Features

Inside the deadly instant loan app scam that blackmails with nudes

A blackmail scam is using instant loan apps to entrap and humiliate people across India and other countries in Asia, Africa, and Latin America. At least 60 Indians have killed themselves after being abused and threatened. A BBC undercover investigation has exposed those profiting from this deadly scam in India and China.

Astha Sinhaa woke up to her aunt’s panicked voice on the phone. “Don’t let your mother leave the house.” Half-asleep, the 17-year-old was terrified to find her mum Bhoomi Sinhaa in the next room, sobbing and frantic.

Here was her funny and fearless mother, a respected Mumbai-based property lawyer, a widow raising her daughter alone, reduced to a frenzied mess. “She was breaking apart,” Astha says. A panicked Bhoomi started telling her where all the important documents and contacts were, and seemed desperate to get out of the door. Astha knew she had to stop her. “Don’t let her out of your sight,” her aunt had told her. “Because she will end her life.”

Astha knew her mother had been getting some weird calls and that she owed somebody money, but she had no idea that Bhoomi was reeling from months of harassment and psychological torture. She had fallen victim to a global scam with tentacles in at least 14 countries that uses shame and blackmail to make a profit – destroying lives in the process.

The business model is brutal but simple.

There are many apps that promise hassle-free loans in minutes. Not all of them are predatory. But many – once downloaded – harvest your contacts, photos and ID cards, and use that information later to extort you.

When customers don’t repay on time – and sometimes even when they do – they share this information with a call centre where young agents of the gig economy, armed with laptops and phones are trained to harass and humiliate people into repayment.

At the end of 2021, Bhoomi had borrowed about 47,000 rupees ($565; £463) from several loan apps while she waited for some work expenses to come through. The money arrived almost immediately but with a big chunk deducted in charges. Seven days later she was due to repay but her expenses still hadn’t been paid, so she borrowed from another app and then another. The debt and interest spiralled until she owed about two million rupees ($24,000; £19,655).

Soon the recovery agents started calling. They quickly turned nasty, slamming Bhoomi with insults and abuse. Even when she had paid, they claimed she was lying. They called up to 200 times a day. They knew where she lived, they said, and sent her pictures of a dead body as a warning.

As the abuse escalated they threatened to message all of the 486 contacts in her phone telling them she was a thief and a whore. When they threatened to tarnish her daughter’s reputation too, Bhoomi could no longer sleep.

She borrowed from friends, family and more and more apps – 69 in total. At night, she prayed the morning would never come. But without fail at 07:00, her phone would start pinging and buzzing incessantly.

Eventually, Bhoomi had managed to pay back all of the money, but one app in particular – Asan Loan – wouldn’t stop calling. Exhausted, she couldn’t concentrate at work and started having panic attacks.

One day a colleague called her over to his desk and showed her something on his phone – a naked, pornographic picture of her. The photo had been crudely photoshopped, Bhoomi’s head stuck on someone else’s body, but it filled her with disgust and shame. She collapsed by her colleague’s desk. It had been sent by Asan Loan to every contact in her phone book. That was when Bhoomi thought of killing herself.

We’ve seen evidence of scams like this run by various companies all over the world. But in India alone, the BBC has found at least 60 people have killed themselves after being harassed by loan apps. Most were in their 20s and 30s – a fireman, an award-winning musician, a young mum and dad leaving behind their three- and five-year-old daughters, a grandfather and grandson who got involved in loan apps together. Four were just teenagers.

Most victims are too ashamed to speak about the scam, and the perpetrators have remained, for the most part, anonymous and invisible. After looking for an insider for months, the BBC managed to track down a young man who had worked as a debt recovery agent for call centres working for multiple loan apps.

Rohan – not his real name – told us he had been troubled by the abuse he had witnessed. Many customers cried, some threatened to kill themselves, he said. “It would haunt me all night.” He agreed to help the BBC expose the scam.

He applied for a job in two different call centres – Majesty Legal Services and Callflex Corporation – and spent weeks filming undercover. His videos captured young agents harassing clients. “Behave or I will smash you,” one woman says, swearing. She accuses the customer of incest and, when he hangs up, she starts laughing. Another suggests the client should prostitute his mother to repay the loan.

