Opinion

Full implementation of 13A: Final solution to ‘national problem’ or end of unitary state? – Part IV

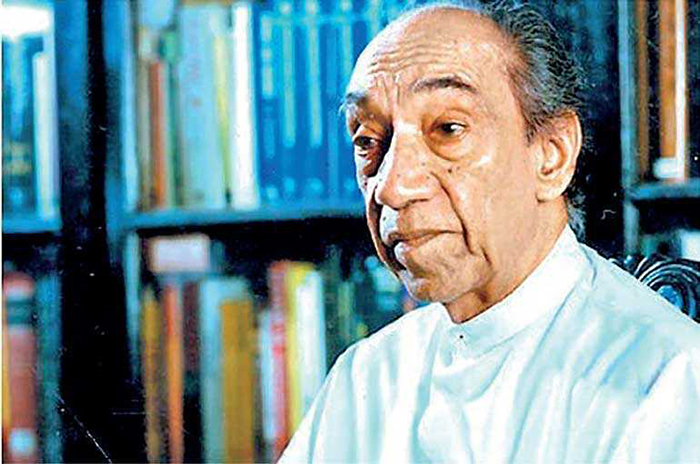

By Kalyananda Tiranagama

Executive Director

Lawyers for Human Rights and Development

(Part III of this article appeared in The Island yesterday (28 Sept. 2023)

President Jayewardene stands up against Ranil Wickremesinghe

President J. R. Jayewardene, on the occasion of the Opening of Parliament on 20 Feb., 1986 said: ‘‘Permit me to speak on the government’s attempts since 1977 to seek a political solution to the problems arising in the Northern and Eastern Provinces.

‘‘Our first attempt to do so was outlined in the UNP Election Manifesto of 1977. These proposals were prepared in consultation with some of the TULF MPs at that time. I have in my Address to Hon. Members on 23rd February 1984 outlined the steps taken to implement them as follows:

‘‘Since 1977 the government has made Tamil a National Language in the Constitution; amended rules governing entrance to universities and removed any racial bias governing those rules; removed the regulations prescribing racial considerations governing entry to the Public Services and promotion in the services.

‘‘District Councils have been created and District Ministers appointed. The TULF accepted them and worked for them for two years and contested elections. Last year they withdrew from them as sufficient powers and finance had not been allotted to them.

‘‘The search for a political solution was the profound concern of the government of SL. It was this commitment to reach a peaceful solution to the problem that led SL to take the unprecedented step on the part of any Sovereign State of sending her accredited representatives to explore the possibility of reaching a settlement at two Conferences held in Thimpu, Bhutan in August 1985 … arranged with the Tamil groups through the good offices of India.

‘‘However, neither the TULF nor the groups who attended these talks showed any serious inclination to discuss any of the proposals placed before them by the Govt. of SL. Their final response was an outright rejection of the government proposals and an invitation to the Govt. of SL to make new proposals that would accord with the so-called cardinal principles which they enunciated, which were no more than a re-statement of the demand for Eelam.

‘‘On 12th July 1985 the 6 Tamil groups made a statement of the ‘Four Principles’ on which they were working. On 13th August 1985 the leader of the SL Delegation, Dr. H.W. Jayewardene responded to it with a statement on the ‘Four Principles’ mentioned by the Tamil groups.

‘‘He dealt with the (i) recognition of the Tamils as a distinct nationality, (ii) a separate homeland and (iii) self-determination for the Tamils; and (iv) the linkage of the Northern and Eastern Provinces as a reaffirmation of the demand for a separate state and could not be the subject of discussion and acceptance by the SL govt.

‘‘The SL delegation also submitted an outline of the structure of the sub-national units of a Participatory System of Governance on 16th August, but this too was not considered by the Tamil groups though it indicated areas on which discussion and agreement were possible.

