Midweek Review

Alborada: Dawn Song or Dawn Rape?

By Carmen Wickramagamage

Ashoka Handagama’s latest film, Alborada, introduces itself as “the poem that Neruda never wrote.” What is this poem? Released on February 14 to coincide with Valentine’s Day, the irony of the timing is hard to miss for Alborada culminates in the horrific rape by Neruda, the great love poet, of a female latrine cleaner during his brief stay in Ceylon as the Chilean Consul. Hardly a subject that lends itself to poetry though the recitations in the film, in the original Spanish, of poems that Neruda did write are mesmerizing. Perhaps this explains why Garcia Marquez chose to characterize Neruda as “the greatest poet of the twentieth century in any language”. What is Handagama’s intention in the film?

In interviews, Handagama has spoken of his film as a challenge to Western hegemony that he claims operated to push this ignominious act under the carpet. But he has made it clear that unearthing a little-known fact about a poet hailed today as a critic of capitalism and champion of the oppressed is not his only intention. He sees his film as making an intervention into the contemporary discourse on women’s right to bodily autonomy in the age of #MeToo. Handagama is clearly well-intentioned. It is therefore necessary to examine how Alborada intervenes, through its representation of the scene of rape, in the rape culture that naturalizes masculine privilege and feminine vulnerability.

Source of the story

The source of what we know about the incident is Neruda himself. While he may not have composed a poem about the rape, he did “confess” to it in his memoirs translated into English by Hadley St. Martin as I confess I have lived: memoirs (1977). Written some forty years later, one page of the eleven pages (out of three-hundred fifty) that he devotes to his Ceylonese sojourn concerns itself with this incident. Though it created hardly a ripple in Sri Lanka, in Chile, Neruda’s admission stirred up a storm when the Chilean Parliament voted in 2018 to rename the airport in Santiago after him, with women and human rights activists vociferously protesting against the plan citing this incident. Not that the incident was completely unknown in Sri Lanka but the rumour that was doing the rounds was more along the lines of “something” between Neruda and his “domestic”. Handagama has said that he first read about it in a book by Tissa Abeysekera which, according to Sarath Chandrajeewa, went this way: “the great poet, the Nobel prize winner who loved a scavenger woman in Wellawatte”. No mention of rape there. Transferring a brief reference in Neruda’s memoirs into film and making it the pièce de résistance of a visually powerful medium is a radical gesture but how radical is it in its contribution to the ongoing conversation on rape?

Handagama has tried to distance himself from Neruda, calling the film his “creation” just as Neruda’s memoirs were his but the film is in large measure faithful to Neruda’s recollections of his stay in Ceylon, highlighting the theme of solitude that runs like a refrain through the young poet’s account and offering a sympathetic portrait of a man ill at ease in the “narrow colonialism” of the British but intrigued by the sights, sounds and people of Ceylon. Just as Neruda is the subject of his memoirs, so is he in the film. In only one respect is there a significant deviation: the representation of rape.

The Incident

In Neruda’s account, his interest in the woman begins with his curiosity about the mysterious workings of his latrine. When he finally sees the woman who cleans it, he is not repulsed, calling her instead the “the most beautiful woman I had yet seen in Ceylon” (p. 99) and elevating her above the rest through appellations such as “queen” and goddess”. But, when she disdains his tokens of love in the form of silks and fruits, he exercises his white male prerogative over native women’s bodies by raping her: “One morning , I decided to go all the way. I got a strong grip on her wrist and stared into her eyes. There was no language I could talk with her. Unsmiling, she let herself be led away and was soon naked in my bed. Her waist, so very slim, her full hips, the brimming cups of her breasts made her like one of the thousand-year-old sculptures from the south of India. It was the coming together of a man and a statue” (p. 100).

In Neruda’s account, his interest in the woman begins with his curiosity about the mysterious workings of his latrine. When he finally sees the woman who cleans it, he is not repulsed, calling her instead the “the most beautiful woman I had yet seen in Ceylon” (p. 99) and elevating her above the rest through appellations such as “queen” and goddess”. But, when she disdains his tokens of love in the form of silks and fruits, he exercises his white male prerogative over native women’s bodies by raping her: “One morning , I decided to go all the way. I got a strong grip on her wrist and stared into her eyes. There was no language I could talk with her. Unsmiling, she let herself be led away and was soon naked in my bed. Her waist, so very slim, her full hips, the brimming cups of her breasts made her like one of the thousand-year-old sculptures from the south of India. It was the coming together of a man and a statue” (p. 100).

