the time, there was no way of contacting her. I therefore thought of heading straight to Colombo, which I thought was the best course of action available to me in the rather exasperating circumstances I found myself in.

I therefore packed up hurriedly and left immediately in my car driving alone, as the others expressed their preference to stay back and leave the next day. On the way, there were hardly any visible signs of any impending insurrection. I noticed however, that vehicular traffic on the road was much less, which made it easier for me drive at higher than normal speeds. It was only while approaching Ratnapura that I noticed a couple of trucks going ahead of me filled with what appeared to me albizzia leaves. As I was overtaking them, I was surprised to see that the trucks were filled with young chaps trying to camouflage themselves with leaves!

Again a little beyond Avissawella, with the time being around 10 pm, I noticed about four people on the middle of the road trying to wave me down and stop me. I noticed that there was one tree trunk placed across the road a little beyond where the four persons were and instinctively felt that I could just manage to take my Triumph Herald through the gap left on the road. I therefore revved the engine and drove straight at the four chaps who shouted and jumped onto a side to save themselves from being run over. The gap on the road was, as I expected, just wide enough to let my car through. Strangely, I was not unduly frightened due, perhaps to the exuberance of youth! I managed to reach Colombo around 11 pm much to the surprise and relief of my wife and others. They had been trying desperately to contact me to tell me to stay on in Moneragala without hazarding the journey back to Colombo in the night.

I thanked my stars that I had left for Colombo without thinking of the risks involved in traveling in the night, as the next day, all hell broke loose, with Police Stations island- wide coming under attack by the JVP! Readers will remember the horrors unleashed by the JVP in the weeks that followed and also the ruthless measures the Govt. had to recourse to thereafter , in its efforts to quell the insurgency and restore normalcy.

My Second spell in the Housing Dept. as Deputy Commissioner of Housing

I was forced to take up duties in my old Dept. as Deputy Commissioner, by my good friend Sarath Amunugama, who happened to be Director, Combined Services at the time. I did learn a lot working in the above Govt. Depts. I had initially worked in.

My second spell in the Housing Dept. as Deputy Commissioner, which commenced in 1973 and continued uptil 1978,was less stressful for me, despite the enactment of two new laws viz. The Rent Act and the Ceiling on Housing Property Law, which were looked upon by landlords as draconian legislative measures regulating rentals and house ownership. These laws gave much needed relief to tenants by regulating their monthly rentals and by providing security of tenancy. House owners who possessed houses in excess of the ceiling laid down, had to dispose of such excess houses to the tenants at relatively low prices.

These were laws enacted by a Govt. with a strong socialist bent and had far reaching effects by the relief they afforded tenants. The Ceiling on Housing Property Law however acted as a disincentive to investment in housing until amendments were later brought in, to encourage prospective developers to get into the construction industry by building middle and lower middle income houses for which certain tax concessions and financial incentives were extended.

As Deputy Commissioner. I was put in charge of the Administration Division of the Dept. and was also given the management of Flats and Housing schemes in the City. With Mr. Pieter Keuneman becoming the Minister of Housing, managing the minor employees who, without exception, claimed to be Communists, posed a big challenge. However, Mr. Keuneman, the thorough gentleman he was, did not intercede on behalf of employees who had disciplinary problems and for the most part left decisions on such matters, in my hands. I handled things even handedly, which is the best way to deal with difficult people and in difficult situations.

From the beginning of my public service career, the one principle I followed scrupulously in interacting with employees as well as members of the public, was being open and fair and being free of prejudice. Once people realized that I was only carrying out my duty with no personal stake or interest in what I did, they learnt to accept even the unfavourable decisions taken against them without bitterness or personal rancour.

