Features

Crisis in Sri Lanka and the world

BOOK REVIEW

By W. D. Lakshman, Professor Emeritus,

University of Colombo

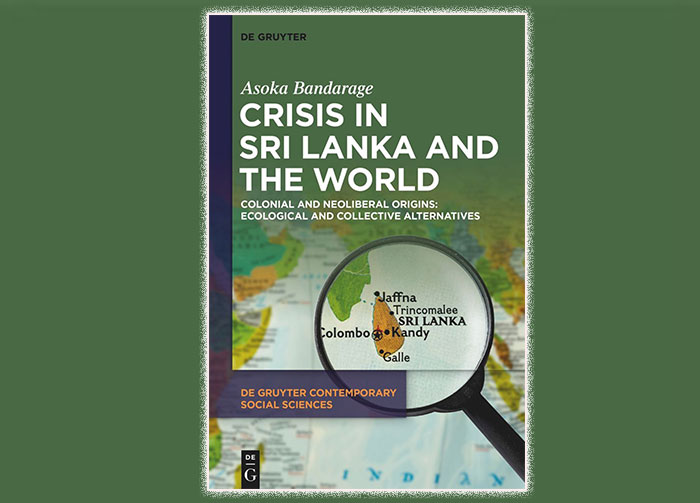

Asoka Bandarage, Crisis in Sri Lanka and the World: Colonial and Neoliberal Origins – Ecological and Collective Alternatives. De Gruyter Contemporary Social Sciences. Vol 30. Berlin and Boston: De Gruyter. 2023

Asoka Bandarage is known for her unconventional approach in several of her publications on development which extensively draw case study material from Sri Lanka. Her examination of the current crisis in Sri Lanka also employs an innovative analytical approach, setting it apart from most existing studies on the subject. Her willingness to depart from convention in this exercise is commendable. Notably, emerging economies like Sri Lanka are increasingly finding themselves in turmoil during this era of neoliberalism. Bandarage’s book, therefore, is a must-read for those seeking alternative methodological stances and more comprehensive perspectives on the analysis of socio-economic crises in emerging economies.

The crisis that emerged in Sri Lanka in 2022 has turned out to be of unprecedented severity, leading the country to declare insolvency and debt default for the first time in its history. At the time of the declaration of insolvency, the government reached out to the IMF for a package of measures to resolve the crisis. At the time of writing, the country has been on an IMF package for about eight months.

The IMF package has brought about some changes in the appearance of the crisis. However, many of the fundamental factors, viewed from a holistic angle, that led to the crisis appear to have been further aggravated by the solutions applied. The crisis continues to take its toll on the people in numerous ways.

Most available accounts, including that of the IMF, perceive this crisis as predominantly economic and financial in nature. However, what Sri Lanka is experiencing is a multi-faceted crisis characterised by diverse causes, consequences, and processes. It encompasses not only economic and financial dimensions but also social, nutritional, and health aspects, political and democratic failures, debt-related challenges, institutional and governance lacuna, bribery and corruption allegations, and ecological concerns. Each of these aspects interacts with the others in complex ways.

The remedial measures taken by the government, according to the IMF-written policy package, addressing as they do only a restricted part of the problem, have now made the crisis a very real and pressing concern for the ordinary people in the country. Regrettably, many analysts, particularly economists and financial analysts, continue to emphasise the economic, financial, and debt-related aspects of the crisis, thus neglecting other important factors of grave relevance. Some analysts bring some history into consideration in explaining the crisis, but for many of them, the relevant history does not go beyond a few years in the immediate past.

Furthermore, many accounts tend to view the crisis as a fundamentally Sri Lankan phenomenon, bringing into analysis only some international influences like fluctuations in oil prices or critical commodity scarcities in the world market, failing to recognise the critical influence of holistically viewed global developments as having pushed the country into this predicament.