Rohan recorded over 100 incidents of harassment and abuse, capturing this systematic extortion on camera for the first time. The worst abuse he witnessed took place at Callflex Corporation, just outside Delhi. Here, agents routinely used obscene language to humiliate and threaten customers. These were not rogue agents going off-script – they were supervised and directed by managers at the call centre, including one called Vishal Chaurasia.

Rohan gained Chaurasia’s trust, and together with a journalist posing as an investor, arranged a meeting at which they asked him to explain exactly how the scam works.

When a customer takes out a loan, he explained, they give the app access to the contacts on their phone. Callflex Corporation is hired to recover the money – and if the customer misses a payment the company starts hassling them, and then their contacts. His staff can say anything, Chaurasia told them, as long as they get a repayment.

“The customer then pays because of the shame,” he said. “You’ll find at least one person in his contact list who can destroy his life.”

We approached Chaurasia directly but he did not want to comment. Callflex Corporation did not respond to our efforts to contact them.

One of the many lives destroyed was Kirni Mounika’s. The 24-year-old civil servant was the brains of her family, the only student at her school to get a government job, a doting sister to her three brothers. Her father, a successful farmer, was ready to support her to do a masters in Australia.

The Monday she took her own life, three years ago, she had hopped on her scooter to go to work as usual. “She was all smiles,” her father, Kirni Bhoopani, says.

It was only when police reviewed Mounika’s phone and bank statements that they found out she had borrowed from 55 different loan apps. It started with a loan of 10,000 rupees ($120; £100) and spiralled to more than 30 times that. By the time she decided to kill herself, she had paid back more than 300,000 rupees ($3,600; £2,960).

Police say the apps harassed her with calls and vulgar messages – and had started messaging her contacts.

On the day that she died Mounika was due to travel to her best friend’s wedding (pic BBC)

Mounika’s room is now a makeshift shrine. Her government ID card hangs by the door, the bag her mum packed for a wedding still lying there.

The thing that upsets her father the most is that she hadn’t told him what was going on. “We could have easily arranged the money,” he says, wiping tears from his eyes. He’s furious at the people who did this. As he was taking his daughter’s body home from the hospital her phone rang and he answered to an obscenity-laden rant. “They told us she has to pay,” he says. “We told them she was dead.” He wondered who these monsters could be.

Hari – not his real name – worked at a call centre doing recovery for one of the apps Mounika had borrowed from. The pay was good but by the time Mounika died he was already feeling uneasy about what he was part of. Although he claims not to have made abusive calls himself – he says he was in the team that made initial polite calls – he told us managers instructed staff to abuse and threaten people.

The agents would send messages to a victim’s contacts, painting the victim as a fraud and a thief. “Everyone has a reputation to maintain in front of their family. No-one is going to spoil that reputation for the measly sum of 5,000 rupees,” he says.

Once a payment had been made the system would ping “Success!” and they would move on to the next client.

When clients started threatening to take their own lives nobody took it seriously – then the suicides started happening. The staff called their boss, Parshuram Takve, to ask if they should stop. The following day Takve appeared in the office. He was angry. “He said, ‘Do what you’re told and make recoveries,'” Hari says. So they did. A few months later, Mounika was dead.

Takve was ruthless. But he wasn’t running this operation alone. Sometimes, Hari says, the software interface would switch to Chinese without warning. Takve was married to a Chinese woman called Liang Tian Tian. Together, they had set up the loan recovery business, Jiyaliang, in Pune, where Hari worked.

Liang Tian Tian and Parshuram Takve in their police mugshots (pic BBC)

In December 2020, Takve and Liang were arrested by police investigating a case of harassment and released on bail a few months later. In April 2022 they were charged with extortion, intimidation and abetment of suicide. By the end of the year they were on the run.

We couldn’t track down Takve. But when we investigated the apps Jiyaliang worked for, it led us to a Chinese businessman called Li Xiang. He has no online presence, but we found a phone number linked to one of his employees and, posing as investors, set up a meeting with Li.

With his face shoved uncomfortably close to the camera, he bragged about his businesses in India. “We are still operating now, just not letting Indians know we are a Chinese company,” he said.

Back in 2021, two of Li’s companies had been raided by Indian police investigating harassment by loan apps. Their bank accounts had been frozen. “You need to understand that because we aim to recover our investment quickly, we certainly don’t pay local taxes, and the interest rates we offer violate local laws,” he says.

