Sat Mag

Bandula Nanayakkarawasam

“I was in Grade Four when Sunil Ariyaratne wrote ‘Sakura Mal Pipila’. That song first made me realise how abstract music could be. In later years, as he and Nanda Malini went on to endeavours like Sathyaye Geethaya and Pavana, I matured. Even now, when you listen to ‘Perahera Enawa’, you feel nothing but admiration for a man who rebelled against tradition and order in what he wrote.

By Uditha Devapriya

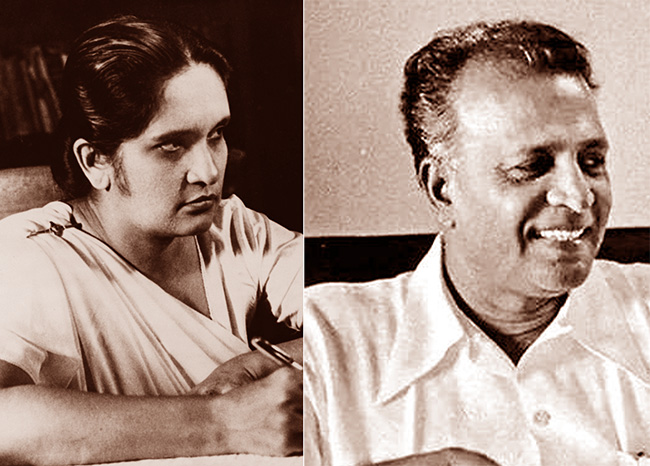

Tissa Abeysekara once called Bandula Nanayakkarawasam “the brightest spark in the fifth generation of contemporary Sinhala songwriters.” He didn’t name the five generations, but he did observe that their ancestry began with Ananda Samarakoon. With this we can try to chart the evolution of 20th century songwriters in terms of the singers who embodied those generations: Samarakoon, Sunil Shantha, Amaradeva, Victor Ratnayake, and T. M. Jayaratne, Sanath Nandasiri, and Neela Wickramasinghe among others.

By doing so we can also discern the cultural, social, and political impulses that distinguished each of these periods: Samarakoon by the gramophone Tower Hall culture; Shantha by the Hela Havula, led by its two chief heralds Munidasa Cumaratunga and Raphael Tennakoon; Amaradeva by the post-war generation of lyricists, Mahagama Sekara, Madawala S. Ratnayake, and Chandrarathna Manawasinghe being the definitive trio; Victor by the first post-1956 generation wave, epitomised by Premakeerthi de Alwis, K. D. K. Dharmawardena, Sunil Ariyaratne, and Ajantha Ranasinghe; and those who followed them among the second post-1956 generation, among them Bandula Nanayakkarawasam, Lucian Bulathsinghala, Buddhadasa Galappaththy, and the great Ratna Sri Wijesinghe. I see Jackson Anthony has described Nanayakkarawasam as the last of his kind. If he’s not quite the last of his kind, he’s certainly the last anyone will be able to equal.

It’s important to locate Nanayakkarawasam in the wider social and cultural landscape of the country. The generation who followed the likes of Sunil Ariyaratne and Ajantha Ranasinghe were witnesses to some of the most widely felt changes in the economy: the adoption of free market policies, the privatisation of the cinema that democratised cultural tastes and standards, and the introduction of television that would eventually cripple the theatre and cinema. While earlier generations had found employment in the universities (Ariyaratne) and journalism (Ranasinghe), the new artistes, by dint of these vast changes, were compelled to seek refuge in the private sector; the State could no longer insure them against the vagaries of the economy. In this context, Nanayakkarawasam would take the occasional leave from his bank, come to Colombo, and record his show aboard the SLBC.

In fact, most of these artistes, working from nine to five, had to prioritise their employment over their artistic pursuits. Nanayakkarawasam was no exception. Palitha Perera, reflecting on his days in the SLBC, remembers trying to get the man “to do his own programmes in Colombo” and failing to entice him to leave his fulltime job at the bank.

