Sat Mag

A star that shines against mist-clad Sri Pada

By Uditha Devapriya

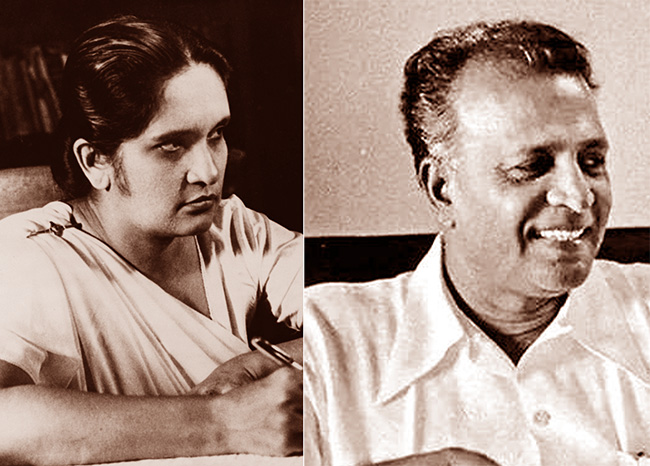

Punya Heedeniya turned 82 on July 31. She was 25 when I first saw her many, many years ago on television, and 78 when I first met her in Colombo, one dull December evening. She had returned home with her husband and had run through a whole set of interviews with other newspapers, periodicals, and magazines.

That year, 2016, had been special to her: together with Nanda Malini, Sumitra Peries, Lester James Peries, and Amaradeva (who had passed away the previous month), the Sarasaviya Awards, held after eight years, had decided to bestow the “Abhimani” Lifetime Achievement accolade on her. Naturally, everyone in town wanted an interview. I was destined to be the last: she and her husband had planned to leave the following day.

From the 12th floor of Queen’s Court Apartment in Colpetty, you can see Sri Pada when the clouds and the dust settle. “I never fail to observe it,” Punya told me before we began the interview. “It reminds me of home,” she added. It also brings back memories of her debut. Deiyange Rate, directed by L. S. Ramachandran, produced by S. D. S. Somaratne, and based on a W. A. Silva novel, was made before she turned 20. “We ascended Maha Giri Dambe and shot Edward Senaratne lip syncing to H. R Jothipala. Try as he might, though, he couldn’t mouth his lines. So we ended up climbing 16 times.”

She looked to the horizon, beyond the windows. “I wake up every morning to the silhouette of the Peak.” She paused. “To me, it has always been a good omen.”

At Mirigama Madya Maha Vidyalaya, Punya had been an astute student and a voracious reader. She had also been a modest dancer. Apparently W. A. Silva had been a favourite: she read Deiyange Rate in middle school. This helped when a cousin of hers who knew S. D. S. Somaratne suggested her name after the erstwhile Senator and film producer asked him if he knew anyone who could play the role of Catherine, the female protagonist of the story. Punya’s father, however, needed some convincing; once her cousin and Somaratne got his permission, they whisked her away. L. S. Ramachandran had his office in Hulftsdorp, and the aspiring actress was asked to recite a section from the book. In her own words, “I not only recited it, I also performed it in front of them.” She was in.

Mirigama lies 60 kilometres away from Colombo. Situated in the Gampaha district; it is well known as the hometown of the first Prime Minister of Sri Lanka, connecting, on one side, to Kandy and, the other, to Kurunegala.

Punya came from a petty bourgeois family here. She lived “in two worlds”, as she put to me in my interview: that of the village and that of her school, where, in contrast to her Sinhala Buddhist upbringing, “I received an English education.” There she came under the powerful influence of her teachers, including the great Panibharatha.

Punya came from a petty bourgeois family here. She lived “in two worlds”, as she put to me in my interview: that of the village and that of her school, where, in contrast to her Sinhala Buddhist upbringing, “I received an English education.” There she came under the powerful influence of her teachers, including the great Panibharatha.

“It was Panibharatha who got me into the performing arts,” she reflected, as her husband brought us tea and biscuits. She underscored her childhood lack of interest in dancing, singing, and acting with the fact that she didn’t take part in a single play at school. She wasn’t quite 17, almost out of school in fact, when Panibharatha called her to act in two dance sequences in Ashoka somewhere in 1953. “That was my initiation into films, though all what those two scenes amounted to was a set of traditional ballet items.”

