Features

Counselling the Human Rights Council: A perspective by the Pathfinder Foundation

As the 46th session of the UN Human Rights Council (HRC) looms large in about a month’s time, the debate on its controversial Resolution 30/1 of 2015, which the ‘Yahapalana Government’ co-owned in an unprecedented and unwise move, has resumed with renewed vigour.

This is because the Res. 30/1 adopted in 2015 ‘runs out’ this year and the HRC, egged on by the so called ‘core group’ of Western countries – the pilots of 30/1- will feel obliged to take stock of the situation and see where they want to go from here.

That Resolution 30/1 is in a class by itself in both form and content would be obvious to any reasonably literate person, including its most ardent supporters.

Even the harshest critic of Res. 30/1 and its spin-offs must concede that it was a bold move about a seemingly intractable situation. However, it is also probably the first instance in the history of the HRC, that a supposedly sovereign and independent country co-authored a UN Resolution containing an array of highly intrusive, unconstitutional and unimplementable demands directed at itself.

It probably scores another first in that the self-authored Resolution touches upon a range of governance matters, which are generally considered the exclusive preserve of the domestic jurisdiction of the authoring Member state itself viz, Sri Lanka. There does not appear to be any precedent of such self-inflicted State action in UN records.

In advance of the 34th Session, way back in 2017, the Pathfinder Foundation urged the then government to undertake renegotiation of the HRC resolution, based on ground realities in Sri Lanka, rather than seeking a postponement of consideration of the situation in the country.

It may be unique as well, for the reason that in no other democratic country a HRC resolution had been so instrumental in delivering so massive an electoral defeat to the incumbent government that cosponsored the resolution.

The HRC and the fellow internationals that generally get busy exploring how to ‘helpfully intervene’ in Sri Lanka about this time every year, must understand the reality that it is a function of the free franchise in one of the two oldest democracies in South Asia.

There was a groundswell of opinion in this country against the resolution, which was initiated by a group of countries, who had only a limited understanding of Sri Lanka. It was seen as a blatant interference in a small sovereign nation by virtually forcing it to ‘outsource’ the oversight of and judgment on many governance matters to a secretariat in distant Geneva.

Even those in Sri Lanka and abroad, who believed that successive regimes in Sri Lanka have accumulated quite an inventory of post conflict challenges to address, felt that Resolution 30/1 was a ‘bad template’ for HRC to promote international cooperation on human rights. This was because some provisions of that resolution had failed elsewhere (the so-called Hybrid Courts in Cambodia); some were unconstitutional/unimplementable (foreign judges): a watching brief on governance matters was conferred on a Secretariat based in Geneva and a dedicated UN office in Colombo was proposed for the oversight of these activities. That all these were at variance with the UN Charter, was of no concern to the ill-advised Core- Group on Sri Lanka.

This kind of ham-handed innovations to existing international law and institutions that can even contribute to regime change is not a good model to propound, if the HRC is serious about encouraging and persuading countries, particularly those of the developing world, to work in cooperation with the Council.

Instead, the Council would have been well-advised to develop and propose robust and independent domestic accountability processes, supported where necessary, by international cooperation in technical assistance, advisory services, best practices etc.

Pathfinder believes such an approach, which is advisory, rather than retributive in nature will:

work within normal national and international legal norms;

serve as a model for other countries needing such services, to cooperate with the UN; and

not function as a disincentive for countries that are willing to voluntarily cooperate.

So, it was no surprise that the Sri Lankan Foreign Minister was obliged, consequent to the electoral mandate the newly elected government had received, to announce the government’s withdrawal of co-sponsorship of Res. 30/1 at the 45th session of the HRC.

So, what next?

Has Sri Lanka’s inventory of accountability and reconciliation issues become non-existent? Obviously not.

Has HRC enhanced its credibility for promoting templates to encourage countries with difficult and complex issues in this field to cooperate with the Council? Obviously not.

Will countries with a good track record of voluntary cooperation, continue to do so in the face of such new, intrusive and unconstitutional modalities? Obviously not.

