Features

Medical Humanities:an interdisciplinary approach to holistic health

The Department of Medical Humanities at the University of Colombo’s Medical Faculty is another groundbreaking initiative by the institution as the pioneer of the discipline here at home and in South Asia. In an interview with the Sunday Island, Clinical Psychologist and Head of the Department of Medical Humanities, Dr. Santushi Amarasuriya elucidates on how this discipline, which is gaining momentum the world over, explores human experiences of health and illness drawing from a spectrum of other social and aesthetic branches.

Following are the excerpts:

BY RANDIMA ATTYGALLE

Q: Could you please share the ‘story’ behind the establishment of the Department of Medical Humanities at the Colombo Medical Faculty?

A:The Department of Medical Humanities was established in 2016 in response to global trends which recognize the role of medical humanities in medical education. It helps medical practitioners to reorient themselves into a holistic and person-centered approach to health care. There was also a general recognition of the impact of burnout and resultant empathy-deficits among medical practitioners, with medical humanities seen as a mechanism through which doctors can understand, reflect upon and deal with such issues. It is in recognition of all this that our Department was established.

Medical humanities lies at the intersection of medicine and humanities. It draws from various disciplines; from literature and philosophy to ethics and arts. The scope of medical humanities is very broad and therefore we find varying definitions of it. How we define it here at the Colombo Medical Faculty, is as ‘humanities in the pursuit of improving the well being and achieving goals in medical education.’ Our goal is to use medical humanities to foster compassionate care, professionalism and ethical practice among medical and other health care professionals, whilst also being sensitive to the socio-cultural context in Sri Lanka.

If we look at the specific history of how the department came into being, one of the highlights was when a brand-new stream called the Behavioural Sciences Stream, first conceptualized by Prof. Nalaka Mendis, was established within the curriculum of our Faculty in 1995. This was a pioneering effort that recognized the transition of the medical model of illness, which focused primarily on biological factors, into what is known as the bio-psychosocial model of health and illness in the late 70s. This latter model takes a more holistic approach and recognizes that there are psychological and social elements that also determine the outcomes of an illness.

Then, during a revision of the Behavioural Sciences Stream curriculum in 2013, Prof. Panduka Karunanayake proposed the establishment of a Medical Humanities Unit. The ensuing discussions led to Prof. Godwin Constantine proposing the establishment of a department. Subsequently, Prof. Saroj Jayasinghe, who was the Chairperson of the Behavioural Sciences Stream at the time became the driving force in establishing the Department in 2016, becoming its founder Head.

I was the first permanent academic staff member to have been recruited to the Behavioural Sciences Stream in 2006 and after the establishment of the Department of Medical Humanities in 2016, I came on board as its first Senior Lecturer.

Q: Could you elaborate on the nature of the learning enabled for the medical student by the Department and how medical humanities help students to brave a demanding curriculum with empathy and kindness?

A: Our main teaching input is through the Humanities, Society and Professional Stream, previously known as the Behavioural Sciences Stream. We provide input into areas of personality development and psychology, communication skills, ethical practice, professionalism, and humaneness, utilizing different teaching methodologies.

If I were to address the topic of empathy that you highlighted, many of our activities try to cultivate this skill in students. However, I would say it is not easy to develop. Many studies have shown that when medical students reach the third year, which is when they start their clinical rotations and need empathy the most, there is actually a decline of it. This is referred to as the ‘devil in the third year’. Many reasons are attributed to this. For example, what was hypothetical is now actually real and students are suddenly overwhelmed with a higher level of responsibility because now they are taking care of real people. There is also a marked increase in workload and it could also be the lack of role models. All this might lead to a decline in empathy. But we must remember that empathy is a hard job, stepping into another person’s shoes and understanding their problems, such as what is making them distressed. To make it even more challenging, it would be multiple patients whose shoes they have to step into and that can be really exhausting.

As a human being, your natural defense mechanism would be to detach yourself and not be empathetic. Therefore, what we try to do is to recalibrate, talk about and reinforce the importance of it.

Q: Could you please explain how the wide range of disciplines coming under medical humanities is translated into actual practice by physicians?

