Foreign News

Namibia’s president Hage Geingob dies aged 82

Namibia’s President Hage Geingob has died at the age of 82 while receiving medical treatment at a hospital in the capital, Windhoek.

A veteran of the country’s independence struggle, Geingob had been diagnosed with cancer and revealed the details to the public last month. He died early on Sunday with his wife and children by his side, Vice-President Nangolo Mbumba announced.

Mr Mbumba has since been sworn-in as his replacement. He will serve in the role until elections are held later this year.

“I take on this heavy mantle cognisant of the weight of responsibility,” Mr Mbumba said at a swiftly arranged swearing-in ceremony at state house in Windhoek, just 15 hours after the death of Mr Geingob. Paying tribute to his predecessor, he said that “our nation remains calm and stable owing to the leadership of President Geingob who was the chief architect of the constitution”.

Mr Geingob was first sworn-in as president in 2015, but had served in top political positions since independence in 1990.

The exact cause of his death was not given but last month he underwent “a two-day novel treatment for cancerous cells” in the US before flying back home on 31 January, his office has said.

On Namibian radio, people have been sharing memories of someone they described as a visionary as well as a jovial man, who was able to share a joke.

Leaders from around the world have been sending condolence messages with many talking about Mr Geingob’s efforts to ensure his country’s freedom.

Among them has been Cyril Ramaphosa, president of neighbouring South Africa, who described him as “a towering veteran of Namibia’s liberation from colonialism and apartheid”.

Mr Geingob, a tall man with a deep, gravelly voice and a commanding presence was a long-serving member of the Swapo party. It led the movement against apartheid South Africa, which had effectively annexed the country, then known as South West Africa, and introduced its system of legalised racism that excluded black people from political and economic power.

Mr Geingob lived in exile for 27 years, spending time in Botswana, the US and the UK, where he studied for a PhD in politics. He came back to Namibia in 1989, a year before the country gained independence.

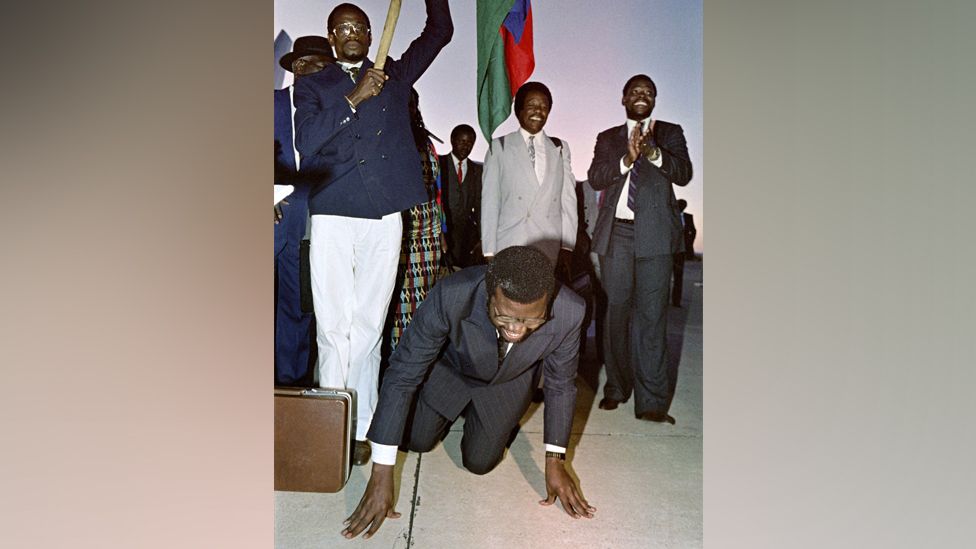

“Looking back, the journey of building a new Namibia has been worthwhile,” he wrote on social media in 2020 while sharing a picture of him kissing the ground on his return.

“Even though we have made a lot of progress in developing our country, more work lies ahead to build an inclusive society.”

When Mr Geingob first became president in 2015, he had already been the country’s longest-serving prime minister – in the post for 12 years from 1990 and then again for a shorter stint in 2012.

But going by results at the ballot box, his popularity had declined. In the 2014 election, he won a huge majority, taking 87% of the vote. But five years later that had fallen to 56%.

Mr Geingob’s first term coincided with a stagnant economy and high levels of unemployment and poverty, according to the World Bank.

His party also faced a number of corruption scandals during his time in office. This included what became known as “fishrot”, where ministers and top officials were accused of taking bribes in exchange for the awarding of lucrative fishing quotas.