When I acted as Commissioner of Housing, the Secretary to the Ministry at the time tried to badger me to transfer a house in a prime locality in Colombo to the tenant, under the Ceiling on Housing Property Law, at the behest of a powerful Minister. I stood my ground and refused to do so as such a transfer was irregular under the relevant legal provisions. He even fixed up a consultation in the chambers of a leading lawyer who is now deceased, who in turn tried to persuade me that it was in order to effect the transfer. I refused to budge from the position I had taken up, despite the consultation going on till late in the night. I refused to yield to all the cajoling and the entreaties as I was convinced in my own mind that any such action on my part would have been irregular and untenable. It does pay not to give in to pressure where you are convinced that you would not be able to justify your actions in such instances.

In May 1977 I was selected to attend a seminar on “Access to Housing” at the Institute of Development Studies, Sussex, UK. As I was handling the administration of flats and housing schemes in the city and it’s suburbs, there were innumerable problems which I had to inquire into, concerning disputes between neighbouring tenants which were often unimaginably petty. Curiously, I discovered that the higher one’s station in life, such disputes seemed to assume intensely acrimonious proportions. In extreme cases, the more stubborn tenants were threatened by me with a transfer to the ‘L’ Block (called the Hell Block) in the Bambalapitiya flats which often did the trick!

There was at this time a lot of agitation by tenants to have their flats and houses converted from monthly rental to rent purchase. The genial Communist Minister at the time, Mr.Pieter Keuneman, appointed a Committee comprising myself, Dr. Michael Joachim another Deputy Commissioner and the Chief Accountant Mr. Thurairajah, to recommend an appropriate basis to effect such a conversion. The Committee examined the problem in depth and recommended a fair and equitable basis for such a conversion which the Minister had no hesitation in recommending to Cabinet. This was a far reaching measure which laid the basis for tenants selected for Govt. flats and houses thereafter, to be given such premises on a rent purchase basis.

I remember distinctly the jubilation of the tenants in Bambalapitiya and other schemes when the new measures were announced. The Committee took into account the period of occupation by the tenants concerned in determining the down payment required to be made by them. This meant that rather than being tenants in perpetuity, they could come to own the flats/houses at the end of a given period. The guidelines laid down by the Committee were followed thereafter by the Housing Dept. in the allocation of Govt. flats and Houses to tenants on a rent –purchase basis. The Committee found the assignment most satisfying as it revolutionized the basis of allocation of Govt. houses to tenants by ensuring security of tenancy and the eventual ownership by tenants.

In 1978, I proceeded to Canberra, Australia on a scholarship to do my Post Graduate Diploma in Public Administration at the Canberra College of Advanced Education now renamed the University of Curtin. I found my course, over a period of one year, most rewarding as I had the fortune of studying under lecturers who were reputed internationally for the outstanding contributions made by them in their particular specialities.

On my return to the island my good friend Dunstan Jayawardena, was insisting that I work in the newly established National Housing Development Authority which had taken over most of the functions performed earlier by the Housing Dept. I enjoyed my short stint in the Housing Authority as Dunstan gave me a free hand in the work I handled .This was a time of frenzied activity under Mr. R. Premadasa who was the Minister of Housing and Construction under the new UNP dispensation. It was here that I first had a foretaste of the commitment and unremitting drive of Mr. Premadasa to help the countless lower middle class and the impoverished people, who were living in hovels and shanties, particularly in the cities and the suburbs, to move into newly built flats which were allocated to them on a rent purchase basis.

It was indeed the dawn of a new era for the thousands of shanty dwellers living in sub-standard houses to move into these new flats in the city and into decent permanent houses in the rural areas under the Gam Udawa and the rural housing programmes, he launched island wide.

I feel, I must say something about one of the most colourful and endearing personalities I have encountered in my career in the Public Service – Susil Siriwardhana. Susil was born with the proverbial ‘silver spoon and had done the traditional familial trek to Oxford University where he had majored in the English Language. On his return to SL, brimming with enthusiasm and fired with socialist ideals, he may have perhaps thought of working at grass-roots level to acquaint himself first hand with things at the village level, when he decided to teach in a school in Anuradhapura. I first met him in Kandy in the company of a mutual friend- Rama Somasundaram. Susil ran an elegant flat in Kandy where we used to meet and sit on cushions to discuss matters ranging from poetry to what was happening in the local political scene, over coffee served by a faithful retainer. I was then working as Asst. Commissioner /Housing attached to the Kandy Branch Office, while Rama functioned as Land Development Officer. This is where our friendship started.

