Features

EARLY CAREER AND LONDON DEGREE

CHAPTER 8

I cannot say why I specialized in Banking and Currency – I think it was a hunch and perhaps literature was more readily available in Ceylon. (From an undated document (c.1950) in N.U. Jayawardena Personal Files. NU seemed to have an instinct for perceiving things that would become important in the economic and commercial development of Sri Lanka, as persons who watched his career over the years would observe. This would be only the first of such “hunches.”)

(N.U. Jayawardena reminiscing in the 1950s on why he selected this subject for his B.Sc. (Econ.) degree in 1931)

The 1930s were transitional years in NU’s career, when he added to his academic knowledge of economics in its practical and operational aspects. During this period, his abilities were recognized by persons of standing under whom he worked. This helped greatly in his development. What is more, his marriage gave him a certain degree of financial security and a congenial environment in which, while employed, to pursue his studies. NU in later years, often spoke with deep gratitude of the support and encouragement that his wife Gertrude gave him in his studies.

NU, even after entering the Clerical Service, did not relinquish hopes of studying for a degree. The circumstances in which he realized them were in part accidental. Shortly after he passed the London Matriculation in the First Division, he received a letter from Wolsey Hall, the well-known Correspondence College in Britain, enclosing a prospectus of study for degrees including the B.Sc. Economics. It also suggested that a knowledge of economics was greatly advantageous for public servants, especially those in colonial countries. Spurred on by this letter, NU registered for the course while working as a clerk. According to NU, if not for the Wolsey Hall letter, he never would have thought of studying economics. He had always wanted to be a doctor or lawyer but could only aspire to the clerical service. The letter from Wolsey Hall placed him on a path that would take him to heights far beyond what he then could have imagined.

Wolsey Hall, Oxford, was founded by J. William Knipe in 1894, at a time when access to a higher education – which had been largely the preserve of the elite – was beginning to become more widely available to other classes in society. Catering to this increasing demand

for education, Wolsey Hall offered tuition by correspondence for British university degrees and other examinations, especially for persons holding jobs, as well as others unable to study on campus for one reason or other. It also was a great boon for those in the colonies who wanted to qualify through external studies. Such correspondence courses and external examinations were a type of social revolution, which gave those who were poor and underprivileged, the chance for a higher education.

After four years, while working as a clerk in the Public Works Department, NU completed his B.Sc. (Econ.) degree. The degree was divided into the Intermediate, Parts I & II, and the Finals. Parts I & II included Economics, Economic History, British Constitution, Geography, Mathematics, Logic, and a language (French or German). ( According to notes in his Personal Files, NU studied both German and French. As part of its course requirements, the LSE required B.Sc. (Econ.) candidates to learn one of the two languages. The 1930 Calendar of the LSE B.Sc. (Econ.) stated that the Intermediate Part I examination would require candidates to read from works in either French, German and Italian and that they would pass the examination only if they proved able to read “with intelligence” French or German or Italian. NU’s grounding in Latin would certainly have helped him in learning French and German.) The final part consisted of Economics, Banking and Currency,

Economic History, English Law, and Statistics. Several months after his final examination in June 1931, NU was informed by Wolsey Hall that he had passed with Second Class Honours and that he was the only overseas candidate to be awarded an honours degree at the External B.Sc. (Econ.) examination. (Letter from the Registrar of Wolsey Hall, dated 11 November 1931 (N.U. Jayawardena Personal Files). NU now was also the only person in the Ceylon Clerical Services to hold a B.Sc. (Econ.) degree.

Aiming for a Higher Degree

NU’s desire for higher education did not end with this achievement. Even before he received his results, he made direct inquiries to London University about the possibility of doing externally a Masters degree in Economics from the London School of Economics (LSE). He began correspondence with some of its lecturers about the courses available and the required reading. He wrote to the Advisory Service for External Students of the University of London, and registered for the postgraduate M.Sc. (Econ.) degree in 1931.

At the same time, NU asked the local Director of Education in Sri Lanka, to inquire if this examination could be held locally, a request that was eventually granted. NU also asked for written course material. This, he was told, was not possible, but the University Correspondence College could provide the services of a tutor to help devise a list of course material, that would cost 7 shillings an hour, with a minimum fee for 4 hours. NU scribbled in the margin of this letter, “too expensive!”

Copious correspondence followed between NU and the University to decide on both his general and special subjects. In the end, NU and his LSE advisor settled on “Organisation of Monetary and Banking Institutions” as his general subject, and significantly, “Central Banks” as his special subject. It is remarkable that NU should have chosen Central Banks as a special subject, given the relatively undeveloped banking sector existing at that time in Sri Lanka.

The cost of books and the difficulties in securing them were a hurdle.( In a letter to his father-in-law, NU estimated the cost for the required books to be Rs.125 (N.U. Jayawardena Personal Files). His LSE advisor probably mistook NU’s delay in resolving this dilemma as indecision on his part. A letter from the External Department conveys what his advisor felt about NU’s interminable inquiries:

This student appears to be asking innumerable questions to postpone making up his own mind. I sympathize with the very real difficulty he must have in procuring books, but he must face the facts and realize that the M.Sc. Examination… must necessarily call for more intensive reading.

Not to be beaten, NU inquired about borrowing books from the University Library, but was told that it was against the rules for books to be sent out of Britain. Many important economic works were written in French or German, and according to his advisor, few translations were available. In deciding which subjects would be the most feasible for an external student, his advisor observed that:

The General subject of the ‘Organisation of Monetary and Banking Institutions’ with ‘Central Banks’ as a special subject would offer certainadvantages in the way of available literature.

