Features

Martin Wickramasinghe and A.G. Fraser

By Uditha Devapriya

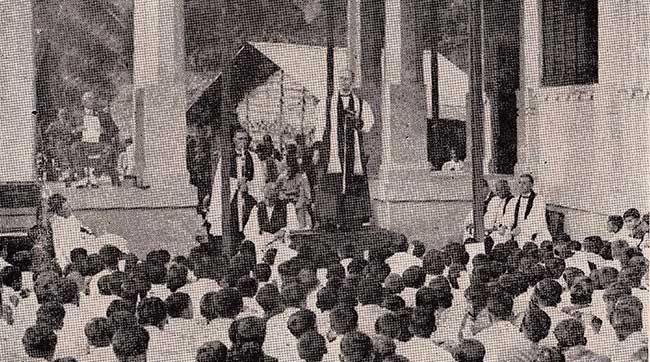

On 7 February 1970, Trinity College, Kandy held its 99th annual Prize Giving. Presided by the then Anglican Bishop of Kurunegala, Lakshman Wickremesinghe, the ceremony featured Martin Wickramasinghe as its Chief Guest. By this point Wickramasinghe had established himself as Sri Lanka’s leading literary figure. A grand old man of 80, he was now writing on a whole range of topics outside culture and literature. His essays addressed some of the more compelling socio-political issues of the day, including unrest among the youth. His speech at the Prize Giving dwelt on these issues and reflected his concerns.

On 7 February 1970, Trinity College, Kandy held its 99th annual Prize Giving. Presided by the then Anglican Bishop of Kurunegala, Lakshman Wickremesinghe, the ceremony featured Martin Wickramasinghe as its Chief Guest. By this point Wickramasinghe had established himself as Sri Lanka’s leading literary figure. A grand old man of 80, he was now writing on a whole range of topics outside culture and literature. His essays addressed some of the more compelling socio-political issues of the day, including unrest among the youth. His speech at the Prize Giving dwelt on these issues and reflected his concerns.

Wickramasinghe’s speech centred on A. G. Fraser, Principal of Trinity from 1904 to 1924. Considered one of the finest headmasters of the day, Fraser broke ground by incorporating vernacular languages to the school syllabus and indigenous cultural elements to the school environment. Fraser was 10 years into his principalship when Wickramasinghe wrote his first novel, Leela. His tenure coincided with some of the more transformative events in British Ceylon, including the McCallum and Manning constitutional reforms. His zeal, especially for indigenising Christianity and missionary education, won him as many allies as it did enemies. Eventually, it encouraged other educationists to follow suit.

The world Fraser saw through was different to the world Wickramasinghe grew up in. Yet in many ways, they were not too different. Fraser had been born to a typical colonial family: his father, Sir Andrew Henderson Leith Fraser, had served as Lieutenant-Governor of Bengal under Lord Curzon. Wickramasinghe, on the other hand, did not obtain a proper education: having left school at an early age, he had been self-educated and self-taught. Both, however, lived through an era of irreversible social transformation, and both played leading roles in that transformation. It is not clear whether the two of them ever actually met. But the two of them shared a disdain for the culture of imitativeness which had become fashionable among the colonial, Westernised middle-class. Through their fields – education in Fraser’s case, literature in Wickramasinghe’s – they strived to change that culture.

By 1970 that culture had changed, and Wickramasinghe’s contribution, as well as Fraser’s, had been widely acknowledged. It is this contribution which Wickramasinghe addressed in his speech at the Prize Giving. Hailing Fraser as a “genuine educationist”, Sri Lanka’s leading Sinhalese litterateur commended Trinity’s greatest principal’s efforts at indigenising the school and the syllabus. In doing so, he categorically refuted the allegation, popular among nationalist ideologues, that Fraser had “created a hostile attitude in the minds of the boys of Trinity to their own culture and language.” From that standpoint, he conceived an intelligent and, in my view, well-rounded critique of chauvinism, which scholars of the man have barely if at all touched in their appraisals of his work.

