Features

Gampaha 1961: Some Very Important People and Events

(Excerpted from the Memoirs of Senior DIG (Retd.) Edward Gunawardena)

With a month to go for my confirmation as an ASP, Police Headquarters thought it fit to assign me to the important police district of Gampaha. Western Province North was the SP’s Division. The office of the Supdt. of Police Western Province North was located in Gampaha. The other ASP’s districts in the Division were Peliyagoda and Negombo. The ASP Peliyagoda was T. Thalayasingham and K.V. Ramanathan was the ASP Negombo. The DIG in charge of the WP North Division was C.C. Dissanayake, DIG Range I.

The Gampaha Police district had six police stations at the time. The officers in charge were Tharmarajah, HQI Gampaha, SI P. Vedamuthu, OIC Weliweriya, SI Percy Wijesuriya, OIC Kirindiwela, IP Hamid, OIC Veyangoda, IP Alex Abeysekera, OIC Nittambuwa and IP Michael Schokman, OIC Mirigama.

Mrs. Sirima Bandaranaike was the Prime Minister and Horagolla Walawwa was located in the Nittambuwa Police Station area. This country residence of the PM was not even guarded by the police then. She did not want the field police to be hanging round at Horagolla. Whenever she visited the mansion, her security division headed by ASP Rajasooriya managed without taxing the local police. She had immense faith in her two bodyguards, IP Chandrasekera and SI Wewala. However, I did not fail to realize that the security of Horagolla was my prime responsibility. Apart from the Prime Minister, every state guest visited Horagolla, some even over nighting there.

The other politicians that mattered were the MPs with their electorates, or part of them, in the Gampaha police district. They were all cultured, honourable gentlemen with whom I could empathize with ease. There were no Provincial Councilors or Pradeshiya Sabha members at that time – the tinpot political scum of today. In that respect the sixties were wonderful years. At that time MPs had high respect for public servants; they got on excellently with each other with mutual respect for one another.

Of the MPs representing Gampaha at the time, the majority are no more. S.D. Bandaranayake and Lakshman Jayakody (LJ) are the only two living as I write this account today. The former was the MP for Gampaha and latter was the MP for Divulapitiya. The other parliamentarians were: Felix Dias Bandaranaike ( Dompe – Kirindiwela police area), Wijayabahu Wijesinghe (Mirigama), S. K. Sooriarachchi (Mahara – Weliweriya Police area) and M.P. de Z. Siriwardena (Minuwangoda). There was also JP Obeysekera (Attanagalla).

The friendly experiences I had with some of these MPs are worth recalling. The first of them I met was J.P. Obeysekera. After I had received my transfer order to Gampaha, one day I dropped in at the Fountain Cafe for lunch. I was in uniform. My father, who was the Asst. Manager there, sat at the same table and was chatting to me. Most of the senior waiters dressed in immaculate white were round my table chatting. Some of them had even carried me as a child. I still remember the names of a few of them – Cornelis with a ‘konde’ and a crescent turtle shell comb, Alphonso, Ambrose, Bhatia and Kitta. The last was the waiter who brought our meals from Fountain Cafe to St. Joseph’s College during the war years. Martin and Simon the cooks also joined the group.

As I was finishing my lunch a lean, tall man dressed in white slacks and white long sleeved shirt walked in smiling. My father greeted him warmly and guided him to a table. After he was seated, father introduced me to him. Only when I got talking to him that he realized that I was to be the new police chief of the district; and it was only then that I came to know the MP for Attanagalle. JPO was a gentleman to his finger tips. After the initial meeting at Fountain Cafe, I seldom met him. He belonged to the cream of the low-country aristocracy, was well endowed with wealth and had graduated from Cambridge. He became a friend of mine but did not want the police by his side to boost his ego. What a contrast to the politicians of later years!

After I left the Gampaha District on transfer I had the opportunity of meeting him on several occasions. Long after my retirement from the police, I wrote a novel ‘Blood and Cyanide’ published in 2001 when I was a Director of Lake House. On reading the reviews of this novel in the newspapers, JPO telephoned to congratulate me. I felt guilty about not having invited him to the book launch at the Sri Lanka Foundation Institute and I sent him a copy. He reciprocated by sending me his book on his solo flight to Ceylon from Britain after he completed his studies at Cambridge.

As I write these memoirs today S.D. Bandaranayake is alive and one of his sons, Pandu, is an MP. Before I went to Gampaha I had heard much about SD, more as a troublesome character who did not like the police very much. As he was the MP for the electorate of Gampaha I decided to make contact and took the initiative by telephoning him on a Saturday morning. He was surprised. “This is the first time a police officer has contacted me and wanted to call on me. Mr. Gunawardena, you are most welcome. My wife and I will be delighted to have you for a little dinner with us this evening”. I kept the appointment. It was quite a sumptuous dinner considering the austere times, preceded by vodka, caviar and a lively conversation. SD had many contacts in the Russian Embassy. Hence the repast!