The current context and a way forward

On the High Commissioner for Human Rights (HCHR) side, the Secretariat has felt obliged to issue yet another heavily front–loaded report this year with even more intrusive recommendations. Some of them sound bizarre to say the least, as they refer to now familiar western parlance of ‘targeted measures, assets freeze’ and so on. Even if one sets aside the rather offensive and unrealistic nature of such utterances against a sovereign country, which had consistently and continuously cooperated with the HRC, it must be clear to anyone that these ‘innovations’ are counterproductive as far as addressing the real issues of cooperation were concerned, for no country will accept such invasive measures.

Such actions will face hugely divided votes in the UN General Assembly and definite vetoes in the Security Council. Apart from the feel-good factor for the enthusiastic sponsors, they have little or no practical value for addressing the real issue at the ground level.

On the GOSL side, even as it pulled out of the co sponsorship of 30/1 owing to electoral compulsions, Colombo has made it clear (at the HRC itself) that the withdrawal of co-sponsorship does not mean a withdrawal of Sri Lanka’s responsibilities concerning reconciliation and accountability. President Rajapaksa himself, while emphasizing that the country will not rule out the possibility of walking out of any entity that will not respect the accepted principles of sovereignty and independence of countries, did affirm that his government is fully committed to international cooperation including with the UN on SDGs, which of course include human rights, peace and justice related matters.

It is also a fact that Sri Lanka has continued to work effectively with various Special Procedure Mandates or Rapporteurs of HRC. If these Rapporteurs were unable to visit the country in the recent past, that was not due to change of policy by the government. As we all know, 2020 was an extraordinary year with COVID 19 taking its toll worldwide.

There are openings one can make use of and elements one can build upon, if we are serious about encouraging international cooperation among sovereign countries rather than unacceptable unilateral coercion.

If this is not done, and common ground is not created, Pathfinder is of the view that there are two options available to the sponsors of the initiative and to Sri Lanka at the forthcoming HRC session:

(a) Acknowledge the need to continue to address and resolve issues of accountability and reconciliation in Sri Lanka by preserving and building upon progress made so far (e. g. Office of Missing Persons, Compensation, Rehabilitation, Socio-economic upliftment etc.) and in that regard, offer and receive international cooperation where necessary, including with the UN, for technical assistance and advisory services.

OR

(b) If, however, the sponsors continue to insist on undeliverable and unconstitutional solutions (eg. as in Res 30/1 and 40/1), Sri Lanka to completely withdraw from the HRC process and work towards a domestic consensus on the matter.

During the nearly 30 years of an injurious conflict, Sri Lanka remained a good example of cooperation with external entities including the UN on human rights and humanitarian matters, despite many complex countervailing factors (security, political, diplomatic and economic). The UN Secretary General’s Special Representative Olara Otunnu, who visited Sri Lanka in 1998 said so in reference to Govt’s continued supply of food, medicine, health, education and other essential services to the LTTE ‘controlled’ areas. It would therefore be a pity, if such willing Member States are dissuaded from continuing such policy by HRC pitching their prescription bars at an undeliverable and un-constitutional height.

In such an eventuality, Sri Lanka and like-minded Member States will be obliged to press such resolutions to a highly divisive vote in the Council. Even if the resolution is adopted by a slim majority, Sri Lanka is most likely to ignore it and pitch her bilateral ‘economic tents’ with countries that vote in its favour. Such a resolution will not therefore help the cause of accountability and reconciliation one bit and will simply add to the considerable number other resolutions already ignored by countries like China, Cuba, India, Israel, the U.S., and so on. Even if it is elevated to the UNGA, it will suffer a highly divided vote and a definite veto in UN Security Council.

Pathfinder believes that only a negotiated consensual way forward, rather than unilateral actions either by Sri Lanka or the initiators of any resolution, will advance the cause of human rights in Sri Lanka at this difficult juncture. Adding to the paperwork at the HRC with no prospect of implementation at the ground level will not enhance the utility or credibility of HRC’s tool kit for international cooperation in human Rights. Of course, such a resolution will help increase the ‘feel good factor’ on the part of the Core-Group on Sri Lanka.

