Features

Marxism and nationalism: A never-ending debate (Part II)

Immediately after independence, the Sri Lankan Left faced an ideological dilemma for which it had not really been prepared. The government, headed by a comprador bourgeoisie, perhaps the most conservative and right-wing in Asia at the time, stepped in to deprive the estate Tamils of their citizenship. This slowly deprived the Left of its base in the plantations across the Uva and the South, right into the country’s south-western quadrant, limiting it to the cities, the working class. Elsewhere, in peasant strongholds, it made some strides. But the government’s careful, calculated cultivation of nationalist sentiment pre-empted the Left from mobilising them for a radical, truly emancipatory political project.

The government’s actions impacted these groups profoundly, adversely. The conventional reading of what happened next is this: lacking popular support among estate Tamils and the Sinhala middle-classes, the Left eventually pegged itself to the latter, compromising on its earlier, laudably progressive stance on languages and paving the way for a rapprochement with the SLFP. The latter, in the conventional reading, is often dismissed as a chauvinist and majoritarian party, in effect the political base of the Sinhala nationalist right. Anyone who chose the path of cohabitation with them, so the interpretation goes, shared or at least were complicit in the ideology of the nationalist right. Ergo, the Old Left is faulted if not chastised for bedding with the beast, with the harbinger of Sinhala chauvinism.

There is some truth to these allegations, and not all of them can be denied. But the dilemma the Left faced at the time could not have been more acute or complex. On the one hand, it lost the one community on whose behalf it had organised strikes and campaigns against the British and the UNP government. Such actions proved more than anything than the Left’s project did not just transcend ethnic distinctions, but also centred firmly on class issues. On the other hand, the UNP government proved itself capable, for a while at least, of rousing traditionalist elements, Sinhala and to a lesser extent Tamil, against the Left, on the basis of the latter’s supposed hostility to the past and to history.

Here the comprador bourgeoisie found a ready ally in conservative sections of the clergy. By that I mean not just the Christian clergy, including the Catholic and the Protestant. Their opposition to the Left was evident enough: they requested people not to vote for Marxist candidates, given Marxism’s “hostility” to religious values. The Buddhist clergy also sided with this view, and opposed or criticised monks who took to political activism. The latter, at least until after 1956, almost invariably swayed to the Left.

The point I am trying to get to here is simple. By 1956, the Left’s prospects had declined so badly that individual parties, including the LSSP, were already conceding the difficulty of forming a Left government. The 1956 election proved to be epochal here for two reasons. Firstly, it showed that the UNP’s hold over traditionalist elements was not absolute: these elements, disgruntled by the UNP’s policies, could defect to other parties, particularly those promising an alternative to the status quo which was less radical than the Marxist Left. In response the Left had to think of and come up with creative strategies, with which it could defeat the government while distancing itself from the Opposition. Eventually it settled on a policy of oppositional unity: thus, in some electorates it contested against other Opposition candidates, while in others it withdrew in favour of those candidates.

Secondly, the election showed how otherwise progressive ideals, once marginalised, could be reconfigured in pursuit of less than progressive ends. That is not to deny the immense vitality and popularity of the calls for Sinhala Only. Such calls underlay genuine grievances against the political establishment. Yet, instead of incorporating these grievances into an all-encompassing emancipatory project, the Sinhala middle-classes contented themselves on gaining the upper hand for themselves and for their identity. The tragedy here, for which we are still paying the price, is that such campaigns undermined the spirit with which the Left had earlier called for instituting the vernacular at official levels. The latter call was, in every respect, progressive, and it deserved being pursued till the very end. But the hysteria which usually accompanies elections in Sri Lanka eventually drowned it.

What I am critiquing here, essentially, are the political ideals of Sinhala nationalism. This, however, is a contradiction in terms: to have political ideals you must be part of a political project, and contemporary Sinhala nationalism, despite its rhetoric, has never had a properly coordinated political project against imperialism and neoliberalism. In that sense, I suppose, Sinhala nationalism is not hegemonic in the same way Hindutva is hegemonic in India, even if it shares much with the ideology of the RSS. The main problem with or limitation in Sinhala nationalism is that in its pursuit of national liberation, it defines the nation as the preserve of one collective, and overlooks or ignores the heterogenous character of not only the nation, but also that collective.

The truth is that Sinhala is not monolithic, and nor is Tamil. All claims to the contrary, no matter how enticing they may be, are facile and false.

