Foreign News

Asante Gold: UK to loan back Ghana’s looted ‘crown jewels’

The UK is sending some of Ghana’s “crown jewels” back home, 150 years after looting them from the court of the Asante king.

A gold peace pipe is among 32 items returning under long-term loan deals, the BBC can reveal.

The Victoria & Albert Museum (V&A) is lending 17 pieces and 15 are from the British Museum.

Ghana’s chief negotiator said he hoped for “a new sense of cultural co-operation” after generations of anger.

Some national museums in the UK – including the V&A and the British Museum – are banned by law from permanently giving back contested items in their collections, and loan deals such as this are seen as a way to allow objects to return to their countries of origin. But some countries laying claim to disputed artifacts fear that loans may be used to imply they accept the UK’s ownership.

Tristram Hunt, director of the V&A, told the BBC that the gold items of court regalia are the equivalent of “our Crown Jewels”.

The items to be loaned, most of which were taken during 19th-Century wars between the British and the Asante, include a sword of state and gold badges worn by officials charged with cleansing the soul of the king.

Mr Hunt said when museums hold “objects with origins in war and looting in military campaigns, we have a responsibility to the countries of origin to think about how we can share those more fairly today. “It doesn’t seem to me that all of our museums will fall down if we build up these kind of partnerships and exchanges.”

However, Mr Hunt insisted the new cultural partnership “is not restitution by the back door” – meaning it is not a way to return permanent ownership back to Ghana.

The three-year loan agreements, with an option to extend for a further three years, are not with the Ghanaian government but with Otumfo Osei Tutu II – the current Asante king known as the Asantehene – who attended the Coronation of King Charles last year. The Asantehene still holds an influential ceremonial role, although his kingdom is now part of Ghana’s modern democracy.

The items will go on display at the Manhyia Palace Museum in Kumasi, the capital of the Asante region, to celebrate the Asantehene’s silver jubilee.

The Asante gold artifacts are the ultimate symbol of the Asante royal government and are believed to be invested with the spirits of former Asante kings.

They have an importance to Ghana comparable to the Benin Bronzes – thousands of sculptures and plaques looted by Britain from the palace of the Kingdom of Benin, in modern-day southern Nigeria. Nigeria has been calling for their return for decades.

Nana Oforiatta Ayim, special adviser to Ghana’s culture minister, told the BBC: “They’re not just objects, they have spiritual importance as well. They are part of the soul of the nation. It’s pieces of ourselves returning.” She said the loan was “a good starting point” on the anniversary of the looting and “a sign of some kind of healing and commemoration for the violence that happened”.

UK museums hold many more items taken from Ghana, including a gold trophy head that is among the most famous pieces of Asante regalia.

The Asante built what was once one of the most powerful and formidable states in west Africa, trading in, among others, gold, textiles and enslaved people.

The kingdom was famed for its military might and wealth. Even now, when the Asantehene shakes hands on official occasions, he can be so weighed down with heavy gold bracelets that he sometimes has an aide whose job is to support his arm.

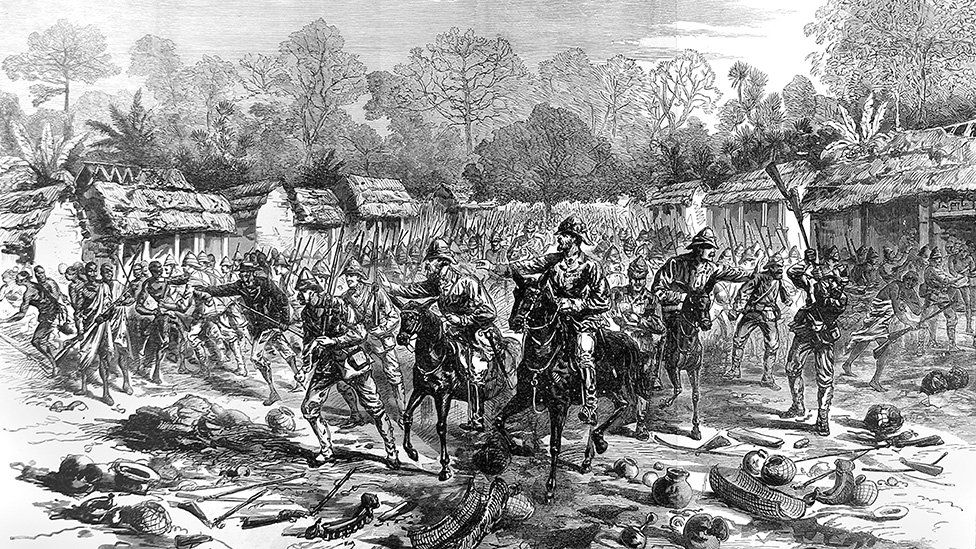

Europeans were attracted to what they later named the Gold Coast by the stories of African wealth and Britain fought repeated battles with the Asante in the 19th Century.

