Midweek Review

Against flawed assumptions and false analogies

By Uditha Devapriya

“It is not enough to have a philosophy, you have to have the right philosophy.”

— Joan Robinson to the then Central Bank Deputy Governor, quoted by S. B. D. de Silva

Academics and students tend to subscribe to certain dominant ideological paradigms, the assumptions which underlie them, and the conclusions those assumptions lead them to. Given that universities, particularly local universities, have turned into knowledge factories preferring unconditional acceptance to critical thinking, false paradigms and analogies get perpetuated easily. They get embedded in school curricula, public forums, and of course the public sphere: as much in the lecture hall as in parliament.

Most of these paradigms delve into what the best way forward for the country should be, economically and politically, or what it should not be. For instance, the Vehicle Importers’ Association of Sri Lanka in a recent letter to the President cautions him against the belief that local manufacture and assembly is the answer to Sri Lanka’s mounting debt and foreign exchange crisis. The reason, whoever wrote that letter avers, is that the process “does not add any value to the country’s economy and is merely designed for tax evasion and higher profit margins.” Further, it warns that “setting up a vehicle manufacturing plant is a lengthy process with extensive planning and research and development.”

This is more or less a rehash of the line that advocates of free markets and free trade take up. The 2021 Budget, with its emphasis on import restrictions and concessions to local businesses, including manufacturers, compelled the same response from these advocates in Parliament. According to them, it favours import substitution over export orientation, cuts the country from the benefits of free trade, and isolates it from the rest of the world. The one leads to the other: if we manufacture locally, we lose out on trade. If we lose out on trade, we lose out on everything. Ergo, we mustn’t think or go local.

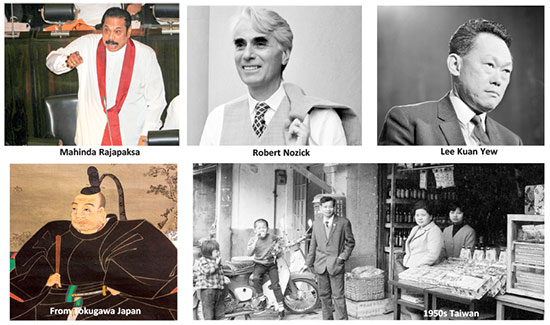

Intellectuals and commentators, especially in (but not necessarily limited to) the English language media, tend to extol the virtues of free markets and the evils of state-led growth. They seem to think that Sri Lanka for the most has been caving into the latter paradigm: the state has widened at the expense of the private sector. The solution, according to pundits and analysts, is to let the market decide, and to limit the government to the role of what Robert Nozick called a “Night-watchman”, formulating the rules of the game (the economy) without playing it (intervening in the workings of the economy). These pundits and analysts then point at societies that supposedly prospered under a night-watchman state: the Tiger economies of East Asia, the US, and Western Europe.

Now quite a lot of people believe this. They accept it as patently obvious: a tautology which, if denied, would lead to a contradiction. British philosophers of the 18th century made a distinction between two kinds of statements: “All thieves are criminals” and “Richard is a thief.” The first is self-evident: to deny it would be to defy logic. In other words it exists a priori: you know it’s true even if you don’t try to prove it. The second is not self-evident: you need empirical evidence to test its validity. Such statements of opinion require proof before one can know whether they are true or false. In the social sciences as in the hard sciences, then, critical analysis and logical reasoning are absolutely indispensable.

Unfortunately, much of the hype surrounding advocacy of free market principles and small government is built on a self-evident premise: people believe economic liberalisation will lead to growth, so they think it should be implemented in the country. Import tariffs must be reduced or preferably eliminated, export-orientation must replace import-substitution, let’s not think of local industrialisation or machine-manufacture yet because we’re an island, and let’s reduce the role of the state because, after all, in the US, Britain, and East Asia, it played a minimal role. Ignored in the emphasis on the success of the latter countries is the specificity of their historical experience.

Countries are not all endowed with the same levels or the same kinds of resources. Nor do they magically transit to free markets and small governments. To say economic liberalisation worked there and that owing to it these principles must be applied here is to assume that all it takes for a country to prosper is the implementation of policies to which those countries which are supposedly implementing them now resorted only after they had passed through certain stages. This assumption, quoting the late S. B. D. de Silva, is “a veritable non-sequitur of bourgeois scholarship.” Taking the earlier argument into consideration, such assumptions are paraded as tautologies when in fact they are not. What is missing from the argument, in other words, is the same thing its proponents accuse the other side, i.e. the Big Government protectionist lobby, of lacking: reasoned, analytical judgement.

The US got to where it is largely through its leap to industrialisation in the latter part of the 19th century. Much of the industrialisation which transpired at that time was financed, not by private initiative, but by the government: vast tracts of land running into millions of acres were handed over to railway companies. In Britain, the state played an important role in promoting local industry, smothering the up-and-coming textile mills of India. Discussions about the success of private sector led growth in these countries leave out or ignore the role played by colonial conquest, which happened to be financed by the government. “Is there any greater example of a rampant state than the English state in the world?” asked a friend at an Advocata Night-Watchman seminar years ago. “When you’re talking laissez-faire, they were basically robbing the seas around the world, installing slavery.” True.

