Opinion

A fable: Misappropriation Bill presented in Parliament of Sovereign Kleptocratic Republic of Chauristan

by Usvatte-aratchi

No, you will not find it among the five ‘Stan Countries’ in the massive spread of Eurasia. Go further south and further east until you meet a sizeable island, not quite utima thule. Ask any forlorn-looking young man in that land where cones on stupa nearly scrape the underbelly of heavens, ‘In this seemingly pleasant land, what is the profession where a person with no inherited wealth, no education, and no professional skills can amass vast wealth in less than five years?’ The young man turned to him as if the stranger were a gross ignoramus and answered, ‘Why silly, politics? This is where asinus rex est.’ ‘Did you say, a land where the donkey is king’? How so?’ asks the visitor. ‘By misappropriating public funds’, gravely replied the young man, ‘to continue which, there is today a Misappropriation Bill presented before the House. It is mainly for misappropriating public funds, first by misallocation’. ‘That is probably why those rich thieves thrive luxuriantly outside a jail. In other countries, such men and women are housed at state expense in jails and at somewhat less comfort than princely. The state owes at least that little to those geniuses, who brought such immense ill fame to this land.’

A few days ago, the Chaurisri, the president of the Chaurigrha (that is the name of the Parliament like the Knesset in Israel or the Duma in Japan) announced the first reading of the said Misappropriation Bill. Since 2005, the annual Misappropriation Bill has been the principal instrument used to plunder the revenue of the state. Revenue (misnamed government income) of the state comprises tax revenue, government income and proceeds from loans raised by the government, each year. The misappropriation has been so gross, systematic, persistent and thorough that the kleptocratic republic won infamy in international fora including lending institutions, as a dark hole that sank money that should have benefited the common people of that country. As was inevitable, the Treasury was empty and the people were left with only foul air to breathe. Yet, Chauripurohit (Minister of Finance), who is also Chauripathi, announced in Chaurigrha that corruption in that land was but ‘a fable’. If the purohit spoke the truth, which he betimes does, then the truth in Chauristan is incredibly fabulous (Fable and fabulous come from the same Latin word ‘fabula.) At the bottom of that dark hole sat a spreading family of fat cats whose skills were confined to deception and corruption. They could not catch so much as a mouse who dared to pilfer some of the Swiss cheese they had imported to fatten the cats. One of the lenders to Chauristan was so concerned that its funds should not be misappropriated, that it appointed its own accountants and auditors when lending to the government of Chauristan. Knowledgeable taxpayers avoided and evaded tax payments because they knew that their taxes only would fatten the family of cats who would litter more. Other taxpayers and potential taxpayers flew out in flocks. The cost of those preventive measures became a part of the loan that the taxpayers of Chauristan would eventually repay.

Three parties misappropriated funds for their benefit. First the members of the Executive Branch of the government from the highest to the lowest. Those sums were fittingly very high. It is commonly averred that they siphoned 20 percent of any loan proceeds and of the price of large contracts. The contractors themselves plundered public funds by using sub-standard material, cheating on measurements and abandoning projects fully paid up but only partly done. There were three important consequences. First, the highest in the executive branch who decided on which projects or which version of a project would be selected, always and inevitably opted for the highest-priced project on offer. The reasoning was quite simple: 20 percent of $20 million raised a bribe of $4 million and 20 percent of 100 million gave $20 million and some loans exceeded a few billion US dollars. There were more than a few who shared each loot. Second, all large-scale projects were financed with loans from overseas with some marginal contribution from tax revenue. The Family avoided accepting offers of projects from countries and companies that would not collude with the Family to offer the cut that the Family wanted and further, deposit the bribe in banks outside Chauristan. So solicitous were they for the good name of Chauristan that they kept their gold securely in a locked Pandora’s Box. The most egregiously corrupt instance was when the government of Chauristan turned down a Light Rail Project offered almost free by a friendly government. Thirdly, as projects which had been accepted became either completely or partially unproductive, the burden of repayment fell on taxpayers, whose income had not increased at all. If you built a house and nobody took it on rent, you would pay the loan to the bank from your monthly salary and that at the cost of milk for your baby. The responsibility is yours for having put up that house in a devil’s cemetery. In reaction, when the burden of taxation became too heavy to bear, some refused to earn beyond a certain upper limit, some packed their bags and looked for refuge overseas and the very poor withered on the vine like grapes in winter in northern Italy. Loans were used to build 40 foot-wide roads on which crocodiles slumbered in the sun and buffaloes gambolled idly, airports, where hangars stored rice and sheltered no airplanes, ports where ships did not call, theatres where ghosts (not Ibsen’s) found permanent residence and where tall columns kept watchful guard over teals nesting in the bushes near the Beira. They did not produce an income adequate to service the loans and people in other sectors were starved to pay off loans while the cats and (Kaputas) crows grew visibly fatter. When those other sectors were destroyed wilfully by one member of the Family and by circumstances well beyond the control of the Family, the economy fell with a thud and woeful consequences fell upon the public. Yet, the cats grew fatter. Purposely and wilfully, one member of the Family denied large sums of tax revenue to the government and diverted that flow to Family friends who also had helped pay for their election to office and also to evade justice. The problem was further complicated as some of these loans were from overseas and had to be serviced with foreign currency. The value of the domestic currency in both foreign exchange and domestic markets tanked. Price inflation soared higher and faster than a kite in August on Galle Face Green.

