Features

STUDIES, EXAMS, STRIKES & TERRORISM IN THE UK

CONFESSIONS OF A GLOBAL GYPSY

By Dr. Chandana (Chandi) Jayawardena DPhil

President – Chandi J. Associates Inc. Consulting, Canada

Founder & Administrator – Global Hospitality Forum

chandij@sympatico.ca

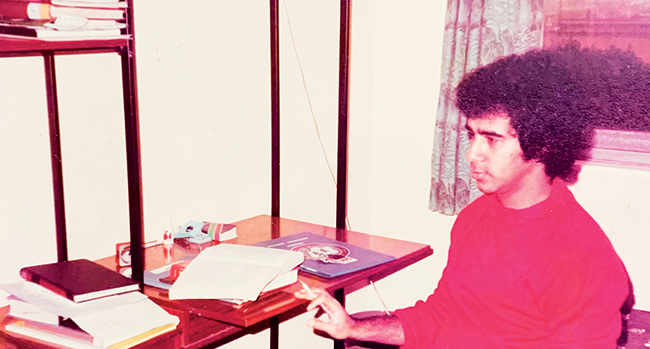

Study Strategies

“Read these eight books on Hotel Management Accounting and Corporate Finance, cover to cover.” Professor Richard Kotas gave this direction to the graduate students in the M.Sc. program in International Hotel Management, at the University of Surrey (UoS), in the United Kingdom (UK). After the 1983 autumn semester mid-term tests, other professors followed suit with similar directions for their courses in Marketing Principles for Hotel Management, International Hotel Management Seminars, Quantitative Methods, Project Design and Analysis, Computer Applications, Organization Theory and Manpower Management etc. It was overwhelming! I quickly realised that I needed to develop a practical and effective strategy for my studies.

Some of my younger batchmates who were yet to gain any management experience, followed “reading cover to cover” directions literally. To me it did not sound doable. One marketing text book had over 700 pages! As none of my batch mates worked part-time, like I did, they all had more time for studies than I. So I settled for reading only the chapter summaries and figures and tables within book chapters.In order to acquire other shortcuts, I attended some non-mandatory ‘student success strategy’ sessions. These sessions provided some excellent study and exam strategies but were not well-attended. I immediately implemented the strategies I liked. Most of them worked well for me.

Exam Strategies

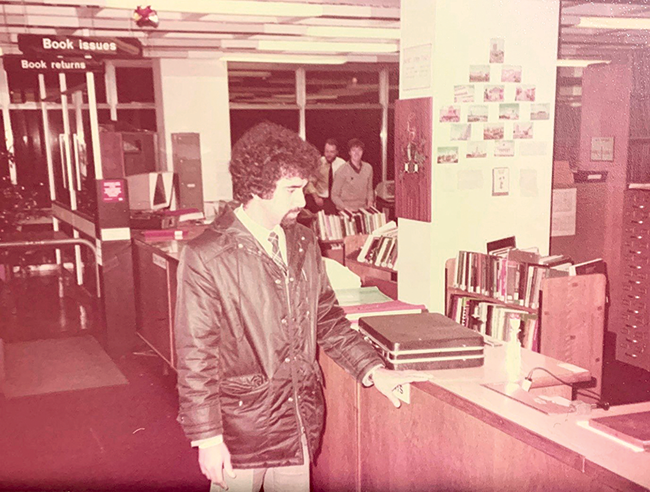

I spent a considerable amount of time at the university library analysing all old exam papers for some general courses in M.Sc. in Tourism Planning and Development, set by the same professors. I identified questions they repeated every year, in alternate years and occasionally. Based on that research, I guessed what questions could be included in the exams that I would sit.

After that I organized a M.Sc. study group of four like-minded students and assigned the most likely four questions, based on one question per graduate student basis. Each of us then became the expert on one question area per course. As the next step, we presented the answers developed by each expert, to each other. Then we debated and fine-tuned the four answers, which all four shared.

For our challenging courses such as Quantitative Methods, we made an appointment to meet each professor for a discussion. “Dr. Wanhill, the four of us are very nervous about your exam. We studied a lot and prepared some model answers to potential questions, but we still are not sure if we have done this well enough”, I told the senior lecturer who was teaching us Quantitative Methods.

