Features

My time at Sussex University in the mid-1970s

“Culture is like jam; the less you have, the more you spread”

by Jayantha Perera

The Central Bank of Ceylon had stringent forex laws and regulations in the seventies. In 1975, it approved 18 sterling pounds for me to take to England as a student and recorded the amount in my passport. The postgraduate studentship from the Institute of Development Studies (IDS) of Sussex University paid my airfare, tuition fees, and living expenses.

I travelled to Karachi from Colombo on October 1. The connecting flight to London was delayed because the plane had engine troubles. I did not have money to make a call to IDS or ARTI about the delay. The plan was for someone from IDS to meet me at Falmer railway station (the nearest to the university) on October 2 in the afternoon.

Pakistan Airlines organised a city tour on the third day for the stranded travellers. I was amazed to see crowded public buses and thousands of pedestrians. At a bazaar, I bought a rosewood pipe and a small tobacco pouch for nine pounds. I visualised how professors at Peradeniya smoked their pipes at the senior common room. I wanted to be a mature, pipe-smoking Marxist scholar at Sussex, which was then known to be a hotbed of Socialists and Marxists.

On October 5, I landed at the Heathrow Airport, tired and disoriented. I remembered it was my father’s eighth death anniversary. I tried to imagine what he would have told me about England. For him, leaving home was a hazardous business. At least, initially, he would have opposed my going to England. He had set ideas of what was suitable for his four sons. He wanted me to study law. Once, I asked him jokingly whether it would be okay to marry after completing my first degree. He was shocked and said I had enough time to think about such matters and should study without “spoiling’ my mind. He blamed my mother for “corrupting” me.

There were several immigration officers on duty, and most of them looked like Indians or Pakistanis. The immigration officer wanted to know my sources of finance at Sussex. He read the studentship offer letter carefully and re-checked the UK visa on my passport. He politely told me to get a chest X-ray at the airport clinic.

At the customs, an officer wanted to know why I was visiting England. I told him about my postgraduate studies at Sussex. He inquired if I had any cooked food in my bag. When I told him I hadn’t, he smiled and said, “Usually, Asian students bring cooked fish, meat, and dried fruits.” I was hungry. I walked to a café and bought a ham sandwich and a glass of milk. (That was the first time I ate ham and drank cold milk from a carton.) I took a double-decker bus to Victoria Railway Station.

I reached London Central Bus Station at 3 pm. A uniformed bus conductor called a taxi and told the driver to drop me at the Victoria railway station. It was a very short ride. I asked the driver how much I owed him and showed him several coins. He carefully checked them, took a 50 pence coin, and said, “This is enough.”

The train to Brighton was an express train, and I could not believe a train could travel that fast. I saw a young woman pushing a trolley on the aisle. She served coffee, tea, and sandwiches. Passengers paid for the food they took from her. I wanted to buy a sandwich, but I did not because I had only a few pounds in my pocket. I needed that money to buy a train ticket from Brighton to Falmer.

The view from the train was breathtaking. I enjoyed the undulating landscape and the mild haze that enveloped distant low mountains and woods. They reminded me of the picturesque English villages I had seen in school English textbooks. Occasionally, I spotted sheep grazing in vast stretches of rolling land. Lines of old houses, narrow streets, and forests with glistening streams uplifted my spirit. I thought about my childhood and adolescence, especially my life after my father’s death. As the train rattled on, I found myself lost in a whirlwind of memories and emotions, each landscape outside the window triggering a new thought or feeling.

There was a connecting local train to Lewis from Brighton, and it reached Falmer railway station in about 20 minutes. When I got off the train, an elderly gentleman greeted me. He introduced himself as the station master. He took my suitcase and led me to a tiny room at the Station. I saw a jar of biscuits, a few slices of cake, a large flask, and two mugs on a small table. He wanted to know why I was late. I told him that the flight was delayed in Karachi. He offered me a slice of cake on a paper plate with a plastic fork and asked whether I wanted a cup of tea.

When I said, “Yes, please”, he asked me, “With or without sugar?” I said, “With sugar.” He pushed a container of white sugar cubes towards me. I asked him how many cubes to dissolve in the mug. He said two would be enough.

Then he said, “Oh, I am sorry. Would you like some milk with your tea?” I said, “Yes.” He opened a small packet of milk and poured a little into my tea mug, making tea lukewarm. I ate two slices of cake, and he then offered me a sizeable homemade chocolate biscuit from a jar in the room. He sat before me and said he was a young cadet at the Trincomalee Royal Air Force Base during World War II. He revisited Sri Lanka in the 1960s and stayed with his wife at the Galle Face Hotel for three nights before going to Trincomalee to see the Air Force base.

The station master accompanied me along the narrow path behind the Station to the Brighton-Lewis Highway. He advised me to cross the highway and read students’ graffiti on parapet walls. He waited until I crossed the road. I was thrilled to see the large graffiti on a parapet wall. One read –

‘Culture is like jam

the less you have,

the more you spread!’

I read the graffiti several times, stopping for a minute to absorb its meaning and context. It hinted that British culture was shallow. The British used force to deal with the people they met in the East or the West. China, which invented gunpowder, paper, the compass, and the printing press could have used such ‘weapons’ to conquer other people and build an empire, but they did not.

In five minutes, I reached the front entrance of the university. There was a Student Union kiosk. A student approached me, introduced himself, and welcomed me to the university. He offered me a cup of tea. I told him that I had just had tea at the railway station. Then, a man in a dark suit approached me and asked politely, “Are you Jayantha from Sri Lanka?” I smiled, and he introduced himself as Charlie and welcomed me to IDS. He was a porter at IDS. The stationmaster had phoned IDS to inform them of my arrival. Charlie opened a plastic bag, took out an old black overcoat, and asked me to wear it as it was getting cold. He carried my suitcase on his shoulder. We walked through the central court of the university. I could see the university’s motto – Be Still and Know – enshrined on the horizontal beam that connected two tall towers.

