Features

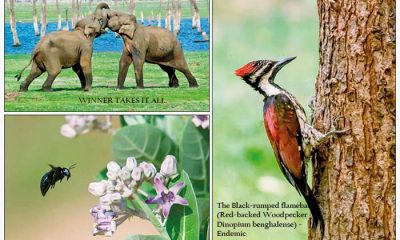

More on Wilpattu, natural systems and exotic flora

Excerpted from the authorized biography of Thilo Hoffmann

by Douglas B. Ranasinghe

During the years that followed 1985, the Park was closed and abandoned. Animals in it were slaughtered, especially buffaloes, wild pig, sambhur and deer. All the visitors’ and staff bungalows were ransacked and largely destroyed by roaming poachers, criminals and timber thieves.

In 2005 the Park was reopened, with a hardworking Park Warden, Wasantha Pushpananda. At his request and the urging of Geepal Fernando, Thilo spent nearly two million rupees on the reconstruction of the Talawila bungalow, in memory of his wife.

Only two years later the Park was again abandoned with the re-emergence of incursions from surrounding areas. Warden Pushpananda was killed. Again wildlife was depleted, and the re-built bungalows ransacked. After the fall of the LTTE, the Park was opened for visitors again in 2010. Once more, Thilo restored the bungalow.But pressure to open the coastal tract for through-traffic to Mannar persists. An easy alternative from Nochchiyagama via Nikawewa and Tantirimalai to Cheddikulam is ignored.

While this was being written, certain authorities have illegally and arbitrarily cut a new road along the coast within Wilpattu, and developed and opened for public use the Army road, damaging the ecology of the National Park on an unprecedented scale. The matter is being contested in court. Several conservation bodies, including the WNPS and Ceylon Bird Club – Thilo’s roles in these are described later – have been battling to uphold the law and save the Park. At their initial meeting and first press conference Thilo, now retired and in Sri Lanka for an annual stay of several months, was an invited speaker.

Natural systems and exotic flora

A `patana’ (sometimes anglicized as ‘patna’) is a grassland of Sri Lanka in the hills or mountains without trees or shrubs but typically intersected by sholas, described below. A `talawa’ is a savanna-type grassland with trees or groups of trees spaced some distance apart; these are mostly fire-resistant species. (Both are traditional Sri Lankan terms).

The afforestation of patanas and talawas with the exotic Pinus caribaea trees was a major point of contention between Thilo, representing the WNPS, and the Forest Department (the ‘FD’).

The FD claims that both patanas and talawas are man made systems whose lands had originally been under forest. Thus they misname the establishment of sterile pinus or eucalyptus plantations as “re-afforestation”. One Conservator of Forests had even proposed the “re-afforestation” of the open plains in the National Parks of the Yala complex, on the same reasoning. Thilo observes:

“When the advocates of pinus claim that under it indigenous species can freely develop, they think of infillings and plantings in degraded wet zone forests, e.g. around Sinharaja. Consider the biological (floral and faunal) composition of ‘dry patanas’ and talawas, and the indisputable fact that in both systems plants and other living organisms have evolved which are confined to these systems as their exclusive habitat.

“One example is the daffodil orchid (Ipsea speciosa) which is endemic to the patanas. It takes a very long time for a species to evolve and establish itself, wherefore the presence of endemics in a system is a strong indication that it is natural and not man-made. The existence of sholas also tends to support this view. It can further be assumed that prehistoric man at the relevant time had neither the means nor the need to clear such large areas permanently.

“By establishing the alien monocultures the FD has practically destroyed climax-type natural systems which only 50 years ago and for at least one hundred thousand years before have characterized the hill country, especially the Uva Plateau and the adjoining foothills.”

Against strong majority opinion, Thilo thus maintains that patanas, typically with sholas (see below), are a natural system, considering other factors, too, such as climate, soil conditions, exposure and topography – not man-made, although during the last three centuries selected patanas were seasonally burnt by the few thinly-spread inhabitants of the area.

Today there are few remnants of typical patanas and none of any sizeable extent. During the last half century patanas have been degraded and destroyed not only by the Forest Department but also through systematic State-sponsored settlement and the subsequent opening for cultivation of even the steepest slopes. The State has failed to recognize and appreciate patanas as a national system of value and to protect at least one typical and sufficiently large extent of these original grasslands. Patanas covered about 160,000 acres or 250 square miles (650 square km) of land, mainly in Uva.