Dr. Wanhill, a nice gentleman, was so impressed with our efforts that he said, “Come on chaps, don’t be nervous. Let’s go through all of your questions and answers.” He spent two hours coaching us and we guessed that the questions he spent more time in explaining were ‘sure exam questions’. This strategy helped us and four of us did well in the Quantitative Methods exams. It had been our worst course!

Implementing a tip from a ‘student success strategy’ session, I also spent time with each professor, prior to the final exam, inquiring what would be an ideal format for answering their questions at the exam. Some preferred essay type, a few liked point-form, and only one liked the idea of examples from my own career. I wrote the exams exactly the way they preferred, changing my style of answering to suit each professor. Applying my concept of ‘Personality Analysis’ and adjusting the way I communicated with each professor, proved to be beneficial.

I also learnt to invest about 30 minutes planning my answers at the beginning of each paper. I then planned to keep the last 30 minutes to review my four answers and fine-tune those before handing over my exam answer script at the last minute. With this strategy, I spent exactly 30-minutes per answer. To me, the answer plan and the time management were key elements for exam success.

After some debates about the effectiveness of ‘last minute studying’ prior to exams, I opted to adopt a concept of being at each day’s exam, right at the peak of my day. For this strategy, we first identified the number of hours each student can work without being tired. Most students were eight-hour people and a few were ten or twelve-hour people. Considering my multi-tasking work pattern in the previous years, I identified myself as a sixteen-hour person, which was rare. This meant that when the middle of an exam time was 10:00 am, I commenced my final revision studies on the same day of the exam, eight hours before that – at 2:00 am. As, at that time, I needed a maximum six hours of sleep to function well, I went to bed at 8:00 pm. This worked well for me.

When I sat one exam invigilated by Professor Richard Kotas, I could not believe my eyes. All four questions that my study group predicted were there. I had studied thoroughly the four model answers during the previous six hours since 2:00 am. “Chandi, why are you seated smiling, without answering the questions?” a baffled Professor Kotas asked me. “Sir, I am just planning my answers to these very difficult and unpredictable questions” I told him while trying to look worried. Although exam positions were not publicly announced, Professor Kotas indicated to me privately that I was overall first in both autumn and winter semester exams, something I had never achieved in my life prior to that.

Fight for Dissertation Topic

By early 1984, we began identifying topics for our dissertations, which had to be done ideally within a minimum of six months by students who had passed 10 exams over two semesters. Nine professors were assigned to supervise the nine students who were in my M.Sc. batch. When we commenced our one-on-one meetings with potential dissertation supervisors, we felt some pressure to align student dissertation topics with supervisors’ current research interests and publications.

The Head of the Department of the Hotel, Catering and Tourism Management at UoS at that time was Professor Brian Archer. He was an economist and an expert on tourism forecasting. “Ah, Chandi, I would like to suggest a dissertation topic ideal for someone like you. How about ‘Long-term tourism forecasting of South Asia?’ You can test exciting models, including mine, and even develop a new model!”, he suggested with a big and convincing smile. I simply hated that topic and had no interest in it.

I preferred to do research on a topic that would help the next stage of my career. After completing the M.Sc. program, I wanted to become the Food & Beverage Manager of a large, international five-star hotel. “I am thinking of something like, ‘Food and beverage management of British five-star hotels’ I announced to the dissatisfaction of Professor Archer. “That does not sound academically suitable for a master’s degree dissertation”, he said. I disagreed. When the university realized that I was determined to research and write on a practical subject, I was asked to make a convincing proposal to justify the suitability of my topic.

Although Professor Archer was disappointed with me on that occasion, he later became a good friend of mine. When I was the General Manager of the Lodge and the Village, Habarana, he stayed with me. He was a good chess player, and we played several games there. In later years, when he heard that I wish to do a Ph.D., he arranged an interview for me to be considered for a post of Lecturer at UoS, during my Ph.D. research. Unfortunately, as another professor in the selection committee did not support me with the same enthusiasm as Professor Archer, I did not get that job, but I re-joined UoS to do a M.Phil./Ph.D. in 1990.

