Features

Charting a new history, for a new future

By Uditha Devapriya

For Sinhala nationalists, I daresay the history of Sri Lanka remains the history of the Sinhala people. This begs two questions: one, who are these Sinhala people, and two, where does their history begin? The typical nationalist response to these would be, first, that Sinhala people are those who form the majority in the country, and second that their history begins with the advent of kinship as outlined in chronicles like the Mahavamsa.

But such responses ignore important historical considerations, like the fact that the kings of Sri Lanka, or at least the first among them, hailed from India, or that the chronicles refer to a civilisation that is supposed to have predated their arrival.

How do nationalists resolve these contradictions? They would probably contend that the island possessed a civilisation that was eminently different and superior to that which kings brought about here, while conceding that the latter also developed the country. After all, there are important debates over historiography within nationalist circles, boiling down to whether we to trace our ancestry back by 2,500 years, to the colonisation of the country by Indo-Aryan tribes, or by 10,000 years, to the formation of a pre-Indian, pre-Aryan civilisation supposedly free of external influences. Though there’s no real archaeological evidence for the latter view, there is no shortage of popular writers who speculate about Sinhala people being bearers of a culture predating the Indian influence.

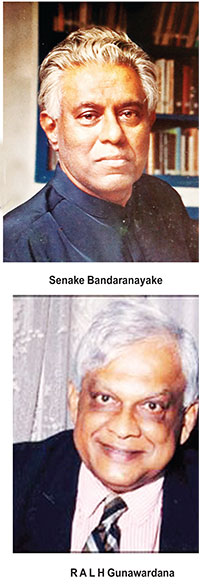

It must be pointed out that the notion of race figures prominently in both cases. In fact, for Sinhala nationalists as much as for Tamil, Muslim, and other nationalists, race remains the primary consideration, the only priority. It is true that as R. A. L. H. Gunawardana has noted that in European languages the word race “dates only from about the sixteenth century”, while neither Sinhala nor Tamil has a satisfactory equivalent for it. Yet for nationalists, history is at best a series of encounters between ethnic groups. Thus, whether they are talking about a prodigal son from northern India conquering the island of Tampabanni or a ten-headed king ruling the island long before the arrival of that son, they reduce the history of the country to the history of a dominant group. This is essentialist scholarship at its crudest.

Nationalists, of course, can be flexible on these matters. They often are. For instance, one prominent Jathika Chintanaya intellectual claimed, at a public seminar, that the Nayakkar kings of Kandy could become Sinhalese after they had been absorbed to the Sinhala social structure in the same way that Victoria, despite not being proficient in English, could turn into an English queen. But on the same grounds, these intellectuals and commentators talk of terms like Sinhalathvaya as if they are etched in stone. While they would readily accept that the Nayakkars became Sinhala because they were kings and had to be benefactors or be seen as benefactors of Buddhism, they would deny that Muslims could be absorbed into Sinhala social structures or take part in Sinhala rituals. According to their logic, to “become” Sinhala is a preserve of a ruling class that cannot be allowed for other groups.

The case of Wath Himi Kumaraya, popularly known as Gale Bandara Deviyo, shows how this kind of essentialism can blind us to the intricacies of our history. While records are unclear about his origins, what we can gather from them is the account of a Muslim pretender to the throne being killed by a group of nobles, only to be venerated later by adherents of both Islam and Buddhism. The transformation of a Muslim usurper to a popular deity is of course a fascinating historical anomaly in a thoroughly Sinhala and Buddhist realm, but one which seems to be appreciated by few, if at all. Certainly, a racialist historiography would ignore or omit such details, while those who subscribe to such histories would be ignorant of them: I myself realised this the other day when, after I suggested that Gale Bandara was “Muslim”, a lad of 19 argued passionately that Buddhists should stop venerating him!

