Opinion

Buddhist meditation for the tech-savvy generation

By Geewananda Gunawardana, Ph.D.

Meditation is a two-billion-dollar industry in the USA; it includes retreats, corporate training classes, apps, and many variations in between. It is estimated that 14% of adults have participated in meditation at least once in their lifetime. A survey found that 22% of the participants meditate to connect with their “true self” and 10% to connect with something larger than themselves, i.e., spiritual reasons. It is fair to assume that most of the Sri Lankan Buddhists would belong to this category. Another 16% meditate for health and enjoyment; the other reasons are improving energy, aiding memory or concentration, anxiety, stress, addiction, and depression (Science Reports 2016). The corporations do it to increase the productivity of their employees, i.e., to make more money.

While some participants have reported positive outcomes, others claim disappointments, misunderstandings, and undesired outcomes. Bhikkhu Sujato explained all this when he wrote: “While the intensive retreat has given many people, including myself, a crucial kick-start in their Dhamma practice, it is not without its drawbacks. It is normal that meditators will get a high on the retreat and then fall back to earth. The extreme exertion invites over-estimation, and such retreats are full of people who convince themselves they have attained jhāna or awakening. Even worse, intensive practice with inadequate preparation and guidance can trigger psychosis, which is extremely dangerous. Many meditation retreats are run without the grounding in psychological understanding to recognize or handle these breakdowns, and meditators may be told simply to continue, or even that their psychosis is a sign of insight” (Bhikkhu Sujato, Sutta Central 2013).

My meditating colleagues who know my Theravada background often ask about my opinion on the ‘Mindfulness” sessions we were offered. What miracle is expected to happen when you focus on your breath or some other object while sitting still, they ask. I am no meditation guru, and I am as conflicted as they are; as I understand it, the Buddhist meditation is based on the fundamentals of Buddha’s teaching. It has a clear goal, but no mystery or magic of any kind. Numerous other methods have been added over the years. It is no wonder that one can become confused if one gets into meditation without knowing the fundamentals. That is the case with most American meditators, just as Bhikkhu Sujato has explained, but are we Sri Lankans any better?

The Buddha’s mission was to eliminate doubts and mysticism from traditional explanations and theories of life that existed during his time, and his solution is expressed as “Seeing things as they really are” (yathabutha nanadassana). This is further elaborated as to “Understand the nature of the universe and the humans’ place in it, without subscribing to superhuman powers or mysticism” (Kalupahana 1992). Therefore, the goal is to understand this at the supreme level, which is Nibbana. The method is described in the Fourth Noble Truth, the Eightfold Path.

This is where the technologically savvy generation can step up. While earlier generations used perceptions and logical inferences to understand the nature of the universe and humans’ place in it, today, science is using experimental methods to achieve the same goal. This effort has generated a vast amount of information on subjects relevant to Buddhist meditation and described them in terms relatable to the present generation. Even high schoolers learn some of these facts, but unfortunately, they are not trained to see their relevance to real life beyond box checking at the examination. Therefore, the challenge for the tech savvy generation is to convert that information into knowledge and knowledge into wisdom, or insight, a form of meditation, as I was told by my mentors.

The traditionalists will scoff at this idea, but the Buddha himself used parables, similes, and stories appropriate for the times to get the message across. He acknowledged that while there is only one truth, there are many ways to reach it. Today, scientific knowledge is the best and most accessible tool to relate to Buddha’s teaching. What is wrong with adding one more to the forty plus existing methods if it works? The Pali term bhavana means mental culture or mental development to be able to see things as they really are. Various methods for the development of mental concentration (samatha or samadhi) existed before Buddha’s time, which he practiced under various teachers before the enlightenment. Buddha found them to be unsatisfactory as they did not lead to the realization of the truth, so he discovered his own method, the insight meditation (vipassana).

