Opinion

How the plot would unfold

1962 coup – Part IV

A group of senior Police and Military officers attempted to overthrow the Sirimavo Bandaranaike Government. They were driven by three critical events in the years leading up to January 1962. The coup participants belonged to the Westernised urban middle class who were alarmed at the undermining of the secular plural state and government.

Continued from yesterday

By Jayantha Somasundaram

The coup d’état would commence at midnight Saturday, 27 January, 1962. Lieutenant Colonel Noel Mathysz, Commanding Officer, Ceylon Electrical and Mechanical Engineers would take the Central Telegraph Office, Major Weerasena Rajapakse, Ceylon Armoured Corps would send four armoured vehicles to guard the Governor-General’s residence, Queen’s House, and another four to the Kirillapone Bridge to secure a key access point into Colombo. Captain J.A.R. Felix would guard Lake House.

The Prime Minister was scheduled to return to Colombo on the 27 after a visit to Kataragama. At Hunugama on the A2 Road, Superintendent of Police, Southern Province (East), David Thambyah would intercept her and place her under arrest.

While the Coup plot included officers and former officers from the Police, the Army and the Navy, the heads of these services were not participants. The sympathies of the Army Commander Major General Winston Wijeyakoon had been unclear to the conspirators prior to the Coup. It is claimed that he had been sounded out obliquely about moving against the government, but the Coup plotters felt that he was too cautious and would “act against the regime only when the situation deteriorated to the point of anarchy.”

The Inspector General of Police Walter Abeykoon was a Civil Servant from outside the Police Force. Moreover, specifically appointed by S.W.R.D. Bandaranaike, he was considered an SLFP loyalist. The acting Captain of the Royal Ceylon Navy Commodore Rajanathan Kadirgamar was seen as a supporter of Sirimavo Bandaranaike. So, on the night of the Coup, Kadirgamar was shadowed by the conspirators in order to be aware of his movements and location. The Royal Ceylon Air Force was commanded by a Royal Air Force-seconded officer, Air Commodore J.L. Barker, who was presumed to be indifferent to domestic political issues.

Mastermind

The Coup participants identified different leaders as the prime movers. According to Royce de Mel, Derek de Saram was the person who masterminded it. While according to Douglas Liyanage “everyone knew that the brains behind the Coup was Sidney de Zoysa, although F.C. De Saram took personal responsibility,” once they were apprehended.

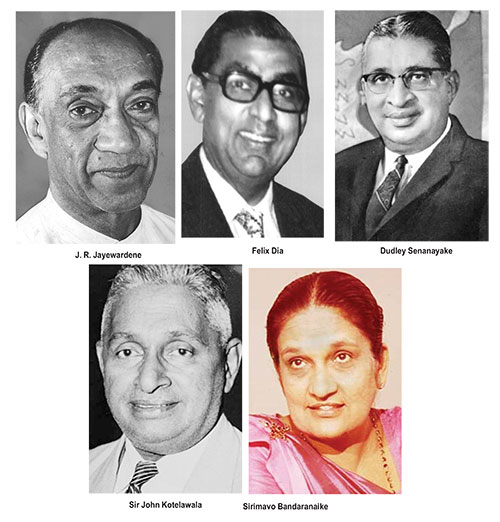

Former President J.R. Jayewardene claimed that in April 1966 at Kandawala (Kotalawala’s then residence and the current Military Academy) former Prime Minister Sir John Kotelawala informed him that both former Prime Minister Dudley Senanayake and he “had been involved in the planning of the Coup.” According to Jayawardene the Coup leaders had discussed the plot with Kotelawala who had advised them to get the support of Dudley Senanayake and Sir Oliver Goonetilleke. Both Sir John and Dudley had participated in a meeting at Borella to finalise the Coup, followed by a further meeting at Kandawala on the 26, with Dudley presiding. While a few weeks before his death in 1988 Douglas Liyanage “confirmed that Senanayake, Kotalawala and Goonetilleke had been in the know of it” (K. M. de Silva and Howard Wriggins in J. R. Jayewardene of Sri Lanka Vol II ).