The US got to where it is largely through its leap to industrialisation in the latter part of the 19th century. Much of the industrialisation which transpired at that time was financed, not by private initiative, but by the government: vast tracts of land running into millions of acres were handed over to railway companies. In Britain, the state played an important role in promoting local industry, smothering the up-and-coming textile mills of India. Discussions about the success of private sector led growth in these countries leave out or ignore the role played by colonial conquest, which happened to be financed by the government. “Is there any greater example of a rampant state than the English state in the world?” asked a friend at an Advocata Night-Watchman seminar years ago. “When you’re talking laissez-faire, they were basically robbing the seas around the world, installing slavery.” True.

In East Asia three distinct case studies can be identified: Japan, Taiwan and South Korea, and Singapore. The foundation for Japan’s economy was laid down long before the war by the Tokugawa shogunate; it broke the stranglehold of petty traders, privileging industrial capital over merchant finance. Taiwan emerged from the war cut off from mainland China after the Communist takeover of 1949, yet American experts and economists who formulated that country’s transition to economic liberalisation didn’t embark on free market reforms right away: at first they oversaw rent reduction in 1949, the sale of public lands in 1951, and the commencement of a land-to-the-tiller program in 1953. Land reform limited ownership of paddy land to around 4.5 hectares, much lower than the 10-25 hectare limit imposed by the Sirimavo Bandaranaike government in 1972. South Korea underwent roughly the same set of reforms before it attained first world status.

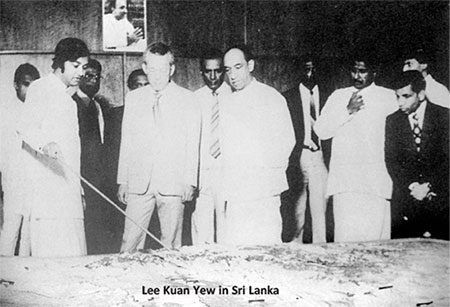

Singapore is a different case, not least because unlike other East Asian countries it lacked a rural hinterland in which a transition from agriculture to industry could take place. Yet there too the role of government intervention cannot be denied, economically and also politically. Milton Friedman once referred to Lee Kuan Yew as a “benevolent dictator”, the very same epithet Maithripala Sirisena used on Mahinda Rajapaksa in 2014 after walking out from the then administration. In a 1993 essay, William Gibson described the country as “Disneyland with the Death Penalty”, bringing to mind Jagath Manuwarna’s remark about Sri Lanka at a press conference in late 2014: “kalakanni Disneylanthaya.” Unlike Manuwarna’s statement though, Gibson’s essay was banned by the Singaporean government.

Liberals and classical liberals, and even left-liberals, tend to look up to Singapore and Yew’s reforms without realising that, as Regi Siriwardena observed, their achievements rested on the denial of democratic and human rights. Hence when one columnist, drawing wildly false analogies, argues that Singapore lacked a president, yet accomplished much (implying that Sri Lanka doesn’t need an Executive Presidency to get things done), he fails to acknowledge or chooses to ignore not only that Singapore had just one political party during its transition from third world to first, but also that it curtailed dissent in a way that makes any hounding of dissent in Sri Lanka today look haphazard in comparison; when asked why he refused to tolerate political cartoons, for instance, Yew bluntly told Fergus Bordewich that in Confucian society politicians ought to be seen as deserving of respect. To my mind no parliamentarian in Sri Lanka has ever said the same thing using Buddhism as justification. I suppose that has to do with how free the media here is compared to the media there: the latest World Press Freedom Index, for instance, ranks Sri Lanka at 127, and Singapore at 158.

The absence of a rural hinterland made it all the easier for Singapore’s government to enact capitalist reforms, since it could dispense with the need to abolish the kind of pre-capitalist social relations that existed in Taiwan and South Korea. Despite this, however, government intervention swept across the country; in the words of one economist, Singapore responded to international economic forces “through manipulating the domestic economy.”

Wage adjustments vis-à-vis a National Wages Council, a high savings and investment culture promoted via state enforced and state directed abstinence, the shift towards manufacturing in the latter part of the 1960s, the growth of public enterprises (believed to have accounted for 14% to 16% of manufacturing output), and tight government control of trade unions all played a part in bolstering its prospects. As Hoff (1995) noted, the paradox of Singapore’s economic success was that while investments came from the private sector, savings relied on the public sector. It is true that the contribution by foreign investment was significant, yet had Singapore not had a rigidly regulated economy where, for instance, compensation costs for production workers were one-third that of the US equivalent by 1993, it would not have become the third world to first success story it is touted as today.

The specific conditions under which the East Asian economies transformed from developing to developed, from inward-looking to outward-looking, make their emulation in other parts of the world untenable if not unlikely. At the time the governments of these countries were imposing reforms, Western Europe was struggling to recover from wartime recession and MNCs had not become as active in peripheral countries as they would decades later. Their geopolitical alignment with the US in the Cold War guaranteed the success of the East Asian Tigers. Moreover, these were hardly what one could call classical liberal societies: political authoritarianism cohabited with economic liberalisation. Even that dichotomy comes off as false when we consider that government involvement figured heavily in these economies, something that advocates of free markets don’t seem to be aware of.

There was another significant factor: the absence of a merchant capitalist class in these countries. The Tokugawa reforms extended to Korea and Taiwan after Japan turned them into granaries for its domestic needs. The US experts hired to oversee reforms in Korea and Taiwan facilitated, rather than reversed, these processes. In Sri Lanka and much of the Third World, by contrast, experimentation with free market classical liberalism has resulted in not only political authoritarianism, but also the defenestration of an industrial sector, leading to lopsided growth financed by a Pettah merchant class: rather than manufacturing goods, they are imported and resold. The call for “going local”, then, contrary to what intellectuals, institutions, and Opposition MPs think, say, and write, has to do with more than a hysterical call for a garrison state. COVID-19 has sharpened the contradictions of the global economy. The World Bank and IMF paradigm of outward-oriented development is clearly not the way to go about, if we are to resolve these contradictions.

