Features

Anuradhapura Teaching Hospital – an encomium

To understand the strength of a fellow human being, you don’t have to enter a wrestling match; you only have to observe how the men and women in a hospital heal patients.

The following is the magnanimity of human nature explained in a nutshell. This story is not fiction or hearsay. These are compelling comments on humanity, bravery, strength, life, and sadly, death, I witnessed firsthand recently during my three-day stay in Ward 61 at the Anuradhapura Teaching Hospital for fever, chest pain, buildup of fluid in the space around my heart, and a few other problems. This hospital has been a medical outpost since its inception in the 1950s. However, after it became a teaching hospital, the whole institution gained wide recognition and gave new meaning to all things health in the region. It is the third largest hospital in Sri Lanka.

Now, its Wards are not just numbers; they distribute the highest brands of medical expertise. They are not your run-of-the-mill half-walled hospital Wards, but bursting with knowledge Hippocrates worked all his life to master.

Wards 61 and 62 are Professorial Wards served by devoted, brilliant men and women of the highest medical learning and authority. They make these places sacred by healing. Descendants of Dhanvantari (doctor to Devas) and Saint Sebastian (Saint of Medicine) take turns to walk the hallways here with stethoscopes dangling in their hands. White-crowned nurses attend and show kindness to patients as if they were their children.

I was in the High Dependency Unit (HDU) of Ward 61 with three other patients who were attached to electronic monitors, which provided nonstop beeping symphonies to my tired ears. Before long, I thought I was sitting in the orchestra pit of an opera house, where musicians were tuning their instruments before the start of the show. This whole time, my wife, Niranjala, the angel of angels, held my hand, helping me with soothing words to ease my pain and worries.

We watched nurses light up the Ward, walking among beds with purposeful and determined faces, talking and listening, offering soothing words to patients in various states of pain and suffering.

Meanwhile, inside the HDU, two young men wearing short-sleeved shirts and sarongs were standing by the beds of the two elderly patients, their fathers, who were in a sedated state. One father had ingested poison, and the other had advanced liver failure, a common health issue in the North Central province.

When I dozed off and woke up later in the middle of the night, a team of nurses gathered around one of these patients, holding various medical items in their raised hands. One was pushing an Artificial Manual Breathing Unit (AMBU) like the bellows at a smithy. Every so often, she wiped the sweat off her forehead. The patient’s son stood at a far corner, watching this determined group of strangers trying to save his father’s life. As this life’s drama unfolded, the other man held his father’s hand and watched in stunned and palsied silence.

We would never know the unfathomable weight of the hearts of the two men watching their fathers fight for their lives. That night, these young men were the two loneliest people on the planet.

At dawn, I saw the father they were trying to save lying alone on his bed, wrapped in blankets from head to toe. His overhead electronic screen had gone dark, and the tubing hanging lifeless above the headstand. Life had the rendezvous with its nemesis, and death won.

A few hours later, the son came to pick up his father’s items from the nurse. As we made eye contact, I nodded my heartfelt thoughts to him.

Doctor-fledglings ready to fly out

Next, as the Ward woke up, my eyes caught a heartening moment you would not see in any other work environment. A tall pedagogue, probably in his late 50s and athletic-looking, led a group of young men and women clad in deep, turquoise-shaded trousers and short-sleeved shirts. They earnestly listened to him while holding notebooks and stethoscopes on their bosoms.

With each step he takes, these young men and women, medical students at the Rajarata University Medical School, follow suit in unison. The tall figure with crew-cut hair is Professor of Medicine, Sisira Siribaddana, a giant of a man of academic standing. He has crossed oceans of medical expertise. Teaching students and treating patients are two inevitably tough propositions. He is one of the busiest doctors/teachers around here. But his articulation was appealing and mesmerized the students, who watched as if they were listening to a Himalayan Irshi.

The students followed the professor through the Ward like a flock of goslings following the mother goose who led them to shore.

Little did they know, soon they would be on their own. They will not have the pleasure of flying in formation like a skein on holidays and on outings on weekends you and I take for granted. They will become fully-fledged lifesavers, often sleeping in converted staff rooms in the hospital while on call or floating alone in turbulent spells of medical winter blizzards.

Amid their study sessions, these fledgling doctors also return to continue looking after the patients late into the night. Time of day is not an issue for them. They are cued by impeccable dedication to patients and show superlative energy for observing and learning, embodying the demands and responsibilities of the job they will soon be charged with outside the comfort under the eyes of the professors.