The case of Wath Himi Kumaraya, popularly known as Gale Bandara Deviyo, shows how this kind of essentialism can blind us to the intricacies of our history. While records are unclear about his origins, what we can gather from them is the account of a Muslim pretender to the throne being killed by a group of nobles, only to be venerated later by adherents of both Islam and Buddhism. The transformation of a Muslim usurper to a popular deity is of course a fascinating historical anomaly in a thoroughly Sinhala and Buddhist realm, but one which seems to be appreciated by few, if at all. Certainly, a racialist historiography would ignore or omit such details, while those who subscribe to such histories would be ignorant of them: I myself realised this the other day when, after I suggested that Gale Bandara was “Muslim”, a lad of 19 argued passionately that Buddhists should stop venerating him!

I am not certain to what extent local textbooks reinforce racialist accounts of local history. I am certain, though, that these texts do not inculcate in their readers an appreciation of the many groups that form the identity of the country. Paradoxically, while reinforcing ethnic or religious supremacy, textbook accounts borrow concepts steeped in Western ideology. The notion of race is just one example, as is the origin of terms like Aryan, which had to do with the identity of a ruling class rather than of a hegemonic ethnic community.

This is a paradox that writers who privilege the racialist dimensions of history are not bothered with: even in their rejection of “Western” notions of multiethnic identity, they subscribe to other dominant “Western” notions, which happen to be as pervasive, if not more so. How can we address such contradictions? How can we resolve them? A good first step would be to historicise and find out what can be done with them.

By the early 20th century, debates and polemics had begun to crop up over issues of racial identity, territorial rights, ethnic distinctions, and so on, a point Senake Bandaranayake has made in his essay on “The Peopling of Sri Lanka.” Those who took part in these discussions fell back on divisions that European philologists and orientalists had drawn, between ethnic groups, on the basis of certain characteristics such as dialect and dress type.

What these examinations left out, which scientific advancements have made it possible for us to ascertain today, were the commonalities that link communities together. As evident and common as certain biological traits may be within communities, these by themselves, as Bandaranayake and Gunawardana have noted, by no means warrant the use of categories like race, which are so fluid they can’t be used as markers of distinction.

Perhaps what lent credence to such essentialist views was the scheme that early historians adopted in their periodisations of local history. As in India, where colonial scholars made an arbitrary and imaginary distinction between classical Hindu and decadent Muslim phases, in Sri Lanka they drew lines between a pristine medieval culture and a decadent pre-colonial phase, the latter usually identified with the period of the Kandyan kings. Other scholars took a further step by identifying not the Kandyan kingdom but colonial rule as decadent, in stark contrast to the Anuradhapura and Polonnaruwa periods.

Whatever the biases of the scholar would have been, the drawing up of chronological divisions along these lines made it possible for popular writers to fit their racialist accounts of history within such schemes later on, though history, as Senake Bandaranayake and R. A. L. H. Gunawardana have shown, rebels against such chronologies.

The biggest omission made by those who saw history as a contest between ethnicities was the issue of caste, which remains the least understood social phenomenon in Sri Lanka. The stalwarts of the Marxist Left, including Hector Abhayavardhana, forayed into rural society at the height of the Suriya Mal and anti-malaria campaigns of the 1930s, making it possible for scholars to examine social stratifications from a materialist perspective. Yet, over the years, discussions of such stratifications have tended to wane.

To me this is a striking omission. Intra-group differences are as important as inter-group ones. They emphasise the rifts that exist, not only at the racial level between communities, but also at caste and class levels, within the same communities.

For the most, sadly, historians and writers, be they “Marxist”, liberal, or nationalist, have ignored these considerations. That has led to a situation where, while rejecting the racialist rhetoric of nationalists, liberal scholars have fallen back on criteria no different from those which nationalist ideologues adopt. Hence, accounts of Moor, Malay, Tamil, even Burgher contributions to Sri Lankan society valorise these communities in an ethnic light, portraying them as racial types against which nationalists bring up their claims of superiority. Whether or not they intend it, then, the most progressive of Sri Lankan scholars provide ammunition for nationalist debates, given that they also view history through an ethnic lens. Perhaps the best example for this would be the notion of “Tamil Buddhism” in Sri Lanka, raised by social scientists, and the knee-jerk rejection of such a thesis by Sinhala nationalists.

