Features

Comparative study of Boeing and Airbus – Part I

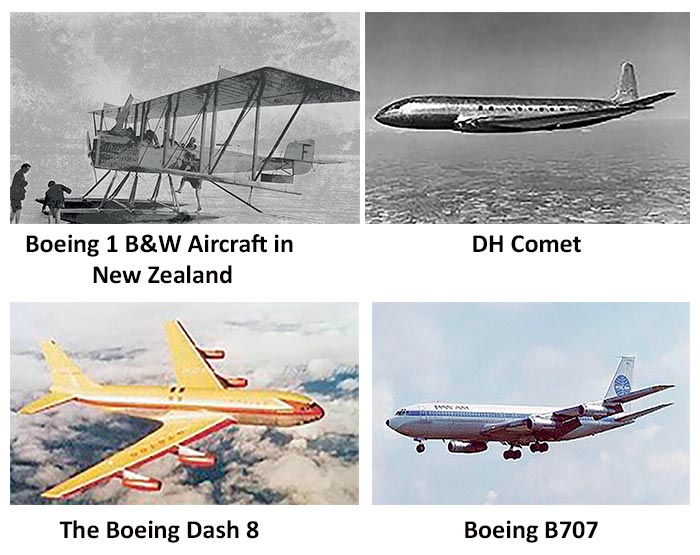

With the tragic accident of Air India Flight 171 at Ahmedabad on June 12, 2025, the focus has fallen on safety and reliability of jet aircraft in general, and the Boeing 787 Dreamliner specifically. Other aspects of that event aside, there is a probably little-known nexus between Air India and Boeing aircraft: In 1962 India’s flag-carrier became not only the world’s first all-jet airline but also the first jet-equipped airline in Asia when it began operating a fleet of Boeing 707-420 aircraft

Today, Boeing and Airbus are the world’s two leading manufacturers of commercial airplanes. But those companies’ histories are diverse in terms of their origins – in Boeing’s case spanning nearly 110 years – and evolution. This article seeks to explore those manufacturers’ stories and products in some detail

Introduction

William E. Boeing was born in Detroit, Michigan, in 1881, to an Austrian mother, Marie Ortmann, and German father, Wilhelm Böing. When his father died in 1890, nine-year-old William moved to Europe with his mother and sister. After the widowed Marie remarried, she returned to the USA with her son (now known as William Boeing) and daughter.

Having enrolled in Yale University’s Sheffield Scientific School in 1898, William Boeing dropped out in 1903 to enter the lumber business in the Pacific Northwest of Washington state, an industry in which his father had made a modest fortune. Not to be outdone, the younger Boeing also prospered on the strength of a construction boom, shipping lumber to the USA’s east coast, via the newly-built Panama Canal.

However, in 1914, William and a friend, Conrad Westervelt, became interested in flying machines. A joy flight with an itinerant barnstormer pilot in 1915 inspired them to build their own airplane. But before constructing an aircraft they had to learn to fly. So the pair took flying lessons at the Glenn L. Martin flying school in Los Angeles, California, and bought their first flying machine, a Martin seaplane.

Back home in Washington, following a flying accident that necessitated repairs to their seaplane, Boeing and Westervelt discovered that Martin, the manufacturer, was unable to supply the spare parts required in a timely manner. Not content to wait, they decided to start building their own parts. Their original company, called B & W, consisted essentially of a boathouse on the edge of Lake Union, near downtown Seattle. But with the advent of World War I, Westervelt was mobilised by the US Navy and moved out. Left to his own devices, Boeing hired a highly-recommended and -qualified Chinese engineer named Wong Tsu (a.k.a. T. Wong).

With Wong’s assistance, the first B & W seaplane, designated Boeing Model 1, was ready to be test-flown by June 1916. There were already 21 workers on the payroll, and in July that year the company was incorporated as the Pacific Aero Products Company, with William ‘Bill’ Boeing as its President.

Eventually, the Boeing Aircraft Company, as it was later renamed, procured an order from the US Navy for 50 Model C trainer seaplanes. The company even exported two B & W seaplanes to the New Zealand government, thus recording Boeing’s first overseas order for his products.

More success followed in 1918 with a sub-contract for Boeing to build 25 flying boats for the US Navy. These aircraft were, however, designed by the Curtiss Aeroplane & Motor Company, and designated as HS-2L patrol flying boats. Bill Boeing was so impressed with this design that he improved on it and produced the C 700 aircraft, to carry mail from Vancouver, Canada, to Seattle. This was the first international airmail to the USA, on March 3, 1919.