Thilo condemns the establishment of pinus plantations not only because these destroy such natural systems and diversity but also for aesthetic reasons. He explains:

“There are no conifers native to Sri Lanka. Any plant belonging to the family with needles instead of leaves is a ‘double alien’ also because of its utterly out-of-place appearance in our scenery and environment. Pinus plantations alter the landscape massively – dark, nearly black, brooding patches in an otherwise bright and pleasant world.

“These are alien monocultures which exterminate the rich fauna and flora of the patanas and talawas. They might well be characterized as ‘man-propagated invasive foreign flora’, a term which has recently been much talked and written about. [See below.]”

Another important fact was overlooked, and seems to be largely unknown. Thilo points out that healthy, natural Sri Lankan forests do not catch fire even under extreme conditions. In order to clear the land the vegetation consisting of trees and undergrowth has to be felled and at least partly dried before a fire can be started.

Decades ago when he was traveling at night in the dry zone during the annual drought, dozens of chena plots would be ablaze, the fire having being fanned by the strong kachan wind. But when it was over, and only white ash remained, the surrounding forest at the very edge of the clearing was hardly singed, the fire being unable to spread.

On the other hand, pinus plantations, which are supposed to “re-afforest” the patanas, burn out easily and completely due to their resinous nature. All too often this happens. Thilo remembers this unique region as it was in his early years:

“In the late forties and the fifties of the last century the Uva Basin was very thinly populated. Traditional ways of life prevailed in much of the Uva Province; pack bulls were yet a common sight in its remoter parts.

“In the Uva Basin, large tracts of open patana covered most of the undulating area, with villages and paddy lands confined to and hidden in the river valleys. These patanas were then the main habitat of the painted partridge which is now restricted to a small area near Bibile. The endemic daffodil orchid was present in most of the Uva patanas, including those at Chelsea Estate and along the road from Bandarawela to Welimada.

“There were no forests except the so-called sholas, which are narrow strips of forest along the small water courses that have cut their way into the hillsides. These sholas are rich systems with many plant species and animals. Muntjac, mouse deer, pangolin, porcupine, hare and a great variety of birds found suitable habitats in them. Where patana and forest meet the dividing line is sharp, clearly defined and permanent; there is no “creeping” of the forest or shola in to the patana grasslands.”

(‘Shola’ is a word of Indian origin. With regard to the Uva plateau see also Thilo’s description in W.W.A. Phillips’s Handbook of the Mammals of Ceylon, Second edition, 1980.)

Early in the last century Bella Sidney Woolf, sister of Leonard, in her book How to See Ceylon aptly describes the Uva Plateau as “one of the great open spaces of the world that gives one a sense of freedom”. G. M. Henry, the ornithologist, who was active in Ceylon up to the middle of the last century refers to “the great Uva patna basin” in his publications. Today it is as cluttered up as most parts of Sri Lanka. Thilo says:

“At that time sholas were also present in many tea estates and were protected by law as stream reservations. Plantation managements strictly maintained these reservations, not only ensuring a high biodiversity in the hillsides, but also a regular supply of clean water for the villages in the valleys below and for their paddy fields.

“Later, as the political situation in Colombo changed and the population increased, these very useful and progressive reservations were gradually encroached upon and cleared by villagers and eventually disappeared, many being finally ‘regularized’ i.e. officially given to the illegal occupants.

“The result in many cases was scarcity of water in the villages, and often landslides. In the mid 20th century there were practically no landslides in Uva; today they occur regularly. The state then did nothing at all to enforce the law on these stream reservations, which still exists as a ‘dead letter’.

“Soon the Government also decided to settle people in the large extents of patana State land in Uva, and the Forest Department began to establish on the grassy slopes monoculture plantations of eucalyptus and pinus species. First as a trial at Palugama (now Keppetipola), and then on a large scale on every hillside in the area, they planted these exotic trees on the basis that the grasslands had originally been forest. These activities radically changed the character of the Uva Plateau, and today it bears no comparison to what it was in the 1930s to 1950s and historically.”

As an agronomist Thilo had soon noted that the soils of patana lands are shallow, gravelly, excessively drained, and very erodable if cleared of the original vegetation, especially the steep hillsides. The continuing clearing of such land is the opposite of development, and it has caused untold harm to the areas concerned.

