Features

Ceylon’s first university in memory and imagination

OLD PERADENIYA

By Ernest Macintyre

INTRODUCTION

The Mahaweli River, 335 long, the longest river in Lanka, has its beginning in a remote village of Nuwara-Eliya District in the central hills, and ends going into the sea at the Bay of Bengal on the east coast at Trincomalee. As it passes Kandy, the main town of the central province, and goes south about six kilometers, it bends at an elbow to the shape of an arm, to cradle within an expanse of habitation born from nature accommodating Lankan classical and colonial architecture, the residential University of Ceylon, Peradeniya.

From the sandy banks of the river the richly vegetated land slopes gently upward till it reaches the old Galaha Road along which on either side, from the Botanical Gardens junction, north to the ancient Buddhist village of Hindagla ,south, are the buildings designed by architect Shirley D’ Alwis. Sir Ivor Jennings, the first Vice Chancellor took the lead in proposing and constructing the sober and dignified monument in architect Shirley D’Alwis’s honour that is situated at the first roundabout on this central road of the campus with a shallow pond all around it.

The Mahaweli from which we rose up to Galaha road is only one side of the story of nature’s promise. On the other side of Galaha, all along, the land rises further to reach in the distance, the Hantana chain of mountains. Hantana is a chain of seven mountains, surrounded by forest. From the top of the mountains is seen, at the rising of the sun, the University, faraway.

This sunrise in 1955, all was quiet on the campus. There were no students, yet. Ones already at university had four more weeks before term started. But shortly, the many hundreds of new students, those who had just gained entrance would arrive.

So we have a little time to take a walk along Galaha Road Near the village of Hindagala, in the south, where in the mid-1950s the campus ended, was the large Ramanathan Hall. It was the largest of the halls of residence, with three floors and named after Sir Ponnambalam Ramanathan who was associated with the movement for independence from Britain for the colony of Ceylon.

Turning back from Ramanathan along Galaha Road ,returning northwards, quite close to Ramanathan was Sangamitta Hall and Hilda Obeyesekere Hall, and also close by, up a hill on the Hantana side was James Peiris Hall. All three for female undergrads.

Sangamitta Hall needs a little more telling; it being the only one with a ancient historical name. Sangamitta was the title or description given to the daughter of King Ashoka of India (about 270 BC). Her name was Ayapali, and was referred to as Sangamitta when she joined the order of Buddhist nuns. Sangamitta and her brother Mahinda were sent by Ashoka their father to spread the Word of The Buddha south across India and ending in Lanka.

James Peiris and Hilda Obeyesekare whom the other two close by halls were named after, were prominent and wealthy social and political figures of the early twentieth century.

To divert now to an undergraduate activity allowable in adulthood in a residential facility of both sexes. The young men called it Kissing Bend. Despite the mischievous manipulation of language enjoyed freely in Peradeniya , Kissing Bend was not a curved part of the physical make up of one of the genders. It was an area of hard asphalt on the ground on Galaha road, where we are now on our walk through the campus.

A location of love’s reluctant closing moments of an evening after Mahaweli meetings. The Kissing Bend, with a big tree covering on one side. Kissing goodnight was just before seven in the evening, the stipulated time for women to be back in their halls, after returning from sessions close together on the banks of the Mahaveli .

young males and females, without the cultural restraint of Pirivena origin, in a university of Western imagination, allowed them freedom of nature. An old English song, ” I Met My Little Bright Eyed Doll, Down By The Riverside”, may have had its Sinhala version, much sung in Peradeniya at the time, ” Mage as deka dilisena bonikka ganga iney sambuna”, emerging from the banks of Peradeniya’s Mahaweli.

Kissing Bend was an important land mark, for as Professor Sarachchandra is reported to have once said to undergraduates: “Peradeniya is not only for passing exams, it is for the passing of young lives, at a time when it is surging.” He did not mean kissing at the bend, yet it relates to human surge and emotion in youth ,and accompanying thought, extends to works of art, which the professor had in mind. It requires imagination to extend to the surge of art, closely pressed bodies and upright, with entangled legs at Kissing Bend. Today it is probably called “imbina wangua“, with the growth of the use of Sinhala.

Moving from alongside Hilda Obeyasekara Hall now in the other direction from Hindagala, the next important structures in those times were the impressive administrative buildings, library and lecture rooms on the left and Arunachalam and Jayatileka halls side by side on the right, named again, after important political figures of the time. From Jayatitilake Hall can be seen the Shirley D’Awis memorial. Honouring the architect who in design, gave to Peradeniya man’s complement to nature. These buildings were given special mention, whatever the intention of the words mean, when the recently departed Queen of Britain and her husband Philip formally declared the University of Ceylon, open.