In this context, Asoka Bandarage’s Crisis in Sri Lanka and the World (hereafter referred to as Crisis) stands out as a refreshing and much-needed addition to the body of literature addressing the Sri Lankan crisis of the 2020s. She provides a holistic viewpoint, highlighting the multifaceted nature of the crisis and tracing its origins back to Sri Lanka’s historical evolution from colonial times. The Crisis is perhaps the only comprehensive publication written from such a holistic approach so far.

The book commences with a conceptual overview in Chapter 1, where Bandarage combines different themes that she develops in further detail in subsequent chapters. She places particular emphasis on the historical origins of the crisis. In Chapter 2, she delves into the development of the plantation economy in Sri Lanka during the colonial era. The subsequent three chapters cover the early post-Independence period (Chapter 3: 1948-77), the early phase of the post-liberalization period (Chapter 4: 1977-2009), and the period immediately preceding the crisis of the early 2020s (Chapter 5: 2009-19).

In this comprehensive historical analysis, Bandarage offers a bird’s-eye view of Sri Lanka’s key socio-political and economic trends over nearly two centuries and their evolving dynamics. She underscores the global influences, originating from diverse sources and with varying degrees of impact, on Sri Lanka’s domestic economy and its trajectory. Within this historical account, Chapters 4 and 5, which cover the closest influences on the early 2020s crisis, hold particular significance.

Chapter 5 delves into the evaluation of geopolitical rivalry, neocolonialism, and political destabilisation, exploring the range of international factors influencing the crisis that emerged in the early 2020s. Influences from Chinese, Indian, and U.S. expansionism into the Indian Ocean region, and interventions from international organisations like the UN Human Rights Council (UNHCR). Mainstream reviews of the 2020s crisis do rarely cover as extensive a terrain as this dealing with the international political economy of the Sri Lankan crisis.

Bandarage thus brings in a fresh and innovative perspective, shedding light on uncharted terrain of profound relevance to the subject under consideration. Noteworthy in this regard, is her scrutiny of the contemporary influences of the United States, through diplomatic efforts, to secure agreements signed with Sri Lanka in respect of the Millennium Challenge Corporation (MCC) Compact, the Acquisition and Cross Services Agreement (ACSA), and the Status of Forces Agreement (SOFA).

Chapter 6 encompasses various themes that both characteride and explain the crisis. A central factor is Sri Lanka’s excessive and unbridled debt, particularly its heavy borrowings through International Sovereign Bonds. Bandarage labels this as “debt colonialism” imposed on the country. She also draws attention to the extreme income inequality and widening disparities in the country resulting from decades of neoliberalism. The adverse impact of these factors has been exacerbated by the crippling effects of COVID-19 during 2020-21 and the political turmoil following the protest movement known as the “aragalaya” against the then incumbent regime.

The events set in motion by these protests, culminating in the country’s submission to an IMF programme, are well-documented. The rise, during this kerfuffle, of a political leader known for his extreme right-wing views, described by Bandarage as a “long-time US collaborator” (p. 82), to the all-powerful position of the country’s presidency enabled the seamless implementation of the IMF programme with minimal resistance from the Sri Lankan government.

Bandarage concludes Chapter 6 by illustrating how the cumulative events led to Sri Lanka’s collapse, not only economically but also politically, socially, culturally, and psychologically. She paints a grim picture, stating, “Forces of global financial and corporate power are not leaving any room for the survival of a local economy or a national government that can meet the needs of its people.

The multifaceted crisis is leading to the demise of Sri Lanka’s sovereignty, turning the country into a mere shell of a state, wide open for more external political, economic, and military exploitation” (p. 198). The situation, no doubt, appears dire, but it is worth also noting that Sri Lanka has a history of resilience in overcoming challenges and emerging from crises.

Completing her holistic analysis, Bandarage explores the ecological dimension of the crisis in her final chapter, which has been used to examine ecological and collective alternatives to neoliberal globalisation. This chapter hints at some underlying optimism she shares for Sri Lanka’s future. Bandarage seeks “collective and ecological alternatives to the globalised system underlying perennial socioeconomic, cultural, and political crises, war and refugee crises, leading us to an existential crisis” (p. 204).