Even after going home this time around, the patients know that whatever future ailments they will get, they are in good hands. What these medical students try to learn is all under our skin – unseen, entwined with hundreds of potential disorders in the limitless and complex miracle we call our all-scented and well-groomed bodies. Unlike engineers who rarely touch water for fear of electrocution, these students read and interpret blood and other body fluids. They study what boils under our skin. They count the pulse because it matters to them as much as to their patients. These future doctors become so good at what they do that by the time we, the patients, are ready to go home, they have seen through us enough to write our biographies by heart.

Tutored by a cognoscente of Jeewaka pedigree, they will do just fine because they are also the cream of the cream and earned the right and honour to follow the footsteps of Siribaddana-class of great teachers. With the earnest look on their faces, we have nothing to fear. Professor Siribaddana and his academic colleagues will prepare them to hit the road to medical miracles like flashes of a just-offloaded fleet of Lexuses.

I am helpless searching for words to express my appreciation to Professor Sisira Siribaddana, Senior Professor and Chair of Medicine, Drs. Isuru Ahesh, Priyadharshan, Sampavi Ramanan in Ward 61, and Dr. Arulkumar Jegavanthan, one of the cardiologists in the hospital, for the excellent medical care they rendered to me.

Nurses and Other Staff

The nursing staff’s immaculate service furthers the doctors’ mission. Nurses and the minor staff are the other pieces of the backbone of this Ward. They hold this place together, preventing it from drifting into chaos. They encourage and offer kind words to dejected patients.

These nurses are in a marathon to win together. They are regular folks like you and me. They are fathers and mothers, often with two or three kids, constantly worrying about whether the kids came home from school or tuition classes and had dinner. I know it. My niece, Uditha, a nurse in this hospital, has two kids. While at work, I know how much she worries about her preschooler daughter and the 9-month-old son at home. Then there are young nurses just out of nursing school yearning for the time to be out with a cupid.

Patience in nurses is a remarkable science that somebody must teach in schools and public counters in government offices. Nursing vocabulary does not have the word “tiredness.” Never angry, never in haste, they exude unmatched professionalism and kindness. Those in other government offices must emulate the work ethic of these men and women. They are our Florence Nightingales. They are healers in our midst. Next time you see someone you know as a nurse standing on the bus or in a queue at the bank, get up and give her the seat or step aside and offer her the place in the line. She has earned every inch of that space much more than anyone in that place. If you fail to do it, I think you must seek counseling help.

Hospital Needs Immediate Attention.

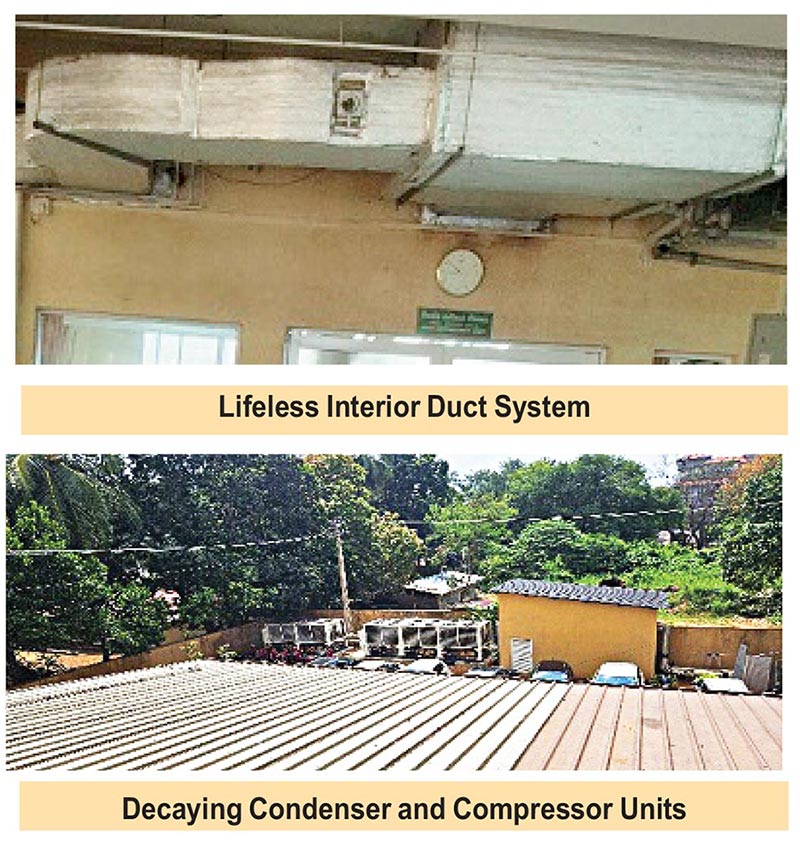

Yet, some things here need immediate attention. The central air conditioning system of this multi-story building is out of commission for some time, and its lorry-sized condenser and compressor unit sit in the open garden, uncovered, lifeless, and decaying. Its inert ducts hang on the ceiling like fossilised long-necked dinosaurs. Some suspect that rat infestation has infiltrated the duct system. During this time of the year, the dry zone sun is on the job full force, and without working air conditioners, rooms are hot like incubators. Patients take the brunt of the heat punishment.