After more negotiations in 1984, and revisions to my M.Sc. dissertation proposal, eventually, UoS approved a slightly modified topic for my research – ‘Food and beverage operations in the context of five-star London hotels’. Professor Richard Kotas became my dissertation supervisor. “Chandi, covering the whole of UK will be too much. Just focus on the 16 five-star hotels in London”, he suggested. I agreed and said that, “I will work or observe in all of these 16 hotels and interview the relevant managers. Kindly give me letters of introduction.” “Chandi, in addition, as the first step, you must read all books – cover to cover, and journal articles ever written in English about Food and beverage management and operations”, he suggested. I said, “Yes, Sir!” and did exactly that over a period of three months.

British Strikes

UK had strong unions and a culture of strikes. Some strikes affected me personally. One I remember clearly was towards the end of March in 1984, when the transport workers paralyzed London’s buses and subways. That strike was the first of a series of work stoppages in major British cities to protest Prime Minister, Margaret Thatcher’s proposals for local government changes. Cars and cyclists jammed roads in London as some 2.5 million people found alternate ways to work. Thousands walked while others jogged or hitch-hiked. My wife and I stayed at home without going to work.

On March 6, 1984, when I saw on the BBC TV news about a miners’ strike, I assumed that it was one of those strikes in UK which would last for a short period of time before a settlement. I was wrong. It was a major, industrial action within the British coal industry in an attempt to prevent colliery closures, suggested by the government for economic reasons. The strike was led by Arthur Scargill, the President of the National Union of Mineworkers (NUM) against the National Coal Board (NCB), a government agency. Opposition to the strike was led by the Conservative government of Margaret Thatcher that wanted to reduce the power of the trade unions. This strike lasted a year, and I eagerly waited to watch the TV news about it every evening until the strike finally ended in March, 1985.

Violent confrontations between flying pickets and police characterised the year-long strike which ended in a decisive victory for the Conservative government and allowed the closure of most of Britain’s collieries.

Many observers regarded this landmark strike as the most bitter industrial dispute in British history. The number of person-days of work lost to the strike was over 26 million, making it one of the biggest strikes in history. Thousands were arrested and charged, over a 100 were injured, and sadly, six lost their lives.

From that historic moment onwards, British unions were somewhat weakened. With the tough handling of the NUM strike, Margaret Thatcher consolidated her reputation as the ‘Iron Lady’, a nickname that became associated with her uncompromising politics and the tough leadership style. As the first female prime minister of UK, she implemented policies that became known as ‘Thatcherism’.

I spent the summer of 1979 in London soon after Margaret Thatcher became the Prime Minister of UK. On April 12, 1984, I served her dinner at a royal banquet held in honour of the Queen of England at the Dorchester. When she was ousted from the position of the Prime Minister after a cabinet revolt in 1990, I was living in London again. On November 28, 1990, I watched her final speech as the Prime Minister in the House of Commons, and leaving her office and residence in Downing Street in tears. A few years after that, I hosted her successor, John Major in my office at Le Meridien Jamaica Pegasus Hotel.

Terrorism

The civil war in Sri Lanka which commenced in July 1983 before we left for UK was getting worse. Although we thought that UK was peaceful, that country had its large share of terrorism, predominately in the hands of the Irish Republican Army (IRA). During my first stay in UK in 1979, I was shocked to see on TV that IRA claimed responsibility for the assassination of Admiral Lord Louis Mountbatten. As the supreme allied commander for Southeast Asia, he had commanded the British troops from his base in Ceylon during the latter part of World War II.

My first direct exposure to terrorism in UK was when I was working at Bombay Brasserie in Kensington, London. “Chandi, be careful, when going home today. Avoid the circle line and don’t go near Knightsbridge. IRA bombed Harrods!”, an Indian work colleague warned me. Harrods, world famous upmarket department store in the affluent Knightsbridge district, near Buckingham Palace, had been subject to two IRA bomb attacks earlier. Although the IRA had sent a warning 37 minutes before a car bomb that exploded outside Harrods on December 17, 1983, the area had not been evacuated. Due to this car bomb, six people died and 90 were injured. This was the 40th terrorist attack in UK since early 1970s.

On October 12, 1984, a powerful IRA bomb went off with deadly effect in the Grand Hotel in Brighton, England, where members of Britain’s Conservative Party were gathered for a party conference. IRA’s target was to assassinate the British Prime Minister and the other key members of her government. The bomb ripped a hole through several storeys of the 120-year-old hotel.

