Features

Baurs’ coconut properties, early married life and Ceylon in the 40’s and 50’s

Excerpted from the authorized biography of Thilo Hoffmann by Douglas. B. Ranasinghe

(Continued from last week)

Mr Jobin (the Swiss superintendent) devoted most of his working life to Palugaswewa Estate and the people of the area. He established a fibre mill, produced large quantities of coconut shell charcoal, grew rice and introduced sheep rearing. The estate’s large herd of Mura water buffaloes yielded milk, curd and other products. Many thousands of selected coconut seedlings were raised and sold. Palugaswewa was the model of a modern and profitable coconut property, with much of the profits being ploughed back, until the takeover by the government.

Thilo and Mae often spent weekends here with the Jobins. ‘The property was then on the edge of the vast extent of dry zone jungle which stretched away northward and inland. He recalls the hot evenings when the hosts and guests would sit on the screened-in veranda of the Superintendent’s bungalow. Seasonally in the nearby large mara trees thousands of cicadas would fill the air with their peculiar ‘music’, coming in waves so loud that one could not hear oneself and conversation was almost impossible. A myriad fireflies illuminated the dark night. Packs of jackals would roam the area, and at night their wild howling was heard far and near. There were crocodiles in the surrounding tanks. Of course, there were mosquitoes.

Herds of elephants would move through the estate regularly, and often cause heavy damage especially to young palms and in new or replanted sections of it. The famous Deduru Oya herd, with its mystical connection to the Munesswaram temple, had its home range in the vicinity. This was until the herd was decimated in an attempt to trans-locate it to the Wilpattu National Park in the late 1960s, combined with the first immobilization experiments in Sri Lanka.

Thilo believes that the project was ill-conceived, and that the Wildlife Department organized it at the suggestion of a foreign wildlife movie-maker, who obtained dramatic footage. Sometime later several of the translocated animals returned to their home range, a distance of nearly 100 km.

In 1953 Baurs bought the mostly undeveloped Polontalawa Estate, at Kadigawa on the Deduru Oya some miles inland. This provided both Xavier and Thilo with many opportunities for wilderness adventures. It was here that Thilo’s friend Geoffrey Bawa with Ulrik Plesner later built a unique bungalow complex, its various units fitting among a group of large rocks and boulders with jungle trees between.

One Saturday evening in the 1950s Shirley Corea, the MP for Chilaw threw a party at the Sports Club grounds in the town. The Jobins and Thilo were invited. There was a large crowd, which included Bernard Soysa and Colvin R. de Silva.

Thilo was introduced to Colvin, and soon a friendly discussion took place between them about the merits of State ownership. Colvin asked him why he would not join and manage for the State a fertilizer business like Baurs, on terms and conditions equal to or better than those prevailing in the private sector. Thilo replied: “Because I would not be allowed to run it according to my best knowledge and ability; there would always be people to interfere.”

De Silva was apparently not convinced as, decades later, he used the same reasoning in connection with the State take-over of all agricultural lands of over 50 acres in extent (Land Reform), as the Minister in charge. Thilo recalls that a proprietary planter who thought he would play an important role in the scheme greeted the suggestion with enthusiasm only to find himself disillusioned in no time.

In later years Thilo tried to establish some new crop plants in Sri Lanka. Most successful was the macadamia nut. With difficulty he obtained a few dozen seeds from abroad and had them raised at the four up-country estates owned by Baurs. Then nationalisation intervened. Some years later the new Superintendent of Clarendon Estate sent him sample nuts from the first few harvests, and they were of good quality.

A fairly large trial was carried out with Hibiscus sabdariffa, the dried calyx of which is extensively used in herbal tea mixtures. Several hundredweights of it were exported. Thilo also experimented with soil-less culture and with minor element deficiencies.

MARRIAGE

After his early sojourn in the hill country, young Thilo Hoffmann returned to Colombo and lived in a bungalow belonging to Baurs named ‘Suramma’ at No. 14 Bagatelle Road. It had a large garden with a swimming pool, and in front stood a balsa tree, the ultra-light timber of which had been in great demand during the recent war for the construction of fighter planes. It was run as a chummery by young bachelors employed by Baurs. For one month in rotation each resident would be responsible for the household, supervise the servants and the kitchen, and do the marketing, as well as watch over the expenditure and income. This was a useful exercise for most of them.

