Features

Lesser-known Stories from the Early Days of Sri Lankan Cinema

The Silenced Era

by Hasini Haputhanthri

(From Shared ENCOUNTERS in Myanmar, Sri Lanka and Thailand – International Centre for Ethnic Studies)

A Gentleman from Jaffna

Watching Sound of Music at Rio Cinema, Colombo was an unforgettable childhood recollection for Swarna Pathirage. “My favorite song was ‘Sixteen Going on Seventeen’ where Liesel jumps from bench to bench in the summer house with Rolf,” she says.

Swarna is now sixty-two, a matriarch , and busy with her grandchild. The memory swiftly takes her to her childhood and at the center of this memory is one Mr Dharmalingam, affectionately referred to as Dharme uncle.

Dharme uncle was a paying guest, or ‘a boarder’ in Swarna’s home for many years. They are a Sinhalese Buddhist family from Kalutara, a town two hours South of Colombo and Mr Dharmalingam was a Tamil Hindu gentleman from Jaffna. Dharme uncle was the manager of Rio Cinema, Colombo. This meant royal treatment every time the family visited Rio for a show.

“Dharme uncle always had icy chocs for us at the show. We used to eat it in the airconditioned cinema, with our teeth chattering. He used to tell us that eating ice cream in the AC actually makes you feel warmer. And it’s true!” says Swarna.

In the 1970s in Ceylon, the world’s first woman premier, Mrs. Sirima Bandaranaike was back in power for a second term, and driving even more radical policies; nationalizing industries, pursuing land reforms, restricting imports and changing the constitution and the name of the island from Ceylon to Sri Lanka.

After a while, Dharme uncle married and moved away. “We didn’t have telephones those days. So, we lost touch.” There’s a hint of regret in Swarna’s admission.

Things got much worse in Sri Lanka in the 1980s. It explains why the family perhaps did not keep in touch with their friend. The island nation with a majority Sinhalese Buddhist population sank into a quagmire of ethnic conflict, racism and corruption, the consequences of which are being experienced by everyone sharing the island, presently. Revisiting the political past of her island nation is not as enjoyable as recalling her childhood memories for Swarna. Her brows furrow and her mood swiftly changes.

Post-independent Ceylon had many factors that pushed people apart. In 1956, language, a prime connector of social groups, was made into a divider almost overnight with the Sinhala Only Act. Alternatively known as the Official Language Act, it was a landmark piece of legislation that made Sinhala the sole official language of the island, replacing English, which had been the administrative language during British colonial rule. The Act led to grievances among the Tamil-speaking community, as they felt marginalized and disadvantaged due to the dominance of Sinhala in official matters.

Similarly, religion became increasingly associated with separate ethnolinguistic groups. Though Swarna’s family and Dharmalingam had managed to transcend these differences, the country plunged into a mire of heightened ethno-religious and linguistic nationalisms. Differences became insurmountable divisions. Social connectors weakened as dividers were inflamed through an array of political decisions and cultural movements.

“The world has changed. I can’t remember the last time I was at a cinema. I was horrified to find out that Rio was torched in the ’83 riots.” Swarna’s visible discomfort signals the end of a conversation, as well as the end of an era.

Re-discovering Rio

Today, Rio Cinema huddles amidst the bustling Slave Island quarter of Colombo. The area is now officially known as Kompannavidiya, but the name Slave Island, which reflects the area’s colonial legacy, is still used by many who inhabit the neighborhood. According to popular belief, there was a slave uprising in the 17th century, which resulted in them being confined to an area that subsequently became known as Slave Island.

However, according to researchers, the area’s name most likely originated from the fact that slaves working for the VOC had resided there at least since the early 1700s. Thus the area is a historian’s paradise, brimming with stories old and new, with and several visual layers easily detectable for anyone with an eye for detail: There are the bo trees, temples and kovils, serene and detached from the present chaos.