Among the subjects available, he suggested that “Monetary Theory… might be of greater practical value to a person engaged in Government Service.”( Letter from the Secretary of the LSE External Department to NU, dated 12 September 1932 (N.U. Jayawardena Personal Files).

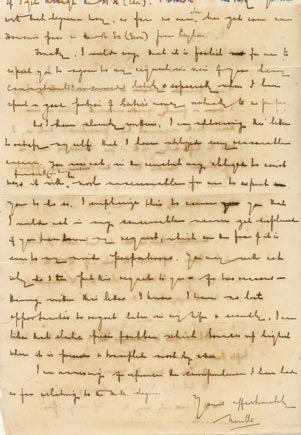

NU persisted in trying to find the means to pursue his goal. In December 1931, in a moving four-page letter, he turned to his father- in-law for financial assistance. He did so “with a certain amount of diffidence.” There were three things, he wrote, that made for success in the examination: “a good brain; a strong will and money to carry on the studies.” “I believe,” he added, “I have got the first two, but am lacking the third.” NU estimated the cost of the M.Sc. (Econ.) to be a total of Rs. 548, and added that he would only be able to bear some of the cost if he got “a better appointment,” or if rubber prices improved, enabling “us to get something from the estate,” which was part of his marriage settlement. He added that, if successful in the M.Sc. (Econ.) examination, he would be “the only Ceylonese with that degree.

” He ended the letter, disarmingly, saying he would understand if his “preposterous” request was turned down, but reasoned why he had to make this request. It was to ensure that he would have “no lost opportunities to regret later in my life,” and because, in his own words: “I am like that elastic piece of rubber which bounces up highest when it is pressed and trampled most” (Letter to Norman Wickramasinghe, 19 Dec. 1931). These last words would prove to be prescient. NU’s request was granted, and his letter returned to him with the emphatic words: “I would gladly comply with your wishes to enable you to take up the higher exam!” written in blue pencil at the top of the letter. However, for reasons unknown, NU did not take up his studies.

From his protracted correspondence with the university, it appears that he had managed to postpone the examination until 1935. He was, in fact, compelled to do so. Rubber prices had crashed in the early 1930s, and much of his father-in-law’s wealth came from his holdings in rubber. Two other factors may have contributed to his decision. One was an increasing workload, especially connected with the Banking Commission of 1934 (see Chapter 9); and the other was the births of his sons, Lalith (Lal) in 1934 and Nimal in 1936. However, NU’s ambition to continue his studies would be realized in 1938, when he was given a scholarship to attend the London School of Economics (LSE) to study Business Administration.

Early Interest in Central Banking

Even though NU did not formally study for the M.Sc. (Econ.) degree, it is interesting to take note of the advice and reading list his advisor had sent and the latter’s comments about Central Banking, which was a newly emerging area of study at the time (Letter from the Secretary of the LSE External Department to NU, dated 12 September 1932 (N.U. Jayawardena Personal Files).

Central Banking policy is in the centre of modern theoretical discussions, and acquaintance with and understanding of these is essential for the candidate. Keynes’ Treatise and Hayek’s Prices and Production are perhaps the most important recent contributions. (N.U. Jayawardena personal files)

NU was also advised that, “in the study of modern central banks” he should “concentrate chiefly on England, USA, Germany and France,” but to also give some attention “to other countries… where the organization of commercial banks is less developed – and to countries which have at present no central bank but are thinking of establishing one” (Letter from the Secretary of the LSE External Department to NU, dated 12 September 1932 (N.U. Jayawardena Personal Files).).

The exhaustive reading list sent by the advisor for the degree included documents and books on central banking in England, France, Germany and the United States. For the United States he recommended studying the annual reports of the Federal Reserve Board, as well as the Senate Banking and Currency Subcommittee report covering the operation of the national and Federal Reserve banking systems. He also advised him to read the Economist magazine, to “keep abreast of current events” (Letter from the Secretary of the LSE External Department to NU, dated 12 September 1932 (N.U. Jayawardena Personal Files). This NU was to do inhis later years, also ordering the Economist Diary annually.

For a full-time internal student, the requirements for a London M.Sc. were daunting enough. Textbooks were rare at the time, and LSE students – according to one of them – had to study “an enormous number of primary sources, books and articles” (B.K. Nehru, quoted in Dahrendorf, 1995, p.190). Works also had to be read in their original languages. For an external student separated by distance, with no direct access to specialist libraries and tutors, one can only imagine how much more daunting the challenge would have been.

It is interesting to speculate that NU, who seized every opportunity and tenaciously pursued his goals, may have begun to acquaint himself with some of these recommended works, even after he was unable to take up his M.Sc. (Econ.) studies. In this context, one can better appreciate why NU often said with much pride throughout his life, “if to be educated means to be taught, then I am an uneducated man.”

Temporary Disappointments

With his degree in Economics, NU had applied for posts in which he could put his newly acquired knowledge into use. A letter of recommendation written in January 1932 by the Director of Public Works, H.B. Lees, sums up NU’s qualities at this point in time:

Mr. Jayawardena is a very promising officer and has by his own exertions succeeded in obtaining by private study good academic qualifications in Economics… He has carried out his duties… with marked efficiency and

conscientiousness… his conduct… has been exemplary. (N.U. Jayawardena personal files)

NU first applied for the post of Probationary Assessor in the Department of Inland Revenue and was interviewed by J. H. Huxham, who a few years later became the Financial Secretary. Unfortunately, NU was not selected. He then applied for the post of Assistant Accountant in the Labour Department. Here again he was not taken, apparently due to his lack of accountancy qualifications. These failures, far from discouraging him, made him more determined to press on. Apparently, during this period he took a correspondence course in Accountancy from Bennett College in Sheffield, England and “served… [his] articles under N. Sabamoorthy, an Indian who had an office in Sea Street” (N.U. Jayawardena, interviewed by”Eriq,” The Island, 25 Feb. 1998).

