Opinion

A fable: Misappropriation Bill presented in Parliament of Sovereign Kleptocratic Republic of Chauristan

by Usvatte-aratchi

No, you will not find it among the five ‘Stan Countries’ in the massive spread of Eurasia. Go further south and further east until you meet a sizeable island, not quite utima thule. Ask any forlorn-looking young man in that land where cones on stupa nearly scrape the underbelly of heavens, ‘In this seemingly pleasant land, what is the profession where a person with no inherited wealth, no education, and no professional skills can amass vast wealth in less than five years?’ The young man turned to him as if the stranger were a gross ignoramus and answered, ‘Why silly, politics? This is where asinus rex est.’ ‘Did you say, a land where the donkey is king’? How so?’ asks the visitor. ‘By misappropriating public funds’, gravely replied the young man, ‘to continue which, there is today a Misappropriation Bill presented before the House. It is mainly for misappropriating public funds, first by misallocation’. ‘That is probably why those rich thieves thrive luxuriantly outside a jail. In other countries, such men and women are housed at state expense in jails and at somewhat less comfort than princely. The state owes at least that little to those geniuses, who brought such immense ill fame to this land.’

A few days ago, the Chaurisri, the president of the Chaurigrha (that is the name of the Parliament like the Knesset in Israel or the Duma in Japan) announced the first reading of the said Misappropriation Bill. Since 2005, the annual Misappropriation Bill has been the principal instrument used to plunder the revenue of the state. Revenue (misnamed government income) of the state comprises tax revenue, government income and proceeds from loans raised by the government, each year. The misappropriation has been so gross, systematic, persistent and thorough that the kleptocratic republic won infamy in international fora including lending institutions, as a dark hole that sank money that should have benefited the common people of that country. As was inevitable, the Treasury was empty and the people were left with only foul air to breathe. Yet, Chauripurohit (Minister of Finance), who is also Chauripathi, announced in Chaurigrha that corruption in that land was but ‘a fable’. If the purohit spoke the truth, which he betimes does, then the truth in Chauristan is incredibly fabulous (Fable and fabulous come from the same Latin word ‘fabula.) At the bottom of that dark hole sat a spreading family of fat cats whose skills were confined to deception and corruption. They could not catch so much as a mouse who dared to pilfer some of the Swiss cheese they had imported to fatten the cats. One of the lenders to Chauristan was so concerned that its funds should not be misappropriated, that it appointed its own accountants and auditors when lending to the government of Chauristan. Knowledgeable taxpayers avoided and evaded tax payments because they knew that their taxes only would fatten the family of cats who would litter more. Other taxpayers and potential taxpayers flew out in flocks. The cost of those preventive measures became a part of the loan that the taxpayers of Chauristan would eventually repay.

Three parties misappropriated funds for their benefit. First the members of the Executive Branch of the government from the highest to the lowest. Those sums were fittingly very high. It is commonly averred that they siphoned 20 percent of any loan proceeds and of the price of large contracts. The contractors themselves plundered public funds by using sub-standard material, cheating on measurements and abandoning projects fully paid up but only partly done. There were three important consequences. First, the highest in the executive branch who decided on which projects or which version of a project would be selected, always and inevitably opted for the highest-priced project on offer. The reasoning was quite simple: 20 percent of $20 million raised a bribe of $4 million and 20 percent of 100 million gave $20 million and some loans exceeded a few billion US dollars. There were more than a few who shared each loot. Second, all large-scale projects were financed with loans from overseas with some marginal contribution from tax revenue. The Family avoided accepting offers of projects from countries and companies that would not collude with the Family to offer the cut that the Family wanted and further, deposit the bribe in banks outside Chauristan. So solicitous were they for the good name of Chauristan that they kept their gold securely in a locked Pandora’s Box. The most egregiously corrupt instance was when the government of Chauristan turned down a Light Rail Project offered almost free by a friendly government. Thirdly, as projects which had been accepted became either completely or partially unproductive, the burden of repayment fell on taxpayers, whose income had not increased at all. If you built a house and nobody took it on rent, you would pay the loan to the bank from your monthly salary and that at the cost of milk for your baby. The responsibility is yours for having put up that house in a devil’s cemetery. In reaction, when the burden of taxation became too heavy to bear, some refused to earn beyond a certain upper limit, some packed their bags and looked for refuge overseas and the very poor withered on the vine like grapes in winter in northern Italy. Loans were used to build 40 foot-wide roads on which crocodiles slumbered in the sun and buffaloes gambolled idly, airports, where hangars stored rice and sheltered no airplanes, ports where ships did not call, theatres where ghosts (not Ibsen’s) found permanent residence and where tall columns kept watchful guard over teals nesting in the bushes near the Beira. They did not produce an income adequate to service the loans and people in other sectors were starved to pay off loans while the cats and (Kaputas) crows grew visibly fatter. When those other sectors were destroyed wilfully by one member of the Family and by circumstances well beyond the control of the Family, the economy fell with a thud and woeful consequences fell upon the public. Yet, the cats grew fatter. Purposely and wilfully, one member of the Family denied large sums of tax revenue to the government and diverted that flow to Family friends who also had helped pay for their election to office and also to evade justice. The problem was further complicated as some of these loans were from overseas and had to be serviced with foreign currency. The value of the domestic currency in both foreign exchange and domestic markets tanked. Price inflation soared higher and faster than a kite in August on Galle Face Green.

