Features

Anti-corruption poster boy throws down gauntlet

Interview with Roshan Ranasinghe:

… vows to mobilise masses to oust corrupt govt. leaders

by Saman Indrajith

Roshan Ranasinghe needs no introduction. As the Minister of Sports, he plucked up the courage to take on the politically-backed powerful cricket Mafia with international links, only to be hounded out of his ministerial post. The dark forces responsible for his ouster from the Cabinet may have thought they would be able to silence him, but he has proved that he is made of sterner stuff. He has emerged stronger, and is working hard to mobilise the public against the corrupt government leaders and their cronies.

Ranasinghe has launched an anti-corruption movement with a political goal—the Stop Corruption, Build Motherland (SCBM) alliance––and invited all those who want Sri Lanka to be rid of corruption to sink their political differences and join forces to achieve national progress.

What made Ranasinghe to pit himself against the cricket Mafia and what are his future plans? The Island met him recently. Excerpts of our freewheeling interview with him:

Q: Tell us about your background?

I am Ranasinghe Arachchige Roshan Anuruddha. My father’s family, hailing from the South, settled down in Nugawela, Kandy. My paternal grandfather had a home in Harispaththuwa and my paternal grandmother was from Kumbukgete, Kurunegala. My father was the only child in his family. My mother’s father was from Weligama. As such, I have roots in four districts!

Both my maternal and paternal families were staunch UNP supporters. They backed D. S. Senanayake and his vision. My father was close to the late Mr. Gamini Dissanayake. As a result of his politics, we lost our house. My mother had the courage to start life anew from scratch. She worked hard to improve our situation. My sister became a doctor and my two brothers took to accountancy. As soon as I completed my GCE A/L, I wanted to go to Japan.

My brothers were in France at that time. They advised me to visit them first and obtain a resident visa there. In France, I pursued my education, but I couldn’t complete it because I was determined to fulfill my dream of going to Japan. Initially, I went to Japan with a tourist visa. I travelled to many places in Japan and observed the situation in each place. Later, I went to Japan again on a student visa, and studied and worked part-time. I obtained a Diploma in Business Administration and Automobiles. I believe I learned more from Japanese society than from the theories taught in class. That education has served me well in my career as a businessman in several countries and also stood me in good stead in my political activities.

In 1996, my mother passed away, at the age of 49. I was 20 at the time, and her death was a great loss to me. After some time, I met a Sri Lankan girl in Japan. Our friendship developed into a relationship, and she is now my wife. We got married in 1999. Her name is Prashanthi Dinusha Ranasinghe, and she is a lawyer. She has been my strongest support, helping me build my businesses and supporting me in my political endeavours. I have attended four schools: Rajangana Maha Vidyalaya because our businesses were in Rajanganaya, Vidyartha College Kandy, Thambuttegama Central College, and Polonnaruwa Royal College.

Q: What kind of business are you engaged in?

I established my businesses in Japan, the UK, Mozambique, South Africa, and Sri Lanka. In these five countries, I import and sell vehicles, automobile spare parts, and high-end wrist-watches.

Q: When did you take to active politics?

I began my political career in 2009 after receiving invitations from both Ranil Wickremesinghe and Mahinda Rajapaksa. Upon receiving Wickremesinghe’s invitation, I expressed my willingness to contest from Polonnaruwa. He assured me of that opportunity. Later, I received another invitation from Mahinda Rajapaksa. I informed him that I had already given my word to Wickremesinghe and would contest from Polonnaruwa.

Subsequently, Wickremesinghe informed me that Earl Gunasekera did not want me to contest from Polonnaruwa and suggested I contest from Laggala instead. I insisted that I be allowed to contest from Polonnaruwa, and informed Wickremesinghe of Rajapaksa’s offer to contest under the UPFA ticket from the same district. Wickremesinghe wished me good luck, and I joined the UPFA as a district organizer for Polonnaruwa. Other candidates in the same team were electoral organizers who had already secured 40,000 preferential votes, while I had none. Some encouraged me, while others discouraged me.

I was elected with the highest number of preferential votes in the district. Maithripala Sirisena was the district leader, and I respected his leadership while focusing on my responsibilities. Over the next three years, I received no assistance from the party to develop the district. Basil Rajapaksa informed me that he couldn’t allocate funds due to opposition from Maithripala Sirisena. But with the assistance of well-wishers and friends, I did everything possible to serve the people of Polonnaruwa. We constructed roads, generated employment opportunities for the unemployed, and introduced technology to Polonnaruwa.