This first encounter had intrigued her. Coming as she did from a staunch, traditional Sinhala Buddhist family, “I found it strange to reveal myself in front of an impersonal camera.” Her later encounters with the Minerva Players, including Rukmani Devi and the Jayamanne brothers, alienated her even more. “I realised how full of artifice the acting in their films was. After seeing them, I realised that to prosper as an actor, you had to break out of that mould. You had to become yourself.”

So how could a Sinhala Buddhist rural middle class girl from a suburb several miles from the capital city become herself? By selecting and getting roles that reflected her upbringing, of course. There’s a reason, after all, why Punya became the quintessential Sinhala woman on film, something not even Malini Fonseka equalled. Considering that such an achievement has been the result of a mere fraction of the roles Malini got, Punya’s importance – not only as an formidable actress, but also as an unmistakable symbol of how socio-cultural dynamics find their expression in a nation’s art forms – cannot be understated.

In the middle of a casual conversation with Lester James and Sumitra Peries years ago, I suddenly asked them to describe the milieu Punya hailed from. “I would say conservative, right of centre,” Lester conjectured. Sumitra was more specific. “They would have been the sort who voted for the UNP because of their landed interests and voted for the SLFP in 1956 because of their Buddhist roots.”

Scholars have interpreted the transformation of the underlying ethos of the national cinema in terms of the electoral change of 1956. In this scheme of things, there was less a transition than a paradigm shift in values, from a Colombo centric elite to a rural underclass. Thus Lester Peries’s Rekava is described as a symbol of the cataclysmic shift from the UNP to the SLFP, forgetting that the shift had been preceded by a change in the dominant ideology of the Sinhala cinema. This is true even of the actors who emerged at that juncture, of whom Punya no doubt represented a cultural high point.

A more comprehensive and thorough study of these trends can be found in Garret Field’s book, Modernizing Composition (University of California Press, 2017). By the end of the 19th century, Field contends, the Buddhist cultural revival had benefitted from the rise of print capitalism and, with it, the growth of an urban lower middle class and working class.

Together with the peasantry and the rural petty bourgeoisie, whose ideology undoubtedly influenced them, they “supported movements of religious revival and social protest.” In fact the line between their working class and ethno-nationalist aspirations blurred with the years, culminating in their participation in the 1915 riots that, as the likes of Kumari Jayawardena (who I’ve quoted above) have noted, had greater working class involvement than most commentators see it today.

The urban lower middle class and the urban working class found a ready outlet for their aspirations in the plays of travelling Parsi troupes. Field does not note the irony of an urban Sinhala middle class intelligentsia following up their support for Colonel Olcott’s Buddhist Theosophical Society and Anagarika Dharmapala’s revivalism with an enthusiastic reception of a dramatic form originating in a completely non Buddhist community, but the irony, if at all, can be explained by the fact that the organisers of these productions indigenised their themes to address issues considered relevant and pressing by that intelligentsia: in Field’s summing up, “edification, temperance, and education.” John de Silva’s act of indigenising them even more must be seen in this light. In converting a nationalist audience to his plays, he was, not surprisingly, being as much a capitalist as a “nationalist.”

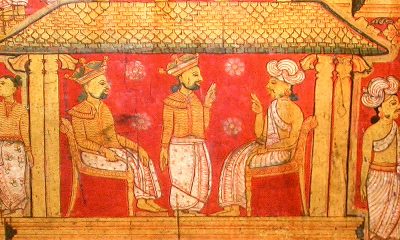

The Parsees influenced the local urban theatre; it did the same with the local urban cinema. Ratnabivushana and Dissanayake, in regrettably the only study of its kind, conjecture that by the time of Kadawunu Poronduwa the “local film industry”, premature though it may have been, had come to cater to a largely urban Sinhala milieu. With its blend of Indian music and Sinhala poetry, its idealisation of Sinhala Buddhist “Arya” values through a mishmash of ragadhari and folk music, its appeal was unmistakeably profound.