The second group that misappropriated funds were rich traders who had power and influence over the said Family. Those had gained from the losses to the government treasury and at the same time to the public. The current Misappropriation Bill provides several honeypots that the kleptocrats must already savour. Government enterprises making good profits are up for sale to the private sector, even to the very private sector enterprises and individuals who had plundered the public purse. The capital that the Fat Cats publicly denied owning will suddenly emerge from where they were hidden, and black money will suddenly whiten and glisten and so will be born the Sri Lanka oligarchs. Wealth now hidden in properties in Australia, Europe, Africa, islands in the Indian Ocean and in the Caribbean will flow into Chauristan. Several miracles will occur simultaneously: black money will glisten and whiten blindingly; plunderers in kapati suits will fatten further in Parisian suits and Italian shoes; Sri Lanka’s capital account in the balance of payments will be in the black temporarily. It will be perestroika all over again but in a teacup. Voters need to understand these shenanigans well and elect representatives who will confine plunderers in jail and recover the loot forthwith.

The third group of plunderers was bureaucrats at very high levels. Senior Advisors to presidents, the prime minister and other ministers were notoriously corrupt. Many were caught with their sticky fingers in the kitty but skillful lawyering and unscrupulous politicians installed them back in higher positions and with substantially higher pay. And so merrily did they plunder; the Chauripurohit was right; it was fabulous (fable-like).

The Misappropriation Bill was presented in Chaurigrha as if there was only a macroeconomic problem ailing the economy. All the talk was about primary balances and stability in the economy. There was not a word about the horrors committed by the misallocation of resources. They were fables: my left cleft foot! Everyone breathed the macro-economic vapour and in the ensuing stupor forgot that it was misallocating resources and mismanaging individual projects that summed up to the macro-economic disasters. Thirteen years after the war in Chauristan, defence expenditure keeps on rising at the cost of other sectors including education and health. It is true that defence forces employ large numbers who would otherwise go unemployed and that these young men and women dig trenches and fill them back. Some of them have started making bags for politicians; a few will carry them. But what is the invasion against which the armed forces ever defended Chauristan? Chauristan armed forces cannot withstand for a fortnight even a minor invasion by sea, air and land from any but the smallest powers in its neighbourhood. They failed miserably to prevent a well-planned attack on worshippers at prayer in church on Easter Sunday in 2019, reliable information from other countries notwithstanding. Defend the country: flipping claptrap (Andy Capp might have said). The armed forces in Chauristan arefor the protection of the government against its own people and not for the protection of the state against other states. (One way of confounding the public mind is to confuse the use of the terms state and government so that when people attack a government it is dressed up by government as an attack on the state. Aragalaya attacked the government then in power and not the state of Sri Lanka. They were not traitors to the state of Sri Lanka. In contrast, Eritrea became a separate state after she broke away from Ethiopia. The people who rebelled were traitors to the state of Ethiopia.) Chauripurohit during the budget debate threatened to use armed forces to protect his government from the wrath of the public . That call, in principle, is problematic. After all the armed forces are of the people. But the armed forces are there to maintain public order. Good judgment is of the essence Why not call that outfit the Ministry of Internal Security? Why call a rose by another name?