The biggest irony was when Madawala S. Ratnayake decided to take Nanayakkarawasam to his programme Yawwana Samajaya; as with other attempts, this too failed to get the man to leave his banking career. For Palitha though, it was more a fortunate coincidence than a missed opportunity: “Given what happened to the SLBC later on, it was Bandula’s luck that he didn’t end up wasting away here.” I’m sure that Bandula, being the self-effacing man he is, would disagree, but I am convinced, given the plight the likes of Palitha fell into in later years, that it was his luck which kept him away.

Nanayakkarawasam was born in Galle, around two or three kilometres from town. His childhood was, in his own words, quite fortunate in terms of the education he received. His first encounter with music had been a large Mullard radio bought by his uncle, a connoisseur of the arts who had apparently been a collector of rare items and instruments. “Since we lived at a time when not even the richest families from our neighbourhood owned a radio, big or small, owning a Mullard was certainly a big deal.”

The contraption had entranced young Bandula in more ways than one. “Back then we had just two local services run by one station, Radio Ceylon. It was on this radio that I first ‘obtained’ an education in music. I was also the youngest in my family by a wide margin, my podi akka being eight years older than me. Naturally, I was a bit of a loner in my house, and in my free time, which I never lacked even when I was at school, I used to place my ears on it and listen to songs.” He jokingly tells me that he once believed that the singers and announcers who sang and spoke were hidden in that device: “So when I listened to it during a thunderstorm and loku akka warned me that when lightning struck it would break apart, I honestly believed her. At the time I would have been five.”

I ask him whether he looked for the lyrics in a song. “Not really. We first hear a tune, then a voice, then a name. It was in my time that people like Victor Ratnayake and Sanath Nandasiri emerged. Amaradeva came before them. As a child I went for Victor’s songs because of his voice.” I put to him that the likes of Victor emerged as a result of the efforts Amaradeva made. “Yes. It was thanks to Victor that we realised how poetic Amaradeva’s lyrics were. But poetry didn’t figure highly in me then.”

His interest in the arts developed beyond music. His father, a firm leftist and an avid reader, would give him as much as 100 rupees to buy books. “I used to go to a store owned by a man called Lionel and purchase as much as I could, because back then a book cost four rupees.” He would get hooked on to Russian literature, which he says made him see the world in a different light, even through translation. “We had novels, short story collections, and poetry published by Progress Publishers. I indulged in them all.”

Young Bandula was sent to Richmond College, where his teachers inculcated in him a wider appreciation of what he’d grown to love. “One of my English teachers was a man called W. S. Bandara. He introduced me to the English translations of Chekhov, Gogol, Dostoyevsky, and Turgenev. It was then that I realised how woefully inadequate our translators were. Of course there were exceptions like K. G. Karunathilaka, but barring them the others didn’t feel the text they were working on.”

Apparently the radio figured so much in his life that he couldn’t really do without it even when studying. “A man called Jinasena lent me some flexible wires, which I then used on an American speaker which belonged to my uncle. Our house overlooked a wel yaya. When I listened to the radio in my room while studying Arithmetic, that wel yaya was always in my sight. That was the kind of childhood and education I had.” As he grew up though, it wasn’t just songs that he listened to but other programmes too: E. W. Adikaram’s Vidya Dahanaya, Mahinda Ranaweera’s Sithijaya, Lucien Bulathsinghala’s Sandella, H. M. Gunasekera’s Irida Sangrahaya, and Tissa Abeysekara’s Art Magazine. It should be mentioned that Bandula got to host Irida Sangrahaya in the 1980s, “a happy coincidence given that my father, who grew up listening to Gunasekara with me, was now listening to his son presenting it.”

Curious as to what his tastes were, I then ask whether he differentiated between “low” and “high” art. “That came later. But back then we read and we exchanged newspapers with our neighbours.

So we weren’t completely ignorant of this divide between ‘high’ and ‘low’ art. For instance, I came across Jayawilal Wilegoda’s articles on the cinema. Wilegoda lambasted Sinhala films that imitated Bollywood. People like him were asking questions like how a popular verse like ‘jeevithaye kanthare thurunu wiyali walle uthura gala yayi adare’ made sense, when they didn’t. By the time we grew up and passed adolescence, we knew about this divide. The important thing is it didn’t intimidate us.”