In the view from Jayatilleka Hall beyond this memorial was the sports grounds and tennis courts. To the right of the sports field was a makeshift accommodation, the Faculty Club. The evening club for the academic staff, who in keeping with their intellectual claims could think better with a drink. This club, apart from private homes was the only place arrack could be had on campus. The two immediate progressions from schooldays to university were ” áll but” freedom with the opposite sex and arrack. The former was easily and discreetly available, the latter prohibited on campus, yet consumed growingly, in the town of Peradeniya and the city of Kandy, bringing back its heartily displayed consumption to the campus.

Further north to the right on Galaha road, beyond Jayatilleka Hall was a narrow asphalt strip branching upwards to the seventh student residence, Marrs Hall, named after an important academic and university official, in its early Colombo University College of London days.

Seven halls of residence somewhat autonomous with an elected student president and a warden. The close social relationships were within each hall, the three meal sittings a convenient regrouping after dispersal into the larger campus body for lectures and tutorials, presided over by people who now, the years have taken away, together with some whom they lectured to, now in their mid eighties. Luudowyk, Passe, Doric de Souza, Sarachchandra, Siri Gunasinghe, H.A.de .S Gunasekara, Vaithianandan, Cuthbert Amarasinghe, Van den Driesen, Sinnappa Arasaratnam, La Brooy, Miss. Mathiaparanam and Basil Mendis. Some from the many.

The ones they educated in the mid fifties will be now in their mid eighties. The lecturers will be remembered for some time more.

Very modern the halls of residence were, with every contemporary facility students could ask for. In fact, Ramanathan Hall may have gone too far , socially inconsiderate, in installing bidets in each toilet. Small porcelain basins fixed to the floor, which spouted water upwards when its tap was opened, to serve the sitter on the bidet. Bidet is an old French word for “pony”, and was associated with Royalty ,the notion that one “rides” or straddles a bidet much like a pony is ridden. Even the Colombo “kultur” students felt more secure in their old manual methods, leaving the French “ponies” as obtrusive ornaments.

To get back to those times, we now move outside to a place that mainly served the campus. The steam train from Colombo had arrived at the small nearby Peradeniya railway station.

That morning the small station was packed with young men and women.They had come from all parts of the country. A good many were from Colombo schools. Amongst names of Sinhala and Tamil origin there were also significant numbers of Fernandos, Silvas and Pereras, resulting from the long Portuguese part of Ceylon history.

Because of free education introduced in 1948, they were well matched in numbers by those from rural Ceylon . South, Central Ceylon and North West below the Jaffna Peninsula which brought into the campus names like Deekiriwewa and Menikdiwela. TheNorth Westerners converged at Polgahawela, and then to Colombo, to change trains for Peradeniya.

The Central Province provided a mixture of Colombo and rural types. Breckenridge , Dhanapala and Senaratne are three we remember, from Trinity College and Premaratne the cricketer from Katugastota. They were not at the station, because they were close enough to Peradeniya.

There were the not so westernised Tamils from Jaffna and the Eastern Province. Not as westernised as the young Tamil men and women of the Colombo schools who had a long history of migration from Jaffna, from 1905, when the first train left Kankesanthurai for the capital city. Singhams, Lingams, Moorthys, Samys amongst others were all there at Peradeniya.

The Ceylon Moors were well spread, Colombo, Kandy, Jaffna and the Eastern Province. We remember Raheem of Royal ,Lafir and Mohamed Mustapha Ibrahim. So, the chatter on the station platform was very mixed. English, mostly from the Colombo schools and the Burghers, Sinhala from the very large area of provinces outside Colombo and Tamil from north and east.

Females, jostled with the males, in a way schoolboys and schoolgirls which they were a few months ago, had not been allowed. They would all be in close residence very soon, after transport from the station in vans. With the exception that females lived in separate halls, morning to evening they were free to be with males, including evening privacy on the banks of the Mahaweli, and at dusk, parting proximities of “Kissing Bend”.

Men together with women hiking up to Hantane in the weekends was another opportunity by which this university helped indicate, conservatively and intelligently, that men and women were meant by nature and civilization to prepare, to mate in proper time.

Significant on the station that morning was race or cultural mixing together. Peradeniya was probably the first social formation in Lanka where Sinhalese and Tamils, Ceylon Moors ,Malays and Burghers in significant numbers would actually live closely and rub shoulders with each other, sharing rooms , dining tables , sport, art , social events and academic discourse.

College House of University College, London University, had a small number of Sinhalese, Tamils and other minorities resident, but that university was largely non-residential. Government departments and commercial firms had both Sinhalese and Tamils and other ethnicities. But no institution in Lanka, before Peradeniya had thousands as one community living, day and night, closely together.

Peradeniya especially opened the opportunity for Sinhalese, Tamil, Moors, Burghers, and Malay youth to explore and conclude that they were one humanity.