I believe the first step towards liberating Sri Lankan historiography from its fixation with ethnicity and racialism would be, as Senake Bandaranayake noted, to consider the history of ethnic formation in the country as a complex process involving “the convergence of various pre and proto-historic developments.” On the one hand, nationalist historians are adamant on constructing a Sinhala Buddhist identity. On the other, the liberals’ response frames the issue in racial terms and adopts the criteria used by their opponents, hence legitimising the latter. Both approaches lead to a dead-end, and so both should be discarded.

The solution, perfectly sensible in my view, would be to start examining history from the vantage point of other social phenomena, like caste. In doing so, we will be able to come up with a historiography which places emphasis on the differences separating groups as much as on the commonalities binding them. To quote Senake Bandaranayake here, “[a] study of Sri Lankan history, stripped of its myths and distortions and free of communalist bias on one side or the other, can do much to contribute to the historic process of the formation of an integrated polyethnic modern nation.” We obviously have a long way to go.

The writer can be reached at udakdev1@gmail.com

Features

Voting for new Pope set to begin with cardinals entering secret conclave

On Wednesday evening, under the domed ceiling of Michelangelo’s Sistine Chapel, 133 cardinals will vote to elect the Catholic Church’s 267th pope.

The day will begin at 10:00 (09:00 BST) with a mass in St Peter’s Basilica. The service, which will be televised, will be presided over by Giovanni Battista Re, the 91-year-old Cardinal Dean who was also the celebrant of Pope Francis’ funeral.

In the early afternoon, mobile signal within the territory of the Vatican will be deactivated to prevent anyone taking part in the conclave from contacting the outside world.

Around 16:15 (15:15 BST), the 133 cardinal electors will gather in the Pauline Chapel and form a procession to the Sistine Chapel.

Once in the Sistine Chapel, one hand resting on a copy of the Gospel, the cardinals will pronounce the prescribed oath of secrecy which precludes them from ever sharing details about how the new Pope was elected.

When the last of the electors has taken the oath, a meditation will be held. Then, the Master of Pontifical Liturgical Celebrations Diego Ravelli will announce “extra omnes” (“everybody out”).

He is one of three ecclesiastical staff allowed to stay in the Sistine Chapel despite not being a cardinal elector, even though they will have to leave the premises during the counting of the votes.

The moment “extra omnes” is pronounced marks the start of the cardinals’ isolation – and the start of the conclave.

The word, which comes from the Latin for “cum clave”, or “locked with key” is slightly misleading, as the cardinals are no longer locked inside; rather, on Tuesday Vatican officials closed the entrances to the Apostolic Palace – which includes the Sistine Chapel- with lead seals which will remain until the end of the proceedings. Swiss guards will also flank all the entrances to the chapel.

Diego Ravelli will distribute ballot papers, and the cardinals will proceed to the first vote soon after.

While nothing forbids the Pope from being elected with the first vote, it has not happened in centuries. Still, that first ballot is very important, says Austen Ivereigh, a Catholic writer and commentator.

“The cardinals who have more than 20 votes will be taken into consideration. In the first ballot the votes will be very scattered and the electors know they have to concentrate on the ones that have numbers,” says Ivereigh.

He adds that every other ballot thereafter will indicate which of the cardinals have the momentum. “It’s almost like a political campaign… but it’s not really a competition; it’s an effort by the body to find consensus.”

If the vote doesn’t yield the two-third majority needed to elect the new pope, the cardinals go back to guesthouse Casa Santa Marta for dinner. It is then, on the sidelines of the voting process, that important conversations among the cardinals take place and consensus begins to coalesce around different names.

According to Italian media, the menu options consist of light dishes which are usually served to guests of the residence, and includes wine – but no spirits. The waiters and kitchen staff are also sworn to secrecy and cannot leave the grounds for the duration of the conclave.

From Thursday morning, cardinals will be taking breakfast between 06:30 (05:30 BST) and 07:30 (06:30 BST) ahead of mass at 08:15 (07:15 BST). Two votes then take place in the morning, followed by lunch and rest. In his memoirs, Pope Francis said that was when he began to receive signals from the other cardinals that serious consensus was beginning to form around him; he was elected during the first afternoon vote. The last two conclaves have all concluded by the end of the second day.