A: One of the methodologies that we have adopted is to use narratives in medicine. Very early in the students’ career, we ask them to go and draw from patients their personal story, and NOT their clinical history. This helps to cultivate a holistic approach to medicine. As a clinician, when you take a clinical history, you are very cognizant that there is a lot more going on for the patient than merely their disease.

A simple exercise that some international institutions utilize is to take students on a gallery visit where they are asked to study portraits to sharpen their finer observational skills; they start learning to notice certain physical signs or certain subtle cues that may have escaped attention. Therefore, at the point of their interaction with patients, they become more attuned to reading many nonverbal cues. For example, take a well-known painting like the Mona Lisa. Closer observation reveals her pale complexion, swollen hands and puffiness around her eyes, which can be used to hypothesize possible ailments she may have suffered from.

Similarly, certain films can be used to create a stimulating dialogue about patient-experiences. They are able to trigger strong emotional reactions and then also provide a safe space to discuss difficult topics which may be inaccessible if only relying on personal experiences. Another tool that I personally find fascinating, that is adopted by some of our colleagues in the region, is the use of the ‘spectator’ concept within forum theatre, where the spectators have the opportunity to intervene and become the actors to change the outcomes of stories depicting difficult situations.

This highlights and empowers the students in their future roles as reflective change agents. Medical students can also be helped to actually step into the patient’s shoes and share the experience of the patient. For example, what is it like to be wheelchair-bound or lack the use of a limb so that they could relate to a patient’s situation better. There is a wide array of methodologies, and this is important given the diversity of student preferences.

Q Is it justifiable to say that this interdisciplinary approach has gained momentum today as the innate ‘humane humaneness’ coupled with professionalism which was found in the good old doctor of yesteryear is largely eroding today, replaced by a stereotypical fact-finder?

A: The importance of humaneness in medical care is well recognized now. The concept of person-centred or patient-centered care is known to a medical student and medical curricula all over the world are adopting these concepts now. If you ask a medical student what empathy is, they will regurgitate the definition and they also know it is important. I would argue that maybe in the good old days these definitions might have been rather alien, but the values these definitions entail may have been innate in most physicians.

That is not to say that there aren’t many students with such skills today. But previously, medical professionals might have had time to actually cultivate these abilities and skills; they might have been able to immerse themselves in the arts. Whereas now, the landscape is very different due to the sheer volume of information to digest, too many competing demands and so forth. Therefore, it becomes a matter of prioritization and many are driven to only focus on the more tangible and measurable elements.

A second reason is the structure of our education. If you take the A-Levels, it’s a rat race to get into the medical faculty and how you get there is by knowing all the information to answer the questions. Along the way you may not have had time for extensive reflection or contemplation. The student who comes to us is trained in that way. So, when they take a clinical history, they may be more driven to simply gather data and make a diagnosis. They forget the holistic nature of the interaction along the way.

Q: Do you think the relevance of medical humanities is unprecedented today given the shift in socio-economic dynamics in society?

A: As a country we have faced several calamities and the most recent one is the economic crisis. Along with it there are several other problems that our people have to face: a significant number is impoverished and there has been a lack of medical supplies and an exodus in the medical profession itself. So, if you think about the professionals working today, they are overloaded with work, and this can lead to a sense of helplessness and frustration.

If you place it within Maslow’s hierarchy of needs, they may be struggling to meet basic needs. So higher-level needs like compassion and empathy start to look more like “nice-to-haves” than necessities, given that they are trying to deliver in a context that is resource-poor. It really is a balancing act. Therefore, it is often all too easy to satisfy ourselves with aggregate numbers. For instance, we say there are low rates of infant mortality and few maternal deaths. But what we might overlook in those aggregates is the experience that the patient has had in this whole process. What we do in our curriculum is re calibrate and remind them of what is finally needed.

Q: Today many patients lament that doctors are ‘poor communicators’, that their body language often doesn’t foster a sense of comfort and security in a patient. How does medical humanities envisage to address this so that doctors can be better communicators?

A: As a Faculty, we all endorse the importance of communication skills, and the input is given at different stages not only through our Humanities, Society and Professionalism Stream (HSPS) but through the other teaching arms as well. Interestingly, many students know the science behind communication practices, such as starting with an open-ended question, but they may not know HOW to do it. There’s a lot of art in asking a question. Although they may not have the innate gift of being effective communicators, with the right training, they can be developed into very successful ones.

