Features

Role of scientists, professionals and intellectuals in guiding nation’s destiny

(Address delivered by Chairman, National Science Foundation, Prof. Ranjith Senaratne, at the CVCD Awards ceremony, held at the BMICH, on 01 July, 2022. He was the Chief Guest at the event)

I consider it a singular honour to have been invited to address this august assembly where outstanding academics are recognised for their remarkable accomplishments in S&T and allied fields. It is, indeed, rare to see such a galaxy of high-profile, luminous personalities, including the Secretary to the Ministry of Education, the Chairman of the UGC, Vice-Chancellors, brilliant academics of exceptional performance, and other luminaries, under one roof, and I express my deep appreciation to the Chairperson, and members of the CVCD (Committee of Vice-Chancellors and Directors) for the rare opportunity afforded to me.

Former British Prime Minister Benjamin Disraeli said that a university is a place of light, liberty and learning; however, it can remain so only as long as its staff can claim a place on the frontiers of knowledge, and continue to take part in moving their country forward, through their scholarly pursuits. Besides being the fountainheads of new knowledge, the universities should also be pinnacles of culture, crucibles for R&D, habitats for innovation and invention, and seedbeds, of novel enterprises. The recognition of a university depends principally on the quality of their staff – that is, how well recognized they are in their respective fields, at home and abroad, how well their work is received in the outside world, and the quality of their contribution to the community, and to the society, at large.

As you are aware, there are 17 universities, and seven postgraduate institutes, within the purview of the UGC, which are endowed with over 6,500 academics, including over 1,000 professors and associate professors, about 2,500 senior lecturers, and around 75,000 undergraduates, who are the distilled spirit, the cream of the cream of the youth of our country. The universities, ─ as knowledge-producing and knowledge-disseminating institutions, producers of human capital and wealth creators – can and should play a pivotal role in the development of our nation.

When we look at the intellectual landscape of our universities, we see a range of “mountains”, that have silently, unobtrusively and selflessly contributed greatly to the noble task of nation building. The nation, and the society, unfortunately, are only poorly aware of their worth, and they remain the unsung academic heroes of our country. However, they persist with fulfilling their obligation to the nation, even under most trying circumstances, because of their relentless passion for intellectual work and scholarly pursuits, and their love and affection for the motherland.

Dear CVCD award winners, you are the heart and soul of the university sector. You are the gems and jewels in the crown of Sarasavi Matha and the most treasured resource of our university system. You have set benchmarks of excellence and new standards for our academic community and the country. Your passion and perseverance have inspired us all. We take great pride in your dedication and devotion to excellence. I am certain that Sarasavi Matha is elated and proud of your remarkable accomplishments, and that she is shedding tears of joy on this occasion and would crave many more sons and daughters of your calibre and stature. I salute you for your outstanding achievements and invaluable contributions in your respective fields. I congratulate each of you from the bottom of my heart.

Dear Award Winners, we should very much like to see your academic dynamism and intellectual vibrancy becoming contagious, thereby infecting more and more staff who will acquire and internalize your qualities and attributes to attain excellence in education, research, and service to the community.

Thomas Alva Edison said: “Genius is 1% inspiration and 99% perspiration.” Edison was hard of hearing, since his early teens, and attended school for only for a few months and was taught at home by his mother. This curious and creative child later invented the phonograph and the gramophone, the light bulb, and the motion picture camera, and had more than 1,000 patents to his credit. Edison personified perseverance – the capacity to stand up again and again after every fall, and to keep moving forward. Samuel Johnson said, “Great works are performed not by strength, but by perseverance.” Newton said, “If I have seen farther than others, it is because I have stood on the shoulders of giants.” We need to learn from these geniuses. We know that there is no shortcut to distinction or excellence. We also know that diamonds are only coal put under immense pressure.

The intellectual prowess and creative power of Sri Lankans are not second to those of any other people in the world. There are children and young scientists, amongst us, who can be another Stephen Hawking or Edison. But it is incumbent upon us to create and sustain a nurturing, stimulating and conducive environment so that they will fully blossom and express their innate and inborn potential to the benefit of self, community and humanity at large. We need to make our universities crucibles where ordinary talent is transformed into extraordinary talent and extraordinary talent into genius. It is our cherished dream to see more and more imposing Sri Lankan mountains emerge on the global intellectual landscape. We hope that this awards scheme will make a tangible contribution towards that end.