By 2021, three-quarters of the population thought that the country was going in the wrong direction, a three-fold increase since 2014, according to independent polling organisation Afrobarometer.

Three decades after independence, the heroic narrative of Swapo having liberated the country was losing its appeal among a generation born after the event, long-time observer of Namibian politics Henning Melber wrote in 2021.

Swapo, in power since independence, had chosen Netumbo Nandi-Ndaitwah as its presidential candidate for November’s planned elections. She has now been appointed vice-president and will become the country’s first female president if she wins.

(BBC)

Foreign News

From behind bars, Aung San Suu Kyi casts a long shadow over Myanmar

As of Wednesday the Burmese democracy campaigner Aung San Suu Kyi will have spent a total of 20 years in detention in Myanmar, five of them since her government was overthrown by a military coup in February 2021.

Almost nothing is known about her state of health, or the conditions she is living in, although she is presumed to be held in a military prison in the capital Nay Pyi Taw. “For all I know she could be dead,” her son Kim Aris said last month, although a spokesman for the ruling military junta insisted she is in good health.

She has not seen her lawyers for at least two years, nor is she known to have seen anyone else except prison personnel. After the coup she was given jail sentences totaling 27 years on what are widely viewed as fabricated charges.

Yet despite her disappearance from public view, she still casts a long shadow over Myanmar.

There are repeated calls for her release, along with appeals to the generals to end their ruinous campaign against the armed opposition and negotiate an end to the civil war that has now dragged on for five years.

The military has tried to remove her once ubiquitous image, but you still see faded posters of “The Lady”, or “Amay Su”, Mother Su, as she is affectionately known, in tucked away corners. Could she still play a role in settling the conflict between the soldiers and the people of Myanmar?

After all, it has happened before. Back in 2010 the military had been in power for nearly 50 years, brutally crushed all opposition and run the economy into the ground. Just as it is doing now, it organised a general election which excluded Aung San Suu Kyi’s popular National League for Democracy, and which it ensured its own proxy party, the USDP, would win.

As with this election, which is still underway in phases, the one in 2010 was dismissed by most countries as a sham. Yet at the end of that year Aung San Suu Kyi was released, and within 18 months she had been elected an MP. By 2015 her party had won the first free election since 1960, and she was de facto leader of the country.

To the outside world it seemed an almost miraculous democratic transition, evidence perhaps that among the stony-faced generals there might be genuine reformers.

So could we see a re-run of that scenario once the junta has completed its three-stage election at the end of this month?

A lot has changed between then and now.

Back then there had been many years of engagement between the generals and an assortment of UN envoys, exploring ways to end their pariah status and re-engage with the rest of the world. It was a more optimistic era; the generals could see their South East Asian neighbours prospering through trade with the Western world, and they wanted an end to crippling economic sanctions.

They also sought better relations with the US as a counterbalance to their dependence on China, at a time when the Obama administration was making its celebrated “pivot” to Asia.

The top generals were still hard-line and suspicious, but there was a group of less senior officers keen to explore a political compromise.

It is not clear what finally persuaded the military leadership to open the country up, but they clearly believed their 2008 constitution, which guaranteed the armed forces one-quarter of the seats in a future parliament, would be enough, with their well-funded party, to limit Aung San Suu Kyi’s influence once she was released.

They badly underestimated her massive star power, and they underestimated how much their decades of misrule had alienated most of the population.

In the 2015 election the USDP won just over 6% of the seats in both houses of parliament. In the next election in 2020 it expected to perform much better, after five years of an NLD administration which had started with impossibly high hopes, and had inevitably disappointed many of them. But the USDP fared even worse, winning just 5% of seats in the two houses.

Even many of those who were dissatisfied with Aung San Suu Kyi’s performance in government still chose hers over the military’s party. This raised the possibility that she might eventually win enough support to change the constitution, and end the military’s privileged position.

It also ruled out the armed forces commander Min Aung Hlaing’s hopes of becoming president after his retirement. He launched his coup on 1 February 2021, the day Aung San Suu Kyi was due to inaugurate her new government.

This time there are no reformers in the ranks, and no hopes of the kind of compromise which restored democracy back in 2010. The shocking violence used to put down protests against the coup has driven many young Burmese to take up arms against the junta. Tens of thousands have been killed, tens of thousands of homes have been destroyed. Attitudes on both sides have hardened.

The 15 years Aung San Suu Kyi was detained after 1989, under conditions of house arrest in her lakeside family home in Yangon, were very different from the conditions she is being held in today. Her dignified, non-violent resistance won her admirers across Myanmar and around the world, and during the occasional spells of freedom the military gave her she was able to give rousing speeches from her front gate, or interviews to journalists.