Throughout the colonial period, the Left proved itself capable of tapping into the immense anti-imperialist potential of nationalist groups, while distancing itself from the comprador right’s alliances with such groups. The dynamics changed after independence, and by 1956 the Left had no choice but to question its former positions and, if possible, revise them. It did this with the hope – plausible as it appeared to be at the time – that the SLFP, and the Bandaranaikes, could be relied on to provide a ballast for a socialist advance in the country. But the Bandaranaikes were, for all intents and purposes, Bonapartists, who could sway to the Left or the Right depending on the situation. S. W. R. D. Bandaranaike did not live long enough to tilt completely to the right: it remains to be seen what he would have done had he survived his assassination. Yet, as his support for Philip Gunawardena’s Paddy Lands Bill showed, he was willing to support the Left in whatever way he could.

But Sinhala nationalism is deeply and utterly chameleonic: it is capable of turning against its allies. In 1975, spurred on by fears that the Left would unionise workers in plantations, the Sirimavo Bandaranaike government moved to expel the LSSP and the Communist Party from its ranks. The Left’s efforts at land reform, important as they were, fell short of what they had originally aimed at, largely because the SLFP’s right-wing sabotaged them. The Left, in all this, had to both adjust to and fight against such forces, and in doing so it paid a heavy price: not just expulsion from international Left collectives, but also rejection by the very milieus it had staked so much for. The great lesson of 1977 in that sense was that Sinhala nationalism, regardless of anti-imperialist potential, will never be a substitute for anti-imperialist politics so long as its purveyors fail to look beyond its cultural dimensions. The nationalist allegation against the Left today – that it is soft on minority issues, that it is not nationalist enough – is but a continuation of these conjunctions and contradictions.

Given all this, how should the Left reorganise itself? I recommend two strategies. First, it should try to weed away what Dayan Jayatilleka, at the Philip Gunawardena Oration in 2015, described as the rootless cosmopolitanism of many of our Left ideologues. There is nothing objectionable in being cosmopolitan: many of the original stalwarts of the Sri Lankan Left, after all, had been part of the aptly named “Cosmopolitan Crew.” But there is a difference, a distinction, between the cosmopolitanism espoused by these figures and the rejection, not of nationalism but of nationhood itself, by Left ideologues today. To quote Jayatilleka’s essay in Gramsci Today, “The Great Gramsci: Imagining an Alt-Left Project”,

“Our left contemporaries learned from much of what [Gramsci] wrote on hegemony and culture but missed one of his most important themes, that of the nation, nation building and state building. He understood that the left had abandoned those tasks and argued that picking up where Machiavelli left off was a task of the left, by which he meant wrestling with the tasks of nation and state building. Indisputably an internationalist, he notably criticized ‘cosmopolitanism’ as a doctrine that hampered the task of nation building.”

Simply put, national liberation is as much about liberation as it is about nationhood. The one cannot be weaned, still less cut off, from the other. Any group that attempts this does so at the risk of marginalising itself and pushing itself down an abyss.

Second, the Left should embark on embracing the ideals of nationhood without affirming, or associating with, the tenets and principles of the nationalist right. What constitutes the nationalist right is obviously a matter for conjecture, if not debate. The finer details need not concern us here. What is important is that the Left build bridges with communities which have been targeted by the nationalist right, and then attempt to convert them. This is not as difficult as it may seem. The strategy is to get these communities to realise that any national liberation project must focus on the nation, and the fundamental cleavage in any nation is not between ethno-religious groups, but between the masses and the elite. To quote a Sri Lankan poet, “the only minority is the bourgeoisie.” That should be the refrain of the Left as well, especially in its engagements with the Sinhala middle-classes.

It remains to be seen whether the Left can or will achieve a rapprochement with these groups. The Left tried once, and for a while it succeeded. Yet for reasons outlined above, it failed to transform that into the basis for a socialist advance in Sri Lanka. To castigate it for such failures would be to cry over spilt milk. But they certainly represent failures of the sort the Left should avoid today. To put it simply here, then, if the Left is to build a front against the economic right, it should be wary of allying itself with the nationalist right, but it should also recognise the anti-imperialist potential of nationalist movements without viewing and dismissing all as right-wing and reactionary. The latter, for me, is as bad an error as the Left’s act of capitulating to such forces. It does no harm at all to account for the specificity of these movements, or to recognise their distinctiveness. That hardly constitutes a regressive act for the Left; it in fact constitutes the only sensible alternative the Left has.

