Features

A wistful reflection of times past

The Colombo Medical School batch of 1962

By Dr Nihal D Amerasekera

“Friendship is the hardest thing in the world to explain. It’s not something you learn in school. But if you haven’t learned the meaning of friendship, you really haven’t learned anything.” — Muhammad Ali

Remembering Medical School and friends takes me back to my roots and those distant days. I am deluged by a deep sense of déjà vu as I time travel to the 1960’s. Those of us who live abroad may see those early days in a certain fuzzy sepia light. But our emotional attachment remains undiminished. The quiet Kynsey road, the familiar façade of the grey administrative building and the sentinel Clocktower stand unchanged. I am simply mesmerised by the elegant sweep of those majestic buildings. In that dreamy state it is so easy to be enchanted by the constant whirr of the Vespas in the dusty parking bay behind the Milk Booth and be overwhelmed by the smell of smoke that fills the air. In our mind’s eye the faculty will always remain as we left it in 1967.

We were a batch of around 150 students and in those days the faculty of Medicine felt like an enclave of privilege, and it was. Entry into the Faculty was the culmination of years of toil and sacrifice. We still had the security of home and our parents paid the bills. There was such a great sense of myopic optimism, we lost ourselves in the adulation. We dreamed it was our passport to fame and fortune. The idyll soon faded as the harsher truths of real life intruded. Life being like a game of snakes and ladders, always has ways to end that utopian vision and bring us back to reality!!

The Faculty was our Temple of Wisdom and also our gilded cage. There was an air of confidence and a touch of vanity which came from being a medical student. Life then was a dream. I developed a sinister arrogance and an assured sense of entitlement. I dreamed of living happily ever after. It was not long before part of that charm and fantasy began to wear thin.

The common room with the canteen was the social hub of the faculty and a very special place. That was our own retreat and shelter from the storms of faculty life. Many friendships were made and firmed within those walls. It was a vital place, where we could gather informally to talk, gossip and pass the time. Racy jokes and saucy humour filled the air. We gathered there to listen to music, play billiards, table tennis and carrom. Cupid was actively busy slinging his arrows in the faculty. The canteen was a haven for couples to whisper those ‘sweet nothings’.

There were evening sing-songs in the common room. These were ever so popular and simply unforgettable. I can still feel its pleasure, hear them sing and even picture the dancing. The echoes of our communal past litter our memories. After the passage of half a century much of faculty life has changed. The lively and vibrant common room with its unique ambience would now seem like a dream from a lost world. A dream that can only exist in our memories.

The stormy dynamics of the ‘Block’ were a baptism of fire. Detailed study of anatomy, physiology and biochemistry filled our days and nights. We were weighed down by signatures and revisals that generated a toxic atmosphere. But there were the Colours Nights and Block Nights to imbibe the spirit of the swinging sixties and liven up our lives. There was also a certain wildness, colourful antics and downright mischief that was associated with being a medical student. Sometimes this badness and madness became tabloid fodder. We did transgress the red line and pay the price. The good, bad and the ugly are well described and documented in the faculty chronicles. Despite our occasional rascality we were blessed with a sympathetic public image.

Then we embarked on our jagged path from the dissection rooms to the ward classes and clinical appointments across Kynsey Road. My abiding memory of those years are the long walks along those airy hospital corridors in search of patients and knowledge. We strolled like a ‘peacocks’, swinging those knee hammers and proudly wearing the stethoscopes around our necks. Meanwhile in the third and fourth year we had a profusion of subjects to comprehend. I still convulse thinking of the sheer volume of facts we had to commit to memory. From all that knowledge what remains now are the daringly prophetic lines of a poem from Clinical Pharmacology by D.R Laurence:

“Doctor, goodbye, my sail’s unfurl’d, I’m off to try the other world”.

We were immensely fortunate to belong to a generation taught by a plethora of dedicated and gifted teachers. Like us many called it the Golden Era of Medical Education. Under their influence and tutelage life was not always a bed of roses. In the ward classes and teaching appointments there were some exchanges too painful to recall. Although seemingly omniscient and more than a tad egocentric, they inspired us. They gave of their best to the students. We remember with affection and gratitude the dedication and commitment of our clinical teachers, professors and lecturers on this our special day.

Then like a never-ending storm came the Final Examination. Seeing the name on the notice board was an iconic moment to savour. Success is where preparation and opportunity meet. Success was also our liberation and the passport to freedom. From the glowing embers of those undergrad years a new era was born.

“Go West young man” was the mantra that appealed to many. The political turmoil and our sagging economy did not give us much faith or hope. One of the greatest triumphs in life is to pursue one’s dreams. Many dispersed far and wide in search of work and opportunity. Those who left the country entered the Darwinian struggle of survival of the fittest. Amidst the fierce competition for the plum jobs, there were the many unwanted prejudices to contend with.

The many who remained in Sri Lanka reached the top of their careers in the fullness of time. I acknowledge the patriotism, loyalty and resilience of those who remained in the motherland to serve the country. They lived through some difficult times. The émigrés too played their role professionally to serve society and the communities wherever they lived and worked. Those who lived abroad made donations to a multitude of Sri Lankan charities. They also provided financial support to Medical institutions and Medical education back home.

I would like the achievements of our batch to be remembered as one of the most successful. I am delighted in the academic accomplishments and the professional success of our batch-mates. Although I loved it, mine was a career mixed with grit and glamour in equal measure.

We stepped on the treadmill to carve ourselves a career. Then marriage and caring for our families took precedence. We embraced and adored everything parenthood had to offer. Time passed swiftly and relentlessly. With the passage of years, we met our batch-mates infrequently at reunions. The endless vicissitudes of life have usurped our youth. Our long and demanding professional lives gradually came to a halt. Retirement is not the end but a new beginning. Still sprightly, we hit the golf greens and continue to entertain grandkids as life meanders slowly along. We are now more at peace with our lot in life.

Fast forward to 2022, we are now living on borrowed time. Despite all that sweating and grunting in the gym, we will leave our earthly abode one by one. On this our special Day we unite across faiths, ethnicity and backgrounds to remember our dear departed friends. Despite the mosaic of grief that engulfs us remembering departed friends, we hold back on our grieving. Let the silence and stillness reflect and capture the moment. As a group, we remember and celebrate their lives. There are some with whom we have associated more closely. For them it is much harder to banish the feelings of pain, despite the years. There is a wish to capture the essence of the character of our friends to recall the good times. They indeed have left behind “Footprints on the sands of time”.

We have all lost close friends from the batch. As we remember them, the inevitable regrets will surface too. We could have done much more to meet or to be in touch. Those joyful memories too will fade as we age. So let us cherish and treasure them now.

I take this opportunity to remember our friends who are battling through with dementia or now in long term or terminal care. It is our wish they will remain comfortable in their time on earth and continue to receive the love and care they so richly deserve.

I recall the wisdom of Robert Louis Stevenson: “we are all travellers in the wilderness of the world and the best we can do is to find an honest friend”. So thankful we found so many.

From the faculty staff I chose to pay homage to Prof O.E.R Abhayaratne, the Professor of Public Health and the Dean of the Faculty of Medicine. Amusing and widely respected he maintained the prestige and esteem of the institution as the Dean of the Faculty in a rapidly changing political milieu. Well known for his administrative strengths, by his charm and charisma, he was able to harness the support of some eccentric and egocentric professors and lecturers. His tenure was characterised by his generosity, kindness and sense of humour. The Profs delightfully poetic lectures lit up our Public Health education and also our lives. When we were in trouble after the Castle Street incident, he saved our careers from ruin. While maintaining his dignity and decorum he graced our Block Nights and supported the clean fun we had in the Men’s Common Room.

Larger than life and the monarch of all he surveyed we couldn’t have had a better “Boss”. His sartorial elegance or lack of it, eccentricities, mannerisms and idiosyncrasies have entered the folklore of this great institution. He was so much a part of our lives and of the Faculty of Medicine, his familiar stentorian voice must swirl in the ether of its corridors of power. May his Soul Rest in Peace.

From the dazzling firmament of fine clinical teachers, I choose to pay tribute to Dr.Darrell Weinman. His ward classes were conducted in a room at the Neuro Surgical Unit which was always packed to the rafters with students. With his mercurial personality Dr Weinman inspired, motivated and entertained us. He thrived on the intrigue and captivated us by the way he extracted relevant diagnostic information from patients. Dr Weinman in his theatrical performances played Sherlock Holmes to unravel the mystery and arrive at a diagnosis. His effortless erudition made whole swathes of impenetrable knowledge seem so accessible.

We bowed to his brilliance. He was such a kind man in the pernicious environment of medical education of the time. He treated the students with respect and in turn was held in great awe and esteem. Darrell Weinman had it all – handsome, a fine cricketer, brilliant scholar and a superb neurosurgeon. But these provide no protection from the frailties of human life and the awesome force of destiny. Sadly, when at the height of his fame, fate intervened. Dr Weinman emigrated to Australia. This was a great shock to us all and an enormous loss to Sri Lanka. He gave up his beloved neurosurgery to work in general practice in Sydney. There he was known for his kindness and compassion and was well liked and highly regarded by his patients. Darrell Weinman passed away in 2018. Requiescat in pace

Despite the crowded candles on the birthday cake, some of us are more resilient to ageing than others. But the main problem is that gravity takes over our lives and the body never allow us to forget the passage of years. There are now a multitude of well-heeled pathways to a longer life. A sad consequence of living long is that you have to say goodbye to a lot of people you care about. By now we have all learnt to live with this. We still have much to enjoy. As we end our life’s fandango, those glorious and treasured undergraduate years will always remain “misty watercolour memories, of the way we were”.

“Look not mournfully into the past, it comes not back again. Wisely improve the present, it is thine. Go forth to meet the shadowy future without fear and with a manly heart”.

Henry Wadsworth Longfellow

Features

Ranking public services with AI — A roadmap to reviving institutions like SriLankan Airlines

Efficacy measures an organisation’s capacity to achieve its mission and intended outcomes under planned or optimal conditions. It differs from efficiency, which focuses on achieving objectives with minimal resources, and effectiveness, which evaluates results in real-world conditions. Today, modern AI tools, using publicly available data, enable objective assessment of the efficacy of Sri Lanka’s government institutions.

Among key public bodies, the Supreme Court of Sri Lanka emerges as the most efficacious, outperforming the Department of Inland Revenue, Sri Lanka Customs, the Election Commission, and Parliament. In the financial and regulatory sector, the Central Bank of Sri Lanka (CBSL) ranks highest, ahead of the Securities and Exchange Commission, the Public Utilities Commission, the Telecommunications Regulatory Commission, the Insurance Regulatory Commission, and the Sri Lanka Standards Institution.

Among state-owned enterprises, the Sri Lanka Ports Authority (SLPA) leads in efficacy, followed by Bank of Ceylon and People’s Bank. Other institutions assessed included the State Pharmaceuticals Corporation, the National Water Supply and Drainage Board, the Ceylon Electricity Board, the Ceylon Petroleum Corporation, and the Sri Lanka Transport Board. At the lower end of the spectrum were Lanka Sathosa and Sri Lankan Airlines, highlighting a critical challenge for the national economy.

Sri Lankan Airlines, consistently ranked at the bottom, has long been a financial drain. Despite successive governments’ reform attempts, sustainable solutions remain elusive.

Globally, the most profitable airlines operate as highly integrated, technology-enabled ecosystems rather than as fragmented departments. Operations, finance, fleet management, route planning, engineering, marketing, and customer service are closely coordinated, sharing real-time data to maximise efficiency, safety, and profitability.

The challenge for Sri Lankan Airlines is structural. Its operations are fragmented, overly hierarchical, and poorly aligned. Simply replacing the CEO or senior leadership will not address these deep-seated weaknesses. What the airline needs is a cohesive, integrated organisational ecosystem that leverages technology for cross-functional planning and real-time decision-making.

The government must urgently consider restructuring Sri Lankan Airlines to encourage:

=Joint planning across operational divisions

=Data-driven, evidence-based decision-making

=Continuous cross-functional consultation

=Collaborative strategic decisions on route rationalisation, fleet renewal, partnerships, and cost management, rather than exclusive top-down mandates

Sustainable reform requires systemic change. Without modernised organisational structures, stronger accountability, and aligned incentives across divisions, financial recovery will remain out of reach. An integrated, performance-oriented model offers the most realistic path to operational efficiency and long-term viability.

Reforming loss-making institutions like Sri Lankan Airlines is not merely a matter of leadership change — it is a structural overhaul essential to ensuring these entities contribute productively to the national economy rather than remain perpetual burdens.

By Chula Goonasekera – Citizen Analyst

Features

Why Pi Day?

International Day of Mathematics falls tomorrow

The approximate value of Pi (π) is 3.14 in mathematics. Therefore, the day 14 March is celebrated as the Pi Day. In 2019, UNESCO proclaimed 14 March as the International Day of Mathematics.

Ancient Babylonians and Egyptians figured out that the circumference of a circle is slightly more than three times its diameter. But they could not come up with an exact value for this ratio although they knew that it is a constant. This constant was later named as π which is a letter in the Greek alphabet.

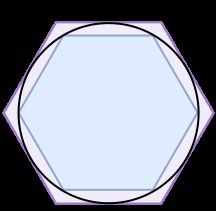

It was the Greek mathematician Archimedes (250 BC) who was able to find an upper bound and a lower bound for this constant. He drew a circle of diameter one unit and drew hexagons inside and outside the circle such that the sides of each hexagon touch the sides of the circle. In mathematics the circle passing through all vertices of a polygon is called a ‘circumcircle’ and the largest circle that fits inside a polygon tangent to all its sides is called an ‘incircle’. The total length of the smaller hexagon then becomes the lower bound of π and the length of the hexagon outside the circle is the upper bound. He realised that by increasing the number of sides of the polygon can make the bounds get closer to the value of Pi and increased the number of sides to 12,24,48 and 60. He argued that by increasing the number of sides will ultimately result in obtaining the original circle, thereby laying the foundation for the theory of limits. He ended up with the lower bound as 22/7 and the upper bound 223/71. He could not continue his research as his hometown Syracuse was invaded by Romans and was killed by one of the soldiers. His last words were ‘do not disturb my circles’, perhaps a reference to his continuing efforts to find the value of π to a greater accuracy.

Archimedes can be considered as the father of geometry. His contributions revolutionised geometry and his methods anticipated integral calculus. He invented the pulley and the hydraulic screw for drawing water from a well. He also discovered the law of hydrostatics. He formulated the law of levers which states that a smaller weight placed farther from a pivot can balance a much heavier weight closer to it. He famously said “Give me a lever long enough and a place to stand and I will move the earth”.

Mathematicians have found many expressions for π as a sum of infinite series that converge to its value. One such famous series is the Leibniz Series found in 1674 by the German mathematician Gottfried Leibniz, which is given below.

π = 4 ( 1 – 1/3 + 1/5 – 1/7 + 1/9 – ………….)

The Indian mathematical genius Ramanujan came up with a magnificent formula in 1910. The short form of the formula is as follows.

π = 9801/(1103 √8)

For practical applications an approximation is sufficient. Even NASA uses only the approximation 3.141592653589793 for its interplanetary navigation calculations.

It is not just an interesting and curious number. It is used for calculations in navigation, encryption, space exploration, video game development and even in medicine. As π is fundamental to spherical geometry, it is at the heart of positioning systems in GPS navigations. It also contributes significantly to cybersecurity. As it is an irrational number it is an excellent foundation for generating randomness required in encryption and securing communications. In the medical field, it helps to calculate blood flow rates and pressure differentials. In diagnostic tools such as CT scans and MRI, pi is an important component in mathematical algorithms and signal processing techniques.

This elegant, never-ending number demonstrates how mathematics transforms into practical applications that shape our world. The possibilities of what it can do are infinite as the number itself. It has become a symbol of beauty and complexity in mathematics. “It matters little who first arrives at an idea, rather what is significant is how far that idea can go.” said Sophie Germain.

Mathematics fans are intrigued by this irrational number and attempt to calculate it as far as they can. In March 2022, Emma Haruka Iwao of Japan calculated it to 100 trillion decimal places in Google Cloud. It had taken 157 days. The Guinness World Record for reciting the number from memory is held by Rajveer Meena of India for 70000 decimal places over 10 hours.

Happy Pi Day!

The author is a senior examiner of the International Baccalaureate in the UK and an educational consultant at the Overseas School of Colombo.

by R N A de Silva

Features

Sheer rise of Realpolitik making the world see the brink

The recent humanly costly torpedoing of an Iranian naval vessel in Sri Lanka’s Exclusive Economic Zone by a US submarine has raised a number of issues of great importance to international political discourse and law that call for elucidation. It is best that enlightened commentary is brought to bear in such discussions because at present misleading and uninformed speculation on questions arising from the incident are being aired by particularly jingoistic politicians of Sri Lanka’s South which could prove deleterious.

The recent humanly costly torpedoing of an Iranian naval vessel in Sri Lanka’s Exclusive Economic Zone by a US submarine has raised a number of issues of great importance to international political discourse and law that call for elucidation. It is best that enlightened commentary is brought to bear in such discussions because at present misleading and uninformed speculation on questions arising from the incident are being aired by particularly jingoistic politicians of Sri Lanka’s South which could prove deleterious.

As matters stand, there seems to be no credible evidence that the Indian state was aware of the impending torpedoing of the Iranian vessel but these acerbic-tongued politicians of Sri Lanka’s South would have the local public believe that the tragedy was triggered with India’s connivance. Likewise, India is accused of ‘embroiling’ Sri Lanka in the incident on account of seemingly having prior knowledge of it and not warning Sri Lanka about the impending disaster.

It is plain that a process is once again afoot to raise anti-India hysteria in Sri Lanka. An obligation is cast on the Sri Lankan government to ensure that incendiary speculation of the above kind is defeated and India-Sri Lanka relations are prevented from being in any way harmed. Proactive measures are needed by the Sri Lankan government and well meaning quarters to ensure that public discourse in such matters have a factual and rational basis. ‘Knowledge gaps’ could prove hazardous.

Meanwhile, there could be no doubt that Sri Lanka’s sovereignty was violated by the US because the sinking of the Iranian vessel took place in Sri Lanka’s Exclusive Economic Zone. While there is no international decrying of the incident, and this is to be regretted, Sri Lanka’s helplessness and small player status would enable the US to ‘get away with it’.

Could anything be done by the international community to hold the US to account over the act of lawlessness in question? None is the answer at present. This is because in the current ‘Global Disorder’ major powers could commit the gravest international irregularities with impunity. As the threadbare cliché declares, ‘Might is Right’….. or so it seems.

Unfortunately, the UN could only merely verbally denounce any violations of International Law by the world’s foremost powers. It cannot use countervailing force against violators of the law, for example, on account of the divided nature of the UN Security Council, whose permanent members have shown incapability of seeing eye-to-eye on grave matters relating to International Law and order over the decades.

The foregoing considerations could force the conclusion on uncritical sections that Political Realism or Realpolitik has won out in the end. A basic premise of the school of thought known as Political Realism is that power or force wielded by states and international actors determine the shape, direction and substance of international relations. This school stands in marked contrast to political idealists who essentially proclaim that moral norms and values determine the nature of local and international politics.

While, British political scientist Thomas Hobbes, for instance, was a proponent of Political Realism, political idealism has its roots in the teachings of Socrates, Plato and latterly Friedrich Hegel of Germany, to name just few such notables.

On the face of it, therefore, there is no getting way from the conclusion that coercive force is the deciding factor in international politics. If this were not so, US President Donald Trump in collaboration with Israeli Rightist Premier Benjamin Natanyahu could not have wielded the ‘big stick’, so to speak, on Iran, killed its Supreme Head of State, terrorized the Iranian public and gone ‘scot-free’. That is, currently, the US’ impunity seems to be limitless.

Moreover, the evidence is that the Western bloc is reuniting in the face of Iran’s threats to stymie the flow of oil from West Asia to the rest of the world. The recent G7 summit witnessed a coming together of the foremost powers of the global North to ensure that the West does not suffer grave negative consequences from any future blocking of western oil supplies.

Meanwhile, Israel is having a ‘free run’ of the Middle East, so to speak, picking out perceived adversarial powers, such as Lebanon, and militarily neutralizing them; once again with impunity. On the other hand, Iran has been bringing under assault, with no questions asked, Gulf states that are seen as allying with the US and Israel. West Asia is facing a compounded crisis and International Law seems to be helplessly silent.

Wittingly or unwittingly, matters at the heart of International Law and peace are being obfuscated by some pro-Trump administration commentators meanwhile. For example, retired US Navy Captain Brent Sadler has cited Article 51 of the UN Charter, which provides for the right to self or collective self-defence of UN member states in the face of armed attacks, as justifying the US sinking of the Iranian vessel (See page 2 of The Island of March 10, 2026). But the Article makes it clear that such measures could be resorted to by UN members only ‘ if an armed attack occurs’ against them and under no other circumstances. But no such thing happened in the incident in question and the US acted under a sheer threat perception.

Clearly, the US has violated the Article through its action and has once again demonstrated its tendency to arbitrarily use military might. The general drift of Sadler’s thinking is that in the face of pressing national priorities, obligations of a state under International Law could be side-stepped. This is a sure recipe for international anarchy because in such a policy environment states could pursue their national interests, irrespective of their merits, disregarding in the process their obligations towards the international community.

Moreover, Article 51 repeatedly reiterates the authority of the UN Security Council and the obligation of those states that act in self-defence to report to the Council and be guided by it. Sadler, therefore, could be said to have cited the Article very selectively, whereas, right along member states’ commitments to the UNSC are stressed.

However, it is beyond doubt that international anarchy has strengthened its grip over the world. While the US set destabilizing precedents after the crumbling of the Cold War that paved the way for the current anarchic situation, Russia further aggravated these degenerative trends through its invasion of Ukraine. Stepping back from anarchy has thus emerged as the prime challenge for the world community.

-

News6 days ago

News6 days agoPeradeniya Uni issues alert over leopards in its premises

-

News4 days ago

News4 days agoRepatriation of Iranian naval personnel Sri Lanka’s call: Washington

-

News6 days ago

News6 days agoWife raises alarm over Sallay’s detention under PTA

-

Features4 days ago

Features4 days agoWinds of Change:Geopolitics at the crossroads of South and Southeast Asia

-

News3 days ago

News3 days agoProf. Dunusinghe warns Lanka at serious risk due to ME war

-

Latest News6 days ago

Latest News6 days agoHeat Index at ‘Caution Level’ in the Sabaragamuwa province and, Colombo, Gampaha, Kurunegala, Anuradhapura, Vavuniya, Hambanthota and Monaragala districts

-

Sports2 days ago

Sports2 days agoRoyal start favourites in historic Battle of the Blues

-

Features6 days ago

Features6 days agoThe final voyage of the Iranian warship sunk by the US