Midweek Review

Exquisite intermingling of the novelistic and the poetic

by Liyanage Amarakeerthi

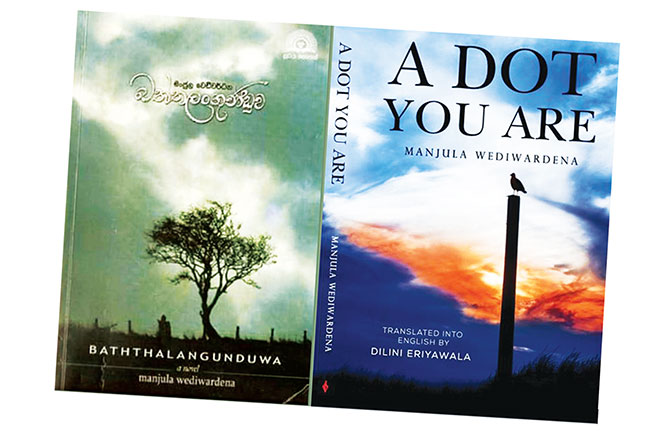

A debut novel rarely achieves the same excellence as Baththalangunduwa by Manjula Wediwardena. In any language, such first-novels are rare. Still there are many writers who have mesmerised readers with their first novels. This is certainly one among them. In writing this novel, the author does not hide the fact that he arrives at the art of novel, bringing with him the technical devices of poetry and short play, two genres he had excelled in earlier. He uses those elements to create a style that makes his novel a sensation in the contemporary Sinhala novel. The book has been translated into English. This essay, though based on Baththalangunduwa, is about the significance of style in a novel.

One of the challenges that new writers face is to create a ‘new language’ for the Sinhala novel. Not to argue that a single style fits all, but style is one area in which a writer can establish the novelty of his work. Our writers seldom experiment with language to create a style that is both simple and attractive at the same time. When it comes to experimentation with narrative techniques, even young writers do not show the youthfulness found in the work of senior writers such as Ajith Thilakasena, Siri Gunasinghe, Simon Nawagatthegama or Tennyson Perera, to name a few. Naturalist realism becomes rather stale, if it is not presented in an innovative style or using other experimental narrative devices. The realist mode is, however, extremely malleable, and an inventive writer can still make it look surprisingly fresh if he or she is imaginative enough with regard to the technical devices of fiction writing. Stories can be crafted in numerous ways. Possibilities of fiction can never be exhausted. Every once in a while, a writer or two appears to remind us about those possibilities. In recent times, Manjula Wediwardena was one such writer. Of late, there are others but we are yet to see if they would continue to develop literary careers.

Tissa Abeysekera, one of our greatest writers, points out this problem of style and language in his excellent collection of essays, Roots, Reflections and Reminiscences. In it, Abeysekera argues that even though Martin Wickramasinghe was able to produce a language for the realist novel in Sinhala no writer was able to surpass him. Abeysekera goes on to argue that Viragaya (The Way of the Lotus) is the pinnacle of the Sinhala novel. It can be said that this is an accurate observation. One can agree that Viragaya is an immortal novel. Yet, the weakness of Abesekara’s argument is that it does not mention any writer who has apparently attempted to surpass Wickramasinghe. The novels of Simon Nawagattegama, for example, are excellent examples of creating a fresh style of language for each novel. The characters or the environment of Dadayakkarayage Kathawa (The story of the Hunter), or Ksheera Sagaraya Kelambina (The Milky Ocean is Churned) cannot be properly portrayed in the language of Wickramasinghe’s Gamperaliya (Uprooted). Furthermore, those novels have levels of reality whose existence is predicated upon the existence of a unique language, and Nawagattegama creates that language. Let’s look at a paragraph of The story of the Hunter, even though it is hard to make my point in a translated segment:

“Those who belonged to the lineage of the hunter had no satisfaction by merely being hunters. To be a shooter, one only has to train himself in shooting a target. It is not such a big deal to brag about either. Is it? Even though one can aim at an animal and shoot it down, even though one can shoot every day all the animals one sees and carry them to the village, it only shows that one has already committed so much sin and one still has Karmic disposition to acquire sins that can bring Karmic fruits for five hundred lives to come. Does it not?”

The language of this novel is formed in such a way that it focalizes the story through the life and point of view of the hunter. This style takes the reader into the hunter’s consciousness and sustains the reader within the level of reality, where the hunter dwells.

Misconception

There is a misconception that there exists language or style suitable for all novels. It is an opinion constantly repeated by popular literary journalists. Poetic talents can be extremely useful for a novelist. More often than not, it gives immense pleasure to read novels written by poets. All novels by Michael Ondaatje are like long poems. Yet, each of his novels has its own language. If anyone expects a single language or style from all his novels, he simply does not know the meaning of novelized language. A British critic once claimed to have found Ondaatje’s Anil’s Ghost a bit too poetic, and might have reasons for that argument.

