Features

GROWING COCONUTS ON ‘COCONUT LANDS’

by Chandra Arulpragasam

In 1958 I went to a lecture on coconut cultivation, because I knew nothing of the subject. The lecturer, a well-known coconut planter, started his talk with the platitude: ‘The duty of a coconut planter is to plant coconut, on coconut land’. But this set me thinking. First, who gave him the duty to plant coconuts? From his own point of view, he should be planting the crop that would give him the greatest returns, while from the country’s point of view he should be planting the crops that would provide the greatest return in terms of income, foreign exchange, employment and sustainability. Secondly, who decided that these were ‘coconut lands’? Was this not a terminology (‘tea lands’, rubber lands’, ‘coconut lands’) inherited from the British, who grew these crops because they could be grown on a plantation-scale for export?

A couple of years later (in 1960) when I headed the agriculture sector in the Department of National Planning, and again when I came with the ILO World Employment Mission to Sri Lanka in 1974, I had an opportunity to revisit these questions. If coconut was to be a mono-crop, it was important that it should meet the above criteria of greater employment, greater income and greater foreign exchange earnings compared to other crops. Coconut brings much lower financial returns than tea or rubber. As for employment, figures of 1960 showed that while one acre of tea employed 1.1 persons per acre per year, and one acre of rubber employed 0.4 persons per acre, one acre of coconut employed only 0.1 persons per acre per year. That is, only one worker was employed for every 10 acres of coconut, which was four times less than that employed in rubber and 10 times less than that employed in tea. This meant that the so called ‘coconut lands’ were under-utilizing the land not only in terms of income but also in terms of employment.

In physical terms, assuming that the coconut trees are planted in the usual spacing of 8m x 8m apart (which is accepted by the CRI as standard) and that their root system spreads only two metres around each tree (CRI stsndard), this would still leave 78 per cent of the land untouched and unutilized – the best lands in the ‘coconut triangle’.

This brings us back to the previous question. Why should these lands be called ‘coconut lands’? Is coconut the best or only crop that can be grown on them? Undoubtedly these lands are well suited for coconut, while coconuts are much in demand by our people. Not for nothing has the coconut tree been called ‘the tree of life’. But is it wise to relegate so much of our fertile lands to a relatively low-paying mono-crop? The British probably originated the nomenclature of ‘coconut lands’ when they grew coconut as a monocrop on a plantation scale, thus making it a land-extensive and labour-extensive crop, as opposed to the land-intensive and labour-intensive crops dictated by our factor endowments. Hence, this article is not against the planting of coconut: it is only against the planting of coconut as a monocrop on lands capable of yielding much more by way of intercropping.

The system of management of ‘coconut lands’ in the period 1960-1980 speaks for itself. Whereas tea and rubber estates were managed by resident estate superintendents or managers, coconut estates were ‘looked after’ by a ‘conductor’ or by a ‘watcher’, armed only with a torch and gun. The latter showed that the focus was on preventing the theft of coconuts, rather than on increasing yields or output. This locked large extents of these ‘coconut lands’ in a cycle of low expectations, low investment, low-level management, low income and low employment.

The Coconut Research Institute (CRI) in 1974 insisted that the optimum stand of coconut was 64 trees per acre, with an adequate distance (8 metres) between the individual trees and the coconut rows. It argued, on the one hand, that the growth of the intercrop would be stunted by the shade of the coconut, while insisting on the other, that the intercrop would deprive the coconuts of needed soil nutrients. After long discussions, the CRI experts ultimately agreed to the following propositions made by me in 1974.

First, it would be technically possible to inter-plant other crops during the first five years of replanting/new planting coconut without any adverse effects, since the coconut palms would be too small to block out the sunshine from the intercrop. This in itself was a big breakthrough, since an average of 9,300 acres was replanted or newly planted to coconut each year in Sri Lanka. Since intercropping would be possible for the first five years, the total acreage available for intercropping in the newly planted/replanted acreage in any particular year would be 46,500 acres (9300 acres x 5 years).

From this total should be deducted the 22 per cent of land that is actually occupied by the newly planted coconut, which would leave a net acreage of 36,000 acres for planting other crops. For purposes of comparison, this annually available acreage is more than double the extent of land opened up under land development/colonization schemes in each year, prior to the Mahaweli Scheme.