Meanwhile, in Britain, another aircraft manufacturer, who would achieve worldwide fame, was beginning to make his mark. The company he founded in 1920 would be instrumental in the formation, much later, of the giant European aerospace conglomerate that is known today as ‘Airbus Industrie, or simply ‘Airbus’. That British aviation pioneer was Geoffrey de Havilland, who, after working for the Wolseley and Austin motor car companies, designed and built his first aircraft in 1909 while teaching himself to fly.

Joining the Royal Aircraft Factory at Farnborough as a designer, where much of the emphasis was on kites and balloons, de Havilland succeeded in selling experimental aircraft of his own design to the factory. But a turning point in de Havilland’s fortunes occurred when, a year before WWI, he joined a company called Airco, where he designed many types of aircraft for the Great War, including a bomber named the D.H.4. Although dubbed the ‘flaming coffin’ by pilots, the D.H.4 was de Havilland’s first major success, and by 1917 the company was manufacturing 300 Airco D.H.4s per month. From a total production figure of 6,295 aircraft, nearly 4,900 were built under licence in the USA, many of which were used on airmail services in that country.

For its part, Boeing in the USA suffered setbacks for want of customers after the Great War, but managed to keep producing new models on an average of two types per year, supplying demand from the military and airlines such as Pan Am and TWA.

Remaining with Airco after the war, Geoffrey de Havilland, a prolific and innovative engineer, was responsible for more than 20 new designs, with type numbers from D.H.1 to D.H.21, although some were never built. Among the successful types were a D.H.9 converted to carry four passengers, and the eight-passenger D.H.18 in 1920. That was also then when Geoffrey de Havilland left Airco to establish his own de Havilland Aircraft Company.

The period between the two World Wars came to be known as the ‘Golden Age’ of aviation on both sides of the Atlantic. In what was a ‘technological push’ de Havilland sought to make aviation attractive and affordable to the general public for military and civil transportation within Europe.

Boeing, on the other hand, concentrated most of its energies on building military airplanes. With the advent of World War II, large numbers of Boeing B-17 Flying Fortress and B-29 Superfortress bombers were built. On the other side of the Atlantic, de Havilland, too, was involved in the war effort. The D.H.82 Tiger Moth became the basic trainer of the Royal Air Force, while the twin-engine D.H.98 Mosquito, constructed mostly of wood – thus earning the nickname ‘Wooden Wonder’ – proved formidable in a variety of roles, especially as a fighter-bomber.

After WW II, as in the wake of WW I, both Boeing and de Havilland (DH) suffered a drop in business. Despite Boeing having to discontinue the services of more than 70,000 employees, and in keeping with the agreement dictated by ‘world powers’ on the distribution of limited military orders after the war, the US company, along with other American manufacturers, concentrated on building large bombers and troop carriers. Meanwhile the British focused their attention on small fighters.

But Boeing was also notable for producing the Model 377 Stratocruiser double-decked intercontinental airliner, a civil version of the C-97 Stratofreighter military transport and its airborne refuelling tanker derivative, the KC-97 Stratotanker, all derived from the basic design of the B-29 bomber.

But while nearly all Boeing aircraft manufactured thus far were powered by ‘old-fashioned’ piston-engines, the British had acquired more experience and some success with jet engines. So, in its need to compete with the Americans in commercial aviation, in 1942, the British government instituted the Brabazon Committee, named after former Minister of Aircraft Production, Lord Brabazon, to explore and design new types of transport aircraft, including jet-propelled airliners.

Into the Jet age

With experience gained from its successful D.H.100 Vampire fighter jet, which first flew in 1943, de Havilland proceeded with development of what would become the world’s first jetliner, the D.H.106 Comet.

With its revolutionary new airplane cleared for passenger services in May 1952, de Havilland was nevertheless still treading uncharted technological territory by venturing into high-speed, high-altitude, pressurised flight. Indeed, as the unchallenged, first-to-market, technological leader, the Comet was still not a fully tried and tested product. Unfortunately, that lead didn’t last long, because during the first year of Comet service, with Colombo, Ceylon, as one of its destinations, there were three serious crashes.

After preliminary investigation, the type was cleared to fly again, only for another serious and fatal crash to occur in 1954, following which all Comets were grounded indefinitely.