In contrast, what I found elsewhere a few weeks later completely flabbergasted me. I was in a 17-storey government building (not a hospital) in Battaramulla, near Colombo. In this building, the central air conditioning system worked flawlessly, so it felt like its ducts system drew air directly from the Arctic Circle.

Decaying Condenser and Compressor Units

Immediately after my discharge from the hospital, Niranjala and I asked Professor Siribaddana if there was anything we could donate to the Ward. Having experienced the intolerable heat firsthand, we discussed the inconvenience that patients go through due to a lack of air conditioning in the HDU. We got his consent to donate two air conditioning units for the HDU in Ward 61 and later to donate two more units to the HDU in its sister Ward 62, which hosts female patients. We are happy that the four LG 18000BTU air conditioning units we donated are now working, providing much-needed relief to critical patients housed in the HDUs. Sadly, this building has more Wards and units without air conditioning. I hope that by bringing this issue to light, relevant authorities will take immediate steps, or any benefactors out there will think of providing some relief.

Furthermore, hospital staff are taking proactive steps to improve the hospital’s working environment. For example, recently, after considering the safety and convenience of the doctors on call in the Wards, Professor Siribaddana and his colleagues in the two Wards purchased air conditioners with their own money and installed them in two rooms previously used for storage. They converted it into rooms for on-call doctors to stay overnight. Now, after work, the on-call doctors do not have to step outside into the dark, deserted streets tethered to predatory elements. The consultants in the Department coming out with a creative and indispensable gesture to resolve this dire situation is a noble act.

When Niranjala and I visited the library upstairs with Dr. Hemal Senanayake, the Head of the Department of Medicine, we walked past the 250-seat auditorium. There, we saw the seat covers of nearly all chairs torn away and the exposed cushion foam falling apart and dissolving into pieces. We hope the authorities fix this problem soon. Meanwhile, we heard a generous group recently equipped the auditorium with air conditioning facilities.

After I left the Ward, I returned to Ward 61 twice daily, a few times, to get my antibiotic through IV. By now, I have begun to miss the staff here. This is a government hospital. Its hallway walls may not have mounted George Keyts reproductions or framed pictures of cherubic babies with adoring smiles. But the weight and pains of ordinary people from all walks of life beautify its floors and corridors.

Actor Robin Williams, playing British/American neurologist Oliver Sacks in the 1990 movie Awakenings, declared, “The human spirit is more powerful than any other drug.” I found the doctors, nurses, and other minor staff in Wards 61 and 62 surely fostering this attribute, the cornerstone of any healing facility. Thus, I would not hesitate to return to Ward 61 for a second tour, because I trust these people with my life.

by Lokubanda Tillakaratne

Features

The Paradox of Trump Power: Contested Authoritarian at Home, Uncontested Bully Abroad

The Trump paradox is easily explained at one level. The US President unleashes American superpower and tariff power abroad with impunity and without contestation. But he cannot exercise unconstitutional executive power including tariff power without checks and challenges within America. No American President after World War II has exercised his authority overseas so brazenly and without any congressional referral as Donald Trump is getting accustomed to doing now. And no American President in history has benefited from a pliant Congress and an equally pliant Supreme Court as has Donald Trump in his second term as president.

Yet he is not having his way in his own country the way he is bullying around the world. People are out on the streets protesting against the wannabe king. This week’s killing of 37 year old Renee Good by immigration agents in Minneapolis has brought the City to its edge five years after the police killing of George Floyd. The lower courts are checking the president relentlessly in spite of the Supreme Court, if not in defiance of it. There are cracks in the Trump’s MAGA world, disillusioned by his neglect of the economy and his costly distractions overseas. His ratings are slowly but surely falling. And in an electoral harbinger, New York has elected as its new mayor, Zoran Mamdani – a wholesale antithesis of Donald Trump you can ever find.

Outside America it is a different picture. The world is too divided and too cautious to stand up to Trump as he recklessly dismantles the very world order that his predecessors have been assiduously imposing on the world for nearly a hundred years. A few recent events dramatically illustrate the Trump paradox – his constraints at home and his freewheeling abroad.