In conclusion, the Pathfinder Foundation would like to ask as to whether the Core-Group on Sri Lanka expects to get its job done by resorting to confrontation and browbeating of a member state, instead of cooperating and engage in consultation? If the answer is yes, then those countries representing the South in the HRC will think deeply before they cast their vote in support of another meaningless and intrusive resolution.

This is the PATHFINDER VIEW POINT of Counselling the Human Rights Council issued by the Pathfinder Foundation. Readers’ comments via email to pm@pathfinderfoundation.org are welcome.

Features

Removing obstacles to development

Six months into the term of office of the new government, the main positive achievements continue to remain economic and political stability and the reduction of waste and corruption. The absence of these in the past contributed to a significant degree to the lack of development of the country. The fact that the government is making a serious bid to ensure them is the best prognosis for a better future for the country. There is still a distance to go. The promised improvements that would directly benefit those who are at the bottom of the economic pyramid, and the quarter of the population who live below the poverty line, have yet to materialise. Prices of essential goods have not come down and some have seen sharp increases such as rice and coconuts. There are no mega projects in the pipeline that would give people the hope that rapid development is around the corner.

There were times in the past when governments succeeded in giving the people big hopes for the future as soon as they came to power. Perhaps the biggest hope came with the government’s move towards the liberalisation of the economy that took place after the election of 1977. President J R Jayewardene and his team succeeded in raising generous international assistance, most of it coming in the form of grants, that helped to accelerate the envisaged 30 year Mahaweli Development project to just six years. In 1992 President Ranasinghe Premadasa thought on a macro scale when his government established 200 garment factories throughout the country to develop the rural economy and to help alleviate poverty. These large scale projects brought immediate hope to the lives of people.

More recently the Hambantota Port project, Mattala Airport and the Colombo Port City project promised mega development that excited the popular imagination at the time they commenced, though neither of them has lived up to their envisaged potential. These projects were driven by political interests and commission agents rather than economic viability leading to debt burden and underutilisation. The NPP government would need to be cautious about bringing in similar mega projects that could offer the people the hope of rapid economic growth. During his visits to India and China, President Anura Kumara Dissanayake signed a large number of agreements with the governments of those countries but the results remain unclear. The USD 1 billion Adani project to generate wind power with Indian collaboration appears to be stalled. The USD 3.7 billion Chinese proposal to build an oil refinery also appears to be stalled.

RENEWED GROWTH

The absence of high profile investments or projects to generate income and thereby take the country to a higher level of development is a lacuna in the development plans of the government. It has opened the door to invidious comparisons to be drawn between the new government’s ability to effect change and develop the economy in relation to those in the opposition political parties who have traditionally been in the seats of power. However, recently published statistics of the economic growth during the past year indicates that the economy is doing better than anticipated under the NPP government. Sri Lanka’s economy grew by 5 percent in the year 2024, reversing two years of contraction with the growth rate for the year of 2023 being estimated at negative 2.3 percent. What was particularly creditable was the growth rate for the fourth quarter of 2024 (after the new government took over) being 5.4 percent. The growth figures for the present quarter are also likely to see a continuation of the present trend.

Sri Lanka’s failure in the past has been to sustain its economic growth rates. Even though the country started with high growth rates under different governments, it soon ran into problems of waste and corruption that eroded those gains. During the initial period of President J R Jayawardene’s government in the late 1970s, the economy registered near 8 percent growth with the support of its mega projects, but this could not be sustained. Violent conflict, waste and corruption came to the centre stage which led to the economy getting undermined. With more and more money being spent on the security forces to battle those who had become insurgents against the state, and with waste and corruption skyrocketing there was not much left over for economic development.

The government’s commitment to cut down on waste and corruption so that resources can be saved and added to enable economic growth can be seen in the strict discipline it has been following where expenditures on its members are concerned. The government has restricted the cabinet to 25 ministers, when in the past the figure was often double. The government has also made provision to reduce the perks of office, including medical insurance to parliamentarians. The value of this latter measure is that the parliamentarians will now have an incentive to upgrade the health system that serves the general public, instead of running it down as previous governments did. With their reduced levels of insurance coverage they will need to utilise the public health facilities rather than go to the private ones.