Two other identifiable “cultural” groups, outside of ethnicity, that did not initially mix, that is in the 1950’s, were what students called the “O Facs” and the “Kulturs”. The students of the oriental faculties, largely from rural schools who opted for Pali, Sanskrit, Sinhala apart from Economics and History and the urban school students, mainly Colombo, Kandy, Galle and the like who did English. Latin, Greek, Economics, Western Philosophy, History.

It was unfortunate that this unreal social divide very likely created by the cultural snobbery of Colombo school products came into the campus, for it was the “O Facs” who within a year stamped Peradeniya with a cultural creation hallmarking Sri Lankan culture and launching it into South Asian recognition. Maname, a Sinhala creation that stands alongside any dramatic work, anywhere. In time this remnant colonial division imperceptibly wore out.

This day of Peradeniya also saw the last congregation of Burghers, in significant number, benefiting university contribution to the country. Though it is common to hear of Portuguese Burghers and Dutch Burghers of Ceylon, they are of varied European descent like in the composition of the mixed European De Meuron Regiment first employed by the Dutch , then serving the British and finally being disbanded in 1816 in Colombo to become part of the population From that station platform or directly onto the campus that morning, there were names like Ludowyk, Pietresz, Ondaatje, Roosmale- Cocq, Taylor, Hingert, De Zoysa, Elhart, Van der Gert, De Lay, Moldrich, Wouterz, Solomons, Jansen, Roberts, De Saram, Nicolle, Schrader, Forbes and Hepponstal. Most were unaware this morning that Peradeniya was to be only a short stopover, on their way to Melbourne.

The government’s language policy change, displacing English was a year later. Hepponstall sensed the change. He migrated to Melbourne after only one term in Peradeniya, causing Vanderdergert to quip, “What happened to Hepponstall can happen to us all”. And it eventually did. A lost tribe of Lanka. Still identifiable mainly in Melbourne.

Soon the station platform was again empty. Vans organized by the university transported the freshers to their halls of residence where a small number arriving in their parent’s cars were already establishing themselves.

A wonderful blessing of nature and human architecture was to be theirs for the next three or four years.Beyond the promise of this bend in the river on either side spread the also alluring country that sustained it. This island’s modern history, a trajectory, which Aristotle would have called a given Plot or circumstance could not leave its first university untouched, as this story will unfold.

Features

The hollow recovery: A stagnant industry – Part I

The headlines are seductive: 2.36 million tourists in 2025, a new “record.” Ministers queue for photo opportunities. SLTDA releases triumphant press statements. The narrative is simple: tourism is “back.”

The headlines are seductive: 2.36 million tourists in 2025, a new “record.” Ministers queue for photo opportunities. SLTDA releases triumphant press statements. The narrative is simple: tourism is “back.”

But scratch beneath the surface and what emerges is not a success story but a cautionary tale of an industry that has mistaken survival for transformation, volume for value, and resilience for strategy.

Problem Diagnosis: The Mirage of Recovery

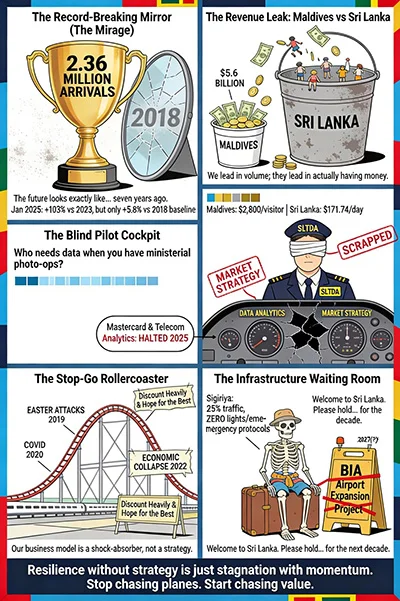

Yes, Sri Lanka welcomed 2.36 million tourists in 2025, marginally above the 2.33 million recorded in 2018. This marks a full recovery from the consecutive disasters of the Easter attacks (2019), COVID-19 (2020-21), and the economic collapse (2022). The year-on-year growth looks impressive: 15.1% above 2024’s 2.05 million arrivals.

But context matters. Between 2018 and 2023, arrivals collapsed by 36.3%, bottoming out at 1.49 million. The subsequent “rebound” is simply a return to where we were seven years ago, before COVID, before the economic crisis, even before the Easter attacks. We have spent six years clawing back to 2018 levels while competitors have leaped ahead.

Consider the monthly data. In 2023, January arrivals were just 102,545, down 57% from January 2018’s 238,924. By January 2025, arrivals reached 252,761, a dramatic 103% jump over 2023, but only 5.8% above the 2018 baseline. This is not growth; it is recovery from an artificially depressed base. Every month in 2025 shows the same pattern: strong percentage gains over the crisis years, but marginal or negative movement compared to 2018.