Today she is invisible. Her long-held belief in non-violent struggle has been rejected by those who have joined the armed resistance, who argue that they must fight to end the military’s role in Myanmar’s political life. There is a lot more criticism of how Aung San Suu Kyi governed when she was in power than before.

Her decision to lead Myanmar’s defence against charges of genocide at the International Court of Justice over the military’s atrocities against Muslim Rohingyas in 2017 badly tarnished her saint-like international image. It had much less resonance inside Myanmar, but many younger opposition activists are now willing to condemn how she handled the Rohingya crisis.

At the age of 80, with uncertain health, it is not clear how much influence she would have, were she to be released, even if she still wants to play a central role.

And yet her long struggle against military rule made her synonymous with all the hopes of a freer, more democratic future.

There is simply no-one else of her stature in Myanmar, and for that reason alone, many would argue, she is probably still needed if the country is to chart a path out of its current deadlock.

[BBC]

Foreign News

Meta blocks 550,000 accounts under Australia’s social media ban

About 550,000 accounts were blocked by Meta during the first days of Australia’s landmark social media ban for kids.

In December, a new law began requiring that the world’s most popular social media sites – including Instagram and Facebook – stop Australians aged under 16 from having accounts on their platforms.

The ban, which is being watched closely around the world, was justified by campaigners and the government as necessary to protect children from harmful content and algorithms.

Companies including Meta have said they agree more is needed to keep young people safe online. However they continue to argue for other measures, with some experts raising similar concerns.

“We call on the Australian government to engage with industry constructively to find a better way forward, such as incentivising all of industry to raise the standard in providing safe, privacy-preserving, age appropriate experiences online, instead of blanket bans,” Meta said in a blog update.

The company said it blocked 330,639 accounts on Instagram, 173,497 on Facebook, and 39,916 on Threads during it’s first week of compliance with the new law.

They again put the argument that age verification should happen at an app store level – something they suggested lowers the burden of compliance on both regulators and the apps themselves – and that exemptions for parental approval should be created.

“This is the only way to guarantee consistent, industry-wide protections for young people, no matter which apps they use, and to avoid the whack-a-mole effect of catching up with new apps that teens will migrate to in order to circumvent the social media ban law.”

Various governments, from the US state of Florida to the European Union, have been experimenting with limiting children’s use of social media. But, along with a higher age limit of 16, Australia is the first jurisdiction to deny an exemption for parental approval in a policy like this – making its laws the world’s strictest.

The policy is wildly popular with parents and envied by world leader, with the Tories this week pledging to follow suit if they win power at the next election, due before 2029.

However some experts have raised concerns that Australian kids can circumvent the ban with relative ease – either by tricking the technology that’s performing the age checks, or by finding other, potentially less safe, places on the net to gather.

And backed by some mental health advocates, many children have argued it robs young people of connection – particularly those from LGBTQ+, neurodivergent or rural communities – and will leave them less equipped to tackle the realities of life on the web.

(BBC)

Foreign News

Bride and groom killed by gas explosion day after Pakistan wedding

A newly married couple were killed when a gas cylinder exploded at a house in Islamabad where they were sleeping after their wedding party, police have said.

A further six people – including wedding guests and family members – who were staying there also died in the blast. More than a dozen people were injured.

The explosion took place at 07:00 local time (02:00 GMT) on Sunday, causing the roof to collapse.

Parts of the walls were blown away, leaving piles of bricks, large concrete slabs and furniture strewn across the floor. Injured people were trapped under the rubble and had to be carried out on stretchers by rescue workers.

(BBC)

-

Business4 days ago

Business4 days agoDialog and UnionPay International Join Forces to Elevate Sri Lanka’s Digital Payment Landscape

-

News4 days ago

News4 days agoSajith: Ashoka Chakra replaces Dharmachakra in Buddhism textbook

-

Features4 days ago

Features4 days agoThe Paradox of Trump Power: Contested Authoritarian at Home, Uncontested Bully Abroad

-

Features4 days ago

Features4 days agoSubject:Whatever happened to (my) three million dollars?

-

News4 days ago

News4 days agoLevel I landslide early warnings issued to the Districts of Badulla, Kandy, Matale and Nuwara-Eliya extended

-

Business1 day ago

Business1 day agoNew policy framework for stock market deposits seen as a boon for companies

-

Opinion6 days ago

Opinion6 days agoThe minstrel monk and Rafiki, the old mandrill in The Lion King – II

-

News4 days ago

News4 days ago65 withdrawn cases re-filed by Govt, PM tells Parliament