In alignment with Karl Polanyi’s viewpoint, she argues (pp. 207-8) that allowing the market mechanism to solely determine the fate of human beings and their natural environment would result in the destruction of society. Bandarage draws inspiration from the Middle Path in Buddhist philosophy, proposing it as a non-violent alternative to extremism of all kinds (p. 211). She advocates policies guided by the Middle Path philosophy to achieve the desired ecological and collective alternatives to neoliberal globalisation.

Several essential themes developed in the Crisis pertaining to the economic, financial, and indebtedness aspects of the 2020s crisis in Sri Lanka merit attention. These themes resonate with my own thinking and published work and hold significance, as they are often disregarded by independent reviewers and government advisors, both domestic and international, including those from International Financial Institutions (IFIs).

One such theme investigates the influence of extreme socio-economic inequality on the 2020s crisis in Sri Lanka. Inequality has persisted in Sri Lanka since the establishment of mercantile capitalism, i.e., the early stages of the colonial plantation economy. After gaining independence from colonial rule, there were brief spells of dominance of social democratic policies that aimed to reduce inequality. The neoliberal regime introduced in 1977 has exacerbated income disparities offsetting the egalitarian trends of the preceding decade.

This trend towards increasing inequality is a common feature of financialised global capitalism, particularly under neoliberal conditions. The super-rich oligarchy in society, often evading foreign exchange regulations and income and other tax rules, acted with detrimental effects on the country’s foreign exchange receipts and tax revenues, contributing to the foreign exchange and fiscal crises of the 2020s.

The rich trading classes (including large industry owners dependent heavily on imported inputs) and those engaged in the underground economy tend to maintain very large funds offshore. The changes in exchange control laws introduced in 2017 have facilitated these practices. Bandarage describes this behaviour as “plunder” by the country’s super-rich through “intentional, dodgy invoicing and stashing the foreign exchange earnings offshore” (p. 13). She refers to a total of US$ 36.833 billion as funds so kept illegally overseas. More recently, a cabinet minister in the incumbent government mentioned an even larger sum, $53.5 billion, held illegally overseas by Sri Lankan oligarchs (see The Island, 24 August 2023).

Either figure can be compared with the officially reported total foreign debt of $49.7 billion at the end of 2022 (Central Bank Annual Report, 2022, pp. 185-6). Furthermore, a significant part of the fiscal deficit issue, lying behind the huge public debt crisis, can be attributed to the non-payment of substantial volumes of tax dues by the wealthiest individuals in society. Tax avoidance and evasion are widely discussed topics. Rich mercantile classes avoid paying not only income tax but also the more revenue-generating indirect taxes of VAT, Import Duty, and Excise taxes.

The next point worth highlighting here is Sri Lanka’s well-known social democratic stance in respect of social policy matters – a matter already referred to briefly. This has been the case even during the post-1977 neoliberal period in matters pertaining to parts of production, trade, and finance. In this respect, the following statement of a leading political analyst is worth citing: ” … (T)he abiding democratic ethos of Sri Lanka (…) has never succumbed to dictatorship of the right or left, despite several civil wars. … This resilient electoral democracy has demonstrated a proclivity for social welfarism. Savage capitalism has never been sustainable here, nor has a foreign policy alien to the values of nonalignment” (Dayan Jayatilleka in The Island, Oct. 26, 2023).

This social ethos came to be established in the Sri Lankan political economy from as early as the 1930s. In 1931, a semi-independent governance system was set up, with a legislature (State Council) elected by the people on universal adult franchise and a Board of Ministers, three-tenths of which comprised of elected State Council members. A strong and widespread left-wing political movement led by a group of charismatic leaders committed to Marxist thinking and practice, developed in the country from this period onwards.

The principal elements of the social democratic stance in social policy, which evolved from this period onwards, was maintained even during the post-1977 neoliberal period. Key aspects of this social democratic ethos include free education, free health services, and the use of consumer and producer subsidies to support the average consumers and small-scale farmers and producers. Although changes have been introduced over time, especially following IMF programmes, the social democratic ethos remains robust. This is a main reason why conventional economic solutions failed to eliminate the dual deficits and debt issues in Sri Lanka.