The IDS was a two-storied octagon-shaped building nestled in an undulating grassland that rose rapidly to form a thicket behind the university. Charlie introduced me to his colleagues and took me down to the cafeteria for a cup of tea. I ate a roll and drank a cup of hot chocolate. It reminded me of my mother, who gave me a hot cup of Ovaltine whenever I had a fever. Charlie paid the bill. He took me to the IDS Administrator’s office and told me to collect my suitcase from the porter’s office.

The Administrator was a charming man in his seventies with a disarming smile on his bearded face. He cordially hugged me for a minute or two and asked me, “How are you, son?” He told me he had spent a few weeks in Sri Lanka as a young army officer during the war. He opened a drawer, took out a brown envelope, and gave it to me, saying, “This is your stipend for the first term.” I felt happy and settled. He informed me I could stay at the IDS’ residential wing for two nights at the IDS’ expense. He invited me to dinner at the IDS cafeteria at 7 pm. I met Charlie downstairs, and he carried the suitcase to my suite.

The attached bathroom of the suite mesmerised me. It had a large bathtub and a beautiful wash basin with two taps. I opened one, and boiling water came gushing down; the other gave me ice-cold water. I plugged the washbasin drain and filled it with water from the two taps. I decided to drain water each time I rinse my mouth. I needed help with how to fill the bathtub or control the shower. I stepped out of the suite to get help and saw a tall old man with a beard at a fancy coffee machine in the corridor.

I asked him to show me how to operate the shower knobs to get hot water for a shower. He introduced himself as Dudley Seers, the former IDS director, and welcomed me to the IDS. I introduced myself and told him I had just arrived in the UK from Sri Lanka. He said that he was happy to meet me. He had many great memories of Sri Lanka, where, in the early 1970s, he led the ILO Employment and Development Mission. He remembered hot curries and aappa that he ate at roadside tea kiosks. He turned the knobs and showed me how to control cold and hot water.

I asked him how to operate the machine to get coffee. He inserted a coin, patiently played with several buttons, and produced a creamy coffee. It was different from the half glass of coffee my mother gave me, which had lots of sugar. He gave me two twenty-cent coins to get morning coffee from the machine.

Soon after I had a shower, there was a knock on the door. At the door was an old woman who introduced herself as the manager of the residential wing. She called me ‘my glamour,’ and I did not know how to respond. She smiled and told me she would return to take me down to dinner in an hour. Her sailor husband had visited Sri Lanka many times and once brought her a blue sapphire ring from Colombo.

I had a cold draft beer at the IDS bar, and it was like amurtha (nectar). I studied how the bartender siphoned beer into a large mug from a hidden barrel while debating with a customer on the British economy. The dinner was lavish. First, I had soup with bread and butter. This reminded me of issaraha kaema (a slice of bread served with a bowl of soup) at Sri Lankan weddings before lunch or dinner. I chose a steak covered with baked vegetables and fried onions. Then I had cheeses and crackers and, finally, a glass of Port.

The next day, I visited the Chairperson of the Sociology Department to introduce myself and to get the first term timetable. He sat behind a beautiful dark table. On it, there was a carved bamboo container with several pipes of different colours and shapes, neatly arranged according to their length. He asked me to sit down, picked a pipe, and fumbled with it without looking up. He then lighted his pipe and started smoking. His eyes got smaller, and I thought he was asleep, but he was awake. He welcomed me to the MA Sociology course and asked me about my preferred two courses for the term. I selected Marxist Sociology and Sociology of Development from the list he gave me. He was sad that I would not follow his course on European Radical Sociology, which focused on Jews and their persecution.

My principal teacher, Tom Bottomore, was a Marxist scholar. When I met him in his office room, I was overwhelmed by heavy pipe smoke. He was a friendly teacher. He told me he had spent time writing the well-known Sociology textbook for Indian students. He wore a thick tweed jacket with leather patches on his elbows. The other teacher was Prof Ron Dore, a development expert who published many books on Japan’s land reforms, city life, and industrial development. His famous book, ‘ Diploma Disease’, discussed the pitfalls of the traditional education system in Sri Lanka. He did not smoke. Once, he saw me smoking, and a few days later, when I visited him, he sarcastically remarked that pipe smoking is an emblem of the bourgeoisie, not the proletariat. Ron was the only IDS Fellow who did not profess Marxist thoughts.

By the end of the first term, I was well-adjusted to the university community, which was warm and friendly. Listening to debates over a pint of beer at the IDS bar in the evenings became my habit. I learned a lot from such debates and discussions. Two doctoral students from Sri Lanka often joined me at the bar. One of them, Newton, urged me to read Das Kapital as early as possible. It was a pleasure to listen to his stories and to watch how he explained complicated social theories with his fieldwork findings in the Kandyan countryside in Sri Lanka.

Tilak, the other doctoral student, told me to avoid visiting Brighton City on Sunday mornings. He said droves of ‘punks’ descended on the Brighton beach from London on Sundays, and the two piers were their favourite joints. They came in noisy motorcycles and wore dark denim jackets and silver chains. They had heavy boots with silver buckles. Their hairstyle, Tilak said, was short and coloured, which gave them the title of ‘punks.’ They were loud and carefree. He said that he had lived in an apartment not far from the Brighton Piers and avoided the town on Sundays.