A few days later, the Gampaha police raided an illicit liquor den in Yakkala. SD telephoned me and told me that the man under arrest was known to him and that he was not a kasippu dealer or seller. In spite of protests by the HQI Gampaha, the suspect was released by me. However, I told SD that there was good evidence against the man. Emboldened by the leniency shown by the Police this man recommenced his trade and I decided to lead a raid. It was successful. Several bottles were seized. Other than the seller, three others who were consuming illicit liquor were also arrested.

All these people together with the productions were bundled into a Land Rover and driven straight to Madugas Walawwa, SD’s residence. He was on the verandah. When I told him what happened, he was most embarrassed. He angrily walked up to the Land Rover, got his friend to alight, gave him two thundering slaps and told him to stop this business forthwith. The gentleman he was, SD did not hold this against me.

Lakshman Jayakody (LJ) was a well to do proprietary coconut planter and a full blooded Trinitian. A large part of his electorate fell within the Mirigama Police area of which the OIC was Michael Schokman. Jayakody and Schokman had both played cricket for Trinity, the latter the senior of the two. They got on very well and as a result the ASP Gampaha had very few problems from the Mirigama Police area!

Lakshman J being a descendant of John de Silva was a lover of the Tower Hall Sinhala Music. He himself was fond of singing these famous old songs. One day in 1961 he invited me to a musical evening with an exclusive audience, mainly from the diplomatic corps. It was held at the Tower Hall and lasted for about three hours. Some of the singers were H.W. Rupasinghe, Eddie Master, Allen Ratnayake, A.M.U. Raj, Latiff Bhai and G.S.B. Rani. The only instruments were the tabla, serapina (harmonium) and the violin. The violinist was W.D. Albert Perera who later changed his name to W.D. Amaradeva.

Lakshman Jayakody and I have remained friends ever since. In the 70s when I was the Director Planning and Research and P.A. to the IGP, I had occasion to work with him closely particularly during the JVP uprising of 1971. When two Cessna light aircraft were acquired by the SLAF at that time, it was he and I who travelled in the inaugural flight to Palaly. Apart from Palaly, where we were entertained to lunch by Col. Bull Weeratunga, we visited the Karainagar Naval base which was in charge of Commander Neville Andrado. Lakshman J. was the Junior Minister of Defence at that time.

Felix Dias Bandaranaike was a friendly sort when I first met him in 1961. He was the MP for Dompe and the Kirindiwela police station came within the Gampaha police district with SI Percy Wijesuriya in charge. Whenever FDB visited his electorate he functioned from the Weke Walawwa which was in the Kirindiwela police area. I still remember the day he wanted me to stay for lunch with him. He had got the caretaker to prepare his favourites, jak curry and a dry fish bedun which I too enjoyed. A heavy smoker, FDB smoked a pipe and cigarettes. At the end of the meal, he was looking for a cigarette as he had finished all he had brought. Accepting a Bristol cigarette from me he joked, “no harm sharking a punt from a Peradeniya junior.” Perhaps the Peradeniya connection helped us to get on well.

With FDB’s meteoric rise to dizzy heights in the political firmament, lesser mortals like me quite naturally faded away from his reckoning. However, I consider it my good fortune to have known him well even fleetingly. He indeed has a unique place in Sri Lanka’s history. It was he by his courageous and decisive conduct that saved the nation when democracy was in peril in 1962 and 1971.

Wijebahu Wijesinghe and S.K.K. Sooriarachchi were also easy to get on with. The former once visited the United States on an official visit with fellow MPs Wijepala Mendis and I.A. Cader. As they were to visit Texas A and M, I made arrangements for them to stay with my brother, Irwin, who was doing his Master’s degree there.

M.P. de Z Siriwardena, the MP for Minuwangoda was the Deputy Minister of Labour. Very much unlike the other MPs of the Gampaha district, he was abrasive in his ways and often rubbed the police on the wrong side. I soon realized that he was a man who could easily be outwitted. His main support group in the electorate was the large scale illicit distillers and he was determined to protect them from police action. He even encouraged them to resist and obstruct police raids.

Once a police party from Gampaha led by IP Buhary was obstructed. Buhary, acting in self defence, had used a police baton on a violent thug. This man had died of head injuries and a magisterial inquiry was in progress. One morning when I was in the HQI’s office M.P. de Z S walked in with a few others saying, “I say ASP, your people have killed my man.” I told him to sit down and requested the HQI to send for the Information Book. I calmly told the MP that as he appeared to know something about the death, that he is at liberty to make a statement. He got cold feet and left saying that he did not want to make a statement. Politicians are big talkers but discreetly avoid situations that make them witnesses in court cases. They shun cross-examination.