Secondly, the CRI ultimately agreed that in older stands of coconut (more than 25 years old), the trees would have grown so tall that they would not block out the sun from an inter-planted crop. It further now agrees that intercropping is possible without detriment to the coconut or its yields for 35 years of the trees’ 55 years of productive life. It is a pity that it has taken about 30 years for technical thinking to reach this conclusion!

But, thirdly, it was necessary to push the thinking even further. I argued that wider spacing between the coconut rows would result in less shade between the rows, thus enabling intercropping. The CRI in 1974 initially objected to this on the grounds that it would reduce the total number of trees per acre. But they ultimately agreed to my suggestion that if we increased the space between the rows but planted closer along the rows, the number of 64 trees per acre could still be attained, without any decrease in total production. Such further-apart spacing of coconut rows is now (40 years later) actually practised in Kerala and the Philippines, combined with intercropping. However, in Sri Lanka, although this was technically accepted in 1974, there has been little action along these lines by the Coconut Development Authority.

There remained the question of what could be grown as an inter-crop. When I travelled for FAO in Asia in the 1970s, I found pineapple, bananas, sisal, maize and manioc already inter-planted with coconut in the Philippines, and even cocoa under coconut in Indonesia, while livestock was common in most countries. Thus Sri Lanka lagged behind other South East Asian countries in this regard not only in the 1970s, but even so today.

Despite the government’s neglect, private planters in Sri Lanka have recently been adopting intercropping at an increasing pace. According to a survey done by the Coconut Research Institute in 2006, cashew was the most popular intercrop in the Dry Zone, while pineapple, betel and pepper were most popular in the Intermediate Zone. Tea, cinnamon and ginger were most popular in the Wet Zone, while bananas and livestock were common in all regions. Agro-forestry using tree crops (such as glyricidia) has also been recently recommended as a means of providing fodder for livestock, wood for fuel, biomass for fertilizer, control of erosion and soil moisture retention.

Obviously the possibilities of intercropping would be more limited in drier parts of the country with poorer soils. The inter-planting of cashew trees (pruned low) between the rows of coconut has now been adopted in the drier areas. I had also suggested (in the Short Term Implementation Programme of 1961) that groundwater was likely to be available at fairly shallow levels in the coastal areas north of Puttalam, which could be pumped up for higher value crops. I had also suggested the possibility of using windmills for such irrigation, which could be powered by the steady winds that blow during the dry season in these areas.

In 1994, I was able to revisit this question of inter-cropping under coconut in the drier areas. A women’s micro-credit in the dry north of the Puttalam District had used its loan to purchase a pump to irrigate an inter-crop on land newly planted to coconut. The women found groundwater at a depth of only four feet, which they pumped to irrigate chillie plants cultivated between the newly planted coconut rows. Their net return was Rs. 30,000 per acre within a four month period in 1994, which was more than treble the return from the adjoining coconut land for the whole year. Meanwhile, the fertilizer and water that they used for the intercrop were found to benefit the newly planted coconut too, in a win-win synergy. In the long run, the possibility of drip irrigation for coconut needs also to be considered. Such irrigation is needed only at the height of the dry season (cheap systems are now available) in order to reduce stress and increase yields.

To sum up, the Coconut Research Institute has now agreed to the following propositions that I proposed in 1961 and reiterated in 1974 (ref. ILO World Employment Mission, 1974).

· Inter-cropping between newly planted or replanted coconut can be done without prejudice to the newly planted coconut palms for the first five to six years of their life.

· In new plantings, the coconut rows could be planted farther apart, but with more trees per row, such that the total number of trees per acre will not be reduced. This would enable an inter-cop between the rows.

· Inter-planting among older coconut stands of over 25 years can be undertaken without detriment to the coconut trees or to the intercrop.

· Such intercropping can be done even in the drier regions using intercrops suited to the drier conditions, while irrigation would provide an added bonus.

· The yields of coconut actually increase because of the fertilizer and water used in the intercrop.

· There are other advantages of intercropping, such as providing biomass for fertilizer, increasing soil moisture and reducing erosion.