Kumari Jayawardena writes of an instance where, during a performance of John de Silva’s play Sri Wickrama, a drunken sailor got up onstage and attempted to stop the actors playing the royal guards from leading Ahelepola’s family to their death at the hands of the last Kandyan king. You can see history being rewritten if not skewed in favour of a totalising “Sinhala” narrative right there, in the play’s denigration of that king as an evil, lustful murderer, though this reading is ironically pro British as Gananath Obeyesekere has shown. In any case, that peculiar worldview shaped the local cinema as well.

Urban lower middle class and working class society prefers colour, spectacle, the clash of cymbal and drum, and the valorisation of traditional values, and this spills over to more conservative sections of the rural community as time goes by. Unabashedly full of sound and fury, of legend and myth, the Minerva Players films therefore came to appeal to a considerable section of this population.

And yet, they were not enough. A more indigenous alternative had to spring up. The pioneers here were Sirisena Wimalaweera and Jayavilal Wilegoda, the one a director and the other an uncompromising critic. The anglicised upper class, meanwhile, sought refuge in the Western cinema; in 1945 they formed the Colombo Film Society, which as Lester Peries wittily observed in 1957 catered to “the culture snobs of Colombo 7.”

With its inadvertent mimicking of the Indian melodrama, the Sinhala cinema soon faced a crisis: by 1950, foreign films were being watched in greater numbers than local ones. At the time the music industry had moved from its Parsi roots: in the songs of Ananda Samarakoon and Sunil Shantha – both, incidentally, hailing from non-Buddhist backgrounds – the melody had become conspicuously more Sinhala. The Sinhala film, however, had not.

In reacting against the intrusion of the Indian melodrama, directors and scriptwriters decided to fight fire with fire. They began imitating the more openly and popular Hindi films. This had been done before, but as Ratnabivushana and Dissanayake note, “now the decision was to do [it] more brazenly.”

At this crucial juncture, directors of popular films returned to popular Sinhala literature. In W. A. Silva they found a saving grace. Even the Minerva Players realised this: the first adaptation of a Sinhala novel was not only based on one written by Silva, but also directed by B. A. W. Jayamanne: Kele Handa. Full of bawdy humour and physical combat, and set in a world where good and evil were divided into two irreconcilable halves, these new films – of which the apogee has to be Mathalan (1956) – projected a new set of values, though borrowing much from the films of an earlier era.

A new generation of producers soon emerged, among them S. D. S. Somaratne. With them, a new generation of directors: T. Somasekaran, Robin Tampoe, M. Masthan, Shanthi Kumar, Lenin Moraes, and L. S. Ramachandran. With them also, a new generation of actresses: Mallika Pilapitiya, Kanthi Gunathunga, and Punya Heendeniya. In the great twilight between Rukmani Devi and Malini Fonseka, Punya hence soon stood out from the rest.

Here I return to Punya, gazing at me, smiling openly as she and her husband remember their time in Africa and London and later in a different Sri Lanka, where they returned so that she could take up her signature role, as Nanda, in the sequel to Gamperaliya, Kaliyugaya. If you remember correctly, one of the more curious anachronisms in these two stories is that none of the women from the old order – including Nanda and her sister Anula – speaks English. When they have to do so, they rely on an interlocutor, like Nanda’s brother Tissa.

Vinod Moonesinghe tells me that this isn’t really historically accurate: the women of the old order,

when they joined the new, did try to learn English, just as their ancestors tried to learn and speak

Portuguese. That does not concern me though. What concerns me is the sociology behind it; the same sociology which explains not just the milieu of women like Nanda, but also the milieu of the

woman who played Nanda.

I left Punya Heendeniya there on the 12th floor, looking at Sri Pada and making plans for her departure the next day. I haven’t seen her since. I should, and hopefully, I will.

The writer can be reached at udakdev1@gmail.com

Sat Mag

October 13 at the Women’s T20 World Cup: Injury concerns for Australia ahead of blockbuster game vs India

Australia vs India

Sharjah, 6pm local time

Australia have major injury concerns heading into the crucial clash. Just four balls into the match against Pakistan, Tayla Vlaeminck was out with a right shoulder dislocation. To make things worse, captain Alyssa Healy suffered an acute right foot injury while batting on 37 as she hobbled off the field with Australia needing 14 runs to win. Both players went for scans on Saturday.