Possession by A.S. Byatt is very much a poetic novel, and there is a narrative reason for it: It is a story of love between a poet and a poetess. One might not be able to write a novel of that kind without a great deal of poetic skill within oneself. Byatt writes in a beautifully poetic language. The Blue Flower by Penelope Fitzgerald is also a captivating novel about the life of the German poet Novalis. In it, the author’s controlled-use of poetry within the novel contributes considerably to the book’s immense attraction. That Pasternak’s Doctor Zhivago is poetic should not surprise anyone, for it is an epic of the life of a poet. But there poetry does not intermingle with prose. It is true that there are so much poetic description nearly everywhere in the book. But what is obviously poetic is included as a collection of Zhivago’s poems, at the end of the book. So negligible was the connection of poems to the structure of the novel, that the poems were later published as a separate book. Separation of that kind is not possible in Possession, where after every few pages poetic sections appear, helping to advance the plot. The immense appeal of Rainer Maria Rilke’s stunning novel, The Notebooks of Malte Laurids Brigge, is predicated upon the author’s undisputed skills in poetry. In some ways, it is a Campu written in German translated into English!

Prose or Campu

Vilasiniyakage Premaya (The Love of a Courtesan) by Ediriweera Sarachchandra is a Campu poem, as the author prefers to name it. In a Campu, verses are a part of the structure because it is a genre that uses a mixture of prose and verse. In it, verses are used to express the inner feelings of characters, to express interior monologues or to send some coded message. Another novel that deals with poets, poetry and poetic talents is Milan Kundera’s Life is Elsewhere. It is clear from Baththalangunduwa itself, that Wediwardena has been heavily influenced by Kundera’s novel. Intertextual significations the Sinhala novel develops by constantly referring to Life is Elsewhere, and in reading it, an experienced reader is regularly reminded of many other novels in which the novelist and the poetry merge in an exquisite union. In the manner the author uses language in the novel, it is very much comparable with numerous other novels mentioned above.

A good novel, among other things, creates a style that refreshes the language of contemporary fiction. Baththalangunduwa does refresh the language of the Sinhala novel or novelistic Sinhala. Though there have been many recent newcomers to the genre, the promise made by those novels to renew novelistic Sinhala has not always been kept. Hundreds of novels are routinely published, written in a style which fails to attract and surprise us with its beauty and artistic fineness. Only a few novelists, Sunethra Rajakarunanayake for example, delivered on the promise, by writing several innovative novels. Perhaps, it has a lot to do with the fact that a style alone cannot give a novel lasting substance.

Insights into human life

Why have we failed to sustain the genre of novel as a text that generates unique insights into human life and society? Some Sinhala writers use attractive styles, but their thinking is a bit too plain to make them great novelists. Conservatism of thought has been plaguing the Sinhala novel in recent years. Cultural nationalism, as the most dominant ideology in the country, gets in the way of achieving literary greatness. In fact, the same nationalism, which is extremely conservative about the language, is one of the greatest obstacles for inventive writers. More often than not, writers who break away from conservative grammatical traditions, have to face considerable hostility from conservative thinkers. Wediwardena seems to be aware of these challenges. This book has a new style and a new content, and they supplement each other beautifully. Moreover, the book’s thematic content cannot be separated from its style.

This novel is quite minimal in its content. In time and space too, the novel’s scope is limited. For that very reason, its style is the central feature that breathes life into the text. Usually, a novel, which focuses on a relatively small life-world situated within a small space and short time period, places greater emphasis on its style. Such a novel aims to achieve its completeness through an innovative and captivating style. Baththalangunduwa is such a novel. There are such novels in world literature as well. William Faulkner’s As I Lay Dying, J.D. Salinger’s Catcher in the Rye, Upamanyu Chatterjee’s English August, for example, have achieved excellence primarily through their styles. Novels like, Karamazov Brothers, War and Peace, or Anna Karenina are so grand in their theme and scope that they achieve greatness even without any particular inventiveness in style. That is not to say that Tolstoy was not a great stylist. He certainly was, and there are memorable sentences and paragraphs everywhere in his novels.

Wediwardena’s novel tells a story set in an Island of the North-Western coast of Sri Lanka, and the novel becomes unique simply because of the sub-culture of the fishing community of the island. But he still faces the challenge of inventing a style suitable to create the world of that community in his text. He does invent that style wonderfully.

The challenge he had to face was a complex one. The community he is writing about is different from Sinhala Buddhists, which make up the largest chunk of the cultural world of Sri Lanka, and the community in this small island is different from the mainstream Christian community living on the main island. This small island is an island in the cultural sense as well. It is a tiny island that belongs to a larger island. The writer, writing in Sinhala, has to portray this small fishing community in a manner accessible to the readers living in the main island, who have little or no knowledge of this sub-cultural group.

In addition, there is another challenge, perhaps much more demanding: Sinhala language is mainly a product of Buddhist culture and many Sinhala words have Buddhist connotations. The majority of novel readers in Sinhala are also Buddhist. They know very little about Christian communities and much less about fishing communities in these small islands. In this sense, writing about Baththalangunduwa, the island, is as difficult as writing about a foreign land.

