Features

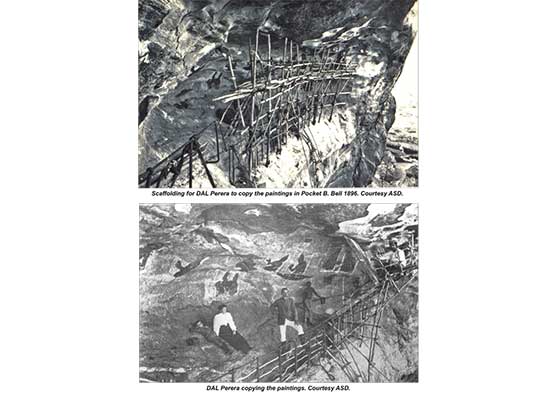

Dangerous and meticulous work copying Sigiriya frescoes in Bell era (1896)

(Excerpted from Sigiriya Paintings by Raja de Silva, retired Commissioner of Archaeology)

RE-DISCOVERY AND DOCUMENTATION (Early Visits)

The village of Sigiriya is mentioned in the 16th century book of Sinhala verse titled Mandarampura-puvata. From then on, the site seems to have disappeared from the public record until its rediscovery in the 19th century. Major Forbes of the 78th Highlanders and two companions rode from Polonnaruva through Minneriya and Peikkulam in search of Sigiriya, and reached the site early in the morning of a day in April 1831 (Forbes 1841).

They returned to the site two years later and Forbes explored further the cavernous walled gallery on the western side of the great rock, which led towards the summit. Forbes was surprised to observe a durable plaster on the brickwork of the wall, while above the gallery, especially in places protected from the elements, the plaster was seen to be painted over in bright  colours. However, he was disappointed and puzzled in not recognizing any representations of the lion, which, according to local lore, gave the name of Sigiri, i.e., Sinhagiri to the rock.

colours. However, he was disappointed and puzzled in not recognizing any representations of the lion, which, according to local lore, gave the name of Sigiri, i.e., Sinhagiri to the rock.

The lion that eluded Forbes was tracked down by the next visitor, who remained anonymous in recording his impressions in 1851 under the title “From the notebook of a traveller” in a magazine known as Young Ceylon. This early visitor described the gallery as a long cavernous fissure, the outer edges of which were deeply grooved and a brick wall raised there, nearly to the roof. The inner surface of the “cave” was described as “covered with a coating of white and polished chunam gleaming as if it were a month old”.

Some of the plaster from the ceiling and the rock side of the gallery had fallen off, but it was noted by the visitor that “there was a profusion of paintings, chiefly of lions, which is said to have given the name of Singaghery, Sihagiri or Seegiry to the ancient site”. No other visitor had reported on these lions.

Twenty four years later, Sigiriya and the paintings were brought to public notice by TW Rhys Davids (1875), formerly of the Ceylon Civil Service, in a lecture given before the Royal Asiatic Society, London. Rhys Davids described his observation, through a telescope, of the “hollow” halfway up the western side of the rock, with its surface covered with a fine hard “chunam” plaster on which were painted figures. He mentioned that the northern (i.e., further) area of the gallery was covered with ornamental paintings (again, to be lost not long after) and thought that a large number of these may have been erased with the passage of time. By the close of the century, when the Archaeological Survey Department (ASD) commenced work at Sigiriya, these paintings had all disappeared.

TH Blakesley (1976) Public Works Department, viewed the paintings from afar in 1875, and reported for the first time on their subject, which he recognized to be female figures “repeated again and again”, showing only the upper parts of their bodies, and richly ornamented with jewellery. The figures (he said) had a Mongolian cast of features. Blakesley also examined the plaster layer adhering to the accessible parts of the main rock, and remarked on the existence of paddy husks in the ground.

Reports of the existence of paintings at Sigiriya had attracted the attention of connoisseurs of art in Sri Lanka and in England, and Sir William Gregory, the former Governor, requested Alick Murray (1891), Provincial Engineer, to attempt to reach the paintings and make reproductions of them. This proposal was sanctioned by Sir Arthur Gordon, the Governor, who gave every encouragement to the project. Murray went to Sigiriya, fired with enthusiasm for this pioneering venture, but was disappointed to discover that the local villagers would have no part of his plans for disturbing the rock chamber which, they imagined, was inhabited by demons. The populace, however, was, persuaded to clear the jungle at the base of the rock in the required direction, while Murray awaited the arrival of Tamil labourers who were urgently requested from South India.

