Features

Corporations, Boards and Foundations

By Leelananda De Silva

One of the occupational hazards of the Planning Ministry was that one is obliged to serve on boards of corporations as a member. By statute and by practice, the Planning Ministry was represented on many governing boards. I represented the Ministry on several of them, and serving on these boards was interesting and instructive. Whether I contributed to the work of these organizations is something I cannot say.

I had a busy schedule of my own, and the time I could spare to the work of these boards was not much. My policy was to attend board meetings whenever I could and keep myself informed of the board agendas whenever I could not attend, so that I could inform the chairmen of my views on any relevant item. I made it a policy to be engaged at the board level only on key policy and other substantive issues. I did not want to be involved in the administrative items which were a major part of board agendas. I left it to the chairmen to handle that kind of subject.

In this way, I could focus on the issues that interested the Planning Ministry. Throughout my service on these boards, I had a cordial relationship with all the chairmen. I had a free hand in my decisions at these board meetings and it was rarely that I kept H.A.de.S (Gunasekera, Permanent Secretary to the Ministry of Planning and Economic Affairs) or the Prime Minister informed. The fact that I was representing the Planning Ministry and the minister who was Prime Minister gave me considerable influence whenever I was intervening on an issue of interest to me. Whenever I was out of the country, the chairmen always kept me informed and adjusted agendas on any important item which they thought the Planning Ministry would be interested in. It is in these ways that I could be an effective representative on these boards.

I was a member of the Tea Board from its inception in 1974 until 1977. The Tea Board brought together the separate entities of the Tea Controller, Tea Research Institute and the Tea Promotion Board, and it functioned under the Ministry of Plantation Industries. There were three chairmen in my time. The two most notable of them were Doric de Souza and Bertie Warusawitharane, and I was to travel with them to Rome for FAO meetings.

One board member was G.V.S. de Silva, who had been a brilliant economist, university lecturer and the man behind the Paddy Lands Act, advising Philip Gunawardana in the 1950s. Another was Hector Divitotawela, a well known planter, who happened to be the Prime Minister’s sister’s husband. The chief executive was Mahinda Dunuwille, highly competent and very knowledgeable on all aspect of the tea industry. So was T. Sambasivam who was the deputy.

I do not want to describe in any detail the work of the Tea Board and I shall confine myself to one or two snapshots of my experience there. I have already dealt with elsewhere the paper I presented to the Tea Board on the London Tea auctions. Another paper I presented to the Tea Board was on the subject of a tea museum. The sterling and rupee company estates were being taken over and there were many artefacts on these estates, which would be valuable in relating the story of tea in Sri Lanka. With the transfer of ownership, there was a danger that they would be lost, and I know that such losses took place.

My proposal was to establish a tea museum somewhere in the upcountry, preferably on a tea estate which would relate the history of Ceylon tea over a period of 75 years. While the proposal was adopted, nothing came of it, as the climate of opinion at the time was to forget about colonial experiences. A tea museum was later established and that was after many of the artifacts that would have been of interest had been lost.

There is another little nugget of a story. I was visiting London on official business and happened to visit the London Tea Centre which is run by the Tea Board. Attached to the Centre was a Sri Lankan restaurant which was very popular. The main purpose of the Tea Centre was to promote Sri Lankan tea with appropriate displays of various types of tea, and the restaurant was an ancillary business. What I found when I went there one day for lunch was that the Centre was closed during the lunch hours of 11.30 a.m. to 2.00 p.m. and the reason for this was that some of the staff were engaged at the restaurant and the others were out for lunch.

This was a ridiculous practice, as those were the hours when there were visitors and opportunities for tea sales. I explained this to the Tea Centre people and when I came back to Colombo, I told the Tea Board about it. This practice was changed, and the Tea Centre remained open during the lunch intervals subsequently. What I was amazed was that the Tea Centre people had so misplaced their priorities that running a restaurant became more important than running the Tea Centre.

I was a member of most of the boards dealing with ports and shipping between 1972 and 1977. I was a member of the board of the Port Cargo Corporation, Ceylon Shipping Corporation, Colombo Dockyards Limited and the Central Freight Bureau. All these boards had one thing in common. The chairman was PB Karandawela (Karande). He was one of the most efficient public servants I have ever met. He was master of the organizations he ran, apart from being Secretary of the Ministry of Shipping and Tourism.

During these years, he crafted a comprehensive policy for the development of the shipping industry in Sri Lanka and built up the Ceylon Shipping Corporation as a profitable enterprise. He stood up to the strong vested interests, specially the British shippers who dominated the carrying of cargo in and out of Sri Lanka. There was a gentleman by the name of P.J Hudson, representing the Conference Lines of the time, coming annually to Sri Lanka always with bad news for Sri Lanka’s freight rates. The Conference Lines had an iron grip on Sri Lanka’s trade. Karande broke that monopoly.

He developed a farseeing training policy for Shipping Corporation staff, equipping them with all the range of skills that a shipping firm requires. He left a highly skilled and very competent staff. I have not seen that kind of commitment to training in any other Sri Lankan institution. Karande died young after joining the UN in Geneva as Registrar of Shipping and serving for 10 years. We saw a lot of him and his wife, Geetha during his time in Geneva. He left for Tasmania as his wife was teaching maritime law there. A few months before his death in Tasmania, he visited us in England, and came for our daughter’s wedding in 1992. He was a great friend and it is sad that his life ended so prematurely. His services to the Sri Lanka shipping industry has never been adequately recognized.

There was a dedicated team of officers at the Shipping Corporation. I came to know many of them. David Soysa, was an old hand from the Commerce Department, and now a close colleague of Karande in both the Ministry and the Shipping Corporation. There was Ranjith de Silva, general manager of the Corporation and Mahinda Katugaha, the legal officer, who later joined the World Food Programme in Rome. These were all highly competent officers. The Minister whom I met many times was P.B.G Kalugalle, and his private secretary Wilbert Perera, a charming Mr. Fixit if ever there was one.

