Features

My Cricketing Journey, From Big Dreams To Big Matches

Michael Wille died in Australia a few days ago and his funeral will take place on Dec. 6

By Michael Wille

I have been asked to write an article about my cricketing journey from Colombo to Melbourne. I have some reservations about how relevant my article will be. However, I trust that it will serve essentially as an insight to the exhilarating schoolboy cricketing era of the 1950s.I debuted for Royal in ’54 and captained in ’57. A couple of weeks after the Royal-Thomian I migrated to Australia, and was the first Sri Lankan to play District (Grade) cricket in Melbourne.

In the ‘50s, Sri Lanka was far from attaining test status. Sri Lanka possessed great players such Mahadevan Sathasivam, F C de Saram, C I Gunasekera, Vernon Prins, and Mike Tissera, et al. The only exposure to international cricket that Sri Lanka had was a one-day friendly played when the English or Australian teams passed through Colombo on their way to Australia or England every two years.

In Australia at that time the game was purely amateur. Today, Sri Lanka has achieved test status and cricket is professional in both countries and the standard of cricket is considerably higher, particularly fielding.

Maybe my article should be regarded as no more than providing some insights into specific schoolboy cricketing encounters in the ‘50s, magnificent experiences that have now become wonderful memories of glorious days in the sun among some incredibly talented and sporting cricketers.

From the time I can remember, Sri Lanka was cricket mad. It was the only game in town, with the Royal-Thomian (RT), Josephian-Peterite and Ananda-Nalanda big matches being the centrepiece of the island’s sporting calendar. I attended my first RT at the iconic Colombo Oval in 1947 at the age of nine, I will never forget the experience. The flags waved by the supporters of the rival schools, the gaily coloured dresses of the girls, the raucous singing from the Mustang tent and the beating of rabanas (the papare band) gave the match a carnival atmosphere. Records show the Royalists won the game and a happy nine-year-old went home dreaming that one day he would be playing in the match.

I joined Royal in 1951, the RT of that year was one of the most exciting in the history of the game and was described as “the impossible finish of ‘51”. Royal, the underdogs snatched victory in the dying moments of the game. The Thomians had Roger Inman, Jayalingam and P I Pieris but the cool head of Vairavanathan (the Royal captain) saved the day for Royal. I left the ground with an even stronger desire to play in this great match.

I came a step closer of achieving my dreams when, as a 15-year-old, I was selected to join the First XI squad in the third term of ‘53. Nirmalingam was captain and we had a very strong squad with ten coloursmen, including Ubaya de Silva, “Frecko” Kreltzsheim, Ranjit de Silva and Fitzroy Crozier. The freshers were Brendon Gunaratne, Selvi Perinpanayagam and I. Dr Barney Gunasekera was the coach, and Harold Samaraweera the cricket master.

I interrupt my narrative to pay homage to two men who have had a massive influence on my cricket and my life, namely Barney and Harold.

In Sri Lanka, we tended to idolize and hold in awe men who had outstanding sporting success. In 1930, Barney playing in the big match, broke the record by scoring 130 runs and taking nine wickets. This match went down in history as Barney’s Match.

Barney was not really a cricket coach in a technical sense. He was more a philosopher with an interest in the mental aspects of the game. I cannot recall him talking to me about batting technique. One afternoon he said to me: “Michael, just play your normal game and don’t look at the scoreboard. I guarantee that if you do that and bat for three hours you will score a century.” I did just that in the RT of 1957, when captain, and scored a century.

Barney was a self-effacing man with a whimsical sense of humour and he treated everyone with respect. Barney had coached for many years and was highly respected by all of us. We would have walked over hot coals for him.Harold was my under-14 coach, my form master in Form 3 and now the cricket master of the First XI so I knew him very well. Harold was an enthusiastic and happy guy who wore his heart on his sleeve. At Royal, we were a bit elitist and because Harold had not played for one of the big schools we tended to underestimate his advice. He was very knowledgeable on cricket and was a great help to me when I was captain. Harold and Barney have passed on and I often think of them with love and gratitude.