Bandula’s reference to films isn’t arbitrary: even the cinema had entranced him. To put all his encounters here would be impossible, though. Suffice it to say that he entertained the idea of being a scriptwriter at one point, even getting into the Sri Lanka Television Training Institute (or SLTTI) along with Sumitra Rahubadda, K. B. Herath, and Douglas Siriwardena. “I was taught by Tissa Abeysekara.” Notwithstanding his stints at the SLTTI, though, he didn’t get to become a full time scriptwriter until later, with a TV adaptation of T. B. Ilangaratne’s Vilambita, directed by Lakshman Wijesekara and telecast on Swarnavahini.

He gets back to his musical career. “I was in Grade Four when Sunil Ariyaratne wrote ‘Sakura Mal Pipila’. That song first made me realise how abstract music could be. In later years, as he and Nanda Malini went on to endeavours like Sathyaye Geethaya and Pavana, I matured. Even now, when you listen to ‘Perahera Enawa’, you feel nothing but admiration for a man who rebelled against tradition and order in what he wrote. The two of them taught me about the potential of a song. I can’t write about the things they explored with such vigour, but that doesn’t take away my admiration for them.”

It was under these circumstances that Nanayakkarawasam began what would become a very popular programme , in 2011. Rae Ira Pana picked up audiences so fast it defied the findings of the ratings agencies, which consistently demeaned it. Having shifted from one channel to another, it ended “for good” in 2015 and transformed into its own live show on March 10, 2017 at Nelum Pokuna, followed by a second show in November at the Polgolla Mahinda Rajapaksa Auditorium; two years later, on March 10, Bandula hosted a third show at the Karapitiya Auditorium in Galle, and on October 12 that year he organised a fourth at the BMICH. Nanayakkarawasam found in them all an ideal opportunity to do what he did from his days at the SLBC in the 1980s: tell us the story behind an objet d’art.

How viral did it become exactly? “People would come up to me showing me their pen drives and saying that they had recorded every, or every other, Rae Ira Pana show since 2011. I was just dumbfounded, because the ratings didn’t show it as a popular programme at all. I knew then that such agency findings, while scientific and verifiable, were in no way a measure of actual popularity outside the numbers. When it was jettisoned from one radio station after another, and when it evolved into its own live event, I came to realise it could be used to bring people together for worthy causes.”

What about now? According to Bandula, the Sinhala lyric is progressively deteriorating in quality. I ask him whether this is because our generation isn’t as receptive to the abstract in art as his had been. He tells me he doesn’t think so. “We’ve commercialised music, which isn’t necessarily a bad thing, but we’re confused about what a popular song is. When was the last time you heard a meaningful bus sinduwa?”

I suggest here that things would certainly have been better in his time, but he agrees only half heartedly. “You suggested earlier that we’ve de-sensitised ourselves so much that we can’t appreciate art. This isn’t something new. In my day, to give you an example, there was a vocalist called Piyasiri Wijeratne. He isn’t remembered today because he wasn’t a very prodigious artiste. In later years, Tissa Abeysekara would observe that Piyasiri possessed one of the best voices in this country. But did we recognise him then? No.”

I see his point. Blaming some imaginary malaise for the “cultural desert” we seem to find ourselves stranded in today blinds us, to an extent at least, to the fact that in each and every epoch our music “industry” has faced a huge deficit.

Besides, and this is putting it mildly, I don’t hear Nanayakkarawasam much on the bus.

That should tell us something.

The writer can be reached at udakdev1@gmail.com

Sat Mag

October 13 at the Women’s T20 World Cup: Injury concerns for Australia ahead of blockbuster game vs India

Australia vs India

Sharjah, 6pm local time

Australia have major injury concerns heading into the crucial clash. Just four balls into the match against Pakistan, Tayla Vlaeminck was out with a right shoulder dislocation. To make things worse, captain Alyssa Healy suffered an acute right foot injury while batting on 37 as she hobbled off the field with Australia needing 14 runs to win. Both players went for scans on Saturday.