A major concern of the Minister was to get employment for as many constituents from Kegalle (he was MP there) in the various corporations under his ministry. He left Karande to get on with his job. I must record that although I was on their boards, the Freight Bureau and Colombo Dockyards were of marginal interest to me. There is one person I cannot forget who was involved in many of these things and that was Harold Speldewinde, who was a real authority on every aspect of ports and shipping. He had long experience with the private sector and Karande brought him in to the ministry. I enjoyed talking with him and if I have any knowledge of shipping and ports, I owe a lot to Harold.

There was also Tommy Ellawala, whom I got to know well who was an advisor to Karande on various matters although he was in the private sector. Michael Mack also served in a similar capacity. At that time, there was a very friendly atmosphere among Karande’s extended shipping circles. On the board of the corporation I was privileged to work with Chandra Cooray of the Treasury, Dr. S.T.G. Fernando from the Ministry of Trade, and Charlie Amarasekara.

Before I leave shipping, there is one little contribution of my own. I prepared a brief paper and got the approval of the board for Shipping Corporation vessels to carry cargo destined for charitable organizations in Sri Lanka free of charge. This could be done without any costs to the Corporation as there was much free space in most vessels.

I must mention one foreign trip which I made with Karande and David Soysa. We went to New Delhi in 1974 to negotiate an agreement with the Indian Shipping Corporation, whose chairman was C.P. Srivastava, who was later to become the head of the UN International Maritime Organization in London. It was a friendly discussion over three or four days and we enjoyed our stay at the Ashok Hotel in New Delhi. I did not have the time to travel on Shipping Corporation business on any other occasion.

I was fascinated by the ports and shipping industry. There were many colourful characters I came across. At the Port Cargo Corporation, the Chairman was Hubert A. de Silva and later Babu Dolapihille. Hubert left early to join the private sector, and I worked with Babu who knew everything about the port. The Colombo port ran smoothly during those days, and that period saw the start of containerization. On the Board of the Port Cargo Corporation were D.B.I.P.S Siriwardhana, then Principal Collector of Customs, whom I got to know well over a period of five years.

Then there was K. Sittampalam, Director of Finance at the Treasury and very knowledgeable about the intricacies of government finance. Among the officials, the one I came to know well was Dayasiri Muthumala, the chief accountant, with an extensive knowledge of port operations. He was later to have a long career in London with the International Maritime Organization.

The Shipping Corporation nominated me to be on the board of Mackinnon Mackenzie & Co. Ltd, when it bought 40 percent of that company. That was a mandatory purchase by legislation. I looked upon this assignment as a fascinating experiment in public-private partnerships. The management was with the private sector, as they controlled 60 percent of the company. I hardly ever missed attending their board meetings, and they were good enough to schedule these meetings to suit me. They were anxious to have a good working relationship with the Shipping Corporation and the government.

My policy once again was to allow them to manage the company and for me to be kept informed on key issues. I had a very happy time with Mackinnons. When I first joined the board, the chairman was Adrian Wijemanne whom I had known from my days in the Land Commissioner’s department, where he was deputy. He had left the public service and joined the private sector. The next chairman was F.G.N (Ricky) Mendis, who owned Mackinnons. Ricky and his wife Charmaine were to be good friends of ours from that time (much later, Charmaine and Ricky visited us in Geneva and we drove to Leichtenstein for a holiday). Ricky sold his shareholding to John Keells a little while later. With the sale to John Keells, D.P.D.M de Silva, a charming gentleman became chairman and we worked very well together. Mark Bostock, a legendary British businessman who had a major say at John Keells also came on to the board.

The board during this time was a very enterprising one and the experience in working with the private sector was illuminating. Two of the chief executives of Mackinnon’s, D.S.P.S. de Silva and Cyril Lawrence were outstanding business executives. Much later on a history of John Keells has been written and I am pleased to see an extensive reference to me, and to my contribution in making this private public partnership work. I learned a lot about business and the private sector from my experience at Mackinnon’s.

I was a director of the National Savings Bank, which came under the Ministry of Finance. M.Sanmuganathan (Sam), its chairman was a friend of mine and be persuaded me to come on to the Board to fill the Planning Ministry slot. There was little room for any initiatives in running this bank, as its investments were mainly in treasury assets. It was also funding the government’s financial demands. I remember one incident which is instructive.

The Minister, Dr N.M Perera had told the chairman to recruit a clerk, who was a niece of the jailor who had assisted Dr N.M to escape from jail during the war years. I told Sam that this is not right and if the minister wished to have her recruited, he should give a direction to that effect, which he was entitled to do under the legislation establishing the bank. With difficulty I persuaded him to go to the Minister with me and others and to explain our difficulty. Initially the Minister was angry but he calmed down and said he would issue a directive.

I mention this incident to illustrate the independence we as public officials had to conduct official business fairly, without being frightened of politicians. Dr. N.M never held that against me and he was always friendly and had a cordial relationship even after he left office. We had a common interest in cricket and also the London School of Economics (LSE). A few years after, he came to Geneva and visited us. He was on his way to London and he told me that he would like to go to the LSE where he was a well-known figure in the late 1920s and got his DSc. He studied under Harold Laski. By the time he came to Geneva, he had no contacts with LSE. So I contacted Peter Dawson at the LSE and he met NM and showed him round. Peter told me that N.M’s thesis on the Weimar constitution was one of the well thumbed documents in the library.

In the 1970s, we still had the University of Ceylon. The Permanent Secretary of Planning was on the board of the University board of governors. H.A.de.S nominated me to be the representative on his behalf. I attended board meetings from time to time. Once there was a most distressing episode. The vice chancellor had presented a paper to the senate to appoint a particular gentleman to be the professor of international relations. This was a newly created chair. Regrettably, the vice chancellor after a hurried advertisement and superficial interviews had recommended the appointment of a gentleman who was a lecturer in political theory and without any background in international relations, to be the new professor.