In a recent, intriguing essay on agrarian utopianism, Dhanuka Bandara invokes Stanley Tambiah’s claim that the concept of gama, pansala, wewa, yaya, so central to the Sinhala nationalist discourse, emerged from Martin Wickramasinghe’s work. To a considerable extent, this is true, and Dhanuka goes to great lengths to show it was. Wickramasinghe’s essays – including those on Sinhalese culture – depicts an almost pristine indigenous society, not unlike Ananda Coomaraswamy’s vision of Kandyan art and culture.

Comparisons between Wickramasinghe and Coomaraswamy are not as crude as they may appear to be. Both idealised rural Sinhalese culture, and both depicted it as an organic, tightly knit community pitted against the forces of modernity. Yet there were important differences. While Coomaraswamy, as Senake Bandaranayake’s essay on the man clearly argues, sought to preserve Kandyan art and culture throughout his life, his celebration of that culture led him to idealise a feudal, static social order. This critique, of course, can itself be critiqued, particularly by those who harbour a different view on Coomaraswamy and his work. But, in my opinion, it stands in marked contrast to Wickramasinghe’s celebration, not of cultural pristineness, but of cultural synthesis and pluralism.

Indeed, throughout his essays, Wickramasinghe hardly exudes an Arnoldian affirmation of high culture. He does not pretend to uphold a great tradition. He is concerned not with keeping intact the values of a pristine society, but with ensuring continuity and change within a certain framework and environment. Contrary to certain cultural nationalists who may imagine him to be one of them, this framework is neither exclusivist nor chauvinist. That is arguably most evident in his critiques of the vernacularisation of education in the 1950s. While admitting the need for the shift to swabasha, he criticises those who, in the guise of devising a “national” education system, went overboard in their attempts at reviving a dead, supposedly superior past in school curricula and syllabuses.

Wickramasinghe’s Trinity College speech presciently underlies these concerns. Addressing the students’ movement in the West and growing student unrest in Sri Lanka, he traces the angst of the youth to an increasingly fragmented society.

“The two causes peculiar to our country which generate discontent in the students of higher educational institutions and sometimes incite them to revolt are bureaucratic control, and the paternal attitude of the society towards them. The bureaucratic control of higher educational institutions based on foreign traditions and the class system that encouraged exploitation is an inheritance from the English colonial system. And the growth of the paternal attitude of the society to the student population is mainly due to an attempt of Buddhist monks and nationalists to revive the past with its dead culture.”

This is a remarkable observation, at odds with the conventional view of Wickramasinghe as an advocate of an organic, pristine past. He is criticising not just the English colonial system which has survived the transition to independent statehood in Sri Lanka, but also Buddhist monks and nationalists – none less! – who idealise a superior, classical culture and try to revive it everywhere. These issues, he contends, are at the centre of youth unrest, and they have pushed the young to rebel against their elders.

“The attempt to inculcate a blind and meek obedience in boys and girls for their elders and teachers is an attempt to revive the divine rights of kings. Parents deserve love, gratitude and kindness form their sons and daughters, but not surrender. What is required is not blind obedience which creates conscious and unconscious hypocrisy, but discipline on the basis of their own independent and changing culture.”

Here one is struck not merely by the author’s siding with the rebelling youth, but also by his unconditional support for their pursuit of an “independent and changing culture.” It ties in with his own belief in the inevitability of change and transformation, of the sort he and A. G. Fraser encountered and affirmed in their day. Indeed, like Fraser, Wickramasinghe critiques the colonial elite’s dismissal of national culture, yet does not embrace an exclusivist framing of this culture. “The word nationalism,” he comments, “apart from the consciousness of the cultural unity of a community, means chauvinism.” This is a remarkable observation from a man whom cultural nationalists today appropriate as one of them.

Some of his other essays from this time reveal an even more radical view on culture.

“There is a cultural unity among the common people in spite of differences of religion, language, and race. They are not interested in a state religion, communal and religious rights because they instinctively feel that there is an underlying unity in religion and race. Agitation for a state religion and communal rights emanates from a minority of educated people who have lost the ethos of their common culture.”