I remember, not long after, a strong supporter of the MP made a complaint against the police of assault. The complaint, made to the SP Jayakody, alleged that an Inspector had even spoken disparagingly of the MP. As my SP showed interest in this complaint, I fixed an early date for the preliminary inquiry in my office and notified the witnesses. Two days before the inquiry this MP had telephoned the SP and told him that the inquiry should be held in a school at Asgiriya. I told the SP that in that case it will take the form of a public inquiry. “Gune, do whatever you want”, was his response.

I told HQI Tharmarajah to arrange a school and fixed the date for the inquiry. I also told him that at the request of the MP this will be a public inquiry and told him to arrange for a few people to come forward and volunteer evidence favourable to the police. Tharmarajah, the seasoned policeman, was amazed at the suggestion. After recording the statements of the formal witnesses I announced that any person who wished to give evidence could do so. Three out of many who came forward were selected. Their evidence (well coached by the police) was most convincing. My SP had no alternative but to agree with my findings. M.P. de Z S certainly went through a learning exercise. Distraught and defeated he had told my SP, “your ASP is a hard nut.”

Funeral of Singho Mahattaya alias Wickramarachchi of Attanagalla

One morning IP Alex Abeysekera, the OIC Nittambuwa telephoned me that Singho Mahattaya of Attanagalle had died; and the Governor -General and Prime Minister were due to pay their respects at his residence. I had never heard of Singho Mahattaya and told the Nittambuwa OIC to have some police presence at the residence and also along the route. On second thoughts I asked Tharmarajah the HQI Gampaha about the deceased. He told me that it was this man, who was rich and influential, who had always been the proposer of the name of S.W.R.D. Bandaranaike at elections.

After the discussion I had with Tharmarajah I decided to visit the sprawling residence of Singho Mahattaya at Maligatenne. OIC Nittambuwa was there and he introduced me to Singho Mahattaya’s two sons, Nagasiri and Kithsiri who warmly received me. Prime Minister Sirima Bandaranaike had already visited the funeral house once with her children and was expected to visit again. Nagasiri and Kithsiri were awaiting the arrival of Sir Oliver Goonatilleke, the Governor-General. When he arrived in his Austin Princess I saluted him and received him. I was the most senior public official present.

Having introduced the two sons, I accompanied him into the house and remained close to him. Soon I realized that he was comfortable with me by his side. Before leaving the funeral house the G.G. whispered to me that he would like to visit the Bandaranaike Samadhi that was being constructed at the time. I conveyed this information to the HQI and went ahead of Sir Oliver, having instructed the pilot officer to stop behind my car that will be parked on the road opposite the Samadhi site.

Although my intention was to take him to the site by car, he preferred to walk. The G.G. was received at the site by the most senior officer of the Public Works Dept. who was present, Peter Jayawardena. Peter explained the difficulties to meet the completion target of September 26, 1961. Sir Oliver saw for himself how the work was going on day and night. There were several temporary tea kiosks that had come up on the roadside to cater to the workers. He walked with me to all these places and told the boutique keepers that they should unfailingly supply the workforce with their requirements. Before getting into his car he told me to get these kades to supply whatever the workers want and send the bill to Queen’s House! A tall order indeed from a man who had even been the country’s Auditor-General. I passed this information to Peter Jayawardena. That’s all I could have done.

During my meeting with Sir Oliver at this funeral he even addressed me as ‘Sonny’. Showing great interest, he asked me about crime in the area and troublesome characters. He asked me about the MPs and the relations I maintained with them, specially asking me whether they interfere in my work. He was also keen to know about the popularity of each of them in their respective electorates. The significance of this conversation with Sir Oliver dawned on me only after the attempted coup d’etat which took place a few months later.

Singho Mahattaya had been a great admirer of SWRD Bandaranaike. Because SWRD had gray hounds, he (Singho Mahattaya) had also thought of bringing up dogs. He had imported a pair of Great Danes and named them Barnes and Barney. Barnes Ratwatte was the father of Sirimavo! Nagasiri, the elder son of SM who became very friendly with me, gifted me with a full grown Great Dane that had shown affection to me whenever I visited him. However, after about eight months I had to put him down because he became fierce and even growled at me. Nagasiri was a great friend indeed. Whenever I visited him he treated me with the best of food and drink. He died young. I remember attending his funeral at Attanagalle with Stanley Senanayake, the IGP, who also had known Singho Mahattaya and his family.

Features

RIDDHI-MA:

A new Era of Dance in Sri Lanka

Kapila Palihawadana, an internationally renowned dancer and choreographer staged his new dance production, Riddhi-Ma, on 28 March 2025 at the Elphinstone theatre, which was filled with Sri Lankan theatregoers, foreign diplomats and students of dance. Kapila appeared on stage with his charismatic persona signifying the performance to be unravelled on stage. I was anxiously waiting to see nATANDA dancers. He briefly introduced the narrative and the thematic background to the production to be witnessed. According to him, Kapila has been inspired by the Sri Lankan southern traditional dance (Low Country) and the mythologies related to Riddhi Yâgaya (Riddi Ritual) and the black magic to produce a ‘contemporary ballet’.