Soon afterwards, Susil sat the Ceylon Administrative Service Examination acquitting himself brilliantly by scoring heavily in both the written test as well as the Viva Voce and coming first in the examination. After my transfer to the Dept. of Agrarian Services, I virtually lost track of Susil, except for a few accidental encounters on the corridors of the Treasury,where Susil used to tell me with a lot of passion, ‘Chandra, there is so much to be done’. I never realized for a moment, what Susil wanted to convey to me in that brief sentence, which presumably left so much unsaid.

The next thing I heard about Susil was that he had been taken into custody for his alleged involvement in the JVP insurrection of 1971. This shocked me and many others who knew Susil as a deeply committed young man, thoroughly involved with his official duties.

Susil was incarcerated and charged in Court for the support he had lent the JVP insurrection. Justice Alles who was one of the Presiding Judges hearing the cases against the accused insurgents, subsequently wrote a book on the Insurrection where he devoted one full chapter to Susil. Justice Alles may perhaps have been intrigued no end, how a cultured person like Susil, with his fine family background, could possibly have been in cahoots with characters like Wijeweera, Gamanayaka and their likes!

Minister of Housing Mr.Premadasa’s infatuation with Susil

Minister Premadasa perhaps saw in Susil a person who would bring commitment and creativity to whatever work was entrusted to him and further saw in him a veritable asset to him in the implementation of his pet housing programmes. Soon after his release from prison, Susil was appointed as a Deputy General Manager in the National Housing Authority by Mr. Premadasa . I remember Susil coming to work in national dress, on his Vespa scooter and going up to his office carrying his trademark ‘pang malla’, in his hand. We became close friends once again.

I remember once, while waiting at Ratmalana Airport to take a flight to a Gam Udawa Exhibition, I struck up a conversation with Susil in the course of which, I asked him pointedly what had really made him join the JVP. I remember clearly how he looked at me intently with his piercing eyes saying “The five lessons Chandra, the five lessons. It was like swallowing narcotic pills”! I must say Mr. Premadasa made the maximum use of Susil in getting him to join him in taking forward his pet housing programmes. Susil too did not let the Minister down and worked for him with a high sense of commitment.

I also recall a rather amusing episode where Susil sat with me on an Interview Board to recruit about ten engineers to the Authority. The candidates who came before us, numbering about 25, were young qualified engineers. I remember Susil’s enthusiasm when it came to some of the candidates – ‘Chandra, this chap is excellent material. We will take him’. Much later, I discovered that of the 10 engineers we had selected, the majority were ex JVP members! However, I must say that they turned out to be very good engineers who were very enthusiastic about their official assignments. They were naturally somewhat reticent in opening out and talking about their past ‘adventures’ as JVP cadres. There was one electrical engineer however, who was a bit more forthcoming than his colleagues and spoke to me about a near brush he had had with death when he and some detainees had been taken by the Police to be shot in Uduwattakele, Kandy. For his luck he had been recognized by a young ASP by the name of Shanmugam and through the latter’s intervention, had been spared the summary punishment meted out to the others.

All these engineers were an affable and competent lot and many of them obtained their post – graduate qualifications, some even becoming academics, securing senior University positions both here and abroad. As for Susil, he sobered down to the point where his colleagues and friends found it difficult to believe that he could have had anything to do with the 1971 insurgency. I suppose it was his idealism and youthful exuberance that led to his association with the revolutionary types. Susil, soon afterwards, entered wedlock and settled down to an exemplary family life.