Similarly, Thilo and the WNPS were not happy about the establishment of extensive teak and eucalyptus plantations in the dry zone where large extents of indigenous forest were cleared for the purpose.

In the intermediate and wet zone Thilo advocated afforestation with mixed mahogany and jak trees. This had been done during the Second World War when State forest was given out to private enterprise for the growing of papaya. He explains:

“This was for the production of papain, then a valuable export commodity in worldwide short supply during the war. The planting of the other trees together with the commercial crop was a condition. These mixed plantations allow the development of indigenous species amongst the jak and mahogany. They have formed marvellous and majestic forests, and now yield valuable timber. They can be seen where the Kurunegala-Dambulla road passes through two of them, and also in many other locations.

The growing of teak in the right places is undoubtedly justified, but generally suitable indigenous trees should be preferred even for the commercial production of timber. The Forest Department seems to have a predilection for exotics, as in the Knuckles, which often are as easy to grow as weeds, like pinus, and thus preferred. Thilo observes:

“On the other hand, repeated efforts are being made to eradicate so-called invasive exotic species. Most such campaigns are not only futile but extremely costly, as in the case of the Lantana (gandapana or katu hinguru) plant. This was introduced to Ceylon nearly 200 years ago as an ornamental plant and is a weed only in neglected and waste lands, e.g. chenas. Lantana takes over where man has destroyed the natural vegetation, and under its protective cover and shade native trees can re-emerge over long periods.

“The most harmful invasive plants in Sri Lanka are aquatic species such as the water hyacinth and salvinia. Others become harmful only where the natural system and order have been disturbed. Some of the plants listed as invasive are indeed a threat to the existing ecosystems, such as the untidy Eurium odoratum (podisingho maram) and Prosopispato is julfliora, which is spreading like wildfire in the Bundala area and elsewhere.

“Others are long established and have found niches without causing harm, such as Opuntia stricta, Clusia rosea or even the pretty gorse which has existed in the Nuwara Eliya area for one-and a-quarter centuries. It found its way to the Horton Plains only in the wake of massive visitation. With minimal attention it could have been kept in check, which is also the case with black wattle (Acacia mollissima) that has spread in from neighbouring tea fields.”

Cloud forests

Cloud forest is tropical mountain forest shrouded in cloud for much of the year, with short trees, rich in epiphytes. In the last quarter of the last century Thilo Hoffmann and a few other observers noted and commented on a strange and disturbing phenomenon in the hill country. The cloud forests of Sri Lanka, it appeared, were dying.

It was Hoffmann who did most to draw attention to the matter, and to analyze it carefully. This he did mostly in reports and papers appearing in Loris’ and the Ceylon Bird Club Notes’. Diligent observations across half a century of the Horton Plains placed him in a unique position to discern the changes.

An article by him submitted in 2005 to Loris is reproduced as Appendix II. There, as before, he attributes the damage to air pollution, and also proposes a remedy in the form of a plan to control it. In the text, as published by Loris, certain critical remarks are omitted and there are some distortions, hence the original script is given here.

In November 2006 Hoffmann observed possible signs of recovery of the cloud forest, apparently the first time this was recorded. He confirmed the recovery during subsequent visits and reported on it in more detail in 2009′.

Shortly before the publication of the present book, according to a newspaper report, a research team of the University of Sabaragamuwa had also come to the conclusion that the decline of cloud forests was due to air pollution.

Features

Crucial test for religious and ethnic harmony in Bangladesh

Will the Bangladesh parliamentary election bring into being a government that will ensure ethnic and religious harmony in the country? This is the poser on the lips of peace-loving sections in Bangladesh and a principal concern of those outside who mean the country well.

Will the Bangladesh parliamentary election bring into being a government that will ensure ethnic and religious harmony in the country? This is the poser on the lips of peace-loving sections in Bangladesh and a principal concern of those outside who mean the country well.

The apprehensions are mainly on the part of religious and ethnic minorities. The parliamentary poll of February 12th is expected to bring into existence a government headed by the Bangladesh Nationalist Party (BNP) and the Islamist oriented Jamaat-e-Islami party and this is where the rub is. If these parties win, will it be a case of Bangladesh sliding in the direction of a theocracy or a state where majoritarian chauvinism thrives?