I became curious about the punks and their subculture, which emerged in the 1970s in the UK. It was a youth subculture, and the youth wanted a cultural revolt and believed it was underway in the UK. People feared punks and thought that they would target, harass, and assault them. But punks were not hooligans or criminals. They demanded a cultural space for the youth to play a vital role in society. In this sense, the label ‘punk’ is for young people who want space to reimagine, discover, and challenge the society in which they are coming of age.

One Sunday morning, I went to Brighton Beach to see them. Around 10 am, I could hear motorcycles coming along the railway station road to the city’s heart. I counted 21 motorcycles, each carrying two punks. They parked their motorbikes and walked around shouting and laughing. One punk got knocked down by a car when he tried to cross the road recklessly. He was limping but refused to seek medical help.

Bands such as Sex Pistols and the Damned were popular in the UK in the 1970s. They gave punks some recognition and respect among the youth. Skirmishes with authorities were the centre pieces of the subculture that exposed chaos, ugliness, and outrage against the state in the 1970s. They showed anti-establishment sentiments and their desire for personal freedom. They hated hippies’ laid-back attitudes. Punks thought hippies who guided some youth in the 1960s to seek freedom just sat around and got high on drugs rather than getting out to act.

While settling down in England, I felt hidden and persisting ambivalence among some locals in Brighton towards towards South Asians. Once, at a small shop in Brighton, its owner told me that he would not sell anything to Asians, especially to Pakis. He thought I was a Pakistani. He felt I should live in my own country, not his country.

I thought he had expressed a general feeling among the English about Asians. An Indian friend at the university told me she had a similar experience at a bric-a-brac store in Brighton where the shopkeeper told her to “go home to your country. This is not your country.” When she ignored him, he became aggressive and started telling her rude jokes about Asian women, and my friend did not understand most of what he had said.

Features

Trump’s Delinquent War Game: No Early End in Sight

It is fruitless analyzing US President Trump’s reasons for going to war with Iran or the conflicting outcomes he says he is looking to have in the end. It is quite possible that he may have made the decision to attack Iran after being cajoled by Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu. It is a good time to attack because Iran is at its weakest moment yet posing an imminent threat warranting a pre-emptive attack. Strange and circular reasoning is needed to justify unnecessary wars.

True to form, Trump did not consult any of his western allies the way his predecessors did in similar situations. He ignored NATO as much as he ignored the UN. Nor did Trump go through the internally established broad consultation and focused decision making processes that US presidents usually undertake before committing American forces abroad. The Congress, the institution under Article I of the American Constitution, was also habitually ignored .

It is likely that Trump secured tacit support from other Middle East governments, especially the Gulf states of Kuwait, Saudi Arabia, Bahrain, Qatar, UAE and Oman that are Iran’s neighbours. The latter may seem to have been hoping to have it both ways – letting US and Israel take out Iran’s reprehensible regime while appearing to stay neutral in the fight. That calculation or miscalculation explosively backfired when Iran started firing drones and missiles not only into Israel but practically into every Arabian (Persian) Gulf country, hitting not only American bases but also civilian centres. The welcoming reputation of the Gulf countries as secure oases for foreign investment, tourism, sports and entertainment has been seriously shattered.

Escalating War

In addition to the six Gulf states, Iranian missiles have reached Iraq, Jordan and far away Cyprus. Even Turkey and Azerbaijan have been targeted. Israel has been hit and has suffered casualties far more in the few days of fighting than it has in all the past aerial skirmishes. The US outposts are under attack as well. The Embassy in Kuwait was hit on Monday. The next day two drones fell on the US Embassy in Riyad, Saudi Arbia, apparently the most fortified American outpost abroad. This was followed by drone attacks on the US Consulate in Dubai and on the American military base in Qatar, the largest in the region. Six American servicemen have been killed and 18 injured in the first four days of the war.

The Trump Administration that has been notorious for picking countries to deny US visas, is now asking Americans to return home from 14 Middle East countries for the sake of their own safety. Washington has closed its embassies in Riyadh and in Kuwait and has ordered non-emergency staff and families to depart from its other embassies in the region. But leaving the embattled region is not easy with flights cancelled and air space closed. Belatedly, the State Department is scrambling to make arrangements to help stranded Americans find their way out by air or by land to neighbouring countries. It is the same story with governments of other countries whose citizens are living and working in large numbers in the Middle East. The monarchs of Middle East depend on migrants of many hues to do their blue collar and white collar labour while keeping their citizens in cocoons of comfort. That equilibrium is now under threat.

Iran’s losses are of course significantly higher, already hit by over 2,000 Israeli and US missiles reaching multiple targets in 26 of Iran’s 31 provinces. Over a thousand people have been killed including 180 students in a girls’ school in the south. Buildings and infrastructure and installations are being devastated. Israel has opened a full second front in Lebanon using the thoughtless Hezbollah’s aerial provocation as excuse for once again badgering Beirut and its suburbs. A week into the war there is no early end in sight. Only escalation.

Not only Iran but even the US is extending the waves of war. A US submarine torpedoed without warning and sank the IRIS Dena, a Moudge-class Iranian frigate, in the Indian Ocean not far from Galle. The frigate had about 130 sailors on board and was sailing home after participating in the International Fleet Review (IFR) and multilateral exercise, MILAN-2026, organized by the Indian Navy at Visakhapatnam. The frigate was reportedly not carrying weapons in keeping with the protocol for international naval exercises. Also, according to reports, Americans were in the know of the Fleet Review in India and its participants. Yet the US Secretary of War, Pete Hegseth, went on public television to say: “An American submarine sunk an Iranian warship that thought it was safe in international waters,. Instead, it was sunk by a torpedo. Quiet death.” How tragically surreal!