The second group that misappropriated funds were rich traders who had power and influence over the said Family. Those had gained from the losses to the government treasury and at the same time to the public. The current Misappropriation Bill provides several honeypots that the kleptocrats must already savour. Government enterprises making good profits are up for sale to the private sector, even to the very private sector enterprises and individuals who had plundered the public purse. The capital that the Fat Cats publicly denied owning will suddenly emerge from where they were hidden, and black money will suddenly whiten and glisten and so will be born the Sri Lanka oligarchs. Wealth now hidden in properties in Australia, Europe, Africa, islands in the Indian Ocean and in the Caribbean will flow into Chauristan. Several miracles will occur simultaneously: black money will glisten and whiten blindingly; plunderers in kapati suits will fatten further in Parisian suits and Italian shoes; Sri Lanka’s capital account in the balance of payments will be in the black temporarily. It will be perestroika all over again but in a teacup. Voters need to understand these shenanigans well and elect representatives who will confine plunderers in jail and recover the loot forthwith.

The third group of plunderers was bureaucrats at very high levels. Senior Advisors to presidents, the prime minister and other ministers were notoriously corrupt. Many were caught with their sticky fingers in the kitty but skillful lawyering and unscrupulous politicians installed them back in higher positions and with substantially higher pay. And so merrily did they plunder; the Chauripurohit was right; it was fabulous (fable-like).

The Misappropriation Bill was presented in Chaurigrha as if there was only a macroeconomic problem ailing the economy. All the talk was about primary balances and stability in the economy. There was not a word about the horrors committed by the misallocation of resources. They were fables: my left cleft foot! Everyone breathed the macro-economic vapour and in the ensuing stupor forgot that it was misallocating resources and mismanaging individual projects that summed up to the macro-economic disasters. Thirteen years after the war in Chauristan, defence expenditure keeps on rising at the cost of other sectors including education and health. It is true that defence forces employ large numbers who would otherwise go unemployed and that these young men and women dig trenches and fill them back. Some of them have started making bags for politicians; a few will carry them. But what is the invasion against which the armed forces ever defended Chauristan? Chauristan armed forces cannot withstand for a fortnight even a minor invasion by sea, air and land from any but the smallest powers in its neighbourhood. They failed miserably to prevent a well-planned attack on worshippers at prayer in church on Easter Sunday in 2019, reliable information from other countries notwithstanding. Defend the country: flipping claptrap (Andy Capp might have said). The armed forces in Chauristan arefor the protection of the government against its own people and not for the protection of the state against other states. (One way of confounding the public mind is to confuse the use of the terms state and government so that when people attack a government it is dressed up by government as an attack on the state. Aragalaya attacked the government then in power and not the state of Sri Lanka. They were not traitors to the state of Sri Lanka. In contrast, Eritrea became a separate state after she broke away from Ethiopia. The people who rebelled were traitors to the state of Ethiopia.) Chauripurohit during the budget debate threatened to use armed forces to protect his government from the wrath of the public . That call, in principle, is problematic. After all the armed forces are of the people. But the armed forces are there to maintain public order. Good judgment is of the essence Why not call that outfit the Ministry of Internal Security? Why call a rose by another name?