Riddhi Yâgaya also known as Rata Yakuma is one of the elaborative exorcism rituals performed in the southern dance tradition in Sri Lanka. It is particularly performed in Matara and Bentara areas where this ritual is performed in order to curb the barrenness and the expectation of fertility for young women (Fargnoli & Seneviratne 2021). Kapila’s contemporary ballet production had intermingled both character, Riddi Bisaw (Princes Riddhi) and the story of Kalu Kumaraya (Black Prince), who possesses young women and caught in the evil gaze (yaksa disti) while cursing upon them to be ill (De Munck, 1990).

Kapila weaves a tapestry of ritual dance elements with the ballet movements to create visually stunning images on stage. Over one and a half hours of duration, Kapila’s dancers mesmerized the audience through their virtuosic bodily competencies in Western ballet, Sri Lankan dance, especially the symbolic elements of low country dance and the spontaneity of movements. It is human bodily virtuosity and the rhythmic structures, which galvanised our senses throughout the performance. From very low phases of bodily movements to high speed acceleration, Kapila managed to visualise the human body as an elevated sublimity.

Contemporary Ballet

Figure 2 – (L) Umesha Kapilarathna performs en pointe, and (R) Narmada Nekethani performs with Jeewaka Randeepa, Riddhi-Ma, at Elphinstone Theatre, Maradana, 28th March 2025. Source:

Malshan Witharana

The dance production Riddhi-Ma was choreographed in several segments accompanied by a flow of various music arrangements and sound elements within which the dance narrative was laid through. In other words, Kapila as a choreographer, overcomes the modernist deadlock in his contemporary dance work that the majority of Sri Lankan dance choreographers have very often succumbed to. These images of bodies of female dancers commensurate the narrative of women’s fate and her vulnerability in being possessed by the Black Demon and how she overcomes and emancipates from the oppression. In this sense, Kapila’s dancers have showcased their ability to use the bodies not much as an object which is trained to perform a particular tradition but to present bodily fluidity which can be transformed into any form. Kapila’s performers possess formlessness, fluid fragility through which they break and overcome their bodily regimentations.

It was such a highly sophisticated ‘contemporary ballet’ performed at a Sri Lankan theatre with utmost rigour and precision. Bodies of all male and female dancers were highly trained and refined through classical ballet and contemporary dance. In addition, they demonstrated their abilities in performing other forms of dance. Their bodies were trained to achieve skilful execution of complex ballet movements, especially key elements of traditional ballet namely, improvisation, partnering, interpretation and off-balance and the local dance repertoires. Yet, these key ballet elements are not necessarily a part of contemporary ballet training (Marttinen, 2016). However, it is important for the dance students to learn these key elements of traditional ballet and use them in the contemporary dance settings. In this sense, Kapila’s dancers have achieved such vigour and somatic precision through assiduous practice of the body to create the magic on stage.

Pas de deux

Among others, a particular dance sequence attracted my attention the most. In the traditional ballet lexicon, it is a ‘pas de deux’ which is performed by the ‘same race male and female dancers,’ which can be called ‘a duet’. As Lutts argues, ‘Many contemporary choreographers are challenging social structures and norms within ballet by messing with the structure of the pas de deux (Lutts, 2019). Pas de Deux is a dance typically done by male and female dancers. In this case, Kapila has selected a male and a female dancer whose gender hierarchies appeared to be diminished through the choreographic work. In the traditional pas de deux, the male appears as the backdrop of the female dancer or the main anchorage of the female body, where the female body is presented with the support of the male body. Kapila has consciously been able to change this hierarchical division between the traditional ballet and the contemporary dance by presenting the female dominance in the act of dance.

The sequence was choreographed around a powerful depiction of the possession of the Gara Yakâ over a young woman, whose vulnerability and the powerful resurrection from the possession was performed by two young dancers. The female dancer, a ballerina, was in a leotard and a tight while wearing a pair of pointe shoes (toe shoes). Pointe shoes help the dancers to swirl on one spot (fouettés), on the pointed toes of one leg, which is the indication of the ballet dancer’s ability to perform en pointe (The Kennedy Centre 2020).

The stunning imagery was created throughout this sequence by the female and the male dancers intertwining their flexible bodies upon each other, throwing their bodies vertically and horizontally while maintaining balance and imbalance together. The ballerina’s right leg is bent and her toes are directed towards the floor while performing the en pointe with her ankle. Throughout the sequence she holds the Gara Yakâ mask while performing with the partner.

The male dancer behind the ballerina maintains a posture while depicting low country hand gestures combining and blurring the boundaries between Sri Lankan dance and the Western ballet (see figure 3). In this sequence, the male dancer maintains the balance of the body while lifting the female dancer’s body in the air signifying some classical elements of ballet.