Li told us his company has its own loan apps in India, Mexico and Colombia. He claimed to be an industry leader in risk control and debt collection services in South East Asia, and is now expanding across Latin America and Africa – with more than 3,000 staff in Pakistan, Bangladesh and India ready to provide “post-loan services”.

Then he explained what his company does to recover loans. “If you don’t repay, we may add you on WhatsApp, and on the third day, we will call and message you on WhatsApp at the same time, and call your contacts. Then, on the fourth day, if your contacts don’t pay, we have specific detailed procedures.

“We access his call records and capture a lot of his information. Basically, it’s like he’s naked in front of us.”

Bhoomi Sinha could handle the harassment, the threats, the abuse and the exhaustion – but not the shame of being linked to that pornographic image.

“That message actually stripped me naked in front of the entire world,” she says. “I lost my self-respect, my morality, my dignity, everything in a second.”

It was shared with lawyers, architects, government officials, elderly relatives and friends of her parents – people who would never look at her in the same way again. “It has tarnished the core of me, like if you join a broken glass, there will still be cracks on it,” she says.

She has been ostracised by neighbours in the community she has lived in for 40 years. “As of today, I have no friends. It’s just me I guess,” she says with a sad chuckle.

Some of her family still don’t speak to her. And she constantly wonders whether the men she works with are picturing her naked.

The morning that her daughter Astha found her she was at her lowest ebb. But it was also the moment she decided to fight back. “I don’t want to die like this,” she decided.

She filed a police report but has heard nothing since. All she could do was change her number and get rid of her sim card – and when Astha started receiving calls her daughter destroyed hers too. She told friends, family and colleagues to ignore the calls and messages and, eventually, they all but stopped.

Bhoomi found support in her sisters, her boss and an online community of others abused by loan apps. But mostly, she found strength in her daughter.

“I must have done something good to be given a daughter like this,” she says. “If she hadn’t stood by me then I would have been one of the many people who’ve killed themselves because of loan apps.”

We put the allegations in this report to Asan Loan – and also, through contacts, to Liang Tian Tian and Parshuram Takve, who are in hiding. Neither the company nor the couple responded.

When asked for comment, Li Xiang told the BBC that he and his companies comply with all local laws and regulations, have never run predatory loan apps, have ceased collaboration with Jiyaliang, the loan recovery company run by Liang Tian Tian and Parshuram Takve, and do not collect or use customers’ contact information.

He said his loan recovery call centres adhere to strict standards and he denied profiting from the suffering of ordinary Indians.

Majesty Legal Services deny using customers’ contacts to recover loans. They told us their agents are instructed to avoid abusive or threatening calls, and any violation of the company’s policies results in dismissal.

(BBC)

Features

Reconciliation, Mood of the Nation and the NPP Government

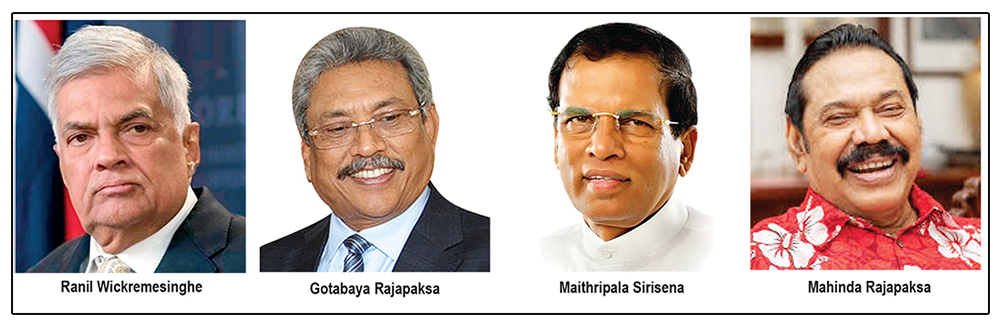

From the time the search for reconciliation began after the end of the war in 2009 and before the NPP’s victories at the presidential election and the parliamentary election in 2024, there have been four presidents and four governments who variously engaged with the task of reconciliation. From last to first, they were Ranil Wickremesinghe, Gotabaya Rajapaksa, Maithripala Sirisena and Mahinda Rajapaksa. They had nothing in common between them except they were all different from President Anura Kumara Dissanayake and his approach to reconciliation.

