Features

Lester and Ceylon Theatres : The Peak of a career

By Uditha Devapriya

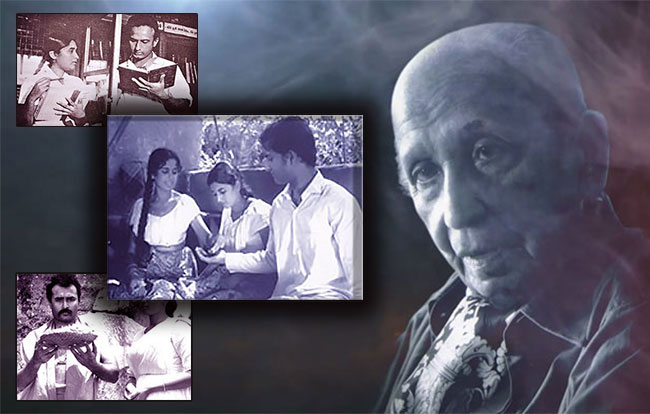

The three films that Lester James Peries directed for Ceylon Theatres – Golu Hadawatha (1968), Akkara Paha (1969), and Nidhanaya (1970) – stand out among the finest ever made in this country. They are an affirmation of life, sweeping epic-like fables that seem to tell us about ourselves, who we are and how we live. When Ceylon Theatres commissioned Peries to take on these projects, it was allegedly on the verge of bankruptcy. As he recalled for A. J. Gunawardena many, many years later, the company had reached a point where it preferred serious, low budget productions to expensive box-office flops.

The trilogy marked Peries’s second foray into a production financed by a mainstream studio. The first was, of course, Sandeshaya, produced by K. Gunaratnam. But Sandeshaya was of a totally different calibre, mainstream and conventional in the best sense of those terms. From an artistic point of view, his reimagining of a Sinhalese uprising against Portuguese rule left much to be desired, though it broke box-office records and found a ready audience in the Soviet Union. It introduced Gamini Fonseka to the screen, topping even the real hero of the story, played by Ananda Jayaratne. It also established Peries’s reputation as someone who could be trusted with a large, lavish production.

His work for Ceylon Theatres did not involve such a production. The situation was such that by that time, the mainstream studio system in the country was falling apart. The State was playing a more interventionist role in the film industry, promoting local productions over the imported variety. This had a profound effect on the studios, forcing them to revise their strategies. At the beginning of the decade, it would have been difficult to imagine a major production company hiring someone like Lester to do not one, not two, but three films in a row: Lester himself has recounted, many times, that while making Gamperaliya the studios effectively blacklisted his crew, refusing to lend them lighting equipment.

By 1968 Lester had earned an unenviable epithet for himself: he had become, in the words of his detractors, a “prestige failure.” On this point he is often compared to Satyajit Ray. But Ray worked within a different frame and a different culture: notwithstanding his refusal to make concessions to the box-office, Ray enjoyed a wider, more diverse market, in which it was possible to sustain an art-house and a commercial film industry at the same time. In Sri Lanka the issue was that even popular films, made by the big studios, were losing money. One of Peries’s friends, the producer P. E. Anthonypillai, had persuaded the Ceylon Theatres Board that “it was better policy to attempt some serious productions.”

The Sinhala film industry has always encountered, or suffered from, a tenuous relationship between cinema and literature, and often the theatre. Most of the early films – including the first, Kadawunu Poronduwa (1947) – were based on novels and plays, if not historical epics which themselves had been adapted as novels and plays. Ornate, decorative, and not a little tawdry, the tenor and mood of these works rang false, and adapted to the screen, they seemed twice or thrice removed from the realities of life. That most of these productions had been shot in the Madras studios reinforced these qualities, particularly with the use of audio-visual elements that were, if not Indian, then evocative of Indian life. Mervyn de Silva no doubt had this in mind when he called Rekava the first Sinhalese film.

By the time Lester James Peries entered the stage in 1956, things had begun to change. Literature and theatre, once laden with high-flown dialogues and ornate landscapes, had become more naturalised. Even Ediriweera Sarachchandra’s attempts at stylised theatre seemed, at least with Maname and Sinhabahu, the twin peaks of his career, truer to life than the John de Silva plays. If Martin Wickramasinghe had spearheaded a revolution in literature in 1947, with Gamperaliya, he completed it in 1956 with Viragaya, and in 1957 with Kaliyugaya, the latter being in my opinion his finest novel. Elsewhere writers like G. B. Senanayake and dramatists like Gunasena Galappatti were experimenting with different styles. The result was an efflorescence of the arts.