The problem is not just the numbers, but the narrative wrapped around them. SLTDA’s “Year in Review 2025” celebrates the 15.6% first-half increase without once acknowledging that this merely restores pre-crisis levels. The “Growth Scenarios 2025” report projects arrivals between 2.4 and 3.0 million but offers no analysis of what kind of tourism is being targeted, what yield is expected, or how market composition will shift. This is volume-chasing for its own sake, dressed up as strategic planning.

Comparative Analysis: Three Decades of Standing Still

The stagnation becomes stark when placed against Sri Lanka’s closest island competitors. In the mid-1990s, Sri Lanka, the Maldives, started from roughly the same base, around 300,000 annual arrivals each. Three decades later:

Sri Lanka: From 302,000 arrivals (1996) to 2.36 million (2025), with $3.2 billion

Maldives: From 315,000 arrivals (1995) to 2.25 million (2025), with $5.6 billion

The raw numbers obscure the qualitative difference. The Maldives deliberately crafted a luxury, high-yield model: one-island-one-resort zoning, strict environmental controls, integrated resorts layered with sustainability credentials. Today, Maldivian tourism generates approximately $5.6 billion from 2 million tourists, an average of $2,800 per visitor. The sector represents 21% of GDP and generates nearly half of government revenue.

Sri Lanka, by contrast, has oscillated between slogans, “Wonder of Asia,” “So Sri Lanka”, without embedding them in coherent policy. We have no settled model, no consensus on what kind of tourism we want, and no institutional memory because personnel and priorities change with every government. So, we match or slightly exceed competitors in arrivals, but dramatically underperform in revenue, yield, and structural resilience.

Root Causes: Governance Deficit and Policy Failure

The stagnation is not accidental; it is manufactured by systemic governance failures that successive governments have refused to confront.

1. Policy Inconsistency as Institutional Culture

Sri Lanka has rewritten its Tourism Act and produced multiple master plans since 2005. The problem is not the absence of strategy documents but their systematic non-implementation. The National Tourism Policy approved in February 2024 acknowledges that “policies and directions have not addressed several critical issues in the sector” and that there was “no commonly agreed and accepted tourism policy direction among diverse stakeholders.”

This is remarkable candor, and a damning indictment. After 58 years of organised tourism development, we still lack policy consensus. Why? Because tourism policy is treated as political property, not national infrastructure. Changes in government trigger wholesale personnel changes at SLTDA, Tourism Ministry, and SLTPB. Institutional knowledge evaporates. Priorities shift with ministerial whims. Therefore, operators cannot plan, investors cannot commit, and the industry lurches from crisis response to crisis response without building structural resilience.

2. Fragmented Institutional Architecture

Tourism responsibilities are scattered across the Ministry of Tourism, Sri Lanka Tourism Development Authority (SLTDA), Sri Lanka Tourism Promotion Bureau (SLTPB), provincial authorities, and an ever-expanding roster of ad hoc committees. The ADB’s 2024 Tourism Sector Diagnostics bluntly notes that “governance and public infrastructure development of tourism in Sri Lanka is fragmented and hampered.”

Tourism responsibilities are scattered across the Ministry of Tourism, Sri Lanka Tourism Development Authority (SLTDA), Sri Lanka Tourism Promotion Bureau (SLTPB), provincial authorities, and an ever-expanding roster of ad hoc committees. The ADB’s 2024 Tourism Sector Diagnostics bluntly notes that “governance and public infrastructure development of tourism in Sri Lanka is fragmented and hampered.”

No single institution owns yield. No one is accountable for net foreign exchange contribution after leakages. Quality standards are unenforced. The tourism development fund, 1% of the tourism levy plus embarkation taxes, is theoretically allocated 70% to SLTPB for global promotion, but “lengthy procurement and approval processes” render it ineffective.

Critically, the current government has reportedly scrapped sophisticated data analytics programmes that were finally giving SLTDA visibility into spending patterns, high-yield segments, and tourist movement. According to industry reports in late 2025, partnerships with entities like Mastercard and telecom data analytics have been halted, forcing the sector to fly blind precisely when data-driven decision-making is essential.

3. Infrastructure Deficit and Resource Misallocation

The Bandaranaike International Airport Development Project, essential for handling projected tourist volumes, has been repeatedly delayed. Originally scheduled for completion years ago, it is now re-tendered for 2027 delivery after debt restructuring. Meanwhile, tourists in late 2025 faced severe congestion at BIA, with reports of near-miss flights due to immigration and check-in bottlenecks.

At cultural sites, basic facilities are inadequate. Sigiriya, which generates approximately 25% of cultural tourist traffic and charges $36 per visitor, lacks adequate lighting, safety measures, and emergency infrastructure. Tourism associations report instances of tourists being attacked by wild elephants with no effective safety protocols.

SLTDA Chairman statements acknowledge “many restrictions placed on incurring capital expenditure” and “embargoes placed not only on tourism but all Government institutions.” The frank admission: we lack funds to maintain the assets that generate revenue. This is governance failure in its purest form, allowing revenue-generating infrastructure to decay while chasing arrival targets.