“Impetus for the Growth of a Multiracial Culture”

It is important to note that such views were entirely in line with A. G. Fraser’s. Fraser’s zeal for indigenisation, which inspired the two most prominent faces of Anglicanism in post-colonial Sri Lanka, Lakdasa de Mel and Lakshman Wickremesinghe, was one rooted not in the narrow frame of “Sinhala Only” and narrow communalism, but in an all-encompassing nationalism. Fraser’s intervention in the 1915 riots, derided by nationalist elites at the time, but defended eloquently by James Rutnam later, shows that to some extent.

Here, for instance, is Fraser speaking at the College Prize Giving in 1908.

“When I came here four years ago I was astonished to find that senior students who hoped to serve amongst their people could neither read nor write their own language… a thorough knowledge of the mother tongue is indispensable to true culture or real thinking power. More, a college fails if it is not producing true citizens and men who are isolated from the masses of their own people by ignorance of their language and thought can never fulfil the part of educated citizens or be the true leaders of their race.”

It would be useful to quote from Wickramasinghe’s 1970 speech.

“A child must adapt and respond to that environment of the greater society to develop his intellectual and creative faculties. If he is trained to adapt and respond only to the environment of his family circle who are mere imitators, the development of his intellectual and creative faculties will be retarded.”

Both Fraser and Wickramasinghe, in other words, are affirming the need for a child to grow amidst his environment, to learn from and absorb it, to adapt to it.Wickramasinghe’s Trinity College speech needs to be reassessed and reappraised. It distils his views on education and indigenous culture, and his critique of extremist and exclusivist variants of cultural nationalism. It is one of the best sources we have on the man’s views on these issues, and it needs to be placed in the context of its time: a year or so after the Prize Giving, Sri Lanka would encounter a widespread youth insurrection, the likes of which it had never encountered before. Martin Wickramasinghe would pass away six years after the Prize Giving, almost 15 years after Fraser’s passing. Fraser’s contribution, and Wickramasinghe’s affirmation of it, underlies a vision of nationalism and culture that was more inclusive, more diverse, and thus more representative of our country and our people.

The writer is an international relations analyst, researcher, and columnist who can be reached at udakdev1@gmail.com.

Features

RuGoesWild: Taking science into the wild — and into the hearts of Sri Lankans

At a time when misinformation spreads so easily—especially online—there’s a need for scientists to step in and bring accurate, evidence-based knowledge to the public. This is exactly what Dr. Ruchira Somaweera is doing with RuGoesWild, a YouTube channel that brings the world of field biology to Sri Lankan audiences in Sinhala.

“One of my biggest motivations is to inspire the next generation,” says Dr. Somaweera. “I want young Sri Lankans to not only appreciate the amazing biodiversity we have here, but also to learn about how species are studied, protected, and understood in other parts of the world. By showing what’s happening elsewhere—from research in remote caves to marine conservation projects—I hope to broaden horizons and spark curiosity.”

Unlike many travel and wildlife channels that prioritise entertainment, RuGoesWild focuses on real science. “What sets RuGoesWild apart is its focus on wildlife field research, not tourism or sensationalised adventures,” he explains. “While many travel channels showcase nature in other parts of the world, few dig into the science behind it—and almost none do so in Sinhala. That’s the niche I aim to fill.”

Excerpts of the Interview

Q: Was there a specific moment or discovery in the field that deeply impacted you?

“There have been countless unforgettable moments in my 20-year career—catching my first King cobra, discovering deep-diving sea snakes, and many more,” Dr. Somaweera reflects. “But the most special moment was publishing a scientific paper with my 10-year-old son Rehan, making him one of the youngest authors of an international peer-reviewed paper. We discovered a unique interaction between octopi and some fish called ‘nuclear-forager following’. As both a dad and a scientist, that was an incredibly meaningful achievement.”

Saltwater crocodiles in Sundarbans in Bangladesh, the world’s largest mangrove

Q: Field biology often means long hours in challenging environments. What motivates you to keep going?

“Absolutely—field biology can be physically exhausting, mentally draining, and often dangerous,” he admits. “I’ve spent weeks working in some of the most remote parts of Australia where you can only access through a helicopter, and in the humid jungles of Borneo where insects are insane. But despite all that, what keeps me going is a deep sense of wonder and purpose. Some of the most rewarding moments come when you least expect them—a rare animal sighting, a new behavioural observation, or even just watching the sun rise over a pristine habitat.”