There was a highly suitable candidate in Shelton Kodikara, who was in the department of political science and who has written on international relations. He was on leave from the university and was Sri Lanka’s deputy high commissioner in Madras. He got to know about the chair after the applications had closed. When this came up to the Senate, I made a strong protest to the vice chancellor and suggested that he should advertise the post again so that Shelton Kodikara could apply. There was much recrimination at this senate meeting. The vice chancellor advertised the post again and appointed Shelton Kodikara as the first professor of international relations. Regrettably, the vice chancellor and I ceased to be friends.

Let me now go to a different type of board. I was appointed to be a member of the Board of the United States Educational Foundation (USEF), now the Fulbright Commission. It managed the Fulbright programme in this country. It was not a large technical assistance programme, but it did very useful work. The board consisted of three members of the US embassy which included its cultural affairs officer (during my time it was Dick Ross), and three members from Sri Lanka nominated by the Secretary of the Planning Ministry. The US Ambassador was the nominal chairman of the Board, and at that time, it was Chris Van Hollen who was to become a good friend of ours.

H.A.de.S appointed me to be on the board. During my time, there were many members on the Sri Lanka side. Premadasa Udagama, the Secretary of Education was there during my five years on the Board. The others who served for shorter spells were W.J.F. Labrooy, Professor of History at Peradeniya university and who had been my lecturer in history, Dr. Daphne Attygalle, Professor of Pathology and Prof. B. Hewavitharana, Professor of Economics. Aelian Fernando, a former vice principal of Wesley was the chief executive.

During this assignment of mine, I received much assistance from Miss. Diana Captain, who was in the cultural section of the embassy. She had an enormous knowledge of how the system worked. This was the start of a long friendship with Diana. During my period, the Foundation must have sent about a 100 scholars from Sri Lanka. They sent some of the best and brightest and many of them had outstanding careers later on. One of the scholars who went to the US was Mrs. Indira Samarasekara, who had obtained a first class in mechanical engineering from Peradeniya. She was exceptionally bright. Later, she was to become the President of the University of Alberta in Canada and arguably the Sri Lankan to reach the highest pinnacles of academic governance abroad.

There was another interesting committee of which I was a member. It was a non governmental body- the Ecumenical Loan Fund (ECLOF), of Sri Lanka, which was an NGO created by the World Council of Churches (WCC), around 1973. Adrian Wijemanna, whom I had known from my days in the Land Commissioner’s Department, was now with the WCC and was responsible for the creation of this new body. It had a modest amount of financial resources, from the WCC in Geneva, and these resources were channelled through ECLOF to small mini-development projects in the country.

Adrian requested me to join the board of ECLOF and the other members of the board included Chandi Chanmugam, Mark Fernando (later Supreme Court judge), Soma Kannangara (President of the Lanka Mahil a Samithi), and a couple of others. It was an interesting experience.

(Excerpted from the writer’s biography, The Long Littleness of Life. Leelananda De Silva. A member of the Sri Lanka Administrative Service from 1960-1978 he was Senior Assistant Secretary and Director of Economic Affairs of the Ministry of Planning and Economic Affairs from 1970 – 1977)

(Editor’s note: We regret that the byline was omitted from last Sunday’s excerpt on the Commonwealth also written by De Silva.)

Features

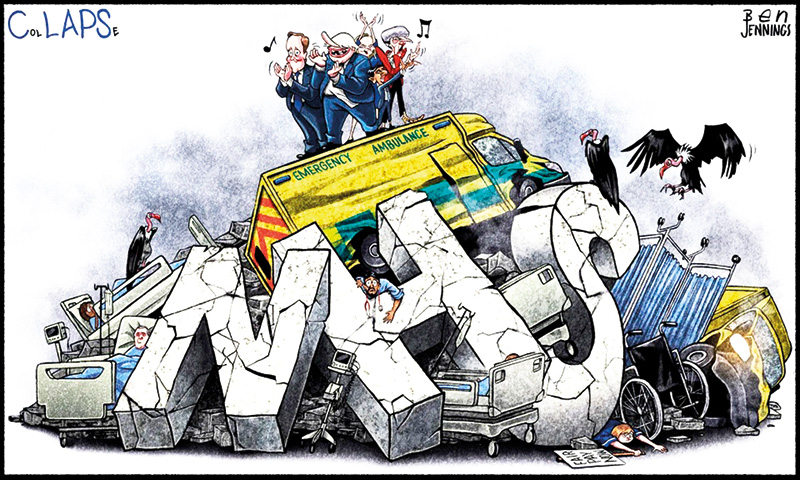

Shock therapy for ailing British NHS?

by Dr Upul Wijayawardhana

That it invariably leads to disaster when politicians attempt to tinker with what they know very little about is well illustrated by what is happening to the British National Health Service (NHS). Unfortunately, the politicians who attempted to reform the NHS over the years, with disastrous consequences, seem to have completely disregarded the aphorism—if It ain’t broke, don’t fix it. Although it is fast heading towards the bottom of the league now, the British NHS once was the best in the world and many countries attempted to emulate it because it was a cost-effective system providing free healthcare to all, irrespective of one’s ability to pay. It stood as a testimony to the socialist foresight of the post-war Labour administration of PM Clement Atlee and his Health Minister Aneurin Beven, considered the ‘Father of the NHS’; he made the ever-true declaration: “No society can legitimately call itself civilised if a sick person is denied medical aid because of a lack of means.”

Although I am not a fan of his, I must admit that Keir Starmer deserves to be lauded for attempting to reverse that trend with his recent announcement. Giving a fillip to his administration, which has been faltering up to now, PM Starmer announced plans to get rid of a resource-draining quango, pointlessly duplicating the work of the Department of Health: NHS England employing 13,500!