India captain Harmanpreet Kaur who had hurt her neck in the match against Pakistan, turned up with a pain-relief patch on the right side of her neck during the Sri Lanka match. She also didn’t take the field during the chase. Fast bowler Pooja Vastrakar bowled full-tilt before the Sri Lanka game but didn’t play.

India will want a big win against Australia. If they win by more than 61 runs, they will move ahead of Australia, thereby automatically qualifying for the semi-final. In a case where India win by fewer than 60 runs, they will hope New Zealand win by a very small margin against Pakistan on Monday. For instance, if India make 150 against Australia and win by exactly 10 runs, New Zealand need to beat Pakistan by 28 runs defending 150 to go ahead of India’s NRR. If India lose to Australia by more than 17 runs while chasing a target of 151, then New Zealand’s NRR will be ahead of India, even if Pakistan beat New Zealand by just 1 run while defending 150.

Overall, India have won just eight out of 34 T20Is they’ve played against Australia. Two of those wins came in the group-stage games of previous T20 World Cups, in 2018 and 2020.

Australia squad:

Alyssa Healy (capt & wk), Darcie Brown, Ashleigh Gardner, Kim Garth, Grace Harris, Alana King, Phoebe Litchfield, Tahlia McGrath, Sophie Molineux, Beth Mooney, Ellyse Perry, Megan Schutt, Annabel Sutherland, Tayla Vlaeminck, Georgia Wareham

India squad:

Harmanpreet Kaur (capt), Smriti Mandhana (vice-capt), Yastika Bhatia (wk), Shafali Verma, Deepti Sharma, Jemimah Rodrigues, Richa Ghosh (wk), Pooja Vastrakar, Arundhati Reddy, Renuka Singh, D Hemalatha, Asha Sobhana, Radha Yadav, Shreyanka Patil, S Sajana

Tournament form guide:

Australia have three wins in three matches and are coming into this contest having comprehensively beaten Pakistan. With that win, they also all but sealed a semi-final spot thanks to their net run rate of 2.786. India have two wins in three games. In their previous match, they posted the highest total of the tournament so far – 172 for 3 and in return bundled Sri Lanka out for 90 to post their biggest win by runs at the T20 World Cup.

Players to watch:

Two of their best batters finding their form bodes well for India heading into the big game. Harmanpreet and Mandhana’s collaborative effort against Pakistan boosted India’s NRR with the semi-final race heating up. Mandhana, after a cautious start to her innings, changed gears and took on Sri Lanka’s spinners to make 50 off 38 balls. Harmanpreet, continuing from where she’d left against Pakistan, played a classic, hitting eight fours and a six on her way to a 27-ball 52. It was just what India needed to reinvigorate their T20 World Cup campaign.

[Cricinfo]

Sat Mag

Living building challenge

By Eng. Thushara Dissanayake

The primitive man lived in caves to get shelter from the weather. With the progression of human civilization, people wanted more sophisticated buildings to fulfill many other needs and were able to accomplish them with the help of advanced technologies. Security, privacy, storage, and living with comfort are the common requirements people expect today from residential buildings. In addition, different types of buildings are designed and constructed as public, commercial, industrial, and even cultural or religious with many advanced features and facilities to suit different requirements.

We are facing many environmental challenges today. The most severe of those is global warming which results in many negative impacts, like floods, droughts, strong winds, heatwaves, and sea level rise due to the melting of glaciers. We are experiencing many of those in addition to some local issues like environmental pollution. According to estimates buildings account for nearly 40% of all greenhouse gas emissions. In light of these issues, we have two options; we change or wait till the change comes to us. Waiting till the change come to us means that we do not care about our environment and as a result we would have to face disastrous consequences. Then how can we change in terms of building construction?

Before the green concept and green building practices come into play majority of buildings in Sri Lanka were designed and constructed just focusing on their intended functional requirements. Hence, it was much likely that the whole process of design, construction, and operation could have gone against nature unless done following specific regulations that would minimize negative environmental effects.