After the first practice session, Barney addressed the squad. He said he believed that to play for Royal was an honour, he believed it was essential that we played as a team, and he believed it was important that we played within the rules and the spirit of the game. He said that if anyone did not believe in these three pillars than he did not want that boy in the squad. Very inspirational stuff!

To a Royalist (or Thomian) the RT is the Holy Grail but there were some other matches that also had a long tradition of fierce competition. One of these was the Wesley encounter. In 1954, Wesley had a strong side – the Fuard brothers, the Adhihetty brothers, Samsudeen, Chapman and Neil Gallagher to name a few.

Nirma won the toss, we batted and made about 200. M. Wille ct Chapman b Fuard 1. Abu was too good for me.

Miraculously we dismissed Wesley for 39. Unfortunately, I cannot recall who took the wickets. Nirma enforced the follow on and the Wesleyites did better in their second dig, avoiding an innings defeat, but leaving us with about 40 to win. It should have been a piece of cake but Lou Adhihetty and Samsudeen had other ideas and made us earn every run.

I understand that in later life Lou became heavily involved in the Christian church. But he showed no Christian brotherly love that afternoon. Samsudeen and Lou subjected us to a barrage of bouncers, one of which hit Rabindran in the face. Rabindran dropped like a sack of potatoes and there was blood all over the place. I was padded up and trembling in my boots. I prayed to all the gods Christian, Hindu, Buddhist, Muslim and a few others that I invented that I would not have to go in. My prayers were answered as our early batsmen weathered the storm and we won a hard-fought game by a comfortable margin.

Later on I was awarded my “colours” along with Brendon and Selvi. There is nothing more satisfying than to realise a dream one has worked very hard to achieve. The ‘54 RT, unfortunately, like the four I played in, ended in a draw.

Off the first ball of the match their star batsman, Tyrell Gauder, was given not out to a catch behind the wicket. You could hear the snick at the Borella junction. It was a shocking decision. Nirma looked at the umpire and walked back to his mark. Tyrell shrugged his shoulder as if to say, “What can I do.” We got on with the game. No histrionics. The other highlights were a brilliant 69 by Nirma before he ran himself out and a rearguard action from the Thomians to save the match, including a fighting 48 from Michael Tissera giving an indication of things to come.

After the match, the Principal of Royal and the Warden of S. Thomas’ hosted a dinner for the two teams. We could not wait for this to be over so that, according to custom and practice, we could paint the town red. First stop the Liberty cinema, owned by the Cader family. Zacroff was playing for S. Thomas’, and everything, bar included, was on the house. The teams then adjourned to the CR & FC as guests of some reprobate old boys of both schools. Last stop, Galle Face Green for a sing-song and a few bottles of beers. Home at about 5am.

I really believe that this bonding led to a great spirit of camaraderie between the teams and was the start of many lifelong friendships, which was a hallmark of schoolboy team sport at that time.

Ranjit de Silva captained in ‘55. In ‘54 I had batted at No. 6, and I was hoping to talk Ranjit into letting me bat at No. 4. After the first practice and after Barney had made his speech he turned to what he termed “housekeeping matters”. He called for a volunteer to open batting with Selvi. Nobody spoke. I took a great interest in my boots and avoided eye contact with everybody. Suddenly a voice pipes up, “Michael used to open in the under-14s”. I could have killed him. Quick as a flash, Barney said, “Thanks Michael, that’s settled then.” So began my career as an opening batsman.

The ‘55 season started poorly as we were comprehensively beaten by St Anthony’s at Katugastota, ACM Lafir, who was playing for Ceylon at the time, made a century, Another superstar we encountered was Clive Inman. Clive was captain of St Peter’s and after leaving school followed Stanley Jayasinghe to England to play as a professional in the Lancashire League.

We played Wesley at Reid Avenue. Lou was captain of Wesley and obviously had not forgiven us for beating them the previous year. We batted first and faced some terrific bowling plus some chatter from Lou and Samsudeen. It was hard to score runs. I called Selvi for a stupid single. “Yes, no, sorry”. Selvi was run out by half the length of the pitch and he departed staring daggers at me.