Margaret Thatcher seemed very keen to reform the NHS, her motive probably being more political than anything else. She was toying with the idea of introducing a scheme for compulsory health insurance, but her Health Secretary Kenneth Clarke, who was against this idea, persuaded her to introduce a less controversial ‘trust’ system instead, which took hospitals away from the control of District Health Authorities. Despite being a far less successful system, Clarke wanted the UK to ape the Managed Hospital System in the USA! Clarke’s argument was that hospitals needed enhanced management with independence to compete in an internal market and created Hospital Trusts, in stages, beginning in 1990. To anyone with common sense it was a daft idea, especially the concept of hospitals competing with each other, but that is politicians for you! The downward spiral of the NHS started with the trust system and I have no hesitation in referring to this as the ‘Clarke’s Curse’!

Trusts were given further independence with the creation of ‘Foundation Trusts’ and other service providers like ambulance services also converted into trusts during the John Major administration that followed Thatcher’s. Towards the end of this administration a Private Finance Initiative (PFI) was set up where the private sector built hospitals and trusts had to pay back regularly with huge interest, like a mortgage. This scheme was enhanced by the Tony Blair administration, but, unfortunately, became a millstone around the neck later, some trusts having to declare bankruptcy!

Tony Blair, who became Prime Minister in 1997, could have changed direction to save the NHS but instead opted to continue with the Conservative health reforms. Perhaps, his New Labour was more Conservative than Labour! The most significant political change during the Blair administration was devolution of power, leading to the creation of the Scottish Parliament and the National Assembly for Wales in 1997, followed by the creation of the Northern Ireland Assembly in 1998. As health became a devolved subject with these changes, paradoxically, the Health Secretary of His Majesty’s government looks after the health services of England only! However, devolved health systems usually follow the English system but there can be significant differences like the prescription charge. It is only residents of England that pay for their medication, with a fixed prescription charge irrespective of the cost of medication, the current charge being £9.90 per item. Those with exemptions in England as well as residents of the other three devolved nations get all their medication free.

During the disastrous Cameron-Clegg coalition government, the Health Secretary Andrew Lansley decided to give the NHS in England an ‘independent arm’ and NHS England was created in 2013, which currently employs 13,500 staff, three times more than the Department of Health! NHS England is an executive non-departmental public body of the Department of Health and Social Care, which oversees the budget, planning, delivery and day-to-day operation of the commissioning side of the NHS in England and according to its website: “NHS England shares out more than £100 billion in funds and holds organisations to account for spending this money effectively for patients and efficiently for the taxpayer.”

All these reforms made the NHS top-heavy with management and the resources poured by governments went to feed the managers mostly, only dribbles going for patient care, and my experience at Grantham Hospital mirrored what happened across the rest of the country. When I started working at Grantham in 1991, it was a District General Hospital, which has been in existence since 1876, with 300 beds and a large estate with quarters for most employees. It was managed by a General Manager, a Matron, and an Estates Manager. When it became a Trust in December 1994, we had a Chief Executive with Directors in Medicine, Surgery, Nursing, Estates and Operations, all drawing hefty salaries, and many assistants! Later, it joined Lincoln and Boston Pilgrim Hospitals to form the United Lincolnshire Trust. By the time I retired, 20 years later, there were only 100 beds and much of the estate was in the hands of private property developers! Since then, it has become a shadow of its former self: there are no acute beds at all though around 3,000 houses have been built around Grantham during the past two decades. For any acute emergency, Grantham residents must travel to Lincoln, a car journey close to an hour!

Hospital overcrowding has got so bad that many hospital corridors are blocked with beds now. In fact, some hospitals have started advertising for staff to look after patients in corridors! Only thing missing yet are ‘floor patients’, which I presume is an impossibility because of cold floors! In spite of introducing corridor beds, too, patients often have to wait over 24 hours in Accident and Emergency Departments for a bed, lounging in chairs with drips and oxygen tubes! Imagine this happening in one of the richest countries in the world!

One of the biggest drawbacks in UK healthcare is the lack of private emergency care, private hospitals being geared to do elective work mainly. Therefore, even those who can afford to pay are at the mercy of the NHS for emergencies, in contrast to Sri Lanka where emergency care is readily available in the private sector; the fact that even a short stay can bankrupt is a different story!

I may be voicing the fears of the many who are waiting in the ‘departure lounge’ when I state that I prefer death to the ignominy of waiting in chairs or corridors.

Things are so horrible that shock therapy was badly needed. Though he had no choice, it was still brave of Keir Starmer to announce the demise of the redundant, wasteful NHS England. There are claims that job losses will come to nearly 30,000 and cost of the exercise would be in billions of pounds. Perhaps, there is some truth as NHS managers assume duties with water-tight fat severance packages! Even that short-term cost is justified to improve the NHS long-term, as there are no further depths to descend! I can only hope that Starmer’s decision will produce the desired result and, in the meantime.

Features

Neighbourhood Lost: The End is Nigh for SAARC’s South Asian University

Of Man’s First Disobedience, and the Fruit

Of that Forbidden Tree, whose mortal taste

Brought Death into the World, and all our woe,

With loss of Eden …· John Milton (Paradise Lost)

On 26th February 2025, Yashada Sawant, an Indian female student from the South Asian University (SAU), an international University in New Delhi, was publicly assaulted by Ratan Singh, a male student from the same university, along with a gang of goons with clear affiliations to the Akhil Bharatiya Vidyarthi Parishad (All India Students’ Council) a.k.a. ABVP. That ABVP is a right-wing student organisation affiliated to the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS), a known Hindu nationalist organisation in India, is no secret.

On 26th February 2025, Yashada Sawant, an Indian female student from the South Asian University (SAU), an international University in New Delhi, was publicly assaulted by Ratan Singh, a male student from the same university, along with a gang of goons with clear affiliations to the Akhil Bharatiya Vidyarthi Parishad (All India Students’ Council) a.k.a. ABVP. That ABVP is a right-wing student organisation affiliated to the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS), a known Hindu nationalist organisation in India, is no secret.