NB: This essay has benefited extensively from conversations with Dr Dayan Jayatilleka, Vinod Moonesinghe, and Shiran Illanperuma, as well as Pasindu Nimsara Thennakoon, who remains fascinated by the possibilities of the Sri Lankan Left.

The writer is an international relations analyst, researcher, and columnist who can be reached at udakdev1@gmail.com.

Features

‘Building Blocks’ of early childhood education: Some reflections

In infancy and childhood is laid the groundwork for an integrated personality in the making, in preparation for adaptation to the outside world. The malleability of the nervous system [neuroplasticity] due to its extensive growth during early childhood, considered to be the critical period for learning, offers the potential to bring about lifelong benefits in terms of social, emotional and intellectual development.

My goal in this brief article is to reflect on the essential elements [‘building blocks’] of education in early childhood which help to lay the foundation for positive outcomes in later life. It is intended to encourage conversation amongst the general readership of this important topic, especially the parents of young children, as learning begins at home.

Critical Period for learning

Early childhood usually covers the age range from infancy to about eight years of age, during which period most of the brain growth takes place. The prefrontal cortex of the brain responsible for higher cognitive functions [e. g. planning, decision making etc.] continues to mature into the mid-twenties. That isn’t to say that learning processes could not continue throughout life.

Current Community Attitudes towards Education

Let us first examine the current public attitudes towards education in general. Proficiency in reading, writing, math and science are regarded as the core academic literacies on which all other learning rests, and on which future success in life depends. The Arts and Humanities, a group of disciplines that study aspects of human society and culture, are placed lower in the hierarchy in the academic curriculum and are often considered supplementary. Their value in enhancing human ideals is often ignored. In a technologically advancing world we live in, the contribution of the study of the arts and humanities towards boosting the economy is brought into question.

The above attitude has created a highly competitive, exam driven, and hence stressful, academic environment for our children in their formative years. There are excessive demands placed upon them to achieve academically, exacerbated by parental pressure – overt or covert. Attendance at paid ‘tuition classes’, after hours, to supplement learning at school is considered essential to gain higher grades at exams, in order to be competitive in entering tertiary institutions and in enhancing career prospects. The love of learning is lost.

Many children find no time for reflection, or to read outside the curriculum to broaden their understanding about life. There is a perception in the community of a decline in literacy and sensibility in the young and their tendency to lean towards much less civilising forms of entertainment and communication, which is at the root of most of our social ills, compounded by the economic ills that currently plague us. Alarmingly, a recent survey by the College of Community Physicians of Sri Lanka has revealed that over 200 adolescents have committed suicide in 2024, which they, reportedly, attribute to their indulgence in social media. But at the heart of it is the breakdown of social order resulting in a lack of ‘meaning’ in life, as once postulated by the renowned French Sociologist, Emile Durkheim.

Family Milieu

The developing child requires the provision of certain environmental conditions, based on common principles, to complement the innate biological drive which we call instinct. Of vital importance is the family milieu, its stability and its ability to meet the child’s emotional needs. From an emotional point of view, the child needs to feel safe, and experience the contentment in the parent’s inter-relationship, in order to set the ground for learning. In addition, it helps for the parents to model the love of learning and of knowledge through communication in words and in actions.

In an ideal world, a child’s parents and teachers ought to be equally committed towards helping the child develop a love of learning. In some instances a teacher must shoulder most of the work – for instance, when parents are busy making a living or have had a limited education themselves.

Enrichment Strategies

Let us reflect on some of the enrichment strategies in early childhood education which would bring about a balance in the curriculum.

The Arts

“Engagement of children in the arts has the power to console, transform, welcome, and heal. It is what the world needs now” [Yo Yo Ma, Cellist]

The arts are commonly used as enrichment strategies in Early Childhood Education. They include music, dance, drama, and Visual and literary arts. The strengths developed through the arts during the early formative years have the potential to enhance other spheres of learning, and performance in later life. By eliciting emotions in the listener, the arts, as both Aristotle and Freud asserted, has the capacity to be therapeutic by being cathartic.

Music

Neuroscientists have shown that, due to the plasticity of the brain in young children, music training tended to enhance the auditory [hearing] pathways in the brain, and hence, the development of phonological awareness [responsiveness to contrasting sounds]. Phonological awareness is considered to be an important precursor to reading skill and the ability to rhyme. In addition, ‘Music is the language of emotions’, encouraging children to gain awareness of their own emotions in addition to making aesthetic judgements.