In 1958 during the anti-Tamil riots, Prime Minister Bandaranaike had been unwilling to act firmly against the rioters and as a consequence the violence had spread. This compelled the Governor-General to declare a State of Emergency, deploy the armed forces and take command of security operations. The Coup was premised on a similar situation, that mindful of the severity of the political crisis, the Governor-General would agree to take political control once the Bandaranaike Government had been overthrown.

Take Post order

The first step in the execution of the Coup would be taken by CC ‘Jungle’ Dissanayake who in his capacity as DIG Range I which covered the city of Colombo would issue a Take Post order to officers in his range at 2200 hours Saturday. He had instructed all the Coup participants to be in uniform.

In response the first operation would be carried out by ASP Traffic Bede Johnpillai who would get the Police to secure within half an hour all entry points into Colombo. Police patrol cars would then go around Colombo announcing the imposition of a curfew which would commence at midnight. They would be backed by troops from the 2nd Volunteer Ceylon Signal Corps equipped with radio transmitters enabling the Coup Commanders to monitor events across the city.

Soldiers would now take up positions across the city, seizing and securing key points and armoured vehicles would be deployed at strategic entry points. Because of the highly unstable labour and political situation which had been deteriorating over the past months, and because the military had been inducted into many facets of normal civilian life, from unloading cargo at the Colombo Port to imprisoning Tamil parliamentarians at military bases, a heightened presence of troops and their performing what normally were non-military duties were expected neither to attract attention nor be construed as abnormal or cause for alarm.

Before any of these plans would be implemented though, a premature arrest had been made. At about 10:00 pm that night SP (Southern Province) Elster Perera with a team from the Galle Police arrested the LSSP MP for Baddegama, Neal de Alwis, Felix Dias’ uncle by marriage.

Meanwhile, unknown to the other conspirators, SP Colombo Stanley Senanayake had got in touch with his father-in-law Patrick de S Kularatne MP. Kularatne met the IGP Walter Abeykoon at the Orient Club on Saturday evening and notified him of the plot; he also informed Felix Dias.

Thwarting the Coup

Felix Dias promptly initiated counter measures to thwart the Coup. He briefed the Prime Minister, who for reasons unconnected with the Coup had cancelled her Kataragama trip. Positioning himself at Temple Trees he summoned the IGP who thereupon sent the following radio message to Police Stations, island-wide:

“To All OICC Divisions and Districts: From the IGP: Please don’t carry out whatever instructions of a special nature that you have received from your DIG. Be in readiness to carry out orders only from the IGP.”

This was followed by Colonel Sepala Attygalle, commander 1st Reconnaissance Regiment, Ceylon Armoured Corps instructing Major Weerasena Rajapakse to send armoured vehicles to guard Temple Trees. And at 1.30 am on 28 morning 300 troops supported by Bren gun carriers surrounded Jungle Dissanayake’s Longden Place residence and took him into custody.

Operation Holdfast had been

checkmated.

Thirty suspects were arrested of whom 24 defendants were tried before Chief Justice M.C. Sansoni, Justice H.N.G Fernando and Justice L.B. de Silva who tried the case without jury. They did so under The Criminal Law (Special Provisions) Act, No. 1 of 1962 which was passed by Parliament after the plot was uncovered. Thirteen were regular or volunteer Army officers, six were gazetted police officers. Other officers who were suspect were sent on compulsory leave or forced to resign.

The Trial-at-Bar found 11 suspects guilty of waging war against the Queen and sentenced each of them to 10 years in prison and the confiscation of all property. On appeal to the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council they were released on a point of law. The Privy Council’s verdict of 5 December, 1965 stated that “The Ceylon Government has no powers to pass the new law styled The Criminal Law (Special Provisions) Act No. 1 of 1962, which is ultra-vires, bad in law and had denied a fair trial.”