We can no longer proceed with the way we design our buildings which consumes a huge amount of material and non-renewable energy. We are very concerned about the food we eat and the things we consume. But we are not worrying about what is a building made of. If buildings are to become a part of our environment we have to design, build and operate them based on the same principles that govern the natural world. Eventually, it is not about the existence of the buildings, it is about us. In other words, our buildings should be a part of our natural environment.

The living building challenge is a remarkable design philosophy developed by American architect Jason F. McLennan the founder of the International Living Future Institute (ILFI). The International Living Future Institute is an environmental NGO committed to catalyzing the transformation toward communities that are socially just, culturally rich, and ecologically restorative. Accordingly, a living building must meet seven strict requirements, rather certifications, which are called the seven “petals” of the living building. They are Place, Water, Energy, Equity, Materials, Beauty, and Health & Happiness. Presently there are about 390 projects around the world that are being implemented according to Living Building certification guidelines. Let us see what these seven petals are.

Place

This is mainly about using the location wisely. Ample space is allocated to grow food. The location is easily accessible for pedestrians and those who use bicycles. The building maintains a healthy relationship with nature. The objective is to move away from commercial developments to eco-friendly developments where people can interact with nature.

Water

It is recommended to use potable water wisely, and manage stormwater and drainage. Hence, all the water needs are captured from precipitation or within the same system, where grey and black waters are purified on-site and reused.

Energy

Living buildings are energy efficient and produce renewable energy. They operate in a pollution-free manner without carbon emissions. They rely only on solar energy or any other renewable energy and hence there will be no energy bills.

Equity

What if a building can adhere to social values like equity and inclusiveness benefiting a wider community? Yes indeed, living buildings serve that end as well. The property blocks neither fresh air nor sunlight to other adjacent properties. In addition, the building does not block any natural water path and emits nothing harmful to its neighbors. On the human scale, the equity petal recognizes that developments should foster an equitable community regardless of an individual’s background, age, class, race, gender, or sexual orientation.

Materials

Materials are used without harming their sustainability. They are non-toxic and waste is minimized during the construction process. The hazardous materials traditionally used in building components like asbestos, PVC, cadmium, lead, mercury, and many others are avoided. In general, the living buildings will not consist of materials that could negatively impact human or ecological health.

Beauty

Our physical environments are not that friendly to us and sometimes seem to be inhumane. In contrast, a living building is biophilic (inspired by nature) with aesthetical designs that beautify the surrounding neighborhood. The beauty of nature is used to motivate people to protect and care for our environment by connecting people and nature.

Health & Happiness

The building has a good indoor and outdoor connection. It promotes the occupants’ physical and psychological health while causing no harm to the health issues of its neighbors. It consists of inviting stairways and is equipped with operable windows that provide ample natural daylight and ventilation. Indoor air quality is maintained at a satisfactory level and kitchen, bathrooms, and janitorial areas are provided with exhaust systems. Further, mechanisms placed in entrances prevent any materials carried inside from shoes.

The Bullitt Center building

Bullitt Center located in the middle of Seattle in the USA, is renowned as the world’s greenest commercial building and the first office building to earn Living Building certification. It is a six-story building with an area of 50,000 square feet. The area existed as a forest before the city was built. Hence, the Bullitt Center building has been designed to mimic the functions of a forest.

The energy needs of the building are purely powered by the solar system on the rooftop. Even though Seattle is relatively a cloudy city the Bullitt Center has been able to produce more energy than it needed becoming one of the “net positive” solar energy buildings in the world. The important point is that if a building is energy efficient only the area of the roof is sufficient to generate solar power to meet its energy requirement.

It is equipped with an automated window system that is able to control the inside temperature according to external weather conditions. In addition, a geothermal heat exchange system is available as the source of heating and cooling for the building. Heat pumps convey heat stored in the ground to warm the building in the winter. Similarly, heat from the building is conveyed into the ground during the summer.

The potable water needs of the building are achieved by treating rainwater. The grey water produced from the building is treated and re-used to feed rooftop gardens on the third floor. The black water doesn’t need a sewer connection as it is treated to a desirable level and sent to a nearby wetland while human biosolid is diverted to a composting system. Further, nearly two third of the rainwater collected from the roof is fed into the groundwater and the process resembles the hydrologic function of a forest.