Features

Digital transformation in the Global South

Understanding Sri Lanka through the India AI Impact Summit 2026

Artificial Intelligence (AI) has rapidly moved from being a specialised technological field into a major social force that shapes economies, cultures, governance, and everyday human life. The India AI Impact Summit 2026, held in New Delhi, symbolised a significant moment for the Global South, especially South Asia, because it demonstrated that artificial intelligence is no longer limited to advanced Western economies but can also become a development tool for emerging societies. The summit gathered governments, researchers, technology companies, and international organisations to discuss how AI can support social welfare, public services, and economic growth. Its central message was that artificial intelligence should be human centred and socially useful. Instead of focusing only on powerful computing systems, the summit emphasised affordable technologies, open collaboration, and ethical responsibility so that ordinary citizens can benefit from digital transformation. For South Asia, where large populations live in rural areas and resources are unevenly distributed, this idea is particularly important.

People friendly AI

One of the most important concepts promoted at the summit was the idea of “people friendly AI.” This means that artificial intelligence should be accessible, understandable, and helpful in daily activities. In South Asia, language diversity and economic inequality often prevent people from using advanced technology. Therefore, systems designed for local languages, and smartphones, play a crucial role. When a farmer can speak to a digital assistant in Sinhala, Tamil, or Hindi and receive advice about weather patterns or crop diseases, technology becomes practical rather than distant. Similarly, voice based interfaces allow elderly people and individuals with limited literacy to use digital services. Affordable mobile based AI tools reduce the digital divide between urban and rural populations. As a result, artificial intelligence stops being an elite instrument and becomes a social assistant that supports ordinary life.

Transformation in education sector

The influence of this transformation is visible in education. AI based learning platforms can analyse student performance and provide personalised lessons. Instead of all students following the same pace, weaker learners receive additional practice while advanced learners explore deeper material. Teachers are able to focus on mentoring and explanation rather than repetitive instruction. In many South Asian societies, including Sri Lanka, education has long depended on memorisation and private tuition classes. AI tutoring systems could reduce educational inequality by giving rural students access to learning resources, similar to those available in cities. A student who struggles with mathematics, for example, can practice step by step exercises automatically generated according to individual mistakes. This reduces pressure, improves confidence, and gradually changes the educational culture from rote learning toward understanding and problem solving.

Healthcare is another area where AI is becoming people friendly. Many rural communities face shortages of doctors and medical facilities. AI-assisted diagnostic tools can analyse symptoms, or medical images, and provide early warnings about diseases. Patients can receive preliminary advice through mobile applications, which helps them decide whether hospital visits are necessary. This reduces overcrowding in hospitals and saves travel costs. Public health authorities can also analyse large datasets to monitor disease outbreaks and allocate resources efficiently. In this way, artificial intelligence supports not only individual patients but also the entire health system.

Agriculture, which remains a primary livelihood for millions in South Asia, is also undergoing transformation. Farmers traditionally rely on seasonal experience, but climate change has made weather patterns unpredictable. AI systems that analyse rainfall data, soil conditions, and satellite images can predict crop performance and recommend irrigation schedules. Early detection of plant diseases prevents large-scale crop losses. For a small farmer, accurate information can mean the difference between profit and debt. Thus, AI directly influences economic stability at the household level.

Employment and communication reshaped

Artificial intelligence is also reshaping employment and communication. Routine clerical and repetitive tasks are increasingly automated, while demand grows for digital skills, such as data management, programming, and online services. Many young people in South Asia are beginning to participate in remote work, freelancing, and digital entrepreneurship. AI translation tools allow communication across languages, enabling businesses to reach international customers. Knowledge becomes more accessible because information can be summarised, translated, and explained instantly. This leads to a broader sociological shift: authority moves from tradition and hierarchy toward information and analytical reasoning. Individuals rely more on data when making decisions about education, finance, and career planning.

Impact on Sri Lanka

The impact on Sri Lanka is especially significant because the country shares many social and economic conditions with India and often adopts regional technological innovations. Sri Lanka has already begun integrating artificial intelligence into education, agriculture, and public administration. In schools and universities, AI learning tools may reduce the heavy dependence on private tuition and help students in rural districts receive equal academic support. In agriculture, predictive analytics can help farmers manage climate variability, improving productivity and food security. In public administration, digital systems can speed up document processing, licensing, and public service delivery. Smart transportation systems may reduce congestion in urban areas, saving time and fuel.