False analogies, assumptions, and tautologies thus will get us nowhere. It is certainly ironic that think-tanks and institutions that privilege reason over guesswork end up indulging in selective scholarship. Even more ironic are statements uttered by academics from countries which passed through several stages before making the transition from a planned order to a free market advising us to bypass those stages when implementing policy reforms here. It takes not only foresight and hindsight, but also courage, to swerve from and dispute these assumptions, dig deep into history, and understand what drives the wealth of nations and the poverty of others. Free markets alone will not do, as even the history of countries where they flourish today tell us. Something else can, and something else must.

Midweek Review

Dr. Jaishankar drags H’tota port to reverberating IRIS Dena affair

Indian Foreign Minister Dr. S. Jaishankar recognised Hambantota harbour as a Chinese military facility that underlined intimidating foreign military presence in the Indian Ocean. Jaishankar was responding to queries regarding India’s widely mentioned status as the region’s net security provider against the backdrop of a US submarine blowing up an Iranian frigate IRIS Dena, off Galle, within Sri Lanka’s Exclusive Economic Zone.

This happened at the Raisina Dialogue 2026 (March 5 to 7) in New Delhi. Raisina Dialogue was launched in 2016, three years after Narendra Modi became the Prime Minister.

The query obviously rattled the Indian Foreign Minister. Urging the moderator, Ms. Pakli Sharma Ipadhyay, to understand, what he called, the reality of the Indian Ocean, Dr. Jaishankar pointed out the joint US-British presence at Diego Garcia over the past five decades. Then he referred to the Chinese presence at Djibouti in East Africa, the first overseas Chinese military base, established in 2017, and Chinese takeover of Hambantota port, also during the same time. China secured the strategically located port on a 99-year lease for USD 1.2 bn, under controversial circumstances. China succeeded in spite of Indian efforts to halt Chinese projects here, including Colombo port city.

The submarine involved is widely believed to be Virginia-class USS Minnesota. The crew, included three Australian Navy personnel, according to international news agencies. However, others named the US Navy fast-attack submarine, involved in the incident, as USS Charlotte.

Diego Garcia is responsible for military operations in the Middle East, Africa and the Indo-Pacific. Dr. Jaishankar didn’t acknowledge that India, a key US ally and member of the Quad alliance, operated P8A maritime patrol and reconnaissance flights out of Diego Garcia last October. The US-India-Israel relationship is growing along with the US-Sri Lanka partnership.

The Indian Foreign Minister emphasised the deployment of the US Fifth Fleet in Bahrain, one of the countries that had been attacked by Iran, following the US-Israeli assassination of Iranian Supreme Leader, and key government functionaries, in a massive surprise attack, aiming at a regime change there. The Indian Minister briefly explained how they and Sri Lanka addressed the threat on three Indian navy vessels following the unprovoked US-Israeli attacks on Iran. Whatever the excuses, the undeniable truth is, as Sharma pointed out, that the US attack on the Iranian frigate took place in India’s backyard.

Sri Lankan Foreign Minister Vijitha Herath who faced Sharma before Dr. Jaishankar, struggled to explain the country’s position. Dr. Jaishankar made the audience laugh at Minister Herath’s expense who repeatedly said that Sri Lanka would deal with the situation in terms of the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) and international laws. Herath should have pointed out that Hambantota was not a military base and couldn’t be compared, under any circumstances, with the Chinese base in Djibouti.

Typical of the arrogant Western power dynamics, the US never cared for international laws and President Donald Trump quite clearly stated their position.

Israel is on record as having declared that the decision to launch attacks on Iran had been made months ago. Therefore, the sinking of the fully domestically built vessel that was launched in 2021 should be examined in the context of overall US-Israeli strategy meant to break the back of the incumbent Islamic revolutionary government and replace it with a pro-Western regime there as had been the case after the toppling of the democratically elected government there, led by Prime Minister Mossadegh, in August, 1953.

US Defence Secretary Pete Hegseth declared that IRIS Dena “thought it was safe in international waters’ but died a quiet death.” A US submarine torpedoed the vessel on the morning of March 4, off Galle, within Sri Lanka’s exclusive economic zone and that decision must have been made before the IRIS Dena joined International Fleet Review (IFR) and Exercise Milan 2026, at Visakhapatnam, from February 15 to 25.

The sinking of the Iranian vessel, a Moudge –class frigate attached to Iran’s southern fleet deployed in the Gulf of Oman and Strait of Hormuz, had been calculated to cause mayhem in the Indian Ocean. Obviously, and pathetically, Iran failed to comprehend the US-Israeli mindset after having already been fooled with devastating attacks, jointly launched by Washington and Tel Aviv against the country’s nuclear research facilities, while holding talks with it on the issue last June. Had they comprehended the situation they probably would have pulled out of the IFR and Milan 2026. Perhaps, Iran was lulled into a false sense of security because they felt the US wouldn’t hit ships invited by India. The US Navy did not participate though the US Air Force did.