Son searching for father, father in search of son

The other side of Wediwardena’s challenge is even more complex: When the narrator-son goes to this remote island to look for his father, he is a young man exposed to the postmodernist conditions in Colombo. He takes with him a Sinhala translation of Milan Kundera’s Life is Elsewhere. It is through this character that the fishing island and its people are presented to us. Thus, the challenge of style gets even more complicated. The writer has to come up with a style that can hold together two worlds, which are strikingly different from each other: The postmodern urban world of the son and the unsophisticated life of the fishing community, where the father makes his home. It does not end there. Since the narrator is a poet, the style of the novel needs to be one that can facilitate poetic sensibilities. As I see it, the author successfully meets all these challenges. At times, the novel’s style is too poetic to be novelistic but, in the main, it is able to breathe life into ‘postmodern Antony’, (the son) and the men and women in the fishing community. The style wonderfully absorbs fishermen’s wisdom of the ocean without destroying their epistemological foundations. In other words, those folkloric views of the fishing community enter the author’s prose without being subjected to any rationalist comments of an urban observer. Thus, one is able to listen to the most beautiful descriptions of the ocean through the dialogues of those fishermen.

Though characters of a novel exist in language, characterisation largely belongs to the plot. The complications of characters appear in the way they react to different incidents of the story. But in this novel, the style is instrumental in characterisation as well. Wediwardena allows the language of these Island-dwelling fishermen to merge with the author’s narration in a way that provides important glimpses into the lives of those men and women.

This novel does not have large dramatic events. Thus, the plot is not all that crucial in characterisation. Instead, the author skillfully uses his style to present his unique characters.

Organic connections with characters

The author deeply loves the characters he portrays and he is honest to life there on the island. Consequently, very much like the main character, Antony, the writer himself has no hesitation in mingling with life on the island. He is not a detached observer of that life. Antony does not detach himself from the community in the island as an elitist visitor from Colombo. But rather he eats, drinks and have sexual relationships with those people. The ethical rationality that undergirds those activities is not something brought from metropolitan Colombo; it is a form of ethics unique to the island. Both Antony and his father share everything that the island offers: food, drink, lodging, and even sex. For the conservative moralists, the island might look like an abode of sin. But the ideal reader of the novel, the reader this novel seeks to ‘create’ might see this island as a place where primordial innocence still exists. That innocence is something we have lost with the advent of modern life. It would not be surprising for the reader to feel like eating fish curry, drinking locally made illegal alcohol with those fisher folk and making love freely as they normally do. This aesthetic effect is achieved primarily through style.

New facet of Sinhalaness

This novel shows us another beautiful facet of Sinhala culture. The culture of this island made with Catholic faith, the trade of fishing and folkloric beliefs about the ocean should also belong in the Sinhala culture at large. Some of the Sinhala people on this island only speak Tamil. But the island is open to Milan Kundera. It is clear from the way the culture of this island intermingles with other cultures that no culture is pure or impure. This novel reminds us of Sri Lanka’s cultural diversity and the intricate connections among different cultural elements. This is, perhaps, one thematic dimension that could have been developed further.

In this novel the impressionist portrayal of life on the island is prioritised over elucidating a strong thematic line. The novel revolves around the trip Antony makes to see his father, the meeting of the father and the eventual separation. What are the themes of this journey; of the search for his father; or of seducing the father’s girlfriend? Is it a case of a son seducing his symbolic mother? Our author does not allow us to make any thematic summaries of the plot. In Faulkner’s As I lay dying, a family takes a dead woman’s body across the Southern US to bury her. That journey itself makes much of the novel. But the mythical allure of the journey lends itself to multiple meanings. Antony’s trip to this exotic island has that mythical quality, whose realization perhaps needed better care. Still Baththalangunduwa is one of the most original works of fiction to be published in recent times.

(Amarakeerthi is a professor of Sinhala, University of Peradeniya)

Midweek Review

Taking time to reflect on Sri Lanka’s war against terrorism in the wake of Pahalgam massacre

The recent security alert on a flight from Chennai for a person who had been allegedly involved in the recent massacre in Indian-administered Kashmir seems to have been a sort of psychological warfare. The question that arises is as to why UL 122 hadn’t been subjected to checks there if Indian authorities were aware of the identity of the wanted person.

Authorities there couldn’t have learnt of the presence of the alleged suspect after the plane left the Indian airspace

The recent massacre of 25 Indians and one Nepali at Pahalgam in Kashmir attracted international attention. Amidst the war on Gaza, Israeli air strikes on selected targets in the region, particularly Syria, Russia-Ukraine war, and US-UK air campaign against Houthis, the execution-style killings at Pahalgam, in the Indian-administered Kashmir, caused concerns over possible direct clash between nuclear powers India and Pakistan.

Against the backdrop of India alleging a Pakistani hand in the April 22, 2025, massacre and mounting public pressure to hit back hard at Pakistan, Islamabad’s Defence Minister khawaja Muhammad Asif’s declaration that his country backed/sponsored terrorist groups over the years in line with the US-UK strategy couldn’t have been made at a better time. The Pakistani role in notorious Western intelligence operations is widely known and the killing of al Qaeda leader Osama bin Laden in May 2011 in the Pakistani garrison city of Abbottabad, named after Major James Abbott, the first Deputy Commissioner of the Hazara District under British rule in 1853, underscored the murky world of the US/UK-Pakistan relations.

Interestingly, Asif said so during an interview with British TV channel Sky News. Having called their decision to get involved in dirty work on behalf of the West a mistake, the seasoned politician admitted the country suffered due to that decision.

Asif bluntly declared that Pakistan got involved in the terrorism projects in support of the West after the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan in late Dec. 1979 and Al Qaeda attacks on the US in Sept. 2001. But, bin Laden’s high profile killing in Pakistan proved that in spite of Islamabad support to the US efforts against al Qaeda at least an influential section of the Pakistan establishment all along played a double game as the wanted man lived under Pakistan protection.