‘‘The Accord reached in Thimpu and New Delhi were to be the basis of any future discussions. Such discussion would not reopen the Four Principles mentioned earlier in any form whatsoever. This was the basis of the understanding of both the Govts of India and Sri Lanka ….

” There are certain principles which we cannot depart from arriving at a solution. We cannot barter away the unity of Sri Lanka, its democratic institutions, the right of every citizen in this country whatever his race, religion, or caste to consider the whole Island as his Homeland, enjoying equal rights, constitutionally, politically, socially, in education and employment are equally inviolable.”

“At present the Sri Lanka Tamils are in a minority in the Eastern Province while the Sinhalese and the Muslims together constitute nearly sixty per cent of the population. Since the Sri Lanka Tamils constitute more than ninety per cent of the population in the Northern Province, the object of the amalgamation of the North and the East is clear – the Sri Lanka Tamils will after amalgamation become the majority group in the combined unit of administration. Once the amalgamation is achieved the concept of the traditional homeland of the Tamils which has been a corner-stone of agitation in the post-independence period will be revived as this is the only ground on which the T.U.L.F.

denies the legitimate rights of the Sinhala people to become settlers in the Northern and Eastern provinces. Nor does the traditional homelands theory recognise any rights for the Muslims either except as an attenuated minority in the amalgamated territory. So, on the one hand while professing to urge the case for all Tamil speaking people in fact the T.U.L.F. is covertly seeking to secure the extensive areas for development, especially under the accelerated Mahaweli Program, for exploitation by the Sri Lankan Tamils alone. This in short is the duplicitous motivation behind the demand for amalgamation.

‘’ Quite candidly, the Sinhala people do not regard the demand for the amalgamation of the Northern and Eastern Provinces as a bona fide claim but as one motivated by an ulterior purpose, namely, as a first step towards the creation of a separate state comprising these two Provinces. The recent outrages by Tamil terrorists against the Sinhala civilian population settled in the North and East killing vast numbers of them, ravaging their homesteads and making thousands of them refugees in their own land has only made their apprehensions seem more real than ever before.

” Even the most naive of people could not expect a single Sinhalese to go back to the North and/or East if the maintenance of law and order within those areas becomes the exclusive preserve of the political leaders and patrons of the very terrorists who chased them out. Could one for instance expect the survivors of Namalwatta to go back to their village if the leader of the Tamil Terrorist gang that murdered their families is the A S.P. of the area? Not only would those poor refugees not go back but those Sinhalese, including those in Ampara and Trincomalee, who are still living in the North and East, would necessarily leave their lands and flee to the South, if these proposals are implemented.”

” These proposals are totally unacceptable. If they are implemented, the T. U. L. F. would have all but attained Eelam. It need hardly be said that even if the demand for a Tamil Linguistic State is granted, further problems and conflicts are bound to arise between that Tamil Linguistic State of the North and East and the Centre. Water, hydropower and the apportioning of funds are some of the areas in which conflicts could arise. A cause or pretext for a conflict on which to base a unilateral declaration of independence could easily be found.

There can be little doubt that what T.U.L.F. seeks to achieve by its demands is the necessary infrastructure for a State of Eelam, after which a final putsch could be made for the creation of a State of Eelam, comprising not only of the North and East, but of at least the hill country and the NCP as well.” (quoted in the Judgement of Wanasundara J in the 13th Amendment Case, Pp. 377 – 379)

With all our criticism of JR for the harmful consequences the country had to face with his open economy and executive presidency introduced after 1977, from the above statement it clearly appears that JR was not a traitor to this country, but a patriot who had some genuine concern for the country and its people. He had the wisdom to see through the danger posed to the very existence of this country as a unitary state by giving into unreasonable and crafty demands of the Tamil political leaders in the North-East.

President Jayewardene not only refused to accept these proposals of the TULF and other Tamil groups; he was not even prepared to discuss them. His firm response was that they are totally unacceptable.