When the bomb went off just before 3:00 am, Margaret Thatcher was still awake at the time, working in her suite on her conference speech for the next day. The blast badly damaged her suite’s bathroom, but left its sitting room and bedroom untouched. She and her husband were fortunate to escape serious injury, although 34 people were injured and another five killed. The next day, when we watched her on TV delivering an excellent party conference speech with a brave face, I remarked to my wife, “She truly is a real Iron Lady!”

On October 31, 1984 when I was going to work at the Dorchester, I heard a loud celebration in some parts of London. Some Sikh men were lighting fire crackers while celebrating and distributing sweets and fruits to onlookers. I assumed that it must be a Sikh holiday event, but soon realised that they were celebrating an assassination. Indian Prime Minister Indira Gandhi had been assassinated at her residence in New Delhi, early morning that day, by her Sikh bodyguards.

I knew that five months prior to that day, Indira Gandhi had ordered the removal of a prominent orthodox Sikh religious leader and his rebel followers from the Golden Temple of Harmandir Sahib in Amritsar, Punjab. The collateral damage included the death of approximately 500 Sikh pilgrims. The military action on the sacred temple was criticized both inside and outside India. Indira Gandhi’s assassination sparked four days of riots that left more than 8,000 Indian Sikhs dead in revenge attacks. The world is a dangerous place to live in.

Features

Are we witnessing end of globalisation? What’s at stake for Sri Lanka?

Globalisation can be understood as relations between countries, and it fosters a greater relationship between countries that involve the movement of goods, services, information, technology, money, and human beings between countries. These relationships transcend economic, cultural, political, and social contexts.

Globalisation in the modern world today is a significant shift from the past. Globalisation in the modern world today is a state in which the world becomes interconnected and interdependent. This change occurs due to better technology, transport, communication, and foreign trade.

Trade routes have joined areas for centuries. The Silk Road and colonial sea trade routes are the best examples. But today, nobody can match the speed and scope of globalization.

Globalisation began to modernise after World War II. During this time, countries came to understand that they had to work together. They wanted to have economic cooperation and peace so that they would not fight any more. These significant institutions united countries for political and economic purposes and advantages. They allow free movement of products, services, and capital between countries. It encourages cooperation all over the world.

The second half of the 20th century saw fabulous technological advances. These advances sped up globalisation. The internet changed everything. It changed the way people communicate, share information, and do business. Traveling became faster and more efficient. Products and humans travel from one continent to another in record time. Companies can now do business globally. They outsource jobs, get access to global markets, and use global supply chains. This was the dawn of multinational firms and a global economy.

Flow of information is one of the characteristic features of the current age of globalisation. The internet allows news, ideas, and culture to be shared in real-time. Societies are experiencing unprecedented cultural interconnectedness. This has led to controversy over cultural sameness and dissimilation of local cultures. For example, the same is observed within countries too. In countries such as Sri Lanka the language differences between districts have become a non-issue, and the western province’s language has paved the way for others to emulate. Globalisation has allowed millions of individuals to lift themselves out of poverty, especially in Asia and Latin America. It does this by creating new employment opportunities and expanding markets. It has also increased economic inequalities, though. Wealth flows to those who possess technology and capital. Poor workers and communities are unable to compete regionally or internationally. Some countries have seen political backlash. In these countries, some people feel left behind by the benefits of globalisation.

Modern globalisation has a lot to do with environmental concerns. More production, transportation, and consumption have destroyed the planet. These are pollution, deforestation, and climate change. Global issues need global solutions. That is why international cooperation is essential in solving environmental problems. The Paris Climate Agreement is one such international effort to cooperate. There are constant debates regarding justice and responsibility between poor and rich countries.

Modern-day globalisation deeply influences our daily lives in many ways. It has opened up possibilities for economic growth, innovation, and cultural exchange. However, it also carries with it dire consequences like inequality, environmental destruction, and displacement of culture. The future of globalisation will be determined by the way we handle its impact. We have to see to it that its benefits are distributed evenly across all societies.