It fell to little Sri Lanka to respond to the distress call of the sinking sailors. Sri Lanka’s navy and emergency services have done an admirable job in fulfilling their humanitarian responsibilities. The Sri Lankan government has also handled a difficult situation, complicated by a second Iranian ship, with poise and purpose. On the other hand, unless I missed it, I have not seen any official reaction by the Indian government to the reckless sinking of one of its guest ships. An opposition parliamentarian of the Congress Party, Pawan Khera, has been cited as asking on X, “Does India have no influence left in its own neighbourhood? Or has that space also been quietly ceded to Washington and Tel Aviv?”

India is not the only one that has ceded space and time to the bullying whims of Donald Trump. With the exception of Spain, the entire West is literally genuflecting for fear of getting hit by tariffs. Notwithstanding the US Supreme Court ruling much of Trump’s tariffs to be illegal, and a Federal Court now ordering that the collected monies should be paid back to those who had paid them. The situation is a far cry from the European reaction and the public lampooning of Bush and Blair when they went to war in Iraq two decades ago.

The Missile Math

Two factors may objectively determine the course and the duration of Trump’s war: weapons stockpiles and the oil and natural gas markets. Higher prices of oil and natural gas will increase domestic pressure on Washington to find an offramp to the war sooner than later. Other countries may have to suffer not only higher prices but also shortages of fuel. The weapons are a different matter.

The ongoing aerial warfare involves the use of drones and missiles to attack as well using defensive missiles to detect and destroy incoming projectiles before they hit their targets. After the beating it took last year and this week, Iran has no missile defense system to speak of, but it has both a stockpile of drones and missiles and capacity for rapidly producing them. The military question is whether Iran’s stockpile of offensive drones and missiles can outlast the combined defensive missile stockpile of the US, Israel and the Middle Eastern countries. There is no clear answer, only speculations about Iran and US concerns over its own stockpile.

The “troubling missile math,” as it has been called is underscored by the concern expressed by US Secretary of State Marco Rubio, that Iran has the capacity for “producing, by some estimates, over 100 of these missiles a month. Compare that to the six or seven interceptors that can be built a month.” The worry is also about the depleting impact that the extended use of interceptors against Iran will have on American stockpiles elsewhere in the world, especially in areas involving China. That is part of the standard military calculation. What is bizarre now is that after starting the war on a whim last Saturday, Trump is convening a meeting within a week on Friday with weapon manufacturers to urge them to produce more.

Secretary Rubio also added that destroying Iran’s missile capacity is the goal of the US campaign. Iran’s missile capacity involves different missiles with different flight ranges. The shorter the range the larger the stock. Iran does not have the standard two-way intercontinental ballistic missile, and it is nowhere near developing them. The current Administration has recklessly claimed that Iran is capable of launching missiles to hit America and has unfairly named and blamed all previous presidents for not doing anything about it.

Trump’s predecessors were fully aware of America’s unmatched military superiority and Iran’s utter limitations. They were also aware that going to war with Iran to destroy its drones and limited range missiles will create more problems without solving any. The Obama Administration in consort with China, UK, France, Germany and Russia produced the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA) committing Iran to have nuclear programs for peaceful uses only. Trump tore up the Obama plan and instead of using the opportunity this year to create a new and stronger program, chose to start a war instead.

As things are, unless the US-Israel axis succeeds in literally obliterating all drones and missile production resources in Iran, Iran will retain the capacity to produce drones and short-range missiles with which it could torment its neighbours for long after Trump and Netanyahu declare the war to be over. It may never be a long-range menace – in fact, it never was – but it could become an even greater short-range nuisance.

The US is no longer indicating a time limit for the war to end. For Netanyahu, it is not going to be an endless war. Of the two, Israel might be having some clear objectives to be achieved before ending the war. For Trump and his Administration, on the other hand, the objectives of the war are chaotically evolving on a daily basis, and the world will have to wait till the man of the deal finds some outcome or outcomes that can be shown as success and call it quits.

Regime Change: Insult after Injury

Iran’s Supreme Leader and forty or so other top Iranian leaders were taken out in the first minute of the fight by “pinpoint bombing”, as Trump boasted in his auto-poetic truth social post. But the Iranian regime has not collapsed. It has shown remarkable structure and durability despite the death of its Supreme Leader. It is America that is showing its inability to contain its Supreme Leader from going berserk on the world through tariff and bombing terror – in spite of all the checks and balances that Americans thought they have constitutionally practised and honed over 250 years. It is also poetic comeuppance for the Iranian regime that, after 47 years, it should now face its undoing by an unhinged American hegemon for theocratically subverting the 1979 revolution from realizing any of its secular possibilities.

Trump now wants to add insult to injury by forcing himself into the succession process for selecting a successor to Ayatollah Ali Khamenei. Iran has a well-established succession process, almost akin to the conclave in the Vatican, in which a body of 88 elder clerics, the Assembly of Experts, are convened to elect through a secret vote the new Supreme Leader. Over the last few days, it has been widely reported that the late Khamenei’s 56 year old son Mojtaba Khamenei has emerged as the leading candidate to succeed his father as the next Supreme Leader. His political strength and leadership claim are reportedly based on his close connections to the powerful Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC).

Mojtaba is said to have been the shadow Supreme Leader in recent years making decisions in place of his ageing father. For that reason, he is reviled by Iranians who are opposed to the regime and who have been oppressed by the regime. There are also allegations and rumours about his amassing wealth and investing in properties and opening bank accounts in London and Geneva. At the same time, there could also be sympathy for him in the ruling circles because it was not only his father and his mother who were killed in the first minute bombing but also his wife and his son. While ideologically he has been a hawk, Mojtaba is also described as a “pragmatist.” Being pragmatic in the current context, according an unnamed Tehran academic, would imply that Mojtaba Khamenei will be seeking revenge for the US-Israeli attacks on his family and his country – not through victory in war but by ensuring “the survival of the Islamic Republic.”