(To be continued)

Opinion

When crisis comes to classroom:

How Sri Lankan children face natural disasters and economic problems

Sri Lanka has always found ways to survive storms. But during the past ten years, the storms have come more often and with more force. Floods have swallowed villages, landslides have buried homes, droughts have dried wells, and cyclones have pushed families out of their coastal towns. Then came the economic crisis in 2022 and 2023, which felt like an invisible disaster happening quietly inside every home. In the middle of all this were our schoolchildren. Their names rarely appeared in newspapers. Many of their stories were never told. A new study brings these voices together and shows how overlapping crises have reshaped education across the island. It also reveals something important: not all children suffered the same way.

This article tells that story through the experiences of teachers, parents and children. It also explains why some regions, some ethnic communities and some families struggled much more than others.

A decade of disruption

Over the past decade, Sri Lanka’s school system has been hit again and again. Floods in Ratnapura, Kalutara and Galle have become almost yearly events. Landslides in Badulla and Nuwara Eliya have cut off whole communities. Cyclones in Batticaloa and Ampara have damaged classrooms and left children in fear. Long droughts in the North and East have forced families to live with empty wells.

Then the economic crisis arrived. It brought fuel shortages, food shortages, transport problems, high prices and a heavy sense of uncertainty. Teachers stood in long queues just to buy a few litres of petrol. Parents struggled to buy exercise books. School buses stopped running. Many children stayed home. A school principal from the hill country said he could not remember a single year without crisis. “One month we have floods. The next month we have landslides,” he said. “The children keep losing learning time.” These experiences echo earlier concerns raised by Angela Little (2003) and Harsha Aturupane (2014), who showed that rural, estate and conflict-affected areas have always faced extra barriers. The new study suggests that recent disasters have made those old inequalities even wider.

When geography decides a child’s future

Sri Lanka is small, but the risks children face depend heavily on where they live. In the flood-prone river areas, schools often close for long periods. Many become temporary shelters filled with families, mats, cooking pots and clothing. Teachers say it can take weeks to clean and reopen classrooms. In the estate sector, children live high in the hills. When a landslide blocks a single narrow road, school simply stops. A teacher in Badulla said she once walked six kilometres during landslide season just to reach her students. “Some days I held on to tree roots to climb,” she said with a tired smile.

In cyclone-prone districts like Batticaloa and Ampara, fear becomes part of childhood. When the wind changes, parents start to worry. School roofs fly off. Books get soaked. Homes crumble. Recovery takes time, and many families cannot afford repairs.

In the drought-hit North and East, children sometimes miss school because they must help their mothers collect water. Teachers say these children return dusty, tired and unable to focus. Lalith Perera (2015) showed how geospatial tools can identify the highest-risk schools. The new study supports his findings and shows that children in these areas lose far more learning days than children in urban schools.

Ethnicity adds another layer to the struggle

Sri Lanka’s ethnic geography shapes children’s lives in deep ways. Tamil families in the North and East still face the long shadow of war-related poverty and lack of resources, as described by Shanmugaratnam (2015) and Samarasinghe (2020). Many schools in these areas are old, understaffed and in poor condition. When a cyclone or drought hits, recovery becomes slow and difficult. A teacher in Mullaitivu said her classroom lost its roof during a storm. “The children sat under a tree for weeks,” she recalled. “They still came. They did not want to fall behind.”

Muslim communities along the Eastern coast face frequent displacement during cyclonic seasons. When fishing families lose their boats and nets, income disappears. Children often miss school because parents cannot afford uniforms or bus fares.

Estate Tamil communities, studied earlier by Little and Jayaweera, continue to face long-term marginalisation. Many children rely heavily on school meal programmes. When the economic crisis disrupted these meals, teachers saw hunger more clearly than ever. Some children fainted in class.

In all these communities, ethnicity and geography combine to create layers of disadvantage that are hard to escape.