Restive America

Two days before Christmas, the US Supreme Court delivered a rare rebuke to the Trump Administration. After a host of rulings that favoured Trump by putting on hold, without full hearing, lower court strictures against the Administration, the Supreme Court by a 6-3 majority decided to leave in place a Federal Court ruling that barred Trump from deploying National Guard troops in Chicago. Trump quietly raised the white flag and before Christmas withdrew the federal troops he had controversially deployed in Chicago, Portland and Los Angeles – all large cities run by Democrats.

But three days after the New Year, Trump airlifted the might of the US Army to encircle Venezuela’s capital Caracas and spirit away the country’s President Nicolás Maduro, and his wife Celia Flores, all the way to New York to stand trial in an American Court. What is not permissible in any American City was carried out with absolute impunity in a foreign capital. It turns out the Administration has no plan for Venezuela after taking out Maduro, other than Trump’s cavalier assertion, “We’re going to run it, essentially.” Essentially, the Trump Administration has let Maduro’s regime without Maduro to run the country but with the US in total control of Venezuela’s oil.

Next on the brazen list is Greenland, and Secretary of State Marco Rubio who manipulated Maduro’s ouster is off to Copenhagen for discussions with the Danish government over the future of Greenland, a semi-autonomous part of Denmark. Military option is not off the table if a simple real estate purchase or a treaty arrangement were to prove infeasible or too complicated. That is the American position as it is now customarily announced from the White House podium by the Administration’s Press Secretary Karolyn Leavitt, a 28 year old Catholic woman from New Hampshire, who reportedly conducts a team prayer for divine help before appearing at the lectern to lecture.

After the Supreme Court ruling and the Venezuela adventure, the third US development relevant to my argument is the shooting and killing of a 37 year old white American woman by a US Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) officer in Minneapolis, at 9:30 in the morning, Wednesday, January 7th. Immediately, the Administration went into pre-emptive attack mode calling the victim a “deranged leftist” and a “domestic terrorist,” and asserting that the ICE officer was acting in self-defense. That line and the description are contrary to what many people know of the victim, as well as what people saw and captured on their phones and cameras.

The victim, Renee Nicole Good, was a mother of three and a prize-winning poet who self-described herself a “poet, writer, wife and mom.” A newcomer to Minneapolis from Colorado, she was active in the community and was a designated “legal observer of Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) activities,” to monitor interactions between ICE agents and civilian protesters that have become the norm in large immigrant cities in America. Renee Good was at the scene in her vehicle to observe ICE operations and community protesters.

In video postings that last a matter of nine seconds, two ICE officers are seen approaching Good’s vehicle and one of them trying to open her door; a bystander is heard screaming “No” as Good is seen trying to drive away; and a third ICE officer is seen standing in front of her moving vehicle, firing twice in the direction of the driver, moving to a side and firing a third time from the side. Good’s car is seen going out of control, careening and coming to a stop on a snowbank. Yet America is being bombarded with two irreconcilable narratives – one manufactured by Trump’s Administration and the other by those at the scene and everyone opposed to the regime.

It adds to the explosiveness of the situation that Good was shot and killed not far from where George Folyd was killed, also in Minneapolis, on 25th May, 2020, choked under the knee of a heartless policeman. And within 48 hours of Good’s killing, two Americans were shot and injured by two federal immigration agents, in Portland, Oregon, on the Westcoast. Trump’s attack on immigrants and the highhanded methods used by ICE agents have become the biggest flashpoint in the political opposition to the Trump presidency. People are organizing protests in places where ICE agents are apprehending immigrants because those who are being aggressively and violently apprehended have long been neighbours, colleagues, small business owners and students in their communities.

Deportation of illegal immigrants is not something that began under Trump. It has been going on in large numbers under all recent presidents including Obama and Biden. But it has never been so cruel and vicious as it is now under Trump. He has turned it into a television spectacle and hired large number of new ICE agents who are politically prejudiced and deployed them without proper training. They raid private homes and public buildings, including schools, looking for immigrants. When faced with protesters they get into clashes rather than deescalating the situation as professional police are trained to do. There is also the fear that the Administration may want to escalate confrontations with protesters to create a pretext for declaring martial law and disrupt the midterm congressional elections in November this year.

