Features

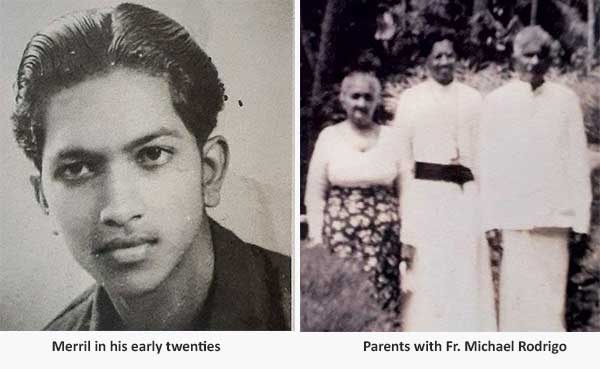

My beginnings at Pallansena and how my parents and the village influenced my life

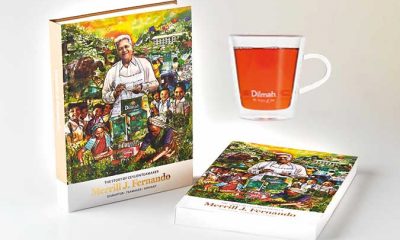

The Merril. J Fernando autobiography

Excerpted from The Story of the Ceylon Teamaker

Ninety-three years ago – in 1930 – I was born to a middle class family in the village of Pallansena, as the youngest of the six children of Harry and Lucy Fernando. My sister, Agnes, was the eldest and then came brothers Lennie and Pius, followed by sisters Doreen and Rita. My family roots can be traced back to this village where, from the time of my great-grandparents, ours had been a leading family.

Pallansena is situated about 15 kilometres north of the Colombo International Airport. Many decades ago, long before the airport was even thought of, it was a small village of about 100 closely-knit families. As common to such villages then, most of the families were connected to each other, either through blood or marriage. Irrespective of such connections, all those who lived in the village comprised one large family, held together by religious and cultural commonalities, shared responsibilities, and concern for one another.

Pallansena is no longer a village though, having gradually been overwhelmed by the urbanization and commercialization that is changing the charming landscape of this country, all over. That once-serene rural community is now a crowded suburb of the more densely-populated Kochchikade. The land on either side of the road that I, as a child, used to walk along on my way to the Pallansena village school, was lined with coconut plantations. Today, only a few scattered patches of coconut remain.

Much of the old plantation land is now built over, with modern residences, shops, hotels, and guest houses. In the village of Pallansena itself, most of the graceful old houses with wide verandahs and central courtyards, set deep in large, tree-laden gardens, have disappeared. Instead, unlovely facades of brick, glass, and concrete with barred windows line the roads on both sides.

Many of the houses then, large and small, had intricate wooden trellis frontages, which gave privacy but did not hinder ventilation. These have now been replaced by featureless iron and masonry grills. The very few old houses that remain still evoke memories of a vanished appeal. However, unlike in my youth, they too are now surrounded by high parapet walls and, therefore, rarely seen.

The Maha Oya and the Hamilton Canal which flows into it, in my youth clearly visible through the trees, and the houses which lined the gravel road running past the Our Lady of Seven Sorrows Church, have been obscured by row upon row of buildings. The once-pristine surface of the water and the clean, sandy banks, lined with rushes and other water plants, are today littered with imperishable plastic debris.

Instead of the weathered, light wooden canoes and rafts which used to be drawn up on the banks, far apart from each other, hundreds of garishly-coloured fibre-glass motor boats are anchored, shoulder to shoulder and bow to stern, at the edge of the water. The muted splash of wooden oars has been replaced by the clatter of high-powered outboard motors, rudely cleaving the surface. The broad-beamed padda boats with sloping cadjan canopies, steered by weather-beaten boatmen wielding long wooden poles, transporting both cargo and people, were another common feature along the canal in my early youth. They too disappeared many decades ago.

In my youth the community co-existed in gentle harmony with its surroundings. But, today, the unforgiving influence of commercial prosperity has been imposed on a once-tranquil society. Signs of affluence are visible and numerous, but they have come at a heavy price, which has been paid by a vulnerable environment.

Formative influences

Pallansena, like most villages on the western coast then, especially north of Colombo, was almost entirely Catholic, the result of the Portuguese influence, which first made its presence felt in Ceylon at the beginning of the 16th century. Religion was both a powerful unifying and guiding force and all families were raised on the strict spiritual principles of the faith. The Parish Priest was a man of great authority in the community, a sort of a benevolent dictator, a feature common to all such societies.