COMMITTED GOVERNMENT

The most positive feature of the present time is that the government is making a serious effort to root out corruption. This is to be seen in the invigoration of previously dormant institutions of accountability, such as the Bribery and Corruption Commission, and the willingness of the Attorney General’s Department to pursue those who were previously regarded as being beyond the reach of the law due to their connections to those in the seats of power. The fact that the Inspector General of Police, who heads the police force, is behind bars on a judicial order is an indication that the rule of law is beginning to be taken seriously. By cost cutting, eliminating corruption and abiding by the rule of law the government is removing the obstacles to development. In the past, the mega development projects failed to deliver their full benefits because they got lost in corrupt and wasteful practices including violent conflict.

There is a need, however, for new and innovative development projects that require knowledge and expertise that is not necessarily within the government. So far it appears that the government is restricting its selection of key decision makers to those it knows, has worked with and trusts due to long association. Two of the committees that the government has recently appointed, the Clean Lanka task force and the Tourism advisory committee are composed of nearly all men from the majority community. If Sri Lanka is to leverage its full potential, the government must embrace a more inclusive approach that incorporates women and diverse perspectives from across the country’s multiethnic and multireligious population, including representation from the north and east. For development that includes all, and is accepted by all, it needs to tap into the larger resources that lie outside itself.

By ensuring that women and ethnic minorities have representation in decision making bodies of the government, the government can harness a broader range of skills, experiences, and perspectives, ultimately leading to more effective and sustainable development policies. Sustainable development is not merely about economic growth; it is about inclusivity and partnership. A government that prioritises diversity in its leadership will be better equipped to address the challenges that can arise unexpectedly. By widening its advisory base and integrating a broader array of voices, the government can create policies that are not only effective but also equitable. Through inclusive governance, responsible economic management, and innovative development strategies the government will surely lead the country towards a future that benefits all its people.

by Jehan Perera

Features

Revisiting Non-Alignment and Multi-Alignment in Sri Lanka’s foreign policy

Former Minister Ali Sabry’s recent op-ed, “Why Sri Lanka must continue to pursue a non-aligned, yet multi-aligned foreign policy,” published in the Daily FT on 3 March, offers a timely reflection on Sri Lanka’s foreign policy trajectory in an increasingly multipolar world. Sabry’s articulation of a “non-aligned yet multi-aligned” approach is commendable for its attempt to reconcile Sri Lanka’s historical commitment to non-alignment with the realities of contemporary geopolitics. However, his framework raises critical questions about the principles of non-alignment, the nuances of multi-alignment, and Sri Lanka’s role in a world shaped by great power competition. This response seeks to engage with Sabry’s arguments, critique certain assumptions, and propose a more robust vision for Sri Lanka’s foreign policy.

Former Minister Ali Sabry’s recent op-ed, “Why Sri Lanka must continue to pursue a non-aligned, yet multi-aligned foreign policy,” published in the Daily FT on 3 March, offers a timely reflection on Sri Lanka’s foreign policy trajectory in an increasingly multipolar world. Sabry’s articulation of a “non-aligned yet multi-aligned” approach is commendable for its attempt to reconcile Sri Lanka’s historical commitment to non-alignment with the realities of contemporary geopolitics. However, his framework raises critical questions about the principles of non-alignment, the nuances of multi-alignment, and Sri Lanka’s role in a world shaped by great power competition. This response seeks to engage with Sabry’s arguments, critique certain assumptions, and propose a more robust vision for Sri Lanka’s foreign policy.

Sabry outlines five key pillars of a non-aligned yet multi-aligned foreign policy:

- No military alignments, no foreign bases: Sri Lanka should avoid entangling itself in military alliances or hosting foreign military bases.

- Economic engagement with all, dependency on none

: Sri Lanka should diversify its economic partnerships to avoid over-reliance on any single country.