The US action dramatically boosted Raisina Dialogue 2026, but at India’s expense. Prime Minister Modi’s two-day visit to Tel Aviv, just before the US-Israel launched the war to effect a regime change in Teheran, made the situation far worse. BJP seems to have decided on whose side India is on. But, the US action has, invariably, humiliated India. That cannot be denied. The Indian Navy posted a cheery message on X on February 17, the day before President Droupadi Murmu presided over IFR off the Visakhapatnam coast. “Welcome!” the Indian Navy wrote, greeting the Iranian warship IRIS Dena as it steamed into the port of Visakhapatnam to join an international naval gathering. Photographs showed Iranian sailors and a grey frigate gliding into the Indian harbour on a clear day. The hashtags spoke of “Bridges of Friendship” and “United Through Oceans.”

US alert

Dr. Jaishankar

Altogether, three Iranian vessels participated in IFR. In addition to the ill-fated IRIS Dena, the second frigate IRIS Lavan and auxiliary ships IRIS Bushehr comprised the group. Dr. Jaishankar disclosed at the Raisina Dialogue 2026 that Iran requested India to allow IRIS Lavan to enter Indian waters. India accommodated the vessel at Cochin Port (Kochi Port) on the Arabian Sea in Kerala.

At the time US torpedoed IRIS Dena, within Sri Lanka’s EEZ, IRIS Lavan was at Cochin port. Sri Lanka’s territorial waters extend 12 nautical miles (approximately 22 km) from the country’s coastline. The US hit the vessel 19 nautical miles off southern coastline.

Sri Lanka, too, participated in IFR and Milan 2026. SLN Sagara (formerly Varaha), a Vikram-class offshore patrol vessel of the Indian Coast Guard and SLN Nandimithra, A Fast Missile Vessel, acquired from Israel, participated and returned to Colombo on February 27, the day before IRIS Lavan sought protection in Indian waters.

Although many believed that Sri Lanka responded to the attack on IRIS Dena, following a distressed call from that ship, the truth is it was the Indo-Pacific Command (INDOPACOM) that alerted the Maritime Rescue Coordination centre (MRCC) after blowing it up with a single torpedo. The SLN’s Southern Command dispatched three Fast Attack Craft (FACs) while a tug from Sri Lanka Ports Authority (SLPA) joined later.

The INDOPACOM, while denying the Iranian claim that IRIS Dena had been unarmed at the time of the attack, emphasised: “US forces planned for and Sri Lanka provided life-saving support to survivors in accordance with the Law of Armed Conflict.” In the post shared on X (formerly Twitter) the US has, in no uncertain terms, said that they planned for the rescuing of survivors and the action was carried out by the Sri Lanka Navy.

IRIS Lavan and IRIS Bushehr are most likely to be held in Cochin and in Trincomalee ports, respectively, for some time with the crews accommodated on land. With the US-Israel combine vowing to go the whole hog there is no likelihood of either India or Sri Lanka allowing the ships to leave.

Much to the embarrassment of the Modi administration, former Indian Foreign Secretary Kanwal Sibal has said that IRIS Dena would not have been targeted if Iran was not invited to take part in IFR and Milan naval exercise.

“We were the hosts. As per protocol for this exercise, ships cannot carry any ammunition. It was defenseless. The Iranian naval personnel had paraded before our president,” he said in a post on X.

Sibal argued that the attack was premeditated, pointing out that the US Navy had been invited to the exercise but withdrew at the last minute, “presumably with this operation in mind.”

Sibal added that the US ignored India’s sensitivities, as the Iranian ship was present in the waters due to India’s invitation.

He stressed that India was neither politically nor militarily responsible for the US attack, but carried a moral and humanitarian responsibility.

“A word of condolence by the Indian Navy (after political clearance) at the loss of lives of those who were our invitees and saluted our president would be in order,” Sibal said.

Iran and even India appeared to have ignored the significance of USN pullout from IFR and Milan exercise at the eleventh hour. India and Sri Lanka caught up in US-Israeli strategy are facing embarrassing questions from the political opposition. Both Congress and Samagi Jana Balwegaya (SJB), as well as Sri Lanka Podujana Peramuna (SLPP), exploited the situation to undermine respective governments over an unexpected situation created by the US. Both India and Sri Lanka ended up playing an unprecedented role in the post-Milan 2026 developments that may have a lasting impact on their relations with Iran.

The regional power India and Sri Lanka also conveniently failed to condemn the February 28 assassination of Iranian Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, while that country was holding talks with the US, with Oman serving as the mediator.

Condemning the unilateral attack on Iran, as well as the retaliatory strikes by Iran, Leader of the Opposition in the Lok Sabha and Congress leader Rahul Gandhi on Tuesday (March 3, 2026) questioned India’s silence on the Middle East developments.

In a post on social media platform X, Gandhi said Prime Minister Narendra Modi must speak up. “Does he support the assassination of a Head of State as a way to define the world order? Silence now diminishes India’s standing in the world,” he said.

Under heavy Opposition fire, India condoled the Iranian leader’s assassination on March 5, almost a week after the killing. Foreign Secretary Vikram Misri met the Iran Ambassador in Delhi and signed the condolence book, though much belatedly.

SL-US relations

The Opposition questioned the NPP government’s handling of the IRIS Dena affair. They quite conveniently forgot that any other government wouldn’t have been able to do anything differently than bow to the will of the US. Under President Trump, Washington has been behaving recklessly, even towards its longtime friends, demanding that Canada become its 51st state and that Denmark handover Greenland pronto.