There is no way of knowing at this stage whether this will be a long or a short conclave – but cardinals are aware that dragging the proceedings on could be interpreted as a sign of gaping disagreements.

As they discuss, pray and vote, outside the boarded-up windows of the Sistine Chapel thousands of faithful will be looking up to the chimney to the right of St Peter’s Basilica, waiting for the white plume of smoke to signal that the next pope has been elected.

[BBC]

Features

Beyond Left and Right: From Populism to Pragmatism and Recalibrating Democracy

The world is going through a political shake-up. Everywhere you look—from Western democracies to South Asian nations—people are choosing leaders and parties that seem to clash in ideology. One moment, a country swings left, voting for progressive policies and climate action. The next, a neighbouring country rushes into the arms of right-wing populism, talking about nationalism and tradition.

It’s not just puzzling—it’s historic. This global tug of war between opposing political ideas is unlike anything we’ve seen in recent decades. In this piece, I explore this wave of political contradictions, from the rise of labour movements in Australia and Canada, to the continued strength of conservative politics in the US and India, and finally to the surprising emergence of a radical leftist party in Sri Lanka.

Australia and Canada: A Comeback for Progressive Politics

Australia recently voted in the Labour Party, with Anthony Albanese becoming Prime Minister after years of conservative rule under Scott Morrison. Albanese brought with him promises of fairer wages, better healthcare, real action on climate change, and closing the inequality gap. For many Australians, it was a fresh start—a turn away from business-as usual politics.

In Canada, a political shift is unfolding with the rise of The Right Honourable Mark Carney, who became Prime Minister in March 2025, after leading the Liberal Party. Meanwhile, Jagmeet Singh and the New Democratic Party (NDP) are gaining traction with their progressive agenda, advocating for enhanced social safety nets in healthcare and housing to address growing frustrations with rising living costs and a strained healthcare system..

But let’s be clear—this isn’t a return to old-school socialism. Instead, voters seem to be leaning toward practical, social-democratic ideas—ones that offer government support without fully rejecting capitalism. People are simply fed up with policies that favour the rich while ignoring the struggles of everyday families. They’re calling for fairness, not radicalism.

America’s Rightward Drift: The Trump Effect Still Lingers

In contrast, the political story in the United States tells a very different tale. Even after Donald Trump left office in 2020, the Republican Party remains incredibly powerful—and popular.

Trump didn’t win hearts through traditional conservative ideas. Instead, he tapped into a raw frustration brewing among working-class Americans. He spoke about lost factory jobs, unfair trade deals, and an elite political class that seemed disconnected from ordinary life. His messages about “America First” and restoring national pride struck a chord—especially in regions hit hard by globalisation and automation.

Despite scandals and strong opposition, Trump’s brand of politics—nationalist, anti-immigration, and skeptical of global cooperation—continues to dominate the Republican Party. In fact, many voters still see him as someone who “tells it like it is,” even if they don’t agree with everything he says.

It’s a sign of a deeper trend: In the US, cultural identity and economic insecurity have merged, creating a political environment where conservative populism feels like the only answer to many.

India’s Strongman Politics: The Modi Era Continues

Half a world away, India is witnessing its own version of populism under Prime Minister Narendra Modi. His party—the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP)—has ruled with a blend of Hindu nationalism, economic ambition, and strong leadership.

Modi is incredibly popular. His supporters praise his development projects, digital push, and efforts to raise India’s profile on the global stage. But critics argue that his leadership is dividing the country along religious lines and weakening its long-standing secular values.

Still, for many Indians—especially the younger generation and the rural poor—Modi represents hope, strength, and pride. They see him as someone who has delivered where previous leaders failed. Whether it’s building roads, providing gas connections to villages, or cleaning up bureaucracy, the BJP’s strong-arm tactics have resonated with large sections of the population.

India’s political direction shows how nationalism can be powerful—especially when combined with promises of economic progress and security.

A Marxist Comeback? Sri Lanka’s Political Wild Card

Then there’s Sri Lanka—a country in crisis, where politics have taken a shocking turn.