Their grouse was that fish was being served on Maha Sivaratri and Ms Sawant’s ‘crime’, as the Mess Secretary elected by students to oversee canteen operations, was trying to stop the fish curry from being thrown away by them. This is when the assault ensued, with Sawant being punched in the face and inappropriately touched by these students, who are yet to be punished by the university.

What is of concern is that the university does not have a good track record when it comes to women’s safety. Apoorva Yarabahally, a former legal studies student had earlier lodged a complaint against her Dean of harassment and also described her entire ordeal on X in April 2023. To date, however, the university has failed to take any action.

The university’s canteens have always served both vegetarian and non-vegetarian food. On the day in question, special arrangements had also been made for those observing the religious holiday. While there have often been on-and-off caste-based arguments over the ‘purity’ of food, this has never reached the depths of the recent incident. Sadly, this is not a freak mishap.

Since SAU’s current India-nominated President A.K. Aggarwal, who has no experience in running an international university, took over, his tolerance and even sponsorship of absolute parochialism, especially where the Hindutva agenda is concerned, has led to this deplorable state of affairs.

In her recent detailed tweet, Sawant has clearly described the role of different university officials who have attempted to sweep numerous sexual harassment complaints under the carpet. The same Proctor, who was reprimanded by the Delhi High Court in an earlier case for not following SAU regulations, still holds the reins and has been instrumental in pushing the overtly misogynistic agenda in SAU.

SAU’s South Asian sensibility dismantled

SAU was established by the South Asian Association for Regional Cooperation (SAARC) as an international university in 2010 with taxpayer’s money from all eight member countries. Therefore, the legal and institutional ownership of the university is with SAARC.

It was meant to be a secular, English language university where no single political ideology, language or any one form of nationalism was to dominate. Its founding provisions and principles were meant to preserve the university’s South Asian character. The intention of the university’s founders was to bring in an element of parity and equality in the broader space of inequity and hegemony in which the university is physically located.

Unfortunately, notwithstanding these laudable efforts, a mere 15 years into its establishment, the downward spiral of the institution is driven by the incumbent president, with alarming signs of an imminent and total crash.

The bottom line is, SAU is no longer effectively owned by SAARC and it is certainly not South Asian by any stretch of the imagination. In cultural and social outlook, it has become blatantly North Indian, to the extent that it is even making students from other regions in India feel extremely unsafe.

While Aggarwal and his handpicked coterie of yes-men and women are dismantling the institution, its academics have hypocritically stood by in tacit support, pusillanimously hiding behind lofty pronouncements in the regional and global conference circuit. Its feminists who call themselves ‘critical feminists’ have fallen silent.

With an overwhelmingly Indian student body at present and very few non-Indian officers in administration, the university has become a largely Indian entity. Among others, the proctor of the university, dean of students, registrar, directors of various departments, deans and department heads and almost all non-academic staff are Indians.

The mandatory student ratio with 50% being Indian and the rest from other South Asian countries, has been breached with the introduction of new India-oriented courses (such as BTech degrees) and the expansion of all intakes benefiting mostly Indian applicants. From 2024 onwards, non-Indian students have been reduced to mere spectators on campus.

This could be the final nail in the coffin for the university’s South Asian Character.

SAARC & SAU Governing Board’s Culpability

As a formal intergovernmental effort in New Delhi, the university’s rapid parochialisation is a telling example of the utter ineffectiveness of both SAARC and SAU’s Governing Board members representing the eight SAARC countries.

The brick-by-brick dismantling of the institution, that held considerable promise until seven years ago, is propped up by their lackadaisical attitude. By extension, this foreshadows the trajectory of what the Indian government claims to be its main vision and strategy in the region – the Neighbourhood First Policy – and is more like the figurative ‘fist’ in the neighbours’ faces.

The manner in which SAU marks the national days of the SAARC member states clearly exemplifies the path it is treading. Until December 2023, national days were not in the university’s calendar of events. Students from different countries, on their own volition, celebrated these occasions of national importance without any involvement of university administration. This was to consciously maintain a distance from politically sensitive occasions in the larger interest of preserving the university’s multinational character.

Aggarwal’s decision to make the national days part of the university’s calendar initially appeared to be a progressive step towards cartographically recognising South Asia. But as it ensued, only India’s Independence and Republic Days were celebrated with pomp and pageantry and the SAU President’s personal participation.

After he initiated this practice by celebrating India’s Republic Day in January 2024, Sri Lanka’s Independence Day which fell a week or so later, was not marked in any manner. I brought this to the attention of the then Sri Lanka High Commissioner in New Delhi. Neither Sri Lanka nor any other diplomatic mission in Delhi with citizens in SAU has shown any interest in rectifying this lapse. Since then, only political events important to India are being celebrated.

I recall suggesting to Aggarwal, it would be best to help minority nationalities observe their national days with university sponsorship, if this was indeed the declared policy of the university, or to stay away from such celebrations altogether in line with the past practice. But this advice was not heeded. My intention in making this suggestion was to establish inclusiveness and not institutionalize exclusion. It is evident, the latter is now the norm, a legacy which no discerning or self-respecting leader or institution would wish to leave behind.

SAU as a Hindi Language and Hindu Enclave

SAU has also become an unapologetic Hindi Language enclave, further crippling the South Asian character of the university. When the International Mother Language Day was celebrated at the university on 21st February 2025, a North Indian student wrote ‘Jai Sri Ram’ on a Tamil poster put up by Indian and Sri Lankan Tamil speakers, leading to a needless scuffle.

The occasion had been peacefully and gracefully celebrated at the university since 2011 until recent times, when every language spoken at the university was celebrated by its speakers, and their histories and literatures brought to the fore. This was a practice introduced by Bangladeshi students and embraced by all others.

The new language chauvinism does not operate in isolation. It is manifesting itself in a situation when the three-language formula of Independent India has effectively been disregarded by the present government. As anticipated, this already led to the reemergence of language nationalism as a counter force in southern states.

Students also do not feel comfortable in approaching the Dean of Students Navnit Jha, who only speaks fluently in Hindi, and whose office has been compromised due to his track record in harassing students who are considered ‘too independent’.