It is encouraging to see that most of our large-scale buildings are designed and constructed incorporating green building concepts, which are mainly based on environmental sustainability. The living building challenge can be considered an extension of the green building concept. Amanda Sturgeon, the former CEO of the ILFI, has this to say in this regard. “Before we start a project trying to cram in every sustainable solution, why not take a step outside and just ask the question; what would nature do”?

Sat Mag

Something of a revolution: The LSSP’s “Great Betrayal” in retrospect

By Uditha Devapriya

On June 7, 1964, the Central Committee of the Lanka Sama Samaja Party convened a special conference at which three resolutions were presented. The first, moved by N. M. Perera, called for a coalition with the SLFP, inclusive of any ministerial portfolios. The second, led by the likes of Colvin R. de Silva, Leslie Goonewardena, and Bernard Soysa, advocated a line of critical support for the SLFP, but without entering into a coalition. The third, supported by the likes of Edmund Samarakkody and Bala Tampoe, rejected any form of compromise with the SLFP and argued that the LSSP should remain an independent party.

The conference was held a year after three parties – the LSSP, the Communist Party, and Philip Gunawardena’s Mahajana Eksath Peramuna – had founded a United Left Front. The ULF’s formation came in the wake of a spate of strikes against the Sirimavo Bandaranaike government. The previous year, the Ceylon Transport Board had waged a 17-day strike, and the harbour unions a 60-day strike. In 1963 a group of working-class organisations, calling itself the Joint Committee of Trade Unions, began mobilising itself. It soon came up with a common programme, and presented a list of 21 radical demands.

In response to these demands, Bandaranaike eventually supported a coalition arrangement with the left. In this she was opposed, not merely by the right-wing of her party, led by C. P. de Silva, but also those in left parties opposed to such an agreement, including Bala Tampoe and Edmund Samarakkody. Until then these parties had never seen the SLFP as a force to reckon with: Leslie Goonewardena, for instance, had characterised it as “a Centre Party with a programme of moderate reforms”, while Colvin R. de Silva had described it as “capitalist”, no different to the UNP and by default as bourgeois as the latter.

The LSSP’s decision to partner with the government had a great deal to do with its changing opinions about the SLFP. This, in turn, was influenced by developments abroad. In 1944, the Fourth International, which the LSSP had affiliated itself with in 1940 following its split with the Stalinist faction, appointed Michel Pablo as its International Secretary. After the end of the war, Pablo oversaw a shift in the Fourth International’s attitude to the Soviet states in Eastern Europe. More controversially, he began advocating a strategy of cooperation with mass organisations, regardless of their working-class or radical credentials.

Pablo argued that from an objective perspective, tensions between the US and the Soviet Union would lead to a “global civil war”, in which the Soviet Union would serve as a midwife for world socialist revolution. In such a situation the Fourth International would have to take sides. Here he advocated a strategy of entryism vis-à-vis Stalinist parties: since the conflict was between Stalinist and capitalist regimes, he reasoned, it made sense to see the former as allies. Such a strategy would, in his opinion, lead to “integration” into a mass movement, enabling the latter to rise to the level of a revolutionary movement.

Though controversial, Pablo’s line is best seen in the context of his times. The resurgence of capitalism after the war, and the boom in commodity prices, had a profound impact on the course of socialist politics in the Third World. The stunted nature of the bourgeoisie in these societies had forced left parties to look for alternatives. For a while, Trotsky had been their guide: in colonial and semi-colonial societies, he had noted, only the working class could be expected to see through a revolution. This entailed the establishment of workers’ states, but only those arising from a proletarian revolution: a proposition which, logically, excluded any compromise with non-radical “alternatives” to the bourgeoisie.

To be sure, the Pabloites did not waver in their support for workers’ states. However, they questioned whether such states could arise only from a proletarian revolution. For obvious reasons, their reasoning had great relevance for Trotskyite parties in the Third World. The LSSP’s response to them showed this well: while rejecting any alliance with Stalinist parties, the LSSP sympathised with the Pabloites’ advocacy of entryism, which involved a strategic orientation towards “reformist politics.” For the world’s oldest Trotskyite party, then going through a series of convulsions, ruptures, and splits, the prospect of entering the reformist path without abandoning its radical roots proved to be welcoming.