· The inter-crop (depending on the crop) is capable of yielding more than double the value of all the coconuts that could be produced from the same land.

Despite intercropping being both feasible and profitable, it was reported as late as 2007 that ‘in Sri Lanka, most of the coconut holdings are maintained as monocultures’ (Gunathilake, 2007). The question is why intercropping has not been more widely adopted when its feasibility and desirability were highlighted as early as 1974. The answers, in the opinion of the writer, are mainly structural and institutional.

The advantages of intercropping arise from its more intensive use of land and labour, with resultant higher returns per acre. However, the pattern of absentee ownership and management of larger estates raises the problem of supervising the casual, non-resident labourers needed for intercropping. Faced with this question, one of my estate-owner friends exploded: ‘Are you mad? The fellows (the labourers) will steal my coconuts’! Thus, although intercropping is recognized as feasible and profitable, the prevailing agrarian structure (with large holdings and absentee landlords not prepared to accept outside labour) seems to be the major factor inhibiting the wider adoption of inter-cropping on larger estates. Such estates (over 20 acres) occupied 18 per cent of the total area under coconut in 2002 (Agricultural Census of 2002).

Coconut, however, is mainly a smallholder crop in Sri Lanka, with 80 per cent of all ‘coconut lands’, covering almost 800,000 acres being made up of small holdings; 54 per cent of these are less than three acres in extent. Inter-cropping is gaining ground in this area, using mainly family labour. Although figures of comparative coconut yields between large and small coconut farms are not available for Sri Lanka, it is very likely that the coconut yields are higher in these small holdings compared to larger holdings, as proved in other countries. More importantly, the total value of agricultural production per acre in such small holdings is likely to be much higher than that in the large, well-managed coconut estates.

This is because the coconut smallholder invests more labour per unit of land to intensify and diversify his production by intercropping, in order to maximize his income. Most small coconut holdings are likely to include a papaya, banana or lime tree, some betel or pepper vines, some home-grown vegetables and some livestock. In fact, the small holder actually attains this higher level of total productivity per acre only by treating his land as much more than a ‘coconut land’.

Fortunately in more recent times, individual coconut planters in Sri Lanka have started to inter-crop on their own initiative, with encouraging results. The Coconut Research Institute has also helped by useful research into types of crops and land practices for intercropping. There has also been more forward-looking research and development abroad, in terms of ‘coconut based farming systems’ (CBFS) – a concept which is gaining ground in South India (Kerala) and some other South East Asian countries.

The purpose should not be merely to increase coconut yields, but to maximize the total productivity of these lands on a sustainable basis. This can best be achieved by a more holistic approach which seeks to develop the farming system as a whole, with each component synergistically supporting the other. While coconut would provide the pillars of such a farming system, inter-cropping would enhance its total productivity and ecological sustainability. Since coconut would still be the foundation of such a system, perhaps we could even be forgiven for referring to these lands affectionately as ‘coconut lands’!

(The writer who was a member 0f the old Ceylon Civil Service thereafter had a long career with FAO)

Features

US’ drastic aid cut to UN poses moral challenge to world

‘Adapt, shrink or die’ – thus runs the warning issued by the Trump administration to UN humanitarian agencies with brute insensitivity in the wake of its recent decision to drastically reduce to $2bn its humanitarian aid to the UN system. This is a substantial climb down from the $17bn the US usually provided to the UN for its humanitarian operations.

‘Adapt, shrink or die’ – thus runs the warning issued by the Trump administration to UN humanitarian agencies with brute insensitivity in the wake of its recent decision to drastically reduce to $2bn its humanitarian aid to the UN system. This is a substantial climb down from the $17bn the US usually provided to the UN for its humanitarian operations.

Considering that the US has hitherto been the UN’s biggest aid provider, it need hardly be said that the US decision would pose a daunting challenge to the UN’s humanitarian operations around the world. This would indeed mean that, among other things, people living in poverty and stifling material hardships, in particularly the Southern hemisphere, could dramatically increase. Coming on top of the US decision to bring to an end USAID operations, the poor of the world could be said to have been left to their devices as a consequence of these morally insensitive policy rethinks of the Trump administration.