There is one more point to remember. Most meditation practices being popularized were originally meant for monastics and not for the laity (Sujato, 2013), and others were developed by 20th century meditation experts. The Pali Canon and the exegesis are transmitted over the millennia by the male monastic community, and as a result, what was meant for the laity has been mostly deemphasized or completely omitted from current practices (B. Rahula 2008). Furthermore, those methods were developed based on conclusions drawn by applying critical thinking and reasoning to information available at the time. On the other hand, modern science has added vast amounts of empirical information about the nature of things that were not available to the previous generations, which can be used for meditation. That does not mean that the other methods are invalid, or the Buddhist thinking is inferior to science. It is quite the opposite: science is only beginning to rediscover what the Buddha described two and a half millennia ago, without the benefit of ‘sophisticated’ technology, especially about the human perception and mind. Therefore, scientific understanding of the human body, mind, and the universe offers the technologically savvy generation yet another way to relate to Buddhist ideals without subscribing to conjecture, mysticism or beliefs.

The Buddhist meditation is aimed at gaining insight, which is described as paying attention or observation (anupassana) into the true nature of the body (kaya), perception (vedana), mind (citta), and several other phenomena (dhamma) that include the three characteristics of life and factors governing morals or ethics (DN 22, and MN 10). Except for the subject of mind, science has explored and explained every detail of these subjects going down to subatomic particles level. While Buddhist teaching is way ahead in explaining the mind, science has made great advances in catching up during the last two decades, and their findings are astonishingly in agreement with what the Buddha taught.

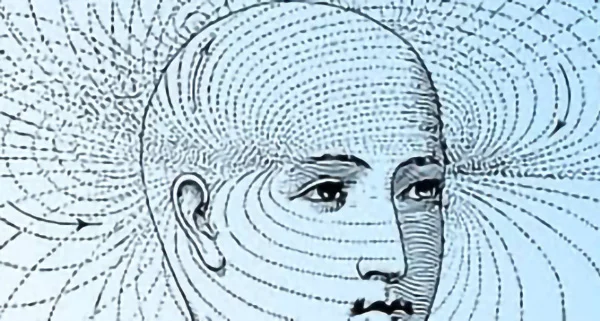

The relevant facts that would emerge from the investigation of scientific information can be summarized as follows. All phenomena, animate and inanimate, in this universe, except one, arise due to causes and conditions, and as a result, they are all interrelated (hethuphala vada). Therefore, all such phenomena are in flux (anicca), and have no substance (anatta), i.e., they are all processes. The human sensory system is evolved for the sole purpose of perpetuating their DNA, and as a result their perception (vedana) is imperfect and not suited for seeing the reality. The brain processes (citta) this incomplete information received as electro-chemical signals and constructs a mental image of the universe. We have no way of knowing how accurate that model is, except that it is good enough for the intended purpose, which is the propagation of DNA. This limitation of observing reality is further elaborated in quantum mechanics.

Humans are compelled to navigate through this world, of which they have only a mental construct of unknown quality, using tools built for different purposes. This is like a blindfolded man on a bullock cart with a broken axel is asked to navigate through a busy modern city. However unsatisfactory and beyond control the situation is, evolutionary processes have made humans cling to this situation (tanha). As a result of this clinging, humans continue to plod through it, assuming it is fun, again a trick of the DNA; this is referred to as the human condition (dukkha). While the immediate cause of this condition is the clinging, Buddha explained that the cause of clinging is ignorance (avijja), and the way to be free from this human condition is to eliminate ignorance and see things as they really are. The mental culture or development (vipassana bhavana) is the necessary mechanism to achieve this wisdom.

The Noble Eight-fold Path is interpreted by scholars as having two meanings: it is the way to become a noble, i.e., one with wisdom, and it is the way the nobles behave. As the name implies, the path has eight categories, which must be followed and practiced concurrently. These eight divisions belong to three types: wisdom (panna), mental discipline (samadhi), and ethical conduct (sila). Wisdom includes having the right thoughts (sankappa) and understanding, or view (ditthi) of the above-described processes. Having mental discipline includes striving (vayama) to be focused (samadhi) and mindful (sati) of all actions. In other words, know how the universe functions and ensure one’s speech (vaca), actions (kammanata), and livelihood (ajiva) are in harmony with the universe, which is ethical conduct.