Earlier, the then President of Boeing, William ‘Bill’ Allen, and a company designer Maynard Pennell, had watched with interest when the Comet prototype was shown off at the 1950 Farnborough Air show in 1950. Having conceded leadership in the ‘jet race’ to de Havilland and the UK, Boeing decided to improve on the de Havilland design in producing its own, first passenger jetliner.

With the grounding of the Comets, Boeing were afforded some breathing space. Benefitting from experience with its B-47 Stratojet, a six-engine bomber, and the eight-engine B-52 Stratofortress, Boeing began design and production of a four-jet military transport, the prototype of which was designated the Model 367-80, or ‘Dash 80’ for short. That successful design led eventually to the Boeing 707 jetliner.

Following design revisions and lessons learned from the disastrous de Havilland Comet 1 crashes of 1953 and 1954, the much-improved, sleeker Comet 4 emerged in 1958, in time to earn the distinction of operating the world’s first trans-Atlantic jetliner service. But the Comet 4 carried a relatively small number of passengers, and was designed to operate mainly to remnants of the already dwindling British Empire with their short runways in ‘hot-high and-humid’ climatic conditions.

On the other hand, the Boeing 707 had a larger passenger payload, and soon overtook the Comet on the Atlantic run, proving much more popular and even economical to operate than its British competitor. The 707’s success was even more remarkable in the face of competition from other new US-built jetliners, such as the Douglas (later McDonnell Douglas) DC-8 and Convair 880 and 990 Coronado. Much later, when Air Lanka was founded in 1979, its first two airplanes were Boeing 707s, procured from Singapore Airlines.

Meanwhile, services to those other African and South Asian destinations with runway and climate limitations, as well as to shorter runways in the USA, had to wait until airports extended their runways and improved facilities to accommodate the new generation of ‘big jets’. To counter some of the challenges at home, Boeing built a shorter version of the 707, the 720, to operate shorter regional flights from shorter runways. As expected, the 720 proved popular with many US ‘majors’, such as United Airlines, American Airlines, Braniff International Airways, Continental Airlines, Western Airlines, etc.

As ‘big-jets’ spread far and wide as the choice of long-distance airliner for major and not-so-major airlines all over the world, a need arose for shorter-range jet airplanes to serve regional and even domestic routes in large countries like the USA and Canada, as well as Europe.

Thus were born airliners such as the Caravelle twin-jet, from the Sud Aviation conglomerate in France, the three-engined de Havilland D.H.121 Trident, later known as the Hawker Siddeley 121 Trident (Air Ceylon operated a single Trident bought brand-new in 1969), and from the drawing boards of Boeing another hugely successful type, the Boeing 727 tri-jet.

In Europe, the British government encouraged the consolidation of its many aircraft builders, resulting in the formation, in 1960, of the British Aircraft Corporation (BAC), with a later incarnation of the ‘old’ de Havilland company as one of its components. This company later merged with Sud Aviation in 1962 to design and produce the supersonic Concorde airliner.

Despite the publicity attached to the Concorde then and even today, it was not the first aircraft built to fly faster than the speed of sound in public service. That distinction goes to the Soviet-built Tupolev Tu-144, an almost lookalike (copy?) of the Concorde that was dubbed ‘Concordski’ in the West. The latter aircraft began operating scheduled passenger and freight services in 1975, followed by Concorde only in 1976. (To be continued)

by Capt. G. A. Fernando ✍️

gafplane@sltnet.lk

RCyAF/ SLAF, Air Ceylon, Air Lanka, Singapore Airlines Ltd and SriLankan Airlines.

Types Flown: DH Tiger Moth, DH Dove, HS 748, Boeing B707, B737, B747, Lockheed L1011, Airbus A320, A340 and A330

Features

Why Sri Lanka Still Has No Doppler Radar – and Who Should Be Held Accountable

Eighteen Years of Delay:

Cyclone Ditwah has come and gone, leaving a trail of extensive damage to the country’s infrastructure, including buildings, roads, bridges, and 70% of the railway network. Thousands of hectares of farming land have been destroyed. Last but not least, nearly 1,000 people have lost their lives, and more than two million people have been displaced. The visuals uploaded to social media platforms graphically convey the widespread destruction Cyclone Ditwah has caused in our country.

The purpose of my article is to highlight, for the benefit of readers and the general public, how a project to establish a Doppler Weather Radar system, conceived in 2007, remains incomplete after 18 years. Despite multiple governments, shifting national priorities, and repeated natural disasters, the project remains incomplete.