India captain Harmanpreet Kaur who had hurt her neck in the match against Pakistan, turned up with a pain-relief patch on the right side of her neck during the Sri Lanka match. She also didn’t take the field during the chase. Fast bowler Pooja Vastrakar bowled full-tilt before the Sri Lanka game but didn’t play.

India will want a big win against Australia. If they win by more than 61 runs, they will move ahead of Australia, thereby automatically qualifying for the semi-final. In a case where India win by fewer than 60 runs, they will hope New Zealand win by a very small margin against Pakistan on Monday. For instance, if India make 150 against Australia and win by exactly 10 runs, New Zealand need to beat Pakistan by 28 runs defending 150 to go ahead of India’s NRR. If India lose to Australia by more than 17 runs while chasing a target of 151, then New Zealand’s NRR will be ahead of India, even if Pakistan beat New Zealand by just 1 run while defending 150.

Overall, India have won just eight out of 34 T20Is they’ve played against Australia. Two of those wins came in the group-stage games of previous T20 World Cups, in 2018 and 2020.

Australia squad:

Alyssa Healy (capt & wk), Darcie Brown, Ashleigh Gardner, Kim Garth, Grace Harris, Alana King, Phoebe Litchfield, Tahlia McGrath, Sophie Molineux, Beth Mooney, Ellyse Perry, Megan Schutt, Annabel Sutherland, Tayla Vlaeminck, Georgia Wareham

India squad:

Harmanpreet Kaur (capt), Smriti Mandhana (vice-capt), Yastika Bhatia (wk), Shafali Verma, Deepti Sharma, Jemimah Rodrigues, Richa Ghosh (wk), Pooja Vastrakar, Arundhati Reddy, Renuka Singh, D Hemalatha, Asha Sobhana, Radha Yadav, Shreyanka Patil, S Sajana

Tournament form guide:

Australia have three wins in three matches and are coming into this contest having comprehensively beaten Pakistan. With that win, they also all but sealed a semi-final spot thanks to their net run rate of 2.786. India have two wins in three games. In their previous match, they posted the highest total of the tournament so far – 172 for 3 and in return bundled Sri Lanka out for 90 to post their biggest win by runs at the T20 World Cup.

Players to watch:

Two of their best batters finding their form bodes well for India heading into the big game. Harmanpreet and Mandhana’s collaborative effort against Pakistan boosted India’s NRR with the semi-final race heating up. Mandhana, after a cautious start to her innings, changed gears and took on Sri Lanka’s spinners to make 50 off 38 balls. Harmanpreet, continuing from where she’d left against Pakistan, played a classic, hitting eight fours and a six on her way to a 27-ball 52. It was just what India needed to reinvigorate their T20 World Cup campaign.

[Cricinfo]

Sat Mag

Living building challenge

By Eng. Thushara Dissanayake

The primitive man lived in caves to get shelter from the weather. With the progression of human civilization, people wanted more sophisticated buildings to fulfill many other needs and were able to accomplish them with the help of advanced technologies. Security, privacy, storage, and living with comfort are the common requirements people expect today from residential buildings. In addition, different types of buildings are designed and constructed as public, commercial, industrial, and even cultural or religious with many advanced features and facilities to suit different requirements.

We are facing many environmental challenges today. The most severe of those is global warming which results in many negative impacts, like floods, droughts, strong winds, heatwaves, and sea level rise due to the melting of glaciers. We are experiencing many of those in addition to some local issues like environmental pollution. According to estimates buildings account for nearly 40% of all greenhouse gas emissions. In light of these issues, we have two options; we change or wait till the change comes to us. Waiting till the change come to us means that we do not care about our environment and as a result we would have to face disastrous consequences. Then how can we change in terms of building construction?

Before the green concept and green building practices come into play majority of buildings in Sri Lanka were designed and constructed just focusing on their intended functional requirements. Hence, it was much likely that the whole process of design, construction, and operation could have gone against nature unless done following specific regulations that would minimize negative environmental effects.