Constitutional Reforms and New Vistas for NU

The political situation in the country had moved forward with the Donoughmore Reforms, and the first general election was held under universal franchise in 1931. These reforms provided the country with a greater degree of autonomy and training towards self-governance and democracy. Under the Donoughmore Constitution, a “State Council” (as the legislature was known) was set up. It was composed of 50 elected members and 6 members nominated to represent minorities and special interests. There were also three “Officers of State,” the Financial Secretary, the Legal Secretary and the Chief Secretary – all British – and a Governor, with controlling powers. Each State Council member was assigned to one of seven committees, chaired by a Minister.

Several capable and dedicated Sri Lankans were selected as Ministers, including Peri Sunderam, who was the first Minister of Labour, Industries and Commerce. Peri Sunderam recognized NU’s capabilities, and over the next several years, provided him the opportunities

to apply his knowledge and to excel. Like NU, Peri Sunderam had also risen from humble origins. He had his secondary education at Trinity College, Kandy, then graduated from Cambridge University, and also qualified as a barrister in London. After returning to Sri Lanka, he won the Hatton seat, uncontested in the State Council, in the election of 1931. As Minister, he scouted for intelligent persons for his Ministry. Although NU’s application to the Labour Department had been turned down, Peri Sunderam took note of his qualifications and wanted NU at the Registrar General’s Office, which was under his Ministry. NU was transferred there in July 1932.

The Commercial Intelligence Unit

The Ministry of Labour, Industries and Commerce would be the initial training ground for NU during the 1930s and the first few years of the 1940s. The varying capacities in which he served over this period provided him with many opportunities to develop a solid grounding in commercial activities, trade, administrative and banking matters. In his work, he displayed his usual perseverance and industry. Peri Sunderam, who served as Labour Minister from 1931 to 1936, recognized the need to strengthen trade links with India. In 1932 he led the first Ceylon Government Delegation to attend the Annual Sessions of the Chamber of Industries in New Delhi, and took NU and a civil servant with him. This was NU’s first trip abroad. On his return, he reported on the need for a commercial intelligence agency.

During this period, NU served under L.J.B. Turner, who was the Registrar General. Turner was in the process of setting up a Commercial Intelligence Unit within the Ministry. Peri Sunderam suggested that NU be assigned to write up the report. On the basis of the recommendations that NU made in his report, the new unit was set up. NU was full of admiration for Turner, whom he described as “a fine civil servant,” from whom he learnt “the necessity of being terse in language, the importance of accuracy, to never print any statistic without double checking and dating all papers and correspondence” (Roshan Pieris, 1988). Turner, it may be noted, who had been in charge of the Census of 1921 and had analysed the data and authored the Report.

Turner was succeeded by J.C.W. Rock as Registrar General, who acknowledged NU’s contribution to setting up the new department. Rock stated in 1943: “N.U. Jayawardena… and two clerks formed the nucleus from which the present Department has developed and

it was he who assisted me throughout in shaping its design and

growth” (N.U. Jayawardena Personal Files).

NU, who had not only worked on the report on the Commercial Intelligence Unit, but had also advised on its creation and organization, had hoped to be appointed Assistant Director of the new unit. Much to NU’s disappointment, E.C. Paul, a barrister, was appointed instead. NU, determined to move forward, applied for other posts. On 6 September 1933, Rock wrote a letter of recommendation for NU, whom he said “possesses ability above the average and has a well-formed grasp of economic problems,” adding, “I am sorry to be losing him” (N.U. Jayawardena Personal Files).

However, NU remained in the department and, a short time later, at the age of 26 in November 1934, was promoted to the post of Commercial Assistant to J.C.W. Rock. His new duties included finding markets abroad for local products, making trade investigations, dealing with changes in tariffs and trade agreements, and supplying commercial intelligence – in short, to look after the interests of Sri Lankan trade. The Sri Lankan government at this time had two trade commissioners abroad, in London and in Bombay. The Department of Commerce functioned on the lines of the Department of Overseas Trade in the UK (N.U. Jayawardena Personal Files). NU held this post until 1942. In assessing NU’s performance

as his assistant, in 1938, Rock noted that:

[NU] has acquired a very thorough knowledge of the trade and the industries of Ceylon… [and] has a sound knowledge of economics, both in its theoretical and applied aspects, and he has been of the greatest assistance

to me in carrying out the work of this Department… [He] has shown a high degree of industry, initiative and executive ability. His work is of a character requiring considerable research. (J.C.W. Rock, recommendation

dated 30 March 1938)

Shortly before his promotion, NU was to receive an even bigger break – enabling him to gain a comprehensive overview of the existing problems in banking and credit in Sri Lanka. This landmark event was his appointment by Peri Sunderam in April 1934 to the Banking Commission as its Assistant Secretary. The Commission was established to examine the deficiencies in the island’s banking system. His work in the Commission would not only provide NU with insights into the economic realities of Sri Lanka in the 1930s, but also propel his career forward. (N.U. JAYAWARDENA The First Five Decades Chapter 7 can read online on )

(Excerpted from N.U. JAYAWARDENA The first five decades)

By Kumari Jayawardena and Jennifer Moragoda ✍️

Features

Zelensky tells BBC Putin has started World War 3 and must be stopped

Ukraine’s President Volodymyr Zelensky continues to send out a firm message of defiance.