The run-down shop houses and derelict residential buildings, still pull off star presence without a lick of paint in years. Colonial structures, offices and warehouses add another distinctive layer. The old and new melt into each other in Slave Island, creating a heady mix that can easily throw you off your trail and pull you into colorful, competing anecdotes. The bright murals from the 2022 protests and the rising skyscrapers ambushing the neighborhood beckon with their stories.

But for now, let’s stay with the Rio.

When the cinema opened in February 1965, a journalist from the Ceylon Daily News raved: “As for being an average theater, the Rio is not…The seats are unobstructed, large and comfortable, upholstered in foam rubber and creamy-beige rexine, with satinwood arms…the vertically operated screen is a beauty.” Starting with the screening of the movie South Pacific, the Rio went on to create many memorable moments for its audiences, regaling them with classics such as Sound of Music and West Side Story on a 70mm screen.

The cinema is currently owned by Mr Ratnaraja Navaratnam. “It was my grandfather Appapillai, who started Navah Cinema in 1951 and then Rio. The theater is still in the same family,” he reminisces. Memories are bittersweet for the Navaratnams; the glory days when Rio was a plush venue for the crème de la crème of Colombo came to an end by the late 70s.

The National Film Corporation, established in 1972 with the aim of promoting ‘truly local cinema’, took over film distribution. International studios such as 20th Century Fox started boycotting the country. Navaratnam’s business started faltering. The deepest blow, however, came in the ugly form of Black July in 1983, the racial riots that sparked a long-drawn civil war, during which Rio, together with several other film halls owned by Tamils, were set ablaze by mobs of Sinhalese thugs as the Navaratnams were Tamil.

“My father was very hurt. More than the financial loss, he felt betrayed. He had done so much for the community and for this to happen in his own neighborhood was very saddening,” says Navaratnam. In the grim aftermath of the ’83 riots, the Navaratnams migrated to Australia, following the exodus of many Tamil families from all over the island. The silver screens of Colombo lost their glow.

However, the third son of the Navaratnam family held on to the charred building. “I never left Slave Island. I was born here. These days it is more harmonious. Slave Island has a vibrant population, with Sinhala, Muslim and Tamil people all living together. You find the mosques, temples, and churches all within each other’s reach. People coexist without any problem at all,” says Navaratnam.

Today, Rio Cinema wears a tragic air, with fading memories of glamor echoing in the empty hall. The dark corridors remind one of the murky skies filled with smoke; remnants of the fires lit during the riots. The cinema still makes it to Colombo’s social calendar once in a way, when a pop-up exhibition, a musical gig or an art festival seeking a venue off the beaten track takes place, and for a fleeting moment, Rio breathes.

Cinema in Colonial Ceylon: Pioneers

Today, many are unaware that cinema in Ceylon drew in the strengths of all its communities as well as its neighbors in its early days. It is a story of how new technology created space for harmony leading to immense creativity and beauty, and how nationalist politics eventually spelt doom for a thriving industry.

The most overlooked yet indomitable pioneer of the industry comes from the Bohra community. The Bohras are a small but affluent denomination within Sri Lanka’s Muslim community; one of many such smaller communities that blended into the social fabric of Ceylon, while maintaining their own distinctive identity. We have forgotten and lost a lot to history, but by what little is documented we know that T.A.J. Noorbhai was a force to reckon with.

He was referred to as a ‘general merchant’ in official colonial documentation. Noorbhai seemed to have made his wealth through his other business ventures, by the time he got feverishly invested in show-biz. He was a man of importance in the Colombo business community, dominated mostly by merchant families with Indian origins at the turn of the 20th century. For instance, he was called upon to deliver a vote of thanks at the opening ceremony of the Chalmers Warehouses in Pettah, declared open by Governor Robert Chalmers in 1915. Noorbhai was one of the first to set up a cinema hall and go into local film production.