At this time Thilo bought his first car, an MG TC, a brand new sports two-seater with a folding hood, bearing registration number CY 1406. He describes it as “hot and sticky” during rain but otherwise a joy to drive.

In late 1947 his fiancee, Mae Klauenbosch, came over from Switzerland. In England she boarded the Empire Brent, a converted passenger ship. She was in an inner cabin with 14 wives of European residents in India who came out to rejoin their husbands after the war. On the return trip to the UK these ships repatriated British soldiers. They were packed with people in both directions. Still, she enjoyed the voyage. Thilo recounts:

“At that time executives were not allowed to marry during the first contract of four years. I somehow managed to break this rule, which did not further endear me to the CEO. In the presence of a small crowd of friends and colleagues we were married by a registrar at the Grand Oriental Hotel.

“The ‘GOH’ then had a Swiss manager and a Swiss chef, and was much larger than today, comprising the entire building, now owned by the Bank of Ceylon. It was known all over the world because the Colombo port was a transit point for thousands of passengers travelling to and from Australia and ports in South East and East Asia. The ships had to stop here for bunkering, and they sailed on strict schedules. Almost all passengers came ashore and frequented the hotel.

“As was then the custom Mae stayed for about ten days, between arrival and wedding, with the family of the CEO of Baurs, who thus acted as substitute for her parents. She was introduced to the basic matters of life in Ceylon such as shopping and handling of servants.

“The newlyweds’ home was a small flat in Baurs building, which stood by the seashore in the Colombo Fort area, at Upper Chatham Street.”

Thilo was given one week off for the honeymoon. Their first stop was Kandy. In the evening they visited the Temple of the Tooth Relic and watched the puja. The next day they drove to Nuwara Eliya via Padiyapelella and Maturata. He recalls the railway line which connected Ragala via Nuwara Eliya to Nanu Oya, as they had to criss-cross its bumpy track between Brookside and Nuwara Eliya a number of times in their hard-sprung MG, an annoying experience. This railway, which today would have been a major tourist attraction, was removed a few years later.

They spent a day or two at Welimada, and then drove home via Bandarawela – Haputale – Koslanda – Wellawaya, with one night at the resthouse in Hambantota. This was then a small, romantic fishing town on the jungle-clad blue bay, with a population of mainly Malays and Burghers. The large ‘forest’ of palmyra palms on the dunes to the west was a special attraction of the place and a protection for it. It is now replaced by Casuarina trees, “alien and ugly” as Thilo says, planted by the Forest Department.

The couple returned home from their brief honeymoon to a room which had only a few pieces of furniture, by a then leading designer Terry Jonklaas. They had to unpack a new mattress and bed linen from Mae’s trunk before they were able to lie down for the night.

LIFE IN CEYLON

Colombo was then a beautiful and clean town, with numerous large gardens and trees. For instance, the Galle Road was entirely residential. Colombo was called the “Garden City” and Ceylon the “Switzerland of the East”. Since then, great changes have not only affected the rural areas of Sri Lanka, as noted often in this book, but, of course, the ever-growing towns, particularly the capital city.

The air was clean, and a myriad stars were visible in the night sky above the city.

Today a permanent haze blots out all but the most prominent of them. Vision throughout the country has become very restricted, with strong haze a normal feature. No longer is it possible to regularly see the southern sea coast from the Haputale area or Adam’s Peak from Colombo city. During his time in Sri Lanka Thilo could observe in the best viewing conditions three “fabulous” comets, namely Ikeya-Seki, Bennett and Kohoutek, a total eclipse of the sun and several of the moon.

There was no air conditioning in those days. Office papers on the desk got stuck to sweaty forearms. During the greatest heat in April and May the Hoffmanns used to drag their large double bed onto the open veranda and sleep in relative coolness under the stars or the moonlit sky. Thilo recalls:

“Our flat was on the fifth floor of Baur’s building. Lying on our stomachs looking over the edge of the veranda 50 feet above Flagstaff Street we used to watch in fascination the seasonal mass migration of butterflies, said to end at Sri Pada. From the ground up to our level millions of butterflies would flutter and fly northward for hours and days, rather like a cloud of large snowflakes. This happened at regular intervals for years, but later the migrations became fewer and the number of butterflies decreased greatly. I have not seen a real migration here for many years now.”