Haptic sense

Figure 3: Narmada Nekathani performs with the Gara Yaka mask while indicating her right leg as en pointe. Male dancer, Jeewaka Randeepa’s hand gestures signify the low country pose. Riddhi-Ma, Dance Theatre at Elphinstone Theatre, 28th March 2025. Source: Malshan Witharana.

One significant element of this contemporary ballet production is the costume design. The selection of colour palette, containing black, red and while combining with other corresponding colours and also the costumes which break the traditional rules and norms are compelling. I have discussed in a recent publication how clothes connect with the performer’s body and operate as an embodied haptic perception to connect with the spectators (Liyanage, 2025). In this production, the costumes operate in two different ways: First it signifies sculpted bodies creating an embodied, empathic experience.

Secondly, designs of costumes work as a mode of three dimensional haptic sense. Kapila gives his dancers fully covered clothing, while they generate classical ballet and Sinhalese ritual dance movements. The covered bodies create another dimension to clothing over bodies. In doing so, Kapila attempts to create sculpted bodies on stage by blurring the boundaries of gender oriented clothing and its usage in Sri Lankan dance.

Sri Lankan female body on stage, particularly in dance has been presented as an object of male desire. I have elsewhere cited that the lâsya or the feminine gestures of the dance repertoire has been the marker of the quality of dance against the tândava tradition (Liyanage, 2025). The theatregoers visit the theatre to appreciate the lâsya bodies of female dancers and if the dancer meets this threshold, then she becomes the versatile dancer. Kandyan dancers such as Vajira and Chithrasena’s dance works are explored and analysed with this lâsya and tândava criteria. Vajira for instance becomes the icon of the lâsya in the Kandyan tradition. It is not my intention here to further discuss the discourse of lâsya and tândava here.

But Kapila’s contemporary ballet overcomes this duality of male-female aesthetic categorization of lâsya and tândava which has been a historical categorization of dance bodies in Sri Lanka (Sanjeewa 2021).

Figure 4: Riddhi-Ma’s costumes creates sculpted bodies combining the performer and the audience through empathic projection. Dancers, Sithija Sithimina and Senuri Nimsara appear in Riddhi-Ma, at Elphinstone Theatre, 28th March 2025, Source, Malshan Witharana.

Conclusion

Dance imagination in the Sri Lankan creative industry exploits the female body as an object. The colonial mind set of the dance body as a histrionic, gendered, exotic and aesthetic object is still embedded in the majority of dance productions produced in the current cultural industry. Moreover, dance is still understood as a ‘language’ similar to music where the narratives are shared in symbolic movements. Yet, Kapila has shown us that dance exists beyond language or lingual structures where it creates humans to experience alternative existence and expression. In this sense, dance is intrinsically a mode of ‘being’, a kinaesthetic connection where its phenomenality operates beyond the rationality of our daily life.

At this juncture, Kapila and his dance ensemble have marked a significant milestone by eradicating the archetypical and stereotypes in Sri Lankan dance. Kapila’s intervention with Riddi Ma is way ahead of our contemporary reality of Sri Lankan dance which will undoubtedly lead to a new era of dance theatre in Sri Lanka.

References

De Munck, V. C. (1990). Choosing metaphor. A case study of Sri Lankan exorcism. Anthropos, 317-328. Fargnoli, A., & Seneviratne, D. (2021). Exploring Rata Yakuma: Weaving dance/movement therapy and a

Sri Lankan healing ritual. Creative Arts in Education and Therapy (CAET), 230-244.

Liyanage, S. 2025. “Arts and Culture in the Post-War Sri Lanka: Body as Protest in Post-Political Aragalaya (Porattam).” In Reflections on the Continuing Crises of Post-War Sri Lanka, edited by Gamini Keerawella and Amal Jayawardane, 245–78. Colombo: Institute for International Studies (IIS) Sri Lanka.

Lutts, A. (2019). Storytelling in Contemporary Ballet.

Samarasinghe, S. G. (1977). A Methodology for the Collection of the Sinhala Ritual. Asian Folklore Studies, 105-130.

Sanjeewa, W. (2021). Historical Perspective of Gender Typed Participation in the Performing Arts in Sri Lanka During the Pre-Colonial, The Colonial Era, and the Post-Colonial Eras. International Journal of Social Science And Human Research, 4(5), 989-997.

The Kennedy Centre. 2020. “Pointe Shoes Dancing on the Tips of the Toes.” Kennedy-Center.org. 2020 https://www.kennedy-center.org/education/resources-for-educators/classroom-resources/media- and-interactives/media/dance/pointe-shoes/..

Acknowledgements

The author wishes to thank Himansi Dehigama for proofreading this article.