For decades, Sri Lanka was governed by familiar faces and powerful families. But after years of financial mismanagement, corruption, and a devastating economic collapse, public trust in mainstream parties has plummeted. Into this void stepped a party many thought had been sidelined for good—the Janatha Vimukthi Peramuna (JVP), a Marxist-Leninist group with a history of revolutionary roots.

Once seen as radical and even dangerous, the JVP has rebranded itself as a disciplined, modern political force. Today, it speaks directly to the country’s suffering masses: those without jobs, struggling to buy food, and fed up with elite corruption.

The party talks about fair wealth distribution, workers’ rights, and standing up to foreign economic pressures. While their ideas are left-leaning, their growing support is driven more by public frustration with current political leaders than by any shift toward Marxism by the public or any move away from it by the JVP.

Sri Lanka’s case is unique—but not isolated. Across the world, when economies collapse and inequality soars, people often turn to ideologies that offer hope and accountability—even if they once seemed extreme.

A Global Puzzle: Why Are Politics So Contradictory Now?

So what’s really going on? Why are some countries swinging left while others turn right?

The answer lies in the global crises and rapid changes of the past two decades. The 2008 financial crash, worsening inequality, mass migrations, terrorism fears, the COVID-19 pandemic, and now climate change have all shaken public trust in traditional politics.

Voters everywhere are asking the same questions: Who will protect my job? Who will fix healthcare? Who will keep us safe? The answers they choose depend not just on ideology, but on their unique national experiences and frustrations.

In countries where people feel abandoned by global capitalism, they may choose left-leaning parties that promise welfare and fairness. In others, where cultural values or national identity feel under threat, right-wing populism becomes the answer.

And then there’s the digital revolution. Social media has turbocharged political messaging. Platforms like Twitter, Facebook, and YouTube allow both left and right movements to reach people directly—bypassing traditional media. While this has given power to progressive youth movements, it’s also allowed misinformation and extremist views to flourish, deepening polarisation.

Singapore: The Legacy of Pragmatic Leadership and Technocratic Governance

Singapore stands as a unique case in the global political landscape, embodying a model of governance that blends authoritarian efficiency with capitalist pragmatism. The country’s political identity has been shaped largely by its founding Prime Minister, Lee Kuan Yew, often regarded as a political legend for transforming a resource-poor island into one of the most prosperous and stable nations in the world. His brand of leadership—marked by a strong central government, zero tolerance for corruption, and a focus on meritocracy—has continued to influence Singapore’s political ideology even after his passing. The ruling People’s Action Party (PAP), which has been in power since independence, remains dominant, but it has had to adapt to a new generation of voters demanding more openness, transparency, and participatory governance.

Despite criticisms of limited political pluralism, Singapore’s model is often admired for its long-term planning, public sector efficiency, and ability to balance rapid economic development with social harmony. In an era of rising populism and political fragmentation elsewhere, Singapore’s consistent technocratic approach provides a compelling counter-narrative—one that prioritises stability, strategic foresight, and national cohesion over ideological extremes.

What the Future Holds

We are living in a time where political boundaries are blurring, and old labels don’t always fit. Left and right are no longer clear-cut. Populists can be socialist or ultra-conservative. Liberals may support strong borders. Conservatives may promote welfare if it wins votes.

What matters now is trust—people are voting for those who seem to understand their pain, not just those with polished manifestos.

As economic instability continues and global challenges multiply, this ideological tug-of-war is likely to intensify. Whether we see more progressive reforms or stronger nationalist movements will depend on how well political leaders can address real issues, from food security to climate disasters.

One thing is clear: the global political wave is still rising. And it’s carrying countries in very different directions.

Conclusion

The current wave of global political ideology is defined by its contradictions, complexity, and context-specific transformations. While some nations are experiencing a resurgence of progressive, left-leaning movements—such as Australia’s Labour Party, Canada’s New Democratic Party, and Sri Lanka’s Marxist-rooted JVP—others are gravitating toward right-wing populism, nationalist narratives, and conservative ideologies, as seen in the continued strength of the US Republican Party and the dominant rule of Narendra Modi’s BJP in India. Amid this ideological tug-of-war, Singapore presents a unique political model. Eschewing populist swings, it has adhered to a technocratic, pragmatic form of governance rooted in the legacy of Lee Kuan Yew, whose leadership transformed a struggling post-colonial state into a globally admired economic powerhouse. Singapore’s emphasis on strategic planning, meritocracy, and incorruptibility provides a compelling contrast to the ideological turbulence in many democracies.