In some of our activities we use different works of art, such as movies, paintings, poems, stories and so forth. In the recent past, we have used the painting titled ‘The Doctor’ by Luke Fildes. In the painting, a doctor is hovering over an ill child and we ask the students to interpret what’s going on. A lot is being communicated in this visual such as the stance of the doctor, the nonverbal behaviour, and in the background are the child’s parents who have entrusted the child to the doctor’s care. So just asking the students to analyze it and talk about it helps them to reflect. We use many other such methodologies to foster good communication in future doctors.

Another tool we often use is role-play. We recently launched a Communication Skills Master Class under the guidance of Prof. Dinithi Fernando, the current Chairperson of the HSPS, to give more muscle to the enhancement of communication skills.

Q: What are Sri Lanka’s strengths as a multi-cultural and a hospitable nation that medical humanities could draw from?

A: We are a collective community and helping another human being in distress, is very much a part of our culture. It comes very naturally and that translates into the process of healing a patient in distress. Kindness and compassion are key messages that are collectively shared by all our religions practiced here at home. If you consider kindness, I think of it at two levels: people whose core is kind and those who superficially reflect kind behaviour such as talking in a nice way and similar social graces. But this second category may not be kind deep down. Now if you think about our cultural orientation, it is that first one which is emphasized- kindness at the core. What we are trying to harness is a natural or deeply culturally-endorsed tendency.

Another example is the cultural sensitivity that we may already possess. We have students coming from different contexts and different experiences. They already recognize the existence of ‘health pluralism’ and that the patient’s conceptualizations of illness and treatment encompass a wide range of practices and beliefs that are not directly relevant to western medical practice. Therefore, it is just a matter of reminding them of these to help them to be more empathetic about patient experiences.

Q: What are the collaborations the Department has forged with professionals outside the medical stream to cultivate a sense of appreciation in aesthetics in future doctors?

A: One good example is our Humanitas programme. This is the brainchild of Prof. Panduka Karunanayake. The Latin term humanitas translates into human nature, civilization and kindness and relates to what it is that makes us human. In this programme we address various human issues – be it a current crisis or a problem like a heart break.

Prof. Karunanayake’s objective in launching this programme was to trigger an emotional reaction and let the other cognitive processes occur on their own. The Humanitas programme is solely directed by Dr. Santhushya Fernando who is a Senior Lecturer in our Department, where she gets in different artists from musicians to poets to talk about such issues and reflect and share their vulnerabilities, giving flavour to the programme. The programme has received very good reviews and all credit for this must go to Dr. Fernando who has spearheaded this programme with passion and enthusiasm.

Similarly, we have been fortunate to receive generous support from the academics of the University of Visual and Performing Arts who have not only made wonderful contributions to the Humanitas programme but to many other activities of the Department.

Q: What inspiration does the Colombo Faculty offer other medical faculties in the country in terms of recognizing medical humanities and what are the future plans of your Department to give a further thrust to medical humanities?

A: Even in terms of the Behavioural Sciences Stream, we were pioneers and all other faculties have now adopted it under different names. It is heartening to note that many of the medical faculties here have taken a cue from our experience. Although they may not have a dedicated department to the discipline, many have incorporated these ideas into their curriculum.

In terms of expansion, we have many plans which are aligned with the goals of our Department such as using the humanities to facilitate health education and training, initiating research by drawing from best practices which could be replicated here at home and also to enrich our curriculum. We plan to explore on how to enable more patient-friendly environments so that our future doctors can actually translate the concepts espoused by the humanities, into actual practice and also explore the role of the discipline in developing therapies or interventions to promote health.

The department has now been allocated a larger space within the Faculty to grow and expand but lacks facilities to make it an occupiable space. We are seeking donations from philanthropists and wellwishers to make this project a reality.