About the author:

Saumya Liyanage (PhD) is a film and theatre actor and professor in drama and theatre, currently working at the Department of Theatre Ballet and Modern Dance, Faculty of Dance and Drama, University of the Visual and Performing Arts (UVPA), Colombo. He is the former Dean of the Faculty of Graduate Studies and is currently holding the director position of the Social Reconciliation Centre, UVPA Colombo.

Features

Sri Lanka’s Foreign Policy amid Geopolitical Transformations: 1990-2024 – Part II

Chinese Naval Entry and End of Post-War Unipolarity

The ascendancy of China as an emerging superpower is one of the most striking shifts in the global distribution of economic and political power in the 21st century. With its strategic rise, China has assumed a more proactive diplomatic and economic role in the Indian Ocean, signalling its emergence as a global superpower. This new leadership role is exemplified by initiatives such as the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) and the establishment of the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB). The Economist noted that “China’s decision to fund a new multilateral bank rather than give more to existing ones reflects its exasperation with the glacial pace of global economic governance reform” (The Economist, 11 November 2014). Thus far, China’s ascent to global superpower status has been largely peaceful.

In 2025, in terms of Navy fleet strength, China became the world’s largest Navy, with a fleet of 754 ships, thanks to its ambitious naval modernisation programme. In May 2024, the People’s Liberation Army Navy (PLAN) further strengthened its capabilities by commissioning the Fujian, its latest aircraft carrier. Equipped with an advanced electromagnetic catapult system, the Fujian can launch larger and heavier aircraft, marking a significant upgrade over its predecessors.

Driven by export-led growth, China sought to reinvest its trade surplus, redefining the Indian Ocean region not just as a market but as a key hub for infrastructure investment. Notably, over 80 percent of China’s oil imports from the Persian Gulf transit to the Straits of Malacca before reaching its industrial centres. These factors underscore the Indian Ocean’s critical role in China’s economic and naval strategic trajectories.

China’s port construction projects along the Indian Ocean littoral, often associated with the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), exemplify its deepening geopolitical and economic engagement in the region. These initiatives encompass multipurpose berth development, deep-sea port construction, and supporting infrastructure projects aimed at enhancing maritime connectivity and trade. Key projects include the development of Gwadar Port in Pakistan, a strategic asset for China’s access to the Arabian Sea; Hambantota Port in Sri Lanka, which became a focal point of debt diplomacy concerns; the Payra deep-sea port in Bangladesh; as well as port and road infrastructure development in Myanmar’s Yunnan and Kyaukphyu regions and Cambodia’s Koh Kong.

While these projects were promoted as avenues for economic growth and regional connectivity, they also triggered geopolitical tensions and domestic opposition in several host countries. Concerns over excessive debt burdens, lack of transparency, and potential dual-use (civilian and military) implications of port facilities led to scrutiny from both local and external stakeholders, including India and Western powers. As a result, some projects faced significant pushback, delays, and, in certain cases, suspension or cancellation. This opposition underscores the complex interplay between economic cooperation, strategic interests, and sovereignty concerns in China’s Indian Ocean engagements.

China’s expanding economic, diplomatic, and naval footprint in the Indian Ocean has fundamentally altered the region’s strategic landscape, signalling the end of early post-Cold War unipolarity. Through the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) initiatives, China has entrenched itself economically, financing. Diplomatically, Beijing has deepened its engagement with littoral states through bilateral agreements, security partnerships, and regional forums, challenging traditional Western and Indian influence.

China’s expanding naval deployments in the Indian Ocean, including its military base in Djibouti, and growing security cooperation with regional states, mark the end of unchallenged US dominance in the region. The Indian Ocean is now a contested space, where China’s presence compels strategic recalibrations by India, the United States, and other regional actors. The evolving security landscape in the Indian Ocean—marked by intensifying competition, shifting alliances, and the rise of a multipolar order—has significant implications for Sri Lanka’s geopolitical future.

India views China’s growing economic, political, and strategic presence in the Indian Ocean region as a key strategic challenge. In response, India has pursued a range of strategic, political, and economic measures to counterbalance Chinese influence, particularly in countries like Sri Lanka through infrastructure investment, defense partnerships, and diplomatic engagements.

Other Extra-Regional powers

Japan and Australia have emerged as significant players in the post-Cold War strategic landscape of the Indian Ocean. During the early phases of the Cold War, Australia played a crucial role in Western ‘Collective Security Alliances’ (ANZUS and (SEATO). However, its direct engagement in Indian Ocean security remained limited, primarily supporting the British Royal Navy under Commonwealth obligations. Japan, meanwhile, refrained from deploying naval forces in the region after World War II, adhering to its pacifist constitution and post-war security policies. In recent decades, shifting strategic conditions have prompted both Japan and Australia to reassess their roles in the Indian Ocean, leading to greater defence cooperation and a more proactive regional presence.