Over the years, the National Audit Office, the Committee on Public Accounts (COPA), and several print and electronic media outlets have highlighted this failure. The last was an excellent five-minute broadcast by Maharaja Television Network on their News First broadcast in October 2024 under a series “What Happened to Sri Lanka”

The Agreement Between the Government of Sri Lanka and the World Meteorological Organisation in 2007.

The first formal attempt to establish a Doppler Radar system dates back to a Trust Fund agreement signed on 24 May 2007 between the Government of Sri Lanka (GoSL) and the World Meteorological Organisation (WMO). This agreement intended to modernize Sri Lanka’s meteorological infrastructure and bring the country on par with global early-warning standards.

The World Meteorological Organisation (WMO) is a specialized agency of the United Nations established on March 23, 1950. There are 193 member countries of the WMO, including Sri Lanka. Its primary role is to promote the establishment of a worldwide meteorological observation system and to serve as the authoritative voice on the state and behaviour of the Earth’s atmosphere, its interaction with the oceans, and the resulting climate and water resources.

According to the 2018 Performance Audit Report compiled by the National Audit Office, the GoSL entered into a trust fund agreement with the WMO to install a Doppler Radar System. The report states that USD 2,884,274 was deposited into the WMO bank account in Geneva, from which the Department of Metrology received USD 95,108 and an additional USD 113,046 in deposit interest. There is no mention as to who actually provided the funds. Based on available information, WMO does not fund projects of this magnitude.

The WMO was responsible for procuring the radar equipment, which it awarded on 18th June 2009 to an American company for USD 1,681,017. According to the audit report, a copy of the purchase contract was not available.

Monitoring the agreement’s implementation was assigned to the Ministry of Disaster Management, a signatory to the trust fund agreement. The audit report details the members of the steering committee appointed by designation to oversee the project. It consisted of personnel from the Ministry of Disaster Management, the Departments of Metrology, National Budget, External Resources and the Disaster Management Centre.

The Audit Report highlights failures in the core responsibilities that can be summarized as follows:

· Procurement irregularities—including flawed tender processes and inadequate technical evaluations.

· Poor site selection

—proposed radar sites did not meet elevation or clearance requirements.

· Civil works delays

—towers were incomplete or structurally unsuitable.

· Equipment left unused

—in some cases for years, exposing sensitive components to deterioration.

· Lack of inter-agency coordination

—between the Meteorology Department, Disaster Management Centre, and line ministries.

Some of the mistakes highlighted are incomprehensible. There is a mention that no soil test was carried out before the commencement of the construction of the tower. This led to construction halting after poor soil conditions were identified, requiring a shift of 10 to 15 meters from the original site. This resulted in further delays and cost overruns.

The equipment supplier had identified that construction work undertaken by a local contractor was not of acceptable quality for housing sensitive electronic equipment. No action had been taken to rectify these deficiencies. The audit report states, “It was observed that the delay in constructing the tower and the lack of proper quality were one of the main reasons for the failure of the project”.

In October 2012, when the supplier commenced installation, the work was soon abandoned after the vehicle carrying the heavy crane required to lift the radar equipment crashed down the mountain. The next attempt was made in October 2013, one year later. Although the equipment was installed, the system could not be operationalised because electronic connectivity was not provided (as stated in the audit report).

In 2015, following a UNOPS (United Nations Office for Project Services) inspection, it was determined that the equipment needed to be returned to the supplier because some sensitive electronic devices had been damaged due to long-term disuse, and a further 1.5 years had elapsed by 2017, when the equipment was finally returned to the supplier. In March 2018, the estimated repair cost was USD 1,095,935, which was deemed excessive, and the project was abandoned.

COPA proceedings

The Committee on Public Accounts (COPA) discussed the radar project on August 10, 2023, and several press reports state that the GOSL incurred a loss of Rs. 78 million due to the project’s failure. This, I believe, is the cost of constructing the Tower. It is mentioned that Rs. 402 million had been spent on the radar system, of which Rs. 323 million was drawn from the trust fund established with WMO. It was also highlighted that approximately Rs. 8 million worth of equipment had been stolen and that the Police and the Bribery and Corruption Commission were investigating the matter.

JICA support and project stagnation

Despite the project’s failure with WMO, the Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA) entered into an agreement with GOSL on June 30, 2017 to install two Doppler Radar Systems in Puttalam and Pottuvil. JICA has pledged 2.5 billion Japanese yen (LKR 3.4 billion at the time) as a grant. It was envisaged that the project would be completed in 2021.