The economic crisis: A silent blow to education

The economic crisis of 2022–2023 affected every Sri Lankan home, but its impact was especially hard on low-income families. Economists like Nisha Arunatilake (2022) and Ramani Gunatilaka (2022) have shown how inflation and job losses pushed households into deep stress. These pressures directly affected children’s education.

With no fuel, many teachers could not travel. They walked long distances or hitchhiked. In some schools, several classes were combined because only a few teachers could come. School supplies became expensive. Parents reused old books or bought cheap, low-quality paper. Uniforms were patched many times. Some children wore slippers because shoes were too costly. Food shortages made everything worse. With rising prices, families reduced meals. In the estate sector, teachers saw hunger growing. Attendance fell.

Gender roles also shifted. Girls in rural areas took on childcare and cooking while parents worked longer hours. Boys were pushed into temporary labour. A mother in Monaragala said her teenage son cut timber to support the family. “He comes home exhausted,” she said. “How can he study after that?” Earlier, Selvy Jayaweera (2014) warned that crises deepen gender inequalities. The new study shows that her warning has come true again.

Schools tried to cope, but not all were ready

During field visits, researchers met principals who showed remarkable leadership. Some created disaster committees, organised awareness programmes and kept strong communication with parents. These schools recovered fast. Communities helped clean classrooms. Teachers volunteered for extra lessons. But many schools struggled. Some had no emergency plans. Others had old buildings damaged from past disasters. Some principals lacked training in crisis response. A few schools did not even have complete first aid boxes.

The difference between prepared and unprepared schools became painfully clear. After a cyclone in Batticaloa, one school restarted within a week. A nearby school stayed closed for nearly a month because debris and broken furniture filled the classrooms. Resilience expert Rajib Shaw (2012) highlighted the importance of strong partnerships between schools and communities. This study confirms that his message still holds true.

Families found ways to cope, but children paid the price

Every Sri Lankan family has its own survival strategies. Some borrow money. Some rely on relatives abroad. Some work extra hours. Some move to other districts. But these strategies often disrupt children’s schooling. When a father leaves home for work in another district, children lose emotional support. When a mother works late at a tea estate, older daughters must care for younger siblings. When a family moves temporarily, children lose teachers, routines and friends. A father in Ratnapura said he felt torn. “I want my daughter to study,” he said. “But how can I think of school when the river rises every year and we lose everything?” Years ago, sociologist K. T. Silva (2010) wrote about how poverty and displacement interrupt education. The new study shows that these patterns continue today.

How crises make old inequalities worse

One strong message from the study is that disasters do not create inequality they deepen what already exists. Rural schools with fewer resources suffer greater damage. Estate children who already face hunger become even more vulnerable. Tamil and Muslim families in hazard-prone areas must deal with both environmental and historical burdens.

Climate disasters also come in cycles. One flood does not end the struggle. Children who lose one month of school every year slowly fall behind. Their confidence drops. Their chances of continuing to higher education shrink. Meanwhile, well-resourced urban schools recover quickly. They have strong buildings, better communication and supportive parents. Their losses are small and temporary. The gap between privileged and vulnerable children grows wider each year.

What Sri Lanka can do now

Sri Lanka stands at a turning point. Climate change will bring more storms and droughts. The economy is still fragile. Schools must be prepared.

Every school needs a clear emergency plan. Preparedness should be part of daily school life safer buildings, evacuation routes, first aid training, and strong communication networks. Vulnerable regions need extra support. Flood-prone river basins, cyclone-hit coasts, drought-affected northern districts and the estate sector require more funding and attention. School meals must be protected. For many children, this meal is the difference between hunger and hope.

Teachers need help with transport and crisis training. Families need social protection so children are not forced into labour or long absences. Most importantly, education policy must place fairness at the centre. As Aturupane (2014) explained, equality cannot be achieved by giving all schools the same amount. Some schools need more because their burdens are heavier.

