Features

Manourie Muttetuwegama, a personal memoir

by Manik de Silva

My grandfather, the late Dr. O.A. de Silva of Sisira, Randombe, Ambalangoda, chose two phonetically similar but fairly uncommon names for his two elder sons. My father was Walwin Arnold and loku baappa was Colvin Reginald. Colvin married much earlier than thaththa and thus all three of his children were older than my parents’ five.

The brood at Pendennis Avenue (now Abdul Caffoor Mawatha), Kollupitiya, were Manouri Kokila, Shireen Mohini and Nalina Visvajit. None of them, however, were ever called by their given names. Manouri was Toonie (sometimes Toonie Man or TM to her father), Shireen was Podi Toot (often PT to Colvin) and NV was Koiman (but never KM). None of us cousins (22 in all on our paternal side) ever figured out or learned how or why these nicknames were coined. So Manouri – a most unusual name then and possibly the progenitor off all Manouris (or Manoris who came since) was always Toonie akka to all her cousins.

The nicknames were not the only difference between us cousins. Colvin’s children called their parents mummy and daddy while to the rest of us, our’s were amma and thaththa. The children of that family, as I remember, had more liberties than us due to Colvin’s easy going nature and very busy professional and political life. Perhaps kudamma was less indulgent notwithstanding her kindness and hospitality. My father was the only person who, as I recall, she did not serve at her table because he had made it very clear that he must serve himself!

Manouri was both an extremely attractive child and later a beautiful woman who, her father, particularly, doted on. So also did her grandfathers on both sides. Both grandmothers died early. I clearly remember loku bappa once taking her to England as a child, maybe he wanted to to show off his daughter to his British friends (Both Walwin and Colvin were educated at the London University after a brief stint at the then University College here). When they returned, loku bappa with his penchant for a good story, used to regale us with their experiences on that trip. One I vividly recall was “whenever we went to a restaurant, Toonie’s eye unerringly went to the most expensive dish on the menu.”

Very few remember the tragedies Toonie akka went through during her 85 years, She bore them all stoically, never brooded over misfortunes and always presented a cheerful face to the world. Little known is the accident she suffered on her bicycle either as a child or early teen. She had cycled to our home on Charles Way and was going back to Pendennis Avenue when she was hit by an overtaking car on the Galle Road and was unconscious for 14 days. It was “touch and go” as her brother reminded me after her death.

He also told me a story I did not know before. Kudamma was at her bedside when Toonie akka regained consciousness. Perhaps having being vaguely aware of those nursing her during her coma, she had asked “Why are you wearing my mother’s clothes?” when she opened her eyes, having mistaken her mother for one of the nurses. I remember as a child counting the days of Toonie akka lying unconscious on a hospital bed. It was a traumatic time for the whole family but she soon bounced back fully recovered.

She was one of the two cleverest girls a Visakha Vidyalaya of her time. The other was Kumari Wickramasuriya, my mother’s eldest sister’s daughter. I remember her and Toonie akka in the early fifties going together in a six-member contingent for a Girl Guide event in Australia. Four of the girls in that group were from Visakha. I also remember viewing a Visakha school play in which Toonie akka was acting, playing the part of a king, when she dropped her crown on stage. Not for her the indignity of bending down to retrieve it. She laughingly ad libbed a line clean off the script by describing herself as “a king without a crown!” We all thought that was brilliant.

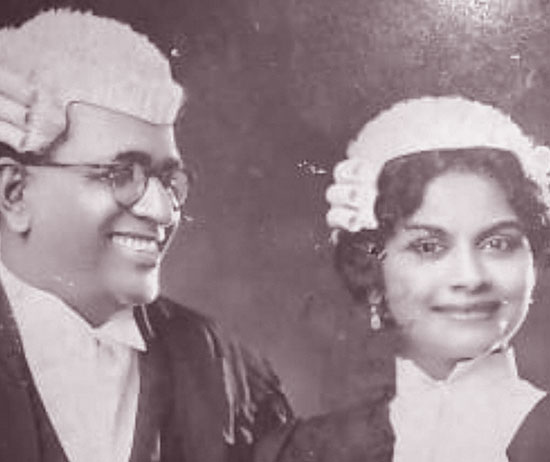

Her parents, undoubtedly anxious too see her qualify as a barrister like her father sent her to the UK after she had completed her secondary education. She was called to the bar at Lincoln’s Inn like her father before her and her brother and daughter after.