Writing in the left-wing journal Community in 1962, Hector Abhayavardhana noted some of the key concerns that the party had tried to resolve upon its formation. Abhayavardhana traced the LSSP’s origins to three developments: international communism, the freedom struggle in India, and local imperatives. The latter had dictated the LSSP’s manifesto in 1936, which included such demands as free school books and the use of Sinhala and Tamil in the law courts. Abhayavardhana suggested, correctly, that once these imperatives changed, so would the party’s focus, though within a revolutionary framework. These changes would be contingent on two important factors: the establishment of universal franchise in 1931, and the transfer of power to the local bourgeoisie in 1948.

Paradoxical as it may seem, the LSSP had entered the arena of radical politics through the ballot box. While leading the struggle outside parliament, it waged a struggle inside it also. This dual strategy collapsed when the colonial government proscribed the party and the D. S. Senanayake government disenfranchised plantation Tamils. Suffering two defeats in a row, the LSSP was forced to think of alternatives. That meant rethinking categories such as class, and grounding them in the concrete realities of the country.

This was more or less informed by the irrelevance of classical and orthodox Marxian analysis to the situation in Sri Lanka, specifically to its rural society: with a “vast amorphous mass of village inhabitants”, Abhayavardhana observed, there was no real basis in the country for a struggle “between rich owners and the rural poor.” To complicate matters further, reforms like the franchise and free education, which had aimed at the emancipation of the poor, had in fact driven them away from “revolutionary inclinations.” The result was the flowering of a powerful rural middle-class, which the LSSP, to its discomfort, found it could not mobilise as much as it had the urban workers and plantation Tamils.

Where else could the left turn to? The obvious answer was the rural peasantry. But the rural peasantry was in itself incapable of revolution, as Hector Abhayavardhana has noted only too clearly. While opposing the UNP’s Westernised veneer, it did not necessarily oppose the UNP’s overtures to Sinhalese nationalism. As historians like K. M. de Silva have observed, the leaders of the UNP did not see their Westernised ethos as an impediment to obtaining support from the rural masses. That, in part at least, was what motivated the Senanayake government to deprive Indian estate workers of their most fundamental rights, despite the existence of pro-minority legal safeguards in the Soulbury Constitution.

To say this is not to overlook the unique character of the Sri Lankan rural peasantry and petty bourgeoisie. Orthodox Marxists, not unjustifiably, characterise the latter as socially and politically conservative, tilting more often than not to the right. In Sri Lanka, this has frequently been the case: they voted for the UNP in 1948 and 1952, and voted en masse against the SLFP in 1977. Yet during these years they also tilted to the left, if not the centre-left: it was the petty bourgeoisie, after all, which rallied around the SLFP, and supported its more important reforms, such as the nationalisation of transport services.

One must, of course, be wary of pasting the radical tag on these measures and the classes that ostensibly stood for them. But if the Trotskyite critique of the bourgeoisie – that they were incapable of reform, even less revolution – holds valid, which it does, then the left in the former colonies of the Third World had no alternative but to look elsewhere and to be, as Abhayavardhana noted, “practical men” with regard to electoral politics. The limits within which they had to work in Sri Lanka meant that, in the face of changing dynamics, especially among the country’s middle-classes, they had to change their tactics too.

Meanwhile, in 1953, the Trotskyite critique of Pabloism culminated with the publication of an Open Letter by James Cannon, of the US Socialist Workers’ Party. Cannon criticised the Pabloite line, arguing that it advocated a policy of “complete submission.” The publication of the letter led to the withdrawal of the International Committee of the Fourth International from the International Secretariat. The latter, led by Pablo, continued to influence socialist parties in the Third World, advocating temporary alliances with petty bourgeois and centrist formations in the guise of opposing capitalist governments.