The Tamil stone-cutters (who had no fear of Sinhala demons) bored holes in the rock face, one above the other, into which were fixed with cement, iron jumpers. As they went higher up the rock towards the cavern containing the paintings, the man of the lightest weight had to be selected to bore the holes. After a while, even this labourer found it difficult to ascend higher. He supplicated that if he were allowed three days of fasting and prayer, he might succeed in finishing the task. Murray answered his prayer in the affirmative, thinking that it might lighten the man’s weight and thereby help him to reach the pocket containing the paintings. Once this goal was reached, it was found that the rock floor was at too steep an angle to permit one to stand or even sit on it. A strong trestle or framework of sticks was made and secured to iron stanchions let into the rock floor. A platform was made and placed on the framework to enable one to lie on his back and view the paintings.

On June 18, 1889, Murray made his historic climb into the fresco pocket, and he worked for a whole week lying on his back on makeshift scaffolding to make tracings of six paintings in coloured chalk on tissue paper. The work was done, climbing up and down each day, (as he said) “from sunrise to sunset”, the only inmates of the cavern being swallows who used to “peck at him resentfully”. When his work was reaching conclusion, a few of his friends including SM Burrows, Government Agent, Matale, hazarded the climb to the pocket to visit him, and it was suggested that a memento be left behind. A bottle was obtained and in it were deposited a newspaper of the day, a few coins, and a list of names of friends who had visited him at work. Murray’s party was astonished when a Buddhist monk and a Saivite priest sought permission to enter the chamber, and they were accommodated by Murray. They prayed for the preservation of the bottle, thereby adding solemnity to the occasion of its sealing into the floor with cement – a ceremony that was accompanied by Murray and Burrows singing “God Save the Queen”.

An unfortunate result of Murray’s excellent efforts at tracing the paintings under the windiest of conditions was that, on detaching the tracing papers that had been pasted with gum on the periphery of each figure, an egg-shell thin layer of painted plaster (i.e., the intonaco) also came away revealing a white framework of the layer of ground underneath. Another deplorable result was that a few Tamil labourers had scribbled their names on the painted plaster. The copies made by Murray were stated by Bell to have been exhibited above the staircase of the Colombo Museum.

Murray described the paintings as having been done on the roof and upper sections of the sides of the chamber; that they represent 15 female figures in all, but no doubt many more had existed originally, as traces of them were to be seen. The freshness of the colours (he observed) was wonderful, curiously, green predominating. Each figure was stated to have been life-size and many were naked to the waist, the rest of the form being hidden by representations of clouds. They were arranged either singly or in sets of two, each couple representing (he said) a mistress and a maid.

Access to Fresco Pockets

In 1896, Bell made regular access to the fresco pockets possible by the construction of a vertical ladder of jungle timber from the gallery to the cemented floor that was spread on the sloping -round of the rock cavern 40′ above. The shorter and narrower pocket A was made accessible from pocket B by a floor of iron planks set on iron rods as supports let into the surface of the rock horizontally and grouted in.

The early timber ladder was replaced by an iron wire vertical ladder with safety measures of hoops of cane and wire netting around it in 1896. A spiral staircase of iron steps was constructed in 1938. Another similar staircase was recently constructed by the Central Cultural Fund (CCF) cheek-by-jowl with the earlier construction, and is used as the method of access to the fresco pocket at a point to the south of the original doorway. Visitors now use the old stairway as the exit from the pocket.

Eighty five years ago entry to the fresco pockets was restricted to those who had obtained permits from the Archaeological Commissioner. (AC).

The public has the opportunity of taking their cameras into the fresco pockets, on permits issued by the ASD, and photographing the paintings. No persons are allowed to have their photographs taken in front of the paintings, and at least two guards are stationed inside the fresco pockets as a security measure. No electronic or other flash-lights are permitted in photographing the paintings.

Documentation and Copying of the Paintings

Bell decided to photograph the pockets from a distance at the same elevation, and record the disposition of the paintings within. For this purpose a four inch hawser was let down from the summit to the ground with an iron block tied to the end. Through the block a two inch rope was passed and an improvised chair firmly tied to it, whereon the photographer took his seat. The hawser was then hauled up from the summit, 150 feet up until the chair was level with the pocket and 50 feet clear of the cliff, but due to the force of the wind that caused it to sway in the air, the photographs taken were not clear.