Q: How do you balance scientific rigour with making your work engaging and understandable?

“That balance is something I’m constantly navigating,” he says. “As a scientist, I’m trained to be precise and data-driven. But if we want the public to care about science, we have to make it accessible and relatable. I focus on the ‘why’ and ‘wow’—why something matters, and what makes it fascinating. Whether it’s a snake that glides between trees, a turtle that breathes through its backside, or a sea snake that hunts with a grouper, I try to bring out the quirky, mind-blowing parts that spark curiosity.”

Q: What are the biggest misconceptions about reptiles or field biology in Sri Lanka?

“One of the biggest misconceptions is that most reptiles—especially snakes—are dangerous and aggressive,” Dr. Somaweera explains. “In reality, the vast majority of snakes are non-venomous, and even the venomous ones won’t bite unless they feel threatened. Sadly, fear and myth often lead to unnecessary killing. With RuGoesWild, one of my goals is to change these perceptions—to show that reptiles are not monsters, but marvels of evolution.”

Q: What are the most pressing conservation issues in Sri Lanka today?

“Habitat loss is huge,” he emphasizes. “Natural areas are being cleared for housing, farming, and industry, which displaces wildlife. As people and animals get pushed into the same spaces, clashes happen—especially with elephants and monkeys. Pollution, overfishing, and invasive species also contribute to biodiversity loss.”

Manta Rays

Q: What role do local communities play in conservation, and how can scientists better collaborate with them?

“Local communities are absolutely vital,” he stresses. “They’re often the first to notice changes, and they carry traditional knowledge. Conservation only works when people feel involved and benefit from it. We need to move beyond lectures and surveys to real partnerships—sharing findings, involving locals in fieldwork, and even ensuring conservation makes economic sense to them through things like eco-tourism.”

Q: What’s missing in the way biology is taught in Sri Lanka?

“It’s still very exam-focused,” Dr. Somaweera says. “Students are taught to memorize facts rather than explore how the natural world works. We need to shift to real-world engagement. Imagine a student in Anuradhapura learning about ecosystems by observing a tank or a garden lizard, not just reading a diagram.”

Q: How important is it to communicate science in local languages?

“Hugely important,” he says. “Science in Sri Lanka often happens in English, which leaves many people out. But when I speak in Sinhala—whether in schools, villages, or online—the response is amazing. People connect, ask questions, and share their own observations. That’s why RuGoesWild is in Sinhala—it’s about making science belong to everyone.”

‘Crocodile work’ in northern Australia.

Q: What advice would you give to young Sri Lankans interested in field biology?

“Start now!” he urges. “You don’t need a degree to start observing nature. Volunteer, write, connect with mentors. And once you do pursue science professionally, remember that communication matters—get your work out there, build networks, and stay curious. Passion is what will carry you through the challenges.”

Q: Do you think YouTube and social media can shape public perception—or even influence policy?

“Absolutely,” he says. “These platforms give scientists a direct line to the public. When enough people care—about elephants, snakes, forests—that awareness builds momentum. Policymakers listen when the public demands change. Social media isn’t just outreach—it’s advocacy.”

by Ifham Nizam

Features

Benjy’s vision materalises … into Inner Vision

Bassist Benjy Ranabahu is overjoyed as his version of having his own band (for the second time) is gradually taking shape.

Bassist Benjy Ranabahu is overjoyed as his version of having his own band (for the second time) is gradually taking shape.

When asked as to how the name Inner Vision cropped up, Benjy said that they were thinking of various names, and suggestions were made.

“Since we have a kind of a vision for music lovers, we decided to go with Inner Vision, and I guarantee that Inner Vision is going to be a band with a difference,” said Benjy.

In fact, he has already got a lineup, comprising musicians with years of experience in the music scene.

Benjy says he has now only to finalise the keyboardist, continue rehearsing, get their Inner Vision act together, and then boom into action.

“Various names have been suggested, where the keyboard section is concerned, and very soon we will pick the right guy to make our vision a reality.”

Inner Vision will line-up as follows…

Anton Fernando

Benjy Ranabahu:

Ready to give music

lovers a new vision

(Lead guitar/vocals): Having performed with several bands in the past, including The Gypsies, he has many years of experience and has also done the needful in Japan, Singapore, Dubai, the Maldives, Zambia, Korea, New Zealand, and the Middle East.