President Trump is not bothered about the dynamics and nuances of Iranian leadership politics and has no hesitation in inserting himself into the succession process. In an interview with the American news website Axios, Trump has declared that he wants to be personally involved in the Iranian succession process, and that the selection of the younger Khamenei would be “unacceptable” to him, because “Khamenei’s son is a lightweight.” “I have to be involved in the appointment, like with Delcy [Rodríguez] in Venezuela,” Trump went on, because “we want someone that will bring harmony and peace to Iran.”

Comparing Venezuela and Iran is no less preposterous than the Bush Administration’s decision to invade Iraq in addition to Afghanistan in order to punish Al Quaeda for 9/11. Trump now appears to be seeking not a wholesale regime change but a retail leadership change in the old regime. This is only the latest addition to his lengthening wish list for the war with no method or plan to achieve any of them. Add to the growing list the news that the CIA is putting together a Kurdish insurgent force to foment “a popular uprising” within Iran.

That would be back to the future and the return of the CIA, but in a totally different situation from what it was 73 years ago when the CIA, in partnership with Britain’s MI6, staged the 1953 coup that ousted the government of then Prime Minister Mohammad Mosaddegh and reinforced the monarchical rule of Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, the Shah of Iran. The purported plan now is to arm and organize Kurdish forces in Iran and Iraq to engage the Iranian security forces and thereby to create internal spaces for Iranian civilians to come out to the streets and take over their country. Those who are entertaining this plan are also aware of its inherent dangers and cross-border and pan-ethnic implications for Iraq and even Turkey and Syria. Trump is reportedly aware of the plan but may not be bothered about its unintended consequences.

by Rajan Philips

Features

ARRIVING DOWN UNDER

We (my wife Esther, two children, Frances (two yrs six months) and Richard (six months), and myself left Katunayake airport for Australia at 4.30 pm on March 12, 1968, flying UTA French airlines.

The final day in Sri Lanka was quite a busy one, receiving our foreign exchange allocation only at 11.00 am that morning, then rushing back home for the trip to the airport. Having long worked as an engine driver for the CGR, it was my intention that our final trip in then Ceylon would be by train; as such we took the 12.45 pm train from Maradana and detrained at Katunayake station.

I had pre-arranged with the Station Master at Katunayake to have a fleet of taxis stand by to convey us (friends, relatives and ourselves) to the airport. The plane departed on schedule and from the moment it took off I was air sick all the way.

At Singapore there was a break of a few hours and I managed to get off into the transit lounge for a breath of fresh air which seemed to revive me. Esther and the children however, stayed on board the aircraft. Once the plane took off, I was again a victim to air sickness. Fortunately the seats behind had fallen vacant and I was able to bed down for the night. It was Esther who had a torrid journey, minding the two kids all the way.

I was woken up whilst the plane was flying over Central Australia and did see the morning glow light up the land. We arrived at Sydney in the morning and I was amused to see that as soon as the plane landed a man entered the plane carrying an aerosol can, the contents of which he sprayed around the interior of the plane. He was, I am told, the Quarantine Officer, carrying out his duties to ensure no ‘nasties’ entered the country.

Before we disembarked a pleasant surprise awaited us – a telegram from a pen friend of mine in Queensland welcoming us to Australia, was delivered to us. We had a two hour break at Sydney Airport before we caught our connecting flight to Melbourne (Essendon Airport).

It was a hot sunny day, the children were tired and grumpy and I called over at a food outlet to buy some drinks. All I had with me was a British pound sterling note. I gave them that and was given the change in Australian currency, which I had never seen before. I kept looking at it for a while, when the lady at the counter wanted to know what was wrong.

I told her I was migrating to Australia with my family and had never seen Australian currency before and was looking at it. She said, ‘please give it all back to me’, which I did. She then gave me back the pound note and said, “Welcome to Australia. I came here from Poland 10 years ago, I hope you settle in happily”. An auspicious start indeed to our life ‘Down Under’.

The family (my parents, brothers and sisters) were all gathered to meet us as I was the last member to migrate. The drive home was fascinating to say the least, the roads, bridges, lack of people on the roads, quiet traffic (with no cacophony of horns) made it all the more pleasant.

We were seeing television for the first time, and I thought to myself, how wonderful to ‘see the cinema come home’ as the day unfolded and we began to discover more delightful Australian customs and way of life. The following day, accompanied by a brother, I visited the local factories and businesses – Yakka, Ericsson’s, Nabisco Biscuits, Ford Motor Company – in search of employment.

I was flabbergasted to hear each one of them say I was too qualified for them and as such they could not employ me. This was indeed a new one for me. My brother explained, that they knew I was a new migrant and was looking for any type of employment to get settled, and then later on would obtain better employment commensurate with my qualifications. Thus all their training would have been in vain, not to mention the costs involved.

The following day I went to the City, accompanied by another brother. The train journey there and back, the ‘big smoke’ had me enthralled. We called at the recruitment office for both the Federal and State Public Services where forms were filled in and an application for employment lodged. Both agencies stated that it would be some months before I heard from them.

We next called in at the Australia Post recruitment centre as they were recruiting mail sorting officers and signed up with them to begin work the following Monday. The three months at the Postal Training School was interesting; one had to familiarize oneself with the various postal towns in districts and learn speed sorting. At the end of the three months I was given a bundle of 25 letters and had to sort it in a minute into postal districts, with only three errors allowed.