But the momentum that Trump was enjoying when he began his second term and started imposing his executive authority, has all but vanished and all within just one year in office. By the time this piece appears in print, the Supreme Court ruling on Trump’s tariffs (expected on Friday) may be out, and if as expected the ruling goes against Trump that will be a massive body blow to the Administration. Trump will of course use a negative court ruling as the reason for all the economic woes under his presidency, but by then even more Americans would have become tired of his perpetually recycled lies and boasts.

An Obliging World

To get back to my starting argument, it is in this increasingly hostile domestic backdrop that Trump has started looking abroad to assert his power without facing any resistance. And the world is obliging. The western leaders in Europe, Canada and Australia are like the three wise monkeys who will see no evil, hear no evil and speak no evil – of anything that Trump does or fails to do. Their biggest fear is about the Trump tariffs – that if they say anything critical of Trump he will magnify the tariffs against their exports to the US. That is an understandable concern and it would be interesting to see if anything will change if the US Supreme Court were to rule against Trump and reject his tariff powers.

Outside the West, and with the exception of China, there is no other country that can stand up to Trump’s bullying and erratic wielding of power. They are also not in a position to oppose Trump and face increased tariffs on their exports to the US. Putin is in his own space and appears to be assured that Trump will not hurt him for whatever reason – and there are many of them, real and speculative. The case of the Latin American countries is different as they are part of the Western Hemisphere, where Trump believes he is monarch of all he surveys.

After more than a hundred years of despising America, many communities, not just regimes, in the region seem to be warming up to Trump. The timing of Trump’s sequestering of Venezuela is coinciding with a rising right wing wave and regime change in the region. An October opinion poll showed 53% of Latin American respondents reacting positively to a then potential US intervention in Venezuela while only 18% of US respondents were in favour of intervention. While there were condemnations by Latin American left leaders, seven Latin American countries with right wing governments gave full throated support to Trump’s ouster of Maduro.

The reasons are not difficult to see. The spread of crime induced by the commerce of cocaine has become the number one concern for most Latin Americans. The socio-religious backdrop to this is the evangelisation of Christianity at the expense of the traditional Catholic Church throughout Latin America. And taking a leaf from Trump, Latin Americans have also embraced the bogey of immigration, mainly influenced by the influx of Venezuelans fleeing in large numbers to escape the horrors of the Maduro regime.

But the current changes in Latin America are not necessarily indicative of a durable ideological shift. The traditional left’s base in the subcontinent is still robust and the recent regime changes are perhaps more due to incumbency fatigue than shifts in political orientations. The left has been in power for the greater part of this century and has not been able to provide answers to the real questions that preoccupied the people – economic affordability, crime and cocaine. It has not been electorally smart for the left to ignore the basic questions of the people and focus on grand projects for the intelligentsia. Exhibit #1 is the grand constitutional project in Chile under outgoing President Gabriel Borich, but it is not the only one. More romantic than realistic, Boric’s project titillated liberal constitutionalists the world over, but was roundly rejected by Chileans.

More importantly, and sooner than later, Trump’s intervention in Venezuela and his intended takeover of the country’s oil business will produce lasting backlashes, once the initial right wing euphoria starts subsiding. Apart from the bully force of Trump’s personality, the mastermind behind the intervention in Venezuela and policy approach towards Latin America in general, is Secretary of State Marco Rubio, the former Cuban American Senator from Florida and the principal leader of the group of Cuban neocons in the US. His ultimate objective is said to be achieving regime change in Cuba – apparently a psychological settling of scores on behalf Cuban Americans who have been dead set against Castro’s Cuba after the overthrow of their beloved Batista.

Mr. Rubio is American born and his parents had left Cuba years before Fidel Castro displaced Fulgencio Batista, but the family stories he apparently grew up hearing in Florida have been a large part of his self-acknowledged political makeup. Even so, Secretary Rubio could never have foreseen a situation such as an externally uncontested Trump presidency in which he would be able to play an exceptionally influential role in shaping American policy for Latin America. But as the old Burns’ poem rhymes, “The best-laid plans of men and mice often go awry.”

by Rajan Philips ✍️

Features

Unsuccessful attempt on President Chandrika’s life

The Presidential election campaign was drawing to a close. We had campaigned hard but everyone knew that it would be a keenly contested election. A final meeting was scheduled for Saturday December 18, 1999. It was to be held near the Town Hall in Colombo and CBK was to be the chief speaker. I was accommodated in the front row of the stage together with other party leaders.

Ratnasiri Wickremanayake, the Prime Minister, had invited me to be a speaker at his final meeting in Horana. I waited till CBK arrived, spoke briefly to her and left for Horana. I had barely reached Havelock Town when I heard the sound of a blast from near the Town Hall. It was a well planned attempt on the life of CBK by the LTTE. Suicide bombers had come into the well packed grounds with a group of supporters of a Colombo district SLFP MP. Fortunately they had been prevented from coming close to the stage by the barriers set up by the Police.