The four former presidents approached the problem in the top-down direction, whereas AKD is championing the building-up approach – starting from the grassroots and spreading the message and the marches more laterally across communities. Mahinda Rajapaksa had his ‘agents’ among the Tamils and other minorities. Gotabaya Rajapaksa was the dummy agent for busybodies among the Sinhalese. Maithripala Sirisena and Ranil Wickremesinghe operated through the so called accredited representatives of the Tamils, the Muslims and the Malaiayaka (Indian) Tamils. But their operations did nothing for the strengthening of institutions at the provincial and the local levels. No did they bother about reaching out to the people.

As I recounted last week, the first and the only Northern Provincial Council election was held during the Mahinda Rajapaksa presidency. That nothing worthwhile came out of that Council was not mainly the fault of Mahinda Rajapaksa. His successors, Maithripala Sirisena and Ranil Wickremesinghe as Prime Minister, with the TNA acceding as a partner of their government, cancelled not only the NPC but also all PC elections and indefinitely suspended the functioning of the country’s nine elected provincial councils. Now there are no elected councils, only colonial-style governors and their secretaries.

Hold PC Elections Now

And the PC election can, like so many other inherited rotten cans, is before the NPP government. Is the NPP government going to play footsie with these elections or call them and be done with it? That is the question. Here are the cons and pros as I see them.

By delaying or postponing the PC elections President AKD and the NPP government are setting themselves up to be justifiably seen as following the cynical playbook of the former interim President Ranil Wickremesinghe. What is the point, it will be asked, in subjecting Ranil Wickremesinghe to police harassment over travel expenses while following his playbook in postponing elections?

Come to think of it, no VVIP anywhere can now whine of unfair police arrest after what happened to the disgraced former prince Andrew Mountbatten Windsor in England on Thursday. Good for the land where habeas corpus and due process were born. The King did not know what was happening to his kid brother, and he was wise enough to pronounce that “the law must take its course.” There is no course for the law in Trump’s America where Epstein spun his webs around rich and famous men and helpless teenage girls. Only cover up. Thanks to his Supreme Court, Trump can claim covering up to be a core function of his presidency, and therefore absolutely immune from prosecution. That is by the way.

Back to Sri Lanka, meddling with elections timing and process was the method of operations of previous governments. The NPP is supposed to change from the old ways and project a new way towards a Clean Sri Lanka built on social and ethical pillars. How does postponing elections square with the project of Clean Sri Lanka? That is the question that the government must be asking itself. The decision to hold PC elections should not be influenced by whether India is not asking for it or if Canada is requesting it.

Apart from it is the right thing do, it is also politically the smart thing to do.

The pros are aplenty for holding PC elections as soon it is practically possible for the Election Commission to hold them. Parliament can and must act to fill any legal loophole. The NPP’s political mojo is in the hustle and bustle of campaigning rather than in the sedentary business of governing. An election campaign will motivate the government to re-energize itself and reconnect with the people to regain momentum for the remainder of its term.

While it will not be possible to repeat the landslide miracle of the 2024 parliamentary election, the government can certainly hope and strive to either maintain or improve on its performance in the local government elections. The government is in a better position to test its chances now, before reaching the halfway mark of its first term in office than where it might be once past that mark.

The NPP can and must draw electoral confidence from the latest (February 2026) results of the Mood of the Nation poll conducted by Verité Research. The government should rate its chances higher than what any and all of the opposition parties would do with theirs. The Mood of the Nation is very positive not only for the NPP government but also about the way the people are thinking about the state of the country and its economy. The government’s approval rating is impressively high at 65% – up from 62% in February 2025 and way up from the lowly 24% that people thought of the Ranil-Rajapaksa government in July 2024. People’s mood is also encouragingly positive about the State of the Economy (57%, up from 35% and 28%); Economic Outlook (64%, up from 55% and 30%); the level of Satisfaction with the direction of the country( 59%, up from 46% and 17%).