Chief of the Jamaat, Shafiqur Rahman, who was interviewed by sections of the international media recently said that there is no need for minority groups in Bangladesh to have the above fears. He assured, essentially, that the state that will come into being will be equable and inclusive. May it be so, is likely to be the wish of those who cherish a tension-free Bangladesh.

The party that could have posed a challenge to the above parties, the Awami League Party of former Prime Minister Hasina Wased, is out of the running on account of a suspension that was imposed on it by the authorities and the mentioned majoritarian-oriented parties are expected to have it easy at the polls.

A positive that has emerged against the backdrop of the poll is that most ordinary people in Bangladesh, be they Muslim or Hindu, are for communal and religious harmony and it is hoped that this sentiment will strongly prevail, going ahead. Interestingly, most of them were of the view, when interviewed, that it was the politicians who sowed the seeds of discord in the country and this viewpoint is widely shared by publics all over the region in respect of the politicians of their countries.

Some sections of the Jamaat party were of the view that matters with regard to the orientation of governance are best left to the incoming parliament to decide on but such opinions will be cold comfort for minority groups. If the parliamentary majority comes to consist of hard line Islamists, for instance, there is nothing to prevent the country from going in for theocratic governance. Consequently, minority group fears over their safety and protection cannot be prevented from spreading.

Therefore, we come back to the question of just and fair governance and whether Bangladesh’s future rulers could ensure these essential conditions of democratic rule. The latter, it is hoped, will be sufficiently perceptive to ascertain that a Bangladesh rife with religious and ethnic tensions, and therefore unstable, would not be in the interests of Bangladesh and those of the region’s countries.

Unfortunately, politicians region-wide fall for the lure of ethnic, religious and linguistic chauvinism. This happens even in the case of politicians who claim to be democratic in orientation. This fate even befell Bangladesh’s Awami League Party, which claims to be democratic and socialist in general outlook.

We have it on the authority of Taslima Nasrin in her ground-breaking novel, ‘Lajja’, that the Awami Party was not of any substantial help to Bangladesh’s Hindus, for example, when violence was unleashed on them by sections of the majority community. In fact some elements in the Awami Party were found to be siding with the Hindus’ murderous persecutors. Such are the temptations of hard line majoritarianism.

In Sri Lanka’s past numerous have been the occasions when even self-professed Leftists and their parties have conveniently fallen in line with Southern nationalist groups with self-interest in mind. The present NPP government in Sri Lanka has been waxing lyrical about fostering national reconciliation and harmony but it is yet to prove its worthiness on this score in practice. The NPP government remains untested material.

As a first step towards national reconciliation it is hoped that Sri Lanka’s present rulers would learn the Tamil language and address the people of the North and East of the country in Tamil and not Sinhala, which most Tamil-speaking people do not understand. We earnestly await official language reforms which afford to Tamil the dignity it deserves.

An acid test awaits Bangladesh as well on the nation-building front. Not only must all forms of chauvinism be shunned by the incoming rulers but a secular, truly democratic Bangladesh awaits being licked into shape. All identity barriers among people need to be abolished and it is this process that is referred to as nation-building.

On the foreign policy frontier, a task of foremost importance for Bangladesh is the need to build bridges of amity with India. If pragmatism is to rule the roost in foreign policy formulation, Bangladesh would place priority to the overcoming of this challenge. The repatriation to Bangladesh of ex-Prime Minister Hasina could emerge as a steep hurdle to bilateral accord but sagacious diplomacy must be used by Bangladesh to get over the problem.

A reply to N.A. de S. Amaratunga

A response has been penned by N.A. de S. Amaratunga (please see p5 of ‘The Island’ of February 6th) to a previous column by me on ‘ India shaping-up as a Swing State’, published in this newspaper on January 29th , but I remain firmly convinced that India remains a foremost democracy and a Swing State in the making.

If the countries of South Asia are to effectively manage ‘murderous terrorism’, particularly of the separatist kind, then they would do well to adopt to the best of their ability a system of government that provides for power decentralization from the centre to the provinces or periphery, as the case may be. This system has stood India in good stead and ought to prove effective in all other states that have fears of disintegration.

Moreover, power decentralization ensures that all communities within a country enjoy some self-governing rights within an overall unitary governance framework. Such power-sharing is a hallmark of democratic governance.