The crows of the whole area roosted at night in Crow Island off Mattakkuliya and their numbers were thus limited. This site is now no more. Today, as Thilo remarks, the population of crows in Colombo has increased out of all proportion, nesting and roosting all over the town, an unfailing indication of unsanitary conditions. They are now a pest and a menace to all other birds.

The Colombo Fort was the business and administrative centre of the country. All the big shops were there, too. There were impressive government buildings, many of which have, in the meantime, been demolished after falling into disrepair and decay. Only a few have been restored. From Baurs building, which stands at a prime location in the Fort, one had a fine view along the west coast as far as Mount Lavinia; this was blocked when the Hotel Intercontinental was built in the 1970s.

There was a wide space at Echelon Square, where now the country’s tallest buildings stand. Gordon Gardens was a public park, the breakwater a recreation area. All roads and buildings were well maintained. Thilo also notes:

“For a long time the tallest structure on the island was the Ceylinco Building at Queen’s Street (now Janadhipathi Mawatha). It was initiated by Senator Justin Kotelawala, who added a helicopter pad to set the height record. The plans for the building were purchased in the USA. But the local builders misread them and it stands with its back to the front. In 1996 it was severely damaged by the devastating LTTE bomb attack on the nearby Central Bank (which I witnessed and which also damaged Baur’s building). Some years later it was reconstructed and the original error corrected to some extent.

The Pettah was an attractive place with hundreds of shops, clean and well-organized roads, the old buildings pretty and colourful with country tiles on the roofs. Now, says Thilo, it is a mixture of mostly tasteless new buildings, and stalls on the pavements.

The city was also run differently, as he observes:

“Unlike today Colombo was subdivided politically and administratively into wards each of which had an elected member in the Municipal Council. The ward member was known to his voters and held personally responsible for the proper functioning of all amenities. Complaints were promptly looked into and rectified in a system far superior to the present anonymity.”

“There were no traffic jams anywhere in the country. Most people found driving a pleasure, even during the hottest season, as it was customary to have trees on both sides of all main roads. Driving on a trunk road in any direction from Colombo was like passing through a tunnel of massive rain trees (pare mara). Today, continues Thilo, only parts of Bauddhaloka Mawata (then Buller’s Road) and a few others in Colombo give an impression of how it was then throughout the country.”

There were tramways. One ran from the Fort through Pettah and Grandpas to Totalanga (just south of the Victoria Bridge) and another to Borella. Mae Hoffmann regularly used the first for shopping at the Pettah market, the fare being five cents one way.

The rupee, of course, had much greater value then. It was worth 1.30 Swiss francs; today one Swiss franc is worth well over 100 rupees. Thilo recalls:

“I had my haircut for one rupee plus a ten cent tip at the Lord Nelson Saloon on Chatham Street, which is still there. The cheapest local cigarette (‘Driving Girl’) cost 40 cents for a tin of 50, and an egg one cent.During the war as metals of all kinds were used to make arms none could be spared for coins, which were replaced by paper money, and even years after the war there were still small banknotes of 25 and 50 cent denominations.”

(To be continued)

Features

Pakistan-Sri Lanka ‘eye diplomacy’

Reminiscences:

I was appointed Managing Director of the Ceylon Petroleum Corporation (CPC) and Chairman of the Trincomalee Petroleum Terminals Ltd (TPTL – Indian Oil Company/ Petroleum Corporation of Sri Lanka joint venture), in February 2023, by President Ranil Wickremesinghe. I served as TPTL Chairman voluntarily. TPTL controls the world-renowned oil tank farm in Trincomalee, abandoned after World War II. Several programmes were launched to repair tanks and buildings there. I enjoyed travelling to Trincomalee, staying at Navy House and monitoring the progress of the projects. Trincomalee is a beautiful place where I spent most of my time during my naval career.

My main task as MD, CPC, was to ensure an uninterrupted supply of petroleum products to the public.

With the great initiative of the then CPC Chairman, young and energetic Uvis Mohammed, and equally capable CPC staff, we were able to do our job diligently, and all problems related to petroleum products were overcome. My team and I were able to ensure that enough stocks were always available for any contingency.