Once again, the perennial delays that afflict the GOSL and bureaucracy have resulted in the groundbreaking ceremony being held only in December 2024. The delay is attributed to the COVID-19 pandemic and Sri Lanka’s economic crisis.

The seven-year delay between the signing of the agreement and project commencement has led to significant cost increases, forcing JICA to limit the project to installing only one Doppler Radar system in Puttalam.

Impact of the missing radar during Ditwah

As I am not a meteorologist and do not wish to make a judgment on this, I have decided to include the statement issued by JICA after the groundbreaking ceremony on December 24, 2024.

“In partnership with the Department of Meteorology (DoM), JICA is spearheading the establishment of the Doppler Weather Radar Network in the Puttalam district, which can realize accurate weather observation and weather prediction based on the collected data by the radar. This initiative is a significant step in strengthening Sri Lanka’s improving its climate resilience including not only reducing risks of floods, landslides, and drought but also agriculture and fishery“.

Based on online research, a Doppler Weather Radar system is designed to observe weather systems in real time. While the technical details are complex, the system essentially provides localized, uptotheminute information on rainfall patterns, storm movements, and approaching severe weather. Countries worldwide rely on such systems to issue timely alerts for monsoons, tropical depressions, and cyclones. It is reported that India has invested in 30 Doppler radar systems, which have helped minimize the loss of life.

Without radar, Sri Lanka must rely primarily on satellite imagery and foreign meteorological centres, which cannot capture the finescale, rapidly changing weather patterns that often cause localized disasters here.

The general consensus is that, while no single system can prevent natural disasters, an operational Doppler Radar almost certainly would have strengthened Sri Lanka’s preparedness and reduced the extent of damage and loss.

Conclusion

Sri Lanka’s inability to commission a Doppler Radar system, despite nearly two decades of attempts, represents one of the most significant governance failures in the country’s disastermanagement history.

Audit findings, parliamentary oversight proceedings, and donor records all confirm the same troubling truth: Sri Lanka has spent public money, signed international agreements, received foreign assistance, and still has no operational radar. This raises a critical question: should those responsible for this prolonged failure be held legally accountable?

Now may not be the time to determine the extent to which the current government and bureaucrats failed the people. I believe an independent commission comprising foreign experts in disaster management from India and Japan should be appointed, maybe in six months, to identify failures in managing Cyclone Ditwah.

However, those who governed the country from 2007 to 2024 should be held accountable for their failures, and legal action should be pursued against the politicians and bureaucrats responsible for disaster management for their failure to implement the 2007 project with the WMO successfully.

Sri Lanka cannot afford another 18 years of delay. The time for action, transparency, and responsibility has arrived.

(The views and opinions expressed in this article are solely those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the policy or position of any organization or institution with which the author is affiliated).

By Sanjeewa Jayaweera

Features

Ramifications of Trump Corollary

President Trump is expected to close the deal on the Ukraine crisis, as he may wish to concentrate his full strength on two issues: ongoing operations in Venezuela and the bolstering of Japan’s military capabilities as tensions between China and Japan over Taiwan rise. Trump can easily concede Ukraine to Putin and refocus on the Asia–Pacific and Latin America. This week, he once again spilled the beans in an interview with Politico, one of the most significant conversations ever conducted with him. When asked which country currently holds the stronger negotiating position, Trump bluntly asserted that there could be no question: it is Russia. “It’s a much bigger country. It’s a war that should’ve never happened,” he said, followed by his usual rhetoric.

Meanwhile, US allies that fail to adequately fund defence and shirk contributions to collective security will face repercussions, Secretary of War Pete Hegseth declared at the 2025 Reagan National Defense Forum in Simi Valley, California. Hegseth singled out nations such as South Korea, Israel, Poland, and Germany as “model allies” for increasing their commitments, contrasting them with those perceived as “free riders”. The message was unmistakably Trumpian: partnerships are conditional, favourable only to countries that “help themselves” before asking anything of Washington.

It is in this context that it becomes essential to examine the Trump administration’s National Security Strategy, issued last week, in order to consider how it differs from previous strategies and where it may intersect with current US military practice.