Neruda plays down the violence of the encounter in his penitential recounting, resorting instead to euphemisms. The woman does not struggle. She “let herself be led” (Is she deterred by the “strong grip on her wrist”?). She does not scream for help (Is she aware of its futility given the isolated location of the bungalow?). She was “soon naked”, how she came to be naked elided, its place taken by an aestheticized description of the female form reminiscent of classical Sanskrit poetry that deflects attention from the violence. Some trace of the woman’s resistance is acknowledged in her unresponsiveness. At the climactic moment, when he forces himself on her, she turns into a sculpture in his eyes, turning Neruda in turn into a Pygmalion in reverse. Where Pygmalion (in Ovid’s Metamorphosis) manages to obtain his heart’s desire by turning a statue (thanks to Venus’ intervention) into the woman of his dreams, Neruda’s touch turns a living, breathing woman into a sculpture. The description ends with lines that have self-loathing write large over it: “She was right to despise me . The experience was never repeated” (p. 100).

Its Representation

How does Handagama render this incident in film? Unlike in the memoirs, here, the audience is prepped from the start for the impending climax through the sighting of the Parvati statue by Neruda on arrival, his frolics with members of the Sakkili community that has Ratné Aiya incensed, and the rhythmic chiming of the latrine-cleaner’s anklets that wakes him up at dawn from a night of love-making. When the rape finally occurs, it is portrayed on screen in all its brutality. The woman screams, she struggles valiantly to escape, she has to be forcibly detained and stripped naked before the final humiliation of rape. There is nothing subtle or indirect about it. Why this directorial decision to deviate? Is it that Handagama wanted to dispel any illusions that his audience may entertain about the great poet Neruda? Or did he want to force his audience to confront head on the brutality of rape against the backdrop of a rape culture that thrives on misconceptions regarding women’s consent?

I find Handagama’s directorial decisions problematic on many fronts. For one thing, in the eyes of the law, ‘rape’ is sexual intercourse without consent, what constitutes “absence of consent” carefully delineated to accommodate the different scenarios that qualify as “rape” in the eyes of the law. Here, the woman violently struggles, thus confirming a misunderstanding “if there is rape, there must be evidence of struggle.” In a culture where the tendency is to hold the victim responsible for triggering the rape situation, this is dangerous. In anchoring rape in “consent”, the law recognizes the extenuating circumstances where a victim may not be able to physically resist or even say ‘no’. In Neruda’s account, the circumstances that prevent the woman from resisting or saying ‘no’ vocally are very clear. In hindsight, he too acknowledges her ‘no’: “She kept her eyes wide open all the while, completely unresponsive” (p. 100).

Beyond the issue of consent, his portrayal of the scene of rape also raises questions on how to represent violence on screen. Much has been written on the intrinsic violence of representation in attempts to represent violence. The risk is doubled when it comes to sexual violence as Laura Mulvey and others have pointed out as it turns spectators into voyeurs who wittingly or unwittingly participate in the violence enacted on screen. In Alborada, we all join Ratné Aiya at the “keyhole” or aperture to gaze at the scene unfolding within, whether we derive a vicarious pleasure from that or not. Handagama tries to draw the attention of the audience to the very real pain of the woman by having a tear course down her cheek as she stares directly at the camera and at us while averting her gaze from the perpetrator. By doing so, he restores the flesh-and-blood woman to the scene of the rape where Neruda had seen a statue. Unfortunately, the protracted violence of the rape scene is in danger of slipping from pathos to bathos. Sarath Chandrajeewa has already said that he found the scene where the predator and his prey circle round the massive four-poster bed comical. I agree. The scene was too reminiscent of “ottu sellang”, a children’s game of “catch me if you can”, for me!

Life after rape

Feminist critics such as Sharon Marcus and Rajeswari Sunder Rajan have emphasized the importance of rewriting the normative rape script which sees the woman as victim and her defilement as marking her for life. In Sri Lanka, women are enjoined to protect their character (a euphemism for sexual purity) as if it were their life, its loss a fate worse than death. Marcus and Sunder Rajan, therefore, argue that it is essential to speak of rape survivors, not rape victims, who thereby refuse the powerlessness assigned to them in a “gendered grammar of violence”(Marcus).

In Neruda’s memoirs, at the end of the account, attention is redirected to Neruda himself albeit on a note of self-recrimination: “She was right to despise me” (p. 100). The woman’s subsequent fate is of little concern to him. In the film, the lines translate into an image of Neruda trading places with the latrine cleaner, first taking up the brush and cleaning the latrine and then walking towards the sea carrying the latrine bucket on his head in a show of abject humility. As for the woman, the camera follows her out of the bedroom and into the sea where she tries frenziedly to rid herself of the defiling touch, her facial expressions indicating her disgust. She is then seen swimming deeper into the ocean, with the ocean waters gradually submerging her completely. Only the red cloth survives to create patterns in the water as it did at the start of the film. Clearly, there is no life after rape.