We are well aware that our country is going through a crisis, unprecedented in our history, since independence, with far-reaching economic and social implications. As academics, scientists, administrators and professionals, in senior positions in academia and public sector institutions, whose education has been supported by the community, we have a moral obligation and an inescapable responsibility to contribute our might to overcome the crisis and rebuild the economy.

The late Christoper Weeramantry, former Vice-President of the International Court of Justice, The Hague, Netherlands and Emeritus Professor of Law at the Monash University, Australia, identified four key functions of an intellectual:

The continuing acquisition and systematization of knowledge

The advancement of knowledge

The communication of knowledge

Advice and guidance based upon knowledge.

Many of our scientists fulfill the first three, but hardly meet the fourth one. This is one reason why Sri Lanka still remains as a developing country despite its high literacy rate, high human development index, rich natural endowments and strategic location. Georges Clemenceau, Prime Minister of France during the World War I, said, “War is too important a matter to be left to the Generals”. I could say without fear of contradiction that “Development is even more a matter to be left entirely to politicians”. Therefore, the scientists, professionals and intellectuals of the country should weld themselves into a cohesive and vibrant force to serve as a guiding star and navigate the destiny of our nation to usher in a better tomorrow for our people and posterity.

As most of the key movers and shakers of the higher education sectors of our country, including the Secretary of Education, the Chairman of the UGC, Vice-Chancellors and a cross section of the accomplished academics, are present on this occasion, I wish to seize this opportunity to share some of my thoughts at this crucial juncture for your kind reflection and intervention.

Today, technology is the prime driver of and the key to economic development and universities contribute over 60% of the R&D personnel in the country, thus they become the brains trust and intellectual pulse of the nation. With well-equipped laboratories, well-stocked libraries and good IT infrastructure facilities, they also constitute the backbone of a knowledge economy. However, the weak link between academia and R&D institutions, in our country, poses a constraint to sharing of human and physical resources across institutional boundaries. Such inter-institutional collaboration, besides producing synergy and complementarity, will facilitate rationalization of high-end equipment and minimize duplication of expensive equipment and their downtime.

Presently, universities and many R&D institutions come within the purview of the Ministry of Education and its Secretary, Mr. Ranasinghe, is already acting to bring together all compartmentalized and insulated R&D institutions, in the Ministry, onto one platform and thereby promote effective use and sharing of their human, physical and financial assets for national development. We very much welcome and appreciate this strategic move.

The NSF, in keeping with its mandate, has set up two digital bases, namely the Global Digital Platform and high-end analytical, research and testing instrument database. The former is aimed at harnessing high-profile Sri Lankan expatriates for national development, with a special focus on the higher education and R&D sectors, while the latter, at providing reliable analytical and testing services and research support to academia, R&D institutions, and industry; this will obviate the duplication of high-end equipment, and facilitate and promote public-private partnerships and research by universities and institutions, particularly those lacking the requisite analytical facilities and competencies. However, there is still much room for expanding the two databases to administer a turbo boost to research and innovation in the country. It is imperative to unify the relevant institutions into one ecosystem in order to derive potential benefits from them. In this connection, forging a strategic tri-partite partnership between the UGC, CVCD and NSF will be mutually rewarding and reinforcing, and leading to a win-win situation for all. I am certain that this will receive due attention of the Chairman of the UGC, Prof. Sampath Amaratunga, who is a champion in bringing down walls and building strategic bridges, partnerships and networks to enhance the higher education sector of the country.