Perhaps Asif’s declaration meant that Pakistan, over the years, lost control over various groups that it sponsored with the explicit understanding of the West. India pounced on Asif’s statement.

The PTI quoted India’s Deputy Permanent Representative to the UN, Ambassador Yojna Patel, as having said: “The whole world has heard the Pakistani Defence Minister Khawaja Asif admitting and confessing Pakistan’s history of supporting, training and funding terrorist organisations in a recent television interview.” The largest news agency in India quoted Patel further: “This open confession surprises no one and exposes Pakistan as a rogue state fuelling global terrorism and destabilising the region. The world can no longer turn a blind eye. I have nothing further to add.”

Would Patel also care to comment on the US and the UK utilising Pakistan to do their dirty work? Pakistani admission that it supported, trained and funded terrorist organisations should be investigated, taking into consideration Asif’s declaration that those terror projects had been sanctioned by the West. Pakistan’s culpability in such operations cannot be examined without taking into consideration the US and British complicity and status of their role.

The US strategy/objectives in Afghanistan had been similar to their intervention in Ukraine. Western powers wanted to bleed the Soviet Union in Afghanistan and now they intended to do the same to Russia in Ukraine.

Those interested in knowing Pakistan’s role in the US war against the Soviet Union should access ‘Operation Cyclone’ the codename given to costly CIA action in the ’80s.

At the time Pakistan got involved in the CIA project meant to build up anti-Soviet groups in Afghanistan, beginning in the early ’80s, India had been busy destabilising Sri Lanka. India established a vast network of terrorist groups here to achieve what can be safely described as New Delhi’s counter strategic, political and security objectives. New Delhi feared the US-Pakistan-Israeli relations with President JRJ’s government and sought to undermine them by consolidating their presence here.

The late J.N. Dixit, who served here as India’s top envoy during the volatile 1985-1989 period, in his memoirs ‘Makers of India’s Foreign Policy: Raja Ram Mohun Roy to Yashwant Sinha,’ faulted Premier Gandhi on two key foreign policy decisions. The following is the relevant section verbatim: “…her ambiguous response to the Russian intrusion into Afghanistan and her giving active support to Sri Lankan Tamil militants. Whatever the criticism about these decisions, it cannot be denied that she took them on the basis of her assessments about India’s national interests. Her logic was that she couldn’t openly alienate the former Soviet Union when India was so dependent on that country for defence supplies and related technology transfers. Similarly, she could not afford the emergence of Tamil separatism in Tamil Nadu by refusing to support the aspirations of Sri Lankan Tamils.”

Dixit, in short, has acknowledged India’s culpability in terrorism in Sri Lanka. Dixit served as Foreign Secretary (1991-1994) and National Security Advisor (May 2004-January 2005). At the time of his death he was 68. The ugly truth is whatever the reasons and circumstances leading to Indira Gandhi giving the go ahead to the establishment to destabilise Sri Lanka, no less a person than Dixit, who had served as Foreign Secretary, admitted that India, like Pakistan, supported, trained and funded terrorist groups.

In fact, Asif’s admission must have embarrassed both the US, the UK, as well as India that now thrived on its high profile relationship with the US. India owed Sri Lanka an explanation and an apology for what it did to Sri Lanka that led to death and destruction. New Delhi had been so deeply entrenched here in late 1989/early 1990 that President Premadasa pushed for total withdrawal of the Indian Army deployed here (July 1987- March 1990) under Indo-Lanka peace accord that was forced on President JRJ. However, prior to their departure, New Delhi hastily formed the Tamil National Army (TNA) in a bid to protect Varatharaja Perumal’s puppet administration.

A lesson from India

Sri Lankan armed forces paid a very heavy price to bring the Eelam war to an end in May 2009. The Indian-trained LTTE, having gained valuable battlefield experience at the expense of the Indian Army in the Northern and Eastern regions in Sri Lanka, nearly succeeded in their bloody endeavour, if not for the valiant team President Mahinda Rajapaksa gathered around him to meet that mortal threat to the country, ably helped by his battle hardened brother Gotabaya. The war was brought to a successful conclusion on May 19, 2009, when a soldier put a bullet through Velupillai Prabhakaran’s head during a confrontation on the banks of the Nanthikadal lagoon.

In spite of the great sacrifices the armed forces made, various interested parties, at the drop of a hat, targeted the armed forces and police. The treacherous UNP-SLFP Yahapalana administration sold out our valiant armed forces at the Geneva–based United Nations Human Rights Council, in 2015, to be on the good books of the West, not satisfied with them earlier having mocked the armed forces when they achieved victories that so-called experts claimed the Lankan armed forces were incapable of achieving, and after they were eventually proved wrong with the crushing victory over the Tigers in the battlefield, like sour grapes they questioned the professionalism of our armed forces and helped level baseless war crimes allegations. Remember, for example, when the armed forces were about to capture the LTTE bastion, Kilinochchi, one joker UNP politico claimed they were only at Medawachiya. Similarly when forces were at Alimankada (Elephant Pass) this vicious joker claimed it was Pamankada.

Many eyebrows were raised recently when President Anura Kumara Dissanayake, who also holds the Defence portfolio, too, questioned the professionalism of our war-winning armed forces.