We can no longer proceed with the way we design our buildings which consumes a huge amount of material and non-renewable energy. We are very concerned about the food we eat and the things we consume. But we are not worrying about what is a building made of. If buildings are to become a part of our environment we have to design, build and operate them based on the same principles that govern the natural world. Eventually, it is not about the existence of the buildings, it is about us. In other words, our buildings should be a part of our natural environment.

The living building challenge is a remarkable design philosophy developed by American architect Jason F. McLennan the founder of the International Living Future Institute (ILFI). The International Living Future Institute is an environmental NGO committed to catalyzing the transformation toward communities that are socially just, culturally rich, and ecologically restorative. Accordingly, a living building must meet seven strict requirements, rather certifications, which are called the seven “petals” of the living building. They are Place, Water, Energy, Equity, Materials, Beauty, and Health & Happiness. Presently there are about 390 projects around the world that are being implemented according to Living Building certification guidelines. Let us see what these seven petals are.

Place

This is mainly about using the location wisely. Ample space is allocated to grow food. The location is easily accessible for pedestrians and those who use bicycles. The building maintains a healthy relationship with nature. The objective is to move away from commercial developments to eco-friendly developments where people can interact with nature.

Water

It is recommended to use potable water wisely, and manage stormwater and drainage. Hence, all the water needs are captured from precipitation or within the same system, where grey and black waters are purified on-site and reused.

Energy

Living buildings are energy efficient and produce renewable energy. They operate in a pollution-free manner without carbon emissions. They rely only on solar energy or any other renewable energy and hence there will be no energy bills.

Equity

What if a building can adhere to social values like equity and inclusiveness benefiting a wider community? Yes indeed, living buildings serve that end as well. The property blocks neither fresh air nor sunlight to other adjacent properties. In addition, the building does not block any natural water path and emits nothing harmful to its neighbors. On the human scale, the equity petal recognizes that developments should foster an equitable community regardless of an individual’s background, age, class, race, gender, or sexual orientation.

Materials

Materials are used without harming their sustainability. They are non-toxic and waste is minimized during the construction process. The hazardous materials traditionally used in building components like asbestos, PVC, cadmium, lead, mercury, and many others are avoided. In general, the living buildings will not consist of materials that could negatively impact human or ecological health.

Beauty

Our physical environments are not that friendly to us and sometimes seem to be inhumane. In contrast, a living building is biophilic (inspired by nature) with aesthetical designs that beautify the surrounding neighborhood. The beauty of nature is used to motivate people to protect and care for our environment by connecting people and nature.

Health & Happiness

The building has a good indoor and outdoor connection. It promotes the occupants’ physical and psychological health while causing no harm to the health issues of its neighbors. It consists of inviting stairways and is equipped with operable windows that provide ample natural daylight and ventilation. Indoor air quality is maintained at a satisfactory level and kitchen, bathrooms, and janitorial areas are provided with exhaust systems. Further, mechanisms placed in entrances prevent any materials carried inside from shoes.

The Bullitt Center building

Bullitt Center located in the middle of Seattle in the USA, is renowned as the world’s greenest commercial building and the first office building to earn Living Building certification. It is a six-story building with an area of 50,000 square feet. The area existed as a forest before the city was built. Hence, the Bullitt Center building has been designed to mimic the functions of a forest.

The energy needs of the building are purely powered by the solar system on the rooftop. Even though Seattle is relatively a cloudy city the Bullitt Center has been able to produce more energy than it needed becoming one of the “net positive” solar energy buildings in the world. The important point is that if a building is energy efficient only the area of the roof is sufficient to generate solar power to meet its energy requirement.

It is equipped with an automated window system that is able to control the inside temperature according to external weather conditions. In addition, a geothermal heat exchange system is available as the source of heating and cooling for the building. Heat pumps convey heat stored in the ground to warm the building in the winter. Similarly, heat from the building is conveyed into the ground during the summer.

The potable water needs of the building are achieved by treating rainwater. The grey water produced from the building is treated and re-used to feed rooftop gardens on the third floor. The black water doesn’t need a sewer connection as it is treated to a desirable level and sent to a nearby wetland while human biosolid is diverted to a composting system. Further, nearly two third of the rainwater collected from the roof is fed into the groundwater and the process resembles the hydrologic function of a forest.