The CPC made huge profits when we imported crude oil and processed it at our only refinery in Sapugaskanda, which could produce more than 50,000 barrels of refined fuel in one stream working day! (One barrel is equal to 210 litres). This huge facility encompassing about 65 acres has more than 1,200 employees and 65 storage tanks.

A huge loss the CPC was incurring due to wrong calculation of “out turn loss” when importing crude oil by ships and pumping it through Single Point Mooring Buoy (SPMB) at sea and transferring it through underwater fuel transfer lines to service tanks was detected and corrected immediately. That helped increase the CPC’s profits.

By August 2023, the CPC made a net profit of 74,000 million rupees (74 billion rupees)! The President was happy, the government was happy, the CPC Management was happy and the hard-working CPC staff were happy. I became a Managing Director of a very happy and successful State-Owned Enterprise (SOE). That was my first experience in working outside military/Foreign service.

I will be failing in my duty if I do not mention Sagala Rathnayake, then Chief of Staff to the President, for recommending me for the post of MD, CPC.

The only grievance they had was that we were not able to pay their 2023 Sinhala/Tamil New Year bonus due to a government circular. After working at CPC for six months and steering it out of trouble, I was ready to move out of CPC.

I was offered a new job as the Sri Lanka High Commissioner to Pakistan. I was delighted and my wife and son were happy. Our association with Pakistan, especially with the Pakistan Military, is very long. My son started schooling in Karachi in 1995, when I was doing the Naval War Course there. My wife Yamuna has many good friends in Pakistan. I am the first Military officer to graduate from the Karachi University in 1996 (BSc Honours in War Studies) and have a long association with the Pakistan Navy and their Special Forces. I was awarded the Nishan-e-Imtiaz (Military) medal—the highest National award by the Pakistan Presidentm in 2019m when I was Chief of Defence Staff. I am the only Sri Lankan to have been awarded this prestigious medal so far. I knew my son and myself would be able to play a quiet game of golf every morning at the picturesque Margalla Golf Club, owned by the Pakistan Navy, at the foot of Margalla hills, at Islamabad. The golf club is just a walking distance from the High Commissioner’s residence.

When I took over as Sri Lanka High Commissioner at Islamabad on 06 December 2023, I realised that a number of former Service Commanders had held that position earlier. The first Ceylonese High Commissioner to Pakistan, with a military background, was the first Army Commander General Anton Muthukumaru. He was concurrently Ambassador to Iran. Then distinguished Service Commanders, like General H W G Wijayakoon, General Gerry Silva, General Srilal Weerasooriya, Air Chief Marshal Jayalath Weerakkody, served as High Commissioners to Islamabad. I took over from Vice Admiral Mohan Wijewickrama (former Chief of Staff of Navy and Governor Eastern Province).

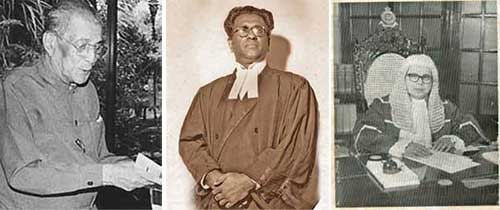

A photograph of Dr. Silva (second from right) in Brigadier

(Dr) Waquar Muzaffar’s album

One of the first visitors I received was Kawaja Hamza, a prominent Defence Correspondent in Islamabad. His request had nothing to do with Defence matters. He wanted to bring his 84-year-old father to see me; his father had his eyesight restored with corneas donated by a Sri Lankan in 1972! His eyesight is still good, but he did not know the Sri Lankan donor who gave him this most precious gift. He wanted to pay gratitude to the new Sri Lankan High Commissioner and to tell him that as a devoted Muslim, he prayed for the unknown donor every day! That reminded me of what my guru in Foreign Service, the late Foreign Minister Lakshman Kadirgamar told me when I was First Secretary/ Defence Advisor, Sri Lanka High Commission in New Delhi. That is “best diplomacy is people-to-people contacts.” This incident prompted me to research more into “Pakistan-Sri Lanka Eye Diplomacy” and what I learnt was fascinating!