In 1874 after an Asante attack, British troops launched a “punitive expedition”, in the colonial language of the time, ransacking Kumasi and taking many of the palace treasures.

Most of the items the V&A is returning were bought at an auction on 18 April 1874 at Garrards, the London jewellers who maintain the UK’s Crown Jewels.

They include three heavy cast-gold items known as soul washers’ badges (Akrafokonmu), which were worn around the necks of high ranking officials at court who were responsible for cleansing the soul of the king.

Angus Patterson, a senior curator at the V&A, said taking these items in the 19th Century “was not simply about acquiring wealth, although that is a part of it. It’s also about removing the symbols of government or the symbols of authority. It’s a very political act”.

The British Museum is also returning on loan a total of 15 items, some of them looted during a later conflict in 1895-96, including a sword of state known as the Mpomponsuo.

There is also a ceremonial cap, known as a Denkyemke, richly decorated with gold ornaments. It was worn by senior courtiers at coronations and other major festivals.

The British Museum is also lending a cast-gold model lute-harp (Sankuo), which was not looted, to highlight its almost 200-year-old connection with the Asantehenes.

The sankuo was presented to the British writer and diplomat Thomas Bowdich in 1817, who said it was intended as a gift from the Asantehene to the museum to demonstrate the wealth and status of the Asante nation.

Can you loan objects back to a country that says you stole them?

It’s a solution to UK legal restrictions that may not be acceptable to countries which say they want to right a historic wrong.

The issue of the Parthenon Sculptures, or Elgin Marbles as they were named in the UK, is the best-known example.

Greece has long demanded the return of these classical sculptures that are displayed in the British Museum. Its chair of trustees, George Osborne, recently said that he was looking for a “practical, pragmatic and rational way forward” and was exploring a partnership that, in essence, puts the question of who actually owns the classical sculptures to one side.

This agreement with the Asantehene is another version of that; a compromise that works for the Asante king and is possible within the parameters of British law.

Just as Nigeria would be unlikely to accept a loan of the Benin Bronzes, it would have been difficult for Ghana’s government to accept this kind of agreement.

But Mr Hunt said the deals between the V&A, the British Museum and the Manhyia Palace Museum “cut through the politics. It doesn’t solve the problem, but it begins the conversation”.

Ms Oforiatta Ayim, the Ghana culture minister’s adviser, said “of course” people will be angry at the idea of a loan and they hoped to see items eventually returned permanently to Ghana. “We know the objects were stolen in violent circumstances, we know the items belong to the Asante people,” she said.

The British government has a “retain and explain” stance for state-owned institutions, which means contested objects are kept and their context is explained.

Neither the Conservative nor Labour parties have signalled any interest in changing current legislation. The British Museum Act of 1963 and the National Heritage Act of 1983 prevent museum trustees at some high-profile institutions from “deaccessioning” items in their collections.

Mr Hunt is advocating a change in the law. He would like to see “more freedom for museums, but then a kind of backstop, a committee where we would have to appeal if we wanted to restitute items”.

Some have raised concerns this would mean British museums losing some of their most prized items in future. Or as a previous culture secretary, Michelle Donelan, put it to me in relation to a return of the Parthenon Sculptures, that it would “open the gateway to the question of the entire contents of our museums”.

But Mr Hunt said the ownership of very few of the V&A’s collection of 2.8 million items has been disputed.

Another fear is that contested items that go on loan will never be returned.

Ghana’s chief negotiator Ivor Agyeman-Duah scotched that. “You stick to agreements that you have, you don’t go against them,” he said.

There are other beautiful Asante gold items in the UK. The Wallace Collection includes the trophy head which is among the most famous Asante treasures. It too was taken by British forces and bought at the 1874 auction.

The Royal Collection also holds objects including another gold trophy head in the form of a mask. This type of item represented defeated enemies; the trophies were attached by a hoop to ceremonial swords in the state regalia.

Will they ever be on show in Ghana in future? Mr Adyeman-Duah is taking it one step at a time.

But as Britain is increasingly confronting the cultural legacy of its colonial past, these types of agreements may be a diplomatic and practical way to address the past and create better relationships in the future – if both sides can accept the terms.