Economic opportunities are also expanding. Sri Lanka’s service based economy and IT outsourcing sector can benefit from increased global demand for digital skills. AI-assisted software development, data annotation, and online service platforms can create new employment pathways, especially for educated youth. Small and medium entrepreneurs can use AI tools to design products, manage finances, and market services internationally at low cost. In tourism, personalised digital assistants and recommendation systems can improve visitor experiences and help small businesses connect with travellers directly.

Digital inequality

However, the integration of artificial intelligence also raises serious concerns. Digital inequality may widen if only educated urban populations gain access to technological skills. Some routine jobs may disappear, requiring workers to retrain. There are also risks of misinformation, surveillance, and misuse of personal data. Ethical regulation and transparency are, therefore, essential. Governments must develop policies that protect privacy, ensure accountability, and encourage responsible innovation. Public awareness and digital literacy programmes are necessary so that citizens understand both the benefits and limitations of AI systems.

Beyond economics and services, AI is gradually influencing social relationships and cultural patterns. South Asian societies have traditionally relied on hierarchy and personal authority, but data-driven decision making changes this structure. Agricultural planning may depend on predictive models rather than ancestral practice, and educational evaluation may rely on learning analytics instead of examination rankings alone. This does not eliminate human judgment, but it alters its basis. Societies increasingly value analytical thinking, creativity, and adaptability. Educational systems must, therefore, move beyond memorisation toward critical thinking and interdisciplinary learning.

AI contribution to national development

In Sri Lanka, these changes may contribute to national development if implemented carefully. AI-supported financial monitoring can improve transparency and reduce corruption. Smart infrastructure systems can help manage transportation and urban planning. Communication technologies can support interaction among Sinhala, Tamil, and English speakers, promoting social inclusion in a multilingual society. Assistive technologies can improve accessibility for persons with disabilities, enabling broader participation in education and employment. These developments show that artificial intelligence is not merely a technological innovation but a social instrument capable of strengthening equality when guided by ethical policy.

Symbolic shift

Ultimately, the India AI Impact Summit 2026 represents a symbolic shift in the global technological landscape. It indicates that developing nations are beginning to shape the future of artificial intelligence according to their own social needs rather than passively importing technology. For South Asia and Sri Lanka, the challenge is not whether AI will arrive but how it will be used. If education systems prepare citizens, if governments establish responsible regulations, and if access remains inclusive, AI can become a partner in development rather than a source of inequality. The future will likely involve close collaboration between humans and intelligent systems, where machines assist decision making while human values guide outcomes. In this sense, artificial intelligence does not replace human society, but transforms it, offering Sri Lanka an opportunity to build a more knowledge based, efficient, and equitable social order in the decades ahead.

by Milinda Mayadunna

Features

Governance cannot be a postscript to economics

The visit by IMF Managing Director Kristalina Georgieva to Sri Lanka was widely described as a success for the government. She was fulsome in her praise of the country and its developmental potential. The grounds for this success and collaborative spirit go back to the inception of the agreement signed in March 2023 in the aftermath of Sri Lanka’s declaration of international bankruptcy. The IMF came in to fulfil its role as lender of last resort. The government of the day bit the bullet. It imposed unpopular policies on the people, most notably significant tax increases. At a moment when the country had run out of foreign exchange, defaulted on its debt, and faced shortages of fuel, medicine and food, the IMF programme restored a measure of confidence both within the country and internationally.

Since 1965 Sri Lanka has entered into agreements with the IMF on 16 occasions none of which were taken to their full term. The present agreement is the 17th agreement . IMF agreements have traditionally been focused on economic restructuring. Invariably the terms of agreement have been harsh on the people, with priority being given to ensure the debtor country pays its loans back to the IMF. Fiscal consolidation, tax increases, subsidy reductions and structural reforms have been the recurring features. The social and political costs have often been high. Governments have lost popularity and sometimes fallen before programmes were completed. The IMF has learned from experience across the world that macroeconomic reform without social protection can generate backlash, instability and policy reversals.