None of the above processes have anything to do with beliefs, mysticism, or ideology. All these phenomena are explained based on empirical evidence by the theory of molecular evolution, biology, neuroscience, and physics. The premise is that one who understands these phenomena in wisdom will live a happy and a harmonious life as they know that all phenomena are interconnected and his or her actions have consequences, not only for the individual, but all beings. This is not a mere hypothesis but an empirically proven fact. Today, in this technologically advanced society, where information is freely available, individuals can access all the relevant information at levels befitting to their individual needs, including original publications in scientific journals. One does not have to retreat from daily life, sit in a particular posture, or take the words of someone else to verify these facts. Recall the Buddha’s advice to Kalalmas.

While the Buddha did not rule out the ability of laity to achieve insight at the supreme level, he gave a more pragmatic option for them: an ethical and moral code of conduct referred to as the Five Precepts, for leading a happy and harmonious life. There is a particularly important reason for giving two different prescriptions for monastics and laity. Laity must deal with a variety of responsibilities and chores constantly and require interacting with a larger community, whereas monastics remain mostly isolated from such hassles and chores. Therefore, for the laity to live a harmonious life, the entire community must abide by rules, regulations, and conduct accepted by the community. Buddhist ethics, especially the five precepts, are not based on some doctrinal principles, but are formulated for the welfare of the community at large and its needs and wants. These secular principles are based on the following rationale: If someone were to do “this thing to me,” I would not like it. But if I were to do it to them, they would not like it either. The thing that is disliked by me is also disliked by another. Since I dislike this thing, how can I inflict it on another (SN 55.7).

Unfortunately, many Buddhists believe that the consequences of either following or breaking the five precepts will come to fruition only in the next life. That is not the case, they are related to the wellbeing of a society here and now. Imagine where Sri Lanka would be today if the elected officials and bureaucrats had observed the second precept of refraining from taking what is not given to them. What if the religious leaders had used their authority to stop these blatant violations or at least condemn them, instead of bestowing their blessings? If the same people had followed the fourth precept of refraining from false speech, would there be a need to fight for transparency? Following the five precepts can help solve most of the ills of society; but one must see the science behind it and act, accordingly, merely parroting them in a dead language will not help. Furthermore, it is necessary to interpret the Buddhist code of conduct in the current context. If the tech savvy generation cannot see it, what is the use of all that knowledge?

For example, most Theravadin Buddhists assume that eating meat does not violate the first of the five precepts: refraining from depriving a living being of its life. Their reasoning is that I did not kill the animal, and meat is always available in the market. That is an erroneous assumption; free market economist will explain that the animals are slaughtered specifically for the customers’ needs. The point is that the negative consequences of meat eating are severe and far reaching. It is an extremely inefficient way of gaining nutriment. It takes seven kilograms of grains to produce one kilogram of beef. The worldwide grain harvest used for animal feed is sufficient to feed ten billion people, which is the expected world population in the year 2050. The land and water use, deforestation, antibiotic use, habitat loss, and the contribution to greenhouse gas emissions of animal farming are already beyond sustainable levels.

The best and the easiest way to help reduce global warming is to reduce meat consumption so that burning of fossil fuels can be continued until an alternative is found. The negative health effects and associated costs, especially in societies that have taken up the habit due to newfound wealth, should be considered as well. The West has seen it, and they are acting on it. Practicing the first precept could be our only, and the least disruptive contribution to achieving carbon neutrality by 2050.

Sri Lanka is one of the most corrupt countries, we scored thirty-four out of one hundred (Transparency International 2023). It is not necessary to explain the consequences of not refraining from taking what is not given by others and false speech. Sadly, our culture has a long history of pleasing those in positions of power or authority (Knox 1681) and it has now become a national norm with disastrous results.

Sri Lanka’s alcohol consumption is 4.1 litres per capita. However, when corrected for the drinking population, which is 34.8%, it becomes a staggering number. This has been identified as a major obstacle to achieving the country’s Sustainable Development Goals (PLoS One. 2018; 13(6). Asides from adverse economic and health issues – no, there are no known health benefits from moderate drinking whatsoever, abuse of mind-altering substances can have devastating effects on families, especially children, friends, and the community in general. It is important to know that it is not only alcohol, tobacco, and illicit drugs that come under this category, but the harmless betel nut too can alter the mind to a certain degree; they all hinder the rational thinking ability, quite the opposite of culture or development of mind.