In the post-Cold War era, Australia has progressively expanded its naval engagements in the Indian Ocean, driven by concerns over maritime security, protection of trade routes, and China’s growing influence. Through initiatives, such as the Quadrilateral Security Dialogue (Quad) and deeper defence partnerships with India and the United States, Australia has bolstered its strategic presence in the Indian Ocean region.

Recalibration of Japan’s approach

Japan, too, has recalibrated its approach to Indian Ocean security in response to geopolitical shifts. Recognising the Indian Ocean’s critical importance for its energy security and trade, Japan has strengthened its naval presence through port visits, joint exercises, and maritime security cooperation. The Japan Maritime Self-Defence Force (JMSDF) has taken on a more active role in anti-piracy operations, freedom of navigation operations (FONOPS), and strategic partnerships with Indian Ocean littoral states. This shift aligns with Japan’s broader strategy of contributing to regional stability while balancing its constitutional constraints on military force projection.

Japan’s proactive role in the Indian Ocean region is evident in its diplomatic and defence engagements. In January 2019, Japan sent its Foreign Minister, Taro Kono, and Chief of Staff, Joint Staff, Katsutoshi Kawano, to the Raisina Dialogue, a high-profile geopolitical conference in India. Japan’s National Security Strategy, released in December 2022, identifies China’s growing assertiveness as its greatest strategic challenge and underscores the need to deepen bilateral ties and multilateral defence cooperation in the Indian Ocean. It also emphasises the importance of securing stable access to sea-lanes, through which more than 80 percent of Japan’s oil imports pass. In recent years, Japan has expanded its port investment portfolio across the Indian Ocean, with major projects in Sri Lanka, Bangladesh, and Myanmar. In 2021, Japan participated for the first time in CARAT-Sri Lanka (Cooperation Afloat Readiness and Training), a bilateral naval exercise. Japan’s Maritime Self-Defence Force returned for the exercise in January 2023, held at Trincomalee Port and Mullikulam Base.

Japan’s strategic interests in the Indian Ocean have been most evident in its involvement in port infrastructure development projects. Sri Lanka, Bangladesh, and Myanmar are key countries where early Chinese-led port construction faced setbacks. Unlike India, which carries historical and political complexities in its relations with these countries, Japan is better positioned to compete with China. In December 2021, a Japanese company established a ship repair and rebuilding facility in Trincomalee, complementing the already well-established Tokyo Cement factory. When the Sri Lanka Ports Authority announced plans in mid-2022 to develop Trincomalee as an industrial port—inviting expressions of interest from investors to utilise port facilities and up to 2,400 hectares of surrounding land—Trincomalee regained strategic attention.

The Colombo Dockyard, in collaboration with Japan’s Onomichi Dockyard, has established a rapid response afloat service in Trincomalee, marking a significant development in Japan’s engagement with Sri Lanka’s maritime infrastructure. This initiative aligns with Japan’s broader strategic interests in the Bay of Bengal, a region of critical economic and security importance. A key Japanese concern appears to be limiting China’s ability to establish a permanent presence in Trincomalee. This initiative underscores the broader strategic competition in the Indian Ocean. Trincomalee, with its deep-water harbour, has long been regarded as a critical maritime asset. Japan’s involvement reflects its efforts to deepen economic and strategic engagement with Sri Lanka amid growing regional competition. The challenge before Sri Lanka is how to navigate this strategic contest while maximising its national interests.

Other Regional Powers

In analyzing the evolving naval security architecture of the post-Cold War Indian Ocean, particular attention should be given to the naval developments of regional powers such as Pakistan, Indonesia, and Malaysia. In 2012, Pakistan established the Naval Strategic Force Command (NSFC) to strengthen Pakistan’s policy of Credible Minimum Deterrence (CMD). The creation of the NSFC suggests a shift toward sea-based deterrence, complementing Pakistan’s broader military strategy. In December 2012, Pakistan conducted a series of cruise missile tests from naval platforms in the Arabian Sea. Given India’s expanding maritime capabilities, which Pakistan views as a significant threat, the Pakistan Navy may consider deploying tactical nuclear weapons on surface ships as part of its evolving deterrence strategy. Sri Lanka’s foreign policy cannot overlook this development.

Indonesia also emerged as a significant player in the evolving naval security landscape of the Indian Ocean. In 2010, it launched a military modernisation programme aimed at achieving a ‘Minimum Essential Force’ (MEF) by 2024. As part of this initiative, Indonesia sought to build a modern Navy with 247 surface vessels and 12 submarines. One of the primary challenges faced by the Indonesian Navy (TNI-AL) is piracy. To enhance maritime security, Indonesia and Singapore signed the SURPIC Cooperation Arrangement in Bantam in May 2005, enabling real-time sea surveillance in the Singapore Strait for more effective naval patrols. In 2017, Indonesia introduced the Indonesian Ocean Policy (IOP) and subsequently incorporated blue economy strategies into its national development agenda, reinforcing its maritime vision. According to projections from the Global Firepower Index, published in 2025, the Indonesian Navy is ranked fourth in global ranking and second in Asia in terms of Navy fleet strength (Global Firepower, 2025).