I made up my mind to stay in the middle as long as possible (a) to make up for running Selvi out and, (b) to avoid Harold who I knew would be breathing fire. Alas, the best-laid plans. A couple of overs later Lou bowled me a full toss. I thought all my Christmases had come at once. I lifted my head, hit across the line and the ball thudded into the stumps. When I got to the dressing room, Harold closed the door and gave me an unmerciful tongue lashing. He was livid and said inter alia “What is the matter with you? Not only do you run Selvi out you get out to a cock shot. You are a bloody menace.”

I didn’t say a word because he was right. I sought out Selvi, who was rightfully furious with me, and apologized. He accepted my apology and we shook hands and moved on. We lost the match and next week I entered college from a side entrance to avoid the Kadlay man and Cobra man, legendary street hawkers who had, for years, peddled their wares at the gate of the school and who were our strongest supporters and our most stringent critics.

Later in the season, I scored a century against Trinity. Centuries were pretty rare and Harold was over the moon. He grabbed me by the shoulders and, beaming like a cat who had eaten all the cream, said: “Well done Michael, terrific performance, I knew you could do it and, by the way, you are not really a bloody menace.” We had a bit of a laugh.

The RT was a battle between two equally balanced sides which on a scale of 1 to 10, would probably have been rated at 7. When stumps were drawn, we were three wickets away from victory. There were no outstanding performances, with Brendon doing best for us top-scoring with 48 and taking four wickets in the Thomian first innings

The ‘57 side, captained by Fitzroy Crozier was the strongest I played in and arguably was the strongest side in the competition that year. We had four fourth year players, three third year players, one second year player and four very talented “Freshers” in Lorenz Pereira, the Samarasinghe brothers R K and S C and Pat Poulier. We were going to give the Thomians hell, maybe we were over-confident.

Barney announced that this year would be his last year as coach. We breezed through the early matches hardly ever being put to the test.

Life was great, the only cloud in the sky was the political situation. SWRD Bandaranaike had resigned from the UNP and had formed his own party and was going to challenge the government at the next election on a policy of “Sinhala only”. I was 17 years old and politics meant nothing to me. Although, my dad was very concerned and said that the “Sinhala only” policy would be a disaster for Sri Lanka, and if Bandaranaike won the election he advised me to follow my two brothers to Australia.

I had opened the batting with Selvi for two seasons. For one and a half of those seasons, I scored faster than Selvi. That changed on the day we played St Joseph’s at Darley Rd. We won the toss and Selvi and I walked out together, nothing appeared different except that when we got to the middle Selvi cut and hooked the Josephian bowlers like there was no tomorrow. He left me for dead and made 99.

The rumour in the market place was that Selvi had a secret girlfriend to whom he used to write and on the morning of the game he had a received a “Dear Selvi” letter and decided to take his anger out on the Josephian bowlers. We played Nalanda the following week. We batted second and with Selvi still in a swashbuckling mood we put on over 50 for the first wicket, with Selvi scoring most of the runs.

I went home, had a shower, and went to give my Dad a report on the day’s play. While I was talking to him he told me he was not feeling well and, to cut the long story short, he died within the next 48 hours. His death was a devastating blow as I loved him very much. The immediate result was that the family decided to migrate to Australia as soon as possible as Bandaranaike had won the election.

About three days after my Dad’s funeral, Dudley de Silva, the Principal of Royal asked for an appointment to meet my Mum. He said that he was aware of our plans to migrate and asked if we would postpone them as he wanted me to captain in ‘57. I declined the offer because I was grieving for my father and wanted to make a fresh start in Australia as soon as possible. Also, I never had any aspirations to captain Royal. When my older brother Peter heard of my refusal he applied immense emotional pressure, saying that my Dad would have been proud to see me captain. It was emotional blackmail and I gave in after a week. In the interim Selvi completed a century against Nalanda.’

Features

Sri Lanka deploys 4,700 security personnel to protect electric fences amid human-elephant conflict

By Saman Indrajith

Sri Lanka has deployed over 4,700 Civil Security Force personnel to protect the electric fences installed to mitigate human-elephant conflict, Minister of Environment Dammika Patabendi told Parliament on Thursday.