Do you know the Sri Lanka Eye Donation Society has donated more than 26,000 corneas to Pakistan, since 1964 to date! That means more than 26,000 Pakistani people see the world with SRI LANKAN EYES! The Sri Lankan Eye Donation Society has provided 100,000 eye corneas to foreign countries FREE! To be exact 101,483 eye corneas during the last 65 years! More than one fourth of these donations was to one single country- Pakistan. Recent donations (in November 2024) were made to the Pakistan Military at Armed Forces Institute of Ophthalmology (AFIO), Rawalpindi, to restore the sight of Pakistan Army personnel who suffered eye injuries due to Improvised Explosive Devices (IED) blasts. This donation was done on the 75th Anniversary of the Sri Lanka Army.

Deshabandu Dr. F. G. Hudson Silva, a distinguished old boy of Nalanda College, Colombo, started collecting eye corneas as a medical student in 1958. His first set of corneas were collected from a deceased person and were stored at his home refrigerator at Wijerama Mawatha, Colombo 7. With his wife Iranganie De Silva (nee Kularatne), he started the Sri Lanka Eye Donation Society in 1961. They persuaded Buddhists to donate their eyes upon death. This drive was hugely successful.

Their son (now in the US) was a contemporary of mine at Royal College. I pledged to donate (of course with my parents’ permission) my eyes upon my death when I was a student at Royal college in 1972 on a Poson Full Moon Poya Day. Thousands have done so.

On Vesak Full Moon Poya Day in 1964, the first eye corneas were carried in a thermos flask filled with Ice, to Singapore, by Dr Hudson Silva and his wife and a successful eye transplant surgery was performed. From that day, our eye corneas were sent to 62 different countries.

Pakistan Lions Clubs, which supported this noble gesture, built a beautiful Eye Hospital for humble people at Gulberg, Lahore, where eye surgeries are performed, and named it Dr Hudson Silva Lions Eye Hospital.

The good work has continued even after the demise of Dr Hudson Silva in 1999.

So many people have donated their eyes upon their death, including President J. R. Jayewardene, whose eye corneas were used to restore the eyesight of one Japanese and one Sri Lankan. Dr Hudson Silva became a great hero in Pakistan and he was treated with dignity and respect whenever he visited Pakistan. My friend, Brigadier (Dr) Waquar Muzaffar, the Commandant of AFIO, was able to dig into his old photographs and send me a precious photo taken in 1980, 46 years ago (when he was a medical student), with Dr Hudson Silva.

We will remember Dr and Mrs Hudson Silva with gratitude.

Bravo Zulu to Sri Lanka Eye Donation Society!

by Admiral Ravindra C Wijegunaratne

by Admiral Ravindra C Wijegunaratne

WV, RWP and Bar, RSP, VSV, USP, NI (M) (Pakistan), ndc, psn, Bsc

(Hons) (War Studies) (Karachi) MPhil (Madras)

Former Navy Commander and Former Chief of Defense Staff

Former Chairman, Trincomalee Petroleum Terminals Ltd

Former Managing Director Ceylon Petroleum Corporation

Former High Commissioner to Pakistan

Features

Lasting solutions require consensus

Problems and solutions in plural societies like Sri Lanka’s which have deep rooted ethnic, religious and linguistic cleavages require a consciously inclusive approach. A major challenge for any government in Sri Lanka is to correctly identify the problems faced by different groups with strong identities and find solutions to them. The durability of democratic systems in divided societies depends less on electoral victories than on institutionalised inclusion, consultation, and negotiated compromise. When problems are defined only through the lens of a single political formation, even one that enjoys a large electoral mandate, such as obtained by the NPP government, the policy prescriptions derived from that diagnosis will likely overlook the experiences of communities that may remain outside the ruling party. The result could end up being resistance to those policies, uneven implementation and eventual political backlash.

A recent survey done by the National Peace Council (NPC), in Jaffna, in the North, at a focus group discussion for young people on citizen perception in the electoral process, revealed interesting developments. The results of the NPC micro survey support the findings of the national survey by Verite Research that found that government approval rating stood at 65 percent in early February 2026. A majority of the respondents in Jaffna affirm that they feel safer and more fairly treated than in the past. There is a clear improving trend to be seen in some areas, but not in all. This survey of predominantly young and educated respondents shows 78 percent saying livelihood has improved and an equal percentage feeling safe in daily life. 75 percent express satisfaction with the new government and 64 percent believe the state treats their language and culture fairly. These are not insignificant gains in a region that bore the brunt of three decades of war.