Speaking in Parliament, in early March, during the Committee Stage debate on the 2025 Budget, President Dissanayake assured that the government would ensure the armed forces achieved professional status. It would be pertinent to mention that our armed forces defeated JVP terrorism twice, in 1971 and 1987-1990, and also separatist Tamil terrorism. Therefore, there cannot be absolutely any issue with regard to their professionalism, commitment and capabilities.

There had been many shortcomings and many lapses on the part of the armed forces, no doubt, due to short-sighted political and military strategies, as well as the absence of preparedness at crucial times of the conflict. But, overall, success that had been achieved by the armed forces and intelligence services cannot be downplayed under any circumstances. Even the 2019 Easter Sunday carnage could have been certainly averted if the then political leadership hadn’t played politics with national security. The Yahapalana Justice Minister hadn’t minced his words when he declared that President Maithripala Sirisena and Premier Ranil Wickremesinghe allowed the extremist build-up by failing to deal with the threat, for political reasons, as well as the appointment of unsuitable persons as Secretary Defence and IGP. Political party leaders, as usual, initiated investigations in a bid to cover up their failures before the Presidential Commission of Inquiry (PCoI) appointed in late 2019 during the tail end of Sirisena’s presidency, exposed the useless lot.

Against the backdrop of the latest Kashmir bloodshed, various interested parties pursued strategies that may have undermined the collective Indian response to the terrorist challenge. Obviously, the Indian armed forces had been targeted over their failure to thwart the attack. But, the Indian Supreme Court, as expected, thwarted one such attempt.

Amidst continuing public furore over the Pahalgam attack, the Indian Supreme Court rejected a public interest litigation (PIL) seeking a judicial inquiry by a retired Supreme Court judge into the recent incident. A bench comprising Justices Surya Kant and NK Singh dismissed the plea filed by petitioner Fatesh Sahu, warning that such actions during sensitive times could demoralise the armed forces.

Let us hope Sri Lanka learnt from that significant and far reaching Indian SC directive. The Indian media extensively quoted the bench as having said: “This is a crucial moment when every Indian stands united against terrorism. Please don’t undermine the morale of our forces. Be mindful of the sensitivity of the issue.”

Perhaps the most significant remarks made by Justice Surya Kant were comments on suitability of retired High Court and Supreme Court judges to conduct investigations.

Appointment of serving and retired judges to conduct investigations has been widely practiced by successive governments here as part of their political strategy. Regardless of constitutionality of such appointments, the Indian Supreme Court has emphasised the pivotal importance of safeguarding the interests of their armed forces.

The treacherous Yahapalana government betrayed our armed forces by accepting a US proposal to subject them to a hybrid judicial mechanism with the participation of foreign judges. The tripartite agreement among Sri Lanka, the US and the Tamil National Alliance (TNA) that had been worked out in the run-up to the acceptance of an accountability resolution at the UNHRC in Oct. 2015, revealed the level of treachery Have you ever heard of a government betraying its own armed forces for political expediency.

There is absolutely no ambiguity in the Indian Supreme Court declaration. Whatever the circumstances and situations, the armed forces shouldn’t be undermined, demoralised.

JD on accountability

In line with its overall response to the Pahalgam massacre, India announced a series of sweeping punitive measures against Pakistan, halting all imports and suspending mail services. These actions were in addition to diplomatic measures taken by Narendra Modi’s government earlier on the basis Islamabad engineered the terrorist attack in southern Kashmir.

A notification issued by the Directorate General of Foreign Trade on May 2, 2025 banned “direct or indirect import or transit of all goods originating in or exported from Pakistan, whether or not freely importable or otherwise permitted” with immediate effect.

India downgraded trade ties between the two countries in February 2019 when the Modi government imposed a staggering 200% duty on Pakistani goods. Pakistan responded by formally suspending a large part of its trade relations with India. India responded angrily following a vehicle borne suicide attack in Pulwama, Kashmir, that claimed the lives of 40 members of the Central Reserve Police Force (CPRF).

In response to the latest Kashmir attack, India also barred ships carrying the Pakistani flag from docking at Indian ports and prohibited Indian-flagged vessels from visiting Pakistani ports.

But when India terrorised hapless Sri Lanka, the then administration lacked the wherewithal to protest and oppose aggressive Indian moves.

Having set up a terrorist project here, India prevented the government from taking measures to neutralise that threat. The Indian Air Force flew in secret missions to Jaffna and invaded Sri Lanka airspace to force President JRJ to stop military action before the signing of the so-called peace accord that was meant to pave the way for the deployment of its Army here.

Even during the time the Indian Army battled the LTTE terrorists here, Tamil Nadu allowed wounded LTTE cadres to receive medical treatment there. India refrained from interfering in that despicable politically motivated practice. India allowed terrorists to carry weapons in India. The killing of 12 EPRLF terrorists, including its leader K. Padmanabha in June 1990, on Indian soil, in Madras, three months after India pulled out its Army from Sri Lanka, is a glaring example of Indian duplicity.

Had India acted at least after Padmanabha’s killing, the suicide attack on Rajiv Gandhi in May 1991 could have been thwarted.