The minister stated that from 2015 to 2024, successive governments have spent 906 million rupees (approximately 3.1 million U.S. dollars) on constructing elephant fences. During this period, 5,612 kilometers of electric fencing have been built.

He reported that between 2015 and 2024, 3,477 wild elephants and 1,190 people lost their lives due to human-elephant conflict. Electric fences remain a key measure in controlling this crisis, he added.

Between January 1 and 31, 2025, 43 elephants and three people have died as a result of such conflicts. Additionally, 21,468 properties have been damaged between 2015 and 2024, the minister noted.

Features

Electoral reform and abolishing the executive presidency

by Dr Jayampathy Wickramaratne,

President’s Counsel

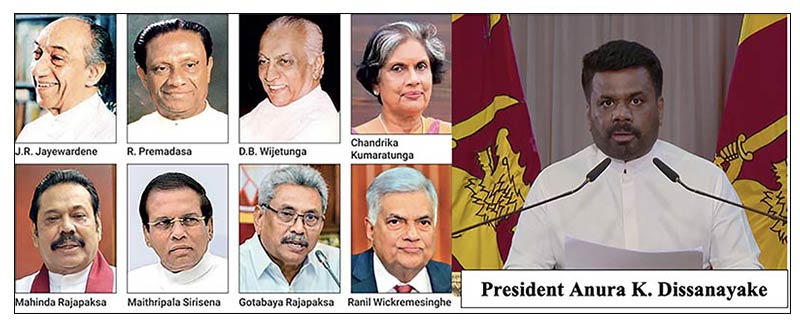

The Sri Lankan Left spearheaded the campaign against introducing the executive presidency and consistently agitated for its abolition. Abolition was a central plank of the platform of the National People’s Power (NPP) at the 2024 presidential elections and of the Janatha Vimukthi Peramuna (JVP) at all previous elections.

Issues under FPP or a mixed system

President Anura Kumara Dissanayake, participating in the ‘Satana’ programme on Sirasa TV, recently reiterated the NPP’s commitment to abolition and raised four issues related to accompanying electoral reform.

The first is that proportional representation (PR) did not, except in a few instances, give the ruling party a clear majority, resulting in a ‘weak parliament’. Therefore, electoral reform is essential when changing to a parliamentary form of government.

Secondly, ensuring that different shades of opinion and communities are proportionally represented may be challenging under the first-past-the-post system (FPP). For example, as the Muslim community in the Kurunegala district is dispersed, a Muslim-majority electorate will be impossible. Under PR, such representation is possible, as happened in 2024, with many Muslims voting for the NPP and its Muslim candidate.

The third issue is a difficulty that might arise under a mixed (FPP-PR) system. For example, the Trincomalee district returned Sinhala, Tamil and Muslim candidates at successive elections. In a mixed system, territorial constituencies would be fewer and ensuring representation would be difficult. For the unversed, there were 160 electorates that returned 168 members under FPP at the 1977 Parliamentary elections.

The fourth is that certain castes may not be represented under a new system. He cited the Galle district where some of the ‘old’ electorates had been created to facilitate such representation.

It might straightaway be said that all four issues raised by President Dissanayake have substantial validity. However, as the writer will endeavour to show, they do not present unsurmountable obstacles.

Proposals for reform, Constitutional Assembly 2016-18

Proposals made by the Steering Committee of the Constitutional Assembly of the 2015 Parliament and views of parties may be referred to.

The Committee proposed a 233-member First Chamber of Parliament elected under a Mixed-Member Proportional (MMP) system that seeks to ensure proportionality in the final allocation of seats. 140 seats (60%) will be filled by FPP. The Delimitation Commission may create dual-member constituencies and smaller constituencies to render possible the representation of communities of interest, whether racial, religious or otherwise. 93 compensatory seats (40%) will be filled to ensure proportionality. Of these, 76 will be filled by PR at the provincial level and 12 by PR at the national level, while the remaining 5 seats will go to the party that secures the highest number of votes nationally.

The Sri Lanka Freedom Party agreed with the proposals in principle, while the Joint Opposition (the precursor of the Sri Lanka Podujana Peramuna) did not make any specific proposals. The Tamil Nationalist Alliance was willing to consider any agreement between the two main parties on the main principles in the interest of reaching an acceptable consensus.