There is one organ of government that will protect the people from depredation by the government: the judiciary. The judiciary has neither sleuths nor guns nor tanks. The judiciary needs the active support of some important parts of the executive to bring enemies of the people (Ibsen, again) to justice. When the executive fails in its duties and, in fact, colludes with other parts of government to harm the governed, the judiciary is helpless. Allocation is determined by the executive branch of government which can starve the judicial branch of resources. It is the function of the legislature to correct such misallocation.

Allocating massive sums over two decades to projects that overran their originally budgeted resources and construction periods ensured that those projects would bring about waste of capital and minimal rates of economic growth. Of some 5,000 head of cattle imported from New Zealand to Chauristan 90 percent died within a year. Good project management could have eliminated all this waste. In fact, some parts of Chaurigrha brought out these dreadful facts but the mass in that august assembly could not make the connections.

The government of Chauristan is a swamp that drains the flood of unemployed in the economy. Politicians continually widen and deepen that swamp to keep their noses above water. There is roughly one government employee for every 15 persons in the population. There is roughly one teacher per 15 students in schools. More than 20 percent of the labour force in the country work overseas and the recent higher rate of outflow from the country is raising the stock. In the face of this stark evidence, purohits in the land blame the education system for unemployment in the economy. They don’t ask how China, Korea, Thailand, Malaysia, Mauritius recently and Europe, over centuries, employed large increases in their labour force at rising levels of productivity. They did so because governments and entrepreneurs employed increasing populations. And Chauristan is distinguished by its repetitive kleptocratic governments, the scarcity of productive enterprises and the plenitude of unproductive labour.

The stranger exhaled a long breath, looked the young man in the eye and said: ‘Every prospect in this land pleases me but the dominant elites, whatever robes they wear, disgust’. And the traveller weary, wended his wayward way.

Opinion

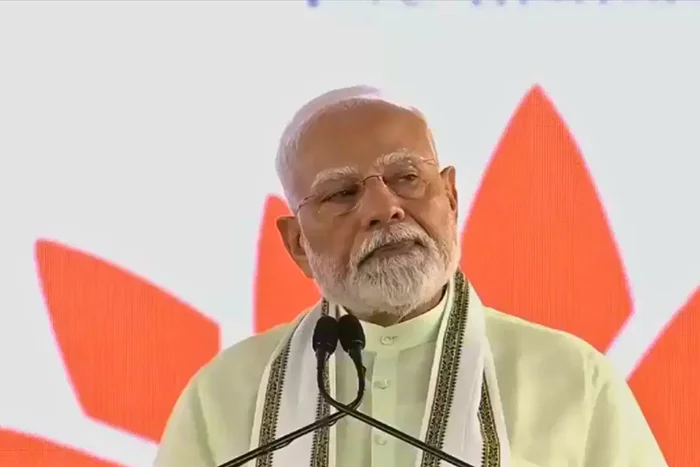

East awaits PM Modi’s visit

Former Vice Chancellor, Eastern University

President, Batticaloa District Chamber of Commerce, Industries, and Agriculture (BDCCIA)

It has been announced that Prime Minister of India Narendra Modi will be visiting Sri Lanka this week

It is also understood that the Prime Minister will meet the Sri Lankan leaders and hold formal meetings for discussion and action. There will likely be many issues on the agenda.

However, in a country with centuries-old ties to India and a significant population with strong affiliations to the Indian people, it will be a pity if the Prime Minister were to limit his engagements to government representatives alone. While parliamentarians may be an obvious choice for meetings, they have already engaged with Indian counterparts frequently. It would be more relevant for the Prime Minister to meet with representatives from business sectors, trade unions, and chambers of commerce to gain a broader and more practical understanding of Sri Lanka’s economic landscape and its relations with India.

The Eastern Province, in particular, has a special claim for attention. The Indian government has previously indicated its commitment to developing the East, and it is crucial to have direct discussions with communities in the Eastern Province to understand their issues and the agreements India is willing to pursue in relation to development. If this does not happen, the Eastern Province risks being, once again, misled by promises that never materialise—a mirage that keeps its people hopeful but ultimately unfulfilled. The East has long remained in the blind spot of development, acknowledged but never truly engaged, resulting in rising poverty and unemployment. It desperately needs a concrete programme for meaningful restoration and growth.

Batticaloa, in particular, lacks both the political backing that Ampara enjoys and the economic advantage of Trincomalee, which benefits from its harbour. Without targeted intervention, Batticaloa and other underserved areas in the East will continue to lag behind.