I was smart enough to work on the names in districts, in line with railway stations in various areas of the CGR – Matara, Badulla, Trinco, Batticaloa, KKS lines, thus being able to acquaint myself with the names quicker, and in the final test had only two mistakes.

As son as I had passed out from Postal School, I had a letter from the State Public Service offering me a clerical position (the choice was mine) at any of the following – the Department of Agriculture, Department of Health, Motor Registration Board, Grain Elevators Board and Fisheries & Wildlife Department. The last seemed very interesting and I picked it.

The postal authorities were unhappy to say the least when I resigned my position immediately after three months training (I now understood why I was earlier told that I was too qualified for employment). And so began a 25 year carrier with the State Public Service, which saw me serve in the same ministry, but various divisions – Fisheries & Wildlife, Conservation, Environment Protection Authority, Conservation & Natural Resources, Forest Commission, National Parks and Conservation & Environment.

Due to needs of supplementing my income, I obtained part time employment as an office cleaner with Brown’s Office Cleaning Services and worked for them for 15 years. They had contracts for cleaning offices in the City of Melbourne. A number of Sri Lankan immigrants worked for them supplementing their income. Thus began an extra stint of duty, leaving one’s day job, which ended t 4.30 pm.

Whilst the work was not too arduous the long hours were very demanding. I worked three hours each weekday evening, beginning at 5.00pm. By the time I reached home on public transport, it was well past 9.00pm and I was completely exhausted, especially during the summer months. Fortunately although it was part time work, I was also entitled to sick leave and annual leave.

Esther always wanted to remain at home and look after the kids. This was indeed a most demanding role for her, in that at one time we had the five kids attend five different Catholic schools in the area, which were graded senior, junior, high school (college) and then also segregated between boys and girls. She spent some 15 years driving them to the various schools and back.

One of the first things my father got me to do on arrival in Australia, was to fill in an application form with the Housing Commission of Victoria for a home of our own. This they told us would take anything up to three years before we were allocated one.

After an initial stay of four months with my parents at Broadmeadows, we decided to look for our own accommodation (a flat or house), but found that no one was keen to rent houses to people with children or pets. Finally we were able to locate a large flat (over a small shopping centre) in East Thornbury, where my parents lived when they moved to Australia.

The Estate Agent amazed me when I told them we had children saying, “we love children, yours are welcome.” When I said I had no Australian references, which everyone wanted, they said “If you were good enough for the Australian Government, you are good enough for us”. They were truly amazing and people with a heart.

We lived at East Thornbury for three years before we were given a choice of selecting a house from one of six being built at Broadmeadows West. This we did and this has been our home for the past 38 years. Initially it was difficult as it was a new area, with no street lighting and away from most shopping amenities, but over the years much development has taken place in and around the area.

At the early stages, we had most services delivered to the door – bread, milk, dry cleaning, fruit & vegetables, newspapers, the onion & potato man, mail etc. Over the years the services have dwindled (with progress) and today only the mail and newspapers are delivered.

After 25 years service with the State Public Service, I took the opportunity of ‘early retirement’ being offered by the public service and retired in April 1993.

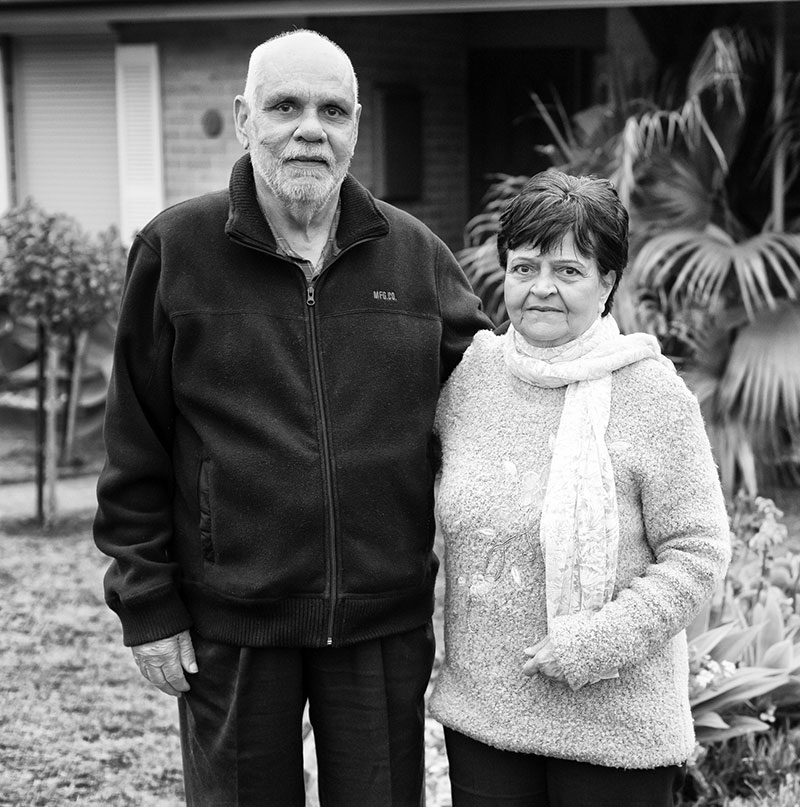

by Victor Melder

Features

How Helmut Kohl braved the tsunami, P-TOMs and Kadirgamar assassination

This is the place to introduce the episode of ex-Chancellor Helmut Kohl of Germany. “This legendary unifier of post war Germany was at a small hotel in Hikkaduwa undergoing Ayurveda treatment when the Tsunami struck. A German Minister who owned a house in Hikkaduwa and visited Lanka regularly had recommended Ayurveda treatment to The Chancellor and head of her party- the Christian Democrats.