The Jathika Hela Urumaya’s position was interesting. If the presidential powers are to be reduced, the party obtaining the highest number of votes should have a majority of seats. Still, the representation of minor political parties should be assured. Therefore, the number of seats added to the winning party should be at the expense of the party placed second.

The All Ceylon Makkal Congress, Eelam People’s Democratic Party, Sri Lanka Muslim Congress and the Tamil Progressive Alliance jointly proposed that the principles of the existing PR system be retained but with elections being held for 40 to 50 electoral zones and a 2% cut-off point. The Janatha Vimukthi Peramuna was for the abolition of the executive presidency and, interestingly, suggested a mixed electoral system that ensures that the final outcome is proportional.

CDRL proposals

The Collective for Democracy and Rule of Law (CDRL), a group of professionals and academics that included the writer, made detailed proposals on constitutional reform in 2024. It proposed returning to parliamentary government. The legislature would be bicameral, with a House of Representatives of 200 members elected as follows: 130 members will be elected from territorial constituencies, including multi-member and smaller constituencies carved out to facilitate the representation of social groups of shared interest; Sixty members will be elected based on PR at a national or provincial level; Ten seats would be filled through national-level PR from among parties that failed to secure a seat through territorial constituencies or the sixty seats mentioned above, enabling small parties with significant national presence without local concentration to secure representation. Appropriate provisions shall be made to ensure adequate representation of women, youth and underrepresented interest groups.

The writer’s proposal

The people have elected the NPP leader as President and given the party a two-thirds majority in Parliament. It is, therefore, prudent to propose a system that addresses the concerns expressed by the President. Otherwise, we will be going around in circles. The writer believes that the CDRL proposals, suitably modified, present a suitable basis for further discussion.

While the people vehemently oppose any increase in the number of MPs, it would be challenging to address the President’s concerns in a smaller parliament. The writer’s proposal is, therefore, to work within a 225-member Parliament.

The writer proposes that 150 MPs be elected through FPP and 65 through national PR. 10 seats would be filled through national-level PR from among parties that have not secured a seat either through territorial constituencies or the 65 seats mentioned above. The Delimitation Commission shall apportion 150 members among the various provinces proportionally according to the number of registered voters in each province. The Commission will then divide each province into territorial constituencies that will return the number of MPs apportioned. The Commission may create smaller constituencies or multi-member constituencies to render possible the representation of social groups of shared interest.

The 65 PR seats will be proportionally distributed according to the votes received by parties nationally, without a cut-off point. The number of ‘PR MPs’ that a party gets will be apportioned among the various provinces in proportion to the votes received in the provinces. For example, if Party A is entitled to 10 PR seats and has obtained 20% of its total vote from the Central Province, it will fill 2 PR seats from candidates from that Province, and so on. Each party shall submit names of potential ‘PR MPs’ from each of the provinces where the party contests at least one constituency in the order of its preference, and seats allotted to that party in a given province are filled accordingly. The remaining 10 seats will be filled by small parties as proposed by the CDRL.

How does the proposed system address President Dissanayake’s concerns?

The President’s concern that PR will result in a weak parliament is sufficiently addressed when a majority of MPs are elected under FPP.

Before dealing with the other three issues, it must be said that voters do not always vote for candidates from their communities. A classic example is the 1965 election result in Balapitiya, a Left-oriented constituency dominated by a particular caste. The Lanka Sama Samaja Party boldly nominated L.C. de Silva, from a different caste, to contest Lakshman de Silva, a long-standing MP who crossed over to bring down the SLFP-LSSP coalition. Balapitiya voters punished Lakshman and elected L.C.

Multi-member constituencies have generally served their purpose but not always. The Batticaloa dual-member constituency had been created to ‘render possible’ the election of a Tamil and a Muslim. At the 1970 elections, the four leading candidates were Rajadurai of the Federal Party, Makan Markar of the UNP, Rahuman of the SLFP and the independent Selvanayagam. The Muslim vote was closely split between Macan Markar and Rahuman, resulting in both losing. Muslim voters surely knew that a split might deny Muslim representation but preferred to vote according to their political convictions.