Stories that should guide policy

The most powerful part of this research is not the statistics. It is the stories:

A boy in Ratnapura losing his schoolbag to the floods.A teacher in Badulla walking through mud for her students.A mother in Batticaloa cooking in a cyclone shelter.A girl in Mullaitivu studying under a tree after her classroom roof blew away.A Muslim family in Ampara sheltering in a mosque during every storm.A Tamil child in Kilinochchi missing school to fetch water during drought.

These are the voices policymakers must listen to.

A future that values every child

Sri Lanka’s future depends on the minds of its children. If classrooms become unstable places, the country’s future becomes uncertain. But there is hope. Many teachers showed deep dedication. Many parents worked tirelessly to keep their children in school. Many communities showed unity and strength. If the government builds on this resilience through better planning, fairer funding and stronger support for vulnerable regions children’s dreams can survive the storms ahead. What we choose today will decide whether the next generation inherits disaster or opportunity.

References

Aturupane, H. (2014). Equity and Access in Sri Lankan Education. World Bank.Arunatilake, N. (2022). Economic Vulnerability and Social Protection in Times of Crisis. Institute of Policy Studies.Fernando, P. (2018). Household Vulnerability and Educational Participation in Rural Sri Lanka. SAGE Publications.Gunatilaka, R. (2022). The Impact of Economic Shocks on Sri Lankan Households. International Labour Organization.Jayaweera, S. (2014). Gender Dimensions of Educational Inequality in Sri Lanka. Centre for Women’s Research.Little, A. W. (2003). Education, Conflict and Social Cohesion in Sri Lanka. UNESCO.Perera, L. (2015). Geospatial Approaches to Educational Planning in Disaster-Prone Regions. Asian Development Bank.Samarasinghe, V. (2020). Regional Inequalities and Social Exclusion in Sri Lanka. Routledge.Shanmugaratnam, N. (2015). Post-War Development and Marginalisation in Northern Sri Lanka. Nordic Asia Press.Shaw, R. (2012). Community-Based Disaster Risk Reduction and School Resilience. Earthscan.Silva, K. T. (2010). Poverty, Displacement, and Educational Access in Sri Lanka. Social Scientists’ Association.UNICEF Sri Lanka. (2018). School Safety and Disaster Preparedness in Sri Lanka.

Opinion

The policy of Sinhala Only and downgrading of English

In 1956 a Sri Lankan politician riding a great surge of populism, made a move that, at a stroke, disabled a functioning civil society operating in the English language medium in Sri Lanka. He had thrown the baby out with the bathwater.

It was done to huge, ecstatic public joy and applause at the time but in truth, this action had serious ramifications for the country, the effects have, no doubt, been endlessly mulled over ever since.

However, there is one effect/ aspect that cannot be easily dismissed – the use of legal English of an exact technical quality used for dispensing Jurisprudence (certainty and rational thought). These court certified decisions engendered confidence in law, investment and business not only here but most importantly, among the international business community.

Well qualified, rational men, Judges, thought rationally and impartially through all the aspects of a case in Law brought before them. They were expert in the use of this specialised English, with all its meanings and technicalities – but now, a type of concise English hardly understandable to the casual layman who may casually look through some court proceedings of yesteryear.

They made clear and precise rulings on matters of Sri Lankan Law. These were guiding principles for administrative practice. This body of case law knowledge has been built up over the years before Independence. This was in fact, something extremely valuable for business and everyday life. It brought confidence and trust – essential for conducting business.

English had been developed into a precise tool for analysing and understanding a problem, a matter, or a transaction. Words can have specific meanings, they were not, merely, the play- thing of those producing “fake news”. English words as used at that time, had meaning – they carried weight and meaning – the weight of the law!

Now many progressive countries around the world are embracing English for good economic and cultural reasons, but in complete contrast little Sri Lanka has gone into reverse!

