Life style

King of Noodles

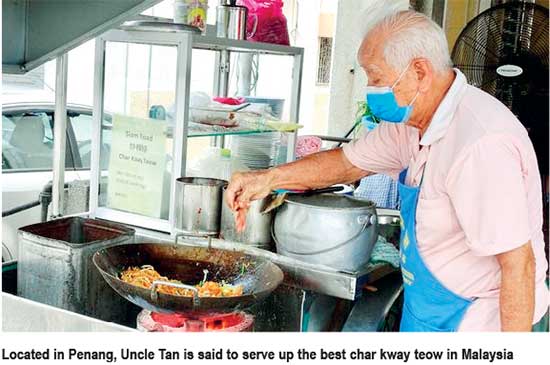

Food-loving Malaysians have been known to debate the best local food spots for hours. Tan Chooi Hong, hunched over a blazing hot wok, hadn’t broken a sweat. Flames from the charcoal sparked and danced up the side of the wok, crackling as he added the ingredients one by one, just as his father taught him almost 60 years ago. Char kway teow, Malaysia’s most famous street food, is a simple rice noodle dish made with soy sauce, eggs, cockles, bean sprouts, Chinese sausage and a couple of shrimp. It’s common throughout the country – devoured at roadside stalls or feasted on at hawker centres – but there is only one “king” of char kway teow, and he’s in Penang. Uncle Tan, as he’s known, is a sturdy 79-year-old with a shock of white hair and an all-knowing glimmer in his eye. He’s been cooking this single dish from a wok-cart attached to a bicycle and pushed into place on the side of Siam Road in central George Town for decades. “I don’t remember how old I was when I started. But char kway teow is all I know,” said Uncle Tan.

Uncle Tan’s unlikely fame began in 2012 when he was interviewed by a local who put the story on Facebook. His decades of cooking experience, combined with layered flavours of smoky-unctuous noodles perfectly balanced with the salty-sweet Chinese sausage, quickly got the younger generation of foodies salivating. Nothing is better than a simple noodle dish with an interesting backstory, and young Penangites ate it up. The article went viral and people began flying to the island just to taste his dish.

In 2015, celebrity chef Martin Yan, known for his Yan Can Cook TV show, visited the stall for his TV show Taste of Malaysia. If that fame didn’t cement Uncle Tan’s title as king, placing 14th (out of 50) at the World Street Food Congress in 2017 certainly did. Today, his roadside wok-cart is a fixture in the food scene and he’s widely revered as serving up the most delicious, flavoursome char kway teow in Malaysia, churning out hundreds of plates a day with people waiting in line for hours.

In 2015, celebrity chef Martin Yan, known for his Yan Can Cook TV show, visited the stall for his TV show Taste of Malaysia. If that fame didn’t cement Uncle Tan’s title as king, placing 14th (out of 50) at the World Street Food Congress in 2017 certainly did. Today, his roadside wok-cart is a fixture in the food scene and he’s widely revered as serving up the most delicious, flavoursome char kway teow in Malaysia, churning out hundreds of plates a day with people waiting in line for hours.

Uncle Tan is unfazed by his fame and prefers to keep a low profile. Humble and shy, he can’t understand what all the fuss is about and doesn’t think his version is any better than anoyone else’s.

“My dad didn’t go to school to learn any skills. It wasn’t an option. He had to work for his father, so he worked by his side cooking char kway teow every day,” his daughter, Tan Evelyn, told . “And he’s never stopped.”

The ingredients of char kway teow are so simple that it takes a lot of skill to get it right. The main ingredient is flat rice noodles. No self-respecting char kway teow stall would use dried noodles, so Uncle Tan gets bags of the fresh, chewy goodness delivered by scooter regularly.

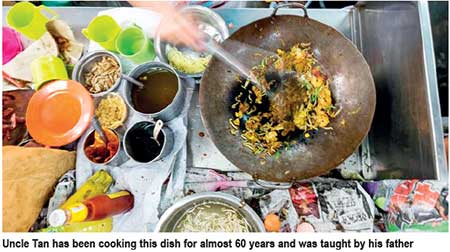

I watched as he skillfully added one ingredient at a time, just by feel and sight. He threw a large handful of slippery noodles in the blisteringly hot wok and used a wide metal spatula to spin them around in the garlic and lard waiting for them. After pushing the noodles up the side of the pan, he expertly cracked an egg into the middle, breaking it with the spatula to let the yolk ooze into the noodles.