CBK had finished her speech to a packed audience and was going down the gangway from the stage to her car when the bomber had detonated his bomb killing himself, several policemen, CBKs driver and many onlookers. But for the fact that her driver had driven up to the steps, thereby interposing the steel reinforced Mercedes Benz car between the bomb and CBK she would have been torn to shreds.

When we inspected the Benz it was a mass of twisted metal like a futuristic sculpture. I forgot about Horana and immediately rushed to the general hospital where to my relief I was told that the President was alive and out of danger. Since I had experience of the bombing of the UNP group meeting in Parliament during JRJs time, I rushed to Temple Trees to find that Sunethra Bandaranaike had fortunately promptly come there and was with the children upstairs.

The Temple Trees staff congregating downstairs were wandering about in shock till the arrival of President’s Secretary Balapatabendi. I urged that we should immediately get down Anuruddha Ratwatte -the Deputy Defence Minister, who at that time was in Kandy. A problem arose because helicopters could not fly at night. He was asked to come immediately by road and he did arrive in the shortest time.

In the meanwhile I suggested that Balapatabendi should broadcast the news that CBK was alive and out of danger as we had done with JRJ after the Parliament bombing. Already news about the attack was swirling because international media was using it as “Breaking News”. Bala and I went to the TV station and as he was getting into the studio I noticed that he was dressed in a black shirt which could have given a bad message to the country. I quickly took off my shirt and exchanged it for Balas black shirt. He then spoke on camera trying to calm the country wide audience dressed in an over-sized shirt.

We went back to Temple Trees and found that the PM and other Cabinet Ministers and relatives had arrived there and were taking charge of the situation. I then went to the General Hospital to see GL Peiris and Alavi Moulana who were in a state of shock and awaiting medical attention. Alavi’s shirt was blood stained and his sons were helplessly moving around asking for immediate medical attention.

After that both sides did not campaign in the remaining few days. The whole country was in a state of shock and disbelief. To the credit of Ranil Wickremesinghe he immediately visited CBK to wish her a speedy recovery and virtually called off his campaign. The shock of the Town Hall blast was compounded when almost at the same time a bomb was set off by the LTTE in Wattala where the UNP was holding a propaganda meeting. Major General Lucky Algama who was in charge of security was killed in this blast together with several UNP supporters.

Presidential Election December 2019

The presidential election was held as scheduled. We witnessed a clear shift of the sentiments of voters towards CBK after the bombing. I went to Kandy to cast my vote early as usual at the Nugawela voting centre. Immediately after that I left for Colombo. All along the road women of all ages were gathering in great numbers to cast their votes. It became clear that a sympathy vote was in the offing, especially among women. They could empathize with CBK who had lost a father and husband and now nearly lost her own life in the cause of public service.

The election results when announced proved that our hunch was correct. The declared results were as follows;

CBK

4,312,157 Votes [51.1 Percent]

Ranil

3,602,748 Votes [42.71 Percent]

Nandana Gunatillake

[JVP] 344,173 [4.08 Percent]

CBK then took a courageous decision which unfortunately backfired on her many years on as I will describe in a succeeding chapter. In the light of possible confusion following the bombing she decided to take her oath of office as the new President immediately though she had several months more to serve in terms of her earlier mandate. Though she had a team of brilliant lawyers including H L de Silva and R K W Goonesekere to advice on constitutional matters such details were not analyzed by her political staff. She took oaths before Chief Justice Sarath Nanda Silva and on the following day left for UK for medical treatment.

(Excepted from Vol. 3 of the Sarath Amunugma autobiography) ✍️

Features

My experience in turning around the Merchant Bank of Sri Lanka (MBSL)

LESSONS FROM MY CAREER: SYNTHESISING MANAGEMENT THEORY WITH PRACTICE – PART 29

The last episode covered the final stages of my work as Advisor to the National Productivity Drive at the Ministry of Industrial Development. Soon after, in September 1998, I accepted the position of Managing Director of the Merchant Bank of Sri Lanka (MBSL). This chapter shares key events and lessons from my time there.

First few weeks at MBSL

The Board agreed that, for the first month, I would work only half-days, as I still had obligations I could not abandon. I was organising the International Convention on Quality Circles 1998, which attracted many foreign participants, and although we had appointed an event organiser, numerous arrangements still required my involvement. I will write more about that Convention later in these memoirs.