Drama

Research studies show that enacting stories in the classroom in comparison to dramatic performances on stage by children have several beneficial effects such as better understanding of the stories enacted and the appreciation of new stories. In addition, such classroom performances of stories enriched oral language development and reading skills, including an eagerness to read, and surprisingly, even writing skills.

Visual Arts

Engagement of children in visual art involves much more than learning the techniques of drawing and painting. Long periods of engagement in the craft provides a framework for enhancing thinking skills – to be more focussed and persistent in one’s work; to enhance the power of imagination; to generate a personal viewpoint or express a feeling state; and to encourage the child to reflect on and to make a critical judgement of their own work. Similarly, by entering into a conversation with the children after encouraging them to look closely at a piece of art, tended to heighten their observation skills. There is evidence that these habits of mind acquired from the engagement of children in visual arts could be ‘transferred’ to other areas of learning, and stand in good stead in employment in later life.

Reading

According to the British neuropsychologist, Andrew Ellis, the brain was never meant to read, in terms of human evolution: “There are no genes or biological structures specific to reading.” Reading had to be learned, requiring the integration and synchronisation of several systems of the brain acquiring a new neuronal circuitry for the purpose – perceptual, cognitive, phonemic, linguistic, emotional and motor. Reading, as it develops, aided by an environment that lures the child to read would lead to further enhancement of the cognitive capacity of the brain – an important dynamic in childhood education.

The more young children, are read to, and are engaged in conversation that flows on from stories read [‘conversational reading’], the more they begin to love books, increase their vocabulary and their knowledge of grammar, and appreciate the sounds that words generate – evidently, best predictors of later reading interest and critical thinking. Conversational reading is a technique where the parent or educator engages with the child in a conversation while reading a book, asking open-ended questions to encourage active participation and deeper comprehension, eg. entering into a dialogue about the story while reading it together.

In addition, reading enhances the child’s self-worth and personal identity [emotional experience of reading].

What better way for children to be introduced to the world that they are to be part of than to be immersed in a story that is all about beings and the environment that surrounds them? What better way for children to learn about ideas and speech patterns, how people react and interact, and how dialogue reveals more about a person than what they say, and about interpersonal relationships. Sadly, children with reading disability have a greater tendency to develop emotional and conduct disorders needing remedial support.

Children’s Literature

It is claimed that appropriate works of children’s literature, read or enacted, help the developing children build empathy and compassion – desirable human ideals that can persist through to adult life – by placing themselves in the shoes of fictional characters and simulating what the characters in the narrative are experiencing. One could argue that the same could be achieved in real life by interacting with others but does not have the advantage of having access to the inner lives of individuals as depicted in well-crafted fictional works.

There is no better way to convey moral instruction than by vicarious learning through reading. As the legendary Russian author, Leo Tolstoy, propounded in his popular monograph, ‘What Is Art?’, the value in a piece of literary art is to be judged by its ability to make the reader morally enlightened.

There is no better way for children, while gaining the aesthetic rewards of a narrative, to enhance their thinking and reasoning, generate creativity, and introduce them to a life rich in meaning.

“There are perhaps no days of our childhood we lived fully as those we spent with a favourite book…they have engraved in us so sweet a memory, so much more precious to our present judgement than what we read then with such love…”

[‘On Reading’, by Marcel Proust 1871-1922, French novelist and literary critic]

Children’s Poetry

We are endowed with a rich poetic tradition that extends as far back as the Sinhala language and its precursors. Over the centuries the lyrical content mirrored the changing socio-cultural and political landscape of our country. During the pre-independence era, there was a revival of lyrical output from men of vision aimed at enhancing the creativity and sensibility of the young, to prepare them for the challenges of a free nation, and enhance their sensibility. Foremost among this group of poets were: ‘Tibetan’ [Sikkimese] monk, Ven. S. Mahinda, Ananda Rajakaruna and Munidasa Kumaratunga. Their poems that lured the children most were about nature. Simple and well crafted, they were designed to draw children to the lap of Mother Nature, to admire her beauty and to instil in them a lasting imagery and a feeling of tranquillity. Ananda Rajakaruna’s ‘Handa’ [the moon], ‘Tharaka’ [Stars], ‘Kurullo’ [birds], ‘Ganga’ [The river]; Rev. S. Mahinda’s ‘Samanalaya’ [The Butterfly], ‘Rathriya’ [The Night]; Munidasa Kumaratunga’s ‘Morning’, which captures the breaking dawn, ‘Ha Ha Hari Hawa’ [About the Hare], are amongst the most popular. They are best recited in the original language as any attempt at translation would seriously damage their musical and lyrical qualities.