One of Sri Lanka’s celebrated career diplomats, the late Jayantha Dhanapala, discussed the issue of accountability when he addressed the Lessons Learnt and Reconciliation Commission (LLRC), headed by one-time Attorney General, the late C. R. de Silva, on 25 August, 2010.

Dhanapala, in his submissions, said: “Now I think it is important for us to expand that concept to bring in the culpability of those members of the international community who have subscribed to the situation that has caused injury to the civilians of a nation. I talk about the way in which terrorist groups are given sanctuary; harbored; and supplied with arms and training by some countries with regard to their neighbours or with regard to other countries. We know that in our case this has happened, and I don’t want to name countries, but even countries which have allowed their financial procedures and systems to be abused in such a way that money can flow from their countries in order to buy arms and ammunition that cause deaths, maiming and destruction of property in Sri Lanka are to blame and there is, therefore, a responsibility to protect our civilians and the civilians of other nations from that kind of behaviour on the part of members of the international community. And I think this is something that will echo within many countries in the Non-Aligned Movement, where Sri Lanka has a much respected position and where I hope we will be able to raise this issue.”

Dhanapala also stressed on the accountability on the part of Western governments, which conveniently turned a blind eye to massive fundraising operations in their countries, in support of the LTTE operations. It is no secret that the LTTE would never have been able to emerge as a conventional fighting force without having the wherewithal abroad, mainly in the Western countries, to procure arms, ammunition and equipment. But, the government never acted on Dhanapala’s advice.

By Shamindra Ferdinando

Midweek Review

Masters, not just graduates: Reclaiming purpose in university education

A Critique of the Sri Lankan Education System: The Crisis of Producing Masters

For decades, the Sri Lankan education system has been subject to criticism for its failure to nurture true masters within each academic and professional discipline. At the heart of this issue lies a rigid, prescriptive structure that compels students to strictly adhere to pre-designed course modules, leaving little room for creativity, independent inquiry, or the pursuit of personal intellectual passions.

Although modern curricular frameworks may appear to allocate space for creativity and personal exploration, in practice, these opportunities remain superficial and ineffective. The modules that are meant to encourage innovation and critical thinking often fall short because students are still bound by rigid assessment criteria and narrowly defined outcomes. As a result, students are rarely encouraged—or even permitted—to question, reinterpret, or expand upon the knowledge presented to them.

This tightly controlled learning environment causes students to lose touch with their individual intellectual identity. The system does not provide sufficient opportunities, time, or structured programmes for students to reflect upon, explore, and rediscover their own sense of self, interests, and aspirations within their chosen disciplines. Instead of fostering thinkers, innovators, and creators, the system molds students into passive recipients of knowledge, trained to conform rather than lead or challenge.

This process ultimately produces what can be described as intellectual laborers or academic slaves—individuals who possess qualifications but lack the mastery, confidence, and creative agency required to meaningfully contribute to the evolution of their fields.

Lessons from history: How true masters emerged

Throughout history, true Masters in various fields have always been exceptional for reasons beyond the traditional boundaries of formal education. These individuals achieved greatness not because they followed prescribed curricula or sought the approval of educational institutions, but because they followed their inner callings with discipline, passion, and unwavering commitment.

What made these individuals exceptional wasn’t their adherence to rigid academic structures, but their pursuit of something much more profound: their innate talents and passions. They were able to innovate and push boundaries because they were free to follow what truly excited them, and their journeys were characterized by a level of self-driven discipline that the conventional education system often overlooks.

The inner call: Rediscovering lost pathways

Every person is born with a unique genetic and psychological blueprint — a natural inclination towards certain interests, talents, and callings. Recognising and following this ‘inner call’ gives meaning, strength, and resilience to individuals, enabling them to endure hardships, face failures, and persist through challenges.

However, when this call is lost or ignored, frustration and dissatisfaction take hold. Many young undergraduates today are victims of this disconnection. They follow paths chosen by parents, teachers, or society, without ever discovering their own. This is a tragedy we must urgently address.

According to my experience, a significant portion of students in almost every degree programme lack genuine interest in the field they have been placed in. Many of them quietly carry the sense that somewhere along the way, they have lost their direction—not because of a lack of ability, but because the educational journey they embarked on was shaped more by examination results, societal expectations, and external pressures than by their own inner desires.

Without real, personal interest in what they are studying, can we expect them to learn passionately, innovate boldly, or commit themselves fully? The answer is no. True mastery, creativity, and excellence can only emerge when learning is driven by genuine curiosity and an inner calling.

A new paradigm: Recognizing potential from the start

I envision a transformative educational approach where each student is recognized as a potential Master in their own right. From the very beginning of their journey, every new student should undergo a comprehensive interview process designed to uncover their true interests and passions.

This initiative will not only identify but nurture these passions. Students should be guided and mentored to develop into Masters in their chosen fields—be it entrepreneurship, sports, the arts, or any other domain. By aligning education with their innate talents, we empower students to excel and innovate, becoming leaders and pioneers in their respective areas.

Rather than a standardised intake or mere placement based on test scores or academic history, this new model would involve a holistic process, assessing academic abilities, personal passions, experiences, and the driving forces that define them as individuals.

Fostering Mastery through Mentorship and Guidance

Once students’ passions are identified, the next step is to help them develop these areas into true expertise. This is where mentorship becomes central. Students will work closely with professors, industry leaders, and experts in their chosen fields, ensuring their academic journey is as much about guidance and personal development as it is about gaining knowledge.