Tariffs are globalising-era import taxes. Governments levy them to protect domestic firms from foreign competition. But employed ruthlessly and as retaliation like today, and they can trigger trade wars. Such battles, especially between big economies such as the U.S. and China, can skew trade. They can destabilise markets and challenge the new era of globalisation. Tariff wars will slow or shift globalisation but won’t bury it.

Globalisation is not just a product of dismantling trade barriers. It is the product of enormous forces like technology, communications, and economic integration in markets across the globe. Tariffs can limit trade between countries or markets. They cannot undo the fact that most economies in the world today are interdependent. Firms, consumers, and governments depend on coordination across borders. They collaborate on energy, finance, manufacturing, and information technologies.

However, the effects of tariff wars should not be downplayed. Excessive tariffs among dominant nations compromise international supply chains. This also raises the cost for consumers and creates uncertainty for investors. The 2018 U.S.–China trade war created billions of dollars’ worth of tariffs. It also lowered the two countries’ trade. Industries such as agriculture, electronics, and automotive manufacturing lost money. These wars can harm international trade confidence. They also discourage higher economic integration.

There are some nations that are facing challenges. They are, therefore, diversifying trade blocs. Others are creating domestic industries. Some are also shifting to regional economic blocks. This may result in more fragmented globalisation. Global supply chains can become short and local. The COVID-19 pandemic and tariff tensions forced countries to re-examine the use of foreign suppliers. They began to stress self-sufficiency in vital sectors. These are medicine, technology, and food production.

Despite these trends, globalisation is not robust. The global economy can withstand crises. It does so due to innovation, new trade relations, and digitalisation. E-commerce, teleworking, and online communication link people and businesses across the globe. Sometimes these links are even stronger than before. Countries need to come together in order to combat challenges like climate change, pandemics, and cybersecurity. This is happening even as economic tensions rise.

Tariff wars can disrupt trade and create tensions.

However, they will not be likely to end globalisation, but instead, they reshape it. They might change its structure, create new partnerships, and help countries find a balance between openness and security. The globalization forces are strong and complex. They can be slowed down or reorganized, but not readily undone. The future of globalisation will depend on how countries strike their economic interests. They must also recognise their interdependence on each other in our globalised world. The world economy has a tendency to change during crises.

It does this through innovating, policy reform, building strong institutions, and changing economic behavior. But they also stimulate innovative and pragmatic responses by governments, companies, and citizens. The world economy has shown that it can heal, change, and change after crises like financial downturns, pandemics, and geo-political conflicts. One of the more notable examples of economic adjustment occurred in the 2008 global financial crisis. The crisis started when the housing market in the U.S. collapsed. The big banks collapsed, and then the effects spilled over to the world. This led to recessions, very high unemployment levels, and a drop in consumer confidence. In response, central banks like the U.S. Federal Reserve and the European Central Bank acted very quickly. They cut interest rates to near zero. They also started large-scale quantitative easing. Governments spent stimulus money in their economies. They assisted in bailing out banks and introduced tax-tight financial regulations. These actions stabilised markets and ultimately restored economic growth. The crisis also led to new financial watchdog mechanisms. One example is the Financial Stability Board, which has the objective of avoiding such collapses in the future. The COVID-19 pandemic created a unique crisis.

It reached health systems and economies globally. In 2020, the world suddenly stopped. Lockdowns and supply chain disruptions followed. This led to a sharp fall in GDP in almost all countries. Sri Lanka experienced it acutely. However, the world economy has adapted at a breathtaking speed. Remote work and online shopping flourished, driven by digital technology. Firms transitioned to new formats like contactless offerings, delivery platforms, and remote platforms. Governments rolled out massive stimulus packages to businesses and employees. Central banks infused liquidity to support financial systems. International cooperation on vaccine development and distribution also helped accelerate economic recovery. By 2021 and 2022, various economies were quicker to recover than expected, though unevenly by region. Another outstanding one is the manner in which economies adapted to geostrategic struggles:

The war of 2022 between Ukraine and Russia ravaged across world markets of food and energy, with special impact on Europe and the Global South.

European nations moved swiftly to abandon Russian natural gas. European nations also looked around for other sources of energy and increased usage of renewables. While shock caused inflation as well as supply shortages to a peak first, markets began to shift ultimately. And world grain markets looked elsewhere and established new channels of commerce. Such changes show the ways that economies can change under stress, even if ancient structures are upended. Climate change is demanding long-term change in the world economy.