In other words, the cultural revolution which led from 1956, and in a way also preceded it, provided a rich storehouse of material for Peries’s films. Meeting Martin Wickramasinghe for the first time, Peries reportedly told him that with the resources of the cinema even a directory could be turned into a film. Wickramasinghe had come from a generation that saw cinema purely as escapist entertainment: his film reviews, including a particularly acerbic one of Asokamala which he charges as having corrupted history, show that he didn’t think of the medium highly. Yet by pioneering a revolution in the arts, he unleashed a paradigm shift in the cinema. It was this which Lester took up, starting with Gamperaliya, the first authentic film – “full of Chekhovian grace” as Lindsay Anderson called it – made here.

These adaptations – and there were many of them in Lester’s career – worked best when the director approached the material from a cinematic rather than an originalist standpoint. What do I mean by “originalist”? I mean that attitude which encourages scriptwriters and filmmakers to literally transpose a novel or a play. Neither Lester nor Regi Siriwardena, his screenwriter and in my opinion the finest screenwriter this country ever produced, went for such an approach with Gamperaliya. Aided in no small part by Tissa Abeysekara, Peries and Siriwardena cut away everything but the barest essentials of the story, which centre on the romance between Piyal and Nanda. Everything else, including Nanda’s brother Tissa’s forays in the city and a side-plot involving Laisa, were removed from the script.

Lester’s next two films – Delovak Athara (1966) and Ran Salu (1967) – are in many ways interconnected. Both were based on original screenplays, though the latter was based on a story P. K. D. Seneviratne wrote for Punya Heedeniya. Both feature Tony Ranasinghe, J. B. L. Gunasekera, and Irangani Serasinghe and both are set in Colombo. They almost seem like an interregnum in Lester’s first few years, though both are, without exception, very finely done and directed. These confirmed his reputation as a prestige failure, even though Ran Salu, no doubt because of its Buddhist and traditionalist theme, became a box-office success. They also established him as a man who could be trusted, and encouraged the justifiably cautious Board at Ceylon Theatres to take him in at P. E. Anthonypillai’s bidding.

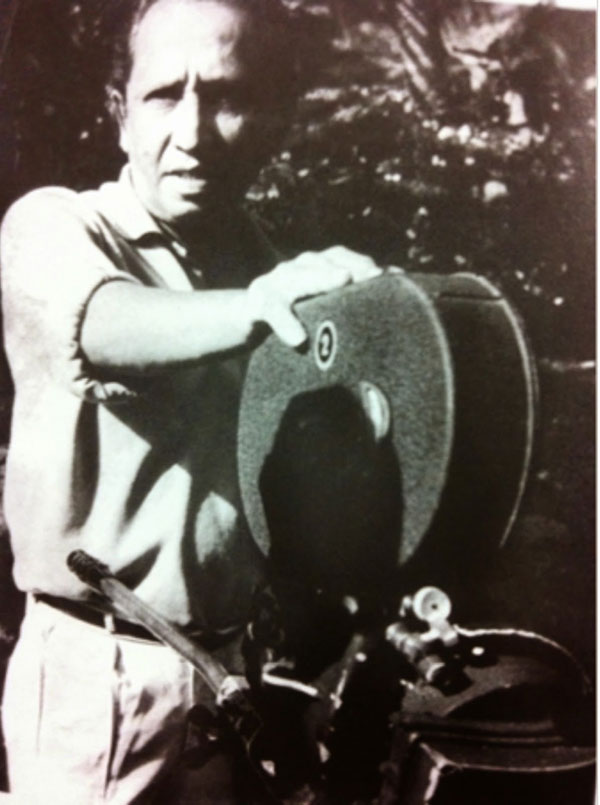

Ceylon Theatres had more or less granted Lester his benediction. Though he had to put up with various constraints – he couldn’t hire his own crew, and even the work he and his wife, Sumitra Gunawardena, supervised, had to be shared, at least in the opening credits, with the studio technicians – he was given “full control over story, script music, editing.” This was a dream come true: the opportunity and carte blanche to do what he wanted. Yet mindful of his responsibilities, he sought to insure himself against box-office failure, something which would obviously have gone against him. With this in view, he opted for a literary “property” which “seemed to go against the grain of his previous work.”