There is one organ of government that will protect the people from depredation by the government: the judiciary. The judiciary has neither sleuths nor guns nor tanks. The judiciary needs the active support of some important parts of the executive to bring enemies of the people (Ibsen, again) to justice. When the executive fails in its duties and, in fact, colludes with other parts of government to harm the governed, the judiciary is helpless. Allocation is determined by the executive branch of government which can starve the judicial branch of resources. It is the function of the legislature to correct such misallocation.

Allocating massive sums over two decades to projects that overran their originally budgeted resources and construction periods ensured that those projects would bring about waste of capital and minimal rates of economic growth. Of some 5,000 head of cattle imported from New Zealand to Chauristan 90 percent died within a year. Good project management could have eliminated all this waste. In fact, some parts of Chaurigrha brought out these dreadful facts but the mass in that august assembly could not make the connections.

The government of Chauristan is a swamp that drains the flood of unemployed in the economy. Politicians continually widen and deepen that swamp to keep their noses above water. There is roughly one government employee for every 15 persons in the population. There is roughly one teacher per 15 students in schools. More than 20 percent of the labour force in the country work overseas and the recent higher rate of outflow from the country is raising the stock. In the face of this stark evidence, purohits in the land blame the education system for unemployment in the economy. They don’t ask how China, Korea, Thailand, Malaysia, Mauritius recently and Europe, over centuries, employed large increases in their labour force at rising levels of productivity. They did so because governments and entrepreneurs employed increasing populations. And Chauristan is distinguished by its repetitive kleptocratic governments, the scarcity of productive enterprises and the plenitude of unproductive labour.

The stranger exhaled a long breath, looked the young man in the eye and said: ‘Every prospect in this land pleases me but the dominant elites, whatever robes they wear, disgust’. And the traveller weary, wended his wayward way.

Opinion

What BNP should keep in mind as it assumes power

BNP rightly deserves our congratulations for winning a decisive victory in the 13th parliamentary election. This outcome reflects an unequivocal mandate that is both politically and historically significant. Coming as it does at a critical point in Bangladesh’s democratic journey, this moment marks more than a change of government; it signals a renewed public resolve to restore democratic norms, accountability, and institutional integrity.

The election came after years of severe distrust in the electoral process, questions over legitimacy, and institutional strain, so the poll’s successful conduct has reinforced trust in the process as well as the principle that governments derive authority from the consent of the governed. For quite some time now, Bangladesh has faced deep polarisation, intolerance, and threats to its democratic foundations. Regressive and anti-democratic tendencies—whether institutional, ideological, or political—risked steering the country away from its foundational goals. BNP’s decisive victory can therefore be interpreted as a call to reverse this trajectory, and a public desire for accountable, forward-looking governance rooted in liberal democratic principles.

However, the road ahead is going to be bumpy, to put it mildly. A broad mandate alone cannot resolve deep-rooted structural problems. The BNP government will likely continue to face economic challenges and institutional constraints for the foreseeable future. This will test its capacity and sincerity not only to govern but also to transform the culture of governance in the country.

Economic reform imperatives

A key challenge will be stabilising the economy, which continues to face mounting pressures: growth has decelerated, inflation has eroded people’s purchasing power, foreign exchange reserves remain low, and public finances are tight. External debt has increased significantly in recent years, while the tax-to-GDP ratio has fallen to historically low levels. State-owned enterprises and the banking sector face persistent structural weaknesses, and confidence among both domestic and international investors remains fragile.

The new government should begin by restoring macroeconomic discipline. Containing inflation will need close coordination across ministries and agencies. Monetary policy must remain cautious and credible, free from political interference, while fiscal policy should prioritise stability rather than expand populist spending.

Tax reform is also unavoidable. The National Board of Revenue requires comprehensive modernisation, digitalisation, and total compliance. Broadening the tax base, especially by bringing all high-income groups and segments of the informal economy into the formal system, is crucial. Over time, reliance on indirect taxes such as value-added tax and import duties should be reduced, paving the way for a more progressive direct tax regime.