(Concluded)

Opinion

Missing 52%: Why Women are absent from Pettah’s business landscape

Walking through Pettah market in Colombo, I have noticed something both obvious and troubling. Shop after shop sells bags, shoes, electronics, even sarees, and yet all shops are owned and run by men. Even businesses catering exclusively to women, like jewelry stores and bridal boutiques, have men behind the counter. This is not just my observation but it’s a reality where most Sri Lankans have observed as normal. What makes this observation more important is when we examine the demographics where women population constitute approximately 52% of Sri Lanka’s population, but their representation as business owners remains significantly low. According to the Global Entrepreneurship Monitor 2023 report, Sri Lanka’s Total Early Stage Entrepreneurial Activity rate for women is just 8.2%, compared to 14.7% for men.

Despite of being the majority, women are clearly underrepresented in the entrepreneurial aspect. This mismatch between population size and economic participation create a question that why aren’t more women starting ventures? The answer is not about capability or intelligence. Rather, it’s deeply in social and cultural barriers that have been shaping women’s mindsets for generations. From childhood, many Sri Lankan girls are raised to believe that their primary role is as homemakers.

In families, schools, and even universities, the message has been same or slightly different, woman’s success is measured by how well she manages a household, not by her ability to generate income or lead a business. Financial independence is rarely taught as essential for women the way it has been for men. Over time, this messaging gets internalised. Many women grew up without ever being encouraged to think seriously about ownership, leadership, or earning their own money. These cultural influences eventually manifest as psychological barriers as well.

Years of conditioning have led many skilled women to develop what researchers call “imposter syndrome”, a persistent fear of failure and feel that they don’t deserve success kind of feeling. Even when they have the right skills and resources, self-doubt holds them back. They question whether they can run a business independently or not. Whether they will be taken seriously, whether they are making the right choice. This does not mean that women should leave their families or reject traditional roles. But lack of thinking in a confident way and make bold decisions has real consequences. Many talented women either never start a business or limit themselves to small, informal ventures that barely survive. This is not about men versus women. It’s about the economic cost of underutilising 52% of the population. If our country is genuinely serious about sustainable growth. we must build an inclusive entrepreneurial ecosystem through confidence building programs, better finance access to women, and a long term societal mindset shift. Until a young girl walking through Pettah can see herself as a future shop owner rather than just a customer, we will continue to waste our country’s greatest untapped resource.

Harinivasini Hariharasarma

Department of Entrepreneurship

University of Sri Jayewardenepura

Opinion

Molten Salt Reactors

Some essential points made to indicate its future in Power Generation

The hard facts are that:

1) Coal supplies cannot last for more than 70- 100 years more at most, with the price rising as demand exceeds supply.

2) Reactor grade Uranium is in short supply, also with the price rising. The cost is comparable to burning platinum as a fuel.

3) 440 standard Uranium reactors around the world are 25-30 years old – coming to the end of their working life and need to be replaced.

4) Climate Change is increasingly making itself felt and forecasts can only be for continuing deterioration due to existing levels of CO2 being continuously added to the atmosphere. It is important to mention the more serious problems associated with the release of methane gases – a more harmful gas than CO2 – arising from several sources.

5) Air pollution (ash, chemicals, etc.) of the atmosphere by coal-fired plants is highly dangerous for human health and should be eliminated for very good health reasons. Pollution created by India travels to Sri Lankans by the NE monsoon causing widespread lung irritations and Chinese pollution travels all around the world and affects everybody.

6) Many (thousands) of new sources of electric power generation need to be built to meet increasing demand. But the waste Plutonium 239 (the Satan Stuff) material has also to be moved around each country by lorry with police escort at each stage, as it is recovered, stored, processed and formed into blocks for long term storage. The problem of security of transport for Plutonium at each stage to prevent theft becomes an impossible nightmare.

The positive strengths to Thorium Power generation are:

1) Thorium is quite abundant on the planet – 100 times more than Uranium 238, therefore supplies will last thousands of years.

2) Cleaning or refining the Thorium is not a difficult process.

3) It is not highly radioactive having a very slow rate of isotope decay. There is little danger from radiation poisoning. It can be safely stored in the open, unaffected by rain. It is not harmful when ingested.

4) The processes involved with power generation are quite different and are a lot less complex.

5) Power units can be quite small, the size of a modern detached house. One of these can be located close to each town, thus eliminating high voltage cross-country transmission lines with their huge power losses (up to 20%).