It took DAL Perera, Chief Draughtsman and Bell’s “Native Assistant”, a week to do an oil painting to scale, while perilously suspended in mid-air like the man on the flying trapeze. The painting was later photographed and lithographed to make a plate. From the top of the iron ladder the rock curved inwards for four feet or so to an upward rising floor of pocket B where it was not possible to safely stand or even sit on the smooth surface. As a safeguard at the head of the ladder and along the entire edge of both pockets B and A to the north of it and the ledge between them, iron standards three foot three inches in height, with a single top rail, were driven into the rock Bell stated: “Without such a handrail, a slip on the smooth inclined floor of the pocket would have meant instant death on the rocks fifty yards below.”

In the last week of March 1896, Perera made copies of six paintings in pocket B while being dangerously seated on the sloping floor. In the following year with additional safeguards and working platforms, Perera continued copying the remaining paintings in the two pockets. Bell reported that 13 of the paintings in pocket B could be easily reached from the floor, being painted on the rock wall and the lower part of the oblique roof of the cave, but they were not at one level. It was these paintings that Perera copied in 1896 and 1897 while being uncomfortably perched on the sloping floor of the fresco pocket, which had in 1897 been cemented towards the outer edge.

The painting at the extreme south, i.e., No. 14 and the fragments No. 15, 16, 17, were out of reach and well up on the roof of the pocket. To get at these paintings, it was necessary to construct a “cantilever” of jungle timber, firmly lashed to a stout iron cramp let into the rock floor. To the end of this projection was tied a rough “cage” of sticks, from which uncomfortable and perilous perch Perera made copies of the last and highest figures in pocket B.

It was even more difficult and dangerous to fix a hurdle platform outside the narrow and slippery ledge separating pocket B from pocket A and onwards to the end of this pocket. It took 10 days to construct this stick-shelf (massa). In addition to P iron bars supporting the woodwork, the whole braced strongly to thick iron cramped into the rock, the platform had to be further held up by a central hawser and side ropes, hauled taut round trees on the summit 300 feet up. When finished this improvised platform stood out 15 feet from the cliff.

It took Perera 19 weeks to complete copying the 22 paintings – 5 in pocket A and 17 in pocket B.

The constructional details and measurements given above are intended to serve several purposes: to enable the reader to appreciate the labour and expertise in 1896 exercised by the authorities in setting up the elaborate apparatus for Perera to copy and photograph the paintings – all for the love of preserving our ancient artwork; to appreciate the great care taken by Perera under perilous conditions to make such excellent copies of 22 paintings, now exhibited in the Colombo Museum, which Bell extolled in superlative terms:

“It is hardly going too far to assert that the copies represent the original frescoes as they may still be seen at Sigiriya, with a faithfulness almost perfect. Not a line, not a flaw or abrasion, not a shade of colour, but has been reproduced with the minutest accuracy”. (Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society Ceylon Branch (1897).

The details and measurements are also intended to impress upon readers the magnitude of the feats of our craftsman in ancient times, who constructed broad, long scaffoldings rising to a height of around 400 feet using jungle timber and creepers; and to marvel that the artists painted their subject so well, during a very long period upon multi-layered plaster on the wind-blown exposed rock.

Features

How many more must die before Sri Lanka fixes its killer roads?

On the morning of May 11, 2025, the quiet hills of Ramboda were pierced by the wails of sirens and the cries of survivors. A Sri Lanka Transport Board (SLTB) bus, en route from Kataragama to Kurunegala via Nuwara Eliya, veered off the winding road and plunged down a deep precipice in the Garandiella area. At least 23 people lost their lives and more than 35 were injured—some critically.

The nation mourned. But this wasn’t merely an isolated accident. It was a brutal reminder of Sri Lanka’s long-standing and worsening road safety crisis––one where the poor pay the highest price, and systemic neglect continues to endanger thousands every day.

A national epidemic

According to the Central Bank of Sri Lanka’s 2023 Road Safety Report, buses and other passenger vehicles are involved in 60% of fatalities while motorcycles account for 35% of reported accidents. Though three-wheelers are often criticised in the media, they contribute to only 12% of all accidents. The focus, however, remains disproportionately on smaller vehicles—ignoring the real danger posed by larger, state-run and private buses.