The President’s second concern that a dispersed community may not get representation under FPP will also be addressed better under the proposed system. Taking the same Kurunegala district as an example, a party could attract Muslim voters by placing a Muslim high up on the PR list. Similarly, a Tamil party could place a candidate from a depressed community high up in its Northern Province PR list to attract voters of depressed communities and ensure their representation.

The third concern was that the number of electorates would be less under a mixed system, making it challenging to carve out electorates to facilitate the representation of communities, the Trincomalee district being an example. Empowering the Delimitation Commission to create smaller electorates assuages this concern. It will not be Trincomalee District but the whole Eastern Province to which a certain number of FPP MPs will be allotted, giving the Commission broad discretion to carve out electorates. The Commission could also create multimember constituencies to render possible the representation of communities of interest. The fourth concern about caste representation would also be addressed similarly.

It may be noted that the difference between the number of FPP MPs (150) under the proposed system is only 10% less than that under the delimitation of 1975 (168). Also, there will be no cut-off point for PR as against the present cut-off of 5%. This will help small as well as not-so-small parties. Reserving 10 seats for small parties also helps address the concerns of the President.

No spoilers, please. Don’t let electoral reform be an excuse for a Nokerena Wedakama

The writer submits the above proposals as a basis for discussion. While a stable government and the representation of various interests are essential, abolishing the dreaded Executive Presidency is equally important. These are not mutually exclusive.

President Dissanayake also said on Sirasa TV that once the local elections are over, the NPP would first discuss the issue internally. This is welcome as there would be a government position, which can be the basis for further discussion.

This is the first time a single political party committed to abolition has won a two-thirds majority. Another such opportunity will almost certainly not come. Let there be no spoilers from either side. Let electoral reform not be an excuse for retaining the Executive Presidency. Let the Sinhala saying ‘nokerena veda kamata konduru thel hath pattayakuth thava tikakuth onalu’ not apply to this exercise (‘for the doctoring that will never come off, seven measures and a little more, of the oil of eye-flies are required’—translation by John M. Senaveratne, Dictionary of Proverbs of the Sinhalese, 1936).

According to recent determinations of the Supreme Court, a change to a parliamentary form of government requires the People’s approval at a referendum. While the NPP has a two-thirds majority, it should not take for granted a victory at a referendum held late in the term of Parliament for, then, there is the danger of a referendum becoming a referendum on the government’s performance rather than one on the constitutional bill, with opposition parties playing spoilers. If the government wishes to have the present form of government for, say, four years, it could now move a bill for abolition with a sunset clause that provides for abolition on a specified date. Delay will undoubtedly frustrate the process and open the government to the accusation that it indulged in a ‘nokerena vedakama’.

Features

Did Rani miss manorani ?

(A film that avoids the ‘Mannerism’ of a Biopic: Rani)

by Bhagya Rajapakshe

bhagya8282@gmail.com

This is only how Manorani sees Richard. It doesn’t have a lot of what Richard did. Although Manorani is not someone who pays attention to the happenings in the country. It was only after her son was kidnapped that she began to feel that this was happening in the country.She had human emotions. But she was a person who smoked cigarettes and drank whiskey and lived a merry life.”

(Interview with “Rani” film director Ashoka Handagama by Upali Amarasinghe – 02.02.2025 ‘Anidda’ weekend newspaper, pages 15 and 19)

The above statement shows the key attitude of the director of the movie, “Rani” towards the central character of the film, Dr. Manorani Sarawanamuttu. This statement is highly controversial. Similarly, the statement given by the director to Groundviews on 30.01.2025 about capturing the depth of Rani’s character shows that he has done so superficially, frivolously?

A biopic is a specific genre of cinema. This genre presents true events in the life of a person (a biography), or a group of people who are currently alive or who belong to history with recognisable names. The biopic genre often artistically and cinematically explores keenly the main character along with a few secondary characters connected to the central figure. World cinema is proof that even if the characters are centuries old, they are carefully researched and skilled directors take care to weave the biographies into their films without causing any harm or injustice to the original character.