India needs to be more aware of the Eastern Province’s potential if it is to play a constructive role in its development. The region is naturally gifted with abundant resources, making it highly suitable for agriculture, fisheries, dairy farming, and tourism. It has vast lagoons, water bodies (Thonas) that connect to the sea, forests, and coastal ecosystems—elements that create immense economic potential. India has expertise in all these sectors, and tourism, in particular, could thrive with increased engagement, given the presence of Hindu temples of cultural and religious significance to the Indian population.

The dry zone, which dominates the North and East, shares similarities with Indian landscapes, making it ideal for cultivating crops and flowers with mutual trade agreements. Expanding fisheries within the 200-mile exclusive economic zone in the East, as well as harnessing ocean floor resources, presents a valuable opportunity for both India and the Eastern Province. Additionally, the large cattle population in the region could greatly benefit from India’s expertise in dairy production, as India is the world’s largest milk producer. The vast lagoons in the East rival those of Kerala, offering significant potential for inland tourism with boat services and associated activities.

The scope for development is clear, but what remains uncertain is India’s real commitment as a development partner, as stated by the Sri Lankan government. The Prime Minister’s visit must engage with all communities to ensure transparency and assurance that the East will not be left behind.

It is also crucial for the Eastern Province to be treated with the same level of importance as the North. The North has its own dedicated branch of the Indian High Commission, and the Malayagam community has established formal links with India. However, the Eastern Province appears to be the forgotten limb in this equation, and this neglect must be addressed.

The Eastern Province also continues to grapple with unresolved issues from the past conflict, including physical and cultural encroachments. The region was separated from the North through a court ruling two decades after the Indo-Sri Lanka Agreement’s merger of the North and East, yet it has never had the referendum required by law. India’s interests in Trincomalee and its harbour are well known, but the larger population of the Eastern Province is still awaiting India’s engagement in the region’s overall development. The people in the East want India to be truly committed to facilitating progress in their region, and will eagerly look to see that its actions reflect that commitment.

Let us hope that this visit brings a mirror of true reflection and action, rather than be another mirage of unfulfilled promises.

by Prof. Emeritus Thangamuthu Jayasingam

Opinion

Truth and Reconciliation Commission for Sri Lanka: Issues and challenges

D. Phil. (Oxford), Ph. D. (Sri Lanka);

Rhodes Scholar, Quondam Visiting Fellow of the Universities of Oxford, Cambridge and London;

Former Vice-Chancellor and Emeritus Professor of Law of the University of Colombo.

I. The Domestic and International Setting

The establishment of a Truth and Reconciliation Commission is a matter of lively interest across our society at this time. Developments a few days ago at the international level make this issue immediately relevant to the national interest of Sri Lanka.

The Minister of Foreign Affairs, Mr. Vijitha Herath, in his address at the 58th Session of the Human Rights Commission in Geneva in February this year, expressed interest in “the contours of a strong truth and reconciliation framework” and committed his government to “strengthening the work” in this field.

Current preoccupation with this concept has both a domestic and an international impetus. Within the country, the overwhelming confidence placed by the people of the North and East, as part of an Islandwide avalanche, in the current National People Power administration, impels the Government to focus, as a matter of priority, on national healing and reconciliation.

Beyond our shores, the expectation is equally urgent. The United Nations Human Rights Council, over the last decade, has adopted no fewer than 6 Resolutions on Sri Lanka. The pivotal Resolution, co-sponsored by Sri Lanka in 2015, called for a Commission for Truth, Justice, Reconciliation and Non-Recurrence. Subsequent Resolutions, expressing concern over lack of progress and the need for international accountability, introduced a new – and potentially hazardous – dimension. This consisted of the creation of a uniquely intrusive mechanism to gather and analyse evidence relating to Sri Lanka as a launching pad for further action in international tribunals.

Against the backdrop of these initiatives, a series of legislative measures have been taken in Sri Lanka – principally the enactment of the Office of Missing Persons Act of 2016, the Office for Reparations Act of 2018 and the Office of National Unity and Reconciliation Act of 2024. However, a hiatus remains with regard to the overarching mechanism of a Truth and Reconciliation Commission.