The film, however, adds another scene in an attempt to locate the phenomenon of rape in the present. In this scene the woman resurfaces from the sea framed against a skyline featuring a jet-ski. How to read it? Is it to remind the audience that, some one hundred years later, nothing much has changed? Or is to hold out hope that in the age of #MeToo, something is about to change?

But, according to Sarath Chandrajeewa (in “Beyond the Fiction of Alborada“)who claims to have traced the identity of the woman raped by Neruda, the “real” woman did not drown herself. She returned to her community but was married off by her family to an older man because she had “lost her virginity” and, when her husband died shortly after, the now pregnant woman jumped into the funeral pyre of her husband and committed suicide, which some in the community described as “Sathi Pooja”. Chandrajeewa even speculates that the husband’s death from alcohol poisoning was “either because he was delighted with his beautiful young bride or perhaps due to grief” (!). This information that Chandrajeewa says he gathered as part of his research among the Sakkili community who lived in Wellawatte and Bambalapitiya in the 1970s raises many questions for me. Did the community that the woman belonged to (the lowly scavenger caste) uphold norms of feminine sexual purity that have their basis in the genteel classes? Did they practice “Sathi Pooja” of which there are no documented cases in Ceylon and which, even in India is very much tied to region, class and caste as scholars like Lata Mani and Gayatri Spivak have pointed out? Pregnant women in any case do not commit Sathi Pooja. They wait until they give birth. How much does Chandrajeewa “know” of their ways?

This is not the only attempt at endowing the woman with an afterlife. Another account of the nameless woman’s subsequent fate has been doing the rounds of late due to an article by Kumar Gunawardena in The Island in 2020 where he, drawing on a story titled “Brumpy’s Daughter” in Tissa Devendra’s On Horseshoe Street, claims that the raped woman’s story had a happy ending. According to Gunawardena, Neruda “did the right thing” by the woman, who now has a name, Thangamma, by marrying her off to his retainer Brumpy. And when a daughter (Neruda’s) was born in due course, she was named Imelda after Neruda’s mother at his behest and supported financially by Neruda through George Keyt. Devendra meets Imelda Ratnayake (last name from the foster father Brumpy) much later when he is heading a Kachcheri where she too works and attracts his attention because of her striking appearance. She ends up marrying a Chilean, a Neruda devotee, who had worked for a while in Ceylon. After her marriage, Imelda settles in Chile with her husband and meets Devendra again at a conference in Mexico. It was a feel-good story. But the feeling was short-lived. When Michael Roberts reprinted Kumar Gunawardena’s account in his blog Thuppahi, someone by the name of Manel Fonseka intervened to spoil it by declaring “If I’m not mistaken, Devendra’s whole story was exactly that! A STORY! No basis in truth”. If Manel Fonseka is right, Gunawardena, a medical doctor by training, had failed to recognize the difference between fact and fiction!

In all this, there is no room for the subjectivity of the woman who was raped. She does not speak. For Neruda, the reason is the language barrier though he turns that into something more by comparing her to a “shy jungle animal” belonging in “another kind of existence, in another world” (p. 100). Handagama restores some humanity to her by adding that artistically placed single tear but that’s where he stops. She never speaks. The gaze in the film is predominantly Neruda’s, the camera angles adopting Neruda’s perspective on the receding figure of the latrine cleaner reminiscent of a classical South Indian sculpture although, unfortunately, her walk could well be that of a model on the runway. Similarly, her face takes on a bronze sheen when Neruda intercepts her to remind us that, in his mind, she resembles a statue. Given the race, caste, class and gender of the latrine cleaner, it is unlikely we will ever know what happened to her. Chandrajeewa, who claims he found the “real” woman, assigns her an exceptional fate as a “mad” woman (suffering from “Idiopathic Psychological Disorder”) who commits Sathi Pooja. Even Tissa Devendra’s story ultimately fails to imagine for her a life that is not defined by the rape. I like to think that there was life after rape for her, that she, though no doubt traumatized, survived the rape without having to play the prescribed role in the normative script for the rape victim–forced marriage and unwanted pregnancy–although, gender norms at the time being such, she could not cry out loud #HeToo!

(Carmen Wickramagamage is Professor in English at the University of Peradeniya)

Midweek Review

At the edge of a world war

In September 1939, as Europe descended once more into catastrophe, E. H. Carr published The Twenty Years’ Crisis. Twenty years had separated the two great wars—twenty years to reflect, to reconstruct, to restrain. Yet reflection proved fragile. Carr wrote with unsentimental clarity: once the enemy is crushed, the “thereafter” rarely arrives. The illusion that power can come first and morality will follow is as dangerous as the belief that morality alone can command power. Between those illusions, nations lose themselves.