Next to the second and fourth precepts, the most damage to society results from disregarding the third precept: renouncing sexual misconduct. This is often interpreted as refraining from adultery, which is incorrect. English translations of the Pali verse use misconduct, illicit, unacceptable, and misuse; therefore, a better interpretation would be “not to use sexuality in any way that can cause harm to others, self, or society.” A number of other social ills prevalent in the country fall under this definition: According to a UN report, 90% of the women surveyed report being sexually harassed at least once in their lifetime. That number for late adolescent school children is 78%. A survey of men found that 28% of them were sexually abused during childhood. The actual numbers could be higher; many victims remain silent as they do not wish to re-live the trauma. This is a disgusting situation; how can a society function if half of its members must live in constant fear of the other half? That is a pathetic commentary for a nation claiming to have a proud civilization and be the protectors of the Buddha’s teaching. A civilization, really?

How did a society that has access to a wealth of information that is ahead of modern science get into this situation? It is a multifactorial issue. We carry a lot of baggage, and old habits are hard to change; for example, offering gifts to nobility to get things done is not new (Knox 1681), but now it has grown into a dangerous cancer consuming the nation. Recall that both giver and taker are committing crimes. In the context of this discussion, I attribute the responsibility to failures of the education system and the inability of the monastic society to accept and admit that their tradition has been hijacked by external forces and transformed it beyond recognition (Is the Buddha’s teaching lost on us? Island 05/12/2023). Teaching children to recite the five precepts in a dead language without emphasizing the science behind it serves no purpose. Only when one knows the true meaning of them, he or she will have no doubt about the validity of observing them to the letter.

The generation brought up with emphasis on STEM education has a chance to change the system; in reality, they have no other choice. Yes, the governance system must be changed, but ethics and morals cannot be legalized (legal positivism). Even though it is neglected and desecrated, they have access to the teachings of the greatest ethicists the world has known. Buddha’s teaching is a true user manual for the human. Unfortunately, it is used as a “manthra” that imparts good luck or mystic powers. Instead of memorizing Asvagosha’s poem, for example, the tech savvy generation must see the pragmatism of the Dhamma that gives the knowledge and the tools to deal with the mental and physical challenges humans face while navigating through the complex world they have inherited.

Buddha dhamma is an exploration of the universe and the humans’ place in it. It is a highly scientific explanation of the human body, mind, and other related phenomena, but one must see it in wisdom, without the mysticism, rituals, and misguided commentaries. The tech savvy generation has a wonderful opportunity to see the science behind it and gain the skill set to solve the problems at hand. As I was told, that is the Buddhist mediation is all about. If one can see the said processes that constitute the body and mind “without word or label,” they have succeeded. At that point, they will also see the relevance of morals in the Buddhist concept of continuity. Unfortunately, we cannot expect any help in this effort from those who advocate kayanu passana but oppose teaching children how to use their body and mind. To be fair, it is not reasonable for us to expect them to have an in-depth knowledge of biochemistry or neuroscience.

Opinion

Labour exploitation at Sri Lankan audit firms: A regulatory blind spot

A recent tragedy of a young audit professional has prompted a nationwide conversation on Sri Lanka’s audit work culture. What was initially described as an untimely passing has since raised serious concerns about excessive workloads, workplace responsibility, and the well-being implications of the professional pressure. Accordingly, this article seeks to explore prevailing audit culture and professional practices in Sri Lanka, and highlights areas where thoughtful reform may be considered

The Evolution of Accounting and Finance Education in Sri Lanka

Over the past several decades, accounting and finance education in Sri Lanka has evolved from a narrowly technical field into a recognised professional discipline. Universities and professional institutions now offer specialised programmes aligned with international standards, covering accounting, finance, auditing, taxation, and corporate governance.