Q: What made the relationship between you and Maithripala Sirisena turn sour?

When Maithripala Sirisena left the SLFP, he carried with him all the grassroots organizations of the party in Polonnaruwa. Siripala Gamlath and Chandrasiri Sooriyiarachchi remained silent. I was tasked with organizing the presidential campaign in the Polonnaruwa District, which presented one of the biggest challenges I’ve ever faced as a district leader. I was pitted against heavyweight Maithripala Sirisena in that district. However, I enabled the party to perform better in Polonnaruwa than in the Hambantota District. Rajapaksa, as the presidential candidate, secured over 70 percent of the total district votes in his home district, Hambantota, but due to our efforts, Sirisena could poll only 55% of the votes in his home district, Polonnaruwa.

After his victory, Sirisena invited me for talks and had others file a case against me in the High Court of Polonnaruwa, accusing me of attempted murder. As the case is pending, I won’t discuss it further.

During our talks, Sirisena asked whether I would join him and go to heaven or remained loyal to Mahinda Rajapaksa and go to hell. He suggested that if I joined him, the case against me would be dropped, and he would instruct all grassroots party leaders to work with me. However, I told him that there were policy differences that prevented me from joining him.

In the 2018 local government elections, I was put in charge of the SLPP’s Polonnaruwa District campaign. It pitted myself against President Sirisena. Despite his executive powers and support from the then Prime Minister Ranil Wickremesinghe, the people voted for us. We defeated both the UNP and the SLFP.

Q: Don’t you think the Rajapaksas used you and let you down?

I have remained undefeated in elections, and after the SLPP’s victory at the 2020 general election, Mahinda Rajapaksa and Gotabaya Rajapaksa came to Polonnaruwa and said that I would be given a Cabinet portfolio so that I could launch some development projects in the district. However, I was given a State Minister post. I was tasked with helping young entrepreneurs. While I was progressing in that project, I was shifted to the Provincial Councils and Local Government State Ministry.

During the pandemic, I worked with all 330 councils. When the farmers’ crisis came up, I was appointed Mahaweli State Minister. Likewise, I was given three different state ministries within that short period of time. When the fertiliser crisis cropped up, I resigned not only from the ministerial posts but also from the Pohottuwa District leadership. Thereafter, I remained an independent MP. We witnessed massive opposition against those who remained in ministerial posts of the Pohottuwa government.

Then came the Aragalaya protests. President Wickremesinghe invited me to accept responsibilities to work with him and offered four powerful ministries – Sports, Youth Affairs, Mahaweli, and Irrigation. None of those ministries had funds at the time I accepted them. I had been handling the affairs of these ministries successfully when I was shown the door for trying to rid cricket administration of corruption.

Q: Some sports bodies faced bans under your watch. Why?

Rugby was already facing a ban when I assumed duties as the Sports Minister. There was a problem between the Rugby Chairman and the Asian Council. The latter did not recognize the former, so they banned Sri Lankan Rugby. The Chairman was adamant about staying in his post. I requested him to resign for the sake of the country because the Asian Council was ready to lift the ban if he stepped down.

I had to appoint an interim body to control the game. The Chairman then went to courts, where he later expressed his willingness to resign. With his resignation, the Asian Council lifted the ban.

Q: What about the ban on the Football Association?

The football administration is a metaphor for corruption. FIFA had been asking for reforms to the Football Association’s constitution since 2014. Their main demand was to remove football administration from the current national sports law and grant it autonomy. As their demands were not met, FIFA banned Sri Lanka.

I met FIFA General Secretary Fatma Samoura and explained the situation. They agreed to change their stance to allow the football governing body to operate within the framework of national sports laws. They gave us four years to implement this. They wanted us to make it mandatory for football officials to retire at the age of 70. I myself would retire from politics when I reach 65 years. We must let the youth come up.

Q: Your efforts to cleanse the cricket administration backfired. How would you look back at what happened?

Regarding cricket control, the entire nation knows the truth. The ICC ban on Sri Lanka cricket was orchestrated. It was officials who got the ban imposed, and it was they who got it lifted.