Those half-days turned out to be useful. They allowed me to quietly observe and understand the situation. MBSL was in worse shape than I had expected. The financial problems were visible to anyone who read the statements. The bigger crisis, however, was the staff’s morale and the rapid loss of staff members.

During the interim management period, many staff benefits had been cut, and several senior executives had already left. In the first few months, farewell gatherings became routine. It felt like rats leaving a sinking ship. And indeed, the organisation was sinking. Yet I had accepted the challenge — largely because I sensed that the Chairperson could secure government support, which she had already begun to do.

The broader environment added to the tension. The LTTE conflict was still active. Our office building, a very tall building located near the Colpetty junction, was a prime target. It had an Air Force unit with anti-aircraft guns on the rooftop one floor above he boardroom.. No one was allowed there without special permission, even though the area had originally been designed as a rooftop function space.

The first board meeting was quite hilarious because, while we were discussing important strategic issues, the upper floor was reverberating with a baila session, with boots tapping the floor keeping time. Apparently, the unit had an assurance that there would be no air strikes, and they could take a break.

My own office was spacious, but the windows were blocked because Temple Trees — the official residence of the Prime Minister — was clearly visible if not. At first, working without any outside view felt quite oppressive. Eventually, I grew accustomed to it.

Once I began full-time work in October, I carefully examined the situation with the help of my capable team. Several senior employees were not leaving for higher-paying opportunities or foreign jobs — they were committed, though uncertain about the future.

Then came investigations by the Central Bank and the Securities and Exchange Commission. Much of my time was spent responding to information requests and ensuring that all releases of information were approved. Many years previously, MBSL had unintentionally become a subsidiary of the Bank of Ceylon (BOC) when BOC’s investment arm purchased shares that pushed ownership above 50 per cent.

Hence although we were not a deposit taking institution and therefore not under the regulatory oversight of the Central Bank, we were under the Central Bank scrutiny because we were a subsidiary of the BOC. Although we were independent in operations, the customary practice was that the BOC Chairman would also chair MBSL, together with other BOC directors serving on our board. Our Chairperson, Mrs Dayani de Silva, was determined to turn MBSL around.

At that time, we operated two main divisions:

· Corporate finance, including advisory and investment banking; and

· Leasing, including trade finance.

In addition, there were the service divisions such as Human Resources, Secretarial and Finance and Accounting

Staff matters and the trade union

Morale was low. staff resisted the benefit cuts and the shift toward rules that resembled those of government departments. Signing an attendance register was particularly disliked.

I reviewed the situation carefully. Some of the removed benefits saved only trivial amounts. I reinstated those. I also installed an electronic time-card system for everyone — including myself. I announced clearly that I would clock in every day, just as they did. Naturally, the first few months were not easy.

I began holding monthly staff meetings to explain what we were doing, why we were doing it, and where we stood financially. Communication had clearly been lacking earlier, and these meetings helped rebuild trust. I also operated an “open door” policy, welcoming any employee who wished to meet me. The performance appraisal system was another issue. Instead of motivating staff, it had become a source of resentment. I suspended it for two years and asked everyone to work together as one team.

Most employees up to the Deputy Manager level were unionised, affiliated with the Ceylon Bank Employees Union (CBEU), headed by Mr M. R. Shah. The collective agreement was due, and the union presented a long list of demands — many of them impossible, given our financial state. Normally, negotiations take place between the Employers’ Federation of Ceylon (EFC) and the CBEU. The Director General of the EFC, Mr Gotabhaya Dassanayake, advised me first to build mutual confidence, especially as I had never met Mr Shah before.

I invited Mr Shah to my office. Over tea, I openly explained the crisis we were facing, our restructuring plan, and the management approach we intended to adopt. He listened carefully and asked sensible questions. We parted on friendly terms, and more importantly, with a shared understanding.

A month later, negotiations began at the EFC. To my surprise, Mr Shah began by saying that, after speaking with the new Managing Director, he understood our difficulties and accepted the direction we were taking. He then withdrew several demands on the spot. I was relieved, not because demands were dropped, but because he had recognised our sincerity and our plan. Later, Mr Dassanayake telephoned to say he had rarely seen such cooperation. In time, as restructuring succeeded, we gradually restored many benefits. That entire episode reinforced a powerful lesson: honest communication and genuine leadership build trust far faster than confrontation.

Expanding leasing

The board was deeply concerned about the leasing division. Non-performing loans were very high, and they urged me to restrict new business and focus solely on recoveries. I informed the board that management was partly to blame because the staff was pressured to meet stretch targets, and all we got were substandard leasing facilities. Targets without safeguards are never beneficial.