Yet the same survey reveals deep reservations that temper this optimism. Only 25 percent are satisfied with the handling of past issues. An equal percentage see no change in land and military related concerns. Most strikingly, almost 90 percent are worried about land being taken without consent for religious purposes. A significant number are uncertain whether the future will be better. These negative sentiments cannot be brushed aside as marginal. They point to unresolved structural questions relating to land rights, demilitarisation, accountability and the locus of political power. If these issues are not addressed sooner rather than later, the current stability may prove fragile. This suggests the need to build consensus with other parties to ensure long-term stability and legitimacy, and the need for partnership to address national issues.

NPP Absence

National or local level problems solving is unlikely to be successful in the longer term if it only proceeds from the thinking of one group of people even if they are the most enlightened. Problem solving requires the engagement of those from different ethno-religious, caste and political backgrounds to get a diversity of ideas and possible solutions. It does not mean getting corrupted or having to give up the good for the worse. It means testing ideas in the public sphere. Legitimacy flows not merely from winning elections but from the quality of public reasoning that precedes decision-making. The experience of successful post-conflict societies shows that long term peace and development are built through dialogue platforms where civil society organisations, political actors, business communities, and local representatives jointly define problems before negotiating policy responses.

As a civil society organisation, the National Peace Council engages in a variety of public activities that focus on awareness and relationship building across communities. Participants in those activities include community leaders, religious clergy, local level government officials and grassroots political party representatives. However, along with other civil society organisations, NPC has been finding it difficult to get the participation of members of the NPP at those events. The excuse given for the absence of ruling party members is that they are too busy as they are involved in a plenitude of activities. The question is whether the ruling party members have too much on their plate or whether it is due to a reluctance to work with others.

The general belief is that those from the ruling party need to get special permission from the party hierarchy for activities organised by groups not under their control. The reluctance of the ruling party to permit its members to join the activities of other organisations may be the concern that they will get ideas that are different from those held by the party leadership. The concern may be that these different ideas will either corrupt the ruling party members or cause dissent within the ranks of the ruling party. But lasting reform in a plural society requires precisely this exposure. If 90 percent of surveyed youth in Jaffna are worried about land issues, then engaging them, rather than shielding party representatives from uncomfortable conversations, is essential for accurate problem identification.

North Star

The Leader of the Lanka Sama Samaja Party (LSSP), Prof Tissa Vitarana, who passed away last week, gave the example for national level problem solving. As a government minister he took on the challenge the protracted ethnic conflict that led to three decades of war. He set his mind on the solution and engaged with all but never veered from his conviction about what the solution would be. This was the North Star to him, said his son to me at his funeral, the direction to which the Compass (Malimawa) pointed at all times. Prof Vitarana held the view that in a diverse and plural society there was a need to devolve power and share power in a structured way between the majority community and minority communities. His example illustrates that engagement does not require ideological capitulation. It requires clarity of purpose combined with openness to dialogue.

The ethnic and religious peace that prevails today owes much to the efforts of people like Prof Vitarana and other like-minded persons and groups which, for many years, engaged as underdogs with those who were more powerful. The commitment to equality of citizenship, non-racism, non-extremism and non-discrimination, upheld by the present government, comes from this foundation. But the NPC survey suggests that symbolic recognition and improved daily safety are not enough. Respondents prioritise personal safety, truth regarding missing persons, return of land, language use and reduction of military involvement. They are also asking for jobs after graduation, local economic opportunity, protection of property rights, and tangible improvements that allow them to remain in Jaffna rather than migrate.

If solutions are to be lasting they cannot be unilaterally imposed by one party on the others. Lasting solutions cannot be unilateral solutions. They must emerge from a shared diagnosis of the country’s deepest problems and from a willingness to address the negative sentiments that persist beneath the surface of cautious optimism. Only then can progress be secured against reversal and anchored in the consent of the wider polity. Engaging with the opposition can help mitigate the hyper-confrontational and divisive political culture of the past. This means that the ruling party needs to consider not only how to protect its existing members by cloistering them from those who think differently but also expand its vision and membership by convincing others to join them in problem solving at multiple levels. This requires engagement and not avoidance or withdrawal.

by Jehan Perera

Features

Unpacking public responses to educational reforms

As the debate on educational reforms rages, I find it useful to pay as much attention to the reactions they have excited as we do to the content of the reforms. Such reactions are a reflection of how education is understood in our society, and this understanding – along with the priorities it gives rise to – must necessarily be taken into account in education policy, including and especially reform. My aim in this piece, however, is to couple this public engagement with critical reflection on the historical-structural realities that structure our possibilities in the global market, and briefly discuss the role of academics in this endeavour.