It is valuable to set goals in life. I think it will be even more valuable to set goals that are seemingly unattainable. Michelangelo said, “The greatest danger for most of us is not that our aim is too high and we miss it, but that it is too low and we reach it”. It is, therefore, important to set lofty goals and work with perseverance, persistence and perspiration (the 3Ps) to attain them. Confucius said, “By nature, people are similar, through nurture, they become distinct”. As mentioned before, the IQ, EQ or CQ (Creativity Quotient) of Sri Lankans are second to none in the world and despite many constraints and challenges, 25 Sri Lankan scientists have reached the top 2% in the world, and with a conducive and enabling environment they could easily reach the top 1% cohort. Hong Kong-based scientists Kwok-Yung Yuen and Sri Lanka’s Joseph Sriyal Malik Peiris won the prize in life sciences in the 2021 Future Science Prize dubbed “China Nobel Prize” for their major discoveries of SAR-CoV-1 as the causative agent of the global SARS outbreak in 2003 with impact on combating COVID-19 and emerging infectious diseases. With an imposing cultural heritage and rich civilization, our aim should be to produce Nobel Laureates from Sri Lanka before 2050.

The NSF, being a hub institution, it is only too happy to go the extra mile to mobilize and channel the requisite high-profile Sri Lankan expatriate scientists, technologists and professionals across the globe to build strategic world-class multidisciplinary research teams in Sri Lanka so as to promote cutting edge research. This would lead to wealth creation through innovation and even to the production of Nobel Laureates in the long run.

The present CVCD Chairperson, Prof. Nilanthi de Silva, is a world-class scientist in the top 2%; she’s also an institution builder. I am confident that her able and visionary leadership will afford a new direction and dimension to the CVCD, making it a robust guiding force and a potent catalyst of the higher education sector of the country, propelling it to greater heights. I wish her and the members of the CVCD all the success in their endeavours to advance the cause of higher education in Sri Lanka. Thank you.

Features

Crucial test for religious and ethnic harmony in Bangladesh

Will the Bangladesh parliamentary election bring into being a government that will ensure ethnic and religious harmony in the country? This is the poser on the lips of peace-loving sections in Bangladesh and a principal concern of those outside who mean the country well.

Will the Bangladesh parliamentary election bring into being a government that will ensure ethnic and religious harmony in the country? This is the poser on the lips of peace-loving sections in Bangladesh and a principal concern of those outside who mean the country well.

The apprehensions are mainly on the part of religious and ethnic minorities. The parliamentary poll of February 12th is expected to bring into existence a government headed by the Bangladesh Nationalist Party (BNP) and the Islamist oriented Jamaat-e-Islami party and this is where the rub is. If these parties win, will it be a case of Bangladesh sliding in the direction of a theocracy or a state where majoritarian chauvinism thrives?

Chief of the Jamaat, Shafiqur Rahman, who was interviewed by sections of the international media recently said that there is no need for minority groups in Bangladesh to have the above fears. He assured, essentially, that the state that will come into being will be equable and inclusive. May it be so, is likely to be the wish of those who cherish a tension-free Bangladesh.

The party that could have posed a challenge to the above parties, the Awami League Party of former Prime Minister Hasina Wased, is out of the running on account of a suspension that was imposed on it by the authorities and the mentioned majoritarian-oriented parties are expected to have it easy at the polls.

A positive that has emerged against the backdrop of the poll is that most ordinary people in Bangladesh, be they Muslim or Hindu, are for communal and religious harmony and it is hoped that this sentiment will strongly prevail, going ahead. Interestingly, most of them were of the view, when interviewed, that it was the politicians who sowed the seeds of discord in the country and this viewpoint is widely shared by publics all over the region in respect of the politicians of their countries.

Some sections of the Jamaat party were of the view that matters with regard to the orientation of governance are best left to the incoming parliament to decide on but such opinions will be cold comfort for minority groups. If the parliamentary majority comes to consist of hard line Islamists, for instance, there is nothing to prevent the country from going in for theocratic governance. Consequently, minority group fears over their safety and protection cannot be prevented from spreading.

Therefore, we come back to the question of just and fair governance and whether Bangladesh’s future rulers could ensure these essential conditions of democratic rule. The latter, it is hoped, will be sufficiently perceptive to ascertain that a Bangladesh rife with religious and ethnic tensions, and therefore unstable, would not be in the interests of Bangladesh and those of the region’s countries.

Unfortunately, politicians region-wide fall for the lure of ethnic, religious and linguistic chauvinism. This happens even in the case of politicians who claim to be democratic in orientation. This fate even befell Bangladesh’s Awami League Party, which claims to be democratic and socialist in general outlook.