These are positively encouraging numbers. Anyone familiar with North America will know that the general level of satisfaction has been abysmally low since the Iraq war and the great economic recession. The sour mood that invariably led to the election of Trump. Now the mood is sourer because of Trump and people in ever increasing numbers are looking for the light at the end of the Trump tunnel. As for Sri Lanka, the country has just come out of the 20-year long Rajapaksa-Ranil tunnel. The NPP represents the post Rajapaksa-Ranil era, and the people seem to be feeling damn good about it.

Of course, the pundits have pooh-poohed the opinion poll results. What else would you expect? You can imagine which twisted way the editorial keypads would have been pounded if the government’s approval rating had come under 50%, even 49.5%. There may have even been calls for the government to step down and get out. But the government has its approval rating at 65% – a level any government anywhere in the Trump-twisted world would be happy to exchange without tariffs. The political mood of the people is not unpalpable. Skeptical pundits and elites will have to only ask their drivers, gardeners and their retinue of domestics as to what they think of AKD, Sajith or Namal. Or they can ride a bus or take the train and check out the mood of fellow passengers. They will find Verité’s numbers are not at all far-fetched.

Confab Threats

The government’s plausible popularity and the opposition’s obvious weaknesses should be good enough reason for the government to have the PC elections sooner than later. A new election campaign will also provide the opportunity not only for the government but also for the opposition parties to push back on the looming threat of bad old communalism making a comeback. As reported last week, a “massive Sangha confab” is to be held at 2:00 PM on Friday, February 20th, at the All Ceylon Buddhist Congress Headquarters in Colombo, purportedly “to address alleged injustices among monks.”

According to a warning quote attributed to one of the organizers, Dambara Amila Thero, “never in the history of Sri Lanka has there been a government—elected by our own votes and the votes of the people—that has targeted and launched such systematic attacks against the entire Sasana as this one.” That is quite a mouthful and worthier practitioners of Buddhism have already criticized this unconvincing claim and its being the premise for a gathering of spuriously disaffected monks. It is not difficult to see the political impetus behind this confab.

The impetus obviously comes from washed up politicians who have tried every slogan from – L-board-economists, to constitutional dictatorship, to save-our children from sex-education fear mongering – to attack the NPP government and its credibility. They have not been able to stick any of that mud on the government. So, the old bandicoots are now trying to bring back the even older bogey of communalism on the pretext that the NPP government has somewhere, somehow, “targeted and launched such systematic attacks against the entire Sasana …”

By using a new election campaign to take on this threat, the government can turn the campaign into a positively educational outreach. That would be consistent with the President’s and the government’s commitment to “rebuild Sri Lanka” on the strength of national unity without allowing “division, racism, or extremism” to undermine unity. A potential election campaign that takes on the confab of extremists will also provide a forum and an opportunity for the opposition parties to let their positions known. There will of course be supporters of the confab monks, but hopefully they will be underwhelming and not overwhelming.

For all their shortcomings, Sajith Premadasa and Namal Rajapaksa belong to the same younger generation as Anura Kumara Dissanayake and they are unlikely to follow the footsteps of their fathers and fan the flames of communalism and extremism all over again. Campaigning against extremism need not and should not take the form of disparaging and deriding those who might be harbouring extremist views. Instead, the fight against extremism should be inclusive and not exclusive, should be positively educational and appeal to the broadest cross-section of people. That is the only sustainable way to fight extremism and weaken its impacts.

Provincial Councils and Reconciliation

In the framework of grand hopes and simple steps of reconciliation, provincial councils fall somewhere in between. They are part of the grand structure of the constitution but they are also usable instruments for achieving simple and practical goals. Obviously, the Northern Provincial Council assumes special significance in undertaking tasks associated with reconciliation. It is the only jurisdiction in the country where the Sri Lankan Tamils are able to mind their own business through their own representatives. All within an indivisibly united island country.

But people in the north will not be able to do anything unless there is a provincial council election and a newly elected council is established. If the NPP were to win a majority of seats in the next Northern Provincial Council that would be a historic achievement and a validation of its approach to national reconciliation. On the other hand, if the NPP fails to win a majority in the north, it will have the opportunity to demonstrate that it has the maturity to positively collaborate from the centre with a different provincial government in the north.