The climate crisis isn’t a sudden crisis, like war or pandemic. But it’s pushing nations and businesses to make big changes. Green technologies are on the rise. Electric vehicles, solar and wind power, and carbon capture are the best examples. These technologies are indicative of how economies address environment crises. Financial institutions and banks are now embracing sustainable investing guidelines. Countries are uniting in a low-carbon future under the terms of the Paris Climate Accord. Technology is leading economic resilience.

The digital economy is going stratospheric—AI, cloud computing, and e-commerce are the jetpack! These technologies enable companies to be agile and resilient. Consider the pandemic and the financial crisis, for instance. Technology businesses did not just survive; they flew like eagles. They gave us remote work tools, digital payments, and virtual conversations, allowing us to stay connected when it was most important. These innovations have irreversibly shifted the terrain of worldwide business and work. The global economy’s history is marked by crises and its capacity to adapt and transform in response. The global economy proves strong during financial crises, pandemics, conflicts, and climate issues. Resilience shines through innovation, teamwork, and strategic adjustments. Though challenges linger and vulnerabilities remain, we’re not without hope.

Learning from crises helps us fortify and adapt our systems. This adaptability signals a promising evolution for the global economy amid future uncertainties.

The current trade war, especially between the United States and China, is reshaping globalization. It may lead to a new form of it. These tensions do not terminate globalization. Instead, they push it to evolve into a more complex and regional form. The new model includes economic factors. It also includes political, technological, and security factors. This leads to a world that remains interconnected but in more cautious, selective, and fragmented ways.

Trade wars tend to begin when countries want to protect their industries.

They might want to lower trade deficits. They also respond to unfairness, including intellectual property theft or state subsidies. The ongoing trade war between China and the U.S. has seen massive tariffs, export quotas, and increasing geopolitical tensions. This is a sharp departure from the post-Cold War era, which saw more free and open trade. Now, companies and governments prepare for everything. Safety and national interests are their concerns. This change is reflective of a trend that some experts call “de-risking” or “strategic decoupling.” One of the most obvious signs of this new course is the reorganization of global supply chains.

Many global companies want to diversify away from relying on one country. They especially want to decouple from China for manufacturing and raw materials. They diversify production by investing in different regions. It is called “China plus one.” It means relocating operations to locations like Vietnam, India, and Mexico. This relocation takes global supply chains from centralized to more regionalized and redundant networks. These networks prepare for future shocks. Moreover, technology and digital infrastructure have an increasing role in this new globalization.

Trade tensions are an indication of the strategic value of semiconductors, telecommunications, and artificial intelligence. Nations are realizing that technology is a national security issue. Therefore, they have invested in their local capabilities and restricted foreign technologies’ access. The U.S., for example, has put export restrictions on high-end microchips and blocked some Chinese technology companies from accessing its market. China and other nations have increased efforts in developing independent ecosystems for technologies. This has given rise to parallel technology realms. This could result in a “bifurcated” global economy with different standards and systems. The current trade war is also strengthening the advent of regional trading blocs.

Global trade agencies like the World Trade Organization are getting weakened. This is owing to the fact that the world’s major nations are competing with one another. Hence, the nations are currently opting for regional agreements to develop economic cooperation. Discuss the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP) and the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) in Asia. And let’s not forget the United States–Mexico–Canada Agreement (USMCA). Collectively, these agreements represent a new era of globalization. It’s no longer a free-for-all; rather, it’s a strategic web spun with trusted partners and regional ambitions resulting in ‘islands’ or ‘regions’ of globalization. The new model of globalization creates greater independence and security for some but presents issues.

The countries that previously prospered from the exportation of goods and involvement in the global market may face greater challenges. As protectionism rises and competition becomes greater, customers may pay more. Economic inefficiencies are a likely reason. Additionally, the disintegration of international institutions may stop countries from agreeing on important issues. Problems like global warming, pandemics, and economic downturns can become harder to resolve. The current trade war will not end globalization, but it is reshaping it. We see a new type of globalization that is fragmented, regional, and strategic in character. Countries are still interdependent, but such economic dependency is underpinned by trust, security, and competition. Globalization is changing, so we must balance these changes with the imperatives of cooperation in our globalized world.