Lelum Ratnayake

(Drums/vocals): The son of the legendary Victor Ratnayake, Lelum has toured Italy, Norway, Japan, Australia, Zambia, Kuwait and Oman as a drummer and percussionist.

Viraj Cooray

(Guitar/vocals): Another musician with years of experience, having performed with several of our leading outfits. He says he is a musician with a boundless passion for creating unforgettable experiences, through music.

Nish Peiris

Nish Peiris: Extremely talented

(Female vocals): She began taking singing, seriously, nearly five years ago, when her mother, having heard her sing occasionally at home and loved her voice, got her involved in classes with Ayesha Sinhawansa. Her mom also made her join the Angel Chorus. “I had no idea I could sing until I joined Angle Chorus, which was the initial step in my career before I followed my passion.” Nish then joined Soul Sounds Academy, guided by Soundarie David. She is currently doing a degree in fashion marketing.

And … with Benjy Ranabahu at the helm, playing bass, Inner Vision is set to light up the entertainment scene – end May-early June, 2025.

Features

Can Sri Lanka’s premature deindustrialisation be reversed?

As politicians and economists continue to proclaim that the Sri Lankan economy has achieved ‘stability’ since the 2022 economic crisis, the country’s manufacturing sector seems to have not got the memo.

As politicians and economists continue to proclaim that the Sri Lankan economy has achieved ‘stability’ since the 2022 economic crisis, the country’s manufacturing sector seems to have not got the memo.

A few salient points need to be made in this context.

First, Sri Lankan manufacturing output has been experiencing a secular stagnation that predates external shocks, such as the pandemic and the Easter Attacks. According to national accounts data from UNIDO, manufacturing output in dollar terms has basically flatlined since 2012. Without a manufacturing engine at its core, it is no surprise that Sri Lanka has seen some of the lowest rates of economic growth during this period. (See graph)

Second, factory capacity utilisation still remains below pre-pandemic levels. Total capacity utilisation stood at 62% in 2024, compared to 81% in 2019. For wearing apparel, the country’s main manufactured export, capacity utilisation was at a meagre 58% in 2024, compared to 83% in 2019. Given the uncertainty Trump’s tariffs have cast on global trade, combined with the diminished consumer sentiment across the Global North, it is hard to imagine capacity utilisation recovering to pre-pandemic levels in the near future.

Third, new investment in manufacturing has been muted. From 2019 to 2024, only 26% of realised foreign investments in Board of Investment enterprises were in manufacturing. This indicates that foreign capital does not view the country as a desirable location for manufacturing investment. It also reflects a global trend – according to UNCTAD, 81% of new foreign investment projects, between 2020 and 2023, were in services.

Taken together, these features paint an alarming picture of the state of Sri Lankan manufacturing and prospects for longer-term growth.

What makes manufacturing so special?

A critical reader may ask at this point, “So what? Why is manufacturing so special?”

Political economists have long analysed the transformative nature of manufacturing and its unique ability to drive economic growth, generate technical innovation, and provide positive spillovers to other sectors. In the 1960s, Keynesian economist Nicholas Kaldor posited his famous three ‘growth laws, which argued for the ‘special place’ of manufacturing in economic development. More recently, research by UNIDO has found that 64% of growth episodes in the last 50 years were fuelled by the rapid development of the manufacturing sector.

Manufacturing profits provide the basis on which modern services thrive. London and New York could not have emerged as financial centres without the profits generated by industrial firms in Manchester and Detroit, respectively. Complex and high-end services, ranging from banking and insurance to legal advisory to logistics and transport, rely on institutional clients in industrial sectors. Meanwhile, consumer-facing services, such as retail and hospitality, depend on the middle-class wage base that an industrial economy provides.

Similarly, technologies generated in the manufacturing process can have massive impacts on raising the productivity of other sectors, such as agriculture and services. Indeed, in most OECD countries, manufacturing-oriented private firms are the biggest contributors to R&D spending – in the United States, 57% of business enterprise R&D spending is done by manufacturing firms; in China it is 80%.