A few soy sauce dashes, a spoonful of chilli sauce and a little water created a silky sauce that the noodles absorbed. Then Uncle Tan tossed in a couple of shrimp and a few slices of sweet lap cheong, or Chinese sausage. Finally, a smattering of cockles got a spin in the wok. He topped it all with a handful of crunchy bean sprouts, chives and small homemade croutons made of crispy pork fat.

He eyed the steaming noodles for the perfect consistency and then scooped them onto a melamine plate and started all over again. The whole process was lightning fast – less than two minutes – and Uncle Tan made it look effortless.

While many stalls use gas, Uncle Tan cooks on charcoal, frying one order at a time for maximum flavour and wok hei, which translates to “breath of the wok”. Wok hei is the smoky depth of flavour that charcoal adds to the dish and is expertly created by cooking the right portion over the right temperature. It’s something that gas heat cannot achieve.

Some people say that charcoal is the secret to Uncle Tan’s success, but, “they like my father’s char kway teow better than others because he’s perfected it over 60 years,” said Evelyn. “Other stalls use charcoal and the same ingredients, but no-one has his skill. Not even my brother Kean Huat who learned from him.”

Others try to attribute Uncle’s success to a secret sauce. “I promise. There is no secret sauce; it’s his wok skill,” said Evelyn. “I also cannot fry as my brother or dad. My brother has been working for years learning from my dad, and his skills are still improving. It takes a lifetime. Just ask my dad.”

“If I give you the same ingredients, you cannot make the same taste as me,” agreed Uncle Tan.

Even though char kway teow has become synonymous with Penang street food, its origins lie in China. In the 19th Century, the Chinese diaspora brought over Teochew and Hokkien people from Guangdong and Fujian provinces on China’s south-eastern coast. During that same time, Penang grew under British rule and it became a bustling entrepot providing greater employment opportunites. The Hokkien people came to work in the rubber plantations and as traders and merchants, while the Teochew found jobs in the tin mines and as fisherman. With them came some of their kitchen staples like soy sauce, bean curd and noodles called kway teow.

In Hokkien, the word char means “stir-fried”, and kway teow means “rice cake strips”, referring to the noodles. What had begun in China’s south-eastern provinces as a simple noodle dish with pork, fish sauce and soy sauce was transformed into a seafood delight once it hit the island’s shores. Initially, it was sold at night by fisherman and cockle gatherers trying to make an extra buck. Instead of the traditional ingredients, they used what was plentiful to create a revised version of the dish. It was a poor man’s food and the other Chinese immigrants devoured it as something fast, cheap and tasty to sustain them for hours under the hot sun. The dish became a labourer’s staple.

“When the waves of Teochew and Hokkien immigrants came from China, they came alone, leaving their wives and families behind. Since there was no-one to cook for them, they survived on cheap street food,” said Nazlina Hussin, a Penangite culinary specialist and author. “From wok to plate, char kway teow takes no time. These men could stop for lunch, eat and be back to work within a few minutes.”

To this day, most of the Chinese in Penang are of Hokkien and Teochew descent. It’s the only place in Malaysia where Hokkien is commonly spoken, which is why char kway teow has remained so closely linked to Penang. And although you can find the dish outside of Penang, locals say it’s not as good unless a Hokkien or Teochew makes it. That’s why people fly here from Kuala Lumpur and Singapore and wait in line for hours, in the hot sun, to try Uncle Tan’s char kway teow.

It’s that good.

Plus, he’s one of the oldest char kway teow legends in Malaysia. There is a reverence in that. “Most customers come here for my dad. People say he’s a char kway teow idol. So, if he’s not cooking, they keep on driving,” said Evelyn.

In 2018, for the first time in nearly 60 years, Uncle Tan took a break. On doctor’s orders after cataract surgery, he closed his shop for six months, and his devotees, like those of any idol or guru, went berserk. The whole island almost had a breakdown, with stories in local media lamenting his sudden overnight retirement. “Today we’ve had to endure the greatest loss of mankind,” wrote culinary website Penang Foodie. “Siam Road Char Koay Teow is believed to be closed down for go

Uncle Tan’s son took over for a brief moment and locals weren’t kind to him; Penangites are loyal foodies and they wanted the master’s char kway teow. After six months of ever-more grandiose gossip, “We had to find a place; we couldn’t let the people down,” declared Evelyn. Instead of going back to his original roadside spot, they decided to find a premises on the same street. Today Uncle Tan still cooks from a bike pushcart with a wok attached; it’s just parked in front of his shop.

He’s widely revered as serving up the most delicious, flavoursome char kway teow in Malaysia

“Now, my son and I can take turns cooking. When I get tired, I can sit down and watch Kean Huat try to perfect my dish,” he said with a wink. “It isn’t easy. But he’s a third-generation char kway teow cook, and even though he didn’t start as young as I did, he’ll be able to perfect his skills one day too.”

Uncle Tan’s char kway teow is not only Penang’s history on a plate; it’s his family’s history as well. Hopefully, Kean Huat will live up to his father’s reputation and teach future generations how to follow in the king’s footsteps.

But until then, “I have no plans to retire. As long as I can still stand and cook over the wok, I’ll be here on Jalan Siam,” laughed Uncle Tan.–BBC

Life style

From Vanishing Sea Snakes to DNA in a Bottle

Dr. Ruchira Somaweera on Rethinking Conservation

What happens when one of the world’s richest marine biodiversity hotspots collapses almost overnight — and no one knows why?

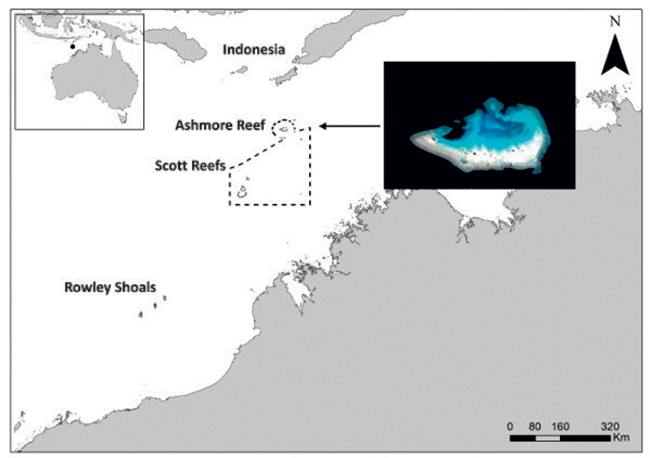

That was the question facing Australian authorities in the early 2000s when Ashmore Reef, a remote marine reserve in the Timor Sea, suddenly lost what once made it globally unique: its extraordinary diversity and abundance of sea snakes.

“At one point, this place had more species of sea snakes and more individuals than anywhere else on Earth,” recalled Dr. Ruchira Somaweera, one of the world’s leading reptile biologists. “Then, within a few years, everything collapsed.”

Speaking at a packed Wildlife and Nature Protection Society (WNPS) Monthly Lecture, sponsored by Nations Trust Bank and held at the BMICH, Dr. Somaweera described how the mysterious disappearance triggered a major federal investigation.

“At the time, I was a federal government scientist,” he said. “We were sent to find out what went wrong — but it wasn’t obvious at all.”

Ashmore Reef, a protected area managed by Parks Australia, was still teeming with turtles, sharks and pelagic birds. Yet the sea snakes — once recorded at rates of up to 60 individuals per hour — had virtually vanished.

The breakthrough came not from the water, but from policy.

For decades, traditional Indonesian fishers from Roti Island had been permitted to harvest sharks at Ashmore under a bilateral agreement. When Australia banned shark fishing around 2000, shark numbers rebounded rapidly.

“And sharks are the main predators of sea snakes,” Dr. Somaweera explained. “What we realised is that what we thought was ‘normal’ may actually have been an imbalance.”

In other words, sea snakes had flourished during an unusual window when their top predators were suppressed. Once sharks returned, the ecosystem corrected itself — with dramatic consequences.

“It was a powerful lesson,” he said. “Sometimes collapse isn’t caused by pollution or climate change, but by ecosystems returning to balance.”

The mystery didn’t end there. Some sea snake species once known only from Ashmore were now feared extinct. But instead of accepting that conclusion, Dr. Somaweera and colleagues took a different approach — one that combined science with local knowledge.

“Scientists often fail by not talking to the people who live with these animals,” he said. “Fishermen have decades of experience. That knowledge matters.”

Using museum records, fisher interviews and species distribution modelling, the team predicted where these snakes might still exist. The models suggested vast new areas — some the size of Sri Lanka — had never been properly surveyed.

When researchers finally reached these sites, often involving helicopters, research vessels and enormous logistical costs, they made a startling discovery.

“We found populations of species we thought were gone,” he said. “They were there all along. We were just looking in the wrong place.”

Even more surprising was where they were found — far deeper than expected.

Traditional sea snake surveys rely on night-time spotlighting, assuming snakes surface to breathe and rest. But footage from deep-sea remotely operated vehicles (ROVs) revealed that many species live in the mesophotic zone, where light fades and surveys rarely reach.

“Some of these snakes are deep divers,” Dr. Somaweera said. “They don’t behave the way we assumed.”

That insight led to one of his most remarkable discoveries — coordinated, communal hunting in the Irabu sea krait off Indonesia.

“At 40 metres deep, on the slope of an extinct volcano, we found them hunting in groups,” he said. “They take turns flushing fish and feeding. That level of cooperation was never known in snakes.”

Beyond discovery, Dr. Somaweera’s work increasingly focuses on how conservation itself must evolve.

One of the most transformative tools, he said, is environmental DNA (eDNA) — the ability to detect species from genetic traces left in water, soil or even air.

“You no longer need to see the animal,” he explained. “A bottle of water can tell you what lives there.”

His team now uses eDNA to detect critically endangered snakes, turtles and sea snakes in some of Australia’s most remote regions. In one project, even children were able to collect samples.

“A 10-year-old can do it,” he said. “That’s how accessible this technology has become.”

The implications for countries like Sri Lanka are profound. From snakebite management to marine conservation, eDNA offers a low-impact, cost-effective way to monitor biodiversity — especially in hard-to-reach areas.

Dr. Somaweera ended his lecture with a message aimed squarely at young scientists.

“We already have a lot of data. What we lack is the next question,” he said. “So what? That’s the question that turns knowledge into action.”

After nearly two decades of research across continents, his message was clear: conservation cannot rely on assumptions, tradition or good intentions alone.

“It has to be evidence-based,” he said. “Because only action — informed by science — actually saves species.”

By Ifham Nizam ✍️

Life style

Driving the vision of Colombo Fashion Week

Fazeena Rajabdeen

Fazeena Rajabdeen stands at the forefront of Sri Lanka’s fashion evolution as the Executive Director of Colombo Fashion Week.

Fazeena Rajabdeen stands at the forefront of Sri Lanka’s fashion evolution as the Executive Director of Colombo Fashion Week.

With a visionary approach that bridges local talent with global opportunities, Fazeena has been instrumental in elevating Colombo Fashion Week into a sought-after platform for designers, buyers and industry innovators. In this interview, she shares insights on the growth of Sri Lanka’s fashion landscape, the challenges and triumphs of steering a major fashion event, and her aspirations for the future of the industry.

(Q) As Executive Director of Colombo Fashion Week, how do you define CFW’s role in shaping Sri Lanka’s fashion identity?

(A) CFW is fundamentally the backbone of Sri Lanka’s fashion industry. Over 23 years, we’ve built more than a platform, we’ve crafted an entire fashion ecosystem that didn’t exist before.

What I’m most proud of is that over 80% of the designers you see in Sri Lanka today have come through our development system. That’s not accidental, it’s the result of building infrastructure, including partnerships, brand development support, retail insights, and international networks. We’ve essentially created the conditions for a Sri Lankan fashion industry to emerge organically, rooted in our heritage but completely contemporary in its expression. This has resulted in the creation of few design education schools, fashion retailers, model academies.

CFW has given Sri Lankan fashion an identity that carries weight, one that speaks to craftsmanship, sustainability, and creative integrity. That’s the legacy we continue to build upon.

(Q) What has been your personal vision in steering Colombo Fashion Week over the years?

(A) My vision has always been about scale and sustainability, taking what was a seasonal event and building it into a year-round business ecosystem. My key focus was on developing the next generation through structured programs like emerging designers and CFW Accelerate, embedding responsibility into fashion through tools like the Responsible Meter, and expanding our reach with new editions and International partnerships.

We’ve moved from showcasing fashion to building the infrastructure that makes sustainable, commercially viable fashion careers possible in Sri Lanka. Another mission was to expand the platform so Sri Lankan designers aren’t just showing collections, they’re building brands that compete regionally, especially within South Asia.

(Q) Fashion Weeks globally are evolving. How has CFW adapted while staying true to its roots?

(A) The role of fashion platforms has evolved, as the development of fashion, the consumption of fashion and choices fashion consumers make has changed. At the core Fashion is an emotional choice hence engagement with fashion consumers remains high priority. CFW as a platform that leads the fashion industry, creates formats that effectively engage consumers with the fashion creators and with that open opportunities in Sri Lanka and internationally through BRICS, South Asia and Beyond. There are interesting new projects planned to push this forward.

(Q) How does CFW contribute to positioning Colombo as a regional fashion and lifestyle capital?

(A) CFW is known as a renowned South Asian Fashion Week and serves as a regional hub with its longstanding influence of 23 years in the region. That longevity alone has made us a reference point for South Asian fashion and we’ve become first-in-mind when people think of fashion here.

But it’s more than just presence. CFW has positioned the city with its synonymous brand name and interaction with influential people within the region as a lifestyle destination, not a peripheral market. That sustained visibility and the calibre of what we produce has put Colombo on the map as a regional capital where fashion, craft, and commerce intersect.

(Q) Sustainability and craftsmanship are growing conversations—How are those reflected in designer collections?

(A) Responsibility in fashion has been our cornerstone from the beginning. We’ve always championed Batik and traditional craft, and we’ve backed that with real resources through our craft funds.

What we’ve done differently is make sustainability measurable. The Responsible Meter we developed is a transparent scoring system that shows the environmental and social impact of each garment. Designers now build collections with accountability baked in from the start, not as an afterthought. This process is included in all emerging designer development processes.

(Q) Colombo Fashion Week has been a launch pad for many designers. What do you look for when curating talent?

(A) Above all—passion and drive. You can teach technique, refine a collection, connect someone to the right resources. But that hunger to build something, to push through the hard parts of turning creativity into a viable business That has to come from them.

We look for designers who understand that fashion is both art and commerce. They need a point of view, yes, but also the discipline to execute it consistently. The ones who succeed through CFW are the ones who see the platform as a starting point, not the finish line—they’re ready to put in the work to build a real brand, not just show a collection and continue with us in building that brand.

(Q) What role does CFW play in connecting Sri Lankan designers to global markets?

(A) CFW set out on a designer exchange programme through the BRICS International Fashion Federation, showcasing Sri Lankan talent at BRICS fashion weeks while welcoming international designers to Colombo. The platform positions Sri Lanka within the global fashion landscape while attracting international buyers and media. We have partnerships with the commonwealth countries and relevant fashion weeks. The interaction with global designers we invite during fashion week is primarily to focus on such interactions with Sri Lankan designers, opening doors for learnings and opportunities.

(Q) What can we expect from upcoming editions of CFW?

(A) Every edition has a unique focus to it and we work towards creating more expansion, more accessibility. We’re doubling down on our development programs, bringing in stronger international partnerships, deeper craft integration, and wider opportunities for designers at every stage.

We’re also looking at new formats and editions that create the Sri Lankan story in international markets.

We focus on being beyond a showcase; as the engine that drives Sri Lankan fashion forward regionally and globally. We’re building for scale and impact. The upcoming editions will reflect that ambition.

(Q) You have Co-founded the Ceylon Literary and Arts Festival, what inspired you to start and what was your original vision?

(A) It was a natural expansion, honestly. After years of building CFW and seeing the power of creative platforms, we realized there is space for the same thing for arts and literature, a space that celebrates Sri Lanka’s intellectual and cultural soft power.

The vision was simple: create a festival that puts Sri Lankan voices in conversation with regional and global thought leaders. Literature and the arts are incredible tools for cultural influence, and we weren’t leveraging that enough. Ceylon Literary and Arts Festival became that platform, a way to showcase our writers, artists, and thinkers while positioning Sri Lanka as a hub for meaningful cultural exchange.

It’s about soft power. Fashion opened doors, arts and literature deepened the conversation. Together, they tell a fuller story of who we are as a country.

(Q) What makes it unique in Sri Lanka’s cultural scene?

(A) It’s the ecosystem with its breadth and accessibility. We’ve built a festival that doesn’t silo creativity, it brings together literature, art, film, performing arts and music under one platform. That cross-pollination doesn’t really exist elsewhere in Sri Lanka at this scale.

What sets us apart is that we’ve made it deliberately accessible, students are free as our focus is the Youth. Projects and processes that empower the youth and foster creative talent from the grassroot.

(Q) What role does the festival play in promoting local writers, poets and literary talent?

(A) We platform both established names and emerging voices who haven’t had the visibility. The festival creates real dialogue and gives local talent stages they wouldn’t normally access.

We take the best of the world.

We’ve made it accessible, students get free entry, and we run a Children’s Festival for ages 5 to 11. It’s about building pathways early and giving Sri Lankan writers, poets, and creatives the exposure that launches careers.

Our winner of the first edition of the Future writers’ program, was recently awarded the acclaimed Gratiaen Award. We were happy we were able to mentor and pave the pathway for Savin and all future writers for the next generation.

(Q) What are the next dates to look out for?

(A) We have the HSBC Ceylon Literary and Arts Festival Edition 03 set to take place February 13th ,14th,15th 2026. This year’s Festival brings together creativity across all genres including the children’s festival, performing arts and Arts festival. We are proud to celebrate Sri Lankan and international Authors including the renowned author of the Bridgerton series Julia Quinn.

Following which the annual Summer edition of Colombo Fashion Week will take place in March 2026

This is for the start of 2026. looking forward to many exciting plans for the rest of the year.

Life style

The HALO Trust appoints Rishini Weeraratne as its Ambassador for Sri Lanka

The HALO Trust, the world’s largest humanitarian landmine clearance organization, has appointed Rishini Weeraratne as its Ambassador for Sri Lanka. In her new role, she will support HALO’s global mission by raising awareness of mine action, strengthening advocacy efforts, and championing initiatives to protect communities impacted by landmines and unexploded ordnance, particularly in Sri Lanka. She will also play a key role in HALO’s international engagement and communications initiatives.

HALO began working in Afghanistan in 1988. Today HALO operates in more than 30 countries and territories across Africa, Asia, Europe and Caucasus, Latin America, and the Middle East. Its teams work daily to clear landmines, deliver risk education and restore land for agriculture, homes and infrastructure. HALO gained international recognition after Diana, Princess of Wales, visited its work in Angola in 1997 which helped accelerate support for the Mine Ban Treaty. Sri Lanka is one of HALO’s longest standing programmes. HALO has been operational in the island since 2002 and has cleared more than 300,000 mines and over one million explosive remnants of war, enabling thousands of families to return home safely. HALO is the second largest employer in the Northern Province, and its workforce is 99 percent locally recruited. Women make up 42 percent of the demining teams, reflecting HALO’s commitment to local empowerment and employment in post conflict communities.

Rishini Weeraratne, Ambassador for Sri Lanka, The HALO Trust:

“It is a privilege to support The HALO Trust’s mission. Although Sri Lanka is my home country and close to my heart, I am also committed to advocating for HALO’s work around the world. Millions of people live with the daily risk of landmines and unexploded ordnance. By raising awareness and amplifying the voices of affected communities, I hope to contribute to a safer future for families everywhere.”

-

Editorial2 days ago

Editorial2 days agoIllusory rule of law

-

News3 days ago

News3 days agoUNDP’s assessment confirms widespread economic fallout from Cyclone Ditwah

-

Business5 days ago

Business5 days agoKoaloo.Fi and Stredge forge strategic partnership to offer businesses sustainable supply chain solutions

-

Editorial3 days ago

Editorial3 days agoCrime and cops

-

Features2 days ago

Features2 days agoDaydreams on a winter’s day

-

Editorial4 days ago

Editorial4 days agoThe Chakka Clash

-

Features2 days ago

Features2 days agoSurprise move of both the Minister and myself from Agriculture to Education

-

Features2 days ago

Features2 days agoThe Story of Furniture in Sri Lanka