A minority of the Sinhalese population, (the educated ones!) could immediately see at the time the problems that could arise by this move to down-grade English including its high-quality legal determinations. Unfortunately, seemingly, with the downgrading of English came a downgrading of the quality of inter- personal transactions.

A second failure was the failure to improve the “have nots” of the villagers by education. Knowledge and information can be considered a universal right. Leonard Woolf’s book “A village in the Jungle” makes use of this difference in education to prove a point. It makes infinitely good politics to reduce this education gap by education policies that rectify this important disadvantage normal people of Sri Lanka have.

But the yearning of educators to upgrade the education system as a whole, still remains a distant goal. Advanced English spoken language is encouraged individually but not at a state level. It has become an orphaned child. It is the elites that can read the standard classics such as Treasure Island or Sherlock Holmes and enjoy them.

But, perhaps now, with the country in the doldrums, more people will come to reflect on these failures of foresight and policy implementation. Isn’t the doldrums all the proof you need?

by Priyantha Hettige

Opinion

GOODBYE, DEAR SIR

It is with deep gratitude and profound sorrow that we remember Mr. K. L. F. Wijedasa, remarkable athletics coach whose influence reached far beyond the track. He passed away on November 4, exactly six months after his 93rd birthday, having led an exemplary and disciplined life that enabled him to enjoy such a long and meaningful innings. To those he trained, he was not only a masterful coach but a mentor, a friend, a steady father figure, and an enduring source of inspiration. His wisdom, kindness, and unwavering belief in every young athlete shaped countless lives, leaving a legacy that will continue to echo in the hearts of all who were fortunate enough to be guided by him.

I was privileged to be one of the many athletes who trained under his watchful eye from the time Mr. Wijedasa began his close association with Royal College in 1974. He was largely responsible for the golden era of athletics at Royal College from 1973 to 1980. In all but one of those years, Royal swept the board at all the leading Track & Field Championships — from the Senior and Junior Tarbat Shields to the Daily News Trophy Relay Carnival. Not only did the school dominate competitions, but it also produced star-class athletes such as sprinter Royce Koelmeyer; sprint and long & triple jump champions Godfrey Fernando and Ravi Waidyalankara; high jumper and pole vaulter Cletus Dep; Olympic 400m runner Chrisantha Ferdinando; sprinters Roshan Fernando and the Indraratne twins, Asela and Athula; and record-breaking high jumper Dr. Dharshana Wijegunasinghe, to name just a few.

Royal had won the Senior & Junior Tarbats as well as the Relay Carnival in 1973 by a whisker and was looking for a top-class coach to mould an exceptionally talented group of athletes for 1974 and beyond. This was when Mr. Wijedasa entered the scene, beginning a lifelong relationship with the athletes of Royal College from 1974 to 1987. He received excellent support from the then Principal, late Mr. L. D. H. Pieris; Vice Principal, late Mr. E. C. Gunesekera; and Masters-in-Charge Mr. Dharmasena, Mr. M. D. R. Senanayake, and Mr. V. A. B. Samarakone, with whom he maintained a strong and respectful rapport throughout his tenure.

An old boy of several schools — beginning at Kandegoda Sinhala Mixed School in his hometown, moving on to Dharmasoka Vidyalaya, Ambalangoda, Moratu Vidyalaya, and finally Ananda College — he excelled in both sports and studies. He later graduated in Geography, from the University of Peradeniya. During his undergraduate days, he distinguished himself as a sprinter, establishing a new National Record in the 100 metres in 1955. Beyond academics and sports, Mr. Wijedasa also demonstrated remarkable talent in drama.

Though proudly an Anandian, he became equally a Royalist through his deep association with Royal’s athletics from the 1970s. So strong was this bond that he eventually admitted his only son, Duminda, to Royal College. The hallmark of Mr. Wijedasa was his tireless dedication and immense patience as a mentor. Endurance and power training were among his strengths —disciplines that stood many of us in good stead long after we left school.