It is encouraging to see that most of our large-scale buildings are designed and constructed incorporating green building concepts, which are mainly based on environmental sustainability. The living building challenge can be considered an extension of the green building concept. Amanda Sturgeon, the former CEO of the ILFI, has this to say in this regard. “Before we start a project trying to cram in every sustainable solution, why not take a step outside and just ask the question; what would nature do”?

Sat Mag

Something of a revolution: The LSSP’s “Great Betrayal” in retrospect

By Uditha Devapriya

On June 7, 1964, the Central Committee of the Lanka Sama Samaja Party convened a special conference at which three resolutions were presented. The first, moved by N. M. Perera, called for a coalition with the SLFP, inclusive of any ministerial portfolios. The second, led by the likes of Colvin R. de Silva, Leslie Goonewardena, and Bernard Soysa, advocated a line of critical support for the SLFP, but without entering into a coalition. The third, supported by the likes of Edmund Samarakkody and Bala Tampoe, rejected any form of compromise with the SLFP and argued that the LSSP should remain an independent party.

The conference was held a year after three parties – the LSSP, the Communist Party, and Philip Gunawardena’s Mahajana Eksath Peramuna – had founded a United Left Front. The ULF’s formation came in the wake of a spate of strikes against the Sirimavo Bandaranaike government. The previous year, the Ceylon Transport Board had waged a 17-day strike, and the harbour unions a 60-day strike. In 1963 a group of working-class organisations, calling itself the Joint Committee of Trade Unions, began mobilising itself. It soon came up with a common programme, and presented a list of 21 radical demands.

In response to these demands, Bandaranaike eventually supported a coalition arrangement with the left. In this she was opposed, not merely by the right-wing of her party, led by C. P. de Silva, but also those in left parties opposed to such an agreement, including Bala Tampoe and Edmund Samarakkody. Until then these parties had never seen the SLFP as a force to reckon with: Leslie Goonewardena, for instance, had characterised it as “a Centre Party with a programme of moderate reforms”, while Colvin R. de Silva had described it as “capitalist”, no different to the UNP and by default as bourgeois as the latter.

The LSSP’s decision to partner with the government had a great deal to do with its changing opinions about the SLFP. This, in turn, was influenced by developments abroad. In 1944, the Fourth International, which the LSSP had affiliated itself with in 1940 following its split with the Stalinist faction, appointed Michel Pablo as its International Secretary. After the end of the war, Pablo oversaw a shift in the Fourth International’s attitude to the Soviet states in Eastern Europe. More controversially, he began advocating a strategy of cooperation with mass organisations, regardless of their working-class or radical credentials.

Pablo argued that from an objective perspective, tensions between the US and the Soviet Union would lead to a “global civil war”, in which the Soviet Union would serve as a midwife for world socialist revolution. In such a situation the Fourth International would have to take sides. Here he advocated a strategy of entryism vis-à-vis Stalinist parties: since the conflict was between Stalinist and capitalist regimes, he reasoned, it made sense to see the former as allies. Such a strategy would, in his opinion, lead to “integration” into a mass movement, enabling the latter to rise to the level of a revolutionary movement.

Though controversial, Pablo’s line is best seen in the context of his times. The resurgence of capitalism after the war, and the boom in commodity prices, had a profound impact on the course of socialist politics in the Third World. The stunted nature of the bourgeoisie in these societies had forced left parties to look for alternatives. For a while, Trotsky had been their guide: in colonial and semi-colonial societies, he had noted, only the working class could be expected to see through a revolution. This entailed the establishment of workers’ states, but only those arising from a proletarian revolution: a proposition which, logically, excluded any compromise with non-radical “alternatives” to the bourgeoisie.

To be sure, the Pabloites did not waver in their support for workers’ states. However, they questioned whether such states could arise only from a proletarian revolution. For obvious reasons, their reasoning had great relevance for Trotskyite parties in the Third World. The LSSP’s response to them showed this well: while rejecting any alliance with Stalinist parties, the LSSP sympathised with the Pabloites’ advocacy of entryism, which involved a strategic orientation towards “reformist politics.” For the world’s oldest Trotskyite party, then going through a series of convulsions, ruptures, and splits, the prospect of entering the reformist path without abandoning its radical roots proved to be welcoming.