The Stop-Go Trap: Volatility as Business Model

What truly differentiates Sri Lanka from competitors is not arrival levels but the pattern: extreme stop-go volatility driven by crisis and short-term stimulus rather than steady, strategic growth.

After each shock, the industry is told to “bounce back” without being given the tools to build resilience. The rebound mechanism is consistent: currency depreciation makes Sri Lanka “affordable,” operators discount aggressively to fill rooms, and visa concessions attract price-sensitive segments. Arrivals recover, until the next shock.

This is not how a strategic export industry operates. It is how a shock-absorber behaves, used to plug forex and fiscal holes after each policy failure, then left exposed again.

The monthly 2023-2025 data illustrate the cycle perfectly. Between January 2018 and January 2023, arrivals fell 57%. The “recovery” to January 2025 shows a 103% jump over 2023, but this is bounce-back from an artificially depressed base, not structural transformation. By September 2025, growth rates normalize into the teens and twenties, catch-up to a benchmark set six years earlier.

Why the Boom Feels Like Stagnation

Industry operators report a disconnect between headline numbers and ground reality. Occupancy rates have improved to the high-60% range, but margins remain below 2018 levels. Why?

Industry operators report a disconnect between headline numbers and ground reality. Occupancy rates have improved to the high-60% range, but margins remain below 2018 levels. Why?

Because input costs, energy, food, debt servicing, have risen faster than room rates. The rupee’s collapse makes Sri Lanka look “affordable” to foreigners, but it quietly transfers value from domestic suppliers and workers to foreign visitors and lenders. Hotels fill rooms at prices that barely cover costs once translated into hard currency and adjusted for inflation.

Growth is fragile and concentrated. Europe and Asia-Pacific account for over 92% of arrivals. India alone provides 20.7% of visitors in H1 2025, and as later articles in this series will show, this is a low-yield, short-stay segment. We have built recovery on market concentration and price competition, not on product differentiation or yield optimization.

There is no credible long-term roadmap. SLTDA’s projections focus almost entirely on volumes. There is no public discussion of receipts-per-visitor targets, market composition strategies, or institutional reforms required to shift from volume to value.

The Way Forward: From Arrivals Theater to Strategic Transformation

The path out of stagnation requires uncomfortable honesty and political courage that has been systematically absent.

First, abandon arrivals as the primary success metric. Tourism contribution to economic recovery should be measured by net foreign exchange contribution after leakages, employment quality (wages, stability), and yield per visitor, not by how many planes land.

Second, establish institutional continuity. Depoliticize relevant leaderships. Implement fixed terms for key personnel insulated from political cycles. Tourism is a 30-year investment horizon; it cannot be managed on five-year electoral cycles.

Third, restore data infrastructure. Reinstate the analytics programs that track spending patterns and identify high-yield segments. Without data, we are flying blind, and no amount of ministerial optimism changes that.

Fourth, allocate resources to infrastructure. The tourism development fund exists, use it. Online promotions, BIA expansion, cultural site upgrades, last-mile connectivity cannot wait for “better fiscal conditions.” These assets generate the revenue that funds their own maintenance.

Resilience without strategy is stagnation with momentum. And stagnation, however energetically celebrated, remains stagnation.

If policymakers continue to mistake arrivals for achievement, Sri Lanka will remain trapped in a cycle: crash, discount, recover, repeat. Meanwhile, competitors will consolidate high-yield models, and we will wonder why our tourism “boom” generates less cash, less jobs, and less development than it should.

(The writer, a senior Chartered Accountant and professional banker, is Professor at SLIIT, Malabe. The views and opinions expressed in this article are personal.)

Features

The call for review of reforms in education: discussion continues …

The hype around educational reforms has abated slightly, but the scandal of the reforms persists. And in saying scandal, I don’t mean the error of judgement surrounding a misprinted link of an online dating site in a Grade 6 English language text book. While that fiasco took on a nasty, undeserved attack on the Minister of Education and Prime Minister Harini Amarasuriya, fundamental concerns with the reforms have surfaced since then and need urgent discussion and a mechanism for further analysis and action. Members of Kuppi have been writing on the reforms the past few months, drawing attention to the deeply troubling aspects of the reforms. Just last week, a statement, initiated by Kuppi, and signed by 94 state university teachers, was released to the public, drawing attention to the fundamental problems underlining the reforms https://island.lk/general-educational-reforms-to-what-purpose-a-statement-by-state-university-teachers/. While the furore over the misspelled and misplaced reference and online link raged in the public domain, there were also many who welcomed the reforms, seeing in the package, a way out of the bottle neck that exists today in our educational system, as regards how achievement is measured and the way the highly competitive system has not helped to serve a population divided by social class, gendered functions and diversities in talent and inclinations. However, the reforms need to be scrutinised as to whether they truly address these concerns or move education in a progressive direction aimed at access and equity, as claimed by the state machinery and the Minister… And the answer is a resounding No.