Koiman too was shipped off to London for law studies although he always had a penchant for mechanical engineering (and still does). His mother wouldn’t hear of him doing anything but law and Colvin, sadly, did not intervene. Koiman practiced his profession very briefly and has remained a non-practicing advocate/barrister for most of his life. International phone calls were few and far between in those days and I recall one to Toonie akka on one rare occasion, when she said she was busy cooking a pork chop for her brother. For the past several years, after his return to then Ceylon, he’s been a very strict vegetarian and no fish, flesh or fowl is permitted in his house.

I mentioned earlier here that Toonie akka, in her lifetime, took several body blows which would have felled lesser mortals. She was only two years old when Colvin was jailed under the colonial Defence of India Regulations, broke jail and went underground in India for four years. That was a traumatic time for the young family. After her bicycle accident, the second blow struck when Sarath Muttetuwegama, whom she married was killed in a motor car accident near Ratnapura in1986. Then she tragically lost their son, Maithri, a few years later. Thereafter she was diagnosed with cancer.

I remember going to Sarath’s ancestral home at Kuruwita after his tragic death. Toonie akka hugged me, and told me, “Malli, when I was small, mummy took me to K.C. Nadarajah’s (a well known lawyer of the day) home where there was a vakyam (ola leaf) reader from India. He read mine and told me ‘you will have a very happy marriage for 19 years and after that what…’ He didn’t say what that what was then, but it’s now 19 years since we married.” Perhaps she believed that Sarath’s death was foreordained.

There was also a time when Sarath, then a proctor who later qualified as an advocate, was engaged to Manouri when Colvin saw him on his feet in a courtroom. He told me: “I’m not saying this because he’s marrying my daughter, but his cross-examination was exceptional.” Sarath did as well in his profession as a criminal lawyer as he did in politics – among the best parliamentarians I’ve seen during long years as a lobby correspondent. He was much loved in the Sabaragamuwa Province where he was Sarath appo to the people. Prime Minister Premadasa once publicly said, perhaps to dig at Anura B, “Sarath Muttetuwegama is the real Leader of the Opposition, not Anura Bandaranaike.”

During her later years Toonie akka suffered an accident at the Yala National Park when she was in the deep south on human rights work. Her finger accidentally caught in a deck chair strut as she sat down, and part of it got sliced off. She was taken to the Tissamaharama hospital with the slice digit in ice in a sirisiri bag and later rushed to Colombo. But reattachment was not possible and she lived with that for the rest of her life. In those years she walked with a stick with great panache. She had inherited a lot of her father’s mannerism but not his booming voice. She never failed to ring me up and congratulate me on the paper I now edit whenever she had enjoyed an issue, and that was often.

It may be worth retelling an anecdote relating to her life and mine. That happened when she took an Ll.M. degree from London University after her first degree. I was then a raw cub reporter on the old Ceylon Observer. Her maternal uncle (mother’s brother), Dr. S.L. de Silva (husband of the well known educator Dr. Wimala de Silva), then Director of the Ceylon Technical College, phoned me and said I should write a paragraph of Manouri being the first Ceylonese woman to earn an Ll.M. degree. I wrote a news paragraph front-paged in the Sunday Observer.

When I went to work next morning, a woman subeditor on our staff said I had published a false claim and mentioning another lady lawyer who she said had an LlM, I was terrified. My editor, the redoubtable Denzil Pieris, called me up and said the subeditor concerned had complained to him and was spreading the story around the office. He said had told her that if there was a valid complaint, he should be told so by letter. “Manouri’s Colvin’s daughter. I bet I’ll never get that letter,” Denzil said. “In any case that degree was from an American University called Colgate which to us here is a brand of toothpaste!” he told me to my great relief.

A little known part of her life was that she was a temple-goer. Sunil Rodrigo, chairman of the Associated Newspapers of Ceylon Ltd. (ANCL) during my Daily News days, who lived on Isipathana Mawatha, once told me that his wife, Thilaka, was deeply impressed seeing Toonie akka walk to the Isipathanaramaya off and on. Mrs. Rodrigo didn’t associate somebody like Manourie with temple going.

Let me conclude this narrative with the time Lake House paid me to resign, having moved me out of my job as editor of the Daily News for14 years to a ‘nothing to do’ position as the company’s editorial consultant about a year earlier. I was kept twiddling my thumbs doing nothing and spent my time writing articles for the foreign press. But that’s another story. Toonie akka was then on the Lake House board and she told me that the then Media Minister, Mangala Samaraweera, who wanted me out, did not know our connection.

“I told him you were my malli,” she said but that was to no avail. She also told me that the then chairman and another director used to whisper to each other, keeping her out of the conversation when my dismissal was discussed at board meetings. So I left Lake House after nearly 40 years of service when Manouri was on the board of ANCL, then under government control. It turned out best for me, given that I was paid to go rather than having to work under conditions which would have certainly compelled my resignation.