His warning hovers over the present war in Iran.

The “thereafter” has long haunted American interventions—after Afghanistan, after Iraq, after Libya. The enemy can be dismantled with precision; the aftermath resists precision. Iran is not a small theater. It is a civilization-state with a geography three times larger than Iraq. At its southern edge lies the Strait of Hormuz, narrow in width yet immense in consequence. Geography does not argue; it compels.

Long before Carr, in the quiet anxiety of the eighteenth century, James Madison, principal architect of the Constitution, warned that war was the “true nurse of executive aggrandizement.” War concentrates authority in the name of urgency. Madison insisted that the power to declare war must rest with Congress, not the president—so that deliberation might restrain impulse. Republics persuade themselves that emergency powers are temporary. History rarely agrees.

Then, at 2:30 a.m., the abstraction becomes decision.

Donald Trump declares war on Iran. The announcement crosses continents before markets open in Asia. Within twenty-four hours, Ali Khamenei, who ruled for thirty-seven years, is killed. The President calls him one of history’s most evil figures and presents his death as an opening for the Iranian people.

In exile, Reza Pahlavi hails the moment as liberation. In less than forty-eight hours, the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps collapses under overwhelming air power. A regime that endured decades falls swiftly. Military efficiency appears absolute. Yet efficiency does not resolve legitimacy.

The joint strike with Israel is framed as necessary and pre-emptive. Retaliation follows across the Gulf. The architecture of energy trade becomes fragile. Shipping routes are recalculated. Markets respond before diplomacy finds its language.

It is measured in the price of petrol in Colombo. In the bus fare in Karachi. In the rising cost of cooking gas in Dhaka. It is heard in the anxious voice of a migrant worker in Doha calling home to Kandy, asking whether contracts will be renewed, whether flights will continue, whether wages will be delayed. It is calculated in foreign reserves already strained, in currencies that tremble at rumor, in budgets forced to choose between subsidy and solvency.

Zaara was the breadwinner of her house in Sri Lanka. Her husband had been unemployed for years. At last, he secured an opportunity to travel to Israel as a foreign worker—like many Sri Lankans who depend on employment in the Middle East. It was to be their turning point: a small house repaired, debts reduced, dignity restored.

Now she lowers her eyes when she speaks. For Zaara, geopolitics is not theory. It is fear measured in distance—between a construction site abroad and a village waiting at home.

The war in Iran has shattered calculations that once felt practical. Nations like Sri Lanka now require strategic foresight to navigate unfolding realities. Reactive responses—whether to natural disasters or external shocks like this conflict—can cripple economies far faster than gradual pressures. Disruptions to energy imports, migrant remittances, and foreign reserves show how distant wars ripple into daily lives.

War among great powers is debated in think tanks. Its consequences are lived in markets—and in quiet kitchens where uncertainty sits heavier than hunger.

The conflict does not unfold in isolation. It enters the strategic calculus of China and Russia, both attentive to precedent. Power projected beyond the Western hemisphere reshapes perceptions in the Eastern theater. Iran’s transformation intersects directly with broader alignments. In 2021, Beijing and Tehran signed a twenty-five-year strategic agreement. By 2025, China was purchasing the majority of Iran’s exported oil at discounted rates. Energy underwrote strategy. That continuity has been disrupted. Yet strategic relationships do not vanish; they adjust.

In Winds of Change, my new book, I reproduce Nicholas Spykman’s 1944 two-theater confrontation map—Europe and the Pacific during the Second World War. Spykman distinguished maritime power from amphibian projection. Control of the Rimland determined balance. Then, the United States fought across two vast theaters. Today, Europe remains unsettled through Ukraine, the Pacific simmers over Taiwan and the South China Sea, Latin America remains sensitive, and the Middle East has been abruptly transformed. The architecture of multi-theater tension reappears.

At this juncture, the reflections of Marwan Bishara acquire weight. America’s ultimate power, he argues, resides in deterrence, not in the habitual use of force. Power, especially when shared, stabilizes. Force, when used with disregard for international law, breeds instability and humiliation. Arrogance creates enemies and narrows judgment. It is no surprise that many Americans themselves believe the United States should not act alone.

America’s strength does not rest solely in its military reach. Its economy constitutes roughly one-third of global output and generates close to 40 percent of the world’s research and development. Structural power—economic, technological, institutional—has historically underwritten deterrence. When force becomes the primary instrument, influence risks becoming coercion.