Narrative Art

Martin Wickremasinghe [1890-1976] was ahead of his time in recognising the importance of children’s literature and its positive impact on their psychosocial and intellectual development. He argued a case for establishing a tradition of children’s literature anchored in our heritage, and in keeping with the degree of maturity of the child; and that the work be presented in a simple and pleasurable form mixed with moral instruction in the right measure. He observed that a nation without children’s literature rooted in its heritage may face intellectual and moral decline. He asserted that children’s books should only be written by those who understood the developing mind.

In his publication, ‘Apey Lama Sahithyaya’ [Our Children’s Literature] Martin Wickremasinghe acknowledges past contributions to our children’s literature by prominent writers. Piyadasa Sirisena, Munidasa Kumaratunga, G. H. Perera and others transformed folk tales into prose and poetry for children. V, D, de Lanarolle was a pioneer in writing children’s stories for supplementary reading, naming his series, ‘Vinoda Katha’ [Pleasurable Stories]. Edwin Ranawaka translated children’s stories, from English to Sinhala, to suit the local readership. Martin Wickremasinghe’s own Madol Duwa, and G. B. Senanayake’s Ranarala and Surangana Katha were significant contributions to our children’s literature. Munidasa Kumaratunga took an innovative approach in producing ‘Hath Pana’ [Seven Lives], ‘Heen Seraya’ {Slow Pace], ‘Magul Kema’ [Wedding Feast] and ‘Haawage Waga’ [The Hare’s Tale] which gained immense popularity.

Despite the above, Martin Wickremasinghe argued that we have been slow in developing children’s literature of our own, although such a literary genre has been established in the west, for example, the Aesop’s Fables and the Fairy Tales of Hans Christian Anderson.

Aesop’s Fables, thought to have been narrated by a slave who lived in ancient Greece [whose identity remains obscure in history], have survived the test of time as a conveyor of values and virtues for children to reflect on, and to generate a conversation facilitated by their teacher. The allegorical tales, much admired by children [and adults!], are aimed at both entertaining and imparting moral wisdom with the use of animal characters having human attributes [Anthropomorphism] and their social interactions. The brief and lucidly told tales – 200 or more – laden with worldly wisdom, have the potential to generate a literate population, when introduced during early childhood. Let me remind you of few popular fables with their core messages: ‘The Hare and the Tortoise’ [Slow and steady wins the race]; ‘The Lion and the Mouse’ [No act of kindness, no matter how small, is ever wasted]; ‘The Cock and the Jewel’ [The value of an object lies in the eyes of the beholder]

The Fairy [fantasy] Tales of Hans Christian Andersen [1805-1875] continues to feed the imagination of growing-up children through his portrayal of unique and unforgettable characters – witches, beasts and fairies – with features of human life. The tales of the Danish master story-teller, translated into many languages, have gained universal appeal amongst children as he weaves his vastly entertaining stories such as Thumbelina, The Tin Soldier, and The Emperor’s New Clothes etc. based on fantasies with a lesson to convey. In addition to entertainment and instruction, his tales portray universal human conditions such as joy, sorrow, fear, pride, abandonment, resoluteness etc. and allow children to recognise their own feeling states, which the psychoanalysts believe is therapeutic.

The above shows that the east and west can meet on the ground of universal values, exemplified by the arts, and that human reason – the capacity of humans to think, understand and form judgement – is the true guide in life.

In sum, although reading, writing and mathematics in early childhood education are considered the core academic literacies on which other learning rests, and on which success in life depends, current research indicates that arts education through the development of certain habits of the mind could enhance academic achievement. It is thought that high arts involvement in children tend to augment their cognitive functions [eg. attention and concentration], thinking and imaginative skills, organisational skills, reflection and evaluation, which could be ‘transferred’ to other domains of the school curriculum, including science. This is in addition to the role the arts could play in enhancing interpersonal skill and emotional well-being, in conveying moral instruction, and in the exercise of empathy. As such, one could argue a case for a well-rounded system of education incorporating the arts to be introduced during early childhood.

I apologise for my ignorance in the Arts and Literature in Tamil.