When we met this weekend in the government headquarters in Kyiv, he said that far from losing, Ukraine would end the war victorious. He was firmly against paying the price for a ceasefire deal demanded by President Vladimir Putin, which is withdrawing from strategic ground that Russia has failed to capture despite sacrificing tens of thousands of soldiers.

Putin, Zelensky said, has already started World War Three, and the only answer was intense military and economic pressure to force him to step back.

“I believe that Putin has already started it. The question is how much territory he will be able to seize and how to stop him… Russia wants to impose on the world a different way of life and change the lives people have chosen for themselves.”

What about Russia’s demand for Ukraine to hand over the 20% of the eastern region of Donetsk that it still holds – a line of towns Ukraine calls “fortress cities” – as well as more land in the southern regions of Kherson and Zaporizhzhia? Isn’t that, I asked, a reasonable request if it produces a ceasefire?

“I see this differently. I don’t look at it simply as land. I see it as abandonment – weakening our positions, abandoning hundreds of thousands of our people who live there. That is how I see it. And I am sure that this ‘withdrawal’ would divide our society.”

But isn’t it a good price to pay if that satisfies President Putin? Do you think it would satisfy him?

“It would probably satisfy him for a while… he needs a pause… but once he recovers, our European partners say it could take three to five years. In my opinion, he could recover in no more than a couple of years. Where would he go next? We do not know, but that he would want to continue the war is a fact.”

I met Volodymyr Zelensky in a conference room inside the heavily-guarded government enclave in a well-to-do corner of central Kyiv. In the interview he spoke mostly in Ukrainian.

You get a sense of the weight of leadership carried by Zelensky from the diligence of his security guards.

Visiting any head of state requires rigorous checks. But entering the presidential buildings in Kyiv takes the process to a level I have rarely experienced before.

It is not surprising in a country at war, with a president who has already been targeted by Russia.

Despite all that, the man who started as an entertainer, who won the Ukrainian version of Strictly Come Dancing in 2006, and played the role of an unexpected president of Ukraine in a TV comedy, before becoming the real-life president of Ukraine, seems to be remarkably resilient.

US President Donald Trump said on the eve of the most recent ceasefire talks in Geneva that “Ukraine better come to the table fast”.

He continues to default to putting more pressure on Ukraine than on Russia.

Western diplomats have indicated since last summer that Trump agrees with Putin that territorial concessions from Ukraine to Russia are the key to the ceasefire Trump wants, ideally before this coming summer.

Plenty of analysts outside the White House also judge that Ukraine cannot win the war and, without making concessions to Moscow, will lose it.

I asked Zelensky whether Trump and the others had a point.

“Where are you now?” Zelensky asked in return. “Today you are in Kyiv, you are in the capital of our homeland, you are in Ukraine. I am very grateful for this. Will we lose? Of course not, because we are fighting for Ukraine’s independence.”

Zelensky has often said that Ukraine can win, but what would victory look like?

Of course, he said, victory meant restoring normal lives for Ukrainians and ending the killing. But the wider view of victory he presented was all about a global threat that he says comes from Putin.

“I believe that stopping Putin today and preventing him from occupying Ukraine is a victory for the whole world. Because Putin will not stop at Ukraine.”

You are not saying that victory is getting all the land back, are you?

“We’ll do it. That is absolutely clear. It is only a matter of time. To do it today would mean losing a huge number of people – millions of people – because the [Russian] army is large, and we understand the cost of such steps. You would not have enough people, you would be losing them. And what is land without people? Honestly, nothing.”

“And we also don’t have enough weapons. That depends not just on us, but on our partners. So as of now that’s not possible but returning to the just borders of 1991 [the year Ukraine declared its independence, precipitating the final collapse of the Soviet Union] without a doubt, is not only a victory, it’s justice. Ukraine’s victory is the preservation of our independence, and a victory of justice for the whole world is the return of all our lands.”

A year ago, Zelensky visited the White House and received a reception one senior Western diplomat described to me as a pre-planned public “diplomatic mugging” from Donald Trump and his Vice-President, JD Vance.

Their argument, in the presence of the world’s media, was watched by millions around the world.

Trump, just inaugurated as president for the second time, was sending the strongest possible signal that the era of support Zelensky and Ukraine had relied on from President Joe Biden was over. Nato members were already on notice from the new administration. Vance had just got back from shattering Western European illusions about the strength of the trans-Atlantic alliance.

Since then, reportedly coached by Britain’s National Security Adviser Jonathan Powell among others, Zelensky has avoided public confrontations with Trump.

The US president has stopped almost all shipments of military aid to Ukraine. But the US still provides vital intelligence, and European countries are spending billions buying weapons from the Americans to give to Ukraine.

I asked Ukraine’s president about Trump’s often contradictory statements, recalling that among the untruths he has uttered is the accusation that Zelensky is a dictator who started the war – a precise echo of claims made by Vladimir Putin.

Zelensky laughed.

“I am not a dictator, and I didn’t start the war, that’s it.”

But can you trust President Trump? If you extract a security guarantee from him, I asked, would he keep his word? He is after all a man who changes his mind.

“It is not only President Trump, we’re talking about America. We are all presidents for the appropriate terms. We want guarantees for 30 years for example. Political elites will change, leaders will change.”