Earlier, the UN had warned that it would be compelled to reduce its aid programs in the face of ‘the deepest funding cuts ever.’ In fact the UN is on record as requesting the world for $23bn for its 2026 aid operations.

If this UN appeal happens to go unheeded, the possibilities are that the UN would not be in a position to uphold the status it has hitherto held as the world’s foremost humanitarian aid provider. It would not be incorrect to state that a substantial part of the rationale for the UN’s existence could come in for questioning if its humanitarian identity is thus eroded.

Inherent in these developments is a challenge for those sections of the international community that wish to stand up and be counted as humanists and the ‘Conscience of the World.’ A responsibility is cast on them to not only keep the UN system going but to also ensure its increased efficiency as a humanitarian aid provider to particularly the poorest of the poor.

It is unfortunate that the US is increasingly opting for a position of international isolation. Such a policy position was adopted by it in the decades leading to World War Two and the consequences for the world as a result for this policy posture were most disquieting. For instance, it opened the door to the flourishing of dictatorial regimes in the West, such as that led by Adolph Hitler in Germany, which nearly paved the way for the subjugation of a good part of Europe by the Nazis.

If the US had not intervened militarily in the war on the side of the Allies, the West would have faced the distressing prospect of coming under the sway of the Nazis and as a result earned indefinite political and military repression. By entering World War Two the US helped to ward off these bleak outcomes and indeed helped the major democracies of Western Europe to hold their own and thrive against fascism and dictatorial rule.

Republican administrations in the US in particular have not proved the greatest defenders of democratic rule the world over, but by helping to keep the international power balance in favour of democracy and fundamental human rights they could keep under a tight leash fascism and linked anti-democratic forces even in contemporary times. Russia’s invasion and continued occupation of parts of Ukraine reminds us starkly that the democracy versus fascism battle is far from over.

Right now, the US needs to remain on the side of the rest of the West very firmly, lest fascism enjoys another unfettered lease of life through the absence of countervailing and substantial military and political power.

However, by reducing its financial support for the UN and backing away from sustaining its humanitarian programs the world over the US could be laying the ground work for an aggravation of poverty in the South in particular and its accompaniments, such as, political repression, runaway social discontent and anarchy.

What should not go unnoticed by the US is the fact that peace and social stability in the South and the flourishing of the same conditions in the global North are symbiotically linked, although not so apparent at first blush. For instance, if illegal migration from the South to the US is a major problem for the US today, it is because poor countries are not receiving development assistance from the UN system to the required degree. Such deprivation on the part of the South leads to aggravating social discontent in the latter and consequences such as illegal migratory movements from South to North.

Accordingly, it will be in the North’s best interests to ensure that the South is not deprived of sustained development assistance since the latter is an essential condition for social contentment and stable governance, which factors in turn would guard against the emergence of phenomena such as illegal migration.

Meanwhile, democratic sections of the rest of the world in particular need to consider it a matter of conscience to ensure the sustenance and flourishing of the UN system. To be sure, the UN system is considerably flawed but at present it could be called the most equitable and fair among international development organizations and the most far-flung one. Without it world poverty would have proved unmanageable along with the ills that come along with it.

Dehumanizing poverty is an indictment on humanity. It stands to reason that the world community should rally round the UN and ensure its survival lest the abomination which is poverty flourishes. In this undertaking the world needs to stand united. Ambiguities on this score could be self-defeating for the world community.

For example, all groupings of countries that could demonstrate economic muscle need to figure prominently in this initiative. One such grouping is BRICS. Inasmuch as the US and the West should shrug aside Realpolitik considerations in this enterprise, the same goes for organizations such as BRICS.

The arrival at the above international consensus would be greatly facilitated by stepped up dialogue among states on the continued importance of the UN system. Fresh efforts to speed-up UN reform would prove major catalysts in bringing about these positive changes as well. Also requiring to be shunned is the blind pursuit of narrow national interests.

Features

Egg white scene …

Hi! Great to be back after my Christmas break.

Hi! Great to be back after my Christmas break.