One of the salient features of the current administration is the weaponisation of the offices of the Dean of Students and Hostel Wardens and the deafening silence of the Gender Sensitisation Committee. They have been successful in silencing students with the everpresent threat of expulsion. The same threats to faculty have also succeeded spectacularly, with the suspension of four faculty members in 2023.

Hindi hegemony appears on many other fronts too. SAU’s sports festival this year is called ‘Khel Kumbh’, the word kumbh being written in Hindi on all official posters shared on social media. Khel means sports in Hindi.

Would it not have been more inclusive if the word had been adopted from one of the minority languages represented in the university’s student body? Why not kreeda in Sinhala; viḷaiyâṭṭu in Tamil; Khçlâdhulâ in Bengali; kaayikam in Malayaam and so on? This is one way in which people can be brought into the fold rather than by suppressing them with hegemony.

One should either use only English for such events and posters or the different South Asian languages represented in SAU for different events. But this can only be conceived by a leadership with intellectual sophistication.

In the same way, the word kumbh is also problematic, given its religious connotations with Hinduism via the Indian state sponsored Kumbh Mela in Allahabad. But this is the SAU administration’s ruse to signal to the government that it is looking after its interests given the way the latter has lately culturally upended this important religious festival.

Surely, there would have been many ways to conceptualise and name this sports event and many other university events within the cultural and linguistic plurality India and South Asia have to offer.

But this is not the only association SAU has with Hinduism officially. While freedom of faith existed in SAU, from its inception, it did not involve itself in religion. This very sensible approach was adopted by the two earlier presidents though both hailed from a Hindu background. My own position was that the university can have a dedicated space or spaces for worship for those who required them, while not sponsoring events or ideas belonging to any particular faith. My views came from a more open approach towards faith emanating from my own training and upbringing. But I was overruled on the basis that such openness would lead to intractable inter-religious competition and potential hegemony. They were clearly drawing from their own experiences in India. And seeing what SAU has become, I appreciate my senior colleagues’ foresight at the time. Such enlightenment is no longer prevalent in SAU.

Today, for all intents and purposes, SAU is a Hindu organisation. Though in theory, the university is not supposed to have dedicated places of worship, in practice the situation is different with a shrine informally set up in ‘Block A’, one of the hostel areas for students. But interested staff and faculty also freely visit this place. Though this is known, no opposition has been voiced, which is in effect tacit encouragement for the institutionalisation of Hinduism. If so, why not similar spaces for Jainism, Sikhism, Buddhism, Islam and Christianity which are all major faiths in the SAARC landscape and in the university too?

The situation gets worse: For an institution that hitherto has intentionally stayed away from sponsoring religious events, it does now just as consciously. On 19th February 2025, Lila Prabhuji, in collaboration with the educational wing of International Society for Krishna Consciousness (ISKCON), Delhi.

Moreover, the community dance typically associated with ISKCON activities was enacted with the active participation of faculty, staff and students. This can certainly be a regular practice if need be, but it would be non-discriminatory, only if the university also sponsors events by other religions and allows them the same space to practice aspects of their faith as well. This, however, is not the case.

These are just a few well-known examples. But the rot runs deeper, even into the dubious recruitment of teachers and new teaching program designs. Moreover, new ‘professorial’ recruits who are running newly established centres and schools such as the Faculty of Arts and Design and the Centre on Climate Change do not have serious academic credentials. Their academic trajectory of having worked in dozens of institutions of no great repute raises questions about their ability to initiate these centres and schools.

But significant scholarship on these areas have been produced across South Asia. For instance, Arts and Design are fields where Pakistan, Sri Lanka and Bangladesh have excelled in and produced good scholars. They were not even considered for positions in SAU. Moreover, Delhi itself has reputable institutions in these fields from JNU’s School of Arts and Aesthetics to College of Arts, from where well-trained academics or recent graduates could have been recruited.

It is evident that the administration is not interested in placing emphasis on academic rigour or established scholarship. Instead, it is looking for people it thinks can be controlled rather than seeking to benefit from their intellect and experience. This effectively results in the relentless pursuit of mediocrity, entrenchment of yes-men and women, compromising the future of the university in much the same way many other major universities in India have been in recent times.

One could argue, this downward spiral is contained within SAU and is not a reflection of the Indian government, the university’s Governing Board, or the SAARC Secretariat in Kathmandu. But this would not be a valid proposition. India is the only country that has had representation within the university for many years through a staffer of its Ministry of External Affairs. Hence, the Indian government is well aware of the situation in the university, and it’s wishes and diktats are often informally communicated to the SAU administration.

No other country has been accorded this privilege. Moreover, the responsibility of the Governing Board and the SAARC Secretariat is to ensure that the university is run according to the norms, rules and regulations which have already been collectively designed, approved and established, in the interest of the member states.

Regrettably, one cannot see this expected oversight from these mechanisms. Governing Board meetings are effectively mere rituals of scant significance, where members simply fly in from their respective countries for a free foreign trip and a few hundred US dollars per head. No one other than Indian representatives makes any contribution of substance. India for its part, dictates while the rest nod in uniform agreement.

The SAU administration’s self-assuredness in their illegalities and arrogance emanate partly from this situation where it is guaranteed protection by the Indian government come hell or high water, and there is silence from the rest of the board. This also comes from the fact that no other country other than India pays their dues at present, and that too in relatively smaller amounts. This institutionalised ‘loss of face’ by being cash-strapped does not help; nor does the resultant sense of superiority of India.

This combination does not augur well for the professional running of an institution, much like the United Nations which is driven by the vested interests of the five permanent members of the UN Security Council (P5) and the organisation’s major contributors.

If SAARC does not own up to its own creation, it should move away from SAU as should all member states so that the undeserving reputation the university is given by this association is formally and legally severed. Hapless students will thus not be misguided to an institution in search of a South Asian enclave in Delhi, and be marginalized and isolated in a toxic space, and end up being victims of the callous lack of regard and interest of their own Governing Board representatives.