What ties these divergent trends together is a common undercurrent of discontent with traditional politics, growing inequality, and the digital revolution’s impact on public discourse. Voters across the world are searching for leaders and ideologies that promise clarity, security, and opportunity amid uncertainty. In mature democracies, this search has split into dual pathways—either toward progressive reform or nostalgic nationalism. In emerging economies, political shifts are even more fluid, influenced by economic distress, youth activism, and demands for institutional change.

Ultimately, the world is witnessing not a single ideological revolution, but a series of parallel recalibrations. These shifts do not point to the triumph of one ideology over another, but rather to the growing necessity for adaptive, responsive, and inclusive governance. Whether through leftist reforms, right-wing populism, or technocratic stability like Singapore’s, political systems will increasingly be judged not by their ideological purity but by their ability to address real-world challenges, unite diverse populations, and deliver tangible outcomes for citizens. In that respect, the global political wave is not simply a matter of left vs. right—it is a test of resilience, innovation, and leadership in a rapidly evolving world.

(The writer, a senior Chartered Accountant and professional banker, is Professor at SLIIT , Malabe. He is also the author of the “Doing Social Research and Publishing Results”, a Springer publication (Singapore), and “Samaja Gaveshakaya (in Sinhala). The views and opinions expressed in this article are solely those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the institution he works for. He can be contacted at saliya.a@slit.lk and www.researcher.com)

Features

An opportunity to move from promises to results

The local government elections, long delayed and much anticipated, are shaping up to be a landmark political event. These elections were originally due in 2023, but were postponed by the previous government of President Ranil Wickremesinghe. The government of the day even defied a Supreme Court ruling mandating that elections be held without delay. They may have feared a defeat would erode that government’s already weak legitimacy, with the president having assumed office through a parliamentary vote rather than a direct electoral mandate following the mass protests that forced the previous president and his government to resign. The outcome of the local government elections that are taking place at present will be especially important to the NPP government as it is being accused by its critics of non-delivery of election promises.

Examples cited are failure to bring opposition leaders accused of large scale corruption and impunity to book, failure to bring a halt to corruption in government departments where corruption is known to be deep rooted, failure to find the culprits behind the Easter bombing and failure to repeal draconian laws such as the Prevention of Terrorism Act. In the former war zones of the north and east, there is also a feeling that the government is dragging its feet on resolving the problem of missing persons, those imprisoned without trial for long periods and return of land taken over by the military. But more recently, a new issue has entered the scene, with the government stating that a total of nearly 6000 acres of land in the northern province will be declared as state land if no claims regarding private ownership are received within three months.

The declaration on land to be taken over in three months is seen as an unsympathetic action by the government with an unrealistic time frame when the land in question has been held for over 30 years under military occupation and to which people had no access. Further the unclaimed land to be designated as “state land” raises questions about the motive of the circular. It has undermined the government’s election campaign in the North and East. High-level visits by the President, Prime Minister, and cabinet ministers to these regions during a local government campaign were unprecedented. This outreach has signalled both political intent and strategic calculation as a win here would confirm the government’s cross-ethnic appeal by offering a credible vision of inclusive development and reconciliation. It also aims to show the international community that Sri Lanka’s unity is not merely imposed from above but affirmed democratically from below.

Economic Incentives

In the North and East, the government faces resistance from Tamil nationalist parties. Many of these parties have taken a hardline position, urging voters not to support the ruling coalition under any circumstances. In some cases, they have gone so far as to encourage tactical voting for rival Tamil parties to block any ruling party gains. These parties argue that the government has failed to deliver on key issues, such as justice for missing persons, return of military-occupied land, release of long-term Tamil prisoners, and protection against Buddhist encroachment on historically Tamil and Muslim lands. They make the point that, while economic development is important, it cannot substitute for genuine political autonomy and self-determination. The failure of the government to resolve a land issue in the north, where a Buddhist temple has been put up on private land has been highlighted as reflecting the government’s deference to majority ethnic sentiment.