Professional bodies have modernised curricula by incorporating international accounting and auditing standards, ethics, and governance related content. As a result, Sri Lankan accounting graduates develop both technical competence and professional judgment, enabling them to compete successfully in multinational corporations, international audit networks, and global financial institutions, both locally and overseas.

This progress reflects a broader national commitment to professional excellence. Accounting and finance are now recognised as disciplines central to economic governance, market transparency, investor confidence, and public trust.

Why Professional Qualifications Matter

Professional qualifications often act as gateways to the corporate world. Professional pathways in Sri Lanka include qualifications offered by the Institute of Chartered Accountants of Sri Lanka (ICASL), the Association of Chartered Certified Accountants (ACCA), the Chartered Institute of Management Accountants (CIMA), the Institute of Chartered Professional Managers (ICPM), and the Association of Accounting Technicians (AAT).

For employers, these qualifications signal technical competence, ethical compliance, and completion of structured practical training. For students, they represent professional legitimacy, career security, and upward mobility.

Therefore, families and students invest significant time and resources in this pathway, reflecting its importance, often exceeding the practical value of a degree alone. Qualified professionals trained through this system contribute to both Sri Lanka’s domestic financial sector and overseas markets.

The Growth and Public Role of the Audit Sector

Alongside educational development, Sri Lanka’s audit sector has expanded in scale and influence as businesses have become more complex and globally connected. Audit firms now operate across the listed companies.

Audit firms perform an important public interest function by assuring the credibility of financial information, supporting investor confidence, and underpinning regulatory compliance and corporate governance. Beyond service delivery, they also act as professional institutions that determine norms and train future leaders in accounting and finance.

As a result, internal practices within audit firms, including organisational culture, workload expectations, remuneration, and supervision, have implications that extend beyond individual workplaces, influencing professional judgment, audit quality, and long-term public trust.

The Dream of Becoming a Chartered Accountant

For thousands of young Sri Lankans, becoming a Chartered Accountant represents one of the most respected professional ambitions. It is widely viewed as a symbol of discipline, resilience, and upward mobility. Students enter the pathway with the expectation that years of study, sacrifice, and perseverance will ultimately lead to professional recognition and stability.

A defining feature of this pathway is mandatory practical training. To qualify, students must complete a prescribed period of supervised training, most commonly within audit firms. This requirement is designed to bridge theory and practice, ensuring that academic knowledge is reinforced through real world exposure, professional supervision, and ethical decision making.

In practice, securing a training position is often the most decisive and competitive stage of the journey. Without completing this training, the qualification remains unattainable regardless of examination success. Therefore, audit firms are not only employers but also essential gatekeepers to professional advancement, controlling access to qualifications, experience, and future career opportunities.

Where the System Begins to Strain

This structure, while well intentioned, creates a significant imbalance of power. Trainees depend on audit firms not only for income, but also for the completion of their professional qualification. In such circumstances, questioning workloads, working hours, or basic welfare provisions can feel risky. Many trainees remain silent, fearing that concerns could delay qualification or affect future career prospects.

Audit work is demanding worldwide, particularly during peak reporting periods. Long hours, tight deadlines, and intense fieldwork are widely recognised features of the profession. However, the concern arises when these pressures become normalised without sufficient regard for rest, safety, remuneration, or minimum working conditions.

Training allowances and entry-level remuneration in audit firms are often modest relative to workloads and expectations, with trainee allowances typically ranging from LKR 10,000 to 20,000 per month, despite daily working hours that frequently extend 8 to 12 hours. Many trainees accept low pay and long hours as temporary sacrifices in pursuit of long-term professional goals. Over time, when such conditions are justified as “part of training,” unhealthy practices risk becoming normalised and embedded within professional culture.

Such environments may still produce technically competent professionals, but at the cost of burnout, ethical fatigue, and reduced long term engagement with the profession.

A Regulatory Blind Spot

In Sri Lanka, audit firms are regulated by CA Sri Lanka with respect to professional standards, ethical conduct, examinations, and prescribed training requirements, thereby playing an important role in maintaining the profession’s credibility and international standing. This is a professional regulation.