* Diplomatic balancing

: Sri Lanka should engage with multiple powers, leveraging relationships with China, India, the US, Europe, Japan, and ASEAN for specific benefits.

- Leveraging multilateralism

: Sri Lanka should participate actively in regional and global organisations, such as UN, NAM, SAARC, and BIMSTEC.

- Resisting coercion and protecting sovereignty

: Sri Lanka must resist external pressures and assert its sovereign right to pursue an independent foreign policy.

While pillars 1, 2, and 5 align with the traditional principles of non-alignment, pillars 3 and 4 warrant closer scrutiny. Sabry’s emphasis on “diplomatic balancing” and “leveraging multilateralism” raises questions about the consistency of his approach with the spirit of non-alignment and whether it adequately addresses the challenges of a multipolar world.

Dangers of over-compartmentalisation

Sabry’s suggestion that Sri Lanka should engage with China for infrastructure, India for regional security and trade, the US and Europe for technology and education, and Japan and ASEAN for economic opportunities reflects a pragmatic approach to foreign policy. However, this compartmentalisation of partnerships risks reducing Sri Lanka’s foreign policy to a transactional exercise, undermining the principles of non-alignment.

Sabry’s framework, curiously, excludes China from areas like technology, education, and regional security, despite China’s growing capabilities in these domains. For instance, China is a global leader in renewable energy, artificial intelligence, and 5G technology, making it a natural partner for Sri Lanka’s technological advancement. Similarly, China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) offers significant opportunities for economic development and regional connectivity. By limiting China’s role to infrastructure, Sabry’s approach risks underutilising a key strategic partner.

Moreover, Sabry’s emphasis on India for regional security overlooks the broader geopolitical context. While India is undoubtedly a critical partner for Sri Lanka, regional security cannot be addressed in isolation from China’s role in South Asia. The Chinese autonomous region of Xizang (Tibet) is indeed part of South Asia, and China’s presence in the region is a reality that Sri Lanka must navigate. A truly non-aligned foreign policy would seek to balance relationships with both India and China, rather than assigning fixed roles to each.

Sabry’s compartmentalisation of partnerships risks creating silos in Sri Lanka’s foreign policy, limiting its flexibility and strategic depth. For instance, by relying solely on the US and Europe for technology and education, Sri Lanka may miss out on opportunities for South-South cooperation with members of BRICS.

Similarly, by excluding China from regional security discussions, Sri Lanka may inadvertently align itself with India’s strategic interests, undermining its commitment to non-alignment.

Limited multilateralism?

Sabry’s call for Sri Lanka to remain active in organisations like the UN, NAM, SAARC, and BIMSTEC is laudable. However, his omission of the BRI, BRICS, and the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation (SCO) is striking. These platforms represent emerging alternatives to the Western-dominated global order and offer Sri Lanka opportunities to diversify its partnerships and enhance its strategic autonomy.

The BRI is one of the most ambitious infrastructure and economic development projects in history, involving over 140 countries. For Sri Lanka, the BRI offers opportunities for infrastructure development, trade connectivity, and economic growth. By participating in the BRI, Sri Lanka can induce Chinese investment to address its infrastructure deficit and integrate into global supply chains. Excluding the BRI from Sri Lanka’s foreign policy framework would be a missed opportunity.

BRICS and the SCO represent platforms for South-South cooperation and multipolarity. BRICS, in particular, has emerged as a counterweight to such Western-dominated institutions as the IMF and World Bank, advocating for a more equitable global economic order. The SCO, on the other hand, focuses on regional security and counterterrorism, offering Sri Lanka a platform to address its security concerns in collaboration with major powers like China, Russia, and India. By engaging with these organisations, Sri Lanka can strengthen its commitment to multipolarity and enhance its strategic autonomy.

Non-alignment is not neutrality

Sabry’s assertion that Sri Lanka must avoid taking sides in major power conflicts reflects a misunderstanding of non-alignment. Non-alignment is not about neutrality; it is about taking a principled stand on issues of global importance. During the Cold War, non-aligned countries, like Sri Lanka, opposed colonialism, apartheid, and imperialism, even as they avoided alignment with either the US or the Soviet Union.