We have it on the authority of Taslima Nasrin in her ground-breaking novel, ‘Lajja’, that the Awami Party was not of any substantial help to Bangladesh’s Hindus, for example, when violence was unleashed on them by sections of the majority community. In fact some elements in the Awami Party were found to be siding with the Hindus’ murderous persecutors. Such are the temptations of hard line majoritarianism.

In Sri Lanka’s past numerous have been the occasions when even self-professed Leftists and their parties have conveniently fallen in line with Southern nationalist groups with self-interest in mind. The present NPP government in Sri Lanka has been waxing lyrical about fostering national reconciliation and harmony but it is yet to prove its worthiness on this score in practice. The NPP government remains untested material.

As a first step towards national reconciliation it is hoped that Sri Lanka’s present rulers would learn the Tamil language and address the people of the North and East of the country in Tamil and not Sinhala, which most Tamil-speaking people do not understand. We earnestly await official language reforms which afford to Tamil the dignity it deserves.

An acid test awaits Bangladesh as well on the nation-building front. Not only must all forms of chauvinism be shunned by the incoming rulers but a secular, truly democratic Bangladesh awaits being licked into shape. All identity barriers among people need to be abolished and it is this process that is referred to as nation-building.

On the foreign policy frontier, a task of foremost importance for Bangladesh is the need to build bridges of amity with India. If pragmatism is to rule the roost in foreign policy formulation, Bangladesh would place priority to the overcoming of this challenge. The repatriation to Bangladesh of ex-Prime Minister Hasina could emerge as a steep hurdle to bilateral accord but sagacious diplomacy must be used by Bangladesh to get over the problem.

A reply to N.A. de S. Amaratunga

A response has been penned by N.A. de S. Amaratunga (please see p5 of ‘The Island’ of February 6th) to a previous column by me on ‘ India shaping-up as a Swing State’, published in this newspaper on January 29th , but I remain firmly convinced that India remains a foremost democracy and a Swing State in the making.

If the countries of South Asia are to effectively manage ‘murderous terrorism’, particularly of the separatist kind, then they would do well to adopt to the best of their ability a system of government that provides for power decentralization from the centre to the provinces or periphery, as the case may be. This system has stood India in good stead and ought to prove effective in all other states that have fears of disintegration.

Moreover, power decentralization ensures that all communities within a country enjoy some self-governing rights within an overall unitary governance framework. Such power-sharing is a hallmark of democratic governance.

Features

Celebrating Valentine’s Day …

Valentine’s Day is all about celebrating love, romance, and affection, and this is how some of our well-known personalities plan to celebrate Valentine’s Day – 14th February:

Valentine’s Day is all about celebrating love, romance, and affection, and this is how some of our well-known personalities plan to celebrate Valentine’s Day – 14th February:

Merlina Fernando (Singer)

Yes, it’s a special day for lovers all over the world and it’s even more special to me because 14th February is the birthday of my husband Suresh, who’s the lead guitarist of my band Mission.

We have planned to celebrate Valentine’s Day and his Birthday together and it will be a wonderful night as always.

We will be having our fans and close friends, on that night, with their loved ones at Highso – City Max hotel Dubai, from 9.00 pm onwards.

Lorensz Francke (Elvis Tribute Artiste)

On Valentine’s Day I will be performing a live concert at a Wealthy Senior Home for Men and Women, and their families will be attending, as well.

I will be performing live with romantic, iconic love songs and my song list would include ‘Can’t Help falling in Love’, ‘Love Me Tender’, ‘Burning Love’, ‘Are You Lonesome Tonight’, ‘The Wonder of You’ and ‘’It’s Now or Never’ to name a few.

To make Valentine’s Day extra special I will give the Home folks red satin scarfs.

Emma Shanaya (Singer)

I plan on spending the day of love with my girls, especially my best friend. I don’t have a romantic Valentine this year but I am thrilled to spend it with the girl that loves me through and through. I’ll be in Colombo and look forward to go to a cute cafe and spend some quality time with my childhood best friend Zulha.