Trump’s 2025 National Security Strategy is not merely another iteration of the familiar doctrine of American primacy; it is a radical reorientation of how the United States understands itself, its sphere of influence, and its role in the world. The document begins uncompromisingly: “The purpose of foreign policy is the protection of core national interests; that is the sole focus of this strategy.” It is the bluntest opening in any American NSS since the document became a formal requirement in 1987. Whereas previous strategies—from Obama to Biden—wrapped security in the language of democracy promotion and multilateralism, Trump’s dispenses entirely with the pretence of universality. What matters are American interests, defined narrowly, almost corporately, as though the United States were a shareholder entity rather than a global hegemon.

It is here that the ghost of Senator William Fulbright quietly enters, warning in 1966 that “The arrogance of power… the belief that we are uniquely qualified to bring order to the world, is a dangerous illusion.” Fulbright’s admonition was directed at the hubris of Vietnam-era expansionism, yet it resonates with uncanny force in relation to Trump’s revived hemispheric ambitions. For despite Trump’s anti-globalist posture, his strategy asserts a unique American role in determining events across two oceans and within an entire hemisphere. The arrogance may simply be wearing a new mask.

Nowhere is this revisionist spirit more vivid than in the so-called “Trump Corollary to the Monroe Doctrine”, perhaps the most controversial American hemispheric declaration since Theodore Roosevelt’s time. The 2025 NSS states without hesitation that “The United States will reassert and enforce the Monroe Doctrine to restore American preeminence in the Western Hemisphere.” Yet unlike Roosevelt, who justified intervention as a form of pre-emptive stabilisation, Trump wraps his corollary in the language of sovereignty and anti-globalism. The hemispheric message is not simply that outside powers must stay out; it is that the United States will decide what constitutes legitimate governance in the region and deny “non-Hemispheric competitors the ability to position forces or other threatening capabilities… in our Hemisphere”.

This wording alone has far-reaching implications for Venezuela, where US forces recently seized a sanctioned supertanker as part of an escalating confrontation with the Maduro government. Maduro, emboldened by support from Russia, Iran, and China’s so-called shadow fleet, frames Trump’s enforcement actions as piracy. But for Trump, this is precisely the point: a demonstration of restored hemispheric authority. In that sense, the 2025 NSS may be the first strategic document in decades to explicitly set the stage for sustained coercive operations in Latin America. The NSS promises “a readjustment of our global military presence to address urgent threats in our Hemisphere.” “Urgent threats” is vague, but in practical military planning, vagueness functions as a permission slip. It is not difficult to see how a state accused of “narco-terrorism” or “crimes against humanity” could be fitted into the category.

The return to hemispheric dominance is paired with a targeted shift in alliance politics. Trump makes it clear that the United States is finished subsidising alliances that do not directly strengthen American security. The NSS lays out the philosophy succinctly: “The days of the United States propping up the entire world order like Atlas are over.” This is a direct repudiation of the language found in Obama’s 2015 NSS, which emphasised that American leadership was indispensable to global stability. Trump rejects that premise outright. Leadership, in his framing, is merely leverage. Allies who fail to meet burden expectations will lose access, influence, and potentially even protection. Nowhere is this more evident than in the push for extraordinary defence spending among NATO allies: “President Trump has set a new global standard with the Hague Commitment… pledging NATO countries to spend 5 percent of GDP on defence.”

In turn, US disengagement from Europe becomes easier to justify. While Trump speaks of “negotiating an expeditious cessation of hostilities in Ukraine”, it requires little sophistication to decode this as a form of managed abandonment—an informal concession that Russia’s negotiating position is stronger, as Trump told Politico. Ukraine may well become a bargaining chip in the trade-off between strategic theatres: Europe shrinks, Asia and Latin America expand. The NSS’s emphasis on Japan, Taiwan, and China is markedly sharper than in 2017.

China looms over the 2025 NSS like an obsession, mentioned over twenty times, not merely as a competitor but as a driving force shaping American policy. Every discussion of technology, alliances, or regional security is filtered through Beijing’s shadow, as if US strategy exists solely to counter China. The strategy’s relentless focus risks turning global priorities into a theatre of paranoia, where the United States reacts constantly, defined less by its own interests than by fear of what China might do next.

It is equally striking that, just nine days after Cyclone Ditwah, the US Indo-Pacific Command deployed two C130 aircraft—capable of landing at only three locations in Sri Lanka, well away from the hardest-hit areas—and orchestrated a highly choreographed media performance, enlisting local outlets and social media influencers seemingly more concerned with flaunting American boots on the ground than delivering “urgent” humanitarian aid. History shows this is not unprecedented: US forces have repeatedly arrived under the banner of humanitarian assistance—Operation Restore Hope in Somalia (1992) later escalated into full security and combat operations; interventions in Haiti during the 1990s extended into long-term peacekeeping and training missions; and Operation United Assistance in Liberia (2014) built a lasting US operational presence beyond the Ebola response.