Features

Celebrating Valentine’s Day …

Valentine’s Day is all about celebrating love, romance, and affection, and this is how some of our well-known personalities plan to celebrate Valentine’s Day – 14th February:

Valentine’s Day is all about celebrating love, romance, and affection, and this is how some of our well-known personalities plan to celebrate Valentine’s Day – 14th February:

Merlina Fernando (Singer)

Yes, it’s a special day for lovers all over the world and it’s even more special to me because 14th February is the birthday of my husband Suresh, who’s the lead guitarist of my band Mission.

We have planned to celebrate Valentine’s Day and his Birthday together and it will be a wonderful night as always.

We will be having our fans and close friends, on that night, with their loved ones at Highso – City Max hotel Dubai, from 9.00 pm onwards.

Lorensz Francke (Elvis Tribute Artiste)

On Valentine’s Day I will be performing a live concert at a Wealthy Senior Home for Men and Women, and their families will be attending, as well.

I will be performing live with romantic, iconic love songs and my song list would include ‘Can’t Help falling in Love’, ‘Love Me Tender’, ‘Burning Love’, ‘Are You Lonesome Tonight’, ‘The Wonder of You’ and ‘’It’s Now or Never’ to name a few.

To make Valentine’s Day extra special I will give the Home folks red satin scarfs.

Emma Shanaya (Singer)

I plan on spending the day of love with my girls, especially my best friend. I don’t have a romantic Valentine this year but I am thrilled to spend it with the girl that loves me through and through. I’ll be in Colombo and look forward to go to a cute cafe and spend some quality time with my childhood best friend Zulha.

JAYASRI

Emma-and-Maneeka

This Valentine’s Day the band JAYASRI we will be really busy; in the morning we will be landing in Sri Lanka, after our Oman Tour; then in the afternoon we are invited as Chief Guests at our Maris Stella College Sports Meet, Negombo, and late night we will be with LineOne band live in Karandeniya Open Air Down South. Everywhere we will be sharing LOVE with the mass crowds.

Kay Jay (Singer)

I will stay at home and cook a lovely meal for lunch, watch some movies, together with Sanjaya, and, maybe we go out for dinner and have a lovely time. Come to think of it, every day is Valentine’s Day for me with Sanjaya Alles.

Maneka Liyanage (Beauty Tips)

On this special day, I celebrate love by spending meaningful time with the people I cherish. I prepare food with love and share meals together, because food made with love brings hearts closer. I enjoy my leisure time with them — talking, laughing, sharing stories, understanding each other, and creating beautiful memories. My wish for this Valentine’s Day is a world without fighting — a world where we love one another like our own beloved, where we do not hurt others, even through a single word or action. Let us choose kindness, patience, and understanding in everything we do.

Janaka Palapathwala (Singer)

Janaka

Valentine’s Day should not be the only day we speak about love.

From the moment we are born into this world, we seek love, first through the very drop of our mother’s milk, then through the boundless care of our Mother and Father, and the embrace of family.

Love is everywhere. All living beings, even plants, respond in affection when they are loved.

As we grow, we learn to love, and to be loved. One day, that love inspires us to build a new family of our own.

Love has no beginning and no end. It flows through every stage of life, timeless, endless, and eternal.

Natasha Rathnayake (Singer)

We don’t have any special plans for Valentine’s Day. When you’ve been in love with the same person for over 25 years, you realise that love isn’t a performance reserved for one calendar date. My husband and I have never been big on public displays, or grand gestures, on 14th February. Our love is expressed quietly and consistently, in ordinary, uncelebrated moments.

With time, you learn that love isn’t about proving anything to the world or buying into a commercialised idea of romance—flowers that wilt, sweets that spike blood sugar, and gifts that impress briefly but add little real value. In today’s society, marketing often pushes the idea that love is proven by how much money you spend, and that buying things is treated as a sign of commitment.

Real love doesn’t need reminders or price tags. It lives in showing up every day, choosing each other on unromantic days, and nurturing the relationship intentionally and without an audience.

This isn’t a judgment on those who enjoy celebrating Valentine’s Day. It’s simply a personal choice.

Melloney Dassanayake (Miss Universe Sri Lanka 2024)

I truly believe it’s beautiful to have a day specially dedicated to love. But, for me, Valentine’s Day goes far beyond romantic love alone. It celebrates every form of love we hold close to our hearts: the love for family, friends, and that one special person who makes life brighter. While 14th February gives us a moment to pause and celebrate, I always remind myself that love should never be limited to just one day. Every single day should feel like Valentine’s Day – constant reminder to the people we love that they are never alone, that they are valued, and that they matter.