I have no problem with J. Sha. He is a citizen of another country. Sha was used as a shield by Sri Lanka Cricket officials, who were exposed for corruption by the Auditor General. He was misused. I was against it. When I assumed the office, I told those officials that I would not mind what happened in the past and they must be ready to work without any such deals hereafter. In that context, we won a one-day series against Australia, a test series against Pakistan, and we won the Asian Cup. Thereafter, those officials got close to the President, and had me ousted. Sri Lanka’s cricket has been the loser.

Q: You say you are a campaigner against corruption. We have had several Bodhisatvas recently in this country. Aren’t you playing the role of messiah against corruption to further self-interest in politics? When you joined hands with the Rajapaksas, you knew they were corrupt. How would you reconcile your battle against corruption and your association with the Rajapaksas in the past?

I never whitewashed the Rajapaksas. I had no such need. I needed to start somewhere when I decided to take to politics and at that time the Rajapaksas had popular support. Even the JVP supported Mahinda Rajapaksa in 2005. I believe they did so with good intentions, just as I did. We thought that they would do something for the country.

Q: But you continued to back the Rajapaksas even after they were exposed for corruption and various other malpractices. You did not leave them in 2015, when some SLFP stalwarts decamp. What would you say to this?

In 2015, there were some issues, such as nepotism and corruption. But we had to remain there because the alternative to the Rajapaksas was a messy alliance forged by Sirisena and Wickremesinghe. We feared that a country would be plunged into anarchy. We hoped that the Rajapaksas would mend their ways by the end of the Yahapalana government, which was responsible for the Treasury bond scams and failure to prevent the Easter Sunday terror attacks.

While we were planning to bring Gotabaya to power, nobody thought that he would promote family rule. But when we realized that we had made a mistake, we distanced ourselves from the government.

What we need is a righteous leader instead of a person who promotes family bandyism, protects corrupt officials, and indulges in corruption. We have become a bankrupt nation. We are against corruption. Talking about rebuilding this nation without putting an end to corruption is only a pipedream.

Q: You have launched a political movement to eliminate corruption. How would you describe it?

We are forming an alliance under the theme, ‘Let’s put an end to corruption to build our nation.’

There is a pressing need for a formidable force against corruption. We cannot think of a better future unless we go all out to get rid of corruption.

I will give you one example: when I assumed the Ministry of Sports, it did not have money. The country was bankrupt, and the government’s allocation barely sufficed to pay salaries. We ran the Ministry with funds from sponsorships. Nevertheless, during my tenure, this country won the highest number of international medals. Under the watch of SB Dissanayake, the country secured 58 international medals and that was the time when the Sports Ministry had enough funds. I inherited the same Ministry full of crises, and stopped corruption, and the result was really impressive; the country bagged 170 medals in international games.

This shows that when corruption is eliminated, progress follows.

Q: How do you propose to battle corruption and enlist popular support for that endeavour?

We have formed an alliance against corruption and rebuilding the nation. There are many individuals against corruption across the political spectrum, including politicians representing Parliament, as well as those outside Parliament. Anyone who is against corruption and has not engaged in any corrupt activities, can join this alliance.

We have appointed a committee to identify the corrupt, starting with the MPs. Sri Lanka Cricket officials have been exposed by the Auditor General for their corrupt deals, but there are still some MPs who unashamedly support those corrupt elements. They have direct links with the corrupt.

Under the anti-corruption committee, there will be sub-committees tasked with ascertaining the views of the public about corruption and how to battle it.We have a retired Supreme Court Judge, a retired High Court Judge, three lawyers, doctors, engineers, economists, and auditors on the steering committee. They work on a voluntary basis. I will not name them for obvious reasons.

Q: Does it mean that this committee will name the clean politicians and will label the rest as corrupt? How practical is that?

The committee will clear the names, and after that, we will extend invitations. It is up to each of those MPs with clear profiles to either join us or not.

Q: Aren’t you planning to turn the anti-corruption movement into a political force?

To eliminate corruption, we need state power, which we can achieve only by winning elections. We will have to form a party so that people against corruption can vote for it and make a contribution towards ridding the country of corruption.

There is no alternative. This country is in crisis. Our economy has collapsed. The crisis has not prevented the ruling party politicians from enriching themselves at the expense of the public. We must change this system and for that purpose we need power.

Q: The country already has about 80 political parties. Won’t the party you are planning to form end up being another name board?

The main parties are facing disintegration. The SLFP, the SLPP and the UNP are faction ridden. Sri Lankans have realized the need for a change. There is space for a new political force on a mission to eliminate corruption.