He meant that US security guarantees needed approval from Congress in Washington DC to make them watertight.

“They will be voted on in Congress for a reason. It’s not just presidents. Congress is needed. Because the presidents change, but institutions stay.”

In other words, Donald Trump might be unreliable, but he will not be there for ever.

Zelensky says those security guarantees would have to be in place before he could consider another American demand – the US demand for Ukraine to hold a general election by the summer, echoing another Russian talking point that Zelensky is an illegitimate president. Trump has not demanded elections in Russia, where Putin became leader for the first time on the last day of the 20th Century.

Zelensky said he had not decided whether to stand again, whenever an election is held: “I might run and might not.”

Elections were due in 2024, but they could not be held under martial law that was introduced after Russia’s full-scale invasion.

Holding postponed elections, Zelensky said, was technically possible if they had time to change the law to allow them to happen. But he needed security guarantees for Ukraine first.

He went on to raise so many potential problems about holding an election with millions of Ukrainians abroad as refugees and significant tracts of the country occupied by Russia that I suggested that in reality he was against the idea.

“If this is a condition for ending the war, let’s do it. I said, ‘honestly, you constantly raise the issue of elections’. I told the partners, ‘you need to decide one thing: you want to get rid of me or you want to hold elections? If you want to hold elections, (even if you are not ready to tell me honestly even now), then hold these elections honestly. Hold them in a way that the Ukrainian people will recognise, first of all. And you yourself must recognise that these are legitimate elections'”.

Volodymyr Zelensky has opponents and harsh critics here in Ukraine.

His government was rocked last autumn by a corruption scandal that led to the departure of his closest adviser.

But Zelensky, with a new team, still commands approval ratings that most leaders in Western Europe can only dream about.

He has irritated his allies at times with constant demands for more and better equipment. One of the accusations directed at him in the Oval Office by Trump and Vance a year ago was that he was not sufficiently grateful.

The latest item on his list is permission to manufacture American weapons under licence, including Patriot air defence missiles.

“Today the issue is air defence. This is the most difficult problem. Unfortunately, our partners still do not grant licenses for us to produce systems ourselves, for example, Patriot systems, or even missiles for the systems we already have. So far, we have not achieved success in this.”

Why won’t they do that?

“I don’t know. I have no answer.”

At the end of the interview, he switched from Ukrainian to English.

Given everything he had said, I asked him whether we needed to get ready for an even longer war in Ukraine.

“No, no, no, it’s two parallel tracks… you are playing chess with a lot of leaders, not with Russia. There is not one right way. You have to choose a lot of parallel steps, parallel directions. And one of these parallel ways will, I think, bring success. For us, success is to stop Putin.”

But Vladimir Putin isn’t going to end this war, is he? Unless he’s under massive pressure and he doesn’t seem to be.

“Yes and no. We will see. Yes and no. He doesn’t want, but doesn’t want doesn’t mean he will not. God bless. God bless, we will be successful. Thank you.”

And with that, he posed for photographs, shook hands with the BBC team, and strode out of the room.

[BBC]

Features

Reconciliation, Mood of the Nation and the NPP Government

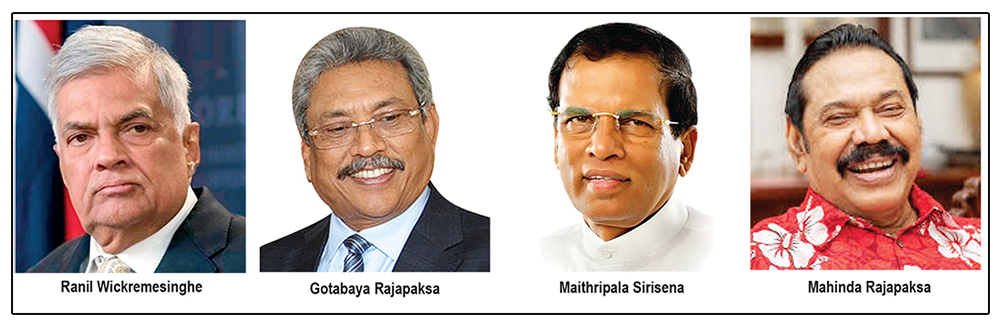

From the time the search for reconciliation began after the end of the war in 2009 and before the NPP’s victories at the presidential election and the parliamentary election in 2024, there have been four presidents and four governments who variously engaged with the task of reconciliation. From last to first, they were Ranil Wickremesinghe, Gotabaya Rajapaksa, Maithripala Sirisena and Mahinda Rajapaksa. They had nothing in common between them except they were all different from President Anura Kumara Dissanayake and his approach to reconciliation.

The four former presidents approached the problem in the top-down direction, whereas AKD is championing the building-up approach – starting from the grassroots and spreading the message and the marches more laterally across communities. Mahinda Rajapaksa had his ‘agents’ among the Tamils and other minorities. Gotabaya Rajapaksa was the dummy agent for busybodies among the Sinhalese. Maithripala Sirisena and Ranil Wickremesinghe operated through the so called accredited representatives of the Tamils, the Muslims and the Malaiayaka (Indian) Tamils. But their operations did nothing for the strengthening of institutions at the provincial and the local levels. No did they bother about reaching out to the people.

As I recounted last week, the first and the only Northern Provincial Council election was held during the Mahinda Rajapaksa presidency. That nothing worthwhile came out of that Council was not mainly the fault of Mahinda Rajapaksa. His successors, Maithripala Sirisena and Ranil Wickremesinghe as Prime Minister, with the TNA acceding as a partner of their government, cancelled not only the NPC but also all PC elections and indefinitely suspended the functioning of the country’s nine elected provincial councils. Now there are no elected councils, only colonial-style governors and their secretaries.