In October 2012, the Royal Malaysian Navy (RMN) announced plans to build a second Scorpène simulator training facility at its base in Kota Kinabalu, in addition to submarine base in Sepanggar, Sabah, constructed in 2002. To enhance its naval capabilities, the RMN planned to procure 18 Littoral Mission Ships (LMS) for maritime surveillance and six Littoral Combat Ships (LCS) between 2019 and 2023. Malaysia and China finalised their first major defence deal during Prime Minister Najib Razak’s visit to Beijing in November 2016. During this visit, Malaysia’s Defence Ministry signed a contract to procure LMS from China, as reported by The Guardian. Despite this agreement, Malaysia continues to maintain amicable relations with both China and India, as does Indonesia.

The increasing presence of major naval powers, the rise of regional stakeholders, and the growing significance of trade routes and maritime security have transformed the Indian Ocean into a central pivot of both regional and global politics, with Sri Lanka positioned at its heart. (To be Continued)

by Gamini Keerawella

Features

More excitement for Andrea Marr…

Sri Lankan Andrea Marr, now based in Australia, is in the spotlight again. She says she has teamed up with a fantastic bunch of Sri Lankan musicians, in Melbourne, and the band is called IntoGroove.

“The band has been going strong for many years and I have been a fan of this outfit for quite a few years; just love these guys, authentic R&B and funk.”

Although Andrea has her original blues band, The McNaMarr Project, and they do have a busy schedule, she went on to say that “when the opportunity came up to join these guys, I simply couldn’t refuse … they are too good.”

IntoGroove is Jude Nicholas (lead vocals), Peter Menezes (bass), Keith Pereira (drums), Blaise De Silva (keyboards) and and Steve Wright (guitar).

Andrea Marr: Powerhouse of the blues

“These guys are a fantastic band and I really want everyone to hear them.”

Andrea is a very talented artiste with many achievements to her credit, and a vocal coach, as well.

In fact, she did her second vocal coaching session at Australian Songwriters Conference early this year.

Her first student showcase for this year took place last Sunday, in Melbourne, and it brought into the spotlight the wonderful acts she has moulded, as teacher and mentor.

What makes Andrea extra special is that she has years of teaching experience and is able to do group vocal coaching for all styles, levels and genres.

In January, this year, she performed at the exclusive ‘Women In Blues’ showcase at Alfred’s On Beale Street (rock venue with live entertainment), in Memphis, in the USA, during the International Blues Challenge when bands from all over the world converge on Memphis for the ‘Olympics of the Blues.’

The McNaMarr Project with Andrea and Lindsay Marr in the

vocal spotlight

This was her fourth performance in the home of the blues; she has represented Australian Blues three times and, on this occasion, she went as ambassador for Blues Music Victoria, and The Melbourne Blues Appreciation Society’s ‘Women In Blues’ Coordinator.

Andrea was inducted into the Blues Music Victoria Hall of Fame in 2022 and released her 10th album which hit #1 on the Australian Blues Charts.

Known as ‘the pint-sized powerhouse of the blues’ for her high energy, soulful, original music, Andrea is also a huge fan of the late Elvis Presley and has checked out Graceland, in Memphis, Tennessee, USA, many times.

In Melbourne, the singer also plays a major role in helping Animal Rescue organisations find homes for abandoned cats.

Andrea Marr’s wish, at the moment, is that the Lankan audience, in Melbourne, would get behind this band, IntoGroove. They are world class, she added.

-

Business2 days ago

Business2 days agoColombo Coffee wins coveted management awards

-

Features3 days ago

Features3 days agoStarlink in the Global South

-

Business4 days ago

Business4 days agoDaraz Sri Lanka ushers in the New Year with 4.4 Avurudu Wasi Pro Max – Sri Lanka’s biggest online Avurudu sale

-

Business5 days ago

Business5 days agoStrengthening SDG integration into provincial planning and development process

-

Business4 days ago

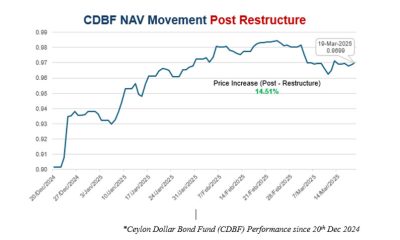

Business4 days agoNew SL Sovereign Bonds win foreign investor confidence

-

Sports6 days ago

Sports6 days agoTo play or not to play is Richmond’s decision

-

Features3 days ago

Features3 days agoModi’s Sri Lanka Sojourn

-

Sports5 days ago

Sports5 days agoNew Zealand under 85kg rugby team set for historic tour of Sri Lanka