(BBC)

Foreign News

War photographer Paul Conroy dies as tributes paid

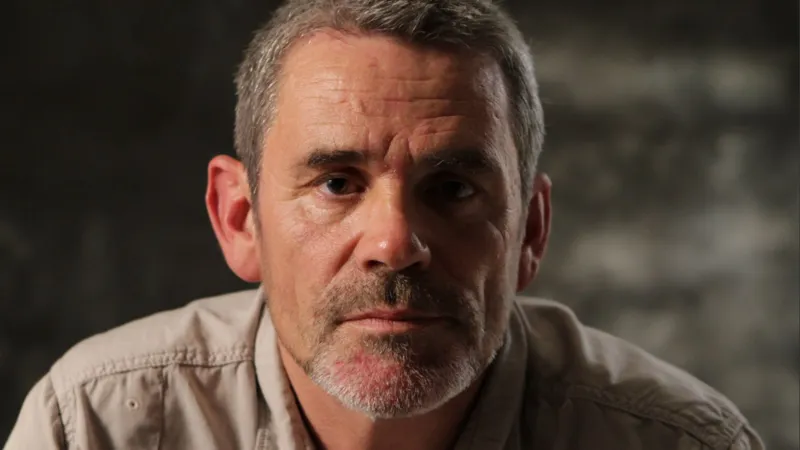

Tributes have been paid to the war photographer Paul Conroy who has died at the age of 61.

He covered conflicts around the world and was wounded in the Syrian army’s bombardment of Homs, which killed his Sunday Times colleague Marie Colvin in 2012.

Their fateful assignment was depicted in the 2018 movie A Private War, with the actor Jamie Dornan playing Conroy.

The Liverpool-born photographer died from a heart attack on Saturday in Devon, where he had lived, his brother Alan told the BBC.

“He did all his life what he wanted to do to make a difference – he found great pleasure in exposing wrongs,” Alan added.

BBC newsreader Clive Myrie posted that he was “utterly devastated” by the news, describing Conroy as “a wonderful photojournalist and a wonderful human being”.

“I counted him as a friend and a decent, principled and kind man. My brutha you will be sorely missed. RIP”

Lindsey Hilsum, international editor at Channel 4, added: “All of us who knew and loved him are devastated.”

Conroy also spent seven years with the Royal Artillery as a soldier before becoming a professional photographer and was a trustee of the Frontline Club for media professionals, diplomats and aid workers.

Its founder Vaughan Smith, who was also in the Army, said: “He was one of the characters – those people who stand out because everybody adores them and they make you feel better.”

The 2018 documentary Under the Wire was made about Conroy’s escape from the 2012 bombardment of a makeshift media centre in Homs, where his colleagues Marie Colvin and Remi Ochlik were killed.

Referring to the Syrians who were killed in the area, he said: “These beautiful people who were being slaughtered, I wanted to tell their story.”

He only realised how badly injured he was when he returned to the UK.

“Obviously I knew I had a huge hole in the back of my leg,” he said.

“But in London I found out I also had a great big piece of shrapnel wedged under my kidneys. I had 23 operations on my leg and others on my abdomen and back. I was in hospital for five months.”

Conroy worked in Libya and Ukraine and had recently returned from an assignment in Cuba.

He also took photos for the British singer Joss Stone and wrote music with her.

She said she was “so grateful to have known him and honoured to call him my friend”.

“I wouldn’t be the person I am today without Paul. Paul Conroy was a legend. A wonderful person through and through. Always standing up for what was right. Always there for those in need.”

He leaves behind a wife, three sons and grandchildren.

[BBC]

Foreign News

Iran begins 40-day mourning after Khamenei killed in US-Israeli attack

Iran has begun 40 days of mourning after Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei was killed in ongoing attacks by the United States and Israel, according to Iranian state media.

Top security officials were also killed in Saturday’s strikes, along with Khamenei’s daughter, son-in-law and grandson. The killings mark one of the most significant blows to Iran’s leadership since the 1979 Islamic revolution.

President Masoud Pezeshkian condemned the killing as “a great crime”, according to a statement from his office. He also declared seven days of public holidays in addition to the 40-day mourning period.

Reporting from Tehran, Al Jazeera’s Tohid Asadi said people were pouring into the streets of the capital following the news of Khamenei’s killing.

“There will be expected ceremonies,” he said, noting they would likely take place amid continuing bombardment across the country.

Protests denouncing Khamenei’s killing were also reported elsewhere, including Shiraz, Yasuj and Lorestan.

Footage aired by Iranian state media showed supporters mourning at the shrine of Imam Reza in Mashhad, with several people seen crying and collapsing in grief.