SJB and Opposition leader Sajith Premadasa cut a sorry figure demanding in Parliament whether Sri Lanka had the capacity to detect submarines or other underwater systems. Sri Lanka should be happy that the Southern Command could swiftly deploy three FACs and call in SLPA tug, thereby saving the lives of 32 Iranians and recovering 84 bodies of their unfortunate colleagues. Therefore, of the 180-member crew of IRIS Dena, 116 had been accounted for. The number of personnel categorised as missing but presumably dead is 64.

There is no doubt that Sri Lanka couldn’t have intervened if not for the US signal to go ahead with the humanitarian operation to pick up survivors. India, too, must have informed the US about the Iranian request for IRIS Lavan to re-enter Indian waters. Sri Lanka, too, couldn’t have brought the Iranian auxiliary vessel without US consent. President Trump is not interested in diplomatic niceties and the way he had dealt with European countries repeatedly proved his reckless approach. The irrefutable truth is that the US could have torpedoed the entire Iranian group even if they were in Sri Lankan or Indian Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ) that extends to 200 nautical miles from its coastline.

In spite of constantly repeating Sri Lanka’s neutrality, successive governments succumbed to US pressure. In March 2007, Mahinda Rajapaksa’s government entered into Acquisition and Cross- Servicing Agreement (ACSA) with the US, a high profile bilateral legal mechanism to ensure uninterrupted support/supplies. The Rajapaksas went ahead with ACSA, in spite of strong opposition from some of its partners. In fact, they did not even bother to ask or take up the issue at Cabinet level before the then Defence Secretary Gotabaya Rajapaksa, a US citizen at the time, and US Ambassador here Robert O. Blake signed it. Close on the heels of the ACSA signing, the US provided specific intelligence that allowed the Sri Lanka Navy to hunt down four floating LTTE arsenals. Whatever critics say, that US intervention ensured the total disruption of the LTTE supply line and the collapse of their conventional fighting capacity by March 2009. The US favourably responded to the then Vice Admiral Wasantha Karannagoda’s request for help and the passing of intelligence was not in any way in line with ACSA.

That agreement covered the 2007 to 2017 period. The Yahapalana government extended it. Yahapalana partners, the SLFP and UNP, never formally discussed the decision to extend the agreement though President Maithripala Sirisena made a desperate attempt to distance himself from ACSA.

It would be pertinent to mention that the US had been pushing for ACSA during Rail Wickremesinghe’s tenure as the Premier, in the 2001-2003 period. But, he lacked the strength to finalise that agreement due to strong opposition from the then Opposition. During the time the Yahapalana government extended ACSA, the US also wanted the Status of Forces Agreement (SOFA) signed. SOFA, unlike ACSA, is a legally binding agreement that dealt with the deployment of US forces here. However, SOFA did not materialise but the possibility of the superpower taking it up cannot be ruled out.

Gotabaya Rajapaksa, who won the 2019 presidential election, earned the wrath of the US for declining to finalise MCC (Millennium Challenge Corporation) Compact on the basis of Prof. Gunaruwan Committee report that warned that the agreement contained provisions detrimental to national security, sovereignty, and the legal system. In the run up to the presidential election, UNP leader Ranil Wickremesinghe declared that he would enter into the agreement in case Sajith Premadasa won the contest.

Post-Aragalaya setup

Since the last presidential election held in September 2024, Admiral Steve Koehler, a four-star US Navy Admiral and Commander of the US Pacific Fleet visited Colombo twice in early October 2024 and February this year. Koehler’s visits marked the highest-level U.S. military engagement with Sri Lanka since 2021.

Between Koehler’s visits, the United States and Sri Lanka signed a Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) formalising the defence partnership between the Montana National Guard, the US Coast Guard District 13, and the Sri Lanka Armed Forces under the Department of War’s State Partnership Programme (SPP). The JVP-led NPP government seems sure of its policy as it delayed taking a decision on one-year moratorium on all foreign research vessels entering Sri Lankan waters though it was designed to block Chinese vessels. The government is yet to announce its decision though the ban lapsed on December 31, 2024.

The then President Ranil Wickremesinghe was compelled to announce the ban due to intense US-Indian pressure.

The incumbent dispensation’s relationship with US and India should be examined against allegations that they facilitated ‘Aragalaya’ that forced President Gotabaya Rajapaksa out of office. The Trump administration underscored the importance of its relationship with Sri Lanka by handing over ex-US Coast Guard Cutter ‘Decisive ‘to the Sri Lanka Navy. The vessel, commanded by Captain Gayan Wickramasooriya, left Baltimore US Coast Guard Yard East Wall Jetty on February 23 and is expected to reach Trincomalee in the second week of May.

Last year Sri Lanka signed seven MoUs, including one on defence and then sold controlling shares of the Colombo Dockyard Limited (CDL) to a company affiliated to the Defence Ministry as New Delhi tightened its grip.

Sri Lanka-US relations seemed on track and the IRIS Dena incident is unlikely to distract the two countries. The US continues to take extraordinary measures to facilitate war on Iran. In a bid to overcome the Iranian blockade on crude carriers the US temporarily eased sanctions to allow India to buy Russian oil.

Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent declared a 30-day waiver was a “deliberate short-term measure” to allow oil to keep flowing in the global market. The US sanctioned Russian oil following Moscow’s invasion of Ukraine, forcing buyers to seek alternatives.