The village church used to be the centre of both religious and social activity. As a youth I was an altar boy in the church, then considered a proud distinction. Despite the many developments that have changed the face of Pallansena over the years, the church continues to be a powerful influence in the community. In a society which has evolved almost beyond recognition, that one feature has remained a constant in the nine decades since my birth.

My parents, especially my mother, raised me strictly according to sound, time-tested values, centred around the family and our faith. She was very religious and civic-minded and from my childhood, instilled in me the need to help our less-affluent neighbours. She visited other families regularly and, despite my vocal protests, quite often shared with the children of these families the prized goodies that I received, such as cakes, chocolates, and sweets.

In that era, in communities such as Pallansena, whilst there was no significant poverty, there were still a few underprivileged families. To my mother, helping such people was a serious moral obligation. She was a woman of great generosity and humility and was truly loved by the people of the village. She is still spoken of with much affection and gratitude by the older folk of the village, especially those who benefited from her compassion.

Neighbours reciprocated my mother’s many acts of kindness by frequently bringing her their home-grown fruits, vegetables, and traditional home-made sweets. As she sat in her verandah, always with rosary in hand, passing neighbours would stop and talk to her. They would also offer to buy her groceries and run other little errands for her. Sharing and caring were endearing features of our village, undoubtedly mirrored across many similar communities then, unlike in the highly-urbanized and commercialized age we live in now.

The principles that I still live by were articulated for me, very early, by role model example by my parents, especially my mother. They were conditioned largely by the teachings of my religion and the decent ethics of life, which are common to all great religions and principled societies. Since moving out of that somewhat-cloistered community and into the larger world of industry and international commerce eventually, I have been exposed constantly to different learnings and varied influences. However, the strength of that early indoctrination is such that I have remained true to those principles of conduct and interaction. On reflection, I feel comfortable with myself today because my basic values have not changed.

In the environment I was brought up, people took time and effort to care for each other. The concern that people of the village had for each other was clearly demonstrated, in times of both grief and joy. For example, when there was a funeral in the village, neighbours would send the mourning family meals for three days. Similarly, when there was a wedding, neighbours would send dinner to the wedding house on the pre-nuptial night. These traditions were of great practical benefit, intended to reduce pressure on the family concerned, enabling them to concentrate on the event.

For generations my ancestors had worshipped at the Pallansena, Our Lady of Seven Sorrows Church. My maternal great-grandparents, Petrus Perera and Anna Marie Perera, passing on in 1881 and 1901 respectively, are interred within the southern wing of the church, their final resting places marked by two stone tablets set into the church floor. Despite the many feet of worshippers which have trod on them for over a century, the dedications etched into the slabs are still very clear. Apparently, this unusual distinction had been extended to these two ancestors of mine, on account of their generosity to the church.

The spacious grounds on which the church now stands had been gifted by these two, whilst they had also contributed generously towards the construction of the church itself. The incumbent priest’s residence, a beautiful, heavily-timbered, two-storeyed, Dutch-styled house, still elegant despite some indelicate, subsequently introduced modern flourishes, had also been built by them.

They had both been well-reputed Ayurveda physicians, especially known for the treatment of cataract and other eye diseases. My grandmother and grand-aunts continued this healing tradition. I recall that there would be many patients consulting them every day, with the numbers increasing on weekends.

They also made a very special herbal oil which, apparently, was guaranteed to keep hair black, well into old age.

My brothers and sisters used that oil and retained black heads of hair, well into their seventies. I used it in my teens. It had a very strong, highly-aromatic scent, but in my view, not unpleasant. However, since my schoolmates objected to the smell, I stopped using it very early. This wonder oil was distilled from a mixture of rare herbs and ghee, all the ingredients being boiled together in copper cauldrons, over wood fires, for three weeks.

Sadly, none of our younger family members learned the formula for this healing oil. I still have a thick head of hair, but it has been silver for a long time. Perhaps, instead of yielding to my schoolmates, I should have continued to use the oil!

The medicines for the treatment of eye diseases were distilled from a variety of herbs, which were crushed and mixed with other ingredients, including mothers’ breast milk. Often, in my youth, I was frequently given the embarrassing assignment of approaching breast feeding mothers in the village and asking for spoonsful of milk. It was always readily given, though.

My grandmother was a heavily-built lady who spent most of her time in a comfortable chair, with her walking stick beside her. As a playful little boy, I used to tease her by hiding it frequently and my aunts had to retrieve it repeatedly, scolding me all the time. In her annoyance at my harassment she used to threaten me. It was then fun for me, but I realized later how irritating I would have been to her.

My two aunts were very religious, always praying to God for the welfare of the family. I would ask them if they were praying for me, too. The answer was always a very firm NO, because I used to annoy my grandmother all the time. No one knew my grandmother’s exact age, but she lived a comfortable life for over 100 years.