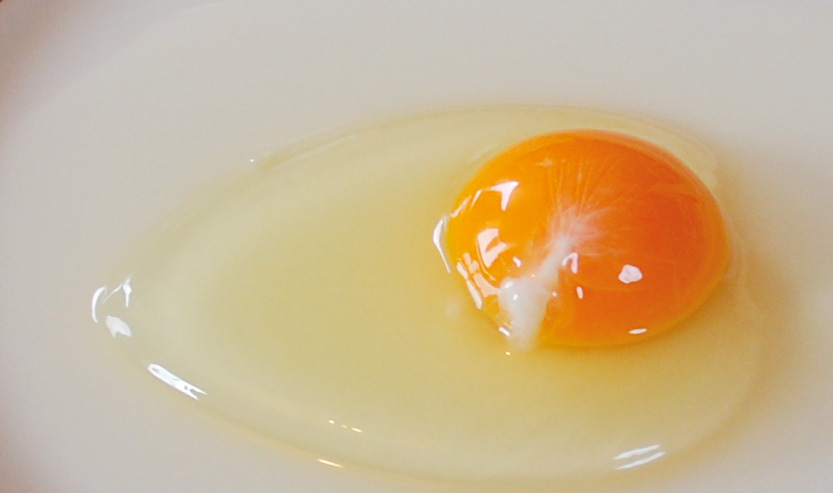

Thought of starting this week with egg white.

Yes, eggs are brimming with nutrients beneficial for your overall health and wellness, but did you know that eggs, especially the whites, are excellent for your complexion?

OK, if you have no idea about how to use egg whites for your face, read on.

Egg White, Lemon, Honey:

Separate the yolk from the egg white and add about a teaspoon of freshly squeezed lemon juice and about one and a half teaspoons of organic honey. Whisk all the ingredients together until they are mixed well.

Apply this mixture to your face and allow it to rest for about 15 minutes before cleansing your face with a gentle face wash.

Don’t forget to apply your favourite moisturiser, after using this face mask, to help seal in all the goodness.

Egg White, Avocado:

In a clean mixing bowl, start by mashing the avocado, until it turns into a soft, lump-free paste, and then add the whites of one egg, a teaspoon of yoghurt and mix everything together until it looks like a creamy paste.

Apply this mixture all over your face and neck area, and leave it on for about 20 to 30 minutes before washing it off with cold water and a gentle face wash.

Egg White, Cucumber, Yoghurt:

In a bowl, add one egg white, one teaspoon each of yoghurt, fresh cucumber juice and organic honey. Mix all the ingredients together until it forms a thick paste.

Apply this paste all over your face and neck area and leave it on for at least 20 minutes and then gently rinse off this face mask with lukewarm water and immediately follow it up with a gentle and nourishing moisturiser.

Egg White, Aloe Vera, Castor Oil:

To the egg white, add about a teaspoon each of aloe vera gel and castor oil and then mix all the ingredients together and apply it all over your face and neck area in a thin, even layer.

Leave it on for about 20 minutes and wash it off with a gentle face wash and some cold water. Follow it up with your favourite moisturiser.

Features

Confusion cropping up with Ne-Yo in the spotlight

Superlatives galore were used, especially on social media, to highlight R&B singer Ne-Yo’s trip to Sri Lanka: Global superstar Ne-Yo to perform live in Colombo this December; Ne-Yo concert puts Sri Lanka back on the global entertainment map; A global music sensation is coming to Sri Lanka … and there were lots more!

Superlatives galore were used, especially on social media, to highlight R&B singer Ne-Yo’s trip to Sri Lanka: Global superstar Ne-Yo to perform live in Colombo this December; Ne-Yo concert puts Sri Lanka back on the global entertainment map; A global music sensation is coming to Sri Lanka … and there were lots more!

At an official press conference, held at a five-star venue, in Colombo, it was indicated that the gathering marked a defining moment for Sri Lanka’s entertainment industry as international R&B powerhouse and three-time Grammy Award winner Ne-Yo prepares to take the stage in Colombo this December.

What’s more, the occasion was graced by the presence of Sunil Kumara Gamage, Minister of Sports & Youth Affairs of Sri Lanka, and Professor Ruwan Ranasinghe, Deputy Minister of Tourism, alongside distinguished dignitaries, sponsors, and members of the media.

According to reports, the concert had received the official endorsement of the Sri Lanka Tourism Promotion Bureau, recognising it as a flagship initiative in developing the country’s concert economy by attracting fans, and media, from all over South Asia.