Q: Many have predicted that there would be a hung Parliament after the next general election. Supposing your party, which is to be formed, will obtain a substantial number of seats, will it join forces with one or some of the parties that you consider corrupt?

No, that will never happen. Never will we join hands with the corrupt. I believe that the existing political culture has to be changed. Even if we are in the Opposition, we must support a government when it does something right. We must do away with our traditional political approach where the Opposition is always expected to stand against whatever the government does, whether it is right or wrong.

SJB MP Imtiaz Bakeer Markar recently proposed that we allocate 25 percent of seats to young MPs. It is a good proposal, and I agreed with him. During the Sri Lanka Cricket issue, Opposition Leader Sajith Premadasa stood by me, and he did it for the sake of the country. We should appreciate his stance.

Q: Many youths have left the country, and some others are planning to migrate. This will adversely impact the country’s development efforts and future. What plans do your movement have to address this problem?

Most of those who are migrating are from the SME sector, which collapsed because of loans. We asked other nations to reschedule the loans we had taken. The government got local banks to reschedule the loans they had given to the government. But nothing was done to reschedule the loans obtained by the SMEs.

The government is not there to construct culverts and gutters. The government is there to protect people in crisis. Those in the SME sector spent their 24 hours thinking about how to pay back the loans. They have no time to think about how to develop their enterprises. Sri Lanka has received USD 400 million from the Asian Development Bank, USD 300 million from the World Bank, besides IMF assistance.

These funds must be utilized to develop entrepreneurs. Concessions should be given to entrepreneurs. Just because we ask, the youth would not stop leaving the country. We must unveil a plan to ensure a secure future for them. The youth are more conscious of their rights and freedoms and more averse to corruption than others. That is why they took to the streets. If we can convince them that the country will be rid of corruption and a viable programme is underway to develop the economy and improve the people’s lot, they will not leave this country. That is what we are striving to do.

Features

Counting cats, naming giants: Inside the unofficial science redefining Sri Lanka’s Leopards and Tuskers

For decades, Sri Lanka’s leopard numbers have been debated, estimated, and contested, often based on assumptions few outside academic circles ever questioned.

One of the most fundamental was that a leopard’s spots never change. That belief, long accepted as scientific fact, began to unravel not in a laboratory or lecture hall, but through thousands of photographs taken patiently in the wilds of Yala. At the centre of that quiet disruption stands Milinda Wattegedara.

Sri Lanka’s wilderness has always inspired photographers. Far fewer, however, have transformed photography into a data-driven challenge to established conservation science. Wattegedara—an MBA graduate by training and a wildlife researcher by pursuit—has done precisely that, building one of the most comprehensive independent identification databases of leopards and tuskers in the country.

“I consider myself privileged to have been born and raised in Sri Lanka,” Wattegedara says. “This island is extraordinary in its biodiversity. But admiration alone doesn’t protect wildlife. Accuracy does.”

Raised in Kandy, and educated at Kingswood College, where he captained cricket teams, up to the First XI, Wattegedara’s early years were shaped by discipline and long hours of practice—traits that would later define his approach to field research.

Though his formal education culminated in a Master’s degree in Business Administration from Cardiff Metropolitan University, his professional life gradually shifted toward Sri Lanka’s forests, grasslands, and coastal fringes.

From childhood, two species held his attention: the Sri Lankan leopard and the Asian elephant tusker. Both are icons. Both are elusive. And both, he argues, have been inadequately understood.

His response was methodical. Using high-resolution photography, Wattegedara began documenting individual animals, focusing on repeat sightings, behavioural traits, territorial ranges, and physical markers.

This effort formalised into two platforms—Yala Leopard Diary and Wild Tuskers of Sri Lanka—which function today as tightly moderated research communities rather than casual social media pages.

“My goal was never popularity,” he explains. “It was reliability. Every identification had to stand scrutiny.”

The results are difficult to dismiss. Through collaborative verification and long-term monitoring, his teams have identified over 200 individual leopards across Yala and Kumana National Parks and 280 tuskers across Sri Lanka.

Each animal—whether Jessica YF52 patrolling Mahaseelawa beach or Mahasen T037, the longest tusker bearer recorded in the wild—is catalogued with photographic evidence and movement history.

It was within this growing body of data that a critical inconsistency emerged.

“As injuries accumulated over time, we noticed subtle but consistent changes in rosette and spot patterns,” Wattegedara says. “This directly contradicted the assumption that these markings remain unchanged for life.”