The problem for the Tamil political parties is that these same parties are themselves fractured, divided by personal rivalries and an inability to form a united front. They continue to base their appeal on Tamil nationalism, without offering concrete proposals for governance or development. This lack of unity and positive agenda may open the door for the ruling party to present itself as a credible alternative, particularly to younger and economically disenfranchised voters. Generational shifts are also at play. A younger electorate, less interested in the narratives of the past, may be more open to evaluating candidates based on performance, transparency, and opportunity—criteria that favour the ruling party’s approach. Its mayoral candidate for Jaffna is a highly regarded and young university academic with a planning background who has presented a five year plan for the development of Jaffna.

There is also a pragmatic calculation that voters may make, that electing ruling party candidates to local councils could result in greater access to state funds and faster infrastructure development. President Dissanayake has already stated that government support for local bodies will depend on their transparency and efficiency, an implicit suggestion that opposition-led councils may face greater scrutiny and funding delays. The president’s remarks that the government will find it more difficult to pass funds to local government authorities that are under opposition control has been heavily criticized by opposition parties as an unfair election ploy. But it would also cause voters to think twice before voting for the opposition.

Broader Vision

The government’s Marxist-oriented political ideology would tend to see reconciliation in terms of structural equity and economic justice. It will also not be focused on ethno-religious identity which is to be seen in its advocacy for a unified state where all citizens are treated equally. If the government wins in the North and East, it will strengthen its case that its approach to reconciliation grounded in equity rather than ethnicity has received a democratic endorsement. But this will not negate the need to address issues like land restitution and transitional justice issues of dealing with the past violations of human rights and truth-seeking, accountability, and reparations in regard to them. A victory would allow the government to act with greater confidence on these fronts, including possibly holding the long-postponed provincial council elections.

As the government is facing international pressure especially from India but also from the Western countries to hold the long postponed provincial council elections, a government victory at the local government elections may speed up the provincial council elections. The provincial councils were once seen as the pathway to greater autonomy; their restoration could help assuage Tamil concerns, especially if paired with initiating a broader dialogue on power-sharing mechanisms that do not rely solely on the 13th Amendment framework. The government will wish to capitalize on the winning momentum of the present. Past governments have either lacked the will, the legitimacy, or the coordination across government tiers to push through meaningful change.

Obtaining the good will of the international community, especially those countries with which Sri Lanka does a lot of economic trade and obtains aid, India and the EU being prominent amongst these, could make holding the provincial council elections without further delay a political imperative. If the government is successful at those elections as well, it will have control of all three tiers of government which would give it an unprecedented opportunity to use its 2/3 majority in parliament to change the laws and constitution to remake the country and deliver the system change that the people elected it to bring about. A strong performance will reaffirm the government’s mandate and enable it to move from promises to results, which it will need to do soon as mandates need to be worked at to be long lasting.

by Jehan Perera

-

News6 days ago

News6 days agoRanil’s Chief Security Officer transferred to KKS

-

Opinion4 days ago

Opinion4 days agoRemembering Dr. Samuel Mathew: A Heart that Healed Countless Lives

-

Business2 days ago

Business2 days agoAitken Spence Travels continues its leadership as the only Travelife-Certified DMC in Sri Lanka

-

Features7 days ago

Features7 days agoThe Broken Promise of the Lankan Cinema: Asoka & Swarna’s Thrilling-Melodrama – Part IV

-

News7 days ago

News7 days agoRadisson Blu Hotel, Galadari Colombo appoints Marko Janssen as General Manager

-

Business6 days ago

Business6 days agoCCPI in April 2025 signals a further easing of deflationary conditions

-

Features7 days ago

Features7 days agoA piece of home at Sri Lankan Musical Night in Dubai

-

Features6 days ago

Features6 days agoExpensive to die; worship fervour eclipses piety