Banking sector reform is equally crucial. Proper asset quality reviews and regulatory oversight are necessary to rebuild confidence in the sector. Political patronage within the financial institutions must end. Without a resilient financial system, private investment cannot recover. As regards growth, the government should focus on diversifying exports beyond ready-made garments and deepening integration into regional value chains. Attracting foreign direct investment will depend on regulatory predictability and improvements in logistics and energy reliability. Ambitious growth targets must be matched by realistic implementation capacity.

Political Challenges

Distrust among political actors, partly fuelled by fears of retribution and violence, is a reality that may persist. BNP will face pressure from its supporters to act quickly in addressing perceived injustices, but good governance demands restraint. If the new government resorts to or tolerates exclusion or retaliation, it will risk perpetuating the very cycle it has condemned.

Managing internal party discipline will also be crucial, as a large parliamentary majority can sometimes lead to complacency or factional rivalry. Strong leadership will be required to maintain unity while allowing constructive internal debate. BNP must also rebuild trust with minority communities and vulnerable groups. Elections often heighten anxieties among minorities, so a credible commitment to equal citizenship is crucial. BNP’s political maturity will also be judged by how it treats or engages with its opponents. In this regard, Chairman Tarique Rahman’s visits to the residences of top opposition leaders on Sunday marked a positive gesture, one that many hope will withstand the inevitable pressures or conflicts over governance in the coming days.

Strengthening democratic institutions

A central promise of this election was to restore democracy, which must now translate into concrete institutional reforms. Judicial independence needs constant safeguarding. Which means that appointment, promotion, and case management processes should be insulated from political influence. Parliamentary oversight committees must also function effectively, and the opposition’s voice in parliament must be protected.

Electoral institutions also need reform, particularly along the lines of the July Charter. Continued credibility of the Election Commission will depend on transparency, professional management, and impartiality. Meanwhile, the civil service must be depoliticised. Appointments based on loyalty rather than merit have long undermined governance in the country. So the new administration must work on curtailing the influence of political networks to ensure a professional, impartial civil service. Media reform and digital rights also deserve careful attention. We must remember that democratic consolidation is built through institutional habits, and these habits must be established early.

Beyond winner-takes-all

Bangladesh’s politics has long been characterised by a winner-takes-all mentality. Electoral victories have often resulted in monopolisation of power, marginalising opposition voices and weakening checks and balances. If BNP is serious about democratic renewal, it must consciously break with this tradition. Inclusive policy consultations will be a good starting point. Major economic and constitutional reforms should be based on cross-party dialogue and consensus. Appointments to constitutional bodies should be transparent and consultative, and parliamentary debates should be done with the letter and spirit of the July Charter in mind.

Meeting public expectations

The scale of public expectations now is naturally immense. Citizens want economic relief, employment opportunities, necessary institutional reforms, and improved governance. Managing these expectations will be quite difficult. Many reforms will not yield immediate results, and some may impose short-term costs. So, it is imperative to ensure transparent communication about the associated timelines, trade-offs, and fiscal constraints.

Anti-corruption efforts must be credible and monitored at all times. Measures are needed to strengthen oversight institutions, improve transparency in public procurement, and expand digital service delivery to reduce opportunities for rent-seeking. Governance reform should be systematic, not selective or politically driven. Tangible improvements are urgently needed in public service delivery, particularly in health, education, social protection, and local government.

Finally, a word of caution: BNP’s decisive victory presents both opportunities and risks. It can enable bold reforms but it also carries the danger of overreach. The key deciding factor here is political judgment. The question is, can our leaders deliver based on the mandate voters have given them? (The Daily Star)

Dr Fahmida Khatun is an economist and executive director at the Centre for Policy Dialogue (CPD). Views expressed in the article are the author’s own.

Views expressed in this article are the author’s own.

by Fahmida Khatun

Opinion

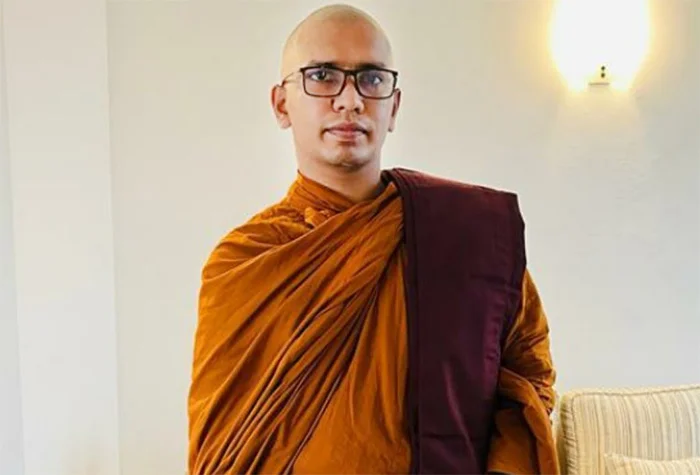

Why religion should remain separate from state power in Sri Lanka: Lessons from political history