Trump’s NSS, meanwhile, states that deterring conflict in East Asia is a “priority”, and that the United States seeks to ensure that “US technology and US standards—particularly in AI, biotech, and quantum computing—drive the world forward.” Combined with heightened expectations of Japan, which is rapidly rearming, Trump’s strategic map shows a clear preference: if Europe cannot or will not defend itself, Asia might.

What makes the 2025 NSS uniquely combustible, however, is the combination of ideological framing and operational signalling. Trump explicitly links non-interventionism, long a theme of his political base, to the Founders’ moral worldview. He writes that “Rigid adherence to non-interventionism is not possible… yet this predisposition should set a high bar for what constitutes a justified intervention.”

The Trump NSS is both a blueprint and a warning. It signals a United States abandoning the liberal internationalist project and embracing a transactional, hemispherically focussed, sovereignty-first model. It rewrites the Monroe Doctrine for an age of great-power contest, but in doing so resurrects the very logics of intervention that past presidents have regretted. And in the background, as Trump weighs the cost of Ukraine against the allure of a decisive posture in Asia and the Western Hemisphere, the world is left to wonder whether this new corollary is merely rhetorical theatre or the prelude to a new era of American coercive power. The ambiguity is deliberate, but the direction of travel is unmistakable.

[Correction: In my column last week, I incorrectly stated that India–Russia trade in FY 2024 25 was USD 18 billion; the correct figure is USD 68.7 billion, with a trade deficit of about USD 59 billion. Similarly, India recorded a goods trade surplus of around USD 41.18 billion with the US, not a deficit of USD 42 billion, with exports of USD 86.51 billion and imports of USD 45.33 billion. Total remittances to India in FY 2024 25 were roughly USD 135.46 billion, including USD 25–30 billion from the US. Apologies for the error.]

by Nilantha Ilangamuwa

Features

MEEZAN HADJIAR

selfmade businessman who became one of the richest men in the Central Province

I am happy that a book about the life and contribution of Sathkorale Muhamdiramlagedara Segu Abdul Cader Hajiar Mohamed Mohideen better known as Meezan Hadjiar or Meezan Mudalali of Matale [1911—1964] written by Mohammed Fuaji -a former Principal of Zahira College Matale, has now been published by a group of his admirers and relatives. It is a timely addition to the history of Matale district and the Kandyan region which is yet to be described fully as forming a part of the modern history of our country. Coincidentally this book also marks the centenary of Meezan Hadjiars beginning of employment in Matale town which began in 1925.

Matale which was an outlier in the Kandyan Kingdom came into prominence with the growth of plantations for coffee and, after the collapse of the coffee plantations due to the ‘coffee blight’ , for other tree crops . Coffee was followed by the introduction of tea by the early British investors who faced bankruptcy and ruin if they could not quickly find a substitute beverage for coffee.They turned to tea.

The rapid opening of tea plantations in the hill country demanded a large and hardworking labour force which could not be found domestically. This led to the indenturing of Tamil labour from South India on a large scale. These helpless workers were virtually kidnapped from their native villages in India through the Kangani system and they were compelled to migrate to our hill country by the British administration .

The route of these indentured workers to the higher elevations of the hill country lay through Matale and the new plantation industry developed in that region thereby dragging it into a new commercial culture and a cash economy. New opportunities were opened up for internal migration particularly for the more adventurous members of the Muslim community who had played a significant role in the Kandyan kingdom particularly as traders,transporters,medical specialists and military advisors.

Diaries of British officials like John D’oyly also show that the Kandyan Muslims were interlocutors between the Kandyan King and British officials of the Low Country as they had to move about across boundaries as traders of scarce commodities like salt, medicines and consumer articles for the Kandyans and arecanuts, gems and spices for the British. Even today there are physical traces of the ‘’Battal’’or caravans of oxen which were used by the Muslims to transport the above mentioned commodities to and from the Kandyan villages to the Low country. Another important facet was that Kandyan Muslims were located in villages close to the entrances to the hill country attesting to their mobility unlike the Kandyan villagers.