The experience of countries such as Greece, Ireland and Portugal in dealing with the IMF during the eurozone crisis demonstrated the political and social costs of austerity, even though those economies later stabilised and returned to growth. The evolution of IMF policies has ensured that there are two special features in the present agreement. The first is that the IMF has included a safety net of social welfare spending to mitigate the impact of the austerity measures on the poorest sections of the population. No country can hope to grow at 7 or 8 percent per annum when a third of its people are struggling to survive. Poverty alleviation measures in the Aswesuma programme, developed with the agreement of the IMF, are key to mitigating the worst impacts of the rising cost of living and limited opportunities for employment.

Governance Included

The second important feature of the IMF agreement is the inclusion of governance criteria to be implemented alongside the economic reforms. It goes to the heart of why Sri Lanka has had to return to the IMF repeatedly. Economic mismanagement did not take place in a vacuum. It was enabled by weak institutions, politicised decision making, non-transparent procurement, and the erosion of checks and balances. In its economic reform process, the IMF has included an assessment of governance related issues to accompany the economic restructuring process. At the top of this list is tackling the problem of corruption by means of publicising contracts, ensuring open solicitation of tenders, and strengthening financial accountability mechanisms.

The IMF also encouraged a civil society diagnostic study and engaged with civil society organisations regularly. The civil society analysis of governance issues which was promoted by Verite Research and facilitated by Transparency International was wider in scope than those identified in the IMF’s own diagnostic. It pointed to systemic weaknesses that go beyond narrow fiscal concerns. The civil society diagnostic study included issues of social justice such as the inequitable impact of targeting EPF and ETF funds of workers for restructuring and the need to repeal abuse prone laws such as the Prevention of Terrorism Act and the Online Safety Act. When workers see their retirement savings restructured without adequate consultation, confidence in policy making erodes. When laws are perceived to be instruments of arbitrary power, social cohesion weakens.

During a meeting between the IMF Managing Director Georgeiva and civil society members last week, there was discussion on the implementation of those governance measures in which she spoke in a manner that was not alien to the civil society representatives. Significantly, the civil society diagnostic report also referred to the ethnic conflict and the breakdown of interethnic relations that led to three decades of deadly war, causing severe economic losses to the country. This was also discussed at the meeting. Governance is not only about accounting standards and procurement rules. It is about social justice, equality before the law, and political representation. On this issue the government has more to do. Ethnic and religious minorities find themselves inadequately represented in high level government committees. The provincial council system that ensured ethnic and minority representation at the provincial level continues to be in abeyance.

Beyond IMF

The significance of addressing governance issues is not only relevant to the IMF agreement. It is also important in accessing tariff concessions from the European Union. The GSP Plus tariff concession given by the EU enables Sri Lankan exports to be sold at lower prices and win markets in Europe. For an export dependent economy, this is critical. Loss of such concessions would directly affect employment in key sectors such as apparel. The government needs to address longstanding EU concerns about the protection of human rights and labour rights in the country. The EU has, for several years, linked the continuation of GSP Plus to compliance with international conventions. This includes the condition that the Prevention of Terrorism Act (PTA) be brought into line with international standards. The government’s alternative in the form of the draft Protection of the State from Terrorism Act (PTSA) is less abusive on paper but is wider in scope and retains the core features of the PTA.

Governance and social justice factors cannot be ignored or downplayed in the pursuit of economic development. If Sri Lanka is to break out of its cycle of crisis and bailout, it must internalise the fact that good governance which promotes social justice and more fairly distributes the costs and fruits of development is the foundation on which durable economic growth is built. Without it, stabilisation will remain fragile, poverty will remain high, and the promise of 7 to 8 percent growth will remain elusive. The implementation of governance reforms will also have a positive effect through the creative mechanism of governance linked bonds, an innovation of the present IMF agreement.