Religion has been an essential part of Sri Lankan society for more than two millennia, shaping culture, moral values, and social traditions. Buddhism in particular has played a foundational role in guiding ethical behaviour, promoting compassion, and encouraging social harmony. Yet Sri Lanka’s modern political history clearly shows that when religion becomes closely entangled with state power, both democracy and religion suffer. The politicisation of religion especially Buddhism has repeatedly contributed to ethnic division, weakened governance, and the erosion of moral authority. For these reasons, the separation of religion and the state is not only desirable but necessary for Sri Lanka’s long-term stability and democratic progress.

Sri Lanka’s post-independence political history provides early evidence of how religion became a political tool. The 1956 election, which brought S. W. R. D. Bandaranaike to power, is often remembered as a turning point where Sinhala-Buddhist nationalism was actively mobilised for political expedience. Buddhist monks played a visible role in political campaigning, framing political change as a religious and cultural revival. While this movement empowered the Sinhala-Buddhist majority, it also laid the foundation for ethnic exclusion, particularly through policies such as the “Sinhala Only Act.” Though framed as protecting national identity, these policies marginalised Tamil-speaking communities and contributed significantly to ethnic tensions that later escalated into civil conflict. This period demonstrates how religious symbolism, when fused with state power, can undermine social cohesion rather than strengthen it.

The increasing political involvement of Buddhist monks in later decades further illustrates the risks of this entanglement. In the early 2000s, the emergence of monk-led political parties such as the Jathika Hela Urumaya (JHU) marked a new phase in Sri Lankan politics. For the first time, monks entered Parliament as elected lawmakers, directly participating in legislation and governance. While their presence was justified as a moral corrective to corrupt politics, in practice it blurred the boundary between spiritual leadership and political power. Once monks became part of parliamentary debates, policy compromises, and political rivalries, they were no longer perceived as neutral moral guides. Instead, they became political actors subject to criticism, controversy, and public mistrust. This shift significantly weakened the traditional reverence associated with the Sangha.

Sri Lankan political history also shows how religion has been repeatedly used by political leaders to legitimise authority during times of crisis. Successive governments have sought the public endorsement of influential monks to strengthen their political image, particularly during elections or moments of instability. During the war, religious rhetoric was often used to frame the conflict in moral or civilisational terms, leaving little room for nuanced political solutions or reconciliation. This approach may have strengthened short-term political support, but it also deepened ethnic polarisation and made post-war reconciliation more difficult. The long-term consequences of this strategy are still visible in unresolved ethnic grievances and fragile national unity.

Another important historical example is the post-war period after 2009. Despite the conclusion of the war, Sri Lanka failed to achieve meaningful reconciliation or strong democratic reform. Instead, religious nationalism gained renewed political influence, often used to silence dissent and justify authoritarian governance. Smaller population groups such as Muslims and Christians in particular experienced growing insecurity as extremist groups operated with perceived political protection. The state’s failure to maintain religious neutrality during this period weakened public trust and damaged Sri Lanka’s international reputation. These developments show that privileging one religion in state power does not lead to stability or moral governance; rather, it creates fear, exclusion, and institutional decay.

The moral authority of religion itself has also suffered as a result of political entanglement. Traditionally, Buddhist monks were respected for their distance from worldly power, allowing them to speak truth to rulers without fear or favour. However, when monks publicly defend controversial political decisions, support corrupt leaders, or engage in aggressive nationalist rhetoric, they risk losing this moral independence. Sri Lankan political history demonstrates that once religious figures are seen as aligned with political power, public criticism of politicians easily extends to religion itself. This has contributed to growing disillusionment among younger generations, many of whom now view religious institutions as extensions of political authority rather than sources of ethical guidance.