The German Embassy was at its wits end because Kohl had disappeared without a trace. They contacted us and we activated our Grama Sevaka network to find that Kohl had been taken to the safety of his home by a hotel employee. When we offered to send a helicopter to bring him to Colombo the Chancellor had replied that it was not necessary as he was well looked after by his host. He came by car the following day in order to thank CBK for her help.

I went to President’s House with Kohl who seemed quite relaxed in his coloured shirt, crumpled pants, a grey seersucker coat and rough boots. He was full of praise for the Sri Lankan people who had helped him and all the tourists in distress due to the Tsunami. Kohl said that he wanted to help in the rehabilitation of the south in his personal capacity. When he got back to Germany he set up a group of rich friends called “Friends of Helmut Kohl” who sent money to build a hospital in Mahamodera, Galle.

The money was lodged in the German Embassy. But the usually lethargic Health department dragged its feet on the construction work on the guise that the money was not sufficient for their grandiose hospital plans ignoring the value of the superb gesture by Kohl. Unfortunately he died before the completion of the project and therefore could not keep his pledge to come to Galle for its opening.

Later in time I was a member of a Parliamentary delegation led by Speaker Karu Jayasuriya which included Sampanthan, Rauf Hakeem, Anura Dissanayake and several others. I suggested to our group that we pay a belated tribute to Helmut Kohl who had died a few months previously. This was immediately welcomed by the parliamentarians and the organizers of the tour and we jointly paid our heartfelt tribute to a great friend of Sri Lanka who was an eye witness to the success of our rehabilitation effort.

Post Tsunami Operational Management Structure (P-TOMS)

The Tsunami was particularly harsh on the eastern and northern coastline because it was directly in the way of the giant waves created in Indonesia and deflected to our shores. It also created a transformation of the political scene and the nature of the war. The LTTE had invested considerable resources in building up its “Sea Tigers”. They wanted control of the northern seas in order to increase their supply of weapons and ammunition. The Sea Tigers established a presence in east Thailand so that arms could be purchased from Cambodia, Vietnam and Thailand. The fighting in the Indo-China theatre was over and the cut rate weapons market was flourishing.

Our embassy in Bangkok had an army officer who was monitoring terrorist activities but he was helpless because Thai officials in the lower echelons were in the pay of the LTTE. In addition to that problem, the mediocre officials of our Foreign Ministry were no match for the determined LTTEers one of whom had married an influential Thai lady. With money coming in from expatriates they had even set up a shipping line which was so well run that they could finance weapons buying for the LTTE with its profits.

We had received intelligence that the LTTE was preparing for a major “Sea Tiger” operation from their base in Mullaitivu. This base area concept shows the advanced thinking of the LTTE which was attempting – then unsuccessfully – to even manufacture a low cost submarine. Fortunately for us the Tsunami wiped out the base of the “Sea Tigers” together with many of their assets such as boats, proto-type submarines and diving gear.

True to form they sent signals for talks which they had earlier broken. Their diaspora had mounted a campaign to collect funds for rehabilitation. At this stage the UN got into the act and with the World Bank and IMF persuaded the CBK government to consider a power sharing arrangement principally for the rehabilitation of the North and East. It was to be called P-TOMS. CBK appointed Jayantha Dhanapala as the head of SCOPP – a secretariat to coordinate the relief effort in the North and East. The World Bank appointed Peter Harrold, its representative in Colombo, to coordinate the P-TOMS effort with SCOPP.

Estimates were made by SCOPP regarding the amount necessary for the rehabilitation of the North and East. This budget became the talking point of several successive regimes who promised to allocate such funds in exchange for Tamil votes in the North. Mahinda Rajapaksa’s agents held this figure as a bait to promote a boycott of the Presidential poll in 2005 which threw the election which was in Ranil’s pocket to MR thereby changing the destiny of the LTTE as well of the country. [MR cleared the 50 percent hurdle by only 25,000 votes].

Perhaps to strengthen the push for P-TOMS, Kofi Annan the Secretary General of the UN arrived with a large contingent of staffers and I was asked to meet and greet him in Katunayake. We gave Annan a grand welcome but he seemed distracted and was only interested in getting his Swedish wife who was hanging back, into the spotlight. CBK had several discussions with him but we ran into a snag in that he wanted to visit the North and meet Prabhakaran.

Perhaps some of the big powers had got to him as he was in the midst of a scandal about his son from his first marriage who was facing charges of corruption. The scandal was rocking UN headquarters. Annan who was elevated from his earlier status as a UN functionary to satisfy African members, was according to several biographers, indebted to the west and could not end his tenure to the satisfaction of the majority of the UN membership.

CBK, already under pressure for mishandling the P-TOMS campaign, was adamant that Annan should not meet the LTTE which would have given the terrorists parity of status with the SL state. Since such an interpretation was circulated by virtually all political parties in the South she was pushed to a very difficult position. After much discussion Annan settled for a helicopter tour of the North. I found that he was a weak leader who was led by his nose by Mark Mallock Brown – his chief of staff, who had been in charge of UN operations even during its disastrous forays in the Congo.

Mallock Brown was later identified as a camp follower of the West who compromised the credibility of the UN. I have memories of Mallock Brown holding forth on their next step here while Annan and Dhanapala were mere passive listeners. This Western initiative of P-TOMS did not finally see the light of day. But it split the ruling coalition of the PA and JVP irrevocably and Mahinda Rajapaksa burnished his credentials as an opponent of the project. He became popular with the PA and its allied parties over and above CBK.