However, professional regulation serves a different purpose from organisational or workplace oversight. While audit firms are subject to general labour laws, there is no audit specific public oversight mechanism that systematically reviews audit firms’ internal governance, remuneration structures, or training environments.

This creates a regulatory asymmetry. Audit firms scrutinise others under detailed regulatory frameworks, yet their own internal systems are not subject to equivalent public review. Given the large population of trainees with limited bargaining power, this gap may affect professional sustainability, audit quality, and public trust.

Following a recent tragedy involving a trainee, CA Sri Lanka issued a public condolence statement acknowledging stakeholder concerns and confirming that the circumstances are under review.

Looking Ahead

To strengthen the long-term sustainability of the audit profession, Sri Lanka may consider the following measures:

* Establish a dedicated public oversight body for audit firms, with responsibility for monitoring firm level governance, training environments, and organisational practices, complementing existing professional regulation.

* Introduce transparency reports for audit firms, requiring disclosure of governance structures, quality control systems, training arrangements, and continuing professional education practices.

* Apply modern labour governance principles, drawing on modern slavery frameworks used internationally that emphasise prevention, transparency, and early identification of labour related risks.

* Improve visibility of trainee remuneration and workload practices, particularly where mandatory training creates structural dependency.

* Strengthen coordination between professional self-regulation and public oversight, ensuring that professional excellence is supported by sustainable and accountable organisational environments.

These measures do not imply illegality or misconduct. Rather, they reflect an opportunity to align Sri Lanka’s audit profession with evolving global norms that prioritise transparency, dignity, and long-term public confidence. If audit firms are entrusted with holding others accountable, the systems governing them must also reflect responsibility toward the people who sustain the profession.

by Sulochana Dissanayake

Senior Lecturer at Rajarata University of Sri Lanka | Sessional Academic & PhD Candidate at Queensland University of Technology (QUT)

and

by Prof. Manoj Samarathunga

Faculty of Management Studies

Rajarata University of

Sri Lanka Mihintale

Opinion

Buddhist insights into the extended mind thesis – Some observations

It is both an honour and a pleasure to address you on this occasion as we gather to celebrate International Philosophy Day. Established by UNESCO and supported by the United Nations, this day serves as a global reminder that philosophy is not merely an academic discipline confined to universities or scholarly journals. It is, rather, a critical human practice—one that enables societies to reflect upon themselves, to question inherited assumptions, and to navigate periods of intellectual, technological, and moral transformation.

In moments of rapid change, philosophy performs a particularly vital role. It slows us down. It invites us to ask not only how things work, but what they mean, why they matter, and how we ought to live. I therefore wish to begin by expressing my appreciation to UNESCO, the United Nations, and the organisers of this year’s programme for sustaining this tradition and for selecting a theme that invites sustained reflection on mind, consciousness, and human agency.

We inhabit a world increasingly shaped by artificial intelligence, neuroscience, cognitive science, and digital technologies. These developments are not neutral. They reshape how we think, how we communicate, how we remember, and even how we imagine ourselves. As machines simulate cognitive functions once thought uniquely human, we are compelled to ask foundational philosophical questions anew:

What is the mind? Where does thinking occur? Is cognition something enclosed within the brain, or does it arise through our bodily engagement with the world? And what does it mean to be an ethical and responsible agent in a technologically extended environment?

Sri Lanka’s Philosophical Inheritance

On a day such as this, it is especially appropriate to recall that Sri Lanka possesses a long and distinguished tradition of philosophical reflection. From early Buddhist scholasticism to modern comparative philosophy, Sri Lankan thinkers have consistently engaged questions concerning knowledge, consciousness, suffering, agency, and liberation.

Within this modern intellectual history, the University of Peradeniya occupies a unique place. It has served as a centre where Buddhist philosophy, Western thought, psychology, and logic have met in creative dialogue. Scholars such as T. R. V. Murti, K. N. Jayatilleke, Padmasiri de Silva, R. D. Gunaratne, and Sarathchandra did not merely interpret Buddhist texts; they brought them into conversation with global philosophy, thereby enriching both traditions.