Hold PC Elections Now

And the PC election can, like so many other inherited rotten cans, is before the NPP government. Is the NPP government going to play footsie with these elections or call them and be done with it? That is the question. Here are the cons and pros as I see them.

By delaying or postponing the PC elections President AKD and the NPP government are setting themselves up to be justifiably seen as following the cynical playbook of the former interim President Ranil Wickremesinghe. What is the point, it will be asked, in subjecting Ranil Wickremesinghe to police harassment over travel expenses while following his playbook in postponing elections?

Come to think of it, no VVIP anywhere can now whine of unfair police arrest after what happened to the disgraced former prince Andrew Mountbatten Windsor in England on Thursday. Good for the land where habeas corpus and due process were born. The King did not know what was happening to his kid brother, and he was wise enough to pronounce that “the law must take its course.” There is no course for the law in Trump’s America where Epstein spun his webs around rich and famous men and helpless teenage girls. Only cover up. Thanks to his Supreme Court, Trump can claim covering up to be a core function of his presidency, and therefore absolutely immune from prosecution. That is by the way.

Back to Sri Lanka, meddling with elections timing and process was the method of operations of previous governments. The NPP is supposed to change from the old ways and project a new way towards a Clean Sri Lanka built on social and ethical pillars. How does postponing elections square with the project of Clean Sri Lanka? That is the question that the government must be asking itself. The decision to hold PC elections should not be influenced by whether India is not asking for it or if Canada is requesting it.

Apart from it is the right thing do, it is also politically the smart thing to do.

The pros are aplenty for holding PC elections as soon it is practically possible for the Election Commission to hold them. Parliament can and must act to fill any legal loophole. The NPP’s political mojo is in the hustle and bustle of campaigning rather than in the sedentary business of governing. An election campaign will motivate the government to re-energize itself and reconnect with the people to regain momentum for the remainder of its term.

While it will not be possible to repeat the landslide miracle of the 2024 parliamentary election, the government can certainly hope and strive to either maintain or improve on its performance in the local government elections. The government is in a better position to test its chances now, before reaching the halfway mark of its first term in office than where it might be once past that mark.

The NPP can and must draw electoral confidence from the latest (February 2026) results of the Mood of the Nation poll conducted by Verité Research. The government should rate its chances higher than what any and all of the opposition parties would do with theirs. The Mood of the Nation is very positive not only for the NPP government but also about the way the people are thinking about the state of the country and its economy. The government’s approval rating is impressively high at 65% – up from 62% in February 2025 and way up from the lowly 24% that people thought of the Ranil-Rajapaksa government in July 2024. People’s mood is also encouragingly positive about the State of the Economy (57%, up from 35% and 28%); Economic Outlook (64%, up from 55% and 30%); the level of Satisfaction with the direction of the country( 59%, up from 46% and 17%).

These are positively encouraging numbers. Anyone familiar with North America will know that the general level of satisfaction has been abysmally low since the Iraq war and the great economic recession. The sour mood that invariably led to the election of Trump. Now the mood is sourer because of Trump and people in ever increasing numbers are looking for the light at the end of the Trump tunnel. As for Sri Lanka, the country has just come out of the 20-year long Rajapaksa-Ranil tunnel. The NPP represents the post Rajapaksa-Ranil era, and the people seem to be feeling damn good about it.

Of course, the pundits have pooh-poohed the opinion poll results. What else would you expect? You can imagine which twisted way the editorial keypads would have been pounded if the government’s approval rating had come under 50%, even 49.5%. There may have even been calls for the government to step down and get out. But the government has its approval rating at 65% – a level any government anywhere in the Trump-twisted world would be happy to exchange without tariffs. The political mood of the people is not unpalpable. Skeptical pundits and elites will have to only ask their drivers, gardeners and their retinue of domestics as to what they think of AKD, Sajith or Namal. Or they can ride a bus or take the train and check out the mood of fellow passengers. They will find Verité’s numbers are not at all far-fetched.

Confab Threats

The government’s plausible popularity and the opposition’s obvious weaknesses should be good enough reason for the government to have the PC elections sooner than later. A new election campaign will also provide the opportunity not only for the government but also for the opposition parties to push back on the looming threat of bad old communalism making a comeback. As reported last week, a “massive Sangha confab” is to be held at 2:00 PM on Friday, February 20th, at the All Ceylon Buddhist Congress Headquarters in Colombo, purportedly “to address alleged injustices among monks.”

According to a warning quote attributed to one of the organizers, Dambara Amila Thero, “never in the history of Sri Lanka has there been a government—elected by our own votes and the votes of the people—that has targeted and launched such systematic attacks against the entire Sasana as this one.” That is quite a mouthful and worthier practitioners of Buddhism have already criticized this unconvincing claim and its being the premise for a gathering of spuriously disaffected monks. It is not difficult to see the political impetus behind this confab.

The impetus obviously comes from washed up politicians who have tried every slogan from – L-board-economists, to constitutional dictatorship, to save-our children from sex-education fear mongering – to attack the NPP government and its credibility. They have not been able to stick any of that mud on the government. So, the old bandicoots are now trying to bring back the even older bogey of communalism on the pretext that the NPP government has somewhere, somehow, “targeted and launched such systematic attacks against the entire Sasana …”

By using a new election campaign to take on this threat, the government can turn the campaign into a positively educational outreach. That would be consistent with the President’s and the government’s commitment to “rebuild Sri Lanka” on the strength of national unity without allowing “division, racism, or extremism” to undermine unity. A potential election campaign that takes on the confab of extremists will also provide a forum and an opportunity for the opposition parties to let their positions known. There will of course be supporters of the confab monks, but hopefully they will be underwhelming and not overwhelming.