I truly believe it’s beautiful to have a day specially dedicated to love. But, for me, Valentine’s Day goes far beyond romantic love alone. It celebrates every form of love we hold close to our hearts: the love for family, friends, and that one special person who makes life brighter. While 14th February gives us a moment to pause and celebrate, I always remind myself that love should never be limited to just one day. Every single day should feel like Valentine’s Day – constant reminder to the people we love that they are never alone, that they are valued, and that they matter.

I’m incredibly blessed because, for me, every day feels like Valentine’s Day. My special person makes sure of that through the smallest gestures, the quiet moments, and the simple reminders that love lives in the details. He shows me that it’s the little things that count, and that love doesn’t need grand stages to feel extraordinary. This Valentine’s Day, perfection would be something intimate and meaningful: a cozy picnic in our home garden, surrounded by nature, laughter, and warmth, followed by an abstract drawing session where we let our creativity flow freely. To me, that’s what love is – simple, soulful, expressive, and deeply personal. When love is real, every ordinary moment becomes magical.

Noshin De Silva (Actress)

Valentine’s Day is one of my favourite holidays! I love the décor, the hearts everywhere, the pinks and reds, heart-shaped chocolates, and roses all around. But honestly, I believe every day can be Valentine’s Day.

It doesn’t have to be just about romantic love. It’s a chance to celebrate love in all its forms with friends, family, or even by taking a little time for yourself.

Whether you’re spending the day with someone special or enjoying your own company, it’s a reminder to appreciate meaningful connections, show kindness, and lead with love every day.

And yes, I’m fully on theme this year with heart nail art and heart mehendi design!

Wishing everyone a very happy Valentine’s Day, but, remember, love yourself first, and don’t forget to treat yourself.

Sending my love to all of you.

Features

Banana and Aloe Vera

To create a powerful, natural, and hydrating beauty mask that soothes inflammation, fights acne, and boosts skin radiance, mix a mashed banana with fresh aloe vera gel.

To create a powerful, natural, and hydrating beauty mask that soothes inflammation, fights acne, and boosts skin radiance, mix a mashed banana with fresh aloe vera gel.

This nutrient-rich blend acts as an antioxidant-packed anti-ageing treatment that also doubles as a nourishing, shiny hair mask.

* Face Masks for Glowing Skin:

Mix 01 ripe banana with 01 tablespoon of fresh aloe vera gel and apply this mixture to the face. Massage for a few minutes, leave for 15-20 minutes, and then rinse off for a glowing complexion.

* Acne and Soothing Mask:

Mix 01 tablespoon of fresh aloe vera gel with 1/2 a mashed banana and 01 teaspoon of honey. Apply this mixture to clean skin to calm inflammation, reduce redness, and hydrate dry, sensitive skin. Leave for 15-20 minutes, and rinse with warm water.

* Hair Treatment for Shine:

Mix 01 fresh ripe banana with 03 tablespoons of fresh aloe vera gel and 01 teaspoon of honey. Apply from scalp to ends, massage for 10-15 minutes and then let it dry for maximum absorption. Rinse thoroughly with cool water for soft, shiny, and frizz-free hair.

-

Features5 days ago

Features5 days agoMy experience in turning around the Merchant Bank of Sri Lanka (MBSL) – Episode 3

-

Business6 days ago

Business6 days agoZone24x7 enters 2026 with strong momentum, reinforcing its role as an enterprise AI and automation partner

-

Business5 days ago

Business5 days agoRemotely conducted Business Forum in Paris attracts reputed French companies

-

Business5 days ago

Business5 days agoFour runs, a thousand dreams: How a small-town school bowled its way into the record books

-

Business5 days ago

Business5 days agoComBank and Hayleys Mobility redefine sustainable mobility with flexible leasing solutions

-

Business2 days ago

Business2 days agoAutodoc 360 relocates to reinforce commitment to premium auto care

-

Business6 days ago

Business6 days agoHNB recognized among Top 10 Best Employers of 2025 at the EFC National Best Employer Awards

-

Midweek Review2 days ago

Midweek Review2 days agoA question of national pride