The Ramboda incident reflects what transport experts and road safety advocates have long warned about: that Sri Lanka’s road accident problem is not primarily about vehicle type, but about systemic failure. And the victims—more often than not—are those who rely on public transport because they have no other choice.

One of the biggest contributors to the frequency and severity of road accidents is Sri Lanka’s crumbling infrastructure. A 2023 report by the Sri Lanka Road Development Authority (SLRDA) noted that nearly 40% of the country’s road network is in poor or very poor condition. In rural and hilly areas, this figure is likely higher. Potholes, broken shoulders, eroded markings, and inadequate lighting are all too common. In mountainous terrain like Ramboda, these conditions can be fatal.

Even worse, since 2015, road development has effectively stagnated. Although the Mahinda Rajapaksa administration was often criticised for its ambitious infrastructure drive, it left behind a network of wide, well-lit highways and urban improvements. The subsequent administrations not only failed to continue this momentum, but actively reversed course in some instances—most notably, with the cancellation of the Light Rail Transit (LRT) project in Colombo, which had been poised to modernise urban mobility and reduce congestion.

Instead of scaling up, Sri Lanka scaled down. Maintenance budgets were slashed, long-term projects shelved, and development planning took a back seat to short-term political calculations. Roads deteriorated, traffic congestion worsened, and safety standards eroded.

Dangerous drivers

Infrastructure is only part of the story. Human behaviour plays a significant role too—and Sri Lanka’s roads often mirror the lawlessness that prevails off them.

A 2022 survey by the Sri Lanka Road Safety Council revealed alarming patterns in driver behaviour: 45% of accidents involved drivers under the influence of alcohol or drugs, and 40% were attributed to speeding. These figures reflect not just recklessness, but a dangerous culture of impunity.

The legal blood alcohol limit for drivers in Sri Lanka is 0.08%, but enforcement remains lax, particularly in rural areas and during off-peak hours. There is no consistent system of random breath testing, and police checkpoints are often limited to high-profile holidays or urban areas.

The same lack of enforcement applies to speeding, tailgating, overtaking on blind corners, and ignoring traffic signals. While the law technically provides for penalties, in practice, enforcement is selective at best. Even SLTB bus drivers—tasked with transporting hundreds daily—are known for aggressive and erratic driving. The Ramboda bus is reported to have been speeding on a dangerously narrow bend, a pattern that has become disturbingly common.

Public buses, both state-run and private, are some of the most dangerous vehicles on the road today—not just due to their size, but because of operational cultures that prioritise speed over safety. Competition for passengers, poor driver training, minimal vehicle maintenance, and weak regulatory oversight have created a deadly combination.

Do they not deserve better?

Most people who travel in SLTB buses are from lower-income backgrounds. They rely on public transportation not by choice, but by necessity. A factory worker in Nuwara Eliya, a schoolteacher in Bandarawela, or a daily wage earner commuting between towns—all are bound to a public transport system that is increasingly unreliable and unsafe.

Sri Lanka’s social contract has failed its most vulnerable. The poor are expected to brave substandard buses on crumbling roads, driven by underpaid and undertrained drivers, often in hazardous weather and terrain. In many rural areas, buses are lifelines. When one crashes, it is not merely a tragedy—it’s a profound injustice.

Had the LRT system gone forward, had road maintenance been prioritised, had reckless drivers been reined in through strict enforcement, how many lives could have been saved?

Experts agree that the solution lies in a combination of infrastructure investment, driver education, and law enforcement reform. The Sri Lanka Road Safety Council has repeatedly called for mandatory road safety training, particularly for commercial drivers. Such training should cover not just traffic laws, but also defensive driving, fatigue management, and the dangers of DUI.

Enforcement, too, needs a dramatic overhaul. License suspensions, large fines, and jail time for repeat offenders must become the norm—not the exception. A centralised traffic violation database could prevent habitual offenders from slipping through the cracks.

And critically, investment in infrastructure must resume—not in flashy mega-projects for political gain, but in safe, functional, and equitable roads and transit systems. The re-introduction of the LRT or similar mass transit projects should be seriously reconsidered, especially in urban centers where congestion is growing and road space is limited.