For his first film he went for a middle-brow romance, written by someone who a critic – I think Regi Siriwardena – once fittingly described as having bridged the gap between Martin Wickramasinghe and Sinhala pulp fiction. Karunasena Jayalath’s novels read so smoothly that you can almost quote them from memory. Unlike the later generation of pulp writers, his words rang true to life, because many of these stories were based on his own life. Golu Hadawatha was certainly inspired by his adolescent encounters. It was a clean break from Gamperaliya, and it marked a turning point in Lester’s career. In this he was aided by two of his most frequent collaborators: Siriwardena, who took the dialogues from the novel and turned out the script almost overnight, and Sumitra, who did wonders with the editing and cut the film twice: “first to the narration, then to the musical score.”

The result was one of the finest films ever made in the country. I have written elsewhere about the merits of Golu Hadawatha, and I think from all those qualities I saw in the story, the most striking would have to be the director’s perception of a social class he had never really depicted until then: the rural petty bourgeoisie. Golu Hadawatha is essentially about an interlude between two rural Sinhala Buddhist middle-class lovers, who are tied to their cultural-traditionalist roots but yearn to break away from those ties. How Peries manages to capture this, through the skilful yet highly underrated performances of Wickrema Bogoda and Anula Karunatilake, cannot really be described in words.

The film remains, then as now, an abiding promise of what love means, and more importantly of what a director reputed for high artistic standards could achieve if he were given the money and the resources. It is as much an affirmation of love and life, then, as it is of a visionary’s career.The writer is an international relations analyst, researcher, and columnist who can be reached at udakdev1@gmail.com

Features

Recruiting academics to state universities – beset by archaic selection processes?

Time has, by and large, stood still in the business of academic staff recruitment to state universities. Qualifications have proliferated and evolved to be more interdisciplinary, but our selection processes and evaluation criteria are unchanged since at least the late 1990s. But before I delve into the problems, I will describe the existing processes and schemes of recruitment. The discussion is limited to UGC-governed state universities (and does not include recruitment to medical and engineering sectors) though the problems may be relevant to other higher education institutions (HEIs).

How recruitment happens currently in SL state universities

Academic ranks in Sri Lankan state universities can be divided into three tiers (subdivisions are not discussed).

* Lecturer (Probationary)

– recruited with a four-year undergraduate degree. A tiny step higher is the Lecturer (Unconfirmed), recruited with a postgraduate degree but no teaching experience.

* A Senior Lecturer can be recruited with certain postgraduate qualifications and some number of years of teaching and research.

* Above this is the professor (of four types), which can be left out of this discussion since only one of those (Chair Professor) is by application.

State universities cannot hire permanent academic staff as and when they wish. Prior to advertising a vacancy, approval to recruit is obtained through a mind-numbing and time-consuming process (months!) ending at the Department of Management Services. The call for applications must list all ranks up to Senior Lecturer. All eligible candidates for Probationary to Senior Lecturer are interviewed, e.g., if a Department wants someone with a doctoral degree, they must still advertise for and interview candidates for all ranks, not only candidates with a doctoral degree. In the evaluation criteria, the first degree is more important than the doctoral degree (more on this strange phenomenon later). All of this is only possible when universities are not under a ‘hiring freeze’, which governments declare regularly and generally lasts several years.

Problem type 1

– Archaic processes and evaluation criteria

Twenty-five years ago, as a probationary lecturer with a first degree, I was a typical hire. We would be recruited, work some years and obtain postgraduate degrees (ideally using the privilege of paid study leave to attend a reputed university in the first world). State universities are primarily undergraduate teaching spaces, and when doctoral degrees were scarce, hiring probationary lecturers may have been a practical solution. The path to a higher degree was through the academic job. Now, due to availability of candidates with postgraduate qualifications and the problems of retaining academics who find foreign postgraduate opportunities, preference for candidates applying with a postgraduate qualification is growing. The evaluation scheme, however, prioritises the first degree over the candidate’s postgraduate education. Were I to apply to a Faculty of Education, despite a PhD on language teaching and research in education, I may not even be interviewed since my undergraduate degree is not in education. The ‘first degree first’ phenomenon shows that universities essentially ignore the intellectual development of a person beyond their early twenties. It also ignores the breadth of disciplines and their overlap with other fields.

This can be helped (not solved) by a simple fix, which can also reduce brain drain: give precedence to the doctoral degree in the required field, regardless of the candidate’s first degree, effected by a UGC circular. The suggestion is not fool-proof. It is a first step, and offered with the understanding that any selection process, however well the evaluation criteria are articulated, will be beset by multiple issues, including that of bias. Like other Sri Lankan institutions, universities, too, have tribal tendencies, surfacing in the form of a preference for one’s own alumni. Nevertheless, there are other problems that are, arguably, more pressing as I discuss next. In relation to the evaluation criteria, a problem is the narrow interpretation of any regulation, e.g., deciding the degree’s suitability based on the title rather than considering courses in the transcript. Despite rhetoric promoting internationalising and inter-disciplinarity, decision-making administrative and academic bodies have very literal expectations of candidates’ qualifications, e.g., a candidate with knowledge of digital literacy should show this through the title of the degree!