For the LSSP, this was a much-needed opening. Even as late as 1954, three years after S. W. R. D. Bandaranaike formed the SLFP, the LSSP continued to characterise the latter as the alternative bourgeois party in Ceylon. Yet this did not deter it from striking up no contest pacts with Bandaranaike at the 1956 election, a strategy that went back to November 1951, when the party requested the SLFP to hold a discussion about the possibility of eliminating contests in the following year’s elections. Though it extended critical support to the MEP government in 1956, the LSSP opposed the latter once it enacted emergency measures in 1957, mobilising trade union action for a period of three years.

At the 1960 election the LSSP contested separately, with the slogan “N. M. for P.M.” Though Sinhala nationalism no longer held sway as it had in 1956, the LSSP found itself reduced to a paltry 10 seats. It was against this backdrop that it began rethinking its strategy vis-à-vis the ruling party. At the throne speech in April 1960, Perera openly declared that his party would not stabilise the SLFP. But a month later, in May, he called a special conference, where he moved a resolution for a coalition with the party. As T. Perera has noted in his biography of Edmund Samarakkody, the response to the resolution unearthed two tendencies within the oppositionist camp: the “hardliners” who opposed any compromise with the SLFP, including Samarakkody, and the “waverers”, including Leslie Goonewardena.

These tendencies expressed themselves more clearly at the 1964 conference. While the first resolution by Perera called for a complete coalition, inclusive of Ministries, and the second rejected a coalition while extending critical support, the third rejected both tactics. The outcome of the conference showed which way these tendencies had blown since they first manifested four years earlier: Perera’s resolution obtained more than 500 votes, the second 75 votes, the third 25. What the anti-coalitionists saw as the “Great Betrayal” of the LSSP began here: in a volte-face from its earlier position, the LSSP now held the SLFP as a party of a radical petty bourgeoisie, capable of reform.

History has not been kind to the LSSP’s decision. From 1970 to 1977, a period of less than a decade, these strategies enabled it, as well as the Communist Party, to obtain a number of Ministries, as partners of a petty bourgeois establishment. This arrangement collapsed the moment the SLFP turned to the right and expelled the left from its ranks in 1975, in a move which culminated with the SLFP’s own dissolution two years later.

As the likes of Samarakkody and Meryl Fernando have noted, the SLFP needed the LSSP and Communist Party, rather than the other way around. In the face of mass protests and strikes in 1962, the SLFP had been on the verge of complete collapse. The anti-coalitionists in the LSSP, having established themselves as the LSSP-R, contended later on that the LSSP could have made use of this opportunity to topple the government.

Whether or not the LSSP could have done this, one can’t really tell. However, regardless of what the LSSP chose to do, it must be pointed out that these decades saw the formation of several regimes in the Third World which posed as alternatives to Stalinism and capitalism. Moreover, the LSSP’s decision enabled it to see through certain important reforms. These included Workers’ Councils. Critics of these measures can point out, as they have, that they could have been implemented by any other regime. But they weren’t. And therein lies the rub: for all its failings, and for a brief period at least, the LSSP-CP-SLFP coalition which won elections in 1970 saw through something of a revolution in the country.

The writer is an international relations analyst, researcher, and columnist based in Sri Lanka who can be reached at udakdev1@gmail.com

-

Features3 days ago

Features3 days agoWhy does the state threaten Its people with yet another anti-terror law?

-

Features3 days ago

Features3 days agoReconciliation, Mood of the Nation and the NPP Government

-

Features3 days ago

Features3 days agoVictor Melder turns 90: Railwayman and bibliophile extraordinary

-

Features2 days ago

Features2 days agoLOVEABLE BUT LETHAL: When four-legged stars remind us of a silent killer

-

Features3 days ago

Features3 days agoVictor, the Friend of the Foreign Press

-

Latest News5 days ago

Latest News5 days agoNew Zealand meet familiar opponents Pakistan at spin-friendly Premadasa

-

Latest News5 days ago

Latest News5 days agoTariffs ruling is major blow to Trump’s second-term agenda

-

Latest News5 days ago

Latest News5 days agoECB push back at Pakistan ‘shadow-ban’ reports ahead of Hundred auction