The killing also led to protests in neighbouring Iraq, which declared three days of public mourning. In Baghdad, protesters confronted security forces in the heavily fortified Green Zone, which houses Iraqi government buildings and foreign embassies.

Videos verified by Al Jazeera showed demonstrators waving flags and shouting slogans, with witnesses saying some were attempting to mobilise towards the US Embassy. Footage also showed protesters blocking vehicles at a roundabout near one of the entrances to the area.

There was also a protest in the Pakistani city of Karachi, where footage, verified by Al Jazeera, showed people setting fire to and smashing the windows of the US consulate.

However, there have also been reports of celebrations in Iran, with the Reuters news agency quoting witnesses as saying some people had taken to the streets in Tehran, the nearby city of Karaj and the central city of Isfahan.

Meanwhile, the official IRNA news agency reported that a three-person council, consisting of the country’s president, the chief of the judiciary, and one of the jurists of the Guardian Council, will temporarily assume all leadership duties in the country. The body will temporarily oversee the country until a new supreme leader is elected.

Khamenei assumed leadership of Iran in 1989 following the death of Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini, who had led the Islamic revolution a decade earlier.

While Khomeini was regarded as the ideological force behind the revolution that ended the Pahlavi monarchy, Khamenei went on to shape Iran’s military and paramilitary apparatus, strengthening both its domestic control and its regional influence.

Meanwhile, the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC) pledged revenge and said it had launched strikes on 27 bases hosting US troops in the region, as well as Israeli military facilities in Tel Aviv.

[Aljazeera]

Foreign News

Briton among 19 killed in Nepal bus crash

A 24-year-old British man is among 19 people who were killed in a bus crash in Nepal, police say.

The bus – which had been carrying tourists – had been travelling to the capital, Kathmandu, when it lost control and fell 200m on to the bank of the Trishuli river, in the country’s central Dhading district, in the early hours of Monday morning.

There were 44 people onboard including the driver, 25 of whom suffered injuries. The bus had been travelling from Pokhara, a popular tourist spot.

Nepal’s Home Ministry has created a five-member taskforce to investigate the cause of the incident. The UK Foreign Office said it was assisting the family of the Briton who was killed.

Nepalese authorities identified him as Stewart Dominic Ethan. His name has not been confirmed by the Foreign Office.

Nepalese police say they have identified all 19 bodies, including a 40-year-old Chinese woman and a 32-year-old man from India. Among the injured is a Chinese national and a New Zealander.

All the injured had been taken to hospitals in the capital, they added. Children were among those onboard.

Multiple teams were sent to the site, including police units, the army and a rescue team of divers, authorities said.

Police spokesman Abinarayan Kafle said 17 people died at the scene, with two more dying while receiving treatment, BBC Nepali reported.

Road accidents are relatively commonplace in Nepal, due to a range of factors including poor road maintenance and narrow paths in mountainous areas.

In 2024, at least 14 people died after a bus travelling from Pokhara to Kathmandu fell into the Marsyangdi river in the Tanahun district.

“We are supporting the family of a British man who has died in Nepal and are in contact with the local authorities,” a Foreign Office spokesman told the BBC.

Nepal is a popular destination for many international visitors, especially climbers, who travel there to access a key section of the Himalaya mountain range that includes Mount Everest.

Home to eight of the world’s tallest peaks, mountaineering is a significant source of revenue for the country – in 2024 climbing fees brought in $5.9m.

[BBC]

-

Opinion4 days ago

Opinion4 days agoJamming and re-setting the world: What is the role of Donald Trump?

-

Features4 days ago

Features4 days agoAn innocent bystander or a passive onlooker?

-

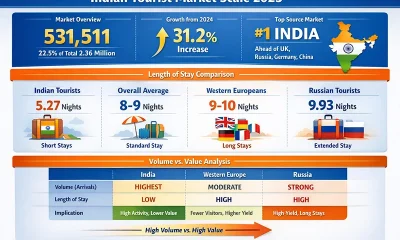

Features6 days ago

Features6 days agoBuilding on Sand: The Indian market trap

-

Opinion6 days ago

Opinion6 days agoFuture must be won

-

Features5 days ago

Features5 days agoRatmalana Airport: The Truth, The Whole Truth, And Nothing But The Truth

-

Business6 days ago

Business6 days agoDialog partners with Xiaomi to introduce Redmi Note 15 5G Series in Sri Lanka

-

Business5 days ago

Business5 days agoIRCSL transforms Sri Lanka’s insurance industry with first-ever Centralized Insurance Data Repository

-

Sports7 days ago

Sports7 days agoCEA halts development at Mandativu grounds until EIA completion