In attempting to complete the edifice, it is natural that policy makers in Sri Lanka should seek to derive assistance from the experience of South Africa, the home of probably the best-known Commission of this kind in the world. Inadequately and superficially researched, the proposed Sri Lankan legislation, published in the Gazette of 29 December 2023, suffers by comparison with legislation in other countries: it is marred by glaring omissions, and reflects shallowness of understanding of the aspirations which undergird successful instruments of reconciliation in our time.

II. The South African Experience Compared

The overlapping and contrasting features of Sri Lankan and South African legislation warrant close analysis.

(a) Territorial Application

There is a crucial difference in this regard. The mandate in South Africa embraces the whole nation without qualification (Preamble and section 3 of Act No. 34 of 1995). By contrast, the proposed mandate in Sri Lanka is operative throughout the Island, but only where the atrocities in question “were caused in the course of, or reasonably connected to, or consequent to the conflict which took place in the Northern and Eastern Provinces during the period 1983 to 2009, or its aftermath” (section 12(i)).

This is a limitation which cannot but affect the completeness of the Commission’s work. For instance, among the Commission’s powers is that of applying to a Magistrate “to excavate sites of suspected graves or mass graves and to act as observers at such excavations or exhumations” (section 13 (2c)). This is relevant also to areas outside the Northern and Eastern Provinces, and curtailment of the Commission’s mandate detracts from the overall balance and value of its work.

(b) Structural Framework

The South African legislation envisages 3 Committees specifically established alongside the Commission – the Committee on Human Rights Violations, the Committee on Amnesty and the Committee on Reparation and Rehabilitation. Each of these Committees has a statutory mandate and function, the role of each being clearly defined in relation to the Commission.

The Sri Lankan Bill is much less precise and clear-cut.The corresponding provision empowers the Commission to appoint panels consisting of not less than 3 members, the members being assigned to panels by the Chairperson of the Commission (section 7(2)). Unlike in South Africa, there is no indication of either the number of panels, or the subject matter entrusted to each panel. A tighter conceptual scheme, with explicit definition of identity and scope, is desirable at this conjuncture.

(c) Reconciliation and the Judiciary

Investigation which the Commission in Sri Lanka is authorised to undertake encompasses a wide range of activity including “extrajudicial killings, assassinations and mass murders” (section 12(g)(i)), “acts of torture” (section 12(g)(ii)) and “abduction, hostage taking and enforced disappearances” (section 12(g)(iv)). These are grave crimes in respect of which proceedings are instituted before the regular courts. In this event, should judicial proceedings, of a civil or criminal nature, be suspended until conclusion of the Commission’s investigations, or vice versa, or should they take place concurrently?

This is a matter of obvious practical importance which receives detailed consideration in South Africa, but not at all in Sri Lanka. For instance, where the person seeking amnesty before the relevant Committee in South Africa has a civil action in court pending against him, he may request suppression of the proceedings pending disposal of the application before the Committee (section 19(6)). The court may, after hearing all relevant parties, accede to this request. Similarly, a criminal action may be postponed in consultation with the Attorney-General of the relevant Province. These provisions serve the salutary purpose of averting the risk of conflicting orders by the courts and a Committee of the Commission in simultaneous proceedings. The Sri Lankan Bill fails to make any provision against this unacceptable contingency.

(d) Protection and Compellability

Discovery of truth requires the compulsory attendance of witnesses and the production of evidence before the Commission or its delegate. There is a the equally critical need, in subsequent proceedings, to protect witnesses against incrimination by testimony obtained through compulsion. These are competing objectives which need to be reconciled equitably.

This is achieved by the South African legislation: a person will be compelled to answer or produce evidentiary material having the potential to incriminate him, only if the Commission is satisfied that this course of action is “reasonable, necessary and justifiable” (section 31(2)). Moreover, the vital proviso is attached that the incriminating answer or evidence is inadmissible in criminal proceedings against the person providing it. This is a satisfactory result.

The position in Sri Lanka is quite otherwise. There is provision for the Commission to summon any person or to procure material (section 13(t) and (u)). This exists side by side with provision empowering the Attorney-General “to institute criminal proceedings in respect of any offence based on material collected in the course of an investigation by the Commission” (section 16(2)). Vulnerability is enhanced by the removal of protection conferred by the Evidence Ordinance (section 13(y)). In stark contrast with the position in South Africa, there is singular absence of any provision against self-incrimination in Sri Lanka.