It has become increasingly clear to both scholars and policymakers that national possession of industrial capacity is needed to retain advantages in higher value-added capabilities, such as design. This is because some of the most critical aspects of innovation are the ‘process innovations’ that are endemic to the production process itself. R&D cannot always be done in the comfort of an isolated lab, and even when it can, there are positive spillovers to having geographic proximity between scientists, skilled workers, and industrialists.

Produce or perish?

Sri Lanka exhibits the telltale signs of ‘premature deindustrialisation’. The term refers to the trend of underdeveloped countries experiencing a decline in manufacturing at levels of income much lower than what was experienced by countries that managed to break into high-income status.

Premature deindustrialisation afflicts a range of middle-income countries, including India, Brazil, and South Africa. It is generally associated with the inability of domestic manufacturing firms to diversify their activities, climb up the value chain, and compete internationally. Major bottlenecks include the lack of patient capital and skilled personnel to technologically upgrade and the difficulties of overcoming the market power of incumbents.

Reversing the trend of premature deindustrialisation requires selective industrial policy. This means direct intervention in the national division of labour in order to divert resources towards strategic sectors with positive spillovers. Good industrial policy requires a carrot-and-stick approach. Strategic manufacturing sectors must be made profitable, but incentives need to be conditional and based on strict performance criteria. Industrial can choose winners, but it has to be willing to let go of losers.

During the era of neoliberal globalisation, the importance of manufacturing was underplayed (or perhaps deliberately hidden). To some extent, knowledge of its importance was lost to policymakers. Karl Marx may have predicted this when, in Volume 2 of Das Kapital, he wrote that “All nations with a capitalist mode of production are, therefore, seized periodically by a feverish attempt to make money without the intervention of the process of production.”

Since the long depression brought about by the 2008 financial crisis, emphasis on manufacturing is making a comeback. This is most evident in the US ruling class’s panic over China’s rapid industrialisation, which has shifted the centre of gravity of the world economy towards Asia and threatened unipolar dominance by the US. In the Sri Lankan context, however, emphasis on manufacturing remains muted, especially among establishment academics and policy advisors who remain fixated on services.

Interestingly, between the Gotabaya Rajapaksa-led SLPP and the Anura Kumara Dissanayake-led NPP, there is continuity in terms of the emphasis on the slogan of a ‘production economy’ (nishpadana arthiakaya in Sinhala). Perhaps more populist than strictly academic, the continued resonance of the slogan reflects a deep-seated societal anxiety about Sri Lanka’s ability to survive as a sovereign entity in a world characterised by rapid technological change and the centralisation of capital.

Nationalist writer Kumaratunga Munidasa once said that “a country that does not innovate will not rise”. Amid the economic crises of the 1970s, former Prime Minister Sirimavo Bandaranaike popularised a pithier exhortation: “produce or perish”. Aside from their economic benefits, manufacturing capabilities are the pride of a nation, as they demonstrate skill and scientific knowledge, a command over nature, and the ability to mobilise and coordinate people towards the construction of modern wonders. In short, it is hard to speak of real sovereignty without modern industry.

(Shiran Illanperuma is a researcher at Tricontinental: Institute for Social Research and a co-Editor of Wenhua Zongheng: A Journal of Contemporary Chinese Thought. He is also a co-Convenor of the Asia Progress Forum, which can be contacted at asiaprogressforum@gmail.com).

By Shiran Illanperuma

-

Business3 days ago

Business3 days agoDIMO pioneers major fleet expansion with Tata SIGNA Prime Movers for ILM

-

News2 days ago

News2 days agoFamily discovers rare species thought to be extinct for over a century in home garden

-

Features5 days ago

Features5 days agoNipping the two leaves and the bud

-

Features4 days ago

Features4 days agoProf. Lal Tennekoon: An illustrious but utterly unpretentious and much -loved academic

-

Features5 days ago

Features5 days agoAvurudu celebrations … galore

-

Foreign News3 days ago

Foreign News3 days agoChina races robots against humans in Beijing half marathon

-

Latest News7 days ago

Latest News7 days agoTrump freezes $2bn in Harvard funding after university rejects demands

-

News5 days ago

News5 days agoCounsel for Pilleyan alleges govt. bid to force confession