Thus Akurana, Galagedera, Kadugannawa, Hataraliyadde and Mawanella which lay in the pathways to enter the inner territory of the Kings domain were populated by ‘Kandyan Muslims’ who had the ear of the King and his high officials. The’’ Ge’’ names and the honorifics given by the King were a testament to their integration with the Sinhala polity. Meezan Hadjiars’’ Ge ‘‘name of Sathkorale Mohandiramlage denotes the mobility of the family from Sathkorale, an outlier division in the Kandyan Kingdom, and Mohandiramlage attests to the higher status in the social hierarchy which probably indicated that his forebears were honoured servants of the king.

Meezan Hadjiar [SM Mohideen] was born and bred in Kurugoda which is a small village in Akurana in Kandy district. He belonged to the family of Abdul Cader who was a patriarch and a well known religious scholar. Cader’s children began their education in the village school but at the age of 12 young Mohideen left his native village to apprentice under a relative who had a business establishment in the heart of Matale town which was growing fast due to the economic boom. It must be stated here that this form of ‘learning the ropes’ as an apprentice’was a common path to business undertaken by many of the later Sri Lankan tycoons of the pre-independence era.

But he did not remain in that position for long .When his mentor failed in his business of trading in cocoa, cardamoms, cloves and arecanuts and wanted to close up his shop young Mohideen took over and eventually made a great success of it. His enterprise succeeded because he was able to earn the trust of both his buyers and sellers. He befriended Sinhalese and Tamil producers and the business he improved beyond measure took on the name of Meezan Estates Ltd [The scales] and Mohideen soon became famous as Meezan Mudalali – perhaps the most successful businessman of his time in Matale. He expanded his business interests to urban real estate as well as tea and rubber estates. Soon he owned over 3,000 acres of tea estates making him one of the richest men in the Central Province.

With his growing influence Meezan spent generously on charitable activities including funding a water scheme for his native village of Kurugoda also serving adjoining villages like Pangollamada located in Akurana. He also gave generously to Buddhist causes in Matale together with other emerging low country businessmen like Gunasena and John Mudalali.

Matale was well known as a town in which all communities lived in harmony and tended to help each other. As a generous public figure he became strong supporter of the UNP and a personal friend of its leaders like Dudley Senanayake and Sir John Kotelawela. UNP candidates for public office-both in the Municipality and Parliament were selected in consultation with Meezan who also bankrolled them during election time. He himself became a Municipal councillor. The Aluvihares of several generations had close links with him. it was Meezan who mentored ACS Hameed – a fellow villager from Kurugoda – and took him to the highest echelons of Sri Lankan politics as Minister of Foreign Affairs. He was a supporter and financier of the UNP through thick and thin.

Though his premature death at the age 53 in 1965 saved him from the worst political witch hunts under SWRD Bandaranaike who was his personal friend it was after 1970 and the Coalition regime that Meezan’s large family were deprived of their livelihood by the taking over of all their estates. Fortunately many of his children were well educated and could hold on till relief was given by President Premadasa despite the objections of their father’s erstwhile protégé ACS Hameed who surprisingly let them down badly.

It is only fitting that we, even a hundred years later, now commemorate a great self made Sri Lankan business magnate and generous contributor to all religious and social causes of his time. His name became synonymous with enterprise in Matale – a district in which I was privileged to serve as Government Agent in the late sixties.He was a model entrepreneur and his large family have also made outstanding contributions to this country which also attest to the late Meezan Hadjiars foresight and vision of a united and prosperous Srilanka.

by SARATH AMUNUGAMA.

-

Features5 days ago

Features5 days agoFinally, Mahinda Yapa sets the record straight

-

News7 days ago

News7 days agoOver 35,000 drug offenders nabbed in 36 days

-

News6 days ago

News6 days agoCyclone Ditwah leaves Sri Lanka’s biodiversity in ruins: Top scientist warns of unseen ecological disaster

-

News7 days ago

News7 days agoRising water level in Malwathu Oya triggers alert in Thanthirimale

-

Features5 days ago

Features5 days agoHandunnetti and Colonial Shackles of English in Sri Lanka

-

Business4 days ago

Business4 days agoCabinet approves establishment of two 50 MW wind power stations in Mullikulum, Mannar region

-

Business7 days ago

Business7 days agoSri Lanka betting its tourism future on cold, hard numbers

-

News7 days ago

News7 days agoJetstar to launch Australia’s only low-cost direct flights to Sri Lanka, with fares from just $315^