JAYASRI

Emma-and-Maneeka

This Valentine’s Day the band JAYASRI we will be really busy; in the morning we will be landing in Sri Lanka, after our Oman Tour; then in the afternoon we are invited as Chief Guests at our Maris Stella College Sports Meet, Negombo, and late night we will be with LineOne band live in Karandeniya Open Air Down South. Everywhere we will be sharing LOVE with the mass crowds.

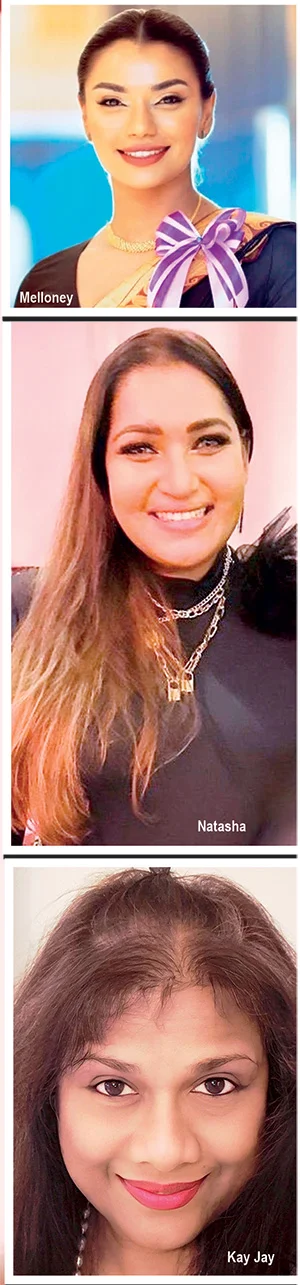

Kay Jay (Singer)

I will stay at home and cook a lovely meal for lunch, watch some movies, together with Sanjaya, and, maybe we go out for dinner and have a lovely time. Come to think of it, every day is Valentine’s Day for me with Sanjaya Alles.

Maneka Liyanage (Beauty Tips)

On this special day, I celebrate love by spending meaningful time with the people I cherish. I prepare food with love and share meals together, because food made with love brings hearts closer. I enjoy my leisure time with them — talking, laughing, sharing stories, understanding each other, and creating beautiful memories. My wish for this Valentine’s Day is a world without fighting — a world where we love one another like our own beloved, where we do not hurt others, even through a single word or action. Let us choose kindness, patience, and understanding in everything we do.

Janaka Palapathwala (Singer)

Janaka

Valentine’s Day should not be the only day we speak about love.

From the moment we are born into this world, we seek love, first through the very drop of our mother’s milk, then through the boundless care of our Mother and Father, and the embrace of family.

Love is everywhere. All living beings, even plants, respond in affection when they are loved.

As we grow, we learn to love, and to be loved. One day, that love inspires us to build a new family of our own.

Love has no beginning and no end. It flows through every stage of life, timeless, endless, and eternal.

Natasha Rathnayake (Singer)

We don’t have any special plans for Valentine’s Day. When you’ve been in love with the same person for over 25 years, you realise that love isn’t a performance reserved for one calendar date. My husband and I have never been big on public displays, or grand gestures, on 14th February. Our love is expressed quietly and consistently, in ordinary, uncelebrated moments.

With time, you learn that love isn’t about proving anything to the world or buying into a commercialised idea of romance—flowers that wilt, sweets that spike blood sugar, and gifts that impress briefly but add little real value. In today’s society, marketing often pushes the idea that love is proven by how much money you spend, and that buying things is treated as a sign of commitment.

Real love doesn’t need reminders or price tags. It lives in showing up every day, choosing each other on unromantic days, and nurturing the relationship intentionally and without an audience.

This isn’t a judgment on those who enjoy celebrating Valentine’s Day. It’s simply a personal choice.

Melloney Dassanayake (Miss Universe Sri Lanka 2024)

I truly believe it’s beautiful to have a day specially dedicated to love. But, for me, Valentine’s Day goes far beyond romantic love alone. It celebrates every form of love we hold close to our hearts: the love for family, friends, and that one special person who makes life brighter. While 14th February gives us a moment to pause and celebrate, I always remind myself that love should never be limited to just one day. Every single day should feel like Valentine’s Day – constant reminder to the people we love that they are never alone, that they are valued, and that they matter.