Writing in the left-wing journal Community in 1962, Hector Abhayavardhana noted some of the key concerns that the party had tried to resolve upon its formation. Abhayavardhana traced the LSSP’s origins to three developments: international communism, the freedom struggle in India, and local imperatives. The latter had dictated the LSSP’s manifesto in 1936, which included such demands as free school books and the use of Sinhala and Tamil in the law courts. Abhayavardhana suggested, correctly, that once these imperatives changed, so would the party’s focus, though within a revolutionary framework. These changes would be contingent on two important factors: the establishment of universal franchise in 1931, and the transfer of power to the local bourgeoisie in 1948.

Paradoxical as it may seem, the LSSP had entered the arena of radical politics through the ballot box. While leading the struggle outside parliament, it waged a struggle inside it also. This dual strategy collapsed when the colonial government proscribed the party and the D. S. Senanayake government disenfranchised plantation Tamils. Suffering two defeats in a row, the LSSP was forced to think of alternatives. That meant rethinking categories such as class, and grounding them in the concrete realities of the country.

This was more or less informed by the irrelevance of classical and orthodox Marxian analysis to the situation in Sri Lanka, specifically to its rural society: with a “vast amorphous mass of village inhabitants”, Abhayavardhana observed, there was no real basis in the country for a struggle “between rich owners and the rural poor.” To complicate matters further, reforms like the franchise and free education, which had aimed at the emancipation of the poor, had in fact driven them away from “revolutionary inclinations.” The result was the flowering of a powerful rural middle-class, which the LSSP, to its discomfort, found it could not mobilise as much as it had the urban workers and plantation Tamils.

Where else could the left turn to? The obvious answer was the rural peasantry. But the rural peasantry was in itself incapable of revolution, as Hector Abhayavardhana has noted only too clearly. While opposing the UNP’s Westernised veneer, it did not necessarily oppose the UNP’s overtures to Sinhalese nationalism. As historians like K. M. de Silva have observed, the leaders of the UNP did not see their Westernised ethos as an impediment to obtaining support from the rural masses. That, in part at least, was what motivated the Senanayake government to deprive Indian estate workers of their most fundamental rights, despite the existence of pro-minority legal safeguards in the Soulbury Constitution.

To say this is not to overlook the unique character of the Sri Lankan rural peasantry and petty bourgeoisie. Orthodox Marxists, not unjustifiably, characterise the latter as socially and politically conservative, tilting more often than not to the right. In Sri Lanka, this has frequently been the case: they voted for the UNP in 1948 and 1952, and voted en masse against the SLFP in 1977. Yet during these years they also tilted to the left, if not the centre-left: it was the petty bourgeoisie, after all, which rallied around the SLFP, and supported its more important reforms, such as the nationalisation of transport services.

One must, of course, be wary of pasting the radical tag on these measures and the classes that ostensibly stood for them. But if the Trotskyite critique of the bourgeoisie – that they were incapable of reform, even less revolution – holds valid, which it does, then the left in the former colonies of the Third World had no alternative but to look elsewhere and to be, as Abhayavardhana noted, “practical men” with regard to electoral politics. The limits within which they had to work in Sri Lanka meant that, in the face of changing dynamics, especially among the country’s middle-classes, they had to change their tactics too.

Meanwhile, in 1953, the Trotskyite critique of Pabloism culminated with the publication of an Open Letter by James Cannon, of the US Socialist Workers’ Party. Cannon criticised the Pabloite line, arguing that it advocated a policy of “complete submission.” The publication of the letter led to the withdrawal of the International Committee of the Fourth International from the International Secretariat. The latter, led by Pablo, continued to influence socialist parties in the Third World, advocating temporary alliances with petty bourgeois and centrist formations in the guise of opposing capitalist governments.