My parents

I truly miss the village life of my early youth, the transparently genuine values of simple people — kindness, cordiality, love, and concern for one another and especially the needy were the virtues that held such societies together. Those values are unknown in big cities today. I miss the fresh air, the clean rivers and canals, sea bathing, and the furtive swimming outings with friends of my age in the Maha Oya, which flowed behind my home. My pet dog, Beauty, a Golden Retriever, would also jump into the water with us and stay at my side as long as I was in the water. Such faithfulness is still seen amongst animals but rarely with people.

My mother was very protective of me and terrified of my swimming. She did not allow me to swim either in the river or the sea. Invariably, even on our secret swimming escapades, she would appear on the bank within minutes of us entering the water and scold my friends for having persuaded me to get in, although it was actually on my invitation that we were in the water. My friends were always in awe of my mother. Despite her naturally kindly nature, when angry she could be formidable.

On weekends I used to get together with a few of the village boys and play cricket, football and ‘elle’ on the road. The latter game, a simplified version of American baseball, would attract others from the village and soon we would have as many as 20 people competing. It was great fun, with the winners eventually treating the losers with king coconut plucked from a nearby tree.

Those were wonderful times in a simple village society, where we all treated each other in a spirit of equal friendliness and sharing. Many of my friends were from poor homes in the village, but such differences did not matter. Very few of my village friends are alive today.

My mother was my role model in my early years and became a defining influence in my development as an adult as well. She always represented an uncompromising moral power. Her devotion to the family was the driving force and purpose of her life. As a typical old-fashioned housewife, she did most of the cooking, producing outstanding food of our preference.

She had a very efficient woman, Isabel, to assist her in both housework and in the kitchen, but she insisted on doing much of the cooking herself. To this day, I try to prevail on my cooks to use the ingredients she relied on. She roasted and prepared all the spices and other ingredients at home. The tempting flavours and the heady fragrance of spices, which Ceylon is famous for, were ever present in our home.

Isabel was a middle-aged lady who had been working in my parents’ home for many years and was very much part of the family. In ensuring that the children of the family, especially I, conducted ourselves well, she exerted almost as much authority as my mother did. In our household there was no visible master-servant distinction. That was another lesson I learnt at a very early age from my mother: irrespective of station in life, mutual respect was a condition to be observed in all exchanges, transactions, and relationships.

When she was about 80 years of age, my mother had a serious fall and fractured her hip. I was holidaying in Nuwara Eliya at that time and rushed back on hearing the news. She was admitted to hospital in severe pain and I contacted my friend, Dr. Rienzie Pieris, Senior Orthopaedic Surgeon, who operated on her immediately. Three weeks after the surgery she was released from hospital and with some difficulty I persuaded her to stay in my home in Colombo, for her convalescence before returning to the village.

My mother occupied the guest room in my house and was provided full-time professional nursing care, with my domestic staff also dancing attendance on her. I was delighted that she was now in my home. However, after a few days, my mother pleaded to be sent back to her Pallansena home. Despite the special attention and comforts I provided, she was unhappy away from her familiar environment and her friends. I understood her need and reluctantly took her back to the village, though she was deeply apologetic for disappointing me by her refusal to stay with me.

She refused to undergo physiotherapy after she returned to the village. No amount of persuasion regarding the importance of post surgical therapy could change her mind. As a result, despite the corrective surgery, she was unable to walk unaided and for the rest of her life was compelled to use a wheelchair. However, my widowed sister Doreen took great care of her.

I used to visit regularly, taking with me things which she enjoyed. Despite her condition, she continued to share these with others. Even the tea that I provided her from my company was parceled and shared with neighbours. Since she was now unable to do any housework, she used to spend most of her time in a special chair placed in the verandah, quite often with the holy rosary and reciting her prayers. Whenever I visited her, the first words to me would be, “Son, I am praying for you all the time; God will always bless you.”

In her last year, though she would greet me affectionately whenever I visited, my mother failed to recognize me, which distressed me deeply. She acknowledged only Doreen, her constant companion and carer. I realized then that her end was near and prayed to God for his blessings. On April 6, 1988, at the age of 98-years, 17 years after my father’s death, she passed into the arms of Jesus Christ. I had lost my great treasure.

During her funeral, which was held at the Pallansena church, there was a torrential downpour lasting about 15 minutes. It was so unexpected and so intense that it seemed to me to be symbolic of the occasion.

My love and admiration for her have been constant. She taught me a great lesson in life – to love my neighbour as myself and to share with those in need. She instilled in me, at a very early age, the concept that moral values cannot be compromised, irrespective of circumstances or the nature of temptation. Not until I started working and earning did I realize the value of her personal ethic, which was reflected in her everyday life. I absorbed from her the principle that a man had a responsibility to his community. And, later, as I shared with the less fortunate, my earnings increased, my business prospered, and God’s blessings flowed in abundance.