That observation, later corroborated through structured analysis, had serious implications. If leopards were being identified using a limited set of spot references, population estimates risked duplication and inflation.

The findings led to the development of the Multipoint Leopard Identification Method, now internationally published, which uses multiple reference points rather than fixed pattern assumptions. “This wasn’t about academic debate,” Wattegedara notes. “It was about ensuring we weren’t miscounting an endangered species.”

The implications extend beyond Sri Lanka. Overestimated populations can lead to reduced protection, misplaced policy decisions, and weakened conservation urgency.

Yet much of this work has occurred outside formal state institutions.

“There’s a misconception that meaningful research only comes from official channels,” Wattegedara says. “But conservation gaps don’t wait for bureaucracy.”

That philosophy informed his role as co-founder of the Yala Leopard Centre, the world’s first facility dedicated solely to leopard education and identification. The Centre serves as a bridge between researchers, wildlife enthusiasts, and the general public, offering access to verified knowledge rather than speculation.

In a further step toward transparency, Artificial Intelligence has been introduced for automatic leopard identification, freely accessible via the Centre and the Yala Leopard Diary website. “Technology allows consistency,” he explains. “And consistency is everything in long-term studies.”

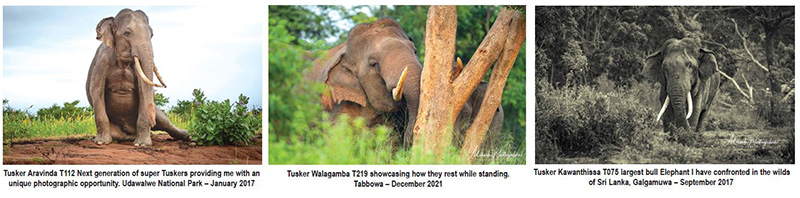

His work with tuskers mirrors the same precision. From Minneriya to Galgamuwa, Udawalawe to Kala Wewa, Wattegedara has documented generations of bull elephants—Arjuna T008, Kawanthissa T075, Aravinda T112—not merely as photographic subjects, but as individuals with lineage, temperament, and territory.

This depth of observation has also earned him recognition in wildlife photography, including top honours from the Photographic Society of Sri Lanka and accolades from Sanctuary Asia’s Call of the Wild. Still, he is quick to downplay awards.

“Photographs are only valuable if they contribute to understanding,” he says.

Today, Wattegedara’s co-authored identification guides on Yala leopards and Kala Wewa tuskers are increasingly referenced by researchers and field naturalists alike. His work challenges a long-standing divide between citizen science and formal research.

“Wildlife doesn’t care who publishes first,” he reflects. “It only responds to how accurately we observe it.”

In an era when Sri Lanka’s protected areas face mounting pressure—from tourism, infrastructure, and climate stress—the question of who counts wildlife, and how, has never been more urgent.

By insisting on precision, patience, and proof, Milinda Wattegedara has quietly reframed that conversation—one leopard, one tusker, and one verified photograph at a time.

By Ifham Nizam ✍️

Features

AI in Schools: Preparing the Nation for the Next Technological Leap

This summary document is based on an exemplary webinar conducted by the Bandaranaike Academy for Leadership & Public Policy ((https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=TqZGjlaMC08). I participated in the session, which featured multiple speakers with exceptional knowledge and experience who discussed various aspects of incorporating artificial intelligence (AI) into the education system and other sectors.

There was strong consensus that this issue must be addressed early, before the nation becomes vulnerable to external actors seeking to exploit AI for their own advantage. Given her educational background, the Education Minister—and the Prime Minister—are likely to be fully aware of this need. This article is intended to support ongoing efforts in educational reform, including the introduction of AI education in schools for those institutions willing to adopt it.

Artificial intelligence is no longer a futuristic concept. Today, it processes vast amounts of global data and makes calculated decisions, often to the benefit of its creators. However, most users remain unaware of the information AI gathers or the extent of its influence on decision-making. Experts warn that without informed and responsible use, nations risk becoming increasingly vulnerable to external forces that may exploit AI.

The Need for Immediate Action

AI is evolving rapidly, leaving traditional educational models struggling to keep pace. By the time new curricula are finalised, they risk becoming outdated, leaving both students and teachers behind. Experts advocate immediate government-led initiatives, including pilot AI education programs in willing schools and nationwide teacher training.