The misunderstood three-wheeler

On the other hand, while three-wheelers are frequently vilified in public discourse and media narratives for reckless driving, the data tells a different story. According to the Central Bank’s 2023 Road Safety Report, they account for just 12% of all road accidents—a fraction compared to the 60% involving buses and other passenger vehicles, and the 35% attributed to motorcycles. Yet, disproportionate attention continues to be directed at three-wheelers, conveniently shifting focus away from the far greater risks posed by large, state-run and private buses.

What often goes unacknowledged is the essential role three-wheelers play in Sri Lanka’s transport ecosystem, particularly in remote and rural areas where reliable public transport is virtually nonexistent. For residents of small towns and isolated villages in the hill country, three-wheelers are not a luxury—they are a necessity. Affordable, nimble, and capable of navigating narrow, winding roads where buses cannot operate, these vehicles have become the primary mode of short-distance travel for countless Sri Lankans.

Even more importantly, in the aftermath of road accidents—especially in remote regions like Ramboda—it is often the three-wheeler drivers who are the first to respond. When tragedy strikes, they ferry the injured to hospitals, assist with rescue efforts, and offer immediate aid long before official emergency services arrive. This community-centered, grassroots role is rarely acknowledged in national conversations about road safety, yet it remains a vital, life-saving contribution.

Rather than treating three-wheelers as a problem to be blamed, the government should recognise their indispensable value and work towards integrating them more effectively and safely into the national transport framework. Regularising the sector through measures such as mandatory driver training programmes, periodic vehicle safety checks, and the enforcement of standardised operating licenses could improve safety without displacing an essential service. Additionally, designating official three-wheeler stands, particularly in high-risk or high-traffic areas, and incentivising drivers who maintain clean safety records would help create a safer, more accountable environment for both passengers and pedestrians.

Moving beyond the blame game

It is time for us to move beyond the tired narrative that blames specific vehicles—motorcycles, three-wheelers, or buses—for the carnage on Sri Lanka’s roads. The problem is not the mode of transport. It is the system that surrounds it.

When buses are poorly maintained, roads are not repaired, drivers are not trained, and laws are not enforced, tragedy becomes inevitable. Blaming a single vehicle type does nothing to address these root causes.

The real question is: Do we have the political will to fix this? Or will Sri Lanka continue to count the dead—accident after accident—while doing little more than issuing condolences?

The Ramboda accident was not the first. It won’t be the last. But it should be the turning point.Let this be the moment we stop pointing fingers—and start fixing the road.

(The writer is an Attorney-at-Law with over a decade of experience specializing in civil law, a former Board Member of the Office of Missing Persons, and a former Legal Director of the Central Cultural Fund. He holds an LLM in International Business Law and resides in Battaramulla, where he experiences the daily challenges of commuting to Hulftsdorp, providing him with a unique perspective on Sri Lanka’s road safety issues.)

By Sampath Perera

Features

J’accuse – Need for streamlined investigation of corruption in former President’s office

Though the government is moving more slowly on corruption than I would have liked, it is moving, which is more than can be said for its predecessors. I remember how sad I was when Yahapalanaya did very little, except for political advantage, about the corruption it had highlighted in the election campaign in which I had so foolishly joined; but the reason became clear with the bond scam, when the Ranil Wickremesinghe administration rose to heights of corruption that surpassed, in convoluted ingenuity, anything the Mahinda Rajapaksa government could have achieved. Thus far the present government is clean, and that will make its task much easier.

I hope then that the slow but steady progress of this government in investigation will bear fruit. But at the same time, I think it would also be good if it looked at instances when corruption was avoided. The horrors of the visa scam, in which the Controller General of Immigration seems to have connived with his political masters, suggest how important it is to also praise those civil servants who resist pressures.

With regard to the visa scam, I had thought Tiran Alles largely responsible, but perhaps I have done the man an injustice – if that were conceivable – and the fountainhead of the matter was the President. I now think this the more likely, having heard about a Civil Servant who did stand up against the political pressures brought upon him. If this government were to look into the matter, and recognise his integrity and courage, perhaps that would prompt the former Controller General of Immigration and Emigration too to come clean and turn Crown Witness, having accepted a compounded penalty for anything he might have done wrong.