When the P-TOMS project was to be placed before Parliament Mahinda as Prime Minister refused to present it on the floor of the House. CBK was too weak to dismiss him partly because Lakshman Kadirgamar also was a strong opponent of P-TOMS. Instead she got Maithripala Sirisena to present the proposal. But the Opposition which was joined by the JVP including its functioning Ministers, took to the streets. The JVP members demonstrated and disturbed the proceedings from the well of the House and then resigned “en masse” from the government putting its majority in jeopardy. Mahinda’s anti-P-TOMS stand endeared him to the JVP, which had earlier preferred Kadirgamar to him, and helped him to garner votes which went a long way in ensuring his ultimate victory. He had become so powerful that CBK had no option but to accommodate him.

Assassination of Lakshman Kadirgamar

Another blow was struck at CBK and the government by the I TTE when they assassinated Lakshman Kadirgamar near the swimming pool of his house. He had a successful kidney transplant in India – with a Buddhist monk from Balangoda donating a kidney – and was asked to swim regularly as exercise by his doctors. I knew of this arrangement because when we travelled together he always asked the Foreign Office to put him tip in a hotel with a heated swimming pool.

He was about to enter the water in the swimming pool when a LTTE sniper shot him through a window in a neighbourhood flat. This dastardly crime wits condemned unanimously by the international community. India sent her Foreign Minister to attend the funeral. Ksdirgamar’s death brought CBK’s Government to the brink of collapse. The JVP though leaving the Government respected LK and paid a tribute to him by arranging for their leaders to follow his hearse on foot to Kanatte.

It must be mentioned here that LK nearly pipped Mahinda for the post of PM in 2004. He had the backing of the JVP who wanted CBK to appoint LK and in the alternative appoint Maithripala Sirisena as PM. He was also supported by India but CBK was afraid that Mahinda will break up the party if he was deprived of the Premiership. After LK’s demise she undertook a mini reshuffle and Anura Bandaranaike had his ambition of being Foreign Minister realized.

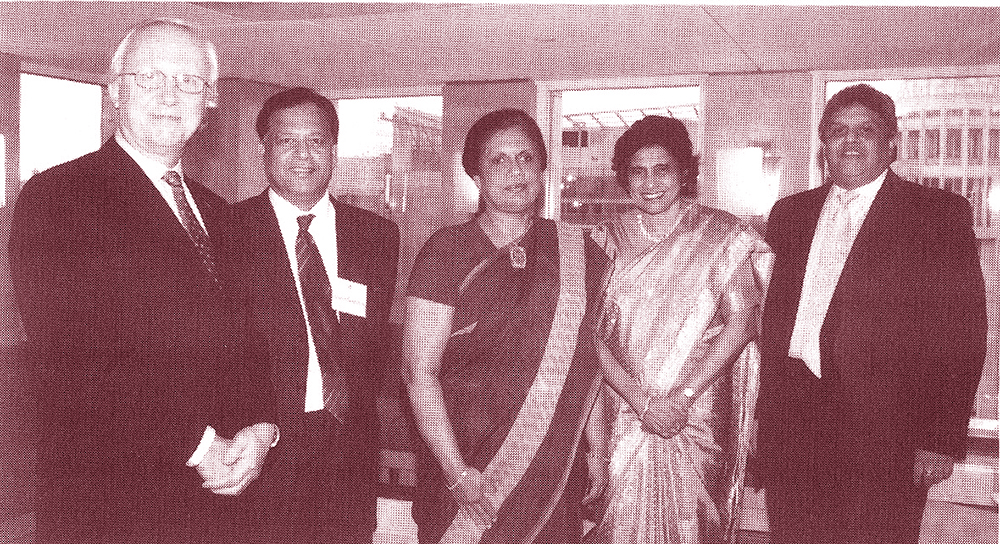

To succeed him as Minister of Industries and Foreign Investment she appointed me in addition to my portfolio of Minister of Finance. Arjuna Ranatunga was the Deputy Minister of Industries and I left most of the administrative work to him. When we had an investment promotion meeting in Delhi I invited Arjuna and Aravinda de Silva to be our delegates and they stole the show among the cricket mad Indian investors. All the tables at dinners hosted by us were taken and we had many friends appealing to us to get them reservations even at the last minute.

We had such good relations that I was invited to take part in popular TV talk shows. I remember that Shekhar Gupta invited me for a discussion on our health services with Kajol – the top Hindi film actress who was brand ambassador for Narendra Modis “clean Bharat” campaign. She was a charming young lady who recounted her enjoyable stay in Sri Lanka when she accompanied her mother Tanuja who was shooting a film in Colombo with Vijaya Kumaratunga as her co-star.

After LKs murder the fear of the LTTE was so strong that CBK could not even attend the funeral ceremony. PM Mahinda Rajapaksa represented her. This death was a bitter blow to me because as an old Trinitian friend he would always consult me on party matters. I still have a letter he wrote to me about a coffee t able book on the art of Stanley Kirinde which he sponsored in honour of our mutual college friend.

(This book is available at the Vijitha Yapa bookshops)

(Excerpted from vol. 3 of the Sarath Amunugama autobiography)

-

Features6 days ago

Features6 days agoBrilliant Navy officer no more

-

News2 days ago

News2 days agoUniversity of Wolverhampton confirms Ranil was officially invited

-

Opinion6 days ago

Opinion6 days agoSri Lanka – world’s worst facilities for cricket fans

-

News3 days ago

News3 days agoLegal experts decry move to demolish STC dining hall

-

Features6 days ago

Features6 days agoA life in colour and song: Rajika Gamage’s new bird guide captures Sri Lanka’s avian soul

-

News2 days ago

News2 days agoFemale lawyer given 12 years RI for preparing forged deeds for Borella land

-

Business4 days ago

Business4 days agoCabinet nod for the removal of Cess tax imposed on imported good

-

News1 day ago

News1 day agoWife raises alarm over Sallay’s detention under PTA