Some accounts indicate that Noorbhai set up a cinema named London Bioscope, even before he moved to Southern Road in Maradana, transforming a former theater hall named Criterion to Olympia Cinema which opened on July 5, 1918. According to advertisements placed in Daily News, it was declared open by the Acting Governor at the time. The Eastern Theatre Company, which Noorbhai established, is one of the earliest film production companies of Ceylon.

The company imported and screened silent films to local audiences. Eventually, Noorbhai built a new cinema in Wellawatta. In 1923, Noorbhai was embroiled in a court case, against a so-called American filmmaker, Captain Salisbury, alias Duke Zellers. In his enthusiasm for film production, Noorbhai was swindled out of a large sum of money and film equipment he had invested in. Although the court ruled in favor of Noorbhai, the funds and camera equipment stolen were never recovered.

One might think this bitter experience may throw Noorbhai off film production forever. But we find him two years later, producing the first ever Ceylonese feature film, Rajakeeya Wickramaya (The Royal Adventure, also known as Shanta, 1925). When looking back on film history, the island mostly talks about the talkies, beginning with Kadadwunu Poronduwa (The Broken Promise, 1947), and Noorbhai’s attempts seem to get lost.

In a twist of fate, The Royal Adventure, though completed successfully and screened in Singapore and India, never made it to the island’s silver screens. On its way to Ceylon on a ship, the reels were destroyed in a fire. Some say that it was deliberately set on fire, by those who resented the success of Noorbhai. It is difficult to trace a verified sequence due to disparities in different sources, but what is clear is that Noorbhai shaped the early film industry, by setting up theater halls, filming studios, importing film equipment and investing in both film production and distribution.

There are other stories that may never be fully recovered. For instance, who was the beautiful Burgher actress cast as the heroine of the show? Some sources mention her name as Sybil Feam, others Sybil Pete. We will never really know who this mysterious first-ever Sri Lankan actress of the silver screen was. But what we do gather from all the silenced, erased and forgotten stories is the unmistakable narrative of how Bohras and Burghers, Sinhalese and Tamils, Ceylonese and Indians shaped the early days of cinema in Sri Lanka.

Newcomers from Jaffna

As the magic of cinema grew by the second decade of the 20th century, generating lucrative profits, film production and distribution became exclusively the domain of the rich. Those who entered it earlier tended to monopolize the industry. In a colonial world where hierarchy was the order of the day, the rich were the colonial powers themselves. Local entrepreneurs, like Noorbhai, though affluent by local standards, still had to hustle with foreign distribution companies and compete with bigger Indian film Moghuls like J.F. Madan with his film circuit flung across the empire from India to Indonesia. Setting up locally owned production and distribution companies required people cut out for the big game.

It was into this arena full of sharks that two local boys from Jaffna entered and made their name. Chittampalam Abraham Gardiner and Alfred Leo Savarimuttu Tambiah were both born in Jaffna and came from the educated Tamil upper class. They were both in their twenties when they changed the scene for Sri Lankan cinema. In 1928, Gardiner and Tambiah formed Ceylon Theatres, a turning point in the film industry in Ceylon. Today, Ceylon Theatres or CT Holdings is one of the largest conglomerates in the island, managing many cinemas, including Majestic City Cineplex, banks and several other subsidiary ventures.

Ceylon Theaters played a critical role in establishing local film production and distribution, directly financing many early Ceylonese films such as Asokamala, which was the second talkie to be released after Kadawunu Poronduwa. Gardiner went on to support Lester James Peiris’ Rekhava, considered the first realistic Sinhala film that broke the mold of commercial cinema, paving the way for films to become not just mass entertainment aimed at profit-making but a form of art. Language and ethnicity did not limit the worldview of the likes of Gardiner and Tambiah. For them, contributing to a thriving local film industry, strong enough to compete with the regional powerhouses of Bollywood and Kollywood, was the aim.

Knighted by the Pope later in life, Gardiner was universally acknowledged as the father of the Sri Lankan film industry. When he passed away in the 1960s, all cinema halls across the country closed down in mourning, and Parson’s Road where Ceylon Theatre’s first cinema Regal was established, was renamed Sir Chittampalam A. Gardiner Mawatha in his memory. He was luckier than Noorbhai in that regard, whose pioneering work is barely acknowledged.