It can be difficult to resist pressure. That must be understood though it is no reason to excuse such conduct. But it is therefore more essential to praise the virtuous, such as the former Secretary to the Ministry of Health, Dr Palitha Mahipala. I had heard of him earlier, and I am sorry he was removed, though I have also heard good things about his successor, so there is no reason to bring him back. But perhaps he could be entrusted with greater responsibilities, and awarded some sort of honour in encouragement of those with courage.

One of the notable things Dr Mahipala did was to resist pressure brought upon him to award a contract to Francis Maude, a British crony of the President. This was to design a supply chain management for pharmaceuticals. A system for this was already being designed by the Asian Development Bank, but when told about this the authorities had nevertheless insisted.

The then Secretary to the Prime Minister cannot absolve himself of the responsibility for having asked the Ministry of Health to prepare a stunningly expensive MoU that was quite unnecessary.

But his claim was that he had been introduced to the Britisher by a top aide of the President. This rings true for it was the President who first wished Maude upon the country. It was after all Ranil Wickremesinghe who, a year after he became President, announced that, to boost state revenue, Maude had been invited ‘to visit Sri Lanka and share his insights on sectoral reform’.

When he became a Minister under David Cameron, Maude’s responsibilities included ‘public service efficiency and transparency’. There seems to have been nothing about revenue generation, though the President’s statement claimed that ‘Sri Lanka must explore new avenues for increasing income tax revenues…He expressed concern over not only the neglect of public revenue but also the unrestricted spending of public funds on non-beneficial activities’.

He ‘called for an extensive media campaign to educate the public’ but this did not happen, doubtless because transparency went by the board, in his antics, including the demand, whoever prompted it, that Maude be to do something already done. Surely, this comes under the heading of unrestricted spending of public funds on non-beneficial activities, and it is difficult to believe that top government officials connived at promoting this while Ranil would have expressed concern had he known what they were up to.

Nothing further is recorded of Ranil’s original trumpeting of Maude’s virtues, and far from being there to provide advice on the basis of his experience in government, he seems to have been trawling for business for the firm he had set up on leaving politics, for it was with that private agency that the MoU was urged.

Thankfully, Dr Mahipala resisted pressure, and that plot came to nothing. But it should not be forgotten, and the government would do well to question those responsible for what happened, after speaking to Dr Mahipala and looking at the file.

Indeed, given the amount of corruption that can be traced to the President’s Office, it would make sense for the government to institute a Commission of Inquiry to look into what happened in that period of intensive corruption. It should be subject to judicial appeal, but I have no doubt that incisive questioning of those who ran that place would lead to enough information to institute prosecutions, and financial recompense for the abuses that occurred.

by Prof. Rajiva Wijesinha

Features

Trump’s Press Secretary; no attention to the health crisis

In her Cry on 25 April, Cassandra wrote this in her section on Trump’s moves to Make America Great Again – MAGA. “The latest was heard on BBC news on Wednesday 16. A fluff of a blonde White House press secretary by name of Karoline Leavitt announces that President Trump expects Harvard University to apologise to him for the continuing tolerance of anti-Semitism by the university. And that little blonde fluff adds ‘And they should.’ Didn’t Cass guffaw, but bitterly. That’s Trump vs Harvard.”

In her Cry on 25 April, Cassandra wrote this in her section on Trump’s moves to Make America Great Again – MAGA. “The latest was heard on BBC news on Wednesday 16. A fluff of a blonde White House press secretary by name of Karoline Leavitt announces that President Trump expects Harvard University to apologise to him for the continuing tolerance of anti-Semitism by the university. And that little blonde fluff adds ‘And they should.’ Didn’t Cass guffaw, but bitterly. That’s Trump vs Harvard.”

Karoline Leavitt

This young blonde has been making waves ever since, so much so that night shows in the US have spoken of her, and not well. Jimmy Kimmel arranged a dialogue between Karoline and Mark Carney, PM of Canada, when he recently visited the US. She insulted him by saying he did not know what democracy was and that Canada would benefit by becoming the 51st of the US. Carney vowed Canada was not for sale and never would be. The interview which was described in a video which I watched got hotter, Carney became cooler and Karoline rattled until she shot up and left the room. The usually noisy crowd that collects to listen to Kimmel roared – disdain.