As the debate on educational reforms rages, I find it useful to pay as much attention to the reactions they have excited as we do to the content of the reforms. Such reactions are a reflection of how education is understood in our society, and this understanding – along with the priorities it gives rise to – must necessarily be taken into account in education policy, including and especially reform. My aim in this piece, however, is to couple this public engagement with critical reflection on the historical-structural realities that structure our possibilities in the global market, and briefly discuss the role of academics in this endeavour.

Two broad reactions

The reactions to the proposed reforms can be broadly categorised into ‘pro’ and ‘anti’. I will discuss the latter first. Most of the backlash against the reforms seems to be directed at the issue of a gay dating site, accidentally being linked to the Grade 6 English module. While the importance of rigour cannot be overstated in such a process, the sheer volume of the energies concentrated on this is also indicative of how hopelessly homophobic our society is, especially its educators, including those in trade unions. These dispositions are a crucial part of the reason why educational reforms are needed in the first place. If only there was a fraction of the interest in ‘keeping up with the rest of the world’ in terms of IT, skills, and so on, in this area as well!

Then there is the opposition mounted by teachers’ trade unions and others about the process of the reforms not being very democratic, which I (and many others in higher education, as evidenced by a recent statement, available at https://island.lk/general-educational-reforms-to-what-purpose-a-statement-by-state-university-teachers/ ) fully agree with. But I earnestly hope the conversation is not usurped by those wanting to promote heteronormativity, further entrenching bigotry only education itself can save us from. With this important qualification, I, too, believe the government should open up the reform process to the public, rather than just ‘informing’ them of it.

It is unclear both as to why the process had to be behind closed doors, as well as why the government seems to be in a hurry to push the reforms through. Considering other recent developments, like the continued extension of emergency rule, tabling of the Protection of the State from Terrorism Act (PSTA), and proposing a new Authority for the protection of the Central Highlands (as is famously known, Authorities directly come under the Executive, and, therefore, further strengthen the Presidency; a reasonable question would be as to why the existing apparatus cannot be strengthened for this purpose), this appears especially suspect.

Further, according to the Secretary to the MOE Nalaka Kaluwewa: “The full framework for the [education] reforms was already in place [when the Dissanayake government took office]” (https://www.wsws.org/en/articles/2025/08/12/wxua-a12.html, citing The Morning, July 29). Given the ideological inclinations of the former Wickremesinghe government and the IMF negotiations taking place at the time, the continuation of education reforms, initiated in such a context with very little modification, leaves little doubt as to their intent: to facilitate the churning out of cheap labour for the global market (with very little cushioning from external shocks and reproducing global inequalities), while raising enough revenue in the process to service debt.

This process privileges STEM subjects, which are “considered to contribute to higher levels of ‘employability’ among their graduates … With their emphasis on transferable skills and demonstrable competency levels, STEM subjects provide tools that are well suited for the abstraction of labour required by capitalism, particularly at the global level where comparability across a wide array of labour markets matters more than ever before” (my own previous piece in this column on 29 October 2024). Humanities and Social Sciences (HSS) subjects are deprioritised as a result. However, the wisdom of an education policy that is solely focused on responding to the global market has been questioned in this column and elsewhere, both because the global market has no reason to prioritise our needs as well as because such an orientation comes at the cost of a strategy for improving the conditions within Sri Lanka, in all sectors. This is why we need a more emancipatory vision for education geared towards building a fairer society domestically where the fruits of prosperity are enjoyed by all.