The United States now confronts simultaneous pressures across continents. The Second World War demonstrated the capacity to sustain multi-theater engagement; the post-9/11 wars revealed the exhaustion that follows prolonged intervention. Iran, larger and geopolitically deeper, presents a scale that cannot be resolved by air power alone.

Carr’s “thereafter” waits patiently. Military victory may be swift; political reconstruction is slow. Bishara reminds us that deterrence sustains stability, while force risks unraveling it.

At the edge of a potential world war, the decisive question is not who strikes first, but who restrains longest.

History watches. And in places far from the battlefield, mothers wait for phone calls that may not come.

Asanga Abeyagoonasekera is a Senior Research Fellow at the Millennium Project, Washington, D.C., and the author of Winds of Change: Geopolitics at the Crossroads of South and Southeast Asia, published by World Scientific

Midweek Review

Live Coals Burst Aflame

Live coals of decades-long hate,

Are bursting into all-consuming flames,

In lands where ‘Black Gold’ is abundant,

And it’s a matter to be thought about,

If humans anywhere would be safe now,

Unless these enmities dying hard,

With roots in imperialist exploits,

And identity-based, tribal violence,

Are set aside and laid finally to rest,

By an enthronement of the principle,

Of the Equal Dignity of Humans.

By Lynn Ockersz

Midweek Review

Saga of the arrest of retired intelligence chief

Retired Maj. Gen. Suresh Sallay’s recent arrest attracted internatiattention. His long-expected arrest took place ahead of the seventh anniversary of the bombings. Multiple blasts claimed the lives of nearly 280 people, including 45 foreigners. State-owned international news television network, based in Paris, France 24, declared that arrest was made on the basis of information provided by a whistleblower. The French channel was referring to Hanzeer Azad Moulana, who earlier sought political asylum in the West and one-time close associate of State Minister Sivanesathurai Chandrakanthan aka Pilleyan. May be the fiction he wove against Pilleyan and others may have been to strengthen his asylum claim there. Moulana is on record as having told the British Channel 4 that Sallay allowed the attack to proceed with the intention of influencing the 2019 presidential election. The French news agency quoted an investigating officer as having said: “He was arrested for conspiracy and aiding and abetting the Easter Sunday attacks. He has been in touch with people involved in the attacks, even recently.”

****

Suresh Sallay of the Directorate of Military Intelligence (DMI) received the wrath of Yahapalana Prime Minister Ranil Wickremesinghe, in 2016, over the reportage of what the media called the Chavakachcheri explosives detection made on March 30, 2016. Premier Wickremesinghe found fault with Sallay for the coverage, particularly in The Island. Police arrested ex-LTTE child combatant Edward Julian, alias Ramesh, after the detection of one suicide jacket, four claymore mines, three parcels containing about 12 kilos of explosives, to battery packs and several rounds of 9mm ammunition, from his house, situated at Vallakulam Pillaiyar Kovil Street. Chavakachcheri police made the detection, thanks to information provided by the second wife of Ramesh. Investigations revealed that the deadly cache had been brought by Ramesh from Mannar (Detection of LTTE suicide jacket, mines jolts government: Fleeing Tiger apprehended at checkpoint, The Island, March 31, 2016).

The then Jaffna Security Forces Commander, Maj. Gen. Mahesh Senanayake, told the writer that a thorough inquiry was required to ascertain the apprehended LTTE cadre’s intention. The Chavakachcheri detection received the DMI’s attention. The country’s premier intelligence organisation meticulously dealt with the issue against the backdrop of an alleged aborted bid to revive the LTTE in April 2014. Of those who had been involved in the fresh terror project, three were killed in the Nedunkerny jungles. There hadn’t been any other incidents since the Nedunkerny skirmish, until the Chavakachcheri detection.

Piqued by the media coverage of the Chavakachcheri detection, the Sirisena-Wickremesinghe administration tried to silence the genuine Opposition. As the SLFP had, contrary to the expectations of those who voted for the party at the August 2015 parliamentary elections, formed a treacherous coalition with the UNP, the Joint Opposition (JO) spearheaded the parliamentary opposition.

The Criminal Investigation Department (CID) questioned former External Affairs Minister and top JO spokesman, Prof. G.L. Peiris, over a statement made by him regarding the Chavakachcheri detection. The former law professor questioned the legality of the CID’s move against the backdrop of police declining to furnish him a certified copy of the then acting IGP S.M. Wickremesinghe’s directive that he be summoned to record a statement as regards the Chavakachcheri lethal detection.