The teachings of the Buddha offer a clear contrast to this historical trend. The Buddha advised rulers on ethical governance but never sought political authority or state power. His independence allowed him to critique injustice and moral failure without compromise. Sri Lanka’s political experience shows that abandoning this principle has harmed both religion and governance. When monks act as political agents, they lose the freedom to challenge power, and religion becomes vulnerable to political failure and public resentment.

Sri Lanka’s multi-religious social structure nurtures divisive, if not separatist, sentiments. While Buddhism holds a special historical place, the modern state governs citizens of many faiths. Political history shows that when the state appears aligned with one religion, minority communities feel excluded, regardless of constitutional guarantees. This sense of exclusion has repeatedly weakened national unity and contributed to long-term conflict. A secular state does not reject religion; rather, it protects all religions by maintaining neutrality and ensuring equal citizenship.

Sri Lankan political history clearly demonstrates that the fusion of religion and state power has not produced good governance, social harmony, or moral leadership. Instead, it has intensified ethnic divisions, weakened democratic institutions, and damaged the spiritual credibility of religion itself. Separating religion from the state is not an attack on Buddhism or Sri Lankan tradition. On the contrary, it is a necessary step to preserve the dignity of religion and strengthen democratic governance. By maintaining a clear boundary between spiritual authority and political power, Sri Lanka can move toward a more inclusive, stable, and just society one where religion remains a source of moral wisdom rather than a tool of political control.

In present-day Sri Lanka, the dangers of mixing religion with state power are more visible than ever. Despite decades of experience showing the negative consequences of politicised religion, religious authority continues to be invoked to justify political decisions, silence criticism, and legitimise those in power. During recent economic and political crises, political leaders have frequently appeared alongside prominent religious figures to project moral legitimacy, even when governance failures, corruption, and mismanagement were evident. This pattern reflects a continued reliance on religious symbolism to mask political weakness rather than a genuine commitment to ethical governance.

The 2022 economic collapse offers a powerful contemporary example. As ordinary citizens faced shortages of fuel, food, and medicine, public anger was directed toward political leadership and state institutions. However, instead of allowing religion to act as an independent moral force that could hold power accountable, sections of the religious establishment appeared closely aligned with political elites. This alignment weakened religion’s ability to speak truthfully on behalf of the suffering population. When religion stands too close to power, it loses its capacity to challenge injustice, corruption, and abuse precisely when society needs moral leadership the most.

At the same time, younger generations in Sri Lanka are increasingly questioning both political authority and religious institutions. Many young people perceive religious leaders as participants in political power structures rather than as independent ethical voices. This growing scepticism is not a rejection of spirituality, but a response to the visible politicisation of religion. If this trend continues, Sri Lanka risks long-term damage not only to democratic trust but also to religious life itself.

The present moment therefore demands a critical reassessment. A clear separation between religion and the state would allow religious institutions to reclaim moral independence and restore public confidence. It would also strengthen democracy by ensuring that policy decisions are guided by evidence, accountability, and inclusive dialogue rather than religious pressure or nationalist rhetoric. Sri Lanka’s recent history shows that political legitimacy cannot be built on religious symbolism alone. Only transparent governance, social justice, and equal citizenship can restore stability and public trust.

Ultimately, the future of Sri Lanka depends on learning from both its past and present. Protecting religion from political misuse is not a threat to national identity; it is a necessary condition for ethical leadership, democratic renewal, and social harmony in a deeply diverse society.

by Milinda Mayadunna

Opinion

NPP’s misguided policy

Judging by some recent events, starting with the injudicious pronouncement in Jaffna by President Anura Kumara Dissanayake and subsequent statements by some senior ministers, the government tends to appease minorities at the expense of the majority. Ill-treatment of some Buddhist monks by the police continues to arouse controversy, and it looks as if the government used the police to handle matters that are best left to the judiciary. Sangadasa Akurugoda concludes his well-reasoned opinion piece “Appeasement of separatists” (The island, 13 February) as follows:

“It is unfortunate that the President of a country considers ‘national pride and patriotism’, a trait that every citizen should have, as ‘racism’. Although the President is repeating it like a mantra that he will not tolerate ‘racism’ or ‘extremism’ we have never heard him saying that he will not tolerate ‘separatism or terrorism’.”