Features

Defining Oxygen Economy for sustaining life on Earth and growing intergenerational wealth

by Dr. Ranil Senanayake

The Oxygen that is present in the air that we breathe is the birth right of every organism that lives on this planet. It is free for everyone. However, the action of some to take out more than their share, without replacement, has created a condition, where the Global Commons of air is being rapidly degraded,

The most critical component of air is Oxygen. It surrounds us, filling our lungs with every breath we take. It is the invisible gift of nature that we take for granted. But this essential resource—the very foundation of life— is being constricted, because the volume of trees, plants, and photosynthetic organisms that produce oxygen is being lost across the planet. Further, there is no initiative for this generation capacity to be increased as a matter of urgency. exploited at present? Why couldn’t increasing the generation capacity of Oxygen have economic value? Could those who benefit most from using the resources of the Global Commons be required to contribute to its maintenance? This is the idea behind the Oxygen Economy, a bold and transformative concept that seeks to address environmental and social challenges in a way that is fair, sustainable, and forward-thinking beyond GDP value which measures the success of our societies today.

What Is the Oxygen Economy?

The Oxygen Economy is a financial framework, that recognises the value of the global stocks of Oxygen within the commons and records the deposition and consumption through economic activity.

The Oxygen Economy is a principled framework that recognises the stocks, transactions and deposits of Oxygen into the Global commons and assigns value to stocks from privately contracted production units, it stems from a growing recognition that Oxygen is a declining resource with an easy replenishment response.

Oxygen, considered a “free” resource. It is not. Much like oil and coal it is a ‘fossil’ resource that has been a part of the atmosphere for millions of years. It has been slowly declining, but is ‘topped up’ by a service provided by the earth’s ecosystems —particularly trees, plants, and other photosynthetic organisms. These organisms create molecular Oxygen through the process of photosynthesis, supporting life on earth and maintaining the balance of our atmosphere.

At its core, the Oxygen Economy aims to ensure that those who produce contracted and monitored oxygen, be it towns, farmlands, rural or forested lands, are fairly compensated for their efforts. It also holds industries and private-sector entities that benefit from oxygen consumption accountable in maintaining the sustainability of this resource.

What is the urgency to address oxygen as a depleting resource?

Other than the obvious fact of falling global stocks, the need of an Oxygen Economy arises from the urgency of addressing two critical challenges facing humanity: environmental degradation and economic inequality. Placing value on Oxygen production could effectively provide an effective response to both. For decades, efforts to combat climate change have focused primarily on carbon

sequestration. While important, the focus on Carbon sequestration often overlooks other vital ecosystem services, including oxygen production that can contribute towards a growing wealth paradigm. Oxygen, like water and food, is essential for life. However, unlike other resources, it has largely been treated as infinite and freely available, which it is not. In reality, the supply of Oxygen to the atmosphere is decreasing due to deforestation, while the consumption of Oxygen by space exploration, industrial production, war and transport are increasing. Today Oxygen levels have dropped by approximately 2%, raising concerns about the long- term sustainability of this critical resource.

How the Oxygen Economy works

The Oxygen Economy operates on the principles of private property being valued using financial tools such as valuation guarantees, stakeholder contracts and Insurances to monetise contractually produced oxygen as a financial product. This involves three key components:

1. Valuation guarantee:

Assigning an economic value to the oxygen produced by contracted and registered units in identified geographical areas of production is based on the researched, monitored and validated measurements of oxygen generation by trees / plants or photosynthetic organisms such as Cyanobacteria.

2. Deposition guarantee:

Issuance of certificates of completion and deposit of Oxygen into the global Commons Stakeholder Contracts and Compensation: Establishing formal agreements between oxygen consumers (e. g., corporations / Space exploration companies) and contracted oxygen producers (e.g., farmers, Local communities)

3. Policy and regulation: Introducing replicable legal frameworks at a regional scale to enforce accountability and prevent the uncontrolled exploitation of global oxygen resources.

Lessons from Sri Lanka

One country that is already exploring the potential of the Oxygen Economy is in the bioregional area of Sri Lanka. Known for its rich biodiversity and commitment to environmental stewardship, Sri Lanka has implemented initiatives that align with the principles of the Oxygen Economy. In one notable project, women from farming communities established and nurtured trees using contracts that measured and validated payments for photosynthetic biomass on an annually recurring basis for a period of four years. The stakeholders earning substantive income from this project were sensitised to the emerging Oxygen Economy while contributing their obligations to global environmental resilience. Over three years, these participants generated thousands of litres of oxygen, demonstrating that the concept is not only viable but also impactful.