The US doesn’t care about the Ukraine government that must be really upset about the unexpected development. India was forced to halt buying Russian oil and now finds itself in a position to turn towards Russia again. But that would be definitely at the expense of Iran facing unprecedented military onslaught.

By Shamindra Ferdinando

Midweek Review

A Living Legend of the Peradeniya Tradition:

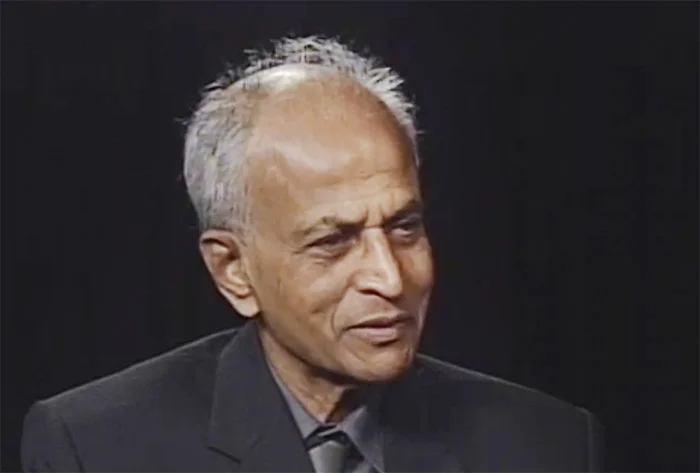

A Tribute to Professor H. L. Seneviratne – Part I

My earliest memories of the eminent anthropologist, Professor H. L. Seneviratne date back to my childhood, when I first encountered his name through the vivid accounts of campus life shared by my late brother, Sugathapala de Silva, then a lecturer in the Department of Sinhala at the University of Peradeniya. By the time I became a first-year sociology student in 1968/69, I had the privilege of being taught by the Professor, whose guidance truly paved the way for my own progression in sociology and anthropology. Even then, it was clear that he was a towering presence—not just as an academician, but as a central figure in the lively cultural and literary renaissance that defined that era of the university’s intellectual history.

H.L. Seneviratne stood alongside a galaxy of intellectuals who shaped and developed the literary consciousness of the Peradeniya University. His professorial research made regular appearances in journals such as Sanskriti and Mimamsa, published Sinhala and English articles, and served as channels for the dissemination of the literary consciousness of Peradeniya to the population at large. These texts were living texts of a dynamic intellectual ferment where the synthesis of classical aesthetic sensibilities with current critical intellectual thought in contemporary Sri Lanka was under way.

The concept of a ‘Peradeniya tradition or culture’, a term which would later become legendary in Sri Lankan literary and intellectual circles, was already being formed at this time. Peradeniya culture came to represent a distinctive synthesis: cosmopolitanism entwined with well-rooted local customs, aesthetic innovation based on classical Sinhala styles, and critical interaction with modernity. Among its pre-eminent practitioners were intellectual giants such as Ediriweera Sarachchandra, Gunadasa Amarasekara, and Siri Gunasinghe. These figures and H.L. Seneviratne himself, were central to the shaping of a space of cultural and literary critique that ranged from newspapers to book-length works, public speeches to theatrical performance.

Unlimited influence

H.L. Seneviratne’s influence was not limited to the printed page, which I discuss in this article. He operated in and responded to the performative, interactive space of drama and music, situating lived artistic practice in his cultural thought. I recall with vividness the late 1950s, a period seared into my memory as one of revelation, when I as a child was fortunate enough to witness one of the first performances of Maname, the trailblazing Sinhala drama that revolutionised Sri Lankan theatre. Drawn from the Nadagam tradition and staged in the open-air theatre in Peradeniya—now known as Sarachchandra Elimahan Ranga Pitaya—or Wala as used by the campus students. Maname was not so much a play as a culturally transformative experience.

H.L. Seneviratne was not just an observer of this change. He joined the orchestra of Maname staged on November 3, 1956, lending his voice and presence to the collective heartbeat of the performance. He even contributed to the musical group by playing the esraj, a quiet but vital addition to the performance’s beauty and richness. Apart from these roles, he played an important part in the activities of Professor Sarathchandra’s Sinhala Drama Society, a talent nursery and centre for collaboration between artists and intellectuals. H.L. Seneviratne was a friend of Arthur Silva, a fellow resident of Arunachalam Hall then, and the President of the Drama Circle. H.L. Seneviratne had the good fortune to play a role, both as a member of the original cast, and an active member of the Drama Circle that prevailed on lecturer E.R. Sarathchandra to produce a play and gave him indispensable organizational support. It was through this society that Sarachchandra attracted some of the actors who brought into being Maname and later Sinhabhahu, plays which have become the cornerstone of Sri Lanka’s theatrical heritage.

The best chronicler of Maname

H.L. Seneviratne is the best chronicler of Maname. (Towards a National Art, From Home and the World, Essays in honour of Sarath Amunugama. Ramanika Unamboowe and Varuni Fernando (eds)). He chronicles the genesis of Ediriweera Sarachchandra’s seminal play Maname, framing it as a pivotal attempt to forge a sophisticated national identity by synthesizing indigenous folk traditions with Eastern theatrical aesthetics. Seneviratne details how Sarachchandra, disillusioned with the ‘artificiality’ of Western-influenced urban theatre and the limitations of both elite satires and rural folk plays, looked toward the Japanese Noh and Kabuki traditions to find a model for a ‘national’ art that could appeal across class divides. The author emphasises that the success of Maname was not merely a solo intellectual feat but a gruelling, collective effort involving a ‘gang of five’ academics and a dedicated cohort of rural, bilingual students from the University of Ceylon at Peradeniya. Through anecdotes regarding the discovery of lead actors like Edmund Wijesinghe and the assembly of a unique orchestra, Seneviratne highlights the logistical struggles—from finding authentic instruments to managing cumbersome stage sets—that ultimately birthed a transformative ‘oriental’ theatre rooted in the nadagama style yet refined for a modern, sophisticated audience.