My thinking differed. Aggressive recovery efforts often demoralise good customers and overburden staff. In addition, the customers were already in great difficulty because they had no financial means to meet their leasing obligations. Instead, I believed we needed to build a new, healthier portfolio, while also expanding fee-based advisory work with lower risk. I had also abandoned my consultancy business when I joined MBSL, and proposed creating a new subsidiary to bring that kind of business into the bank. The board rejected it – understandably, given past failures with subsidiaries, including one in Nepal.

We decided that if our leasing operations were to grow, they needed to feel more connected to ordinary Sri Lankans. Research revealed that many people viewed us as an “English-speaking bank.” That perception alone discouraged potential customers.

So, we refreshed our leasing brand. The new logo carried the Sinhala word for “leasing,” applications were printed in Sinhala, and signboards carried both languages. Even the telephone operator’s greeting changed. Instead of the polished “Good morning, MBSL,” which sometimes intimidated Sinhala-speaking callers, we switched to “Ayubowan, MBSL.” It was friendly, respectful, and immediately accepted across all segments.

When an SME business owner comes for a lease, they have already selected the vehicle, and the decision is more based on ego than on a business requirement. We would discourage them and enlighten them that the vehicle does not match their requirements, and advise them to select a smaller one. They look unhappy, but they finally agree when presented with the maths of repayment.

We also organised short educational sessions for our customers on how to maintain vehicles, extend tyre life, the importance of the correct lubricants, and improve customer service. These simple initiatives created goodwill, strengthened customer relationships, and soon, the leasing business began to grow. At the same time, we were tough on recoveries, and some unpleasant moments included we seized a vehicle when a couple was on their honeymoon. The board, while pressuring me to recover, also constantly reminded me that no strong-arm tactics should ever be used.

Improving cash availability

Before I joined, two government institutions had agreed to provide debentures, with Treasury comfort letters. However, a condition required us to build a monthly sinking fund for repayment. To me, this made little sense. We were already short of operating cash. Locking more away would only weaken us further.

The head of finance had faithfully followed the rule. I instructed him to stop doing so and to use the funds for business expansion. When the board asked how we planned to repay the debentures, my answer was simple: growing organisations borrow when repayment comes due — that is how business operates.

We also began selling off our minority shareholdings from our share portfolio wherever possible even at a loss. The market was depressed, and those investments in shares contributed nothing to our survival. We retained only the Merchant Credit of Sri Lanka and divested the others. Gradually, liquidity improved, and operations stabilised.

The thorny bonus issue

Before my arrival, the board had approved bonuses despite the 1997 crisis. I was surprised how it happened soon after chalking up a billion rupee loss. However, just three months into my tenure, the board refused the December 1998 bonus. I found myself in a painful position. The EFC warned that withholding payment was risky because bonuses were written into appointment letters. Yet, reality was clear — we simply could not afford it.

I addressed the staff personally, explained the situation frankly, and announced the decision. The disappointment was visible everywhere. But given the circumstances, they accepted it.

There were more challenges and many more lessons still to come. In the next article, I will continue the story of how, step by step, we navigated those difficulties and rebuilt the organisation.

(The writer is a Consultant on Productivity and Japanese Management Techniques

Retired Chairman/Director of several listed and unlisted companies

Recipient of the APO Regional Award for Promoting Productivity in the Asia-Pacific Region

Recipient of the Order of the Rising Sun, Gold and Silver Rays from the Government of Japan

Email: bizex.seminarsandconsulting@gmail.com)

By Sunil G. Wijesinha ✍️

-

News5 days ago

News5 days agoInterception of SL fishing craft by Seychelles: Trawler owners demand international investigation

-

News5 days ago

News5 days agoBroad support emerges for Faiszer’s sweeping proposals on long- delayed divorce and personal law reforms

-

Opinion2 days ago

Opinion2 days agoThe minstrel monk and Rafiki, the old mandrill in The Lion King – II

-

Features2 days ago

Features2 days agoThe Venezuela Model:The new ugly and dangerous world order

-

Latest News1 day ago

Latest News1 day agoRain washes out 2nd T20I in Dambulla

-

Business1 day ago

Business1 day agoSevalanka Foundation and The Coca-Cola Foundation support flood-affected communities in Biyagama, Sri Lanka

-

News4 days ago

News4 days agoPrez seeks Harsha’s help to address CC’s concerns over appointment of AG

-

News6 days ago

News6 days agoPrivate airline crew member nabbed with contraband gold