It is within this intellectual lineage—and with deep respect for it—that I offer the reflections that follow.

Setting the Philosophical Problem

My topic today is “Embodied Cognition and Viññāṇasota: Buddhist Insights on the Extended Mind Thesis – Some Observations.” This is not a purely historical inquiry. It is an attempt to bring Buddhist philosophy into dialogue with some of the most pressing debates in contemporary philosophy of mind and cognitive science.

At the centre of these debates lies a deceptively simple question: Where is the mind?

For much of modern philosophy, the dominant answer was clear: the mind resides inside the head. Thinking was understood as an internal process, private and hidden, occurring within the boundaries of the skull. The body was often treated as a mere vessel, and the world as an external stage upon which cognition operated.

However, this picture has increasingly come under pressure.

The Extended Mind Thesis and the 4E Turn

One of the most influential challenges to this internalist model is the Extended Mind Thesis, proposed by Andy Clark and David Chalmers. Their argument is provocative but deceptively simple: if an external tool performs the same functional role as a cognitive process inside the brain, then it should be considered part of the mind itself.

From this insight emerges the now well-known 4E framework, according to which cognition is:

Embodied – shaped by the structure and capacities of the body

Embedded – situated within physical, social, and cultural environments

Enactive – constituted through action and interaction

Extended – distributed across tools, artefacts, and practices

This framework invites us to rethink the mind not as a thing, but as an activity—something we do, rather than something we have.

Earlier Western Challenges to Internalism

It is important to note that this critique of the “mind in the head” model did not begin with cognitive science. It has deep philosophical roots.

Ludwig Wittgenstein

famously warned philosophers against imagining thought as something occurring in a hidden inner space. Such metaphors, he suggested, mystify rather than clarify our understanding of mind.

Similarly, Franz Brentano’s notion of intentionality—his claim that all mental states are about something—shifted attention away from inner substances toward relational processes. This insight shaped Husserl’s phenomenology, where consciousness is always world-directed, and Freud’s psychoanalysis, where mental life is dynamic, conflicted, and socially embedded.

Together, these thinkers prepared the conceptual ground for a more process-oriented, relational understanding of mind.

Varela and the Enactive Turn

A decisive moment in this shift came with Francisco J. Varela, whose work on enactivism challenged computational models of mind. For Varela, cognition is not the passive representation of a pre-given world, but the active bringing forth of meaning through embodied engagement.

Cognition, on this view, arises from the dynamic coupling of organism and environment. Importantly, Varela explicitly acknowledged his intellectual debt to Buddhist philosophy, particularly its insights into impermanence, non-self, and dependent origination.

Buddhist Philosophy and the Minding Process

Buddhist thought offers a remarkably sophisticated account of mind—one that is non-substantialist, relational, and processual. Across its diverse traditions, we find a consistent emphasis on mind as dependently arisen, embodied through the six sense bases, and shaped by intention and contact.

Crucially, Buddhism does not speak of a static “mind-entity”. Instead, it employs metaphors of streams, flows, and continuities, suggesting a dynamic process unfolding in relation to conditions.

Key Buddhist Concepts for Contemporary Dialogue

Let me now highlight several Buddhist concepts that are particularly relevant to contemporary discussions of embodied and extended cognition.

The notion of prapañca, as elaborated by Bhikkhu Ñāṇananda, captures the mind’s tendency toward conceptual proliferation. Through naming, interpretation, and narrative construction, the mind extends itself, creating entire experiential worlds. This is not merely a linguistic process; it is an existential one.

The Abhidhamma concept of viññāṇasota, the stream of consciousness, rejects the idea of an inner mental core. Consciousness arises and ceases moment by moment, dependent on conditions—much like a river that has no fixed identity apart from its flow.

The Yogācāra doctrine of ālayaviññāṇa adds a further dimension, recognising deep-seated dispositions, habits, and affective tendencies accumulated through experience. This anticipates modern discussions of implicit cognition, embodied memory, and learned behaviour.

Finally, the Buddhist distinction between mindful and unmindful cognition reveals a layered model of mental life—one that resonates strongly with contemporary dual-process theories.