Mentors will play an instrumental role in refining students’ ideas, pushing the boundaries of their creativity, and fostering a mindset of continuous improvement. Through personalized guidance and structured support, students will take ownership of their learning, receiving real-world exposure, practical opportunities, and building the resilience and entrepreneurial spirit that drives Masters to the top of their fields.

Revolutionising the role of universities

This initiative will redefine the role of universities, transforming them from institutions of rote learning to dynamic incubators of creativity and mastery. Universities will no longer simply be places where students learn facts and figures—they will become vibrant ecosystems where students are nurtured and empowered to become experts and pioneers.

Rather than focusing solely on academic metrics, universities will measure success by real-world impact: startups launched, innovative works produced, research leading to social change. These will be the true indicators of success for a university dedicated to fostering Masters.

Empowering a generation of leaders and innovators

The result would be a generation of empowered individuals—leaders, thinkers, and doers ready to make a lasting impact. With mastery and passion-driven learning, these students will be prepared not just to fit into the world, but to change it. They will possess the skills, mindset, and confidence to innovate, disrupt, and lead across fields.

By aligning education with unique talents, we help students realize their potential and give them the tools to make their visions a reality. This is not about creating mere graduates—it’s about fostering true Masters.

Concluding remarks: A new path forward

The time has come to build a new kind of education—one that sees the potential for mastery in every undergraduate and actively nurtures that potential from the start. By prioritizing the passions and talents of students, we can create a future where individuals are not just educated, but truly empowered to become Masters of their craft.

In the crucial first weeks of university life, it is essential to create a supportive environment that recognizes the individuality of each student. To achieve this, we propose a structured process where students are individually interviewed by trained academic and counseling staff. These interviews will aim to uncover each student’s inner inclination, personal interests, and natural talents — what might be described as their “inner calling.”

Understanding a student’s deeper motivations and aspirations early in their academic journey can play a decisive role in shaping not only their academic choices but also their personal and professional development. This process will allow us to go beyond surface-level academic placement and engage students in disciplines and activities that resonate with their authentic selves.

At present, while many universities assign mentors to students, this system often remains underutilized and lacks proper structure. One of the main shortcomings is that lecturers and assigned mentors typically have not received specialized training in career guidance, psychological counseling, or interest-based mentoring. As a result, mentorship programs fail to provide personalized and meaningful guidance.

To address the disconnect between academic achievement and personal fulfillment in our universities, we propose a comprehensive, personalized guidance program for every student, starting with in-depth interviews and assessments to uncover their interests, strengths, and aspirations. Trained and certified mentors would then work closely with students to design personalized academic and personal development plans, aligning study paths, extracurricular activities, internships, and community engagements with each student’s inner calling.

Through continuous mentoring, regular feedback, and integration with university services such as career guidance, research groups, and industry collaborations, this program would foster a culture where students actively shape their futures. Regular evaluations and data-driven improvements would ensure the program’s relevance and effectiveness, ultimately producing well-rounded, fulfilled graduates equipped to lead meaningful, socially impactful lives.

by Senior Prof. E.P.S. Chandana

(Former Deputy Vice Chancellor/University of Ruhuna)

Faculty of Technology, University of Ruhuna

Midweek Review

Life of the Buddha

A Review of Rajendra Alwis’s book ‘Siddhartha Gauthama’

Gautama Buddha has been such a towering figure for over twenty six centuries of human history that there is no shortage of authors attempting to put together his life story cast as that of a supernatural being. Asvaghosa’s “Buddhacharita” appeared in the 1st century in Sanskrit. It is the story as narrated in the Lalitavisture Sutra that became translated into Chinese during the Jin and Tang dynasties, and inspired the art and sculpture of Gandhara and Barobudur. Tenzin Chogyel’s 18th century work Life of the Lord Victor Shakyamuni, Ornament of One Thousand Lamps for the Fortunate Eon is still a Penguin classic (as translated by R. Schaeffer from Tibetan).

Interestingly, there is no “Life of the Buddha” in Pali itself (if we discount Buddhagosha’s Kathavatthu), and the “thus have I heard” sutta’s of Bhikku Ananada, the personal assistant to the Buddha, contain only a minimal emphasis on the life of the Buddha directly. This was entirely in keeping with the Buddha’s exhortation to each one to minimize one’s sense of “self ” to the point of extinction.

However, it is inescapable that the life of a great teacher will be chronicled by his followers. Today, there is even a collective effort by a group of scholars who work within the “Buddha Sutra project”, aimed at presenting the Buddha’s life and teachings in English from a perspective grounded in the original Pali texts. The project, involving various international scholars of several traditions contribute different viewpoints and interpretations.

In contrast, there are the well-known individual scholarly studies, varying from the classic work of E. J. Thomas entitled “The Life of the Buddha according to the Pali Canon”, the very comprehensive accounts by Bhikku Nanamoli, or the scholarly work of John Strong that attempts to balance the historical narrative with the supernatural, canonical with the vernacular [1]. Furthermore, a vast variety of books in English cover even the sociological and cultural background related to the Buddha’s life within fictionalised approaches and via fact-seeking narratives. The classic work “Siddhartha” by Hermann Hesse, or the very recent “Mansions of the Moon”, by Shyam Selvadurai attempts to depict the daily life of Siddartha in the fifth century BCE in fictional settings. Interpretive narratives such as “The man who understood suffering” by Pankaj Misra provide another perspective on the Buddha and his times. In fact, a cursory search in a public library in Ontario, Canada came up with more than a dozen different books, and as many video presentations, in response to the search for the key-word “Life of the Buddha”.