My father, Harry, was a simple, humble, and extremely hardworking man. He worked a long day, leaving home at early dawn and returning very late in the evening. His last business was the manufacture and supply of building materials, red bricks and tiles especially, for construction companies and other customers, mainly in Negombo, which was about 10 kilometres away.

The material he produced was collected and delivered by both lorries and bullock carts. Often there were delays in the settlement of his dues and collection would require many visits to customers. He would make all such journeys either on foot or by bullock cart.

He was a man of reasonable means. I realized that because people regularly borrowed money from him. Collection of such debts was often a problem, with debtors constantly trying to evade him. Those who were spotted by him on his collection trips would then feel the rough edge of his tongue. My father was a stern man who never forgot the due dates of settlement and insisted on the timely discharge of obligations and responsibilities. It occurred to me then itself that money-lending was not a pleasant business.

My father sent us all to good schools and, within his means, provided for us well. That was quite sufficient to give us decent starts in life and all his six children did well for themselves. If he were alive today, he would be a very proud and happy man. Whilst my siblings were generally obedient, I think I was the only trouble-maker, especially in my early years. Though my somewhat erratic educational progress would have disappointed him, he ungrudgingly paid all my school and boarding fees.

In his final years he lived at home with my mother and my widowed sister Doreen and I were able to care for them in every way. As he grew older and dependent on others for his daily needs, he became a little difficult and would complain about Doreen, who was under great stress but managing very well under the circumstances. I used to console Doreen with the assurance that since she was looking after our parents, when the time came I would look after her as well.

My father passed away on February 11, 1971 at the age of 84 years. He lived a good, responsible life. I thank God that I was able to show him my love and gratitude for all he did for the family. I deeply miss my parents and the others of my family who have passed on. I believe that our family will reunite at the second coming of Jesus Christ.

In December every year I visit my village for an almsgiving ceremony, in memory of my parents and family members who have passed away. I give away a couple of hundred packs of dry rations, each sufficient to last a family during Christmas and New Year. A few remaining friends and their siblings show up and say, “Sir, can you remember, my brother used to play cricket and ‘elle’ with you?” I do recall them and feel blessed that I am now in a position to help them in various ways. The Parish Priest at Pallansena has been very useful in identifying such people in need and I have been able to channel my assistance through him.

Features

Indian Ocean Security: Strategies for Sri Lanka

During a recent panel discussion titled “Security Environment in the Indo-Pacific and Sri Lankan Diplomacy”, organised by the Embassy of Japan in collaboration with Dr. George I. H. Cooke, Senior Lecturer and initiator of the Awarelogue Initiative, the keynote address was delivered by Prof Ken Jimbo of Kelo University, Japan (Ceylon Today, February 15, 2026).

The report on the above states: “Prof. Jimbo discussed the evolving role of the Indo-Pacific and the emergence of its latest strategic outlook among shifting dynamics. He highlighted how changing geopolitical realities are reshaping the region’s security architecture and influencing diplomatic priorities”.

“He also addressed Sri Lanka’s position within this evolving framework, emphasising that non-alignment today does not mean isolation, but rather, diversified engagement. Such an approach, he noted, requires the careful and strategic management of dependencies to preserve national autonomy while maintaining strategic international partnerships” (Ibid).

Despite the fact that Non-Alignment and Neutrality, which incidentally is Sri Lanka’s current Foreign Policy, are often used interchangeably, both do not mean isolation. Instead, as the report states, it means multi-engagement. Therefore, as Prof. Jimbo states, it is imperative that Sri Lanka manages its relationships strategically if it is to retain its strategic autonomy and preserve its security. In this regard the Policy of Neutrality offers Rule Based obligations for Sri Lanka to observe, and protection from the Community of Nations to respect the territorial integrity of Sri Lanka, unlike Non-Alignment. The Policy of Neutrality served Sri Lanka well, when it declared to stay Neutral on the recent security breakdown between India and Pakistan.

Also participating in the panel discussion was Prof. Terney Pradeep Kumara – Director General of Coast Conservation and Coastal Resources Management, Ministry of Environment and Professor of Oceanography in the University of Ruhuna.

He stated: “In Sri Lanka’s case before speaking of superpower dynamics in the Indo-Pacific, the country must first establish its own identity within the Indian Ocean region given its strategically significant location”.

“He underlined the importance of developing the ‘Sea of Lanka concept’ which extends from the country’s coastline to its 200nauticalmile Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ). Without firmly establishing this concept, it would be difficult to meaningfully engage with the broader Indian Ocean region”.