The Eastern Province is now home to all three ethnic groups and almost in equal proportions. Managing the Eastern Province will an experiential microcosm for managing the rest of the country. The NPP will have the opportunity to prove its mettle here – either as a governing party or as a responsible opposition party. The Central Province and the Badulla District in the Uva Province are where Malaiyaka Tamils have been able to reconstitute their citizenship credentials and exercise their voting rights with some meaningful consequence. For decades, the Malaiyaka Tamils were without voting rights. Now they can vote but there is no Council to vote for in the only province and district they predominantly leave. Is that fair?

In all the other six provinces, with the exception of the Greater Colombo Area in the Western Province and pockets of Muslim concentrations in the South, the Sinhalese predominate, and national politics is seamless with provincial politics. The overlap often leads to questions about the duplication in the PC system. Political duplication between national and provincial party organizations is real but can be avoided. But what is more important to avoid is the functional duplication between the central government in Colombo and the provincial councils. The NPP governments needs to develop a different a toolbox for dealing with the six provincial councils.

Indeed, each province regardless of the ethnic composition, has its own unique characteristics. They have long been ignored and smothered by the central bureaucracy. The provincial council system provides the framework for fostering the unique local characteristics and synthesizing them for national development. There is another dimension that could be of special relevance to the purpose of reconciliation.

And that is in the fostering of institutional partnerships and people to-people contacts between those in the North and East and those in the other Provinces. Linkages could be between schools, and between people in specific activities – such as farming, fishing and factory work. Such connections could be materialized through periodical visits, sharing of occupational challenges and experiences, and sports tournaments and ‘educational modules’ between schools. These interactions could become two-way secular pilgrimages supplementing the age old religious pilgrimages.

Historically, as Benedict Anderson discovered, secular pilgrimages have been an important part of nation building in many societies across the world. Read nation building as reconciliation in Sri Lanka. The NPP government with its grassroots prowess is well positioned to facilitate impactful secular pilgrimages. But for all that, there must be provincial councils elections first.

by Rajan Philips

Features

Barking up the wrong tree

The idiom “Barking up the wrong tree” means pursuing a mistaken line of thought, accusing the wrong person, or looking for solutions in the wrong place. It refers to hounds barking at a tree that their prey has already escaped from. This aptly describes the current misplaced blame for young people’s declining interest in religion, especially Buddhism.

It is a global phenomenon that young people are increasingly disengaged from organized religion, but this shift does not equate to total abandonment, many Gen Z and Millennials opt for individual, non-institutional spirituality over traditional structures. However, the circumstances surrounding Buddhism in Sri Lanka is an oddity compared to what goes on with religions in other countries. For example, the interest in Buddha Dhamma in the Western countries is growing, especially among the educated young. The outpouring of emotions along the 3,700 Km Peace March done by 16 Buddhist monks in USA is only one example.

There are good reasons for Gen Z and Millennials in Sri Lanka to be disinterested in Buddhism, but it is not an easy task for Baby Boomer or Baby Bust generations, those born before 1980, to grasp these bitter truths that cast doubt on tradition. The two most important reasons are: a) Sri Lankan Buddhism has drifted away from what the Buddha taught, and b) The Gen Z and Millennials tend to be more informed and better rational thinkers compared to older generations.

This is truly a tragic situation: what the Buddha taught is an advanced view of reality that is supremely suited for rational analyses, but historical circumstances have deprived the younger generations over centuries from knowing that truth. Those who are concerned about the future of Buddhism must endeavor to understand how we got here and take measures to bridge that information gap instead of trying to find fault with others. Both laity and clergy are victims of historical circumstances; but they have the power to shape the future.

First, it pays to understand how what the Buddha taught, or Dhamma, transformed into 13 plus schools of Buddhism found today. Based on eternal truths he discovered, the Buddha initiated a profound ethical and intellectual movement that fundamentally challenged the established religious, intellectual, and social structures of sixth-century BCE India. His movement represented a shift away from ritualistic, dogmatic, and hierarchical systems (Brahmanism) toward an empirical, self-reliant path focused on ethics, compassion, and liberation from suffering. When Buddhism spread to other countries, it transformed into different forms by absorbing and adopting the beliefs, rituals, and customs indigenous to such land; Buddha did not teach different truths, he taught one truth.