Desirable Qualities of Educators

The above ideal could only be achieved through greater investment in training competent teachers in early childhood education. What ought to be the desirable qualities of an early childhood educator? It is my view that the teacher should a] have a good understanding of childhood development – physical, psychological and intellectual – and have the capacity to appreciate individual differences; b] possess ‘age-related’ conversational skills with the children – to listen and to allow free expression, with the aim of encouraging self-exploration of their work; c] have the ability to enhance children’s self-esteem while being able to set limits when necessary, within a framework of caring; d] understand the need to liaise with the parents; and, most of all, e] have a passion for educating children.

Educational Reform

Our nation is in need of a national policy on early childhood education as part of an overall plan on educational reform. It is expected that the powers that be will address a range of issues in planning of services: the inequity in access to Early Childhood Education; integration of early childhood education with the mainstream educational facilities; quality assurance and monitoring; and most importantly, greater investment in training of competent instructors in early childhood education, and creating opportunities for the teachers to be engaged in continuing education and peer review. It is hoped that the government will be able to create a framework for laying the groundwork for restructuring Early Childhood Education – a worthy cause in nation building.

Source Material

Winner, E. [2019]. How Art Works – A psychological Exploration. Oxford University Press.

Willingham, Daniel T. [2015]. Raising Kids Who Read. Jossey Bass – A Wiley Brand.

Wickremasinghe, Martin. [Second Edition 2015]. Apey Lama Sahithya [Our Children’s Literature]. Sirasa Publishers and Distributors.

Hans Christian Andersen. Andersen’s Fairy Tales. Wilco Publication 2020 Edition.

Aesop’s Fables. Wilco Publication 2020 Edition

[The writer is a retired Consultant Psychiatrist with a background of training in Adult General Psychiatry with accredited training in Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, in the UK. He is an alumnus of Thurstan College, Colombo, and the Faculty of Medicine, University of Peradeniya. Resident in Perth, Western Australia, he is a former Examiner to The Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Psychiatrists, and the recipient of the 2023 Meritorious Award of the RANZCP [WA Branch]]

by Dr. Siri Galhenage ✍️

sirigalhenage@gmail.com

Features

Where stone, memory and belief converge: Thantirimale’s long story of civilisation

At the northern boundry of Anuradhapura, where the Malwathu Oya curves through scrubland and forest and the wilderness of Wilpattu National Park presses close, the vast rock outcrop of Tantirimale rises quietly from the earth.

Spread across nearly 200 acres within the Mahawilachchiya Divisional Secretariat Division, this ancient monastic complex is more than a place of worship. It is a layered archive of Sri Lanka’s deep past — a place where prehistoric life, early Buddhist devotion, royal legend and later artistic traditions coexist within the same stone landscape.

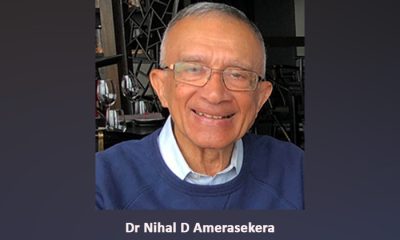

“Thantirimale is not a site that belongs to a single period,” says Dr. Nimal D. Rathnayake, one of the principal investigators who has been studying the area together with Ayoma Rathnayake and Eranga Sampath Bandara. “What we see here is continuity — people adapting to the same environment across thousands of years, leaving behind traces of belief, survival and creativity.”

Traditionally, the Thantirimale temple is believed to date back to the third century BC, placing it among the earliest Buddhist establishments in Sri Lanka.

The Mahavansa records that civilisation in this region developed following the arrival of Prince Vijaya, whose ministers were tasked with establishing settlements across the island. One such settlement, Upatissagama, founded by the minister Upatissa, is often identified as the ancient precursor to present-day Thantirimale.

Yet archaeology offers a deeper and more complex story. Excavations conducted in and around the rock shelters reveal that indigenous tribal communities lived at Thantirimale long before the rise of the Anuradhapura kingdom. These early inhabitants — likely ancestors of today’s Veddas — used the caves as dwellings, ritual spaces and meeting points thousands of years before organised monastic life took root.

“The rock shelters were not incidental,” Dr. Rathnayake explains. “They were deliberately chosen spaces — elevated, protected and close to water sources. This landscape offered everything prehistoric communities needed to survive.”

Over centuries, Thantirimale accumulated not only material remains, but also names and legends that reflect shifting political and cultural realities.

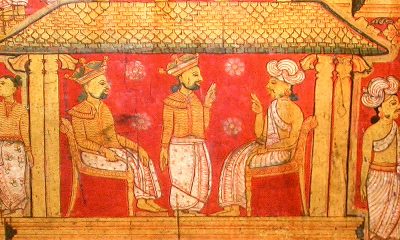

During the reign of King Devanampiyatissa, the area was known as Thivakkam Bamunugama, suggesting a Brahmin presence and ritual importance. Another strand of tradition links Thantirimale to Prince Saliya and Ashokamala, the royal lovers exiled for defying caste conventions.