The Sri Lankan think tank Verité Research played an important role in the development of governance linked bonds. They reduce the rate of interest payable by the government on outstanding debt on the basis that better governance leads to a reduction in risk for those who have lent their money to Sri Lanka. This is a direct financial reward for governance reform. The present IMF programme offers an opportunity not only to stabilise the economy but to strengthen the institutions that underpin it. That opportunity needs to be taken. Without it, the country cannot attract investment, expand exports and move towards shared prosperity and to a 7-8 percent growth rate that can lift the country out of its debt trap.

by Jehan Perera

Features

MISTER Band … in the spotlight

It’s a good sign, indeed, for the local scene, to see artistes, who have not been very much in the limelight, now making their presence felt, in a big way, and I’m glad to give them the publicity they deserve.

It’s a good sign, indeed, for the local scene, to see artistes, who have not been very much in the limelight, now making their presence felt, in a big way, and I’m glad to give them the publicity they deserve.

On 10th February we had Yellow Beatz in the spotlight and this week it’s MISTER Band.

This outfit is certainly not new to our scene; they have been around since 2012, under the leadership of Sithum Waidyarathne.

The seven energetic members who make up MISTER Band are:

Sithum Waidyarathne (leader/founder/saxophonist/guitarist and vocalist), Rangana Seram (bass guitarist), Vihanga Liyanage (vocalist), Ridmi Dissanayake (female vocalist), Nuwan Cristo (keyboardist/vocalist), Kasun Thennakoon (lead guitarist), and Nuwan Madushanka (drummer).

According to Sithum, their vision is to provide high quality entertainmen to those who engage their services.

“Thanks to our engaging performances and growing popularity, MISTER Band continues to be in high demand … at weddings, corporate events and dinner dances,” said Sithum.

They predominantly cover English and Sinhala music, as well as the most popular genres.

And the reviews that come their way, after a performance, are excellent, they say, and this is one of the bouquets they received:

It was a pleasure to have you at our wedding. Being avid music fans we wanted the best music, not just a big named band, and you guys acceded that expectations. Big thanks to Sithum for being very supportive, attentive and generous.

- Sithum Waidyarathne: Band leader and founder

- Ridmi Dissanayake: MISTER Band’s female vocalist

The best thing is the post feedback from all the guests. Normally we get mixed reviews but the whole crowd was impressed by you.

MISTER Band was one of our best choices for our wedding.

What is interesting is that for the past four consecutive years, this outfit has performed overseas, during New Year’s Eve, thereby taking their music to the international stage, as well.

The band has also produced a collection of original songs, with around six original tracks composed by the band leader, Sithum Waidyarathne, including ‘Suraganak Dutuwa,’ ‘Landuni,’ ‘Dili Dili Payana,’ ‘Hada Wedana,’ and ‘Nil Kandu Athare.’

Two more songs are set to be released this month: ‘Hitha Norida’ and ‘Premaye Hanguman.’

In addition to their original music, they have also created a strong online presence by performing and uploading over 50 cover songs and medleys to YouTube.

“We’re now planning to connect with an even wider audience by releasing more cover content very soon,” said Sithum, adding that they are also very active on social media, under the name Mister Band Official – on Facebook, Instagram, YouTube, and TikTok.

-

Features3 days ago

Features3 days agoWhy does the state threaten Its people with yet another anti-terror law?

-

Features3 days ago

Features3 days agoVictor Melder turns 90: Railwayman and bibliophile extraordinary

-

Features3 days ago

Features3 days agoReconciliation, Mood of the Nation and the NPP Government

-

Features2 days ago

Features2 days agoLOVEABLE BUT LETHAL: When four-legged stars remind us of a silent killer

-

Features3 days ago

Features3 days agoVictor, the Friend of the Foreign Press

-

Latest News4 days ago

Latest News4 days agoNew Zealand meet familiar opponents Pakistan at spin-friendly Premadasa

-

Latest News4 days ago

Latest News4 days agoTariffs ruling is major blow to Trump’s second-term agenda

-

Latest News4 days ago

Latest News4 days agoECB push back at Pakistan ‘shadow-ban’ reports ahead of Hundred auction