“AI is already with us,” experts note. “We must ensure our nation is on this ‘AI bus’—unlike past technological revolutions, such as IT, microchips, and nanotechnology, which we were slow to embrace.”

Training Teachers and Students

Equipping teachers to introduce AI, at least at the secondary school level, is a crucial first step. AI can enhance creativity, summarise materials, generate lesson plans, provide personalised learning experiences, and even support administrative tasks. Our neighbouring country, India, has already begun this process.

Current data show that student use of AI far exceeds that of instructors—a gap that must be addressed to prevent misuse and educational malpractice. Specialists recommend piloting AI courses as electives, gathering feedback, and continuously refining the curriculum to prepare students for an AI-driven future.

Benefits of AI in Education

AI in schools offers numerous advantages:

· Fosters critical thinking, creativity, and problem-solving skills

· Enhances digital literacy and ethical awareness

· Bridges the digital divide by promoting equitable AI literacy

· Supports interdisciplinary learning in medicine, climate science, and linguistics

· Provides personalised feedback and learning experiences

· Assists students with disabilities through adaptive technologies like text-to-speech and visual recognition

AI can also automate administrative tasks, freeing teachers to focus on student engagement and social-emotional development—a key factor in academic success.

Risks and Challenges

Despite its potential, AI presents challenges:

· Data privacy concerns and misuse of personal information

· Over-reliance on technology, reducing teacher-student interactions

· Algorithmic biases affecting educational outcomes

· Increased opportunities for academic dishonesty if assessments rely on rote memorisation

Experts emphasise understanding these risks to ensure the responsible and ethical use of AI.

Global and Local Perspectives

In India, the Central Board of Secondary Education plans to introduce AI and computational thinking from Grades 3 to 12 by 2026. Sri Lanka faces a similar challenge. Many university students and academics already rely on AI, highlighting the urgent need for a structured yet rapidly evolving national curriculum that incorporates AI responsibly.

The Way Forward

Experts urge swift action:

· Launch pilot programs in select schools immediately.

· Provide teacher training and seed funding to participating educational institutions.

· Engage universities to develop short AI and innovation training programs.

“Waiting for others to lead risks leaving us behind,” experts warn. “It’s time to embrace AI thoughtfully, responsibly, and inclusively—ensuring the whole nation benefits from its opportunities.”

As AI reshapes our world, introducing it in schools is not merely an educational initiative—it is a national imperative.

BY Chula Goonasekera ✍️

on behalf of LEADS forum admin@srilankaleads.com

Features

The Paradox of Trump Power: Contested Authoritarian at Home, Uncontested Bully Abroad

The Trump paradox is easily explained at one level. The US President unleashes American superpower and tariff power abroad with impunity and without contestation. But he cannot exercise unconstitutional executive power including tariff power without checks and challenges within America. No American President after World War II has exercised his authority overseas so brazenly and without any congressional referral as Donald Trump is getting accustomed to doing now. And no American President in history has benefited from a pliant Congress and an equally pliant Supreme Court as has Donald Trump in his second term as president.

Yet he is not having his way in his own country the way he is bullying around the world. People are out on the streets protesting against the wannabe king. This week’s killing of 37 year old Renee Good by immigration agents in Minneapolis has brought the City to its edge five years after the police killing of George Floyd. The lower courts are checking the president relentlessly in spite of the Supreme Court, if not in defiance of it. There are cracks in the Trump’s MAGA world, disillusioned by his neglect of the economy and his costly distractions overseas. His ratings are slowly but surely falling. And in an electoral harbinger, New York has elected as its new mayor, Zoran Mamdani – a wholesale antithesis of Donald Trump you can ever find.

Outside America it is a different picture. The world is too divided and too cautious to stand up to Trump as he recklessly dismantles the very world order that his predecessors have been assiduously imposing on the world for nearly a hundred years. A few recent events dramatically illustrate the Trump paradox – his constraints at home and his freewheeling abroad.

Restive America

Two days before Christmas, the US Supreme Court delivered a rare rebuke to the Trump Administration. After a host of rulings that favoured Trump by putting on hold, without full hearing, lower court strictures against the Administration, the Supreme Court by a 6-3 majority decided to leave in place a Federal Court ruling that barred Trump from deploying National Guard troops in Chicago. Trump quietly raised the white flag and before Christmas withdrew the federal troops he had controversially deployed in Chicago, Portland and Los Angeles – all large cities run by Democrats.

But three days after the New Year, Trump airlifted the might of the US Army to encircle Venezuela’s capital Caracas and spirit away the country’s President Nicolás Maduro, and his wife Celia Flores, all the way to New York to stand trial in an American Court. What is not permissible in any American City was carried out with absolute impunity in a foreign capital. It turns out the Administration has no plan for Venezuela after taking out Maduro, other than Trump’s cavalier assertion, “We’re going to run it, essentially.” Essentially, the Trump Administration has let Maduro’s regime without Maduro to run the country but with the US in total control of Venezuela’s oil.

Next on the brazen list is Greenland, and Secretary of State Marco Rubio who manipulated Maduro’s ouster is off to Copenhagen for discussions with the Danish government over the future of Greenland, a semi-autonomous part of Denmark. Military option is not off the table if a simple real estate purchase or a treaty arrangement were to prove infeasible or too complicated. That is the American position as it is now customarily announced from the White House podium by the Administration’s Press Secretary Karolyn Leavitt, a 28 year old Catholic woman from New Hampshire, who reportedly conducts a team prayer for divine help before appearing at the lectern to lecture.

After the Supreme Court ruling and the Venezuela adventure, the third US development relevant to my argument is the shooting and killing of a 37 year old white American woman by a US Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) officer in Minneapolis, at 9:30 in the morning, Wednesday, January 7th. Immediately, the Administration went into pre-emptive attack mode calling the victim a “deranged leftist” and a “domestic terrorist,” and asserting that the ICE officer was acting in self-defense. That line and the description are contrary to what many people know of the victim, as well as what people saw and captured on their phones and cameras.

The victim, Renee Nicole Good, was a mother of three and a prize-winning poet who self-described herself a “poet, writer, wife and mom.” A newcomer to Minneapolis from Colorado, she was active in the community and was a designated “legal observer of Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) activities,” to monitor interactions between ICE agents and civilian protesters that have become the norm in large immigrant cities in America. Renee Good was at the scene in her vehicle to observe ICE operations and community protesters.

In video postings that last a matter of nine seconds, two ICE officers are seen approaching Good’s vehicle and one of them trying to open her door; a bystander is heard screaming “No” as Good is seen trying to drive away; and a third ICE officer is seen standing in front of her moving vehicle, firing twice in the direction of the driver, moving to a side and firing a third time from the side. Good’s car is seen going out of control, careening and coming to a stop on a snowbank. Yet America is being bombarded with two irreconcilable narratives – one manufactured by Trump’s Administration and the other by those at the scene and everyone opposed to the regime.

It adds to the explosiveness of the situation that Good was shot and killed not far from where George Folyd was killed, also in Minneapolis, on 25th May, 2020, choked under the knee of a heartless policeman. And within 48 hours of Good’s killing, two Americans were shot and injured by two federal immigration agents, in Portland, Oregon, on the Westcoast. Trump’s attack on immigrants and the highhanded methods used by ICE agents have become the biggest flashpoint in the political opposition to the Trump presidency. People are organizing protests in places where ICE agents are apprehending immigrants because those who are being aggressively and violently apprehended have long been neighbours, colleagues, small business owners and students in their communities.

Deportation of illegal immigrants is not something that began under Trump. It has been going on in large numbers under all recent presidents including Obama and Biden. But it has never been so cruel and vicious as it is now under Trump. He has turned it into a television spectacle and hired large number of new ICE agents who are politically prejudiced and deployed them without proper training. They raid private homes and public buildings, including schools, looking for immigrants. When faced with protesters they get into clashes rather than deescalating the situation as professional police are trained to do. There is also the fear that the Administration may want to escalate confrontations with protesters to create a pretext for declaring martial law and disrupt the midterm congressional elections in November this year.

But the momentum that Trump was enjoying when he began his second term and started imposing his executive authority, has all but vanished and all within just one year in office. By the time this piece appears in print, the Supreme Court ruling on Trump’s tariffs (expected on Friday) may be out, and if as expected the ruling goes against Trump that will be a massive body blow to the Administration. Trump will of course use a negative court ruling as the reason for all the economic woes under his presidency, but by then even more Americans would have become tired of his perpetually recycled lies and boasts.

An Obliging World

To get back to my starting argument, it is in this increasingly hostile domestic backdrop that Trump has started looking abroad to assert his power without facing any resistance. And the world is obliging. The western leaders in Europe, Canada and Australia are like the three wise monkeys who will see no evil, hear no evil and speak no evil – of anything that Trump does or fails to do. Their biggest fear is about the Trump tariffs – that if they say anything critical of Trump he will magnify the tariffs against their exports to the US. That is an understandable concern and it would be interesting to see if anything will change if the US Supreme Court were to rule against Trump and reject his tariff powers.

Outside the West, and with the exception of China, there is no other country that can stand up to Trump’s bullying and erratic wielding of power. They are also not in a position to oppose Trump and face increased tariffs on their exports to the US. Putin is in his own space and appears to be assured that Trump will not hurt him for whatever reason – and there are many of them, real and speculative. The case of the Latin American countries is different as they are part of the Western Hemisphere, where Trump believes he is monarch of all he surveys.

After more than a hundred years of despising America, many communities, not just regimes, in the region seem to be warming up to Trump. The timing of Trump’s sequestering of Venezuela is coinciding with a rising right wing wave and regime change in the region. An October opinion poll showed 53% of Latin American respondents reacting positively to a then potential US intervention in Venezuela while only 18% of US respondents were in favour of intervention. While there were condemnations by Latin American left leaders, seven Latin American countries with right wing governments gave full throated support to Trump’s ouster of Maduro.

The reasons are not difficult to see. The spread of crime induced by the commerce of cocaine has become the number one concern for most Latin Americans. The socio-religious backdrop to this is the evangelisation of Christianity at the expense of the traditional Catholic Church throughout Latin America. And taking a leaf from Trump, Latin Americans have also embraced the bogey of immigration, mainly influenced by the influx of Venezuelans fleeing in large numbers to escape the horrors of the Maduro regime.

But the current changes in Latin America are not necessarily indicative of a durable ideological shift. The traditional left’s base in the subcontinent is still robust and the recent regime changes are perhaps more due to incumbency fatigue than shifts in political orientations. The left has been in power for the greater part of this century and has not been able to provide answers to the real questions that preoccupied the people – economic affordability, crime and cocaine. It has not been electorally smart for the left to ignore the basic questions of the people and focus on grand projects for the intelligentsia. Exhibit #1 is the grand constitutional project in Chile under outgoing President Gabriel Borich, but it is not the only one. More romantic than realistic, Boric’s project titillated liberal constitutionalists the world over, but was roundly rejected by Chileans.

More importantly, and sooner than later, Trump’s intervention in Venezuela and his intended takeover of the country’s oil business will produce lasting backlashes, once the initial right wing euphoria starts subsiding. Apart from the bully force of Trump’s personality, the mastermind behind the intervention in Venezuela and policy approach towards Latin America in general, is Secretary of State Marco Rubio, the former Cuban American Senator from Florida and the principal leader of the group of Cuban neocons in the US. His ultimate objective is said to be achieving regime change in Cuba – apparently a psychological settling of scores on behalf Cuban Americans who have been dead set against Castro’s Cuba after the overthrow of their beloved Batista.

Mr. Rubio is American born and his parents had left Cuba years before Fidel Castro displaced Fulgencio Batista, but the family stories he apparently grew up hearing in Florida have been a large part of his self-acknowledged political makeup. Even so, Secretary Rubio could never have foreseen a situation such as an externally uncontested Trump presidency in which he would be able to play an exceptionally influential role in shaping American policy for Latin America. But as the old Burns’ poem rhymes, “The best-laid plans of men and mice often go awry.”

by Rajan Philips ✍️

-

News1 day ago

News1 day agoSajith: Ashoka Chakra replaces Dharmachakra in Buddhism textbook

-

Business1 day ago

Business1 day agoDialog and UnionPay International Join Forces to Elevate Sri Lanka’s Digital Payment Landscape

-

Features1 day ago

Features1 day agoThe Paradox of Trump Power: Contested Authoritarian at Home, Uncontested Bully Abroad

-

News6 days ago

News6 days agoInterception of SL fishing craft by Seychelles: Trawler owners demand international investigation

-

News1 day ago

News1 day agoLevel I landslide early warnings issued to the Districts of Badulla, Kandy, Matale and Nuwara-Eliya extended

-

Features1 day ago

Features1 day agoSubject:Whatever happened to (my) three million dollars?

-

News6 days ago

News6 days agoBroad support emerges for Faiszer’s sweeping proposals on long- delayed divorce and personal law reforms

-

News1 day ago

News1 day ago65 withdrawn cases re-filed by Govt, PM tells Parliament