Out-of-the-box thinking is essential to devise mechanisms that the people can accept to address these economic challenges. The IMF Extended Fund Facility of March 2023 further illustrates the challenges of implementing a stabilization package defined and drafted without giving due care to socio-political peculiarities in Sri Lanka. Policy makers and their advisers are well advised to carefully read Bandarage’s Crisis in search perhaps of useful insights into how policy processes could be modified to achieve improved results.

Features

The US-China rivalry and challenges facing the South

The US-China rivalry could be said to make-up the ‘stuff and substance’ of world politics today but rarely does the international politics watcher and student of the global South in particular get the opportunity of having a balanced and comprehensive evaluation of this crucial relationship. But such a balanced assessment is vitally instrumental in making sense of current world power relations.

The US-China rivalry could be said to make-up the ‘stuff and substance’ of world politics today but rarely does the international politics watcher and student of the global South in particular get the opportunity of having a balanced and comprehensive evaluation of this crucial relationship. But such a balanced assessment is vitally instrumental in making sense of current world power relations.

Thanks to the Regional Centre for Strategic Studies (RCSS), Colombo the above window of opportunity was opened on December 8th for those sections of the public zealously pursuing an understanding of current issues in global politics. The knowledge came via a forum that was conducted at the RCSS titled, ‘The US-China Rivalry and Implications for the Indo-Pacific’, where Professor Neil DeVotta of the Wake Forest University of North Carolina in the US, featured as the speaker.

A widely representative audience was present at the forum, including senior public servants, the diplomatic corps, academics, heads of civil society organizations, senior armed forces personnel and the media. The event was ably managed by the Executive Director of the RCSS, retired ambassador Ravinatha Aryasinha. Following the main presentation a lively Q&A session followed, where many a point of interest was aired and discussed.

While there is no doubt that China is fast catching up with the US with regard to particularly military, economic, scientific and technological capability, Prof. DeVotta helped to balance this standard projection of ‘China’s steady rise’ by pointing to some vital facts about China, the omission of which would amount to the observer having a somewhat uninformed perception of global political realities.

The following are some of the facts about contemporary China that were highlighted by Prof. DeVotta:

* Money is steadily moving out of China and the latter’ s economy is slowing down. In fact the country is in a ‘ Middle Income Trap’. That is, it has reached middle income status but has failed to move to upper income status since then.

* People in marked numbers are moving out of China. It is perhaps little known that some Chinese are seeking to enter the US with a view to living there. The fact is that China’s population too is on the decline.

* Although the private sector is operative in China, there has been an increase in Parastatals; that is, commercial organizations run by the state are also very much in the fore. In fact private enterprises have begun to have ruling Communist Party cells in them.

* China is at its ‘peak power’ but this fact may compel it to act ‘aggressively’ in the international sphere. For instance, it may be compelled to invade Taiwan.

* A Hard Authoritarianism could be said to characterize central power in China today, whereas the expectation in some quarters is that it would shift to a Soft Authoritarian system, as is the case in Singapore.

* China’s influence in the West is greater than it has ever been.

The speaker was equally revelatory about the US today. Just a few of these observations are:

* The US is in a ‘Unipolar Moment’. That is, it is the world’s prime power. Such positions are usually not longstanding but in the case of the US this position has been enjoyed by it for quite a while.

* China is seen by the US as a ‘Revisionist Power’ as opposed to being a ‘Status Quo Power.’ That is China is for changing the world system slowly.

* The US in its latest national security strategy is paying little attention to Soft Power as opposed to Hard Power.

* In terms of this strategy the US would not allow any single country to dominate the Asia-Pacific region.

* The overall tone of this strategy is that the US should step back and allow regional powers to play a greater role in international politics.

* The strategy also holds that the US must improve economic ties with India, but there is very little mention of China in the plan.