For all their shortcomings, Sajith Premadasa and Namal Rajapaksa belong to the same younger generation as Anura Kumara Dissanayake and they are unlikely to follow the footsteps of their fathers and fan the flames of communalism and extremism all over again. Campaigning against extremism need not and should not take the form of disparaging and deriding those who might be harbouring extremist views. Instead, the fight against extremism should be inclusive and not exclusive, should be positively educational and appeal to the broadest cross-section of people. That is the only sustainable way to fight extremism and weaken its impacts.

Provincial Councils and Reconciliation

In the framework of grand hopes and simple steps of reconciliation, provincial councils fall somewhere in between. They are part of the grand structure of the constitution but they are also usable instruments for achieving simple and practical goals. Obviously, the Northern Provincial Council assumes special significance in undertaking tasks associated with reconciliation. It is the only jurisdiction in the country where the Sri Lankan Tamils are able to mind their own business through their own representatives. All within an indivisibly united island country.

But people in the north will not be able to do anything unless there is a provincial council election and a newly elected council is established. If the NPP were to win a majority of seats in the next Northern Provincial Council that would be a historic achievement and a validation of its approach to national reconciliation. On the other hand, if the NPP fails to win a majority in the north, it will have the opportunity to demonstrate that it has the maturity to positively collaborate from the centre with a different provincial government in the north.

The Eastern Province is now home to all three ethnic groups and almost in equal proportions. Managing the Eastern Province will an experiential microcosm for managing the rest of the country. The NPP will have the opportunity to prove its mettle here – either as a governing party or as a responsible opposition party. The Central Province and the Badulla District in the Uva Province are where Malaiyaka Tamils have been able to reconstitute their citizenship credentials and exercise their voting rights with some meaningful consequence. For decades, the Malaiyaka Tamils were without voting rights. Now they can vote but there is no Council to vote for in the only province and district they predominantly leave. Is that fair?

In all the other six provinces, with the exception of the Greater Colombo Area in the Western Province and pockets of Muslim concentrations in the South, the Sinhalese predominate, and national politics is seamless with provincial politics. The overlap often leads to questions about the duplication in the PC system. Political duplication between national and provincial party organizations is real but can be avoided. But what is more important to avoid is the functional duplication between the central government in Colombo and the provincial councils. The NPP governments needs to develop a different a toolbox for dealing with the six provincial councils.

Indeed, each province regardless of the ethnic composition, has its own unique characteristics. They have long been ignored and smothered by the central bureaucracy. The provincial council system provides the framework for fostering the unique local characteristics and synthesizing them for national development. There is another dimension that could be of special relevance to the purpose of reconciliation.

And that is in the fostering of institutional partnerships and people to-people contacts between those in the North and East and those in the other Provinces. Linkages could be between schools, and between people in specific activities – such as farming, fishing and factory work. Such connections could be materialized through periodical visits, sharing of occupational challenges and experiences, and sports tournaments and ‘educational modules’ between schools. These interactions could become two-way secular pilgrimages supplementing the age old religious pilgrimages.

Historically, as Benedict Anderson discovered, secular pilgrimages have been an important part of nation building in many societies across the world. Read nation building as reconciliation in Sri Lanka. The NPP government with its grassroots prowess is well positioned to facilitate impactful secular pilgrimages. But for all that, there must be provincial councils elections first.

by Rajan Philips

Features

Barking up the wrong tree

The idiom “Barking up the wrong tree” means pursuing a mistaken line of thought, accusing the wrong person, or looking for solutions in the wrong place. It refers to hounds barking at a tree that their prey has already escaped from. This aptly describes the current misplaced blame for young people’s declining interest in religion, especially Buddhism.

It is a global phenomenon that young people are increasingly disengaged from organized religion, but this shift does not equate to total abandonment, many Gen Z and Millennials opt for individual, non-institutional spirituality over traditional structures. However, the circumstances surrounding Buddhism in Sri Lanka is an oddity compared to what goes on with religions in other countries. For example, the interest in Buddha Dhamma in the Western countries is growing, especially among the educated young. The outpouring of emotions along the 3,700 Km Peace March done by 16 Buddhist monks in USA is only one example.

There are good reasons for Gen Z and Millennials in Sri Lanka to be disinterested in Buddhism, but it is not an easy task for Baby Boomer or Baby Bust generations, those born before 1980, to grasp these bitter truths that cast doubt on tradition. The two most important reasons are: a) Sri Lankan Buddhism has drifted away from what the Buddha taught, and b) The Gen Z and Millennials tend to be more informed and better rational thinkers compared to older generations.

This is truly a tragic situation: what the Buddha taught is an advanced view of reality that is supremely suited for rational analyses, but historical circumstances have deprived the younger generations over centuries from knowing that truth. Those who are concerned about the future of Buddhism must endeavor to understand how we got here and take measures to bridge that information gap instead of trying to find fault with others. Both laity and clergy are victims of historical circumstances; but they have the power to shape the future.