One-time LTTE propagandist Velayutham Dayanidhi, a.k.a. Daya Master, raised with President Maithripala Sirisena the spate of arrests made by law enforcement authorities, in the wake of the Chavakachcheri detection. Daya Master took advantage of a meeting called by Sirisena, on 28 April, 2016, at the President’s House, with the proprietors of media organisations and journalists, to raise the issue. The writer having been among the journalists present on that occasion, inquired from the ex-LETTer whom he represented there. Daya Master had been there on behalf of DAN TV, Tamil language satellite TV, based in Jaffna. Among those who had been detained was Subramaniam Sivakaran, at that time Youth Wing leader of the Illankai Thamil Arasu Kadchi (ITAK), the main constituent of the now defunct Tamil National Alliance. In addition to Sivakaran, the police apprehended several hardcore ex-LTTE cadres (LTTE revival bid confirmed: TNA youth leader arrested, The Island April 20, 2016).

Ranil hits out at media

Subsequent inquiries revealed the role played by Sivakaran in some of those wanted in connection with the Chavakachcheri detection taking refuge in India. When the writer sought an explanation from the then TNA lawmaker, M.A. Sumanthiran, regarding Sivakaran’s arrest, the lawyer disowned the Youth Wing leader. Sumanthiran emphasised that the party suspended Sivakumaran and Northern Provincial Council member Ananthi Sasitharan for publicly condemning the TNA’s decision to endorse Maithripala Sirisena’s candidature at the 2015 presidential election (Chava explosives: Key suspects flee to India, The Island, May 2, 2016).

Premier Wickremesinghe went ballistic on May 30, 2016. Addressing the 20th anniversary event of the Sri Lanka Muslim Media Forum, at the Sports Ministry auditorium, the UNP leader castigated the DMI. Alleging that the DMI had been pursuing an agenda meant to undermine the Yahapalana administration, Wickremesinghe, in order to make his bogus claim look genuine, repeatedly named the writer as part of that plot. Only Wickremesinghe knows the identity of the idiot who influenced him to make such unsubstantiated allegations. The top UNPer went on to allege that The Island, and its sister paper Divaina, were working overtime to bring back Dutugemunu, a reference to war-winning President Mahinda Rajapaksa. A few days later, sleuths from the Colombo Crime Detection Bureau (CCD) visited The Island editorial to question the writer where lengthy statements were recorded. The police were acting on the instructions of the then Premier, who earlier publicly threatened to send police to question the writer.

In response to police queries about Sallay passing information to the media regarding the Chavakachcheri detection and subsequent related articles, the writer pointed out that the reportage was based on response of the then ASP Ruwan Gunasekera, AAL and Sumanthiran, as had been reported.

Wickremesinghe alleged, at the Muslim media event, that a section of the media manipulated coverage of certain incidents, ahead of the May Day celebrations.

In early May 2016 Wickremesinghe disclosed that he received assurances from the police, and the DMI, that as the LTTE had been wiped out the group couldn’t stage a comeback. The declaration was made at the Lakshman Kadirgamar Institute for International Relations and Strategic Studies (LKIIRIS) on 3 May 2016. Wickremesinghe said that he sought clarifications from the police and the DMI in the wake of the reportage of the Chavakachcheri detection and related developments (PM: LTTE threat no longer exists, The Island, May 5, 2016).

The LTTE couldn’t stage a comeback as a result of measures taken by the then government. It would be a grave mistake, on our part, to believe that the eradication of the LTTE’s conventional military capacity automatically influenced them to give up arms. The successful rehabilitation project, that had been undertaken by the Rajapaksa government and continued by successive governments, ensured that those who once took up arms weren’t interested in returning to the same deadly path.

In spite of the TNA and others shedding crocodile tears for the defeated Tigers, while making a desperate effort to mobilise public opinion against the government, the public never wanted the violence to return. Some interested parties propagated the lie that regardless of the crushing defeat suffered in the hands of the military, the LTTE could resume guerilla-type operations, paving the way for a new conflict. But by the end of 2014, and in the run-up to the presidential election in January following year, the situation seemed under control, especially with Western countries not wanting to upset things here with a pliant administration in the immediate horizon. Soon after the presidential election, the government targeted the armed forces. Remember Sumanthiran’s declaration that the ITAK Youth Wing leader Sivakaran had been opposed to the TNA backing Sirisena at the presidential poll.

The US-led accountability resolution had been co-sponsored by the Sirisena-Wickremesinghe duo to appease the TNA and Tamil Diaspora. The Oct. 01, 2016, resolution delivered a knockout blow to the war-winning armed forces. The UNP pursued an agenda severely inimical to national interests. It would be pertinent to mention that those who now represent the main Opposition, Samagi Jana Balawegaya (SJB), were part of the treacherous UNP.