I truly believe it’s beautiful to have a day specially dedicated to love. But, for me, Valentine’s Day goes far beyond romantic love alone. It celebrates every form of love we hold close to our hearts: the love for family, friends, and that one special person who makes life brighter. While 14th February gives us a moment to pause and celebrate, I always remind myself that love should never be limited to just one day. Every single day should feel like Valentine’s Day – constant reminder to the people we love that they are never alone, that they are valued, and that they matter.

I’m incredibly blessed because, for me, every day feels like Valentine’s Day. My special person makes sure of that through the smallest gestures, the quiet moments, and the simple reminders that love lives in the details. He shows me that it’s the little things that count, and that love doesn’t need grand stages to feel extraordinary. This Valentine’s Day, perfection would be something intimate and meaningful: a cozy picnic in our home garden, surrounded by nature, laughter, and warmth, followed by an abstract drawing session where we let our creativity flow freely. To me, that’s what love is – simple, soulful, expressive, and deeply personal. When love is real, every ordinary moment becomes magical.

Noshin De Silva (Actress)

Valentine’s Day is one of my favourite holidays! I love the décor, the hearts everywhere, the pinks and reds, heart-shaped chocolates, and roses all around. But honestly, I believe every day can be Valentine’s Day.

It doesn’t have to be just about romantic love. It’s a chance to celebrate love in all its forms with friends, family, or even by taking a little time for yourself.

Whether you’re spending the day with someone special or enjoying your own company, it’s a reminder to appreciate meaningful connections, show kindness, and lead with love every day.

And yes, I’m fully on theme this year with heart nail art and heart mehendi design!

Wishing everyone a very happy Valentine’s Day, but, remember, love yourself first, and don’t forget to treat yourself.

Sending my love to all of you.

Features

Banana and Aloe Vera

To create a powerful, natural, and hydrating beauty mask that soothes inflammation, fights acne, and boosts skin radiance, mix a mashed banana with fresh aloe vera gel.

To create a powerful, natural, and hydrating beauty mask that soothes inflammation, fights acne, and boosts skin radiance, mix a mashed banana with fresh aloe vera gel.

This nutrient-rich blend acts as an antioxidant-packed anti-ageing treatment that also doubles as a nourishing, shiny hair mask.

* Face Masks for Glowing Skin:

Mix 01 ripe banana with 01 tablespoon of fresh aloe vera gel and apply this mixture to the face. Massage for a few minutes, leave for 15-20 minutes, and then rinse off for a glowing complexion.

* Acne and Soothing Mask:

Mix 01 tablespoon of fresh aloe vera gel with 1/2 a mashed banana and 01 teaspoon of honey. Apply this mixture to clean skin to calm inflammation, reduce redness, and hydrate dry, sensitive skin. Leave for 15-20 minutes, and rinse with warm water.

* Hair Treatment for Shine:

Mix 01 fresh ripe banana with 03 tablespoons of fresh aloe vera gel and 01 teaspoon of honey. Apply from scalp to ends, massage for 10-15 minutes and then let it dry for maximum absorption. Rinse thoroughly with cool water for soft, shiny, and frizz-free hair.

-

Features5 days ago

Features5 days agoMy experience in turning around the Merchant Bank of Sri Lanka (MBSL) – Episode 3

-

Business6 days ago

Business6 days agoZone24x7 enters 2026 with strong momentum, reinforcing its role as an enterprise AI and automation partner

-

Business5 days ago

Business5 days agoRemotely conducted Business Forum in Paris attracts reputed French companies

-

Business5 days ago

Business5 days agoFour runs, a thousand dreams: How a small-town school bowled its way into the record books

-

Business5 days ago

Business5 days agoComBank and Hayleys Mobility redefine sustainable mobility with flexible leasing solutions

-

Business2 days ago

Business2 days agoAutodoc 360 relocates to reinforce commitment to premium auto care

-

Business6 days ago

Business6 days agoHNB recognized among Top 10 Best Employers of 2025 at the EFC National Best Employer Awards

-

Midweek Review2 days ago

Midweek Review2 days agoA question of national pride