According to the available authentic reports, Manorani Saravanamuthu was a professionally responsible medical doctor. Chandri Peiris, a close friend of her family, in his feature article on Manorani in the ‘Daily Mirror’ newspaper on 06th November 2021, says this about her:

“She was a doctor who had her surgeries in the poorest areas around Colombo which made her popular with communities who preferred their women to be seen by female doctors. She had a wonderful manner with her patients which my mother described by saying, ‘looking at her is enough to make you well …. When it came to our outlandish group of friends, she was always there to steer many of us through some very personal issues such as: unplanned pregnancies, teenage pregnancies, mental breakdowns, STD’s, young lovers who ran away and married, depression, circumcisions, break-ups, fractures, dance injuries, laryngitis (especially among the actors and singers) fevers, pimples, and even the odd boil on the bum.”

But the image of Rani depicted by Handagama in his film is completely different from this. According to the film, a major feature of her life consisted of drinking whiskey and smoking cigarettes. Her true role is unspoken, hidden in the film. A grave question arises as to whether the director spent adequate time doing the research? to find out who Manorani really was. In his article Chandri Peiris further says the following about Manorani:

“Soon after the race riots in 1983, Manorani (along with Richard) helped a great many Sri Lankan Tamils to find refuge in countries all over the world. Nobody knew about this. But all of us who used to hang around their house kept seeing unfamiliar people come over to stay a few days and then leave. Among them were the three sons of the Master-in-Charge of Drama at S. Thomas’ College, who were swiftly sent abroad by the tireless efforts of this mother and son. It was then that we worked out that their home was a safehouse. … Manorani was vehemently opposed to the terror wreaked by the LTTE and always wanted Sri Lanka to be one country that was home to the many diverse cultures within it. When the ethnic strife developed into a full-on war with those who wanted to create a separate state for Tamil Eelam, she remained completely against it.”

According to the director of the film, if Rani had no awareness of what was happening in the country and the world, how could she have helped the victims survive and leave the country during that life-threatening period? It is clear from all this that the director has failed to fully study the character of Manorani and what she did. There is a scene where Manorani watches a Sinhala stage play with much annoyance and on her way back home with Richard, she is shown insensitively avoiding Richard’s friend Gayan being assaulted by a mob. This demeanour does not match the actual reports and information published about Manorani. How did the director miss these records? It shows his indifference to researching background information for a film such as this. He clearly does not think that research is essential for a sharp-witted artist in creating his artwork. In his own words, he told the Anidda newspaper:

“But the information related to this is in the public domain and the challenge I had was to interpret that information in the way I wanted. I am not an investigative journalist; My job is to create a work of art. That difference should be understood and made.”

And according to the director, “I was invited to do the film in 2023. The script was written within two to three months and the shooting was planned quickly.” Thus, it is clear that there has been no time to study the inner details related to Manorani, the main character of the film, or the character’s Mannerism. Professor Sarath Chandrajeewa, who published a book with two critical reviews on Handagama’s previous film ‘Alborada’, emphasises in both, that ‘Alborada’ also became weak due to the lack of proper research work’ (Lamentation of the Dawn (2022), pages 46-57).

Directors working in the biopic genre with a degree of seriousness consider it their responsibility to study deeply and construct the ‘mannerism’ of such central characters to create a superior biographical film. For example, in Kabir Khan’s 2021 film ’83’ the actor Tahir Raj Bhasin, who played the role of Sunil Gavaskar, said that it took him six months to study Sunil Gavaskar’s unique style characteristics or Mannerism.

Also, Austin Butler, the actor who played the role of Elvis Presley in the movie ‘Elvis’ directed by Buz Luhrmann and released in 2022, said in a news conference: After he started studying the character of Elvis, he became obsessed with the character, without meeting or talking to his family for nearly one year, while making the film in Australia before, during Covid and after.

‘Oppenheimer’ (2023) was written and directed by Christopher Nolan, in which Cillian Murphy plays the role of Oppenheimer. Nolan read and studied the 700-page story about Oppenheimer called ‘American Prometheus’ . It is said that it took three months to write the script and 57 days for shooting, and finally a two-hour film was created. The rejection of such intense studies by our filmmakers will determine the future of cinema in this country.

Acting is the prime aspect of a movie. The character of Manorani is performed very skillfully in the movie. But certain of her characteristics and mannerism become repetitive and in their very repetitiveness become tiresome to watch. For example, right across the film Manorani is shown smoking, drinking alcohol, sitting and thinking, going towards a window and thinking and smoking again. It would have been better if it had been edited. The audience is thereby given the impression that Manorani lives on cigarettes and whiskey. Although smoking and drinking alcohol is a common practice among some women of Manorani’s social class, it is depicted in the film so repetitively that it creates a sense of revulsion in the viewer. In the absence of close-ups and a play of light and dark, Manorani’s mental states cannot be seen in their intense three dimensionality. It is a question whether the director gave up directing and let the actress play the role of Manorani as she wished. At the beginning of the film, close-ups of Manorani appear with the titles but gradually become normal camera angles in the film. This avoids the use of close-ups of Manorani’s face to show emotion in the most shocking moments in the film. Below are some films that demonstrate this cinematic technique well.

‘Three Colours: Blue’ (1993) French, Directed by Kryzysztof Kies’lowski.

‘Memories in March’

(2010) Indian, Directed by Sanjoy Nag.

‘Manchester by the Sea’

(2016) English, Directed by Keneth Lonergan.

‘Collateral Beauty’

2016) English, Directed by David Frankel.

Certain characters appear in the film without any contribution to building Manorani’s role. Certain scenes such as the Television news, bomb explosions, dialogue scenes where certain characters interview Manorani are not integrated into the film’s narrative and feel forced. The scene with the group of hooligans in a jeep at the end of the film is like a strange tail to the film.

Richard’s sexual orientation, which is hinted at the end of the film by these thugs in the final scene, is an insult to him. It is a great disrespect to those characters to present facts without strong information analysis and to tell the inner life of those characters while presenting a real character through an artwork with real names. The director should not have done such humour and humiliation.

There is some thrill in seeing actors who resemble the main political personalities of that era playing those roles in the film. In this the film has more of a documentary than a fictional quality but it barely marks the socio-political history of this country during the period of terror in 88-89. The character of Manorani was created as a person floating in that history ungrounded, without a sense of gravity.

The film’s music and vocals are mesmerising. But unfortunately, the song ‘Puthune’ (Dearest Son), which has a very strong lyrical composition, melody and singing, is placed at the end of the film, so the audience does not know its strength. This is because the audience starts to leave the cinema as soon as the song starts, when the closing credits scrolled down. If the song had accompanied the scene on the beach where we see Manorani for the last time, the audience would have felt its strength.

Manorani’s true personality was a unique blend of charm, sensitivity, compassion, intelligence, warmth and fun, which enhanced her overall beauty, as evidenced by various written accounts of her. Art critics and historians H. W. Johnson and Anthony F. A Johnson state in their book ‘History of Art’ (2001), “Every work of art tells whether it is artistic or not. And the grammar and structure of the form will signal to us that.”

-

Business5 days ago

Business5 days agoSri Lanka’s 1st Culinary Studio opened by The Hungryislander

-

Sports6 days ago

Sports6 days agoHow Sri Lanka fumbled their Champions Trophy spot

-

Features6 days ago

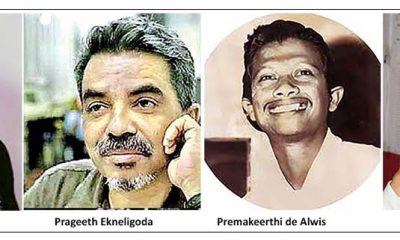

Features6 days agoThe Murder of a Journalist

-

Sports6 days ago

Sports6 days agoMahinda earn long awaited Tier ‘A’ promotion

-

Features6 days ago

Features6 days agoExcellent Budget by AKD, NPP Inexperience is the Government’s Enemy

-

Sports5 days ago

Sports5 days agoAir Force Rugby on the path to its glorious past

-

News6 days ago

News6 days agoSri Lanka’s first ever “Water Battery”

-

Features5 days ago

Features5 days agoRani’s struggle and plight of many mothers