First, it pays to understand how what the Buddha taught, or Dhamma, transformed into 13 plus schools of Buddhism found today. Based on eternal truths he discovered, the Buddha initiated a profound ethical and intellectual movement that fundamentally challenged the established religious, intellectual, and social structures of sixth-century BCE India. His movement represented a shift away from ritualistic, dogmatic, and hierarchical systems (Brahmanism) toward an empirical, self-reliant path focused on ethics, compassion, and liberation from suffering. When Buddhism spread to other countries, it transformed into different forms by absorbing and adopting the beliefs, rituals, and customs indigenous to such land; Buddha did not teach different truths, he taught one truth.

Sri Lankan Buddhism is not any different. There was resistance to the Buddha’s movement from Brahmins during his lifetime, but it intensified after his passing, which was responsible in part for the disappearance of Buddhism from its birthplace. Brahminism existed in Sri Lanka before the arrival of Buddhism, and the transformation of Buddhism under Brahminic influences is undeniable and it continues to date.

This transformation was additionally enabled by the significant challenges encountered by Buddhism during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries (Wachissara 1961, Mirando 1985). It is sad and difficult to accept, but Buddhism nearly disappeared from the land that committed the Teaching into writing for the first time. During these tough times, with no senior monks to perform ‘upasampada,’ quasi monks who had not been admitted to the order – Ganninanses, maintained the temples. Lacking any understanding of the doctrinal aspects of Buddha’s teaching, they started performing various rituals that Buddha himself rejected (Rahula 1956, Marasinghe 1974, Gombrich 1988, 1997, Obeyesekere 2018).

The agrarian population had no way of knowing or understanding the teachings of the Buddha to realize the difference. They wanted an easy path to salvation, some power to help overcome an illness, protect crops from pests or elements; as a result, the rituals including praying and giving offerings to various deities and spirits, a Brahminic practice that Buddha rejected in no uncertain terms, became established as part of Buddhism.

This incorporation of Brahminic practices was further strengthened by the ascent of Nayakkar princes to the throne of Kandy (1739–1815) who came from the Madurai Nayak dynasty in South India. Even though they converted to Buddhism, they did not have any understanding of the Teaching; they were educated and groomed by Brahminic gurus who opposed Buddhism. However, they had no trouble promoting the beliefs and rituals that were of Brahminic origin and supporting the institution that performed them. By the time British took over, nobody had any doubts that the beliefs, myths, and rituals of the Sinhala people were genuine aspects of Buddha’s teaching. The result is that today, Sri Lankan Buddhists dare doubt the status quo.

The inclusion of Buddhist literary work as historical facts in public education during the late nineteenth century Buddhist revival did not help either. Officially compelling generations of students to believe poetic embellishments as facts gave the impression that Buddhism is a ritualistic practice based on beliefs.

This did not create any conflict in the minds of 19th agrarian society; to them, having any doubts about the tradition was an unthinkable, unforgiving act. However, modernization of society, increased access to information, and promotion of rational thinking changed things. Younger generations have begun to see the futility of current practices and distance themselves from the traditional institution. In fact, they may have never heard of it, but they are following Buddha’s advice to Kalamas, instinctively. They cannot be blamed, instead, their rational thinking must be appreciated and promoted. It is the way the Buddha’s teaching, the eternal truth, is taught and practiced that needs adjustment.

The truths that Buddha discovered are eternal, but they have been interpreted in different ways over two and a half millennia to suit the prevailing status of the society. In this age, when science is considered the standard, the truth must be viewed from that angle. There is nothing wrong or to be afraid of about it for what the Buddha taught is not only highly scientific, but it is also ahead of science in dealing with human mind. It is time to think out of the box, instead of regurgitating exegesis meant for a bygone era.

For example, the Buddhist model of human cognition presented in the formula of Five Aggregates (pancakkhanda) provides solutions to the puzzles that modern neuroscience and philosophers are grappling with. It must be recognized that this formula deals with the way in which human mind gathers and analyzes information, which is the foundation of AI revolution. If the Gen Z and Millennial were introduced to these empirical aspects of Dhamma, they would develop a genuine interest in it. They thrive in that environment. Furthermore, knowing Buddha’s teaching this way has other benefits; they would find solutions to many problems they face today.

Buddha’s teaching is a way to understand nature and the humans place in it. One who understands this can lead a happy and prosperous life. As the Dhammapada verse number 160 states – “One, indeed, is one’s own refuge. Who else could be one’s own refuge?” – such a person does not depend on praying or offering to idols or unknown higher powers for salvation, the Brahminic practice. Therefore, it is time that all involved, clergy and laity, look inwards, and have the crucial discussion on how to educate the next generation if they wish to avoid Sri Lankan Buddhism suffer the same fate it did in India.

by Geewananda Gunawardana, Ph.D.

-

Features23 hours ago

Features23 hours agoWhy does the state threaten Its people with yet another anti-terror law?

-

Business7 days ago

Business7 days agoMinistry of Brands to launch Sri Lanka’s first off-price retail destination

-

Features23 hours ago

Features23 hours agoVictor Melder turns 90: Railwayman and bibliophile extraordinary

-

Features23 hours ago

Features23 hours agoReconciliation, Mood of the Nation and the NPP Government

-

Latest News2 days ago

Latest News2 days agoNew Zealand meet familiar opponents Pakistan at spin-friendly Premadasa

-

Features23 hours ago

Features23 hours agoVictor, the Friend of the Foreign Press

-

Latest News2 days ago

Latest News2 days agoTariffs ruling is major blow to Trump’s second-term agenda

-

Latest News2 days ago

Latest News2 days agoECB push back at Pakistan ‘shadow-ban’ reports ahead of Hundred auction