(e) Amnesty

The basic purpose of Truth and Reconciliation Commissions around the world is to enable victims to come to terms with a deeply scarred past and to face the future with dignity and self-assurance. This is the gist of the Greek concept of Katharsis, or purging of the soul. Through full and candid disclosure, involving unburdening and relief, comes the expiation of guilt.

This is the context in which the idea of amnesty occupies a central place in the scheme of reconciliation. The Committee on Amnesty is the centrepiece of South African legislation. The primacy of its function is underlined by the provision that “No decision, or the process of arriving at such a decision, of the Committee on Amnesty shall be reviewed by the

Commission” (section 5(e)). The status of this Committee is unique, standing as it does apart from, and indeed above, the other Committees. An application for amnesty succeeds in South Africa if there is genuine contrition manifested in complete disclosure of all relevant facts (section 20(i)).

Sri Lankan law takes an entirely different course. Although the proposed Bill postulates, as one of the main objectives of the Commission “providing the people of Sri Lanka with a platform for truth telling” (section 12(d)), no provision whatever is made for conferment of amnesty in consequence of uninhibited disclosure. At the core of the law, there is a policy contradiction, with practical implications.

III. Political Will

Apart from these infirmities, cumulatively worrying, there is a negative factor of far greater importance.

When the draft legislation in Sri Lanka was published in January 2024, the response was less than unreservedly enthusiastic. This was mainly because of lingering doubts about the strength of political will underpinning this initiative. By no means the initial overture, this was yet another step in a long and disheartening sequence of events. The Lessons Learnt and Reconciliation Commission, the Udalagama Commission and the Paranagama Commission represented together a sterile endeavour, for well over a decade, to address the salient issues. The Bill impliedly concedes this. What is of particular significance is the inclusion, in Part VIII of the Bill, of a set of provisions entitled “Implementation of the Commission’s Recommendations”. The key provision requires the setting up of a Monitoring Committee (section 39) consisting of the Secretaries of 5 Ministries and 6 others, to submit to the President every 6 months reports which “shall include the reasons for non-implementation” (section 40(9)) by relevant entities. This is hardly likely to engender a high threshold of confidence.

A critical component of political will is commitment to community participation. This was much in evidence in South Africa even before Nelson Mandela’s accession to the Presidency. In my academic career, during visits to the University of the Witwatersrand and the University of Cape Town on lecture tours, I observed at first hand, the sustained efforts by leaders of South African academia to convince the corporate sector that structural change is the preferable alternative to unbridled anarchy.

As Minister of Justice, Ethnic Affairs and National Integration in the Government of President Chandrika Kumaratunga, I interacted closely with my counterparts,Dullah Omar, Minister of Justice and Mandela’s personal lawyer and Valli Moosa, Minister of Constitutional Affairs, who even used pictorial images, rather than the printed word, to convey the central message of reconciliation to the vast mass of the people, especially in the rural hinterland. This was very much the wind beneath the wings, and supplied the thrust for intense community involvement.

IV. Role of an Icon

Rising above all these considerations is a circumstance which was brought home to me vividly during my participation, as Minister of Foreign Affairs, in the Commonwealth Summit in Kigali, Rwanda, in 2022. On the sidelines of this event, I had the benefit of a discussion with my South African counterpart, Ms. Naledi Pandor, at the time Minister of International Relations and Cooperation. She shared with me her perspective that, whatever the South African process accomplished, was in considerable measure attributable to the towering stature of Archbishop Desmond Tutu who enjoyed remarkable prestige across the nation. An emblematic figure as the visible symbol of the process is, therefore, vital, the ideal choice probably being a personality bereft of a prominent political profile. Qualities of leadership are, in practice, of even greater value than the structural characteristics of the Commission.

V. Restorative Justice

The abiding inspiration of reconciliation mechanisms arises from the idea of restorative, as opposed to retributive, justice; but this concept has intrinsic limits. In the South African case, pride of place was given to sincere truth telling which would overcome hatred and the primordial instinct for revenge. The vehicle for giving effect to this was amnesty. Not infrequently, however, this opportunity was spurned. Despite the personal intervention of Mandela, former State President P. W. Botha was adamant in his refusal to appear before the Commission which he denounced as “a fierce unforgiving assault” on Afrikaaners. This sentiment struck a compliant chord in many leaders of the security and military establishment under the apartheid regime. Among them were General Magnus Malan, former Minister of Defence, and General Johan van der Merwe, former Commissioner of the South African Police.