Born in Sri Lanka in 1934, in a village in Horana, he was educated at the Horana Taxila College following which he was admitted to the Department of Sociology at the University of Peradeniya. H.L. Seneviratne’s academic journey subsequently led him to the University of Rochester for his doctoral studies. But, despite his long tenure in the United States, his research has remained firmly rooted in the soil of his homeland.

His early seminal work, Rituals of the Kandyan State, his PhD thesis turned into a book, offered a groundbreaking analysis of the Temple of the Tooth (Dalada Maligawa). By examining the ceremonies surrounding the sacred relic, H.L. Seneviratne demonstrated how religious performance served as the bedrock of political legitimacy in the Kandyan Kingdom. He argued that these rituals at the time of his fieldwork in the early 1970s were not static relics of the past, but active tools used to construct and maintain the authority of the state, the ideas that would resonate throughout his later career.

The Work of Kings

Perhaps, his most provocative contribution arrived with the publication of The Work of Kings published in 1999. In this sweeping study, H.L. Seneviratne traced the transformation of the Buddhist clergy, or Sangha, from the early 20th-century ‘social service’ monks, who focused on education and community upliftment, to the more politically charged nationalist figures of the modern era. He analysed the shift away from a universalist, humanistic Buddhism toward a more exclusionary identity, sparking intense debate within both academic and religious circles in Sri Lanka.

In The Work of Kings, H.L. Seneviratne has presented a sophisticated critique and argued that in the early 20th century, influenced by figures like Anagarika Dharmapala, there was a brief ‘monastic ideal’ centred on social service and education. This period saw monks acting as catalysts for community development and moral reform embodying a humanistic version of Buddhism that sought to modernize the country while maintaining its spiritual integrity.

However, H.L. Seneviratne contends that this situation was eventually derailed by the rise of post-independence nationalism. He describes a process where the clergy moved away from universalist goals to become the vanguard of a narrow ethno-religious identity. By aligning themselves so closely with the state and partisan politics, H.L. Seneviratne suggests that the Sangha inadvertently traded their moral authority for political influence. This shift, in his view, led to the ‘betrayal’ of the original social service movement, replacing a vision of broad social progress with one centred on political dominance.

The core of his critique lies in the disappearance of what he calls the ‘intellectual monk.’ He laments the decline of the scholarly, reflective tradition in favour of a more populist and often inflammatory rhetoric. By analysing the rhetoric of key monastic figures, H.L. Senevirathne illustrates how the language of Buddhism was repurposed to justify political ends, often at the expense of the pluralistic values that he believes are inherent to the faith’s core teachings.

H.L. Seneviratne’s work remains highly relevant today as it provides a framework for understanding contemporary religious tensions. His analysis serves as a warning about the consequences of merging religious institutional power with state politics. By documenting this historical shift, he challenges modern Sri Lankans—and global observers—to reconsider the role of religious institutions in a secular, democratic state, urging a return to the compassionate and socially inclusive roots of the Buddhist tradition.

Within the broader context of Sri Lankan anthropology, H.L. Seneviratne is frequently grouped with other towering figures of his generation, most notably Stanley Jeyaraja Tambiah and Gananath Obeyesekere. Together, this remarkable cohort revolutionized the study of Sri Lanka by applying structural and psychological analyses to religious and ethnic identity. While Tambiah famously interrogated the betrayal of non-violent Buddhist principles in the face of political violence, H.L. Seneviratne’s work is often seen as the essential sociological counterpart, providing the detailed historical and institutional narrative of how the monastic order itself was reshaped by these very forces.

Reation to Seneviratne’s critque

The reaction to H.L. Seneviratne’s critique has been as multifaceted as the work itself. In academic circles, particularly those influenced by post-colonial theory, he is celebrated for speaking truth in a public place. Scholars have noted that because he writes as an insider—both a Sinhalese and a Buddhist, that makes them both credible and, to some, highly objectionable. His work has paved the way for a younger generation of Sri Lankan sociologists and anthropologists to move beyond traditional functionalism towards more radical articulations of competing interests and political power.

However, his analysis has also made him a target for nationalist critics. Those aligned with ethno-religious movements often view his deconstruction of the Sangha’s political role as an attack on Sinhalese-Buddhist identity itself. These detractors argue that H.L. Seneviratne’s intellectualist or universalist view of Buddhism fails to account for the necessity of the clergy’s role in protecting the nation against neo colonial and modern pressures. This tension highlights the very descent into ideology that H.L. Seneviratne has spent his career documenting.

H.L. Seneviratne’s legacy is defined by this ongoing dialogue between scholarship and social reality. His transition from the detached scholar seen in his early work on Kandyan rituals to the socially concerned intellectual of The Work of Kings mirrors the very transformation of the Sangha and Buddha Sasana he studied. By refusing to look away from the complexities of the present, he has ensured that his work remains a cornerstone for any serious discussion on the future of religion and governance in Sri Lanka.