“He further stated that the Indian Ocean should be regarded as a zone of peace. From a defence perspective, Sri Lanka must remain neutral. However, from a scientific and resource perspective, the country must remain active given its location and the resources available in its maritime domain” (Ibid).

Perhaps influenced by his academic background, he goes on to state:” In that context Sri Lanka can work with countries in the Indian Ocean region and globally, including India, China, Australia and South Africa. The country must remain open to such cooperation” (Ibid).

Such a recommendation reflects a poor assessment of reality relating to current major power rivalry. This rivalry was addressed by me in an article titled “US – CHINA Rivalry: Maintaining Sri Lanka’s autonomy” ( 12.19. 2025) which stated: “However, there is a strong possibility for the US–China Rivalry to manifest itself engulfing India as well regarding resources in Sri Lanka’s Exclusive Economic Zone. While China has already made attempts to conduct research activities in and around Sri Lanka, objections raised by India have caused Sri Lanka to adopt measures to curtail Chinese activities presumably for the present. The report that the US and India are interested in conducting hydrographic surveys is bound to revive Chinese interests. In the light of such developments it is best that Sri Lanka conveys well in advance that its Policy of Neutrality requires Sri Lanka to prevent Exploration or Exploitation within its Exclusive Economic Zone under the principle of the Inviolability of territory by any country” ( https://island.lk/us- china-rivalry-maintaining-sri-lankas-autonomy/). Unless such measures are adopted, Sri Lanka’s Exclusive Economic Zone would end up becoming the theater for major power rivalry, with negative consequences outweighing possible economic gains.

The most startling feature in the recommendation is the exclusion of the USA from the list of countries with which to cooperate, notwithstanding the Independence Day message by the US Secretary of State which stated: “… our countries have developed a strong and mutually beneficial partnership built on the cornerstone of our people-to-people ties and shared democratic values. In the year ahead, we look forward to increasing trade and investment between our countries and strengthening our security cooperation to advance stability and prosperity throughout the Indo-Pacific region (NEWS, U.S. & Sri Lanka)

Such exclusions would inevitably result in the US imposing drastic tariffs to cripple Sri Lanka’s economy. Furthermore, the inclusion of India and China in the list of countries with whom Sri Lanka is to cooperate, ignores the objections raised by India about the presence of Chinese research vessels in Sri Lankan waters to the point that Sri Lanka was compelled to impose a moratorium on all such vessels.

CONCLUSION

During a panel discussion titled “Security Environment in the Indo-Pacific and Sri Lankan Diplomacy” supported by the Embassy of Japan, Prof. Ken Jimbo of Keio University, Japan emphasized that “… non-alignment today does not mean isolation”. Such an approach, he noted, requires the careful and strategic management of dependencies to preserve national autonomy while maintaining strategic international partnerships”. Perhaps Prof. Jimbo was not aware or made aware that Sri Lanka’s Foreign Policy is Neutral; a fact declared by successive Governments since 2019 and practiced by the current Government in the position taken in respect of the recent hostilities between India and Pakistan.

Although both Non-Alignment and Neutrality are often mistakenly used interchangeably, they both do NOT mean isolation. The difference is that Non-Alignment is NOT a Policy but only a Strategy, similar to Balancing, adopted by decolonized countries in the context of a by-polar world, while Neutrality is an Internationally recognised Rule Based Policy, with obligations to be observed by Neutral States and by the Community of Nations. However, Neutrality in today’s context of geopolitical rivalries resulting from the fluidity of changing dynamics offers greater protection in respect of security because it is Rule Based and strengthened by “the UN adoption of the Indian Ocean as a Zone of peace”, with the freedom to exercise its autonomy and engage with States in pursuit of its National Interests.

Apart from the positive comments “that the Indian Ocean should be regarded as a Zone of Peace” and that “from a defence perspective, Sri Lanka must remain neutral”, the second panelist, Professor of Oceanography at the University of Ruhuna, Terney Pradeep Kumara, also advocated that “from a Scientific and resource perspective (in the Exclusive Economic Zone) the country must remain active, given its location and the resources available in its maritime domain”. He went further and identified that Sri Lanka can work with countries such as India, China, Australia and South Africa.

For Sri Lanka to work together with India and China who already are geopolitical rivals made evident by the fact that India has already objected to the presence of China in the “Sea of Lanka”, questions the practicality of the suggestion. Furthermore, the fact that Prof. Kumara has excluded the US, notwithstanding the US Secretary of State’s expectations cited above, reflects unawareness of the geopolitical landscape in which the US, India and China are all actively known to search for minerals. In such a context, Sri Lanka should accept its limitations in respect of its lack of Diplomatic sophistication to “work with” such superpower rivals who are known to adopt unprecedented measures such as tariffs, if Sri Lanka is to avoid the fate of Milos during the Peloponnesian Wars.