Folklore holds that they lived in this region for a time, until King Dutugemunu eventually pardoned them and presented a golden butterfly-shaped necklace — the Tantiri Malaya — believed to have given the site its present name. Linguistic traditions further suggest an evolution from “Thangaathirumalai”, pointing to South Indian cultural influences.

Tantirimale also occupies a revered place in Buddhist memory. According to tradition, Sanghamitta Maha Theri rested here for a night while transporting the sacred sapling of the Jaya Sri Maha Bodhi from Jambukola to Anuradhapura. That brief pause transformed the rock into sacred ground, forever linking Tantirimale to one of the most powerful symbols of Sri Lankan Buddhism.

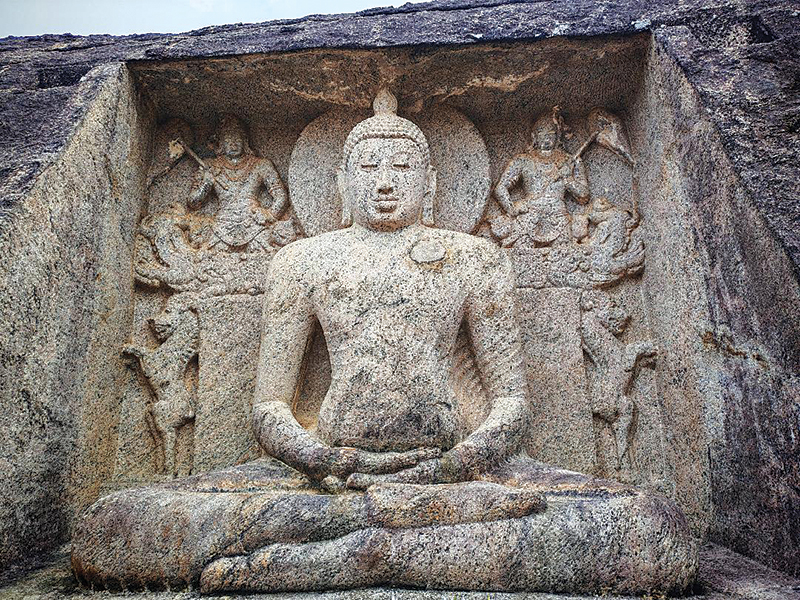

Among the most striking monuments at the site is the unfinished Samadhi Buddha statue, carved directly from a massive cube-shaped rock.

- A greater Portion of the Painted Surface of Cave NO.2

- Leatherback Sea Turtle

- The Crocodile or Land Monitor

Standing about eight feet tall, the statue bears a remarkable resemblance to the celebrated Samadhi Buddha of the Polonnaruwa Gal Viharaya. Guardian deities flank the central figure, while behind it a dragon pearl is supported by two lions — a motif associated with protection, sovereignty and cosmic balance. Dwarf figures decorate the seat, adding layers of symbolic meaning and artistic refinement.

“What is extraordinary here is the ambition of the sculpture,” says Dr. Rathnayake. “This was clearly intended to be a monumental work.” Excavations around the statue have uncovered stone pillars and evidence of a protective roof, indicating that artisans worked under shelter as they shaped the figure.

The statue’s incomplete state is most plausibly explained by the foreign invasions and political instability that marked the later Anuradhapura period. Stylistic features suggest that the work continued into, or was influenced by, the Polonnaruwa period, underscoring Thantirimale’s enduring importance long after Anuradhapura’s decline.

Nearby lies another monumental expression of devotion — the reclining Buddha statue, measuring approximately 45 feet in length. Unlike the Samadhi statue, this figure has been detached from the living rock and is dated to the late Anuradhapura period. Its scale and proportions closely resemble Polonnaruwa sculpture, reinforcing the idea of a continuous artistic and religious tradition that transcended shifting capitals and dynasties.

Yet the most ancient and fragile heritage of Thantirimale is found not in its monumental statues, but in two adjacent caves within the monastic complex. Their walls still bear the fading traces of prehistoric rock paintings dating back nearly 4,000 years. First recorded by John Still in 1909, these paintings were later documented and analysed by scholars such as Somadeva.