For the LSSP, this was a much-needed opening. Even as late as 1954, three years after S. W. R. D. Bandaranaike formed the SLFP, the LSSP continued to characterise the latter as the alternative bourgeois party in Ceylon. Yet this did not deter it from striking up no contest pacts with Bandaranaike at the 1956 election, a strategy that went back to November 1951, when the party requested the SLFP to hold a discussion about the possibility of eliminating contests in the following year’s elections. Though it extended critical support to the MEP government in 1956, the LSSP opposed the latter once it enacted emergency measures in 1957, mobilising trade union action for a period of three years.

At the 1960 election the LSSP contested separately, with the slogan “N. M. for P.M.” Though Sinhala nationalism no longer held sway as it had in 1956, the LSSP found itself reduced to a paltry 10 seats. It was against this backdrop that it began rethinking its strategy vis-à-vis the ruling party. At the throne speech in April 1960, Perera openly declared that his party would not stabilise the SLFP. But a month later, in May, he called a special conference, where he moved a resolution for a coalition with the party. As T. Perera has noted in his biography of Edmund Samarakkody, the response to the resolution unearthed two tendencies within the oppositionist camp: the “hardliners” who opposed any compromise with the SLFP, including Samarakkody, and the “waverers”, including Leslie Goonewardena.

These tendencies expressed themselves more clearly at the 1964 conference. While the first resolution by Perera called for a complete coalition, inclusive of Ministries, and the second rejected a coalition while extending critical support, the third rejected both tactics. The outcome of the conference showed which way these tendencies had blown since they first manifested four years earlier: Perera’s resolution obtained more than 500 votes, the second 75 votes, the third 25. What the anti-coalitionists saw as the “Great Betrayal” of the LSSP began here: in a volte-face from its earlier position, the LSSP now held the SLFP as a party of a radical petty bourgeoisie, capable of reform.

History has not been kind to the LSSP’s decision. From 1970 to 1977, a period of less than a decade, these strategies enabled it, as well as the Communist Party, to obtain a number of Ministries, as partners of a petty bourgeois establishment. This arrangement collapsed the moment the SLFP turned to the right and expelled the left from its ranks in 1975, in a move which culminated with the SLFP’s own dissolution two years later.

As the likes of Samarakkody and Meryl Fernando have noted, the SLFP needed the LSSP and Communist Party, rather than the other way around. In the face of mass protests and strikes in 1962, the SLFP had been on the verge of complete collapse. The anti-coalitionists in the LSSP, having established themselves as the LSSP-R, contended later on that the LSSP could have made use of this opportunity to topple the government.

Whether or not the LSSP could have done this, one can’t really tell. However, regardless of what the LSSP chose to do, it must be pointed out that these decades saw the formation of several regimes in the Third World which posed as alternatives to Stalinism and capitalism. Moreover, the LSSP’s decision enabled it to see through certain important reforms. These included Workers’ Councils. Critics of these measures can point out, as they have, that they could have been implemented by any other regime. But they weren’t. And therein lies the rub: for all its failings, and for a brief period at least, the LSSP-CP-SLFP coalition which won elections in 1970 saw through something of a revolution in the country.

The writer is an international relations analyst, researcher, and columnist based in Sri Lanka who can be reached at udakdev1@gmail.com

-

Editorial7 days ago

Editorial7 days agoIllusory rule of law

-

Features7 days ago

Features7 days agoDaydreams on a winter’s day

-

Features7 days ago

Features7 days agoSurprise move of both the Minister and myself from Agriculture to Education

-

Features6 days ago

Features6 days agoExtended mind thesis:A Buddhist perspective

-

Features7 days ago

Features7 days agoThe Story of Furniture in Sri Lanka

-

Opinion5 days ago

Opinion5 days agoAmerican rulers’ hatred for Venezuela and its leaders

-

Features7 days ago

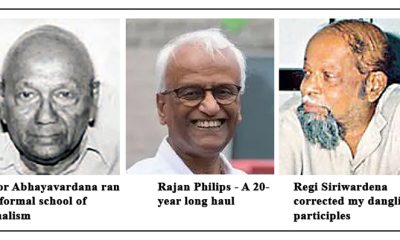

Features7 days agoWriting a Sunday Column for the Island in the Sun

-

Business3 days ago

Business3 days agoCORALL Conservation Trust Fund – a historic first for SL