Under the circumstances, it is in Sri Lanka’s best interest to lay aside its economic gains for security, and live by its proclaimed principles and policies of Neutrality and the concept of the Indian Ocean as a Zone of Peace by not permitting its EEC to be Explored and/or Exploited by anyone in its “maritime domain”. Since Sri Lanka is already blessed with minerals on land that is awaiting exploitation, participating in the extraction of minerals at the expense of security is not only imprudent but also an environmental contribution given the fact that the Sea and its resources is the Planet’s Last Frontier.

by Neville Ladduwahetty

Features

Protecting the ocean before it’s too late: What Sri Lankans think about deep seabed mining

Far beneath the waters surrounding Sri Lanka lies a largely unseen frontier, a deep seabed that may contain cobalt, nickel and rare earth elements essential to modern technologies, from smartphones to electric vehicles. Around the world, governments and corporations are accelerating efforts to tap these minerals, presenting deep-sea mining as the next chapter of the global “blue economy.”

For an island nation whose ocean territory far exceeds its landmass, the question is no longer abstract. Sri Lanka has already demonstrated its commitment to ocean governance by ratifying the United Nations High Seas Treaty (BBNJ Agreement) in September 2025, becoming one of the early countries to help trigger its entry into force. The treaty strengthens biodiversity conservation beyond national jurisdiction and promotes fair access to marine genetic resources.

Yet as interest grows in seabed minerals, a critical debate is emerging: Can Sri Lanka pursue deep-sea mining ambitions without compromising marine ecosystems, fisheries and long-term sustainability?

Speaking to The Island, Prof. Lahiru Udayanga, Dr. Menuka Udugama and Ms. Nethini Ganepola of the Department of Agribusiness Management, Faculty of Agriculture & Plantation Management, together with Sudarsha De Silva, Co-founder of EarthLanka Youth Network and Sri Lanka Hub Leader for the Sustainable Ocean Alliance, shared findings from their newly published research examining how Sri Lankans perceive deep-sea mineral extraction.

The study, published in the journal Sustainability and presented at the International Symposium on Disaster Resilience and Sustainable Development in Thailand, offers rare empirical insight into public attitudes toward deep-sea mining in Sri Lanka.

Limited Public Inclusion

“Our study shows that public inclusion in decision-making around deep-sea mining remains quite limited,” Ms. Nethini Ganepola told The Island. “Nearly three-quarters of respondents said the issue is rarely covered in the media or discussed in public forums. Many feel that decisions about marine resources are made mainly at higher political or institutional levels without adequate consultation.”

The nationwide survey, conducted across ten districts, used structured questionnaires combined with a Discrete Choice Experiment — a method widely applied in environmental economics to measure how people value trade-offs between development and conservation.

Ganepola noted that awareness of seabed mining remains low. However, once respondents were informed about potential impacts — including habitat destruction, sediment plumes, declining fish stocks and biodiversity loss — concern rose sharply.

“This suggests the problem is not a lack of public interest,” she told The Island. “It is a lack of accessible information and meaningful opportunities for participation.”

Ecology Before Extraction

Dr. Menuka Udugama said the research was inspired by Sri Lanka’s growing attention to seabed resources within the wider blue economy discourse — and by concern that extraction could carry long-lasting ecological and livelihood risks if safeguards are weak.

“Deep-sea mining is often presented as an economic opportunity because of global demand for critical minerals,” Dr. Udugama told The Island. “But scientific evidence on cumulative impacts and ecosystem recovery remains limited, especially for deep habitats that regenerate very slowly. For an island nation, this uncertainty matters.”

She stressed that marine ecosystems underpin fisheries, tourism and coastal well-being, meaning decisions taken about the seabed can have far-reaching consequences beyond the mining site itself.

Prof. Lahiru Udayanga echoed this concern.

“People tended to view deep-sea mining primarily through an environmental-risk lens rather than as a neutral industrial activity,” Prof. Udayanga told The Island. “Biodiversity loss was the most frequently identified concern, followed by physical damage to the seabed and long-term resource depletion.”

About two-thirds of respondents identified biodiversity loss as their greatest fear — a striking finding for an issue that many had only recently learned about.

A Measurable Value for Conservation

Perhaps the most significant finding was the public’s willingness to pay for protection.

“On average, households indicated a willingness to pay around LKR 3,532 per year to protect seabed ecosystems,” Prof. Udayanga told The Island. “From an economic perspective, that represents the social value people attach to marine conservation.”