Given these observations on the current international situation, a matter of the foremost importance for the economically weakest countries of the South is to figure out how best they could survive materially within it. Today there is no cohesive and vibrant collective organization that could work towards the best interests of the developing world and Dr. DeVotta was more or less correct when he said that the Non-alignment Movement (NAM) has declined.

However, this columnist is of the view that rather being a spent force, NAM was allowed to die out by the South. NAM as an idea could never become extinct as long as economic and material inequalities between North and South exist. Needless to say, this situation is remaining unchanged since the eighties when NAM allowed itself to be a non-entity so to speak in world affairs.

The majority of Southern countries did not do themselves any good by uncritically embracing the ‘market economy’ as a panacea for their ills. As has been proved, this growth paradigm only aggravated the South’s development ills, except for a few states within its fold.

Considering that the US would be preferring regional powers to play a more prominent role in the international economy and given the US’ preference to be a close ally of India, the weakest of the South need to look into the possibility of tying up closely with India and giving the latter a substantive role in advocating the South’s best interests in the councils of the world.

To enable this to happen the South needs to ‘get organized’ once again. The main differences between the past and the present with regard to Southern affairs is that in the past the South had outstanding leaders, such as Jawaharlal Nehru of India, who could doughtily stand up for it. As far as this columnist could ascertain, it is the lack of exceptional leaders that in the main led to the decline of NAM and other South-centred organizations.

Accordingly, an urgent task for the South is to enable the coming into being of exceptional leaders who could work untiringly towards the realization of its just needs, such as economic equity. Meanwhile, Southern countries would do well to, indeed, follow the principles of NAM and relate cordially with all the major powers so as to realizing their best interests.

Features

Sri Lanka and Global Climate Emergency: Lessons of Cyclone Ditwah

Tropical Cyclone Ditwah, which made landfall in Sri Lanka on 28 November 2025, is considered the country’s worst natural disaster since the deadly 2004 tsunami. It intensified the northeast monsoon, bringing torrential rainfall, massive flooding, and 215 severe landslides across seven districts. The cyclone left a trail of destruction, killing nearly 500 people, displacing over a million, destroying homes, roads, and railway lines, and disabling critical infrastructure including 4,000 transmission towers. Total economic losses are estimated at USD 6–7 billion—exceeding the country’s foreign reserves.

The Sri Lankan Armed Forces have led the relief efforts, aided by international partners including India and Pakistan. A Sri Lanka Air Force helicopter crashed in Wennappuwa, killing the pilot and injuring four others, while five Sri Lanka Navy personnel died in Chundikkulam in the north while widening waterways to mitigate flooding. The bravery and sacrifice of the Sri Lankan Armed Forces during this disaster—as in past disasters—continue to be held in high esteem by grateful Sri Lankans.

The Sri Lankan government, however, is facing intense criticism for its handling of Cyclone Ditwah, including failure to heed early warnings available since November 12, a slow and poorly coordinated response, and inadequate communication with the public. Systemic issues—underinvestment in disaster management, failure to activate protocols, bureaucratic neglect, and a lack of coordination among state institutions—are also blamed for avoidable deaths and destruction.

The causes of climate disasters such as Cyclone Ditwah go far beyond disaster preparedness. Faulty policymaking, mismanagement, and decades of unregulated economic development have eroded the island’s natural defenses. As climate scientist Dr. Thasun Amarasinghe notes:

“Sri Lankan wetlands—the nation’s most effective natural flood-control mechanism—have been bulldosed, filled, encroached upon, and sold. Many of these developments were approved despite warnings from environmental scientists, hydrologists, and even state institutions.”

Sri Lanka’s current vulnerabilities also stem from historical deforestation and plantation agriculture associated with colonial-era export development. Forest cover declined from 82% in 1881 to 70% in 1900, and to 54–50% by 1948, when British rule ended. It fell further to 44% in 1954 and to 16.5% by 2019.

Deforestation contributes an estimated 10–12% of global greenhouse gas emissions. Beyond removing a vital carbon sink, it damages water resources, increases runoff and erosion, and heightens flood and landslide risk. Soil-depleting monocrop agriculture further undermines traditional multi-crop systems that regenerate soil fertility, organic matter, and biodiversity.