(To be continued next week)

Features

Recruiting academics to state universities – beset by archaic selection processes?

Time has, by and large, stood still in the business of academic staff recruitment to state universities. Qualifications have proliferated and evolved to be more interdisciplinary, but our selection processes and evaluation criteria are unchanged since at least the late 1990s. But before I delve into the problems, I will describe the existing processes and schemes of recruitment. The discussion is limited to UGC-governed state universities (and does not include recruitment to medical and engineering sectors) though the problems may be relevant to other higher education institutions (HEIs).

How recruitment happens currently in SL state universities

Academic ranks in Sri Lankan state universities can be divided into three tiers (subdivisions are not discussed).

* Lecturer (Probationary)

– recruited with a four-year undergraduate degree. A tiny step higher is the Lecturer (Unconfirmed), recruited with a postgraduate degree but no teaching experience.

* A Senior Lecturer can be recruited with certain postgraduate qualifications and some number of years of teaching and research.

* Above this is the professor (of four types), which can be left out of this discussion since only one of those (Chair Professor) is by application.

State universities cannot hire permanent academic staff as and when they wish. Prior to advertising a vacancy, approval to recruit is obtained through a mind-numbing and time-consuming process (months!) ending at the Department of Management Services. The call for applications must list all ranks up to Senior Lecturer. All eligible candidates for Probationary to Senior Lecturer are interviewed, e.g., if a Department wants someone with a doctoral degree, they must still advertise for and interview candidates for all ranks, not only candidates with a doctoral degree. In the evaluation criteria, the first degree is more important than the doctoral degree (more on this strange phenomenon later). All of this is only possible when universities are not under a ‘hiring freeze’, which governments declare regularly and generally lasts several years.

Problem type 1

– Archaic processes and evaluation criteria

Twenty-five years ago, as a probationary lecturer with a first degree, I was a typical hire. We would be recruited, work some years and obtain postgraduate degrees (ideally using the privilege of paid study leave to attend a reputed university in the first world). State universities are primarily undergraduate teaching spaces, and when doctoral degrees were scarce, hiring probationary lecturers may have been a practical solution. The path to a higher degree was through the academic job. Now, due to availability of candidates with postgraduate qualifications and the problems of retaining academics who find foreign postgraduate opportunities, preference for candidates applying with a postgraduate qualification is growing. The evaluation scheme, however, prioritises the first degree over the candidate’s postgraduate education. Were I to apply to a Faculty of Education, despite a PhD on language teaching and research in education, I may not even be interviewed since my undergraduate degree is not in education. The ‘first degree first’ phenomenon shows that universities essentially ignore the intellectual development of a person beyond their early twenties. It also ignores the breadth of disciplines and their overlap with other fields.

This can be helped (not solved) by a simple fix, which can also reduce brain drain: give precedence to the doctoral degree in the required field, regardless of the candidate’s first degree, effected by a UGC circular. The suggestion is not fool-proof. It is a first step, and offered with the understanding that any selection process, however well the evaluation criteria are articulated, will be beset by multiple issues, including that of bias. Like other Sri Lankan institutions, universities, too, have tribal tendencies, surfacing in the form of a preference for one’s own alumni. Nevertheless, there are other problems that are, arguably, more pressing as I discuss next. In relation to the evaluation criteria, a problem is the narrow interpretation of any regulation, e.g., deciding the degree’s suitability based on the title rather than considering courses in the transcript. Despite rhetoric promoting internationalising and inter-disciplinarity, decision-making administrative and academic bodies have very literal expectations of candidates’ qualifications, e.g., a candidate with knowledge of digital literacy should show this through the title of the degree!