Scaling the Oxygen Economy globally:

While Sri Lanka’s efforts are a promising start, the true potential of the Oxygen Economy

lies in its ability to scale globally. Imagine a world where farmers are compensated for the establishment of trees, where rural and even urban greenery projects could receive funding to expand their impact for this paradigm of business. Such a system would not only help combat climate change but also address economic inequalities of the current GDP paradigm, by together contracting the Oxygen economic asset tool to those who sustain the planet’s life-support systems.

Addressing potential challenges

Like any transformative idea, the Oxygen Economy faces potential challenges. Critics may argue that assigning a monetary value to Oxygen risks commodifying a natural resource that should remain freely accessible. Others may question the feasibility of measuring, validating and regulating oxygen production on a global scale. These concerns can be addressed by emphasising the ethical principles behind the Oxygen Economy. The goal is not to charge people for breathing but to ensure that those who contribute to its sustainability profit from financial contracts for Oxygen production. Additionally, such transparent systems for measuring and validating oxygen production will be crucial for building trust and ensuring fairness towards the vision of accounting for intergenerational wealth beyond the GDP framework that exists.

A vision for the future

The Oxygen Economy represents a paradigm shift in how we think about our relationship with the planet. It challenges us to move beyond the notion of nature as an infinite resource and to recognise the boundaries of our Global Commons. The true value of planet Earth is as an ecosystem that sustains life for all biota. By aligning economic practices with environmental stewardship, the Oxygen Economy offers a path towards a more equitable and sustainable future. It supports the foundations of intergenerational wealth that will be reflected in our contributions to the cycling atmospheric gasses of our Global Commons.

Imagine a world where the air we breathe is not taken for granted but is cherished and protected. Where farmers, communities, and ecosystems are rewarded for their contributions to the planet’s well-being. Where industries operate with a framework of accountability to prioritise the health of our shared environment. This is the vision of the Oxygen Economy—a vision that is within our reach if we act together, with urgency and determination, to lay well informed, solid foundations.

Features

Two sides to a coin; each mourn threat; no threat, no budget blues

The coin Cassandra starts her Friday Cry with the recent film Rani. Parroting what her friends said on seeing the film, Cass in her Cry just prior to this wrote: “It has been reviewed as outstanding; raved over by many; and already grossed the highest amount in SL cinema history – Rs 100 million from date of release January 30 to February 14. This last: testimony to its popular appeal and acceptance as an outstanding cinema achievement.

The coin Cassandra starts her Friday Cry with the recent film Rani. Parroting what her friends said on seeing the film, Cass in her Cry just prior to this wrote: “It has been reviewed as outstanding; raved over by many; and already grossed the highest amount in SL cinema history – Rs 100 million from date of release January 30 to February 14. This last: testimony to its popular appeal and acceptance as an outstanding cinema achievement.

” Cass admitted she had not seen the film. She now realises her reluctance to jostle in the crowd in one of many cinemas retelling the murder of Richard de Zoysa and traumatic mourning of his mother, Manorani, was because there grew in her a distaste after watching short previews on YouTube of parts of the film. Most centered on is Swarna Mallawarachchi, starring as Manorani, downing alcohol and smoking cigarette after cigarette. Director Asoka Handagama was sensationlising the more dramatic incidents of the tragedy. That was to please the crowd.

We Sri Lankans, or many, have absolutely no tight upper lip. Most funerals of yesteryear and many rural ones still have writhing moaning and groaning and appeals to the dead to smile one more time, say a word, rise up. These loud gasped cries in between sobbing sent Cass wickedly into silent giggles. She thought: what if the dead obliged with even one request. Worst, if he rose up and sat in his coffin. The first to run away would be the callers! People love wallowing in sniffles of sorrow. Audiences much prefer fictionalised retelling of events to documentaries about them. Handagama does style his film as fictionalised history but he definitely is guilty of sensationalism. Cass’ gut feelings have been given words in a criticism on Face Book which was shared with Cass by a nephew.

The sent around message is titled: Misconceived, Misinterpreted, Miscast and a Big Mistake. That tells it all. However there follows an incisive critique of the film Rani by one of Richard’s friends who knew Manorani well and how she was after her son’s death. He signs himself, but Cass will not quote the name here since there is much truth, lies and even hidden agendas in what is posted on social media.