In Sri Lanka’s Central Highlands, which were battered by Cyclone Ditwah, deforestation and unregulated construction had destabilised mountain slopes. Although high-risk zones prone to floods and landslides had long been identified, residents were not relocated, and construction and urbanisation continued unchecked.

Sri Lanka was the first country in Asia to adopt neoliberal economic policies. With the “Open Economy” reforms of 1977, a capitalist ideology equating human well-being with quantitative growth and material consumption became widespread. Development efforts were rushed, poorly supervised, and frequently approved without proper environmental assessment.

Privatisation and corporate deregulation weakened state oversight. The recent economic crisis and shrinking budgets further eroded environmental and social protections, including the maintenance of drainage networks, reservoirs, and early-warning systems. These forces have converged to make Sri Lanka a victim of a dual climate threat: gradual environmental collapse and sudden-onset disasters.

Sri Lanka: A Climate Victim

Sri Lanka’s carbon emissions remain relatively small but are rising. The impact of climate change on the island, however, is immense. Annual mean air temperature has increased significantly in recent decades (by 0.016 °C annually between 1961 and 1990). Sea-level rise has caused severe coastal erosion—0.30–0.35 meters per year—affecting nearly 55% of the shoreline. The 2004 tsunami demonstrated the extreme vulnerability of low-lying coastal plains to rising seas.

The Cyclone Ditwah catastrophe was neither wholly new nor surprising. In 2015, the Geneva-based Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre (IDMC) identified Sri Lanka as the South Asian country with the highest relative risk of disaster-related displacement: “For every million inhabitants, 15,000 are at risk of being displaced every year.”

IDMC also noted that in 2017 the country experienced seven disaster events—mainly floods and landslides—resulting in 135,000 new displacements and that Sri Lanka “is also at risk for slow-onset impacts such as soil degradation, saltwater intrusion, water scarcity, and crop failure”.

Sri Lanka ranked sixth among countries most affected by extreme weather events in 2018 (Germanwatch) and second in 2019 (Global Climate Risk Index). Given these warnings, Cyclone Ditwah should not have been a surprise. Scientists have repeatedly cautioned that warmer oceans fuel stronger cyclones and warmer air holds more moisture, leading to extreme rainfall. As the Ceylon Today editorial of December 1, 2025 also observed:

“…our monsoons are no longer predictable. Cyclones form faster, hit harder, and linger longer. Rainfall becomes erratic, intense, and destructive. This is not a coincidence; it is a pattern.”

Without urgent action, even more extreme weather events will threaten Sri Lanka’s habitability and physical survival.

A Global Crisis

Extreme weather events—droughts, wildfires, cyclones, and floods—are becoming the global norm. Up to 1.2 billion people could become “climate refugees” by 2050. Global warming is disrupting weather patterns, destabilising ecosystems, and posing severe risks to life on Earth. Indonesia and Thailand were struck by the rare and devastating Tropical Cyclone Senyar in late November 2025, occurring simultaneously with Cyclone Ditwah’s landfall in Sri Lanka.

More than 75% of global greenhouse gas emissions—and nearly 90% of carbon emissions—come from burning coal, oil, and gas, which supply about 80% of the world’s energy. Countries in the Global South, like Sri Lanka, which contribute least to greenhouse gas emissions, are among the most vulnerable to climate devastation. Yet wealthy nations and multilateral institutions, including the World Bank, continue to subsidise fossil fuel exploration and production. Global climate policymaking—including COP 30 in Belém, Brazil, in 2025—has been criticised as ineffectual and dominated by fossil fuel interests.

If the climate is not stabilised, long-term planetary forces beyond human control may be unleashed. Technology and markets are not inherently the problem; rather, the issue lies in the intentions guiding them. The techno-market worldview, which promotes the belief that well-being increases through limitless growth and consumption, has contributed to severe economic inequality and more frequent extreme weather events. The climate crisis, in turn, reflects a profound mismatch between the exponential expansion of a profit-driven global economy and the far slower evolution of human consciousness needed to uphold morality, compassion, generosity and wisdom.