Problem type 2 – The mess of badly regulated higher education

A direct consequence of the contemporary expansion of higher education is a large number of applicants with myriad qualifications. The diversity of degree programmes cited makes the responsibility of selecting a suitable candidate for the job a challenging but very important one. After all, the job is for life – it is very difficult to fire a permanent employer in the state sector.

Widely varying undergraduate degree programmes.

At present, Sri Lankan undergraduates bring qualifications (at times more than one) from multiple types of higher education institutions: a degree from a UGC-affiliated state university, a state university external to the UGC, a state institution that is not a university, a foreign university, or a private HEI aka ‘private university’. It could be a degree received by attending on-site, in Sri Lanka or abroad. It could be from a private HEI’s affiliated foreign university or an external degree from a state university or an online only degree from a private HEI that is ‘UGC-approved’ or ‘Ministry of Education approved’, i.e., never studied in a university setting. Needless to say, the diversity (and their differences in quality) are dizzying. Unfortunately, under the evaluation scheme all degrees ‘recognised’ by the UGC are assigned the same marks. The same goes for the candidates’ merits or distinctions, first classes, etc., regardless of how difficult or easy the degree programme may be and even when capabilities, exposure, input, etc are obviously different.

Similar issues are faced when we consider postgraduate qualifications, though to a lesser degree. In my discipline(s), at least, a postgraduate degree obtained on-site from a first-world university is preferable to one from a local university (which usually have weekend or evening classes similar to part-time study) or online from a foreign university. Elitist this may be, but even the best local postgraduate degrees cannot provide the experience and intellectual growth gained by being in a university that gives you access to six million books and teaching and supervision by internationally-recognised scholars. Unfortunately, in the evaluation schemes for recruitment, the worst postgraduate qualification you know of will receive the same marks as one from NUS, Harvard or Leiden.

The problem is clear but what about a solution?

Recruitment to state universities needs to change to meet contemporary needs. We need evaluation criteria that allows us to get rid of the dross as well as a more sophisticated institutional understanding of using them. Recruitment is key if we want our institutions (and our country) to progress. I reiterate here the recommendations proposed in ‘Considerations for Higher Education Reform’ circulated previously by Kuppi Collective:

* Change bond regulations to be more just, in order to retain better qualified academics.

* Update the schemes of recruitment to reflect present-day realities of inter-disciplinary and multi-disciplinary training in order to recruit suitably qualified candidates.

* Ensure recruitment processes are made transparent by university administrations.

Kaushalya Perera is a senior lecturer at the University of Colombo.

(Kuppi is a politics and pedagogy happening on the margins of the lecture hall that parodies, subverts, and simultaneously reaffirms social hierarchies.)

Features

Talento … oozing with talent

This week, too, the spotlight is on an outfit that has gained popularity, mainly through social media.

This week, too, the spotlight is on an outfit that has gained popularity, mainly through social media.

Last week we had MISTER Band in our scene, and on 10th February, Yellow Beatz – both social media favourites.

Talento is a seven-piece band that plays all types of music, from the ‘60s to the modern tracks of today.

The band has reached many heights, since its inception in 2012, and has gained recognition as a leading wedding and dance band in the scene here.

The members that makeup the outfit have a solid musical background, which comes through years of hard work and dedication

Their portfolio of music contains a mix of both western and eastern songs and are carefully selected, they say, to match the requirements of the intended audience, occasion, or event.

Although the baila is a specialty, which is inherent to this group, that originates from Moratuwa, their repertoire is made up of a vast collection of love, classic, oldies and modern-day hits.

The musicians, who make up Talento, are:

Prabuddha Geetharuchi:

(Vocalist/ Frontman). He is an avid music enthusiast and was mentored by a lot of famous musicians, and trainers, since he was a child. Growing up with them influenced him to take on western songs, as well as other music styles. A Peterite, he is the main man behind the band Talento and is a versatile singer/entertainer who never fails to get the crowd going.