Problem type 2 – The mess of badly regulated higher education

A direct consequence of the contemporary expansion of higher education is a large number of applicants with myriad qualifications. The diversity of degree programmes cited makes the responsibility of selecting a suitable candidate for the job a challenging but very important one. After all, the job is for life – it is very difficult to fire a permanent employer in the state sector.

Widely varying undergraduate degree programmes.

At present, Sri Lankan undergraduates bring qualifications (at times more than one) from multiple types of higher education institutions: a degree from a UGC-affiliated state university, a state university external to the UGC, a state institution that is not a university, a foreign university, or a private HEI aka ‘private university’. It could be a degree received by attending on-site, in Sri Lanka or abroad. It could be from a private HEI’s affiliated foreign university or an external degree from a state university or an online only degree from a private HEI that is ‘UGC-approved’ or ‘Ministry of Education approved’, i.e., never studied in a university setting. Needless to say, the diversity (and their differences in quality) are dizzying. Unfortunately, under the evaluation scheme all degrees ‘recognised’ by the UGC are assigned the same marks. The same goes for the candidates’ merits or distinctions, first classes, etc., regardless of how difficult or easy the degree programme may be and even when capabilities, exposure, input, etc are obviously different.

Similar issues are faced when we consider postgraduate qualifications, though to a lesser degree. In my discipline(s), at least, a postgraduate degree obtained on-site from a first-world university is preferable to one from a local university (which usually have weekend or evening classes similar to part-time study) or online from a foreign university. Elitist this may be, but even the best local postgraduate degrees cannot provide the experience and intellectual growth gained by being in a university that gives you access to six million books and teaching and supervision by internationally-recognised scholars. Unfortunately, in the evaluation schemes for recruitment, the worst postgraduate qualification you know of will receive the same marks as one from NUS, Harvard or Leiden.

The problem is clear but what about a solution?

Recruitment to state universities needs to change to meet contemporary needs. We need evaluation criteria that allows us to get rid of the dross as well as a more sophisticated institutional understanding of using them. Recruitment is key if we want our institutions (and our country) to progress. I reiterate here the recommendations proposed in ‘Considerations for Higher Education Reform’ circulated previously by Kuppi Collective:

* Change bond regulations to be more just, in order to retain better qualified academics.

* Update the schemes of recruitment to reflect present-day realities of inter-disciplinary and multi-disciplinary training in order to recruit suitably qualified candidates.

* Ensure recruitment processes are made transparent by university administrations.

Kaushalya Perera is a senior lecturer at the University of Colombo.

(Kuppi is a politics and pedagogy happening on the margins of the lecture hall that parodies, subverts, and simultaneously reaffirms social hierarchies.)

Features

Talento … oozing with talent

This week, too, the spotlight is on an outfit that has gained popularity, mainly through social media.

This week, too, the spotlight is on an outfit that has gained popularity, mainly through social media.

Last week we had MISTER Band in our scene, and on 10th February, Yellow Beatz – both social media favourites.

Talento is a seven-piece band that plays all types of music, from the ‘60s to the modern tracks of today.

The band has reached many heights, since its inception in 2012, and has gained recognition as a leading wedding and dance band in the scene here.

The members that makeup the outfit have a solid musical background, which comes through years of hard work and dedication

Their portfolio of music contains a mix of both western and eastern songs and are carefully selected, they say, to match the requirements of the intended audience, occasion, or event.

Although the baila is a specialty, which is inherent to this group, that originates from Moratuwa, their repertoire is made up of a vast collection of love, classic, oldies and modern-day hits.

The musicians, who make up Talento, are:

Prabuddha Geetharuchi:

(Vocalist/ Frontman). He is an avid music enthusiast and was mentored by a lot of famous musicians, and trainers, since he was a child. Growing up with them influenced him to take on western songs, as well as other music styles. A Peterite, he is the main man behind the band Talento and is a versatile singer/entertainer who never fails to get the crowd going.

Geilee Fonseka (Vocals):

A dynamic and charismatic vocalist whose vibrant stage presence, and powerful voice, bring a fresh spark to every performance. Young, energetic, and musically refined, she is an artiste who effortlessly blends passion with precision – captivating audiences from the very first note. Blessed with an immense vocal range, Geilee is a truly versatile singer, confidently delivering Western and Eastern music across multiple languages and genres.

Chandana Perera (Drummer):

His expertise and exceptional skills have earned him recognition as one of the finest acoustic drummers in Sri Lanka. With over 40 tours under his belt, Chandana has demonstrated his dedication and passion for music, embodying the essential role of a drummer as the heartbeat of any band.

Harsha Soysa:

(Bassist/Vocalist). He a chorister of the western choir of St. Sebastian’s College, Moratuwa, who began his musical education under famous voice trainers, as well as bass guitar trainers in Sri Lanka. He has also performed at events overseas. He acts as the second singer of the band

Udara Jayakody:

(Keyboardist). He is also a qualified pianist, adding technical flavour to Talento’s music. His singing and harmonising skills are an extra asset to the band. From his childhood he has been a part of a number of orchestras as a pianist. He has also previously performed with several famous western bands.

Aruna Madushanka:

(Saxophonist). His proficiciency in playing various instruments, including the saxophone, soprano saxophone, and western flute, showcases his versatility as a musician, and his musical repertoire is further enhanced by his remarkable singing ability.

Prashan Pramuditha:

(Lead guitar). He has the ability to play different styles, both oriental and western music, and he also creates unique tones and patterns with the guitar..

Features

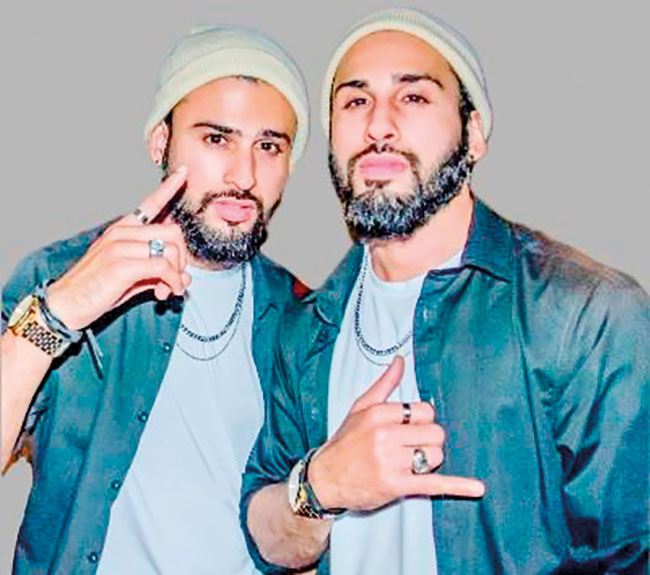

Special milestone for JJ Twins

The JJ Twins, the Sri Lankan musical duo, performing in the Maldives, and known for blending R&B, Hip Hop, and Sri Lankan rhythms, thereby creating a unique sound, have come out with a brand-new single ‘Me Mawathe.’

In fact, it’s a very special milestone for the twin brothers, Julian and Jason Prins, as ‘Me Mawathe’ is their first ever Sinhala song!

‘Me Mawathe’ showcases a fresh new sound, while staying true to the signature harmony and emotion that their fans love.

This heartfelt track captures the beauty of love, journey, and connection, brought to life through powerful vocals and captivating melodies.

It marks an exciting new chapter for the JJ Twins as they expand their musical journey and connect with audiences in a whole new way.

Their recent album, ‘CONCLUDED,’ explores themes of love, heartbreak, and healing, and include hits like ‘Can’t Get You Off My Mind’ and ‘You Left Me Here to Die’ which showcase their emotional intensity.

Readers could stay connected and follow JJ Twins on social media for exclusive updates, behind-the-scenes moments, and upcoming releases:

Instagram: http://instagram.com/jjtwinsofficial

TikTok: http://tiktok.com/@jjtwinsmusic

Facebook: http://facebook.com/jjtwinssingers

YouTube: http://youtube.com/jjtwins

-

Opinion5 days ago

Opinion5 days agoJamming and re-setting the world: What is the role of Donald Trump?

-

Features5 days ago

Features5 days agoAn innocent bystander or a passive onlooker?

-

Features2 days ago

Features2 days agoBrilliant Navy officer no more

-

Features6 days ago

Features6 days agoRatmalana Airport: The Truth, The Whole Truth, And Nothing But The Truth

-

Business7 days ago

Business7 days agoDialog partners with Xiaomi to introduce Redmi Note 15 5G Series in Sri Lanka

-

Features7 days ago

Features7 days agoBuilding on Sand: The Indian market trap

-

Opinion7 days ago

Opinion7 days agoFuture must be won

-

Opinion2 days ago

Opinion2 days agoSri Lanka – world’s worst facilities for cricket fans