Focus on good governance

In his later years, H.L. Seneviratne has pivoted his focus toward the practical application of his theories, specifically examining how the concept of ‘Good Governance’ interacts with traditional religious structures. He argues that for Sri Lanka to achieve true stability, there must be a fundamental reimagining of the Sangha’s role in the public sphere—one that moves away from the ‘work of Kings’ and returns to a more ethical, advisory capacity. This shift in his recent lectures reflects a deep concern about the erosion of democratic institutions and the way religious sentiment can be harnessed to bypass the rule of law.

Building on this, contemporary scholars like Benjamin Schonthal have expanded H.L. Seneviratne’s inquiry into the legal and constitutional dimensions of Buddhism in Sri Lanka. While H.L. Seneviratne provided the anthropological groundwork for how monks gained political power, this newer generation of academics examines how that power has been codified into the very laws of the state. They explore the ‘path dependency’ created by the historical shifts H.L. Seneviratne documented, looking at how the legal privileging of Buddhism creates unique challenges for a pluralistic society.

New Sangha

Furthermore, his influence is visible in the work of local scholars who focus on ‘engaged Buddhism.’ These researchers look back at H.L. Seneviratne’s description of the early 20th-century social service monks as a blueprint for modern reform. By identifying the moment where the clergy’s mission shifted from social welfare to political nationalism, these scholars use H.L. Seneviratne’s historical milestones to advocate a ‘New Sangha’ that prioritizes reconciliation and inter-ethnic harmony over state-aligned power.

The enduring power of H.L. Seneviratne’s work lies in its refusal to offer easy answers. By mapping the transition within Buddhist practice from ritual to politics, and from social service to nationalism, he has provided an analytical framework in which the nation can see its own transformation. His legacy is not just a collection of books, but a persistent, rigorous habit of questioning that continues to inspire those who seek to understand the delicate balance between faith and the modern state.

H.L. Seneviratne continues to challenge his audience to think beyond the immediate political moment. By documenting the arc of Sri Lankan history from the sacred rituals of the Kandyan kings to the modern halls of parliament, he provides a vital sense of perspective. Whether he is being celebrated by the academic community or critiqued by nationalist voices, his work ensures that the conversation regarding the soul of the nation remains rigorous, historically grounded, and unafraid of its own complexities.

Anthropology and cinema

H.L. Seneviratne identifies the mid-1950s as the critical turning point for this cinematic shift, specifically anchoring the move to 1956 with the release of Lester James Peries’s “Rekava.” This period was a watershed moment in Sri Lankan history, coinciding with a broader nationalist resurgence that sought to reclaim a localized identity from the influence of colonial and foreign powers. H.L. Seneviratne suggests that before this era, the ‘South Indian formula’ dominated the screen, characterized by studio-bound sets, theatrical acting, and musical interludes that felt alien to the island’s actual social fabric. The pioneers of this movement, led by Lester James Peries and later followed by figures like Siri Gunasinghe in the early 1960s, deliberately moved the camera into the open air of the rural village to capture what H.L. Seneviratne describes as the ‘authentic rhythms’ of life. This transition was not merely aesthetic but deeply ideological; it replaced the mythical, exaggerated heroism of commercial cinema with a nuanced exploration of the post-colonial middle class and the crumbling feudal hierarchies. By the 1960s, through landmark works like ‘Gamperaliya,’ these filmmakers were successfully crafting a modern mythology that reflected the internal psychological tensions and the social evolution of a nation navigating its way between traditional Buddhist values and a rapidly modernizing world.

His critique of the relationship between art and the state is particularly evident in his analysis of historical epics, where he has argued that certain cinematic portrayals of ancient kings and battles serve as a form of ‘visual nationalism,’ translating the ideological shifts he documented in The Work of Kings onto the silver screen. By analysing these films, he shows how popular culture can become a powerful tool for constructing a simplified, heroic past that often ignores the multi-ethnic and pluralistic realities of the island’s history.

(To be concluded)

by Professor M. W. Amarasiri de Silva

Midweek Review

The Loneliness of the Female Head

The years have painfully trudged on,

But she’s yet to have answers to her posers;

What became of her bread-winning husband,

Who went missing amid the heinous bombings?

When is she being given a decent stipend,

To care for her daughter wasting-away in leprosy?

Who will help keep her hearth constantly burning,

Since work comes only in dribs and drabs?

And equally vitally, when will they stop staring,

As if she were the touch-me-not of the community?

By Lynn Ockersz

-

News7 days ago

News7 days agoPeradeniya Uni issues alert over leopards in its premises

-

News5 days ago

News5 days agoRepatriation of Iranian naval personnel Sri Lanka’s call: Washington

-

News7 days ago

News7 days agoWife raises alarm over Sallay’s detention under PTA

-

Features5 days ago

Features5 days agoWinds of Change:Geopolitics at the crossroads of South and Southeast Asia

-

News4 days ago

News4 days agoProf. Dunusinghe warns Lanka at serious risk due to ME war

-

Sports3 days ago

Sports3 days agoRoyal start favourites in historic Battle of the Blues

-

Latest News7 days ago

Latest News7 days agoHeat Index at ‘Caution Level’ in the Sabaragamuwa province and, Colombo, Gampaha, Kurunegala, Anuradhapura, Vavuniya, Hambanthota and Monaragala districts

-

Sports2 days ago

Sports2 days agoThe 147th Royal–Thomian and 175 Years of the School by the Sea