The hype around educational reforms has abated slightly, but the scandal of the reforms persists. And in saying scandal, I don’t mean the error of judgement surrounding a misprinted link of an online dating site in a Grade 6 English language text book. While that fiasco took on a nasty, undeserved attack on the Minister of Education and Prime Minister Harini Amarasuriya, fundamental concerns with the reforms have surfaced since then and need urgent discussion and a mechanism for further analysis and action. Members of Kuppi have been writing on the reforms the past few months, drawing attention to the deeply troubling aspects of the reforms. Just last week, a statement, initiated by Kuppi, and signed by 94 state university teachers, was released to the public, drawing attention to the fundamental problems underlining the reforms https://island.lk/general-educational-reforms-to-what-purpose-a-statement-by-state-university-teachers/. While the furore over the misspelled and misplaced reference and online link raged in the public domain, there were also many who welcomed the reforms, seeing in the package, a way out of the bottle neck that exists today in our educational system, as regards how achievement is measured and the way the highly competitive system has not helped to serve a population divided by social class, gendered functions and diversities in talent and inclinations. However, the reforms need to be scrutinised as to whether they truly address these concerns or move education in a progressive direction aimed at access and equity, as claimed by the state machinery and the Minister… And the answer is a resounding No.

The statement by 94 university teachers deplores the high handed manner in which the reforms were hastily formulated, and without public consultation. It underlines the problems with the substance of the reforms, particularly in the areas of the structure of education, and the content of the text books. The problem lies at the very outset of the reforms, with the conceptual framework. While the stated conceptualisation sounds fancifully democratic, inclusive, grounded and, simultaneously, sensitive, the detail of the reforms-structure itself shows up a scandalous disconnect between the concept and the structural features of the reforms. This disconnect is most glaring in the way the secondary school programme, in the main, the junior and senior secondary school Phase I, is structured; secondly, the disconnect is also apparent in the pedagogic areas, particularly in the content of the text books. The key players of the “Reforms” have weaponised certain seemingly progressive catch phrases like learner- or student-centred education, digital learning systems, and ideas like moving away from exams and text-heavy education, in popularising it in a bid to win the consent of the public. Launching the reforms at a school recently, Dr. Amarasuriya says, and I cite the state-owned broadside Daily News here, “The reforms focus on a student-centered, practical learning approach to replace the current heavily exam-oriented system, beginning with Grade One in 2026 (https://www.facebook.com/reel/1866339250940490). In an address to the public on September 29, 2025, Dr. Amarasuriya sings the praises of digital transformation and the use of AI-platforms in facilitating education (https://www.facebook.com/share/v/14UvTrkbkwW/), and more recently in a slightly modified tone (https://www.dailymirror.lk/breaking-news/PM-pledges-safe-tech-driven-digital-education-for-Sri-Lankan-children/108-331699).

The idea of learner- or student-centric education has been there for long. It comes from the thinking of Paulo Freire, Ivan Illyich and many other educational reformers, globally. Freire, in particular, talks of learner-centred education (he does not use the term), as transformative, transformative of the learner’s and teacher’s thinking: an active and situated learning process that transforms the relations inhering in the situation itself. Lev Vygotsky, the well-known linguist and educator, is a fore runner in promoting collaborative work. But in his thought, collaborative work, which he termed the Zone of Proximal Development (ZPD) is processual and not goal-oriented, the way teamwork is understood in our pedagogical frameworks; marks, assignments and projects. In his pedagogy, a well-trained teacher, who has substantial knowledge of the subject, is a must. Good text books are important. But I have seen Vygotsky’s idea of ZPD being appropriated to mean teamwork where students sit around and carry out a task already determined for them in quantifying terms. For Vygotsky, the classroom is a transformative, collaborative place.

But in our neo liberal times, learner-centredness has become quick fix to address the ills of a (still existing) hierarchical classroom. What it has actually achieved is reduce teachers to the status of being mere cogs in a machine designed elsewhere: imitative, non-thinking followers of some empty words and guide lines. Over the years, this learner-centred approach has served to destroy teachers’ independence and agency in designing and trying out different pedagogical methods for themselves and their classrooms, make input in the formulation of the curriculum, and create a space for critical thinking in the classroom.

Thus, when Dr. Amarasuriya says that our system should not be over reliant on text books, I have to disagree with her (https://www.newsfirst.lk/2026/01/29/education-reform-to-end-textbook-tyranny ). The issue is not with over reliance, but with the inability to produce well formulated text books. And we are now privy to what this easy dismissal of text books has led us into – the rabbit hole of badly formulated, misinformed content. I quote from the statement of the 94 university teachers to illustrate my point.