Sri Lanka’s 2025–26 budget, adopted on November 14, 2025—just as Cyclone Ditwah loomed—promised subsidised land and electricity for companies establishing AI data centers in the country.

President Anura Kumara Dissanayake told Parliament: “Don’t come questioning us on why we are giving land this cheap; we have to make these sacrifices.”

Yet Sri Lanka is a highly water-stressed nation, and a growing body of international research shows that AI data centers consume massive amounts of water and electricity, contributing significantly to greenhouse gas emissions.

The failure of the narrow, competitive techno-market approach underscores the need for an ecological and collective framework capable of addressing the deeper roots of this existential crisis—both for Sri Lanka and the world.

A landslide in Sri Lanka (AFP picture)

Ecological and Human Protection

Ecological consciousness demands

recognition that humanity is part of the Earth, not separate from it. Policies to address climate change must be grounded in this understanding, rather than in worldviews that prize infinite growth and technological dominance. Nature has primacy over human-created systems: the natural world does not depend on humanity, while humanity cannot survive without soil, water, air, sunlight, and the Earth’s essential life-support systems.

Although a climate victim today, Sri Lanka is also home to an ancient ecological civilization dating back to the arrival of the Buddhist monk Mahinda Thera in the 3rd century BCE. Upon meeting King Devanampiyatissa, who was out hunting in Mihintale, Mahinda Thera delivered one of the earliest recorded teachings on ecological interdependence and the duty of rulers to protect nature:

“O great King, the birds of the air and the beasts of the forest have as much right to live and move about in any part of this land as thou. The land belongs to the people and all living beings; thou art only its guardian.”

A stone inscription at Mihintale records that the king forbade the killing of animals and the destruction of trees. The Mihintale Wildlife Sanctuary is believed to be the world’s first.

Sri Lanka’s ancient dry-zone irrigation system—maintained over more than a millennium—stands as a marvel of sustainable development. Its network of interconnected reservoirs, canals, and sluices captured monsoon waters, irrigated fields, controlled floods, and even served as a defensive barrier. Floods occurred, but historical records show no disasters comparable in scale, severity, or frequency to those of today. Ancient rulers, including the legendary reservoir-builder King Parākramabāhu, and generations of rice farmers managed their environment with remarkable discipline and ecological wisdom.

The primacy of nature became especially evident when widespread power outages and the collapse of communication networks during Cyclone Ditwah forced people to rely on one another for survival. The disaster ignited spontaneous acts of compassion and solidarity across all communities—men and women, rich and poor, Buddhists, Christians, Muslims, and Hindus. Local and international efforts mobilized to rescue, shelter, feed, and emotionally support those affected. These actions demonstrated a profound human instinct for care and cooperation, often filling vacuums left by formal emergency systems.

Yet spontaneous solidarity alone is insufficient. Sri Lanka urgently needs policies on sustainable development, environmental protection, and climate resilience. These include strict, science-based regulation of construction; protection of forests and wetlands; proper maintenance of reservoirs; and climate-resilient infrastructure. Schools should teach environmental literacy that builds unity and solidarity, rather than controversial and divisive curriculum changes like the planned removal of history and introduction of contested modules on gender and sexuality.

If the IMF and international creditors—especially BlackRock, Sri Lanka’s largest sovereign bondholder, valued at USD 13 trillion—are genuinely concerned about the country’s suffering, could they not cancel at least some of Sri Lanka’s sovereign debt and support its rebuilding efforts? Addressing the climate emergency and the broader existential crisis facing Sri Lanka and the world ultimately requires an evolution in human consciousness guided by morality, compassion, generosity and wisdom. (Courtesy: IPS NEWS)

Dr Asoka Bandarage is the author of Colonialism in Sri Lanka: The Political Economy of the Kandyan Highlands, 1833-1886 (Mouton) Women, Population and Global Crisis: A Politico-Economic Analysis (Zed Books), The Separatist Conflict in Sri Lanka: Terrorism, Ethnicity, Political Economy, ( Routledge), Sustainability and Well-Being: The Middle Path to Environment, Society and the Economy (Palgrave MacMillan) Crisis in Sri Lanka and the World: Colonial and Neoliberal Origins, Ecological and Collective Alternatives (De Gruyter) and numerous other publications. She serves on the Advisory Boards of the Interfaith Moral Action on Climate and Critical Asian Studies.