On India’s part, it would behoove the government to legalize the de-facto hostile cultural and political coup that has already been allowed to take place. It can graciously do so by formally handing over the funds other member states have already poured into the university since inception. In fact, at an early stage of this de-facto transition, I made this very suggestion to Ramesh Chandra, an MEA functionary who had been appointed Acting President.

I proposed that he communicates this to the Indian government so that the pretense of SAU’s South Asianism can formally end and people like me who had come to Delhi to set up a very different institution can go back home in peace knowing we tried but failed due to India’s Big Brother attitude and other regional governments’ pusillanimity in countering this in an institution they collectively set up.

As far as the rest of South Asia is concerned, SAU should simply be left to its own desires, designs and devices — a mediocre and parochial institution spewing venomous cultural and nationalist ideologies. Let it be another case study of a grand idea doomed for failure, much like the Nalanda University, because of unchecked singular and toxic nationalism. The danger however, is its spillover effect on the neighbourhood, and the potential disruption of regional harmony. This also shows that South Asian countries, including India are incapable of managing a truly international university. The required cosmopolitanism of thought and outlook are absent, and these nations need to accept this reality.

—-

(An earlier version of this essay appeared in The Wire on 8 March 2025).

Features

The Case of Karu Jayasuriya – II

By Rohana R. Wasala

(Continued from Friday, March 7, 2025)

Leaders should lead us as far as they can and then vanish. Their ashes should not choke the fire they have lit. H.G. Wells (1866-1946)

Part I of this article ended with the following two sentences: “When countries are unequal partners, the weaker nations become subject to various forms of subversion (political, economic, cultural, etc.,) exerted by the stronger nations. Willing submission to international subversion seems to be Jayasuriya’s creed”.

The last sentence might be offensive to those who admire the veteran politician, though I am one among them, too. Let me be clear. The operative or the key word in the last sentence is ‘seems’, which prevents it from being a charge levelled against Jayasuriya. He is definitely not guilty of such betrayal of the national interest. His apparent giving in to unwelcome camouflaged foreign interventions and interferences, attempted through aid programmes, is not the reality. It is only an impression. It is not certainly a systematic mode of managing development assistance (received from foreign agencies for the benefit of all the citizens) that he is religiously committed to. We have to appreciate the fact that giving such an impression as a pragmatic accommodation of donor wishes is a necessary evil, for the funds and other forms of help received are welcome, and cannot, and should not, be refused as long as they are available.

As Shamindra Ferdinando pointed out, under the subheading ‘KJ’s USAID project’, in an earlier feature article in The Island, entitled “Costly UNDP ‘lessons’ for Sri Lanka Parliament”/June 22, 2023, the USAID launched in November 2016 a three-year partnership with Parliament, estimated at SLR 1.92 billion (US $ 13 million at the exchange rate of the time) to ‘strengthen accountability and democratic government’ in the country. According to the same article, a US Embassy statement quoted USAID Mission Director Andrew Sisson at the time as having said ‘This project broadens our support to the independent commissions, ministries, and provincial and local levels of government’. This was based on an unprecedented agreement between the USAID and Parliament finalized in 2016. Ferdinando correctly observed in this piece, written almost two years ago, that the USAID projects in Sri Lanka correspond to their much touted free Indo-Pacific concept, which means, in other words, countering growing Chinese influence in the region.

It is unlikely that Karu Jayasuriya is unaware of these facts.

We, senior Sri Lankans wherever we live in the world at present, know that American aid agencies have been active in our country even from before the USAID was established in America in 1961. I well remember how, as schoolchildren in our pre-teens in the late 1950s, we were given milk to drink as part of our free mid-day meal. The milk was made from milk powder provided under the American CARE organization (Cooperative for Assistance and Relief Everywhere). The crying need at the moment is for those projects to be looked into and suitably managed free from corruption for the good of the general public, without compromising our national sovereignty and self-respect (the only two treasures that, as the late great patriot Lakshman Kadirgamar said, we still possess and should never abandon).

A young independent investigative journalist (obviously with national interest at heart), writing on her website (March 1, 2025), gives the link to access the ChatGPT list of US agencies funding government and civil society entities operating in Sri Lanka 2015-to date (It is freely available on the web for anyone interested to check out, so naturally she won’t like or expect to be identified as making a special revelation). The list categorises the recipient entities, names the relevant USAID agencies, records the funding amounts, and states the programme focuses and the dates. She demands that the government launch an immediate investigation and disclose the truth to the Sri Lankan citizens, a call that we should all join in. It is unfortunate that a bunch of half-baked YouTuber ‘journalists,’ with political axes to grind, pounced on the well meant alert of the young authentic journalist as an opportunity to ‘score hits’ on their channels and increase their dollar income.

USAID agencies have implemented countless development projects in many countries across the world, including Sri Lanka, for over six decades now. As lawful and legitimate programmes, they employ thousands of poor people, providing livelihoods for them. Before stopping the funds, if they must, such affected innocents will have to be looked after and found some compensation. It has already been suggested that President Trump’s moves are likely to be legally challenged in America for this and other reasons. For, whatever happens, the ultimate sufferers will be the poor wherever they happen to be.

As for Sri Lanka, it remains a poor indebted nation after 77 years of heavily qualified (22 years of dominion status + 53 years of fuller) independence. This is not for lack of undaunted patriotic striving after national unity, communal peace and economic prosperity for all citizens through overall comprehensive development by the democratic majority of multiethnic Sri Lankans while facing unavoidable manipulative foreign interventions and interferences, and internal resistance fed by such hegemonic forces. None of the three powers besieging us can be ignored or discounted. Maintaining a proper balance between them without aligning with a specific one among them is always work cut out for political handlers of Sri Lanka’s foreign policy matters. That is an unenviable task that confronts both the parliamentarians and civil servants involved. Judicious, efficient and corruption-free running of foreign aid projects for the mentioned purpose of holistic national development is the need of the hour.