Interestingly, a simple non-exhaustive search for books in Sinhala on “The Life of the Buddha” brings out some 39 books, but most of the content is restricted to a narrow re-rendering of the usual story that we learn from the well-known books by Bhikku Narada, or Ven. Kotagama Vachissra, while others are hagiographic and cover even the legendary life of Deepankara Buddha who, according to traditional belief, lived some hundred thousand eons (“kalpa”) ago!

However, as far as I know, there are hardly any books in Sinhala that attempt to discuss the sociological and cultural characteristics of the life and times of the Buddha, or discuss how an age of inquisitiveness and search for answers to fundamental philosophic questions developed in north Indian city states of the Magadha, Anga and Vajji regions that bracketed the River Ganges. In fact, Prof. Price, writing a preface to K. N. Jayatilleke’ s book on the Early Buddhist Theory of Knowledge states that the intellectual ambiance and the epistemological stance of the Buddha’s times could have been that of 1920s Cambridge when Bertrand Russell, Wittgenstein and others set the pace! A similar intellectual ambiance of open-minded inquiry regarding existential questions existed in the golden age of Greece, with philosophers like Heraclitus, Socrates and others who were surely influenced by the ebb and flow of ideas from India to the West, via the silk route that passed through Varanasi (Baranes Nuvara of Sinhalese Buddhist texts). The Buddha had strategically chosen Varanasi, le carrefour of the East-West and North-South silk routes, to deliver his first sermon to his earliest disciples.

This usual narrowness found in the books on the “Life of the Buddha” available in Sinhala is to some extent bridged by the appearance of the book “Siddhartha Gauthama- Shakya Muneendrayano” (Sarasavi Publishers, 2024) [2] written by Rajendra Alwis, an educationist and linguist holding post-graduate degrees from Universities in the UK and Canada. The book comes with an introduction by Dharmasena Hettiarchchi. well known for his writings on Buddhist Economic thought. Rajendra Alwis devotes the first four chapters of his book to a discussion of the socio-cultural and agricultural background that prevailed in ancient India. He attempts to frame the rise of Buddhist thought in the Southern Bihar region of India with the rise of a “rice-eating” civilisation that had the leisure and prosperity for intellectual discourse on existentialist matters.

The chapter on Brahminic traditions and the type of education received by upper caste children of the era is of some interest since some Indian and Western writers have even made the mistake of stating that the Buddha had no formal education. Rajendra Alwis occasionally weaves into his text quotations from the Sinhala Sandesha Kavya, etc., to buttress his arguments, and nicely blends Sinhalese literature into the narrative.

However, this discussion, or possibly an additional chapter, could have branched into a critical discussion of the teachings of the leading Indian thinkers of the era, both within the Jain and the Vedic traditions of the period. The systematisation of Parkrit languages into a synthetic linguistic form, viz., Sanskrit, in the hands of Panini and other Scholars took place during and overarching this same era. So, a lot of mind-boggling achievements took place during the Buddha’s time, and I for one would have liked to see these mentioned and juxtaposed within the context of what one might call the Enlightenment of the Ancient world that took place in the 6th Century BCE in India. Another lacuna in the book, hopefully to be rectified in a future edition, is the lack of a map, showing the cities and kingdoms that hosted the rise of this enlightenment during the times of Gautama Buddha and Mahaveera.

The treatment of the Buddha’s life is always a delicate task, especially when writing in Sinhala, in a context where the Buddha is traditionally presented as a superhuman person – Lord Buddha – even above and beyond all the devas. Rajendra Alwis has managed the tight-rope walk and discussed delicate issues and controversial events in the Buddha’s life, without the slightest sign of disrespect, or without introducing too much speculation of his own into events where nothing is accurately known. We need more books of this genre for the the Sinhala-reading public.

[1] See review by McGill University scholar Jessica Main: https://networks.h-net.org/node/6060/reviews/15976/main-strong-buddha-short-biography

[2] https://www.sarasavi.lk/product/siddhartha-gauthama-shakyamunidrayano-9553131948

By Chandre Dharmawardana

chandre.dharma@yahoo.ca

-

Business5 days ago

Business5 days agoAitken Spence Travels continues its leadership as the only Travelife-Certified DMC in Sri Lanka

-

Latest News4 days ago

Latest News4 days agoNPP win Maharagama Urban Council

-

Business5 days ago

Business5 days agoLinearSix and InsureMO® expand partnership

-

Business3 days ago

Business3 days agoJohn Keells Properties and MullenLowe unveil “Minutes Away”

-

Foreign News1 day ago

Foreign News1 day agoMexico sues Google over ‘Gulf of America’ name change

-

Business4 days ago

Business4 days agoNDB Bank partners with Bishop’s College to launch NDB Pixel awareness

-

Sports4 days ago

Sports4 days agoDamsiluni, Buwindu win Under 14 tennis titles

-

Business4 days ago

Business4 days agoHayleys debenture issue oversubscribed on opening day