Features

Cliff and Hank recreate golden era of ‘The Young Ones’

Cliff Richard and Hank Marvin’s reunion concert at the Riverside Theatre in Perth, Australia, on 01 November, 2025, was a night to remember.

Cliff Richard and Hank Marvin’s reunion concert at the Riverside Theatre in Perth, Australia, on 01 November, 2025, was a night to remember.

The duo, who first performed together in the 1950s as part of The Shadows, brought the house down with their classic hits and effortless chemistry.

The concert, part of Cliff’s ‘Can’t Stop Me Now’ tour, featured iconic songs like ‘Summer Holiday’, ‘The Young Ones’, ‘Bachelor Boy’, ‘Living Doll’ and a powerful rendition of ‘Mistletoe and Wine.’

Cliff, 85, and Hank, with his signature red Fender Stratocaster, proved that their music and friendship are timeless.

According to reports, the moment the lights dimmed and the first chords of ‘Move It’ rang out, the crowd knew they were in for something extraordinary.

Backed by a full band, and surrounded by dazzling visuals, Cliff strode onto the stage in immaculate form – energetic and confident – and when Hank Marvin joined him mid-set, guitar in hand, the audience erupted in applause that shook the hall.

Together they launched into ‘The Young Ones’, their timeless 1961 hit which brought the crowd to its feet, with many in attendance moved to tears.

The audience was treated to a journey through time, with vintage film clips and state-of-the-art visuals adding to the nostalgic atmosphere.

Highlights of the evening included Cliff’s powerful vocals, Hank’s distinctive guitar riffs, and their playful banter on stage.

Cliff posing for The Island photographer … February,

2007

Cliff paused between songs to reflect on their shared journey saying:

“It’s been a lifetime of songs, memories, and friendship. Hank and I started this adventure when we were just boys — and look at us now, still up here making noise!”

As the final chords of ‘Congratulations’ filled the theatre, the crowd rose for a thunderous standing ovation that lasted several minutes.

Cliff waved, Hank gave a humble bow, and, together, they left the stage, arm-in-arm, to the refrain of “We’re the young ones — and we always will be.”

Reviews of the show were glowing, with fans and critics alike praising the duo’s energy, camaraderie, and enduring talent.

Overall, the Cliff Richard and Hank Marvin reunion concert was a truly special experience, celebrating the music and friendship that has captivated audiences for decades.

When Cliff Richard visited Sri Lanka, in February, 2007, I was invited to meet him, in his suite, at a hotel, in Colombo, and I presented him with my music page, which carried his story, and he was impressed.

In return, he personally autographed a souvenir for me … that was Cliff Richard, a truly wonderful human being.

-

News3 days ago

News3 days agoOver 35,000 drug offenders nabbed in 36 days

-

Business5 days ago

Business5 days agoLOLC Finance Factoring powers business growth

-

Features1 day ago

Features1 day agoFinally, Mahinda Yapa sets the record straight

-

News2 days ago

News2 days agoCyclone Ditwah leaves Sri Lanka’s biodiversity in ruins: Top scientist warns of unseen ecological disaster

-

News5 days ago

News5 days agoCPC delegation meets JVP for talks on disaster response

-

News5 days ago

News5 days agoA 6th Year Accolade: The Eternal Opulence of My Fair Lady

-

News3 days ago

News3 days agoRising water level in Malwathu Oya triggers alert in Thanthirimale

-

Features4 days ago

Features4 days agoThe Catastrophic Impact of Tropical Cyclone Ditwah on Sri Lanka: