Features

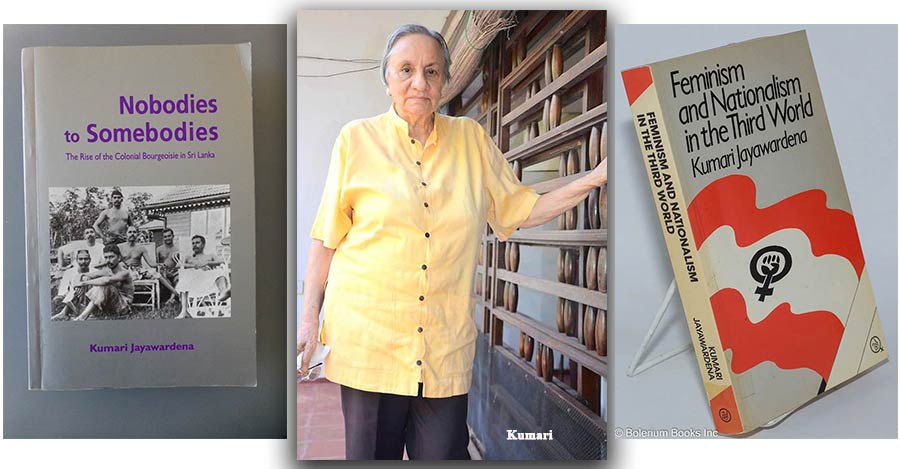

A Tribute to Kumari Jayawardena

By Uditha Devapriya

Mervyn de Silva (1973)

Last month the Collective for Historical Dialogue & Memory (CHDM) organised a screening of Conversations with Kumari, a documentary on Kumari Jayawardena. Last week Jayawardena turned 93. Yesterday I reflected on her and the generation she represented. That generation is leaving us, but it remains as influential as ever.

I then went back to Kalana Senaratne’s brilliant interview of Jayawardena, done by the Social Scientists’ Association nine years ago. Watching it, one is taken aback by the breadth of her interventions. Once in a while I get taken aback too.

Five years ago, after meeting Kanishka Goonewardena at Barefoot, I visited the bookshop with my friend Shiran Illanperuma. Poring through the obligatory coffee table biographies, we came across a copy of Labour, Feminism, and Ethnicity in Sri Lanka.

I remember Shiran commenting, “She never stops writing.” And I remember smiling.

I wasn’t smiling at Shiran’s remark only. I was thinking of the irony of a collection of 30- or 40-year-old essays by the country’s foremost social scientist being sold at a place one hardly associates with such books. For Barefoot is the capital of Sri Lanka’s Bobos. You go there to buy biographies of Geoffrey Bawa, the latest art and culture publications from the National Trust. Kumari Jayawardena’s essays, by contrast, stick out like Gananath Obeyesekere’s – also sold at Barefoot – studies of the doomed king and the Veddas.

But then that is a testament to her contribution, and his. Jayawardena began her career at a particular point in Sri Lanka’s intellectual history. One can’t write about her, or comment on her, without considering the period she worked and lived in. This was after 1956, when the shift to Sinhala and Tamil had emancipated the social sciences from its colonialist shackles. Scholars like Ralph Pieris, and the first generation of Western scholars, like James Brow and Edmund Leach, had made waves in the country.

Jayawardena represented a second generation of social scientists in post-independence Sri Lanka. This generation had been radicalised from an early age, by their families, at school, and most formatively in university. Conversations with Kumari recounts Jayawardena’s encounters in England, where she attended the LSE. In London, she befriended Romila Thapar. The parallels between these two thinkers are striking, but undeniable. Both fell into the company of freethinkers and radicals. Both absorbed the thinking of those radicals. And both applied their modes of analysis upon their return home.

To appreciate Jayawardena’s achievement, it would be pertinent to recall that, by Thapar’s time, India already had a long, rich tradition of Marxist and progressive social scientists. Jayawardena did not have the benefit of this lineage in Sri Lanka. The sole Marxist or overtly leftwing social scientist working in Sri Lanka at the time – Newton Gunasinghe – had only begun his academic career. As Jayadeva Uyangoda has observed in an essay on the man, before Gunasinghe Sri Lankan social scientists tended to operate within a liberal framework. It was left to Gunasinghe, and Jayawardena, to change this.

The intellectual-academic establishment Jayawardena and Gunasinghe encountered in Sri Lanka was highly conservative. It fundamentally bifurcated between a Westernised and a (predominantly Sinhala) nationalist wing. Often these two wings came together. Dayan Jayatilleka’s critique of Sri Lanka’s political bourgeoisie can, in one sense, be levelled at its intellectual bourgeoisie: it was deeply Westernised, but failed to become a modernising, emancipatory force. This is why, and how, apart from R. A. L. H. Gunawardana, Sri Lanka did not produce a politically radical historian. “We never had a Nehru,” Jayatilleka once pointed out. Well, we almost never had a Romila Thapar either.

It would be amiss to say there were no radical scholars before the likes of Gunasinghe. We did. It’s just that they weren’t sociologists or anthropologists by profession. As I have noted in an essay on Gunasinghe, some of the earliest, if not the earliest, anthropological studies of Sri Lanka were authored by Marxist radicals. Hector Abhayavardhana, who wound up as the LSSP’s chief theoretician, along with N. M. Perera and Colvin R. de Silva, looked at, and analysed, Sri Lankan society from a more materialist perspective, providing historians and social scientists in later years with much material. For some reason, this contribution tends not to be made, but it must. At a time when national politics was dominated by a class of landed proprietors willing to collaborate with the British, their interventions were pivotal in moulding a more progressive generation of scholars.

Jayawardena stood out in that generation, even if her discipline was political science, not history. Not that such demarcations ever mattered: though a political scientist by training, she was a historian by conviction. The essays, books, and other interventions she made filled gaps that almost none of her contemporaries could. Eventually, 19th and 20th century Sri Lankan society, the material and social history of British Ceylon, became her specialisation. At the National Archives, which she visited regularly, she discovered a rich storehouse of material from this period – including colonial despatches – which had been used by other scholars, but gained a new lease of life through her writings.

What made these interventions so unique? At a time when Sri Lankan history tended to be seen through the prism of kings, rulers, and prime ministers, she preferred to write on the marginalised underclass: workers, peasants, and political radicals. Among the many figures she re-evaluated here was Anagarika Dharmapala: she devoted a considerable portion of her work on the labour movement in Sri Lanka to him. By this point, Dharmapala, like that other parvenu of 20th century Sri Lanka, A. E. Goonesinha, tended to be lionised or demonised by the establishment, depending on the ideological sympathies of the writer or historian. Jayawardena rescued him from these polarities.

The significance of Jayawardena’s essays becomes clear here when you look at what history writing had become by then and would deteriorate into later. A case in point would be what I see as her magnum opus, Nobodies to Somebodies.

“Why did she have to dig so much? What did it matter that we were arrack renters or plantation owners? Couldn’t she have left us in peace?”

Simply put, that kind of historical writing was not done, or permitted, when the likes of Jayawardena, Gunasinghe, and Michael Roberts began their careers. A work like Nobodies to Somebodies resonates today in a way that, for instance, K. M. de Silva’s biographies of D. S. Senanayake and J. R. Jayewardene – the latter deconstructed admirably by Rajiva Wijesinha in his recent study of Jayewardene – do not, because there’s no attempt at depicting their subjects as icons and mannequins. This is not to demean those other books, but merely to suggest that her approach was radically different.

Since then the situation has deteriorated considerably. One is tempted to rail against the Sri Lankan State here. Successive regimes have attacked academic freedom, and they need to be censured. Such onslaughts, however, have been more than matched by a diminution in academic standards throughout the country.

Today both academia and think-tank spaces have become bureaucratised, compartmentalised, and commodified, a reflection of what they used to be. It is easy and legitimate to criticise the government’s complicity in all this. But there are other reasons for the decline as well.

At the CHDM screening, much was made about the importance of producing knowledge, and the contribution of the non-governmental or development sector to this. But I think it’s only fair to say that, deplorable as the government’s response to the development sector has been over the last 50 years, the development sector itself has failed to recover from the shocks of the 1980s and 1990s. It continues its downward trajectory.

Jayawardena’s interventions were unique and progressive because they dared to question mainstream narratives. Today, both the government and the highly stratified NGO space of Colombo have been tamed to regurgitate those narratives.

This is not to say that we cannot conjure a Kumari Jayawardena, but that – to rehash an earlier point – we cannot judge her contributions in isolation from the period she hailed from. Like Camelot, it is a period we can only dream of returning to: another time, another world.

Uditha Devapriya is a regular commentator on history, art and culture, politics, and foreign policy who can be reached at . Together with Uthpala Wijesuriya, he heads U & U, an informal art and culture research collective.