However, I had that strange feeling that this concert would not become a reality, keeping in mind what happened to Nick Carter’s Colombo concert – cancelled at the very last moment.

Carter issued a video message announcing he had to return to the USA due to “unforeseen circumstances” and a “family emergency”.

Though “unforeseen circumstances” was the official reason provided by Carter and the local organisers, there was speculation that low ticket sales may also have been a factor in the cancellation.

Well, “Unforeseen Circumstances” has cropped up again!

In a brief statement, via social media, the organisers of the Ne-Yo concert said the decision was taken due to “unforeseen circumstances and factors beyond their control.”

Ne-Yo, too, subsequently made an announcement, citing “Unforeseen circumstances.”

The public has a right to know what these “unforeseen circumstances” are, and who is to be blamed – the organisers or Ne-Yo!

Ne-Yo’s management certainly need to come out with the truth.

However, those who are aware of some of the happenings in the setup here put it down to poor ticket sales, mentioning that the tickets for the concert, and a meet-and-greet event, were exorbitantly high, considering that Ne-Yo is not a current mega star.

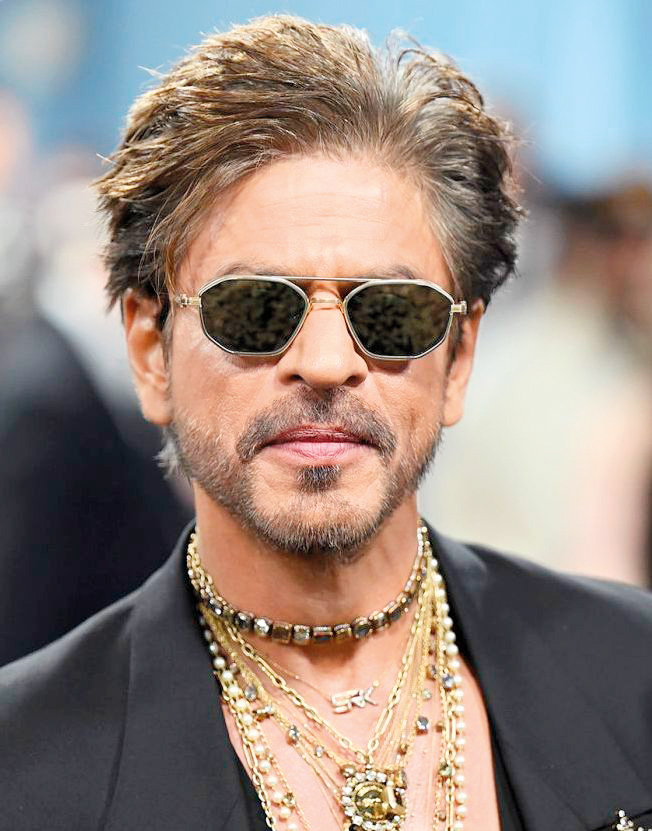

We also had a cancellation coming our way from Shah Rukh Khan, who was scheduled to visit Sri Lanka for the City of Dreams resort launch, and then this was received: “Unfortunately due to unforeseen personal reasons beyond his control, Mr. Khan is no longer able to attend.”

Referring to this kind of mess up, a leading showbiz personality said that it will only make people reluctant to buy their tickets, online.

“Tickets will go mostly at the gate and it will be very bad for the industry,” he added.

-

News7 days ago

News7 days agoStreet vendors banned from Kandy City

-

Sports4 days ago

Sports4 days agoGurusinha’s Boxing Day hundred celebrated in Melbourne

-

News2 days ago

News2 days agoLeading the Nation’s Connectivity Recovery Amid Unprecedented Challenges

-

News7 days ago

News7 days agoLankan aircrew fly daring UN Medevac in hostile conditions in Africa

-

Sports5 days ago

Sports5 days agoTime to close the Dickwella chapter

-

Features3 days ago

Features3 days agoIt’s all over for Maxi Rozairo

-

Features7 days ago

Features7 days agoRethinking post-disaster urban planning: Lessons from Peradeniya

-

Opinion7 days ago

Opinion7 days agoAre we reading the sky wrong?