He writes: “Badly acted, badly directed and badly researched … A clear example of character assassination via a deliberate misuse of artistic license! … I want to state my opinion about two people that many of us loved, respected and knew intimately.” He then goes on to point out mistakes and exaggerations: Manorani was never even bordering on alcoholism and hardly ever smoked. And when she did, socially or to dim her sorrow, she did it elegantly. A Man Friday commented: they should have taught Swarna how to hold a cigarette and smoke it as it should be smoked. Hence my contention, every coin, even a box office success, has two sides to it, two diverse criticisms and in-betweens. Decision: Cass will not queue for a cinema ticket.

Each morn

Phoned a US living friend who was recovering from a harsh winter’s gift to her – severe flu. She said the flu was leaving her but depression and distraught-ness about hers and the US’s future were threatening to drown her in emotional turmoil much worse than the worst cough ‘n cold.

I knew the reason – Trump’s trumpets of new opinions, threats, enactments et al. She dreaded getting up each morning wondering what new calamity was to descend on the American people and by influence, spreading to the world. Her son has forbidden TV news watching and reading the newspapers which she says are so opposed to media treatment of the Prez.

I could very well sympathise with her. We in Sri Lanka suffered bouts of such threatened discomfort, nay calamitous warnings and sheer dread. My remembering mind went to Shakespeare in his tragic play Macbeth. Macduff’s description of Scotland under the reign of Macbeth to Malcolm, son and heir of murdered Duncan now sheltered in England, goes thus: “Each new morn/ New widows howl, new orphans cry/ new sorrows strike heaven on the face that it resounds.”

Cass does not know about you but dread lurked in her heart and mind when the JVP 1989 insurrection took place – for her teenage son. The LTTE and suicide bombs caused utter destruction of life, limb and infrastructure. Families who had travelled together now travelled to schools and workplaces separately since no bus or train was safe. Nor were the privately owned cars. Then came two tyrant Presidents with sudden deaths of prominent persons and media personnel like Richard and Lasantha and many others.

Blatant robbing of our money had us gasping helplessly. Riff raff rose in power and lorded, one such tying a man to a stake for not attending a meeting. Then rode to power on popular vote another brother in the newly created powerful dynasty. Word of mouth minus stroke of pen had orders given out to be promptly executed. White vans which plied the streets were reduced but worse happened.

One order and the rice fields had no grain, fruits dried on trees, forex earning luscious two leaves and a bud withered and could not be plucked. Bankruptcy resulted. But we had a ‘shipless’ harbour which had to be mortgaged for a song to the Chinese; a plane-less airport sounding death to elephants and peafowl; and a gaudy tower to gaze on or commit suicide from. A gathering of people on Galle Face Green righted things.

Then came into power a party that had two men and a woman in Parliament which yielded a true Sri Lankan with country first and last in mind, as President. Followed a sharp victory for the coalition of parties led by the hopefully reformed JVP so that three seats became almost two thirds of all seats in Parliament and a woman as Prime Minister. She had no connection to previous Heads unlike a former woman PM and Prez. The first woman PM rode to power weeping for her murdered husband; the younger very promising Prez because she was daughter of two Heads of Sri Lanka. But there was, even under their reign, mutterings and difficulties.

Truth be told, we sleep better at night and wake up with no dread in our innards. We rise to shine (if possible, in the heat of Feb) knowing people are working and corruption is not wrought by those in power. Thank goodness and our sensible voters for this peace we savour.

2025 Budget

Cass’ title has the phrase ‘no budget blues’. Looks like it is generally correct. Of course, the Opposition is criticising Finance Minister AKD’s presented budget. Cass is no economist, not by a long chalk, but she was glad to see that expenditure on health and education were substantial. We had a time when the armed forces were allocated more than education and health combined. Much has been looked into: including pregnant women and the Jaffna library among a host of mentioned amenities. We have no need to pessimistically await a Gazette Extraordinary stating negative segments of the future year’s financial plan. Thanks be!

Gaza and Ukraine are worse in position and the world is awry. But Sri Lanka is in a phase where Kuveni’s curse is stilled and people are considering themselves Sri Lankans, uniting to re-make Sri Lanka Clean as it was before selfish corrupt politicians took over.