More than champions on the track, it is the individuals we became in later life that bear true testimony to his loving guidance. Such was his simplicity and warmth that we could visit him and his beloved wife, Ransiri, without appointment. Even long after our school days, we remained in close touch. Those living overseas never failed to visit him whenever they returned to Sri Lanka. These visits were filled with fond reminiscences of our sporting days, discussions on world affairs, and joyful moments of singing old Sinhala songs that he treasured.

It was only fitting, therefore, that on his last birthday on May 4 this year, the Old Royalists’ Athletic Club (ORAC) honoured him with a biography highlighting his immense contribution to athletics at Royal. I was deeply privileged to co-author this book together with Asoka Rodrigo, another old boy of the school.

Royal, however, was not the first school he coached. After joining the tutorial staff of his alma mater following graduation, he naturally coached Ananda College before moving on to Holy Family Convent, Bambalapitiya — where he first met the “love of his life,” Ransiri, a gifted and versatile sportswoman. She was not only a national champion in athletics but also a top netballer and basketball player in the 1960s. After his long and illustrious stint at Royal College, he went on to coach at schools such as Visakha Vidyalaya and Belvoir International.

The school arena was not his only forte. Mr. Wijedasa also produced several top national athletes, including D. K. Podimahattaya, Vijitha Wijesekera, Lionel Karunasena, Ransiri Serasinghe, Kosala Sahabandu, Gregory de Silva, Sunil Gunawardena, Prasad Perera, K. G. Badra, Surangani de Silva, Nandika de Silva, Chrisantha Ferdinando, Tamara Padmini, and Anula Costa. Apart from coaching, he was an efficient administrator as Director of Physical Education at the University of Colombo and held several senior positions in national sporting bodies. He served as President of the Amateur Athletic Association of Sri Lanka in 1994 and was also a founder and later President of the Ceylonese Track & Field Club. He served with distinction as a national selector, starter, judge, and highly qualified timekeeper.

The crowning joy of his life was seeing his legacy continue through his children and grandchildren. His son, Duminda, was a prominent athlete at Royal and later a National Squash player in the 1990s. In his later years, Mr. Wijedasa took great pride in seeing his granddaughter, Tejani, become a reputed throwing champion at Bishop’s College, where she currently serves as Games Captain. Her younger brother, too, is a promising athlete.

He is survived by his beloved wife, Ransiri, with whom he shared 57 years of a happy and devoted marriage, and by their two children, Duminda and Puranya. Duminda, married to Debbie, resides in Brisbane, Australia, with their two daughters, Deandra and Tennille. Puranya, married to Ruvindu, is blessed with three children — Madhuke, Tejani, and Dharishta.

Though he has left this world, the values he instilled, the lives he shaped, and the spirit he ignited on countless tracks and fields will live on forever — etched in the hearts of generations who were privileged to call him Sir (Coach).

NIRAJ DE MEL, Athletics Captain of Royal College 1976

Deputy Chairman, Old Royalists’ Athletics Club (ORAC)

-

Features5 days ago

Features5 days agoFinally, Mahinda Yapa sets the record straight

-

News6 days ago

News6 days agoCyclone Ditwah leaves Sri Lanka’s biodiversity in ruins: Top scientist warns of unseen ecological disaster

-

Features5 days ago

Features5 days agoHandunnetti and Colonial Shackles of English in Sri Lanka

-

Business4 days ago

Business4 days agoCabinet approves establishment of two 50 MW wind power stations in Mullikulum, Mannar region

-

News4 days ago

News4 days agoGota ordered to give court evidence of life threats

-

Features6 days ago

Features6 days agoAn awakening: Revisiting education policy after Cyclone Ditwah

-

Features4 days ago

Features4 days agoCliff and Hank recreate golden era of ‘The Young Ones’

-

Opinion5 days ago

Opinion5 days agoA national post-cyclone reflection period?