Suresh moved to Malaysia

The Yahapalana leadership resented Sallay’s work. They wanted him out of the country at a time a new threat was emerging. The government attacked the then Justice Minister Dr. Wijeyadasa Rajapakshe, PC, who warned of the emerging threat from foreign-manipulated local Islamic fanatics on 11 Nov. 2016, in Parliament. Rajapakshe didn’t mince his words when he underscored the threat posed by some Sri Lanka Muslim families taking refuge in Syria where ISIS was running the show. The then government, of which he was part o,f ridiculed their own Justice Minister. Both Sirisena and Wickremesinghe feared action against extremism may cause erosion of Muslim support. By then Sallay, who had been investigating the deadly plot, was out of the country. The Yahapalana government believed that the best way to deal with Sallay was to grant him a diplomatic posting. Sally ended up in Malaysia, a country where the DMI played a significant role in the repatriation of Kumaran Pathmanathan, alias KP, after his arrest there.

The Yahapalana leadership resented Sallay’s work. They wanted him out of the country at a time a new threat was emerging. The government attacked the then Justice Minister Dr. Wijeyadasa Rajapakshe, PC, who warned of the emerging threat from foreign-manipulated local Islamic fanatics on 11 Nov. 2016, in Parliament. Rajapakshe didn’t mince his words when he underscored the threat posed by some Sri Lanka Muslim families taking refuge in Syria where ISIS was running the show. The then government, of which he was part o,f ridiculed their own Justice Minister. Both Sirisena and Wickremesinghe feared action against extremism may cause erosion of Muslim support. By then Sallay, who had been investigating the deadly plot, was out of the country. The Yahapalana government believed that the best way to deal with Sallay was to grant him a diplomatic posting. Sally ended up in Malaysia, a country where the DMI played a significant role in the repatriation of Kumaran Pathmanathan, alias KP, after his arrest there.

Having served the military for over three cadres, Sallay retired in 2024 in the rank of Major General. Against the backdrop of his recent arrest, in connection with the ongoing investigation into the 2019 Easter Sunday carnage, The Island felt the need to examine the circumstances Sallay ended up in Malaysia at the time. Now, remanded in terms of the Prevention of terrorism Act (PTA), he is being accused of directing the Easter Sunday operation from Malaysia.

Pivithuru Hela Urumaya leader and former Minister Udaya Gammanpila has alleged that Sallay was apprehended in a bid to divert attention away from the deepening coal scam. Having campaigned on an anti-corruption platformm in the run up to the previous presidential election, in September 2024, the Parliament election, in November of the same year, and local government polls last year, the incumbent dispensation is struggling to cope up with massive corruption issues, particularly the coal scam, which has not only implicated the Energy Minister but the entire Cabinet of Ministers as well.

The crux of the matter is whether Sallay actually met would-be suicide bombers, in February 2018, in an estate, in the Puttalam district, as alleged by the UK’s Channel 4 television, like the BBC is, quite famous for doing hatchet jobs for the West. This is the primary issue at hand. Did Sallay clandestinely leave Malaysia to meet suicide bombers in the presence of Hanzeer Azad Moulana, one-time close associate of State Minister Sivanesathurai Chandrakanthan, aka Pilleyan, former LTTE member?

The British channel raised this issue with Sallay, in 2023, at the time he served as Director, State Intelligence (SIS). Sallay is on record as having told Channel 4 Television that he was not in Sri Lanka the whole of 2018 as he was in Malaysia serving in the Sri Lankan Embassy there as Minister Counsellor.

Therefore, the accusation that he met several members of the National Thowheeth Jamaath (NTJ), including Mohamed Hashim Mohamed Zahran, in Karadipuval, Puttalam, in Feb. 2018, was baseless, he has said.

The intelligence officer has asked the British television station to verify his claim with the Malaysian authorities.

Responding to another query, Sallay had told Channel 4 that on April 21, 2019, the day of the Easter Sunday blasts, he was in India, where he was accommodated at the National Defence College (NDC). That could be verified with the Indian authorities, Sallay has said, strongly denying Channel 4’s claim that he contacted one of Pilleyan’s cadres, over, the phone and directed him to pick a person outside Hotel Taj Samudra.

According to Sallay, during his entire assignment in Malaysia, from Dec. 2016 to Dec. 2018, he had been to Colombo only once, for one week, in Dec. 2017, to assist in an official inquiry.

Having returned to Colombo, Sallay had left for NDC, in late Dec. 2018, and returned only after the conclusion of the course, in November 2019.