Features

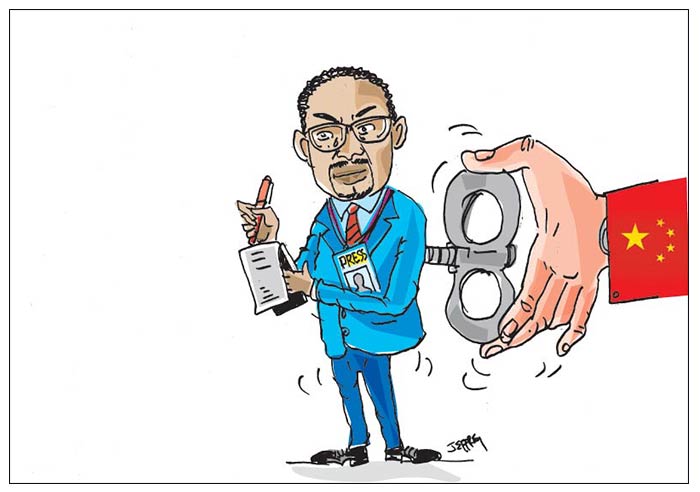

As Africa toes Chinese line …

Mitchell Gallagher

Every year, China’s minister of foreign affairs embarks on what has now become a customary odyssey across Africa. The tradition began in the late 1980s and sees Beijing’s top diplomat visit several African nations to reaffirm ties. The most recent visit, by Foreign Minister Wang Yi, took place in mid-January 2025 and included stops in Namibia, the Republic of the Congo, Chad and Nigeria.

For over two decades, China’s burgeoning influence in Africa was symbolised by grand displays of infrastructural might. From Nairobi’s gleaming towers to expansive ports dotting the continent’s shorelines, China’s investments on the continent have surged, reaching over $700 billion by 2023 under the Belt and Road Initiative, China’s massive global infrastructure development strategy.

But in recent years, Beijing has sought to expand beyond roads and skyscrapers and has made a play for the hearts and minds of African people. With a deft mix of persuasion, power and money, Beijing has turned to African media as a potential conduit for its geopolitical ambitions. Partnering with local outlets and journalist-training initiatives, China has expanded China’s media footprint in Africa. Its purpose? To change perceptions and anchor the idea of Beijing as a provider of resources and assistance and a model for development and governance. The ploy appears to be paying dividends, with evidence of sections of the media giving favourable coverage to China.

But as someone researching the reach of China’s influence overseas, I am beginning to see a nascent backlash against pro-Beijing reporting in countries across the continent. China’s approach to Africa rests mainly on its use of “soft power,” manifested through things like the media and cultural programmes. Beijing presents this as “win-win cooperation”—a quintessential Chinese diplomatic phrase mixing collaboration with cultural diplomacy. Key to China’s media approach in Africa are two institutions: The China Global Television Network (CGTN) Africa and Xinhua News Agency.

CGTN Africa, which was set up in 2012, offers a Chinese perspective on African news. The network produces content in multiple languages, including English, French and Swahili, and its coverage routinely portrays Beijing as a constructive partner, reporting on infrastructure projects, trade agreements and cultural initiatives. Moreover, Xinhua News Agency, China’s state news agency, now boasts 37 bureaus on the continent. By contrast, Western media presence in Africa remains comparatively limited.

The BBC, long embedded due to the United Kingdom’s colonial legacy, still maintains a large footprint among foreign outlets, but its influence is largely historical rather than expanding. And as Western media influence in Africa has plateaued, China’s state-backed media has grown exponentially. This expansion is especially evident in the digital domain. On Facebook, for example, CGTN Africa commands a staggering 4.5 million followers, vastly outpacing CNN Africa, which has 1.2 million—a stark indicator of China’s growing soft power reach. China’s zero-tariff trade policy with 33 African countries showcases how it uses economic policies to mould perceptions.

And state-backed media outlets like CGTN Africa and Xinhua are central to highlighting such projects and pushing an image of China as a benevolent partner. Stories of an “all-weather” or steadfast China-Africa partnership are broadcast widely and the coverage frequently depicts the grand nature of Chinese infrastructure projects. Amid this glowing coverage, the labour disputes, environmental devastation or debt traps associated with some Chinese-built infrastructure are less likely to make headlines. Questions of media veracity notwithstanding, China’s strategy is bearing fruit.