New types of globalization include regional trade blocs, reshaping supply chains, tech decoupling, and growing geopolitical tensions.

For Sri Lanka, the changes have far-reaching consequences.

Being a small nation strategically located, Sri Lanka relies on trade, tourism, and foreign investment. Globalization is, however, more fragmented and politicized and security-oriented. This offers opportunities and challenges for Sri Lanka. To survive, the country must reform its economic policies. It must diversify relationships and maneuver the rival interests of global powers with caution.

One of the most immediate effects of the new globalization is realigning global supply chains.

Multinationals want to wean themselves from China. They want to shift production elsewhere. Sri Lanka can be a new hub for light manufacturing, logistics, and services. Being located on key shipping routes in the Indian Ocean means that it is a vital node in global ocean trade. Sri Lanka can lure more foreign investment by improving its infrastructure, bolstering digital strength, and upgrading the regulations. This would help firms to open up business. This would create employment as well as improve export-led growth. But the shift towards regionalism in global trade also poses danger.

The rest of the countries outside these alignments might be left out as major economies create closed trading blocs. Examples include the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) and bilateral agreements like the Indo-Pacific Economic Framework. Sri Lanka is not part of most of the world’s biggest trade blocs, limiting its access to large markets and preferential trade conditions. Exclusion could make exports less competitive. It could also reduce the nation’s appeal as an international production base. To fulfill this, Sri Lanka must pursue trade agreements with regional powers like India and ASEAN nations in order to keep up with shifting trade networks. One key feature of the new era of globalization is a focus on ‘technological sovereignty’.

This includes the rise of alternative digital ecosystems, especially between China and the US. Sri Lanka must manage the tech divide wisely. Countries are closing doors to other people’s technologies and creating their own networks. Cyber security, digital infrastructure, and data governance require investments. Sri Lanka also needs to balance embracing new technology while preserving its digital sovereignty. Dependence on technology from a single country could yield dangers, as digital tools will be the main movers in the realms of governance, finance, and communication. Geopolitical competition, especially in the Indo-Pacific, also affects Sri Lanka’s economic and strategic location.

The island’s location has drawn China and India and Western nations. China’s involvement in Sri Lankan infrastructure projects, such as the Hambantota Port and the Colombo Port City, has yielded economic advantage as well as concerns regarding debt dependence and strategic control. Meanwhile, India and its allies have expressed interest in balancing Chinese power in the region. This is a sensitive balance that Sri Lanka has to exercise strategic diplomacy to reap foreign investment without being entangled in great power rivalry or compromising sovereignty. In addition, economic resilience in the face of global shocks—such as the COVID-19 pandemic, energy shocks, and food crises—has emerged as a top priority in the new era of globalization.

The recent economic slump in Sri Lanka, marked by a sovereign default, foreign exchange crises, and inflation, underscored the country’s vulnerability to global shocks. These events underscore the need for greater economic diversification, sound fiscal management, and long-term development. Sri Lanka must build stronger domestic industries, shift to clean energies, and transform regional supply systems that are less vulnerable to shocks from the outside. Generally speaking, therefore, the new patterns of globalization present Sri Lanka with a risk-laden world of possibility too.

While transforming global patterns of trade and investments creates new doors to economic growth, it steers the country towards more aggressive competition, geopolitical tensions, and internal vulnerabilities. To thrive in this fast-evolving world, Sri Lanka must adopt an assertive strategy of regional integration, technological resilience, strategic diplomacy, and inclusive economic reform. On the way, it can transform foreign uncertainty into a platform for sustainable and sovereign development.

by Professor Amarasiri de Silva

Features

Fever in children

by Dr B.J.C.Perera

by Dr B.J.C.Perera

MBBS(Cey), DCH(Cey),

DCH(Eng), MD(Paed), MRCP(UK), FRCP(Edin), FRCP(Lond), FRCPCH(UK),

FSLCPaed, FCCP, Hony. FRCPCH(UK), Hony. FCGP(SL)

Specialist Consultant Paediatrician and Honorary Senior Fellow, Postgraduate Institute of Medicine, University of Colombo, Sri Lanka.