“The textbooks for the Grade 6 modules . . . . contain rampant typographical errors and include (some undeclared) AI-generated content, including images that seem distant from the student experience. Some textbooks contain incorrect or misleading information. The Global Studies textbook associates specific facial features, hair colour, and skin colour, with particular countries and regions, and refers to Indigenous peoples in offensive terms long rejected by these communities (e.g. “Pygmies”, “Eskimos”). Nigerians are portrayed as poor/agricultural and with no electricity. The Entrepreneurship and Financial Literacy textbook introduces students to “world famous entrepreneurs”, mostly men, and equates success with business acumen. Such content contradicts the policy’s stated commitment to “values of equity, inclusivity and social justice” (p. 9). Is this the kind of content we want in our textbooks?”

Where structure is concerned, it is astounding to note that the number of subjects has increased from the previous number, while the duration of a single period has considerably reduced. This is markedly noticeable in the fact that only 30 hours are allocated for mathematics and first language at the junior secondary level, per term. The reduced emphasis on social sciences and humanities is another matter of grave concern. We have seen how TV channels and YouTube videos are churning out questionable and unsubstantiated material on the humanities. In my experience, when humanities and social sciences are not properly taught, and not taught by trained teachers, students, who will have no other recourse for related knowledge, will rely on material from controversial and substandard outlets. These will be their only source. So, instruction in history will be increasingly turned over to questionable YouTube channels and other internet sites. Popular media have an enormous influence on the public and shapes thinking, but a well formulated policy in humanities and social science teaching could counter that with researched material and critical thought. Another deplorable feature of the reforms lies in provisions encouraging students to move toward a career path too early in their student life.

The National Institute of Education has received quite a lot of flak in the fall out of the uproar over the controversial Grade 6 module. This is highlighted in a statement, different from the one already mentioned, released by influential members of the academic and activist public, which delivered a sharp critique of the NIE, even while welcoming the reforms (https://ceylontoday.lk/2026/01/16/academics-urge-govt-safeguard-integrity-of-education-reforms). The government itself suspended key players of the NIE in the reform process, following the mishap. The critique of NIE has been more or less uniform in our own discussions with interested members of the university community. It is interesting to note that both statements mentioned here have called for a review of the NIE and the setting up of a mechanism that will guide it in its activities at least in the interim period. The NIE is an educational arm of the state, and it is, ultimately, the responsibility of the government to oversee its function. It has to be equipped with qualified staff, provided with the capacity to initiate consultative mechanisms and involve panels of educators from various different fields and disciplines in policy and curriculum making.

In conclusion, I call upon the government to have courage and patience and to rethink some of the fundamental features of the reform. I reiterate the call for postponing the implementation of the reforms and, in the words of the statement of the 94 university teachers, “holistically review the new curriculum, including at primary level.”

(Sivamohan Sumathy was formerly attached to the University of Peradeniya)

Kuppi is a politics and pedagogy happening on the margins of the lecture hall that parodies, subverts, and simultaneously reaffirms social hierarchies.

By Sivamohan Sumathy

Features

Constitutional Council and the President’s Mandate

The Constitutional Council stands out as one of Sri Lanka’s most important governance mechanisms particularly at a time when even long‑established democracies are struggling with the dangers of executive overreach. Sri Lanka’s attempt to balance democratic mandate with independent oversight places it within a small but important group of constitutional arrangements that seek to protect the integrity of key state institutions without paralysing elected governments. Democratic power must be exercised, but it must also be restrained by institutions that command broad confidence. In each case, performance has been uneven, but the underlying principle is shared.

Comparable mechanisms exist in a number of democracies. In the United Kingdom, independent appointments commissions for the judiciary and civil service operate alongside ministerial authority, constraining but not eliminating political discretion. In Canada, parliamentary committees scrutinise appointments to oversight institutions such as the Auditor General, whose independence is regarded as essential to democratic accountability. In India, the collegium system for judicial appointments, in which senior judges of the Supreme Court play the decisive role in recommending appointments, emerged from a similar concern to insulate the judiciary from excessive political influence.

The Constitutional Council in Sri Lanka was developed to ensure that the highest level appointments to the most important institutions of the state would be the best possible under the circumstances. The objective was not to deny the executive its authority, but to ensure that those appointed would be independent, suitably qualified and not politically partisan. The Council is entrusted with oversight of appointments in seven critical areas of governance. These include the judiciary, through appointments to the Supreme Court and Court of Appeal, the independent commissions overseeing elections, public service, police, human rights, bribery and corruption, and the office of the Auditor General.

JVP Advocacy

The most outstanding feature of the Constitutional Council is its composition. Its ten members are drawn from the ranks of the government, the main opposition party, smaller parties and civil society. This plural composition was designed to reflect the diversity of political opinion in Parliament while also bringing in voices that are not directly tied to electoral competition. It reflects a belief that legitimacy in sensitive appointments comes not only from legal authority but also from inclusion and balance.