The study’s advanced statistical analysis — using Conditional Logit and Random Parameter Logit models — confirmed strong and consistent support for policy options that reduce mineral extraction, limit environmental damage and strengthen monitoring and regulation.

The research also revealed demographic variations. Younger and more educated respondents expressed stronger pro-conservation preferences, while higher-income households were willing to contribute more financially.

At the same time, many respondents expressed concern that government agencies and the media have not done enough to raise awareness or enforce safeguards — indicating a trust gap that policymakers must address.

“Regulations and monitoring systems require social acceptance to be workable over time,” Dr. Udugama told The Island. “Understanding public perception strengthens accountability and clarifies the conditions under which deep-sea mining proposals would be evaluated.”

Youth and Community Engagement

Ganepola emphasised that engagement must begin with transparency and early consultation.

“Decisions about deep-sea mining should not remain limited to technical experts,” she told The Island. “Coastal communities — especially fishers — must be consulted from the beginning, as they are directly affected. Youth engagement is equally important because young people will inherit the long-term consequences of today’s decisions.”

She called for stronger media communication, public hearings, stakeholder workshops and greater integration of marine conservation into school and university curricula.

“Inclusive and transparent engagement will build trust and reduce conflict,” she said.

A Regional Milestone

Sudarsha De Silva described the study as a milestone for Sri Lanka and the wider Asian region.

“When you consider research publications on this topic in Asia, they are extremely limited,” De Silva told The Island. “This is one of the first comprehensive studies in Sri Lanka examining public perception of deep-sea mining. Organizations like the Sustainable Ocean Alliance stepping forward to collaborate with Sri Lankan academics is a great achievement.”

He also acknowledged the contribution of youth research assistants from EarthLanka — Malsha Keshani, Fathima Shamla and Sachini Wijebandara — for their support in executing the study.

A Defining Choice

As Sri Lanka charts its blue economy future, the message from citizens appears unmistakable.

Development is not rejected. But it must not come at the cost of irreversible ecological damage.

The ocean’s true wealth, respondents suggest, lies not merely in minerals beneath the seabed, but in the living systems above it — systems that sustain fisheries, tourism and coastal communities.

For policymakers weighing the promise of mineral wealth against ecological risk, the findings shared with The Island offer a clear signal: sustainable governance and biodiversity protection align more closely with public expectations than unchecked extraction.

In the end, protecting the ocean may prove to be not only an environmental responsibility — but the most prudent long-term investment Sri Lanka can make.

By Ifham Nizam

Features

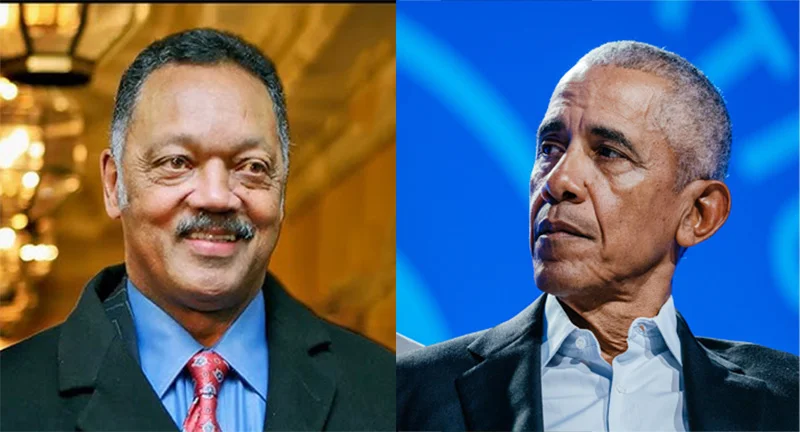

How Black Civil Rights leaders strengthen democracy in the US

On being elected US President in 2008, Barack Obama famously stated: ‘Change has come to America’. Considering the questions continuing to grow out of the status of minority rights in particular in the US, this declaration by the former US President could come to be seen as somewhat premature by some. However, there could be no doubt that the election of Barack Obama to the US presidency proved that democracy in the US is to a considerable degree inclusive and accommodating.

On being elected US President in 2008, Barack Obama famously stated: ‘Change has come to America’. Considering the questions continuing to grow out of the status of minority rights in particular in the US, this declaration by the former US President could come to be seen as somewhat premature by some. However, there could be no doubt that the election of Barack Obama to the US presidency proved that democracy in the US is to a considerable degree inclusive and accommodating.

If this were not so, Barack Obama, an Afro-American politician, would never have been elected President of the US. Obama was exceptionally capable, charismatic and eloquent but these qualities alone could not have paved the way for his victory. On careful reflection it could be said that the solid groundwork laid by indefatigable Black Civil Rights activists in the US of the likes of Martin Luther King (Jnr) and Jesse Jackson, who passed away just recently, went a great distance to enable Obama to come to power and that too for two terms. Obama is on record as owning to the profound influence these Civil Rights leaders had on his career.

The fact is that these Civil Rights activists and Obama himself spoke to the hearts and minds of most Americans and convinced them of the need for democratic inclusion in the US. They, in other words, made a convincing case for Black rights. Above all, their struggles were largely peaceful.

Their reasoning resonated well with the thinking sections of the US who saw them as subscribers to the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, for instance, which made a lucid case for mankind’s equal dignity. That is, ‘all human beings are equal in dignity.’

It may be recalled that Martin Luther King (Jnr.) famously declared: ‘I have a dream that one day this nation will rise up, live out the true meaning of its creed….We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal.’

Jesse Jackson vied unsuccessfully to be a Democratic Party presidential candidate twice but his energetic campaigns helped to raise public awareness about the injustices and material hardships suffered by the black community in particular. Obama, we now know, worked hard at grass roots level in the run-up to his election. This experience proved invaluable in his efforts to sensitize the public to the harsh realities of the depressed sections of US society.

Cynics are bound to retort on reading the foregoing that all the good work done by the political personalities in question has come to nought in the US; currently administered by Republican hard line President Donald Trump. Needless to say, minority communities are now no longer welcome in the US and migrants are coming to be seen as virtual outcasts who need to be ‘shown the door’ . All this seems to be happening in so short a while since the Democrats were voted out of office at the last presidential election.

However, the last US presidential election was not free of controversy and the lesson is far too easily forgotten that democratic development is a process that needs to be persisted with. In a vital sense it is ‘a journey’ that encounters huge ups and downs. More so why it must be judiciously steered and in the absence of such foresighted managing the democratic process could very well run aground and this misfortune is overtaking the US to a notable extent.

The onus is on the Democratic Party and other sections supportive of democracy to halt the US’ steady slide into authoritarianism and white supremacist rule. They would need to demonstrate the foresight, dexterity and resourcefulness of the Black leaders in focus. In the absence of such dynamic political activism, the steady decline of the US as a major democracy cannot be prevented.

From the foregoing some important foreign policy issues crop-up for the global South in particular. The US’ prowess as the ‘world’s mightiest democracy’ could be called in question at present but none could doubt the flexibility of its governance system. The system’s inclusivity and accommodative nature remains and the possibility could not be ruled out of the system throwing up another leader of the stature of Barack Obama who could to a great extent rally the US public behind him in the direction of democratic development. In the event of the latter happening, the US could come to experience a democratic rejuvenation.

The latter possibilities need to be borne in mind by politicians of the South in particular. The latter have come to inherit a legacy of Non-alignment and this will stand them in good stead; particularly if their countries are bankrupt and helpless, as is Sri Lanka’s lot currently. They cannot afford to take sides rigorously in the foreign relations sphere but Non-alignment should not come to mean for them an unreserved alliance with the major powers of the South, such as China. Nor could they come under the dictates of Russia. For, both these major powers that have been deferentially treated by the South over the decades are essentially authoritarian in nature and a blind tie-up with them would not be in the best interests of the South, going forward.

However, while the South should not ruffle its ties with the big powers of the South it would need to ensure that its ties with the democracies of the West in particular remain intact in a flourishing condition. This is what Non-alignment, correctly understood, advises.

Accordingly, considering the US’ democratic resilience and its intrinsic strengths, the South would do well to be on cordial terms with the US as well. A Black presidency in the US has after all proved that the US is not predestined, so to speak, to be a country for only the jingoistic whites. It could genuinely be an all-inclusive, accommodative democracy and by virtue of these characteristics could be an inspiration for the South.

However, political leaders of the South would need to consider their development options very judiciously. The ‘neo-liberal’ ideology of the West need not necessarily be adopted but central planning and equity could be brought to the forefront of their talks with Western financial institutions. Dexterity in diplomacy would prove vital.

-

Life style7 days ago

Life style7 days agoMarriot new GM Suranga

-

Business6 days ago

Business6 days agoMinistry of Brands to launch Sri Lanka’s first off-price retail destination

-

Features7 days ago

Features7 days agoMonks’ march, in America and Sri Lanka

-

Features7 days ago

Features7 days agoThe Rise of Takaichi

-

Features7 days ago

Features7 days agoWetlands of Sri Lanka:

-

News7 days ago

News7 days agoThailand to recruit 10,000 Lankans under new labour pact

-

Latest News1 day ago

Latest News1 day agoECB push back at Pakistan ‘shadow-ban’ reports ahead of Hundred auction

-

Latest News24 hours ago

Latest News24 hours agoTariffs ruling is major blow to Trump’s second-term agenda