A Gallup poll from April 2024 showed China’s approval ratings climbing in Africa as US ratings dipped. Afrobarometer, a pan-African research organisation, further reports that public opinion of China in many African countries is positively glowing, an apparent validation of China’s discourse engineering. Further, studies have shown that pro-Beijing media influences perceptions. A 2023 survey of Zimbabweans found that those who were exposed to Chinese media were more likely to have a positive view of Beijing’s economic activities in the country. The effectiveness of China’s media strategy becomes especially apparent in the integration of local media.

Through content-sharing agreements, African outlets have disseminated Beijing’s editorial line and stories from Chinese state media, often without the due diligence of journalistic scepticism. Meanwhile, StarTimes, a Chinese media company, delivers a steady stream of curated depictions of translated Chinese movies, TV shows and documentaries across 30 countries in Africa. But China is not merely pushing its viewpoint through African channels. It’s also taking a lead role in training African journalists, thousands of whom have been lured by all-expenses-paid trips to China under the guise of “professional development.” On such junkets, they receive training that critics say obscures the distinction between skill-building and propaganda, presenting them with perspectives conforming to Beijing’s line.

Ethiopia exemplifies how China’s infrastructure investments and media influence have fostered a largely favourable perception of Beijing. State media outlets, often staffed by journalists trained in Chinese-run programmes, consistently frame China’s role as one of selfless partnership. Coverage of projects like the Addis AbabaDjibouti railway line highlights the benefits, while omitting reports on the substandard labour conditions tied to such projects—an approach reflective of Ethiopia’s media landscape, where state-run outlets prioritise economic development narratives and rely heavily on Xinhua as a primary news source. In Angola, Chinese oil companies extract considerable resources and channel billions into infrastructure projects.

The local media, again regularly staffed by journalists who have accepted invitations to visit China, often portray Sino-Angolan relations in glowing terms. Allegations of corruption, the displacement of local communities and environmental degradation are relegated to side notes in the name of common development. Despite all of the Chinese influence, media perspectives in Africa are far from uniformly pro-Beijing. In Kenya, voices of dissent are beginning to rise and media professionals immune to Beijing’s allure are probing the true costs of Chinese financial undertakings. In South Africa, media watchdogs are sounding alarms, pointing to a gradual attrition of press freedoms that come packaged with promises of growth and prosperity.

In Ghana, anxiety about Chinese media influence permeates more than the journalism sector, as officials have raised concerns about the implications of Chinese media cooperation agreements. Wariness in Ghana became especially apparent when local journalists started reporting that Chinese-produced content was being prioritised over domestic stories in state media.

Beneath the surface of China’s well publicised projects and media offerings, and the African countries or organisations that embrace Beijing’s line, a significant countervailing force exists that challenges uncritical representations and pursues rigorous journalism. Yet as CGTN Africa and Xinhua become entrenched in African media ecosystems, a pertinent question comes to the forefront: Will Africa’s journalists and press be able to uphold their impartiality and retain intellectual independence? As China continues to make strategic inroads in Africa, it’s a fair question.

(The writer is a PhD candidate of political science at Wayne State University, US. This article was published on www.theconversation.com)

-

Sports7 days ago

Sports7 days agoRemarkable turnaround for Sri Lanka’s ODI team

-

Features7 days ago

Features7 days agoScammed and Stranded: The Dark Side of Sri Lanka’s Migration Industry

-

Business7 days ago

Business7 days agoUN Global Compact Network Sri Lanka: Empowering Businesses to Lead Sustainability in 2025 & Beyond

-

Features6 days ago

Features6 days agoDon’t betray baiyas who voted you into power for lack of better alternative: a helpful warning to NPP – II

-

News4 days ago

News4 days agoCommercial High Court orders AASSL to pay Rs 176 mn for unilateral termination of contract

-

Sports3 days ago

Sports3 days agoSri Lanka face Australia in Masters World Cup semi-final today

-

Features6 days ago

Features6 days agoTwo films and comments

-

News7 days ago

News7 days agoInnovation Island Summit 2025, Colombo, Sri Lanka