The paintings include human figures, animals, geometric patterns and symbolic motifs, suggesting ritual practices, storytelling and shared cultural memory. “If Tantirimale functioned as a common meeting place for independent territorial groups,” Dr. Rathnayake observes, “then these images may represent a shared visual narrative — a way of communicating identity and belief beyond spoken language.”

One of the caves, previously known to contain both human and animal figures, has deteriorated significantly and now requires urgent conservation intervention. The second cave, however, offers a rare and intriguing glimpse into prehistoric ecological awareness.

Among the animal figures are two images believed to represent a Leatherback Sea Turtle and either a crocodile or land monitor, measuring 18 and 13 centimetres respectively. The turtle depiction is particularly striking for its anatomical accuracy — the ridges on the carapace are clearly visible, aligning closely with known herpetological characteristics.

“These details suggest close observation of nature,” says Dr. Rathnayake. Archaeological evidence supports this interpretation. According to earlier studies, sea turtles were transported to Anuradhapura as early as 800 BC. During the Gedige excavations in 1985, bones of the Olive Ridley sea turtle were discovered, possibly used for ornaments or utilitarian objects. Images of land monitors and crocodiles are common in dry-zone rock art, reflecting both ecological familiarity and subsistence practices, as Veddas are known to have consumed the flesh of land monitors.

Today, Thantirimale stands at a critical crossroads. Encroaching vegetation, weathering stone, fading pigments and increasing human pressure threaten a site that encapsulates millennia of human adaptation, belief and artistic expression. For Dr. Rathnayake and his team, the need for protection is urgent.

“Thantirimale is not just an archaeological site or a temple,” he says. “It is a living record of how humans have interacted with this landscape over thousands of years. Preserving it is not simply about protecting ruins — it is about safeguarding the long memory of this island.”

In the quiet of the rock shelters, where prehistoric hands once painted turtles, hunters and symbols of meaning, Thantirimale continues to whisper its story — a story written not in ink or inscription, but in stone, pigment and belief.

By Ifham Nizam ✍️

Features

Coaching legend Susantha calls time on storied career

Veteran athletic coach Susantha Fernando called time on his illustrious career in the state service recently. Fernando, who began his career as a physical education teacher was the Assistant Director of Education (Sports and Physical Education- Central Province Sports Schools) at the time of his retirement last month.

Susantha was responsible for transforming the then little known A. Ratnayake Central, Walala, into an athletics powerhouse in the schools sports arena. His sheer commitment in nurturing the young athletes at Walala not only resulted in the sports school winning accolades at national level but also produced champions for Sri Lanka in the international arena.

These pictures are from the event to launch his autobiography Dekumkalu Kalunika and the felicitation ceremony organised by Tharanga Gunaratne, Director of Education at Wattegama Zone to felicitate him following his retirement.

Former Walala athletes, his fellow officials and a distinguished gathering including former Director of Education Sunil Jayaweera were gathered at the venue to felicitate him.

- Susantha Fernando with his family members

- Susantha with his wife, Ranjani, sons, Shane and Shamal and daughter Nethmi

- Tharanga Gunaratne, Director of Education at Wattegama Zone addressing the gathering

- Sisira Yapa, who delivered the keynote address at the book launch

- Former Director of Sports of the Ministry of Education Sunil Jayaweera

- Susantha’s first international medallist marathoner D.A. Inoka

- A dance item in progress

- Susantha Fernando with his wife Ranjani

- Susantha with his mother

-

Editorial6 days ago

Editorial6 days agoIllusory rule of law

-

Features6 days ago

Features6 days agoDaydreams on a winter’s day

-

Features6 days ago

Features6 days agoSurprise move of both the Minister and myself from Agriculture to Education

-

Features5 days ago

Features5 days agoExtended mind thesis:A Buddhist perspective

-

Features6 days ago

Features6 days agoThe Story of Furniture in Sri Lanka

-

Opinion4 days ago

Opinion4 days agoAmerican rulers’ hatred for Venezuela and its leaders

-

Features6 days ago

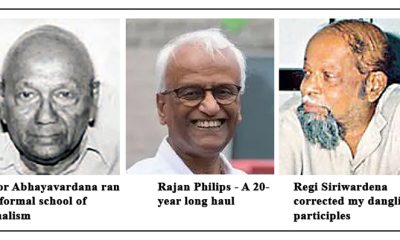

Features6 days agoWriting a Sunday Column for the Island in the Sun

-

Business2 days ago

Business2 days agoCORALL Conservation Trust Fund – a historic first for SL