Cass had to ferret more about her, so she went to the Internet. Born in 1997, Karoline Leavitt studied politics and communication at Saint Anselm College, which she entered on a games scholarship. She interned in the White House as an apprentice press secretary and was named a press secretary in Trump‘s first term. After Trump’s loss in 2020, she became a communications director for New York. She was the Republican candidate in the US House of Reps election for New Hampshire in 2022 but lost. She was much in Trump’s campaign against Biden’s winning and then served as a spokeswoman for MAGA Inc. In November 2024, Trump named her his White House Press Secretary, the youngest to hold this post in US history. All this seems to have gone to her blonde head!

Mosquitoes making life hell in Colombo

These pests are breeding like mad in and around Colombo and other parts of the country too. We can be tolerant of nature and its creatures, but the mosquito now is deadly. She passes on the dreaded diseases of chikungunya and dengue; the former debilitating for months after the grueling ache in bones is abated as the infection recedes. Dengue can be fatal if one’s platelet count goes below the red line.

The crux of the near pandemic of these two diseases is that infection and prevalence of the two could be greatly reduced by control of the carrier of the infection – The Mosquito. And on whom rests the responsibility of controlling the breeding of mosquitoes? On You and Me. But both of these entities are often careless, and totally non-caring about keeping their premises clean and of course eliminating all breeding spots for flying pests. Does the responsibility end there? Not upon your life! The buck moves on and lands on the public health inspectors, the garbage removers, the fumigators. Their boss who sees to them working properly is the Medical Officer of Health. And he is part of the Colombo Municipal Council that has the responsibility of looking to the health of people within the MC.

The spread of the two diseases mentioned is proof that the above persons and establishments are NOT doing the work they should be doing.

It is a proven fact that just before a change in personnel in the country, or a MC or a Pradeshiya Sabha, with a general election or local government election in the near future, most work stops in government offices or in local government establishments as the case may be. Workers get the disease of ennui; do minimum work until new bosses take over.

This definitely has happened in Colombo. Cass lives in Colombo 3. Quite frequent fumigation stopped some time ago. About two weeks ago she heard the process and smelled the fumes. Then nothing and mosquitoes breeding with the infrequent rain and no repellents or cleaning of premises. She phoned the MOH’s office on Thursday last week. Was promised fumigation. Nothing.

We are in a serious situation but no Municipal Council action. Politics is to blame here too. The SJB is trying to grab control of the Colombo MC and people are falling prey to the two diseases. All politicians shout it’s all for the people they enter politics, etc. The NPP has definitely shown concern for the public and have at least to a large extent eliminated corruption in public life. They have a woman candidate for Mayor who sure seems to be able to do a very good job. Her concern seems to be the people. But no. A power struggle goes on and its root cause: selfishness and non-caring of the good of the people. And for more than a week, the personnel from the MOH are looking on as more people suffer due to dirty surroundings.

Garbage is collected from her area on Tuesdays and Saturdays with paper, etc., on Thursdays. Tuesday 13 was a holiday but garbage was put out for collection. Not done. At noon, she phoned a supervisor of the cleaning company concerned only to ask whether the workers had a day off. Garbage was removed almost immediately. That is concern, efficiency and serving the public.

As Cass said, Colombo is in near crisis with two mosquito borne diseases mowing down people drastically. And nothing is being done by the officers who are given the responsibility of seeing to the cleanliness of the city and its suburbs.

-

Features6 days ago

Features6 days agoSAITM Graduates Overcome Adversity, Excel Despite Challenges

-

Opinion6 days ago

Opinion6 days agoDrs. Navaratnam’s consultation fee three rupees NOT Rs. 300

-

News6 days ago

News6 days agoDestined to be pope:Brother says Leo XIV always wanted to be a priest

-

Sports6 days ago

Sports6 days agoASBC Asian U22 and Youth Boxing Championships from Monday

-

Features5 days ago

Features5 days agoChampioning Geckos, Conservation, and Cross-Disciplinary Research in Sri Lanka

-

Business6 days ago

Business6 days agoDilmah – HSBC future writers festival attracts 150+ entries

-

Midweek Review3 days ago

Midweek Review3 days agoBronze statue for P’karan, NPP defeat in the North and 16th anniversary of triumph over terrorism

-

Business6 days ago

Business6 days agoBloom Hills Holdings wins Gold for Edexcel and Cambridge Education