Sri Lankan Buddhism is not any different. There was resistance to the Buddha’s movement from Brahmins during his lifetime, but it intensified after his passing, which was responsible in part for the disappearance of Buddhism from its birthplace. Brahminism existed in Sri Lanka before the arrival of Buddhism, and the transformation of Buddhism under Brahminic influences is undeniable and it continues to date.

This transformation was additionally enabled by the significant challenges encountered by Buddhism during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries (Wachissara 1961, Mirando 1985). It is sad and difficult to accept, but Buddhism nearly disappeared from the land that committed the Teaching into writing for the first time. During these tough times, with no senior monks to perform ‘upasampada,’ quasi monks who had not been admitted to the order – Ganninanses, maintained the temples. Lacking any understanding of the doctrinal aspects of Buddha’s teaching, they started performing various rituals that Buddha himself rejected (Rahula 1956, Marasinghe 1974, Gombrich 1988, 1997, Obeyesekere 2018).

The agrarian population had no way of knowing or understanding the teachings of the Buddha to realize the difference. They wanted an easy path to salvation, some power to help overcome an illness, protect crops from pests or elements; as a result, the rituals including praying and giving offerings to various deities and spirits, a Brahminic practice that Buddha rejected in no uncertain terms, became established as part of Buddhism.

This incorporation of Brahminic practices was further strengthened by the ascent of Nayakkar princes to the throne of Kandy (1739–1815) who came from the Madurai Nayak dynasty in South India. Even though they converted to Buddhism, they did not have any understanding of the Teaching; they were educated and groomed by Brahminic gurus who opposed Buddhism. However, they had no trouble promoting the beliefs and rituals that were of Brahminic origin and supporting the institution that performed them. By the time British took over, nobody had any doubts that the beliefs, myths, and rituals of the Sinhala people were genuine aspects of Buddha’s teaching. The result is that today, Sri Lankan Buddhists dare doubt the status quo.

The inclusion of Buddhist literary work as historical facts in public education during the late nineteenth century Buddhist revival did not help either. Officially compelling generations of students to believe poetic embellishments as facts gave the impression that Buddhism is a ritualistic practice based on beliefs.

This did not create any conflict in the minds of 19th agrarian society; to them, having any doubts about the tradition was an unthinkable, unforgiving act. However, modernization of society, increased access to information, and promotion of rational thinking changed things. Younger generations have begun to see the futility of current practices and distance themselves from the traditional institution. In fact, they may have never heard of it, but they are following Buddha’s advice to Kalamas, instinctively. They cannot be blamed, instead, their rational thinking must be appreciated and promoted. It is the way the Buddha’s teaching, the eternal truth, is taught and practiced that needs adjustment.

The truths that Buddha discovered are eternal, but they have been interpreted in different ways over two and a half millennia to suit the prevailing status of the society. In this age, when science is considered the standard, the truth must be viewed from that angle. There is nothing wrong or to be afraid of about it for what the Buddha taught is not only highly scientific, but it is also ahead of science in dealing with human mind. It is time to think out of the box, instead of regurgitating exegesis meant for a bygone era.

For example, the Buddhist model of human cognition presented in the formula of Five Aggregates (pancakkhanda) provides solutions to the puzzles that modern neuroscience and philosophers are grappling with. It must be recognized that this formula deals with the way in which human mind gathers and analyzes information, which is the foundation of AI revolution. If the Gen Z and Millennial were introduced to these empirical aspects of Dhamma, they would develop a genuine interest in it. They thrive in that environment. Furthermore, knowing Buddha’s teaching this way has other benefits; they would find solutions to many problems they face today.

Buddha’s teaching is a way to understand nature and the humans place in it. One who understands this can lead a happy and prosperous life. As the Dhammapada verse number 160 states – “One, indeed, is one’s own refuge. Who else could be one’s own refuge?” – such a person does not depend on praying or offering to idols or unknown higher powers for salvation, the Brahminic practice. Therefore, it is time that all involved, clergy and laity, look inwards, and have the crucial discussion on how to educate the next generation if they wish to avoid Sri Lankan Buddhism suffer the same fate it did in India.

by Geewananda Gunawardana, Ph.D.

Features

Why does the state threaten Its people with yet another anti-terror law?

The Feminist Collective for Economic Justice (FCEJ) is outraged at the scheme of law proposed by the government titled “Protection of the State from Terrorism Act” (PSTA). The draft law seeks to replace the existing repressive provisions of the Prevention of Terrorism Act 1979 (PTA) with another law of extraordinary powers. We oppose the PSTA for the reason that we stand against repressive laws, normalization of extraordinary executive power and continued militarization. Ruling by fear destroys our societies. It drives inequality, marginalization and corruption.

Our analysis of the draft PSTA is that it is worse than the PTA. It fails to justify why it is necessary in today’s context. The PSTA continues the broad and vague definition of acts of terrorism. It also dangerously expands as threatening activities of ‘encouragement’, ‘publication’ and ‘training’. The draft law proposes broad powers of arrest for the police, introduces powers of arrest to the armed forces and coast guards, and continues to recognize administrative detention. Extremely disappointing is the unjustifiable empowering of the President to make curfew order and to proscribe organizations for indefinite periods of time, the power of the Secretary to the Ministry of Defence to declare prohibited places and police officers in the rank of Deputy Inspector Generals are given the power to secure restriction orders affecting movement of citizens. The draft also introduces, knowing full well the context of laws delays, the legal perversion of empowering the Attorney General to suspend prosecution for 20 years on the condition that a suspect agrees to a form of punishment such as public apology, payment of compensation, community service, and rehabilitation. Sri Lanka does not need a law normalizing extraordinary power.

We take this moment to remind our country of the devastation caused to minoritized populations under laws such as the PTA and the continued militarization, surveillance and oppression aided by rapidly growing security legislation. There is very limited space for recovery and reconciliation post war and also barely space for low income working people to aspire to physical, emotional and financial security. The threat posed by even proposing such an oppressive law as the PSTA is an affront to feminist conceptions of human security. Security must be recognized at an individual and community level to have any meaning.

The urgent human security needs in Sri Lanka are undeniable – over 50% of households in the country are in debt, a quarter of the population are living in poverty, over 30% of households experience moderate/severe food insecurity issues, the police receive over 100,000 complaints of domestic violence each year. We are experiencing deepening inequality, growing poverty, assaults on the education and health systems of the country, tightening of the noose of austerity, the continued failure to breathe confidence and trust towards reconciliation, recovery, restitution post war, and a failure to recognize and respond to structural discrimination based on gender, race and class, religion. State security cannot be conceived or discussed without people first being safe, secure, and can hope for paths towards developing their lives without threat, violence and discrimination. One year into power and there has been no significant legislative or policy moves on addressing austerity, rolling back of repressive laws, addressing domestic and other forms of violence against women, violence associated with household debt, equality in the family, equality of representation at all levels, and the continued discrimination of the Malaiyah people.

The draft PSTA tells us that no lessons have been learnt. It tells us that this government intends to continue state tools of repression and maintain militarization. It is hard to lose hope within just a year of a new government coming into power with a significant mandate from the people to change the system, and yet we are here. For women, young people, children and working class citizens in this country everyday is a struggle, everyday is a minefield of threats and discrimination. We do not need another threat in the form of the PSTA. Withdraw the PSTA now!

The Feminist Collective for Economic Justice is a collective of feminist economists, scholars, feminist activists, university students and lawyers that came together in April 2022 to understand, analyze and give voice to policy recommendations based on lived realities in the current economic crisis in Sri Lanka.

Please send your comments to – feministcollectiveforjustice@gmail.com

-

Features19 hours ago

Features19 hours agoWhy does the state threaten Its people with yet another anti-terror law?

-

Business7 days ago

Business7 days agoMinistry of Brands to launch Sri Lanka’s first off-price retail destination

-

Features19 hours ago

Features19 hours agoVictor Melder turns 90: Railwayman and bibliophile extraordinary

-

Features19 hours ago

Features19 hours agoReconciliation, Mood of the Nation and the NPP Government

-

Latest News2 days ago

Latest News2 days agoNew Zealand meet familiar opponents Pakistan at spin-friendly Premadasa

-

Features19 hours ago

Features19 hours agoVictor, the Friend of the Foreign Press

-

Latest News2 days ago

Latest News2 days agoTariffs ruling is major blow to Trump’s second-term agenda

-

Latest News2 days ago

Latest News2 days agoECB push back at Pakistan ‘shadow-ban’ reports ahead of Hundred auction