A Buddhist Cognitive Ecology

Taken together, these insights point toward a Buddhist cognitive ecology in which mind is not an inner object but a relational activity unfolding across body, world, history, and practice.

As the Buddha famously observed, “In this fathom-long body, with its perceptions and thoughts, I declare there is the world.” This is perhaps one of the earliest and most profound articulations of an embodied, enacted, and extended conception of mind.

Conclusion

The Extended Mind Thesis challenges the idea that the mind is confined within the skull. Buddhist philosophy goes further. It invites us to reconsider whether the mind was ever “inside” to begin with.

In an age shaped by artificial intelligence, cognitive technologies, and digital environments, this question is not merely theoretical. It is ethically urgent. How we understand mind shapes how we design technologies, structure societies, and conceive human responsibility.

Buddhist philosophy offers not only conceptual clarity but also ethical guidance—reminding us that cognition is inseparable from suffering, intention, and liberation.

Dr. Charitha Herath is a former Member of Parliament of Sri Lanka (2020–2024) and an academic philosopher. Prior to entering Parliament, he served as Professor (Chair) of Philosophy at the University of Peradeniya. He was Chairman of the Committee on Public Enterprises (COPE) from 2020 to 2022, playing a key role in parliamentary oversight of public finance and state institutions. Dr. Herath previously served as Secretary to the Ministry of Mass Media and Information (2013–2015) and is the Founder and Chair of Nexus Research Group, a platform for interdisciplinary research, policy dialogue, and public intellectual engagement.

He holds a BA from the University of Peradeniya (Sri Lanka), MA degrees from Sichuan University (China) and Ohio University (USA), and a PhD from the University of Kelaniya (Sri Lanka).

(This article has been adapted from the keynote address delivered

by Dr. Charitha Herath

at the International Philosophy Day Conference at the University of Peradeniya.)

Opinion

We do not want to be press-ganged

Reference ,the Indian High Commissioner’s recent comments ( The Island, 9th Jan. ) on strong India-Sri Lanka relationship and the assistance granted on recovering from the financial collapse of Sri Lanka and yet again for cyclone recovery., Sri Lankans should express their thanks to India for standing up as a friendly neighbour.

On the Defence Cooperation agreement, the Indian High Commissioner’s assertion was that there was nothing beyond that which had been included in the text. But, dear High Commissioner, we Sri Lankans have burnt our fingers when we signed agreements with the European nations who invaded our country; they took our leaders around the Mulberry bush and made our nation pay a very high price by controlling our destiny for hundreds of years. When the Opposition parties in the Parliament requested the Sri Lankan government to reveal the contents of the Defence agreements signed with India as per the prevalent common practice, the government’s strange response was that India did not want them disclosed.

Even the terms of the one-sided infamous Indo-Sri Lanka agreement, signed in 1987, were disclosed to the public.

Mr. High Commissioner, we are not satisfied with your reply as we are weak, economically, and unable to clearly understand your “India’s Neighbourhood First and Mahasagar policies” . We need the details of the defence agreements signed with our government, early.

RANJITH SOYSA

-

Business1 day ago

Business1 day agoKoaloo.Fi and Stredge forge strategic partnership to offer businesses sustainable supply chain solutions

-

Business5 days ago

Business5 days agoDialog and UnionPay International Join Forces to Elevate Sri Lanka’s Digital Payment Landscape

-

News5 days ago

News5 days agoSajith: Ashoka Chakra replaces Dharmachakra in Buddhism textbook

-

Features5 days ago

Features5 days agoThe Paradox of Trump Power: Contested Authoritarian at Home, Uncontested Bully Abroad

-

Features5 days ago

Features5 days agoSubject:Whatever happened to (my) three million dollars?

-

Business1 day ago

Business1 day agoSLT MOBITEL and Fintelex empower farmers with the launch of Yaya Agro App

-

Business1 day ago

Business1 day agoHayleys Mobility unveils Premium Delivery Centre

-

News5 days ago

News5 days agoLevel I landslide early warnings issued to the Districts of Badulla, Kandy, Matale and Nuwara-Eliya extended