Karu Jayasuriya seems to envision the goal of answering that need, though obviously he is too old to play an active role in achieving that goal. His inspiring mentorship will be of help. He has a history of rising to the occasion when push comes to shove in resolving national issues. In 2007, when the UPFA government, under Mahinda Rajapaksa, was struggling to survive against the underhand dealings of the UNP’s Mangala Samaraweera with the separatists and the JVP’s non-cooperative stance. MR wanted to push the Humanitarian Operation against the separatists to its victorious end. Jayasuriya crossed over to the government side with 17 fellow front-liners of the UNP opposition. Jayasuriya’s timely move paid off. It saved the MR government, and in another two years they saw the end of separatist terrorism. So, Jayasuriya played a heroic role in that situation.

Karu Jayasuriya claimed that the 2015 regime change would not have become a reality but for the leading role played by the National Movement for Social Justice (NMSJ) of which he was a prominent member. The original name of the campaign launched by the late Ven. Maduluwawe Sobitha Thera, the Chief Monk of the Naga Viharaya of Kotte, was the ‘National Movement for a Just Society’ (NMJS). Jayasuriya followed the much respected leading Buddhist monk, a committed patriot, as the organisation’s head after the latter’s unexpected death on November 6, 2015 at a Singapore hospital, aged 73.

A pro-regime-change website of the time (most probably sponsored by a foreign funder), paying a memorial tribute, described him misleadingly as “the monk who ended Sri Lanka’s decade of darkness”. In reality, of course, the 10-year period (2005-15) saw the end of three decades of terrorist violence and the highest economic growth rate ever achieved during that time amidst numerous challenges, and these achievements were made by the nationalist forces that Ven. Sobitha had made common cause with in opposing the neoliberal policies of the West-oriented United National Party (UNP) led by president J.R. Jayawardane, from 1977 to 1988, undergoing even physical harassment in the process. A Sri Lanka-born anthropology professor, trained in America, wrote in an article following his death that the monk was ‘a nationalist turned democratic activist’, wrongly equating nationalism with absence of democracy and representing it as a reactionary force.

Unfortunately, the poor professor was adopting the American definition of ‘nationalism’, which is what you find in the Google Dictionary: ‘identification with one’s own nation and support for its own interests, especially to the exclusion or detriment of the interests of other nations’. There is a subtle substitution of nation for race. So this definition fits racism, which we all know is primitive and reprehensible. Ven. Sobitha used ‘nation’ to mean all the people living in the country, not exclusively the Sinhalese Buddhists. So to try to denounce the monk as a ‘nationalist’ in the American sense was not right.

Be that as it may. This is no time to further contest the learned professor’s assessment of the upright nationalist Ven. Sobitha who rose up against the war-winning President Mahinda Rajapaksa when he concluded that the latter, in the flush of victory, had turned authoritarian and was not doing what he had pledged to do as a true nationalist (i.e., in the non-American sense). He disliked the imprisonment of Sarath Fonseka, the General who played the pivotal role in defeating separatist terrorism, and agitated for his freedom. The monk also thought that the executive presidency was a problem and became an advocate of its abolition, which was not very wise.

At this point, unfortunately, Ven. Sobitha was discovered by the foreign-funded regime change agents who had been able to split the victorious nationalist camp, exploiting flaws in MR’s leadership, as ripe for being ensnared into their plot. He soon became the most influential supporter of Maithripala Sirisena as the common candidate of the Opposition. The monk didn’t know that he was participating in a conspiracy without his knowledge. According to Mahinda Rajapaksa, who visited him (presumably, when in hospital) after the 2015 regime change, the monk admitted having been misled by the Yahapalana campaigners. That does not redeem MR. We know that Jayasuriya figured prominently in that camp and had become a fair critic of Rajapaksa for the same reasons as the less worldly wise Ven. Sobitha, though he had earlier helped him to defeat the terrorists.

At the inauguration of the Institute of Democracy and Governance (IDAG), his brainchild, in Colombo on September 30, 2024, Jayasuriya spoke about the alienation of our current political leaders from the noble values espoused by leaders such as D.S. Senanayake, Don Baron Jayatilake, and their successors. Pursuit of self-interest seems to be more important to our current political leaders than serving the public and scandals often damage their reputation, he said. In a newspaper article written to mark the launch of the IDAG on September 30th last year, a day after his 84th birthday, Jayasuriya’s daughter Lanka Jayasuriya Dissanayake, a UK qualified doctor, holding a position in WHO, Sri Lanka as a National Professional Officer, wrote:

‘(The IDAG) … initiative serves as both a celebration of his lifelong commitment to democratic values and as a gift to the nation—a pathway toward building a generation of leaders with the caliber and integrity that Sri Lanka desperately needs’.

The time for active politics is gone for Karu Jayasuriya as it is for many others of his era whose names will spring to your mind. Unlike some of them, however, he has something special to teach the young patriots engaged in politics. So, his assumption of a mentorship role, without just vanishing after having done his duty as a leader, as the great H.G. Wells suggested, is eminently appropriate for these critical but promising times.

To be concluded

-

Foreign News2 days ago

Foreign News2 days agoSearch continues in Dominican Republic for missing student Sudiksha Konanki

-

News6 days ago

News6 days agoAlfred Duraiappa’s relative killed in Canada shooting

-

Features5 days ago

Features5 days agoRichard de Zoysa at 67

-

Editorial7 days ago

Editorial7 days agoGhosts refusing to fade away

-

Midweek Review6 days ago

Midweek Review6 days agoRanil in Head-to-Head controversy

-

Features5 days ago

Features5 days agoSL Navy helping save kidneys

-

Features7 days ago

Features7 days agoThe Gypsies…one year at a time

-

Latest News3 days ago

Latest News3 days agoDebutant Madara, Athapaththu fashion Sri Lanka women’s first T20I win in New Zealand