It is hard to disagree with Akurugoda. Perhaps, the President may be excused for his reluctance to refer to terrorism as he leads a movement that unleashed terror twice, but his reluctance to condemn separatism is puzzling. Although most political commentators consider the President’s comment that ‘Buddhist go to Jaffna to spread hate’ to be callous, the head of an NGO heaped praise on the President for saying so!

As I pointed out in a previous article, puppet-masters outside seem to be pulling the strings (A puppet show? The Island, 23 January) and the President’s reluctance to condemn separatism whilst accusing Buddhists of spreading hatred by going to Jaffna makes one wonder who these puppeteers are.

Another incident that raises serious concern was reported from a Buddhist Temple in Trincomalee. The police removed a Buddha statue and allegedly assaulted Buddhist priests. Mysteriously, the police brought back the statue the following day, giving an absurd excuse; they claimed they had removed it to ensure its safety. No inquiry into police action was instituted but several Bhikkhus and dayakayas were remanded for a long period.

Having seen a front-page banner headline “Sivuru gelawenakam pahara dunna” (“We were beaten till the robes fell”) in the January 13th edition of the Sunday Divaina, I watched on YouTube the press briefing at the headquarters of the All-Ceylon Buddhist Association. I can well imagine the agony those who were remanded went through.

Ven. Balangoda Kassapa’s description of the way he and the others, held on remand, were treated raises many issues. Whether they committed a transgression should be decided by the judiciary. Given the well-known judicial dictum, ‘innocent until proven guilty’, the harassment they faced cannot be justified under any circumstances.

Ven. Kassapa exposed the high-handed actions of the police. This has come as no surprise as it is increasingly becoming apparent as they are no longer ‘Sri Lanka Police’; they have become the ‘NPP police’. This is an issue often editorially highlighted by The Island. How can one expect the police to be impartial when two key posts are held by officers brought out of retirement as a reward for canvassing for the NPP. It was surprising to learn that the suspects could not be granted bail due to objections raised by the police.

Ven. Kassapa said the head of the remand prison where he and others were held had threatened him.

However, there was a ray of hope. Those who cry out for reconciliation fail to recognise that reconciliation is a much-misused term, as some separatists masquerading as peacemakers campaign for reconciliation! They overlook the fact that it is already there as demonstrated by the behaviour of Tamil and Muslim inmates in the remand prison, where Ven. Kassapa and others were kept.

Non-Buddhist prisoners looked after the needs of the Bhikkhus though the prison chief refused even to provide meals according to Vinaya rules! In sharp contrast, during a case against a Sri Lankan Bhikkhu accused of child molestation in the UK, the presiding judge made sure the proceedings were paused for lunch at the proper time.

I have written against Bhikkhus taking to politics, but some of the issues raised by Ven. Kassapa must not be ignored. He alleges that the real reason behind the conflict was that the government was planning to allocate the land belonging to the Vihara to an Indian businessman for the construction of a hotel. This can be easily clarified by the government, provided there is no hidden agenda.

It is no secret that this government is controlled by India. Even ‘Tilvin Ayya’, who studied the module on ‘Indian Expansionism’ under Rohana Wijeweera, has mended fences with India. He led a JVP delegation to India recently. Several MoUs or pacts signed with India are kept under wraps.

Unfortunately, the government’s mishandling of this issue is being exploited by other interested parties, and this may turn out to be a far bigger problem.

It is high time the government stopped harassing the majority in the name of reconciliation, a term exploited by separatists to achieve their goals!

By Dr Upul Wijayawardhana

-

Life style6 days ago

Life style6 days agoMarriot new GM Suranga

-

Business5 days ago

Business5 days agoMinistry of Brands to launch Sri Lanka’s first off-price retail destination

-

Features6 days ago

Features6 days agoMonks’ march, in America and Sri Lanka

-

Features6 days ago

Features6 days agoThe Rise of Takaichi

-

Features6 days ago

Features6 days agoWetlands of Sri Lanka:

-

News6 days ago

News6 days agoThailand to recruit 10,000 Lankans under new labour pact

-

News6 days ago

News6 days agoMassive Sangha confab to address alleged injustices against monks

-

Sports2 days ago

Sports2 days agoOld and new at the SSC, just like Pakistan