Sallay has said so in response to questions posed by Ben de Pear, founder, Basement Films, tasked with producing a film for Channel 4 on the Easter Sunday bombings.

The producer has offered Sallay an opportunity to address the issues in terms of Broadcasting Code while inquiring into fresh evidence regarding the officer’s alleged involvement in the Easter Sunday conspiracy.

The producer sought Sallay’s response, in August 2023, in the wake of political upheaval following the ouster of Gotabaya Rajapaksa, elected at the November 2019 presidential election.

At the time, the Yahapalana government granted a diplomatic appointment to Sallay, he had been head of the Directorate of Military Intelligence (DMI). After the 2019 presidential election, President Gotabaya Rajapaksa named him the Head of SIS.

The Basement Films has posed several questions to Sallay on the basis of accusations made by Hanzeer Azad Moulana.

In response to the film producer’s query regarding Sallay’s alleged secret meeting with six NTJ cadres who blasted themselves a year later, Sallay has questioned the very basis of the so called new evidence as he was not even in the country during the period the clandestine meeting is alleged to have taken place.

Contradictory stands

Following Sajith Premadasa’s anticipated defeat at the 2019 presidential election, Harin Fernando accused the Catholic Church of facilitating Gotabaya Rajapaksa’s victory. Fernando, who is also on record as having disclosed that his father knew of the impending Easter Sunday attacks, pointed finger at the Archbishop of Colombo, Rt. Rev Malcolm Cardinal Ranjith, for ensuring Gotabaya Rajapaksa’s victory.

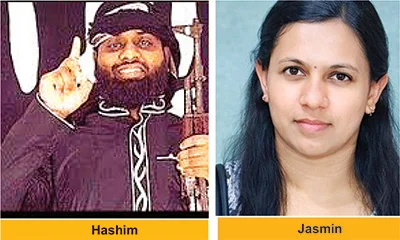

Former President Maithripala Sirisena, as well as JVP frontliner Dr. Nalinda Jayathissa, accused India of masterminding the Easter Sunday bombings. Then there were claims of Sara Jasmin, wife of Katuwapitiya suicide bomber Mohammed Hastun, being an Indian agent who was secretly removed after the Army assaulted extremists’ hideout at Sainthamaruthu in the East. What really had happened to Sara Jasmin who, some believe, is key to the Easter Sunday puzzle.

Then there was huge controversy over the arrest of Attorney-at-Law Hejaaz Hizbullah over his alleged links with the Easter Sunday bombers. Hizbullah, who had been arrested in April 2020, served as lawyer to the extremely wealthy spice trader Mohamed Yusuf Ibrahim’s family that had been deeply involved in the Easter Sunday plot. Mohamed Yusuf Ibrahim had been on the JVP’s National List at the 2015 parliamentary elections. The lawyer received bail after two years. Two of the spice trader’s sons launched suicide attacks, whereas his daughter-in-law triggered a suicide blast when police raided their Dematagoda mansion, several hours after the Easter Sunday blasts.

Investigations also revealed that the suicide vests had been assembled at a factory owned by the family and the project was funded by them. It would be pertinent to mention that President Gotabaya Rajapaksa’s government never really bothered to conduct a comprehensive investigation to identify the Easter Sunday terror project. Perhaps, their biggest failure had been to act on the Presidential Commission of Inquiry (PCoI) recommendations. Instead, President Rajapaksa appointed a six-member committee, headed by his elder brother, Chamal Rajapaksa, to examine the recommendations, probably in a foolish attempt to improve estranged relations with the influential Muslim community. That move caused irreparable damage and influenced the Church to initiate a campaign against the government. The Catholic Church played quite a significant role in the India- and US-backed 2022 Aragalaya that forced President Rajapaksa to flee the country.

Interested parties exploited the deterioration of the national economy, leading to unprecedented declaration of the bankruptcy of the country in April 2022, to mobilie public anger that was used to achieve political change.

-

News4 days ago

News4 days agoUniversity of Wolverhampton confirms Ranil was officially invited

-

News5 days ago

News5 days agoLegal experts decry move to demolish STC dining hall

-

News4 days ago

News4 days agoFemale lawyer given 12 years RI for preparing forged deeds for Borella land

-

News3 days ago

News3 days agoPeradeniya Uni issues alert over leopards in its premises

-

Business5 days ago

Business5 days agoCabinet nod for the removal of Cess tax imposed on imported good

-

News4 days ago

News4 days agoLibrary crisis hits Pera university

-

News3 days ago

News3 days agoWife raises alarm over Sallay’s detention under PTA

-

Business6 days ago

Business6 days agoWar in Middle East sends shockwaves through Sri Lanka’s export sector