Contemptuous refusal to appear before the Commission led to criminal prosecution. Eugene de Kock, commander of a police death squad, was convicted on multiple counts of murder. An interesting case is that of Security Branch officer, Joao Rodrigues, who was charged with murder 47 years after the death of anti-apartheid activist, Ahmed Timol, in police custody. When repentance and amnesty failed, criminal responsibility took over.

At the heart of the discourse is interplay among the ideas of truth, justice and reconciliation. Search for the right balance is the perennial dilemma. The basic conflict is between amnesty and accountability. A legitimate criticism of the South African experience is that it tended, on occasion, to give disproportionate attention to the former at the expense of the latter. It did happen that grave crimes went unpunished, leaving victims, after the trauma of reliving the past, profoundly unfulfilled.

Diverse cultures offer an array of choices. In Argentina, the power to grant amnesty was withheld from the Commission. In Colombia, disclosure resulted not in total exoneration but in mitigation of sentence. In Chile, prosecutions were feasible only after a prolonged interval since the dismantling of Augusto Pinochet’s dictatorship. In Peru, individual sanctions were studiedly relegated to major economic and societal transformation in the wake of the ravaging conflict with Sendero Luminoso (Shining Path).

An eclectic approach, affording the fullest scope for selection and imaginative adaptation, is the way forward. There is no size that fits all.

By Professor G. L. Peiris

Opinion

Gnana Moonesinghe- an appreciation

It was just over one month ago that Gnana Moonesinghe departed from this world after having lived a very fruitful life on this earth. It was indeed a privilege that Mallika and I came to know Gnana after we moved into Havelock City. During that short period, we became very close friends, along with another mutual friend of ours, Dr. Disampathy Subesinghe, who, too, was living in the same Tower after having come from the United Kingdom. Unfortunately, Dr. Subesinghe pre-deceased Gnana.

Gnana was a graduate of the University of Ceylon, Peradeniya having been at Peradeniya during the halcyon days of that University.

She tied the nuptial knot with Mangala Moonesinghe who was a very respected politician and who served as our High Commissioner in London and New Delhi. She was an exceptional hostess while being the wife of the High Commissioner. It was a very interesting coincidence that our second son, Anuke, had won a trip to New Delhi having won an All-Island essay competition about India while still a schoolboy. The team had met the High Commissioner and Gnana when they attended a reception hosted at the High Commission, where Gnana had been an exceptional hostess to the young boys.

Gnana was a member of many organisations and played an important role in all of them. In addition to these activities, she contributed to newspapers on varied subjects, especially relating to good governance and reconciliation. She was a keen player of scrabble and rummy with her friends and of course entertaining them to a meal if played at her home.

It was while in New Delhi that Gnana wrote and published a book titled “Thus have I heard…”in the year 2009 and she presented a copy to me). This book gives lucid descriptions of the Buddhist teachings of the Buddha and the places of interest in India with historical descriptions of what transpired in each place.

Gnana had brought up a very good daughter Avanthi and a son Sanath. She doted on her grandchildren and in turn they loved her. It was Avanthi and her husband, Murtaza who looked after Gnana during the last stages of her life.

We will miss Gana’s hospitality, soft spoken conversations, and the love that she used to emanate towards her friends.

HM NISSANKA WARAKAULLE

-

Sports3 days ago

Sports3 days agoSri Lanka’s eternal search for the elusive all-rounder

-

Features7 days ago

Features7 days agoCelebrating 25 Years of Excellence: The Silver Jubilee of SLIIT – PART I

-

News4 days ago

News4 days agoGnanasara Thera urged to reveal masterminds behind Easter Sunday terror attacks

-

Business7 days ago

Business7 days agoCEB calls for proposals to develop two 50MW wind farm facilities in Mullikulam

-

Business5 days ago

Business5 days agoAIA Higher Education Scholarships Programme celebrating 30-year journey

-

Features7 days ago

Features7 days agoNotes from AKD’s Textbook

-

News2 days ago

News2 days agoBid to include genocide allegation against Sri Lanka in Canada’s school curriculum thwarted

-

News3 days ago

News3 days agoComBank crowned Global Finance Best SME Bank in Sri Lanka for 3rd successive year