Sri Lanka’s foreign policy, under leaders like S.W.R.D. Bandaranaike and Sirimavo Bandaranaike, was characterised by a commitment to anti-colonialism and anti-imperialism, opposing racial segregation and discrimination in both its Apartheid and Zionist forms. Sri Lanka, the first Asian country to recognise revolutionary Cuba, recognised the Palestine Liberation Organisation (PLO) and the Provisional Revolutionary Government of South Vietnam, supported liberation struggles in Africa, and opposed the US military base in Diego Garcia. These actions were not neutral; they were rooted in a principled commitment to justice and equality.

Today, Sri Lanka faces new challenges, including great power competition, economic coercion, and climate change. A truly non-aligned foreign policy would require Sri Lanka to take a stand on issues like the genocide in Gaza, the colonisation of the West Bank, the continued denial of the right to return of ethnically-cleansed Palestinians and Chagossians, the militarisation of the Indo-Pacific, the use of economic sanctions as a tool of coercion, and the need for climate justice. By avoiding these issues, Sri Lanka risks becoming the imperialist powers’ cringing, whingeing client state.

The path forward

Sabry’s use of the term “multi-alignment” reflects a growing trend in Indian foreign policy, particularly under the BJP Government. However, multi-alignment is not the same as multipolarity. Multi-alignment implies a transactional approach to foreign policy, where a country seeks to extract maximum benefits from multiple partners without a coherent strategic vision. Multipolarity, on the other hand, envisions a world order where power is distributed among multiple centres, reducing the dominance of any single power.

Sri Lanka should advocate for a multipolar world order that reflects the diversity of the global South. This would involve strengthening platforms like BRICS, the SCO, and the NAM, while also engaging with Western institutions like the UN and the WTO. By promoting multipolarity, Sri Lanka can contribute to a more equitable and just global order, in line with the principles of non-alignment.

Ali Sabry’s call for a non-aligned, yet multi-aligned foreign policy falls short of articulating a coherent vision for Sri Lanka’s role in a multipolar world. To truly uphold the principles of non-alignment, Sri Lanka must:

* Reject compartmentalisation

: Engage with all partners across all domains, including technology, education, and regional security.

* Embrace emerging platforms

: Participate in the BRI, BRICS, and SCO to diversify partnerships and enhance strategic autonomy.

* Take principled stands

: Advocate for justice, equality, and multipolarity in global affairs.

* Promote South-South cooperation

: Strengthen ties with other Global South countries to address shared challenges, like climate change and economic inequality.

By adopting this approach, Sri Lanka can reclaim its historical legacy as a leader of the non-aligned movement and chart a course toward a sovereign, secure, and successful future.

(Vinod Moonesinghe read mechanical engineering at the University of Westminster, and worked in Sri Lanka in the tea machinery and motor spares industries, as well as the railways. He later turned to journalism and writing history. He served as chair of the Board of Governors of the Ceylon German Technical Training Institute. He is a convenor of the Asia Progress Forum, which can be contacted at asiaprogressforum@gmail.com.)