6) Thorium is ‘fertile’ not fissile: therefore, the energy cycle has to be kick-started by a source of Neutrons, e.g., fissile material, to get it started. It is definitely not as dangerous as Uranium.

7) It is “Fail – Safe”. It has walk-away safety. If the reactor overheats, cooled drain plugs unfreeze and the liquid drains away to storage tanks below. There can be no “Chernobyl/ Fukoshima” type disasters.

8) It is not a pressurized system; it works at atmospheric pressure.

9) As long as reactor temperatures are kept around 600 oC there are little effects of corrosion in the Hastalloy metal tanks, vessels and pipe work. China, it appears, has overcome the corrosion problem at high temperatures.

10) At no stage in the whole chain of operations is there an opportunity for material to be stolen and converted and used as a weapon. The waste products have a half- life of 300 years, not the millions of years for Plutonium.

11) Production of MEDICAL ISOTOPE Bismuth 213 is available to be isolated and used to fight cancer. The nastiest cancers canbe cured with this Bismuth 213 as Targetted Alpha therapy.

12) A hydrogen generation unit can be added.

This information obtained from following YouTube film clips:

1) The Liquid Fluoride Thorium Reactor – what Fusion wanted to be…

2) An unbiased look at Molten Salt Reactors

3) LFTR Chemical Processing by Kirk Sorensen

Thorium! The Way Ahead!

Priyantha Hettige

Opinion

Foreign degrees and UGC

There are three key issues regarding foreign degrees:

Recognition: Is the awarding university recognized by our UGC?

Authenticity: Is the degree genuine or bogus?

Quality: Is it a standard, credible qualification?

1. The Recognition Issue (UGC Role)

The UGC addresses the first issue. If a foreign university is listed in the Commonwealth Universities Yearbook or the International Handbook of Universities, the UGC issues a letter confirming that the university is recognized. However, it is crucial to understand that a recognized university does not automatically imply that every degree it issues is recognized.

2. The Authenticity Issue (Employer Role)

The second issue rests with the employer. It is the employer’s responsibility to send a copy of the foreign degree to the issuing university to get it authenticated. This is a straightforward verification process.

3. The Quality Assurance Gap

The third issue

—the standard and quality of the degree—has become a matter for no one. The UGC only certifies whether a foreign university is recognized; they do not assess the quality of the degree itself.

This creates a serious loophole. For example:

Does a one-year “top-up” degree meet standard criteria?

Is a degree obtained completely online considered equivalent?

Should we recognize institutions with weak invigilation, allowing students to cheat?

What about curricula that are heavy on “notional hours” but light on functional, practical knowledge?

What if the medium of instruction is English, but the graduates have no functional English proficiency?

Members of the UGC need to seriously rethink this approach. A rubber-stamp certification of a foreign university is insufficient. The current system ignores the need for strict quality assurance. When looking at the origins of some of these foreign institutions (Campuchia, Cambodia, Costa Rica, Sudan..) the intentions behind these “academic” offerings become very clear. Quality assurance is urgently needed. Foreign universities offering substandard degrees can be delisted.

M. A. Kaleel Mohammed

757@gmail.com

( Retired President of a National College of Education)

-

Features2 days ago

Features2 days agoWhy does the state threaten Its people with yet another anti-terror law?

-

Features2 days ago

Features2 days agoVictor Melder turns 90: Railwayman and bibliophile extraordinary

-

Features2 days ago

Features2 days agoReconciliation, Mood of the Nation and the NPP Government

-

Features2 days ago

Features2 days agoVictor, the Friend of the Foreign Press

-

Latest News3 days ago

Latest News3 days agoNew Zealand meet familiar opponents Pakistan at spin-friendly Premadasa

-

Features15 hours ago

Features15 hours agoLOVEABLE BUT LETHAL: When four-legged stars remind us of a silent killer

-

Latest News3 days ago

Latest News3 days agoTariffs ruling is major blow to Trump’s second-term agenda

-

Latest News3 days ago

Latest News3 days agoECB push back at Pakistan ‘shadow-ban’ reports ahead of Hundred auction