The idea of the Constitutional Council was strongly promoted around the year 2000, during a period of intense debate about the concentration of power in the executive presidency. Civil society organisations, professional bodies and sections of the legal community championed the position that unchecked executive authority had led to abuse of power and declining public trust. The JVP, which is today the core part of the NPP government, was among the political advocates in making the argument and joined the government of President Chandrika Bandaranaike Kumaratunga on this platform.

The first version of the Constitutional Council came into being in 2001 with the 17th Amendment to the Constitution during the presidency of Chandrika Bandaranaike Kumaratunga. The Constitutional Council functioned with varying degrees of effectiveness. There were moments of cooperation and also moments of tension. On several occasions President Kumaratunga disagreed with the views of the Constitutional Council, leading to deadlock and delays in appointments. These experiences revealed both the strengths and weaknesses of the model.

Since its inception in 2001, the Constitutional Council has had its ups and downs. Successive constitutional amendments have alternately weakened and strengthened it. The 18th Amendment significantly reduced its authority, restoring much of the appointment power to the executive. The 19th Amendment reversed this trend and re-established the Council with enhanced powers. The 20th Amendment again curtailed its role, while the 21st Amendment restored a measure of balance. At present, the Constitutional Council operates under the framework of the 21st Amendment, which reflects a renewed commitment to shared decision making in key appointments.

Undermining Confidence

The particular issue that has now come to the fore concerns the appointment of the Auditor General. This is a constitutionally protected position, reflecting the central role played by the Auditor General’s Department in monitoring public spending and safeguarding public resources. Without a credible and fearless audit institution, parliamentary oversight can become superficial and corruption flourishes unchecked. The role of the Auditor General’s Department is especially important in the present circumstances, when rooting out corruption is a stated priority of the government and a central element of the mandate it received from the electorate at the presidential and parliamentary elections held in 2024.

So far, the government has taken hitherto unprecedented actions to investigate past corruption involving former government leaders. These actions have caused considerable discomfort among politicians now in the opposition and out of power. However, a serious lacuna in the government’s anti-corruption arsenal is that the post of Auditor General has been vacant for over six months. No agreement has been reached between the government and the Constitutional Council on the nominations made by the President. On each of the four previous occasions, the nominees of the President have failed to obtain its concurrence.

The President has once again nominated a senior officer of the Auditor General’s Department whose appointment was earlier declined by the Constitutional Council. The key difference on this occasion is that the composition of the Constitutional Council has changed. The three representatives from civil society are new appointees and may take a different view from their predecessors. The person appointed needs to be someone who is not compromised by long years of association with entrenched interests in the public service and politics. The task ahead for the new Auditor General is formidable. What is required is professional competence combined with moral courage and institutional independence.

New Opportunity

By submitting the same nominee to the Constitutional Council, the President is signaling a clear preference and calling it to reconsider its earlier decision in the light of changed circumstances. If the President’s nominee possesses the required professional qualifications, relevant experience, and no substantiated allegations against her, the presumption should lean toward approving the appointment. The Constitutional Council is intended to moderate the President’s authority and not nullify it.

A consensual, collegial decision would be the best outcome. Confrontational postures may yield temporary political advantage, but they harm public institutions and erode trust. The President and the government carry the democratic mandate of the people; this mandate brings both authority and responsibility. The Constitutional Council plays a vital oversight role, but it does not possess an independent democratic mandate of its own and its legitimacy lies in balanced, principled decision making.

Sri Lanka’s experience, like that of many democracies, shows that institutions function best when guided by restraint, mutual respect, and a shared commitment to the public good. The erosion of these values elsewhere in the world demonstrates their importance. At this critical moment, reaching a consensus that respects both the President’s mandate and the Constitutional Council’s oversight role would send a powerful message that constitutional governance in Sri Lanka can work as intended.

by Jehan Perera

-

Opinion6 days ago

Opinion6 days agoSri Lanka, the Stars,and statesmen

-

Business7 days ago

Business7 days agoClimate risks, poverty, and recovery financing in focus at CEPA policy panel

-

Business5 days ago

Business5 days agoHayleys Mobility ushering in a new era of premium sustainable mobility

-

Business2 days ago

Business2 days agoSLIM-Kantar People’s Awards 2026 to recognise Sri Lanka’s most trusted brands and personalities

-

Business5 days ago

Business5 days agoAdvice Lab unveils new 13,000+ sqft office, marking major expansion in financial services BPO to Australia

-

Business5 days ago

Business5 days agoArpico NextGen Mattress gains recognition for innovation

-

Business4 days ago

Business4 days agoAltair issues over 100+ title deeds post ownership change

-

Business4 days ago

Business4 days agoSri Lanka opens first country pavilion at London exhibition