Geilee Fonseka (Vocals):

A dynamic and charismatic vocalist whose vibrant stage presence, and powerful voice, bring a fresh spark to every performance. Young, energetic, and musically refined, she is an artiste who effortlessly blends passion with precision – captivating audiences from the very first note. Blessed with an immense vocal range, Geilee is a truly versatile singer, confidently delivering Western and Eastern music across multiple languages and genres.

Chandana Perera (Drummer):

His expertise and exceptional skills have earned him recognition as one of the finest acoustic drummers in Sri Lanka. With over 40 tours under his belt, Chandana has demonstrated his dedication and passion for music, embodying the essential role of a drummer as the heartbeat of any band.

Harsha Soysa:

(Bassist/Vocalist). He a chorister of the western choir of St. Sebastian’s College, Moratuwa, who began his musical education under famous voice trainers, as well as bass guitar trainers in Sri Lanka. He has also performed at events overseas. He acts as the second singer of the band

Udara Jayakody:

(Keyboardist). He is also a qualified pianist, adding technical flavour to Talento’s music. His singing and harmonising skills are an extra asset to the band. From his childhood he has been a part of a number of orchestras as a pianist. He has also previously performed with several famous western bands.

Aruna Madushanka:

(Saxophonist). His proficiciency in playing various instruments, including the saxophone, soprano saxophone, and western flute, showcases his versatility as a musician, and his musical repertoire is further enhanced by his remarkable singing ability.

Prashan Pramuditha:

(Lead guitar). He has the ability to play different styles, both oriental and western music, and he also creates unique tones and patterns with the guitar..

Features

Special milestone for JJ Twins

The JJ Twins, the Sri Lankan musical duo, performing in the Maldives, and known for blending R&B, Hip Hop, and Sri Lankan rhythms, thereby creating a unique sound, have come out with a brand-new single ‘Me Mawathe.’

In fact, it’s a very special milestone for the twin brothers, Julian and Jason Prins, as ‘Me Mawathe’ is their first ever Sinhala song!

‘Me Mawathe’ showcases a fresh new sound, while staying true to the signature harmony and emotion that their fans love.

This heartfelt track captures the beauty of love, journey, and connection, brought to life through powerful vocals and captivating melodies.

It marks an exciting new chapter for the JJ Twins as they expand their musical journey and connect with audiences in a whole new way.

Their recent album, ‘CONCLUDED,’ explores themes of love, heartbreak, and healing, and include hits like ‘Can’t Get You Off My Mind’ and ‘You Left Me Here to Die’ which showcase their emotional intensity.

Readers could stay connected and follow JJ Twins on social media for exclusive updates, behind-the-scenes moments, and upcoming releases:

Instagram: http://instagram.com/jjtwinsofficial

TikTok: http://tiktok.com/@jjtwinsmusic

Facebook: http://facebook.com/jjtwinssingers

YouTube: http://youtube.com/jjtwins

-

Opinion5 days ago

Opinion5 days agoJamming and re-setting the world: What is the role of Donald Trump?

-

Features5 days ago

Features5 days agoAn innocent bystander or a passive onlooker?

-

Features6 days ago

Features6 days agoRatmalana Airport: The Truth, The Whole Truth, And Nothing But The Truth

-

Features6 days ago

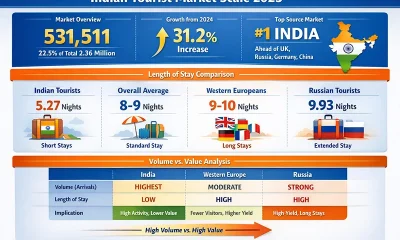

Features6 days agoBuilding on Sand: The Indian market trap

-

Business7 days ago

Business7 days agoDialog partners with Xiaomi to introduce Redmi Note 15 5G Series in Sri Lanka

-

Opinion6 days ago

Opinion6 days agoFuture must be won

-

Business6 days ago

Business6 days agoIRCSL transforms Sri Lanka’s insurance industry with first-ever Centralized Insurance Data Repository

-

Opinion1 day ago

Opinion1 day agoSri Lanka – world’s worst facilities for cricket fans