The second broad reaction to the reforms is to earnestly embrace them. The reasons behind this need to be taken seriously, although it echoes the mantra of the global market. According to one parent participating in a protest against the halting of the reform process: “The world is moving forward with new inventions and technology, but here in Sri Lanka, our children are still burdened with outdated methods. Opposition politicians send their children to international schools or abroad, while ours depend on free education. Stopping these reforms is the lowest act I’ve seen as a mother” (https://www.newsfirst.lk/2026/01/17/pro-educational-reforms-protests-spread-across-sri-lanka). While it is worth mentioning that it is not only the opposition, nor in fact only politicians, who send their children to international schools and abroad, the point holds. Updating the curriculum to reflect the changing needs of a society will invariably strengthen the case for free education. However, as mentioned before, if not combined with a vision for harnessing education’s emancipatory potential for the country, such a move would simply translate into one of integrating Sri Lanka to the world market to produce cheap labour for the colonial and neocolonial masters.

According to another parent in a similar protest: “Our children were excited about lighter schoolbags and a better future. Now they are left in despair” (https://www.newsfirst.lk/2026/01/17/pro-educational-reforms-protests-spread-across-sri-lanka). Again, a valid concern, but one that seems to be completely buying into the rhetoric of the government. As many pieces in this column have already shown, even though the structure of assessments will shift from exam-heavy to more interim forms of assessment (which is very welcome), the number of modules/subjects will actually increase, pushing a greater, not lesser, workload on students.

A file photo of a satyagraha against education reforms

What kind of education?

The ‘pro’ reactions outlined above stem from valid concerns, and, therefore, need to be taken seriously. Relatedly, we have to keep in mind that opening the process up to public engagement will not necessarily result in some of the outcomes, those particularly in the HSS academic community, would like to see, such as increasing the HSS component in the syllabus, changing weightages assigned to such subjects, reintroducing them to the basket of mandatory subjects, etc., because of the increasing traction of STEM subjects as a surer way to lock in a good future income.

Academics do have a role to play here, though: 1) actively engage with various groups of people to understand their rationales behind supporting or opposing the reforms; 2) reflect on how such preferences are constituted, and what they in turn contribute towards constituting (including the global and local patterns of accumulation and structures of oppression they perpetuate); 3) bring these reflections back into further conversations, enabling a mutually conditioning exchange; 4) collectively work out a plan for reforming education based on the above, preferably in an arrangement that directly informs policy. A reform process informed by such a dialectical exchange, and a system of education based on the results of these reflections, will have greater substantive value while also responding to the changing times.

Two important prerequisites for this kind of endeavour to succeed are that first, academics participate, irrespective of whether they publicly endorsed this government or not, and second, that the government responds with humility and accountability, without denial and shifting the blame on to individuals. While we cannot help the second, we can start with the first.

Conclusion

For a government that came into power riding the wave of ‘system change’, it is perhaps more important than for any other government that these reforms are done for the right reasons, not to mention following the right methods (of consultation and deliberation). For instance, developing soft skills or incorporating vocational education to the curriculum could be done either in a way that reproduces Sri Lanka’s marginality in the global economic order (which is ‘system preservation’), or lays the groundwork to develop a workforce first and foremost for the country, limited as this approach may be. An inextricable concern is what is denoted by ‘the country’ here: a few affluent groups, a majority ethno-religious category, or everyone living here? How we define ‘the country’ will centrally influence how education policy (among others) will be formulated, just as much as the quality of education influences how we – students, teachers, parents, policymakers, bureaucrats, ‘experts’ – think about such categories. That is precisely why more thought should go to education policymaking than perhaps any other sector.

(Hasini Lecamwasam is attached to the Department of Political Science, University of Peradeniya).

Kuppi is a politics and pedagogy happening on the margins of the lecture hall that parodies, subverts, and simultaneously reaffirms social hierarchies.

-

Life style3 days ago

Life style3 days agoMarriot new GM Suranga

-

Business2 days ago

Business2 days agoMinistry of Brands to launch Sri Lanka’s first off-price retail destination

-

Features3 days ago

Features3 days agoMonks’ march, in America and Sri Lanka

-

Opinion6 days ago

Opinion6 days agoWill computers ever be intelligent?

-

Features3 days ago

Features3 days agoThe Rise of Takaichi

-

Features3 days ago

Features3 days agoWetlands of Sri Lanka:

-

News3 days ago

News3 days agoThailand to recruit 10,000 Lankans under new labour pact

-

News3 days ago

News3 days agoMassive Sangha confab to address alleged injustices against monks