by Vinod Moonesinghe

Features

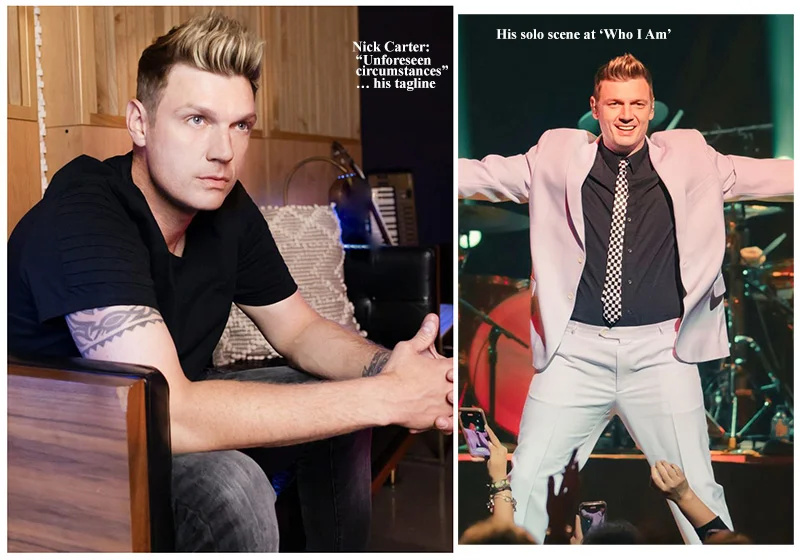

Nick Carter …‘Who I Am’ too strenuous?

Cancellation of shows has turned out to be a regular happening where former Backstreet Boys Nick Carter is concerned. In the past, it has happened several times.

Cancellation of shows has turned out to be a regular happening where former Backstreet Boys Nick Carter is concerned. In the past, it has happened several times.

If Nick Carter is not 100 percent fit, he should not undertake these strenuous world tours, ultimately disappointing his fans.

It’s not a healthy scene to be cancelling shows on a regular basis.

In May 2024, a few days before his scheduled visit to the Philippines, Carter cancelled his two shows due to “unforeseen circumstances.”

The promoter concerned announced the development and apologised to fans who bought tickets to Carter’s shows in Cebu, on May 23, and in Manila, on May 24.

The dates were supposed to be part of the Asian leg of his ‘Who I Am’ 2024 tour.

Carter previously cancelled a series of solo concerts in Asia, including Jakarta, Mumbai, Singapore, and Taipei. And this is what the organisers had to say:

“Due to unexpected matters related to Nick Carter’s schedule, we regret to announce that Nick’s show in Asia, including Jakarta on May 26 (2024), has been cancelled.

His ‘Who I Am’ Japan tour 2024 was also cancelled, with the following announcement:

Explaining, on video, about the

cancelled ‘Who I Am’ shows

“We regret to announce that the NICK CARTER Japan Tour, planned for June 4th at Toyosu PIT (Tokyo) and June 6th at Namba Hatch (Osaka), will no longer be proceeding due to ‘unforeseen circumstances.’ We apologise for any disappointment.

Believe me, I had a strange feeling that his Colombo show would not materialise and I did mention, in a subtle way, in my article about Nick Carter’s Colombo concert, in ‘StarTrack’ of 14th January, 2025 … my only worry (at that point in time) is the HMPV virus which is reported to be spreading in China and has cropped up in Malaysia, and India, as well.

Although no HMPV virus has cropped up, Carter has cancelled his scheduled performance in Sri Lanka, and in a number of other countries, as well, to return home, quoting, once again, “unforeseen circumstances.”

“Unforeseen circumstances” seems to be his tagline!

There is talk that low ticket sales is the reason for some of his concerts to be cancelled.

Yes, elaborate arrangements were put in place for Nick Carter’s trip to Sri Lanka – Meet & Greet, Q&A, selfies, etc., but all at a price!

Wonder if there will be the same excitement and enthusiasm if Nick Carter decides to come up with new dates for what has been cancelled?

-

Business5 days ago

Business5 days agoCargoserv Shipping partners Prima Ceylon & onboards Nestlé Lanka for landmark rail logistics initiative

-

News3 days ago

News3 days agoSeniors welcome three percent increase in deposit rates

-

Features3 days ago

Features3 days agoThe US, Israel, Palestine, and Mahmoud Khalil

-

Business5 days ago

Business5 days agoSri Lankans Vote Dialog as the Telecommunication Brand and Service Brand of the Year

-

News3 days ago

News3 days agoScholarships for children of estate workers now open

-

News4 days ago

News4 days agoDefence Ministry of Japan Delegation visits Pathfinder Foundation

-

Features5 days ago

Features5 days agoThe Vaping Veil: Unmasking the dangers of E-Cigarettes

-

News5 days ago

News5 days ago‘Deshabandu is on SLC payroll’; Hesha tables documents