Features

Moving up the CCS ladder, the 1915 riots and war service

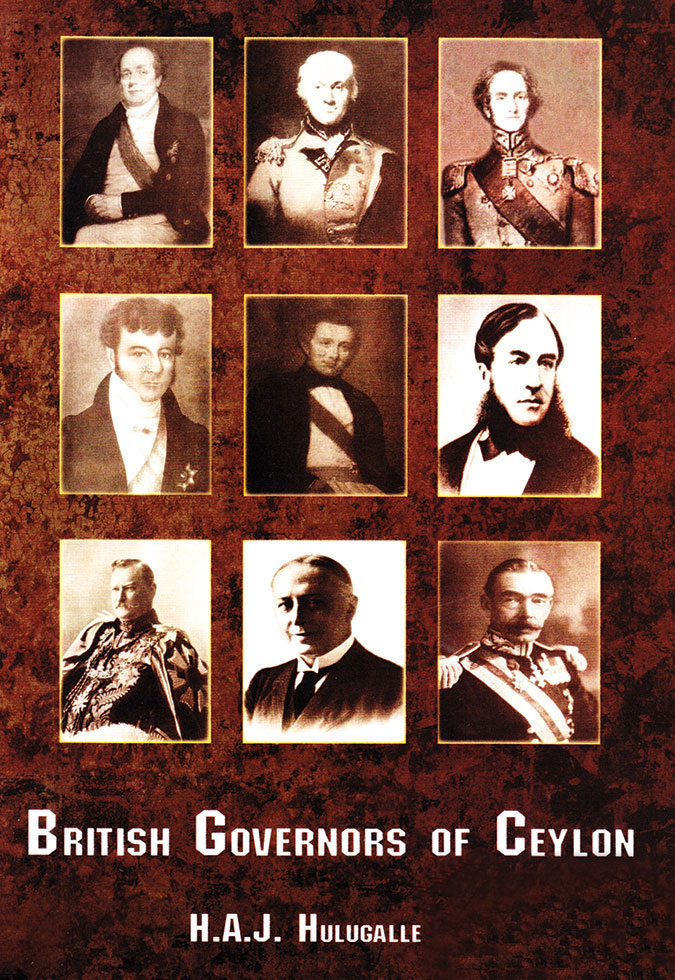

By Sir Henry Monck-Mason Moore,

last British Governor of Colonial Ceylon

Excerpted from HAJ Hulugalle’s British Governors of Ceylon

(Continued from last week)

On arrival in Ceylon in 1910 I was attached as a Cadet first to the Secretariat and then to the Colombo Kachcheri. Sir Henry McCallum was Governor, Sir Hugh Clifford, Colonial Secretary and Mr. E Bowes Principal Assistant Secretary. From such minute papers as came my way, it did not appear that Sir Henry and Sir Hugh were always at one in the views expressed.

Later, when in 1924 1 was posted to the Nigerian Secretariat, Sir Hugh Clifford was Governor and Sir Donald Cameron, Chief Secretary. They were a remarkable and highly gifted combination, both men of outstanding ability in their respective spheres. Sir Hugh was in my opinion quite the most outstanding personality under whom I have served despite his personal eccentricities of genius. It was a tragedy that they should have developed into a form of mental instability by the time he returned to Ceylon as Governor and then to Malaya. I will refer to this again later.

After my first year in Colombo I had been assured that I should remain in Jaffna for a year or more at least, and as stated earlier I had invited my sister to stay there with me. We were a happy party in the Jaffna Fort, which has been well described by Leonard Woolf in the second volume of his autobiography.It was much the same in my day. I also came to have a great respect and liking for the industry and sturdy independence of the Jaffna Tamil, and I was, therefore, very disappointed to have to leave it so soon to become an itinerating police magistrate up and down the Colombo-Kandy road. Before long I was back again in Colombo for a short spell as municipal magistrate, then to the Customs, finally as fourth Assistant in the Secretariat.

Colombo in the days of the Rubber Boom has in retrospect a very materialistic look. All communities were in a rush to get rich quick. Socially, wealth was the golden key to unlock the gate for the would-be social climber; and the Civil Service `caste’, as it had been described, could not compete, despite official prestige, with the Fort merchant princes. Up country. the planting industry was offering high prices for land which was disrupting the old aristocratic Kandyan feudal economy. while in Colombo the old caste distinctions in Sinhalese were becoming blurred by the wealth of a rapidly increasing middle class, which was also campaigning for a less paternal and more democratic form of government.

The Government and Assistant Government Agents in the Provinces and Districts were still left more or less undisturbed in the exercise of a paternal authority, and were genuinely interested in promoting the welfare and development of the local population with whom they were in close touch. Some viewed with reserve, not to say dismay, any attempt to bring political pressure upon them in the exercise of their duties.

Such an attitude is in no way peculiar to Ceylon. It is shared by the Civil Servants the world over, and as an old Civil Servant myself I have noted with regret the dissolution of the Ceylon Civil Service with a record over the years of which it had every right to be proud.

In 1914 with little or no warning Ceylon was overtaken by the War. At that time most believed it would be of short duration and unlikely to constitute any serious threat to British possessions East of Suez, though Ceylon was full of alarms and excursions so long as The Emden (a German cruiser) was at large. The Ceylon contingent of volunteers was quickly despatched to Egypt and the local volunteer regiments mobilized to defend our shores and in particular the Port of Colombo, which was the main port of call for Australian and New Zealand troops in transit to the battle fronts.

IV

At this time of crisis Sir Edward Stubbs, who had very recently arrived as Colonial Secretary, became acting Governor until such time as Chalmers (later Lord Chalmers) took over the administration. They were both men of great mental ability from the Home Civil Service, and had this in common that neither had had any previous Colonial experience. In the event, they were called upon to handle the delicate situation created by the 1915 Ceylon Riots before they had much time or opportunity to be in close personal touch with the different facets of Ceylonese public opinion of which the Morning Leader was the most forceful exponent.

Stubbs with his acid wit and somewhat gauche approach had no strong personal appeal, though his charming wife was soon deservedly popular. Chalmers seemed to be surrounded by a small circle with whom he could swap classical jokes or pursue his Sanskrit studies with scholarly members of the Buddhist priesthood. When the late Dr. Solomon Fernando died suddenly in the course of a political speech, the story, probably apochryphal was that he remarked on receipt of the news: I suppose the good doctor must have heard a still small voice saying to him ‘Fernando Po”‘.

With the benefit of hind sight it is easy to be wise after the event, but I am inclined to think it was a mistake to have declared Martial Law on the outbreak of the riots. It must be remembered that there was an atmosphere of war hysteria abroad which the mutiny of the Guides at Singapore had intensified.

The Attorney-General, Sir Anton Bertram, a fine lawyer and scholar, was a conscientious character, who could become jittery under pressure. He advised that as the Empire was at war, all Ceylonese could be regarded as “statutory camp followers” within the meaning of the Army Act, and as such amenable to trial by Court Martial. In effect this meant that the General Officer Commanding rather than the Governor became responsible for the maintenance of law and order, though the civil courts continued to function for less serious offences.

In the last resort the General confirmed the findings of the Court Martial though they were submitted to him through the Governor. General Malcolm, though a gallant soldier, had not the experience to fit him for the exercise of such a responsible task.

After the riots I was Secretary of the Commission of Enquiry into the action of the police, under the chairmanship of the Chief Justice, Sir Alexander Wood Renton. The Commission could find no positive evidence of conspiracy, though after the Singapore mutiny a few letters were found from Ceylonese in Singapore enquiring as to the local position. But in Ceylon itself the wildest rumours were circulating among the ignorant villagers suggesting that there was no longer any British Government.

The trouble started at Gampola with a Buddhist Wesak procession marching past the Mohammedan mosque, in which the Buddhists, were clearly the aggressors. As this was a trouble spot of long standing, action should have been taken by the local authorities to maintain order at the outset. This was not done and the trouble spread to Kandy, where the Police Magistrate and the Government Agent again failed to deal with the situation firmly and there was more rioting and shooting.

From Kandy it spread like a forest fire to Colombo and the coastal districts. A map of the affected areas showing the dates on which the riots broke out clearly indicated how it spread, and was suggestive that it was fanned, whether deliberately or not, by the rumours spread abroad. That the Buddhists, despite their non-violent creed, were the aggressors there can be no doubt.

After the sack of the Pettah I gained some notoriety in dealing with a vast crowd, that was trying to cross the bridge over the Kelaniya river to reinforce their fellow Sinhalese, who were supposed to have been massacred and raped by the Moors. In fact the exact opposite was the case. After long parleys with their leaders I had no alternative but to give the officer commanding about a dozen volunteers; whom I had hastily summoned to defend the bridge, the order to fire.

The first round was fired over their heads, but the crowd with cries of “his tuakuva” (empty guns) rushed to within about ten yards of us when they were dispersed by a volley which left one or two killed and a few wounded in their wake. Of actual numbers I have no record.

By this time I had been appointed an additional District judge for the Western Province and also a Special Commissioner under the Martial Law regulations with a few Punjabi soldiers to restore law and order in the area around Veyangoda, Heneratgoda and Minuwangoda. Mr. Fraser, the Government Agent of the Western Province, had obtained approval of a plan whereby the damage done to Moorish boutiques and property should be roughly assessed and the victims compensated by the payment of a collective fine imposed upon the Sinhalese villagers concerned.

Such a compulsory levy would, it was hoped, act as a deterrent to further rioting and at the’ same time provide speedy compensation for the losses sustained by its victims. If carried out as originally conceived the results might or might not have justified such emergency measures. But at the very last moment Fraser was told that the levy should be presented as a voluntary one, and that those reluctant to subscribe should be warned that, their properties would be assessed, and that it would therefore be to their financial advantage to make an immediate voluntary payment rather than wait till the necessary legislation was enacted.

I do not know who was responsible for this decision, but I suspect that Sir Anton Bertram was getting cold feet at the consequences of his Martial Law decision. The officers responsible for the collection of the levy were now presented with an almost impossible task which was a source of constant embarrassment.

It fell to my lot to prepare the dossier on which the Attorney General decided to bring a Mr. Bandaranaike for trial by Court Martial. Mr. Bandaranaike, an ardent Buddhist and temperance campaigner, became a convert to Christianity during his detention and there was much backstair missionary pressure to secure his, release. Eventually Mr. Eardley Norton came over from India to defend him, and secured his acquittal by the surprise production of an Indian tea maker, who provided an alibi.

By 1916 1 had had some five and a half years service and was granted my first leave on condition that I got a commission in the Army on arrival in England. I had been refused permission to join the Ceylon contingent in 1914. In London I found that direct, commissions were no longer given, so I enlisted as a gunner and driver in the Royal Horse Artillery.

After three month’s in the ranks I was gazetted a Lieutenant and sent for a month’s gunnery course at Shoeburyness. Eventually I joined a 60-pounder battery of the RGA. and volunteered to go as an officer reinforcement to Salonika, as my own battery was not yet ready to be sent to France. I was eventually invalided from the Struma Front with malaria, and after a short spell at home was posted to a battery in France in time for the final German defeat.

After the armistice we were 24 days in the saddle taking part in the triumphal advance and formed part of the army of occupation outside Cologne. Eventually I was demobilized and returned to Ceylon in August 1919. I was posted again to the Secretariat as Fourth Assistant Secretary to find Sir Graeme Thomson recently appointed as Colonial Secretary and Sir William Manning as Governor. He was an old friend of my future wife’s parents. He had been Inspector-General of the East African Rifles before his appointment, as Governor of Nyasaland, where his first wife had left him, so that both in Jamaica and on his first arrival in Ceylon, Government House was without an official hostess.

The Bensons, had stayed with him in Jamaica and after the war were invited to do so again in Colombo. Mrs. Benson and her daughter stayed on at Queen’s House for some time when Mr. Benson had to return to London where he was the Manager of the Johannesburg Consolidated Investment Coy. He had received a CBE. for his work with the Ministry of Munitions.

As a junior Secretariat officer I did not move in Queen’s House circles, but one morning I was exercising my polo pony before breakfast on the Galle Face green when a runaway horse came charging down with Miss Benson in the saddle. It was a big Hackney mare which Mr. Bawa, KC, had lent her, and I soon discovered that as the saddle had slipped and both bit and stirrups were maladjusted the mare was unmanageable.

So we changed mounts and I escorted her to the Garden Club for repairs. We were destined to see much of each other later, as she stayed on with Sir Graeme and Lady ‘Thomson for some weeks when he was acting Governor and I became his Private Secretary during Sir William Manning’s absence in London to discuss the Manning Constitution.

This was the subject of much deliberation in which the very able Attorney-General, Sir Henry Gollan, played a leading part. As Collins, later Sir Charles Collins, was seconded for special duty over its preparation, there was little or no record of it in the current Secretariat files, and I do not think that Sir Graeme, as a newcomer, played a very active part.

He had made his name during the war as Director of Admiralty Transport, and was referred to by Lloyd George as the greatest Transport expert since Noah. His services were rewarded by the promise of a Colonial Governorship, and when British Guiana became vacant he was offered and accepted the post.

In Ceylon he was much interested in the extension of the Railway from Anuradhapura to Trincomalee, which was carried out despite much initial opposition. His foresight was amply vindicated by the part it played in the Second World War. He was somewhat shy and reserved, sparing both of the spoken and written word, but deliberate in judgment and most kind and considerate. Lady Thomson had abounding energy and never spared herself in social work of all kinds in which she was deeply interested. Sir Graeme was a first class shot especially with a rifle and also a keen fisherman. My main recreation was to combine some form of shooting with his official circuits in the country side.

Sir William Manning, during his visit to London, met Miss Olga Sefton-Jones in Mr. and Mrs. Benson’s house in London. The Sefton-Jones’s were a Quaker family and friends of the Bensons. On the return of Sir William to Ceylon I was posted to Trincomalee as Assistant Government Agent. It was in many ways my most enjoyable post in Ceylon. I was responsible for the acquisition of all the land required for the Trincomalee railway station and the naval oil installations at China Bay. In addition there was the normal work of the Assistant Government Agent. The visits of the Admiral at Admiralty House and of the Navy when their ships came in for gunnery practice provided an agreeable interlude on return from a fortnight or more on circuit through the villages and village tanks of the countryside.

Features

Voting for new Pope set to begin with cardinals entering secret conclave

On Wednesday evening, under the domed ceiling of Michelangelo’s Sistine Chapel, 133 cardinals will vote to elect the Catholic Church’s 267th pope.

The day will begin at 10:00 (09:00 BST) with a mass in St Peter’s Basilica. The service, which will be televised, will be presided over by Giovanni Battista Re, the 91-year-old Cardinal Dean who was also the celebrant of Pope Francis’ funeral.

In the early afternoon, mobile signal within the territory of the Vatican will be deactivated to prevent anyone taking part in the conclave from contacting the outside world.

Around 16:15 (15:15 BST), the 133 cardinal electors will gather in the Pauline Chapel and form a procession to the Sistine Chapel.

Once in the Sistine Chapel, one hand resting on a copy of the Gospel, the cardinals will pronounce the prescribed oath of secrecy which precludes them from ever sharing details about how the new Pope was elected.

When the last of the electors has taken the oath, a meditation will be held. Then, the Master of Pontifical Liturgical Celebrations Diego Ravelli will announce “extra omnes” (“everybody out”).

He is one of three ecclesiastical staff allowed to stay in the Sistine Chapel despite not being a cardinal elector, even though they will have to leave the premises during the counting of the votes.

The moment “extra omnes” is pronounced marks the start of the cardinals’ isolation – and the start of the conclave.

The word, which comes from the Latin for “cum clave”, or “locked with key” is slightly misleading, as the cardinals are no longer locked inside; rather, on Tuesday Vatican officials closed the entrances to the Apostolic Palace – which includes the Sistine Chapel- with lead seals which will remain until the end of the proceedings. Swiss guards will also flank all the entrances to the chapel.

Diego Ravelli will distribute ballot papers, and the cardinals will proceed to the first vote soon after.

While nothing forbids the Pope from being elected with the first vote, it has not happened in centuries. Still, that first ballot is very important, says Austen Ivereigh, a Catholic writer and commentator.

“The cardinals who have more than 20 votes will be taken into consideration. In the first ballot the votes will be very scattered and the electors know they have to concentrate on the ones that have numbers,” says Ivereigh.

He adds that every other ballot thereafter will indicate which of the cardinals have the momentum. “It’s almost like a political campaign… but it’s not really a competition; it’s an effort by the body to find consensus.”

If the vote doesn’t yield the two-third majority needed to elect the new pope, the cardinals go back to guesthouse Casa Santa Marta for dinner. It is then, on the sidelines of the voting process, that important conversations among the cardinals take place and consensus begins to coalesce around different names.

According to Italian media, the menu options consist of light dishes which are usually served to guests of the residence, and includes wine – but no spirits. The waiters and kitchen staff are also sworn to secrecy and cannot leave the grounds for the duration of the conclave.

From Thursday morning, cardinals will be taking breakfast between 06:30 (05:30 BST) and 07:30 (06:30 BST) ahead of mass at 08:15 (07:15 BST). Two votes then take place in the morning, followed by lunch and rest. In his memoirs, Pope Francis said that was when he began to receive signals from the other cardinals that serious consensus was beginning to form around him; he was elected during the first afternoon vote. The last two conclaves have all concluded by the end of the second day.

There is no way of knowing at this stage whether this will be a long or a short conclave – but cardinals are aware that dragging the proceedings on could be interpreted as a sign of gaping disagreements.

As they discuss, pray and vote, outside the boarded-up windows of the Sistine Chapel thousands of faithful will be looking up to the chimney to the right of St Peter’s Basilica, waiting for the white plume of smoke to signal that the next pope has been elected.

[BBC]

Features

Beyond Left and Right: From Populism to Pragmatism and Recalibrating Democracy

The world is going through a political shake-up. Everywhere you look—from Western democracies to South Asian nations—people are choosing leaders and parties that seem to clash in ideology. One moment, a country swings left, voting for progressive policies and climate action. The next, a neighbouring country rushes into the arms of right-wing populism, talking about nationalism and tradition.

It’s not just puzzling—it’s historic. This global tug of war between opposing political ideas is unlike anything we’ve seen in recent decades. In this piece, I explore this wave of political contradictions, from the rise of labour movements in Australia and Canada, to the continued strength of conservative politics in the US and India, and finally to the surprising emergence of a radical leftist party in Sri Lanka.

Australia and Canada: A Comeback for Progressive Politics

Australia recently voted in the Labour Party, with Anthony Albanese becoming Prime Minister after years of conservative rule under Scott Morrison. Albanese brought with him promises of fairer wages, better healthcare, real action on climate change, and closing the inequality gap. For many Australians, it was a fresh start—a turn away from business-as usual politics.

In Canada, a political shift is unfolding with the rise of The Right Honourable Mark Carney, who became Prime Minister in March 2025, after leading the Liberal Party. Meanwhile, Jagmeet Singh and the New Democratic Party (NDP) are gaining traction with their progressive agenda, advocating for enhanced social safety nets in healthcare and housing to address growing frustrations with rising living costs and a strained healthcare system..

But let’s be clear—this isn’t a return to old-school socialism. Instead, voters seem to be leaning toward practical, social-democratic ideas—ones that offer government support without fully rejecting capitalism. People are simply fed up with policies that favour the rich while ignoring the struggles of everyday families. They’re calling for fairness, not radicalism.

America’s Rightward Drift: The Trump Effect Still Lingers

In contrast, the political story in the United States tells a very different tale. Even after Donald Trump left office in 2020, the Republican Party remains incredibly powerful—and popular.

Trump didn’t win hearts through traditional conservative ideas. Instead, he tapped into a raw frustration brewing among working-class Americans. He spoke about lost factory jobs, unfair trade deals, and an elite political class that seemed disconnected from ordinary life. His messages about “America First” and restoring national pride struck a chord—especially in regions hit hard by globalisation and automation.

Despite scandals and strong opposition, Trump’s brand of politics—nationalist, anti-immigration, and skeptical of global cooperation—continues to dominate the Republican Party. In fact, many voters still see him as someone who “tells it like it is,” even if they don’t agree with everything he says.

It’s a sign of a deeper trend: In the US, cultural identity and economic insecurity have merged, creating a political environment where conservative populism feels like the only answer to many.

India’s Strongman Politics: The Modi Era Continues

Half a world away, India is witnessing its own version of populism under Prime Minister Narendra Modi. His party—the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP)—has ruled with a blend of Hindu nationalism, economic ambition, and strong leadership.

Modi is incredibly popular. His supporters praise his development projects, digital push, and efforts to raise India’s profile on the global stage. But critics argue that his leadership is dividing the country along religious lines and weakening its long-standing secular values.

Still, for many Indians—especially the younger generation and the rural poor—Modi represents hope, strength, and pride. They see him as someone who has delivered where previous leaders failed. Whether it’s building roads, providing gas connections to villages, or cleaning up bureaucracy, the BJP’s strong-arm tactics have resonated with large sections of the population.

India’s political direction shows how nationalism can be powerful—especially when combined with promises of economic progress and security.

A Marxist Comeback? Sri Lanka’s Political Wild Card

Then there’s Sri Lanka—a country in crisis, where politics have taken a shocking turn.

For decades, Sri Lanka was governed by familiar faces and powerful families. But after years of financial mismanagement, corruption, and a devastating economic collapse, public trust in mainstream parties has plummeted. Into this void stepped a party many thought had been sidelined for good—the Janatha Vimukthi Peramuna (JVP), a Marxist-Leninist group with a history of revolutionary roots.

Once seen as radical and even dangerous, the JVP has rebranded itself as a disciplined, modern political force. Today, it speaks directly to the country’s suffering masses: those without jobs, struggling to buy food, and fed up with elite corruption.

The party talks about fair wealth distribution, workers’ rights, and standing up to foreign economic pressures. While their ideas are left-leaning, their growing support is driven more by public frustration with current political leaders than by any shift toward Marxism by the public or any move away from it by the JVP.

Sri Lanka’s case is unique—but not isolated. Across the world, when economies collapse and inequality soars, people often turn to ideologies that offer hope and accountability—even if they once seemed extreme.

A Global Puzzle: Why Are Politics So Contradictory Now?

So what’s really going on? Why are some countries swinging left while others turn right?

The answer lies in the global crises and rapid changes of the past two decades. The 2008 financial crash, worsening inequality, mass migrations, terrorism fears, the COVID-19 pandemic, and now climate change have all shaken public trust in traditional politics.

Voters everywhere are asking the same questions: Who will protect my job? Who will fix healthcare? Who will keep us safe? The answers they choose depend not just on ideology, but on their unique national experiences and frustrations.

In countries where people feel abandoned by global capitalism, they may choose left-leaning parties that promise welfare and fairness. In others, where cultural values or national identity feel under threat, right-wing populism becomes the answer.

And then there’s the digital revolution. Social media has turbocharged political messaging. Platforms like Twitter, Facebook, and YouTube allow both left and right movements to reach people directly—bypassing traditional media. While this has given power to progressive youth movements, it’s also allowed misinformation and extremist views to flourish, deepening polarisation.

Singapore: The Legacy of Pragmatic Leadership and Technocratic Governance

Singapore stands as a unique case in the global political landscape, embodying a model of governance that blends authoritarian efficiency with capitalist pragmatism. The country’s political identity has been shaped largely by its founding Prime Minister, Lee Kuan Yew, often regarded as a political legend for transforming a resource-poor island into one of the most prosperous and stable nations in the world. His brand of leadership—marked by a strong central government, zero tolerance for corruption, and a focus on meritocracy—has continued to influence Singapore’s political ideology even after his passing. The ruling People’s Action Party (PAP), which has been in power since independence, remains dominant, but it has had to adapt to a new generation of voters demanding more openness, transparency, and participatory governance.

Despite criticisms of limited political pluralism, Singapore’s model is often admired for its long-term planning, public sector efficiency, and ability to balance rapid economic development with social harmony. In an era of rising populism and political fragmentation elsewhere, Singapore’s consistent technocratic approach provides a compelling counter-narrative—one that prioritises stability, strategic foresight, and national cohesion over ideological extremes.

What the Future Holds

We are living in a time where political boundaries are blurring, and old labels don’t always fit. Left and right are no longer clear-cut. Populists can be socialist or ultra-conservative. Liberals may support strong borders. Conservatives may promote welfare if it wins votes.

What matters now is trust—people are voting for those who seem to understand their pain, not just those with polished manifestos.

As economic instability continues and global challenges multiply, this ideological tug-of-war is likely to intensify. Whether we see more progressive reforms or stronger nationalist movements will depend on how well political leaders can address real issues, from food security to climate disasters.

One thing is clear: the global political wave is still rising. And it’s carrying countries in very different directions.

Conclusion

The current wave of global political ideology is defined by its contradictions, complexity, and context-specific transformations. While some nations are experiencing a resurgence of progressive, left-leaning movements—such as Australia’s Labour Party, Canada’s New Democratic Party, and Sri Lanka’s Marxist-rooted JVP—others are gravitating toward right-wing populism, nationalist narratives, and conservative ideologies, as seen in the continued strength of the US Republican Party and the dominant rule of Narendra Modi’s BJP in India. Amid this ideological tug-of-war, Singapore presents a unique political model. Eschewing populist swings, it has adhered to a technocratic, pragmatic form of governance rooted in the legacy of Lee Kuan Yew, whose leadership transformed a struggling post-colonial state into a globally admired economic powerhouse. Singapore’s emphasis on strategic planning, meritocracy, and incorruptibility provides a compelling contrast to the ideological turbulence in many democracies.

What ties these divergent trends together is a common undercurrent of discontent with traditional politics, growing inequality, and the digital revolution’s impact on public discourse. Voters across the world are searching for leaders and ideologies that promise clarity, security, and opportunity amid uncertainty. In mature democracies, this search has split into dual pathways—either toward progressive reform or nostalgic nationalism. In emerging economies, political shifts are even more fluid, influenced by economic distress, youth activism, and demands for institutional change.

Ultimately, the world is witnessing not a single ideological revolution, but a series of parallel recalibrations. These shifts do not point to the triumph of one ideology over another, but rather to the growing necessity for adaptive, responsive, and inclusive governance. Whether through leftist reforms, right-wing populism, or technocratic stability like Singapore’s, political systems will increasingly be judged not by their ideological purity but by their ability to address real-world challenges, unite diverse populations, and deliver tangible outcomes for citizens. In that respect, the global political wave is not simply a matter of left vs. right—it is a test of resilience, innovation, and leadership in a rapidly evolving world.

(The writer, a senior Chartered Accountant and professional banker, is Professor at SLIIT , Malabe. He is also the author of the “Doing Social Research and Publishing Results”, a Springer publication (Singapore), and “Samaja Gaveshakaya (in Sinhala). The views and opinions expressed in this article are solely those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the institution he works for. He can be contacted at saliya.a@slit.lk and www.researcher.com)

Features

An opportunity to move from promises to results

The local government elections, long delayed and much anticipated, are shaping up to be a landmark political event. These elections were originally due in 2023, but were postponed by the previous government of President Ranil Wickremesinghe. The government of the day even defied a Supreme Court ruling mandating that elections be held without delay. They may have feared a defeat would erode that government’s already weak legitimacy, with the president having assumed office through a parliamentary vote rather than a direct electoral mandate following the mass protests that forced the previous president and his government to resign. The outcome of the local government elections that are taking place at present will be especially important to the NPP government as it is being accused by its critics of non-delivery of election promises.

Examples cited are failure to bring opposition leaders accused of large scale corruption and impunity to book, failure to bring a halt to corruption in government departments where corruption is known to be deep rooted, failure to find the culprits behind the Easter bombing and failure to repeal draconian laws such as the Prevention of Terrorism Act. In the former war zones of the north and east, there is also a feeling that the government is dragging its feet on resolving the problem of missing persons, those imprisoned without trial for long periods and return of land taken over by the military. But more recently, a new issue has entered the scene, with the government stating that a total of nearly 6000 acres of land in the northern province will be declared as state land if no claims regarding private ownership are received within three months.

The declaration on land to be taken over in three months is seen as an unsympathetic action by the government with an unrealistic time frame when the land in question has been held for over 30 years under military occupation and to which people had no access. Further the unclaimed land to be designated as “state land” raises questions about the motive of the circular. It has undermined the government’s election campaign in the North and East. High-level visits by the President, Prime Minister, and cabinet ministers to these regions during a local government campaign were unprecedented. This outreach has signalled both political intent and strategic calculation as a win here would confirm the government’s cross-ethnic appeal by offering a credible vision of inclusive development and reconciliation. It also aims to show the international community that Sri Lanka’s unity is not merely imposed from above but affirmed democratically from below.

Economic Incentives

In the North and East, the government faces resistance from Tamil nationalist parties. Many of these parties have taken a hardline position, urging voters not to support the ruling coalition under any circumstances. In some cases, they have gone so far as to encourage tactical voting for rival Tamil parties to block any ruling party gains. These parties argue that the government has failed to deliver on key issues, such as justice for missing persons, return of military-occupied land, release of long-term Tamil prisoners, and protection against Buddhist encroachment on historically Tamil and Muslim lands. They make the point that, while economic development is important, it cannot substitute for genuine political autonomy and self-determination. The failure of the government to resolve a land issue in the north, where a Buddhist temple has been put up on private land has been highlighted as reflecting the government’s deference to majority ethnic sentiment.

The problem for the Tamil political parties is that these same parties are themselves fractured, divided by personal rivalries and an inability to form a united front. They continue to base their appeal on Tamil nationalism, without offering concrete proposals for governance or development. This lack of unity and positive agenda may open the door for the ruling party to present itself as a credible alternative, particularly to younger and economically disenfranchised voters. Generational shifts are also at play. A younger electorate, less interested in the narratives of the past, may be more open to evaluating candidates based on performance, transparency, and opportunity—criteria that favour the ruling party’s approach. Its mayoral candidate for Jaffna is a highly regarded and young university academic with a planning background who has presented a five year plan for the development of Jaffna.

There is also a pragmatic calculation that voters may make, that electing ruling party candidates to local councils could result in greater access to state funds and faster infrastructure development. President Dissanayake has already stated that government support for local bodies will depend on their transparency and efficiency, an implicit suggestion that opposition-led councils may face greater scrutiny and funding delays. The president’s remarks that the government will find it more difficult to pass funds to local government authorities that are under opposition control has been heavily criticized by opposition parties as an unfair election ploy. But it would also cause voters to think twice before voting for the opposition.

Broader Vision

The government’s Marxist-oriented political ideology would tend to see reconciliation in terms of structural equity and economic justice. It will also not be focused on ethno-religious identity which is to be seen in its advocacy for a unified state where all citizens are treated equally. If the government wins in the North and East, it will strengthen its case that its approach to reconciliation grounded in equity rather than ethnicity has received a democratic endorsement. But this will not negate the need to address issues like land restitution and transitional justice issues of dealing with the past violations of human rights and truth-seeking, accountability, and reparations in regard to them. A victory would allow the government to act with greater confidence on these fronts, including possibly holding the long-postponed provincial council elections.

As the government is facing international pressure especially from India but also from the Western countries to hold the long postponed provincial council elections, a government victory at the local government elections may speed up the provincial council elections. The provincial councils were once seen as the pathway to greater autonomy; their restoration could help assuage Tamil concerns, especially if paired with initiating a broader dialogue on power-sharing mechanisms that do not rely solely on the 13th Amendment framework. The government will wish to capitalize on the winning momentum of the present. Past governments have either lacked the will, the legitimacy, or the coordination across government tiers to push through meaningful change.

Obtaining the good will of the international community, especially those countries with which Sri Lanka does a lot of economic trade and obtains aid, India and the EU being prominent amongst these, could make holding the provincial council elections without further delay a political imperative. If the government is successful at those elections as well, it will have control of all three tiers of government which would give it an unprecedented opportunity to use its 2/3 majority in parliament to change the laws and constitution to remake the country and deliver the system change that the people elected it to bring about. A strong performance will reaffirm the government’s mandate and enable it to move from promises to results, which it will need to do soon as mandates need to be worked at to be long lasting.

by Jehan Perera

-

News6 days ago

News6 days agoRanil’s Chief Security Officer transferred to KKS

-

Opinion4 days ago

Opinion4 days agoRemembering Dr. Samuel Mathew: A Heart that Healed Countless Lives

-

Business2 days ago

Business2 days agoAitken Spence Travels continues its leadership as the only Travelife-Certified DMC in Sri Lanka

-

Features7 days ago

Features7 days agoThe Broken Promise of the Lankan Cinema: Asoka & Swarna’s Thrilling-Melodrama – Part IV

-

News7 days ago

News7 days agoRadisson Blu Hotel, Galadari Colombo appoints Marko Janssen as General Manager

-

Business6 days ago

Business6 days agoCCPI in April 2025 signals a further easing of deflationary conditions

-

Features7 days ago

Features7 days agoA piece of home at Sri Lankan Musical Night in Dubai

-

Features6 days ago

Features6 days agoExpensive to die; worship fervour eclipses piety