Joint Editor, Sri Lanka Journal of Child Health Section Editor, Ceylon Medical Journal

Fever is a common symptom of a variety of diseases in children. At the outset, it is very important to clearly understand that it is only a symptom and not a disease in its own right. When the body temperature is elevated above the normal level of around 98.6 degrees Fahrenheit (F) or 37 degrees Celsius (C), the condition is referred to as fever. It is a significant accompanying symptom of a plethora of childhood diseases. All children would get a fever at some time or another in their lives, and in the vast majority of cases, this is due to rather mild illnesses, and they are completely back to normal within a few days. Some may have a rather low-grade fever, while others may have quite a high fever. However, in certain situations, fever may be an important indication of an underlying serious problem. The significance depends entirely on the circumstances under which this occurrence is seen.

Irrespective of the actual underlying reason for the fever, the basic mechanism of causation of fever is the temporary resetting of the temperature-regulating thermostat of the brain to a higher level. The consequences are that the heat generated within the body is not effectively dissipated. It is merely a body response to a harmful agent and is a very important defence mechanism. Turning up the core temperature is the body’s way of fighting the germs that cause infections and making the body a less comfortable place for them. However, less commonly, it is also a manifestation of other inflammatory disorders in children. The significance of fever in such situations is a little bit different to that which is seen as a response to an infection.

The part of the human brain that controls body temperature is not fully developed in young children. This means that a child’s temperature may rise and fall very quickly and the child is also more sensitive to the temperature of his or her surroundings. Although parents often worry and get terribly scared with the child developing fever, it does not cause any harm by itself. It is a good thing in the sense that it is often the body’s way of fighting off infection.

It is quite important to note that the actual level of the temperature is not always a good guide to how ill the child is. A simple cold or other viral infection can sometimes cause a high fever in the region of 102 to 104 degrees Fahrenheit or 39 to 40 degrees Celsius. However, this does not always indicate a serious problem. It is also true to say that some more sinister infections could sometimes cause a much lower rise in the body temperature. Because fevers may rise and fall, a child with a fever might experience chills and shivering as the body tries to generate additional heat as the body temperature begins to rise. This may be followed by sweating as the body releases extra heat when the temperature starts to drop. Children with fever often breathe faster than usual and generally have a higher heart rate. However, fever accompanied by obvious difficulties in breathing, especially if the breathing problems persist even at times the temperature is normal is of significance and requires urgent medical evaluation of the situation. Generally, in the case of children, the way they act is far more important than the reading on the thermometer, and most of the time, the exact level of a child’s temperature is not particularly important, unless it is persistently very high.

Although many fevers need just simple remedies, under certain conditions the symptom of fever needs rather urgent medical attention. This is the case in babies younger than three months. Same is true even in a bigger child if the fever is accompanied by uncontrollable crying or pain in the neck with a severe headache. Marked coughing and or difficulty in breathing coupled with fever needs to be medically sorted out. Fever combined with pain and difficulty in passing urine, significant tummy pains or marked vomiting and diarrhoea too would need medical attention. Reddish rashes and bluish spots on the skin with fever also need to be seen by a doctor. The illness is probably not serious if a child with a history of fever is still interested in playing, is eating and drinking well, is alert and smiling, has a normal skin colour and looks well when his or her temperature comes down. However, even with rather low levels of fever, under certain conditions, medical attention should be sought. In situations such as when the child seems to be too ill to eat and drink, has persistent vomiting or diarrhoea, has signs of dehydration, has specific complaints like a sore throat or an earache or when fever is complicated by some other chronic illness, it is prudent for him or her to be seen by a qualified doctor.

One could take several steps to bring down a fever. It is very useful to remove most of the clothes and keep under a fan to facilitate heat loss from the body. If there is no fan available, one could try fanning with a newspaper. A very effective way of bringing down a temperature is to sponge the body with a towel soaked in water. The water must be at room temperature or a bit higher. One should not use ice or iced water on the body. Ice will lead to contraction of the blood vessels of the skin and the purpose would be lost as more heat will be conserved within the body. There is no evidence that ice on the head helps to bring down the fever or to prevent a convulsion. If a medicine is to be used, paracetamol is probably as good as any other drug, but the correct dosage according to the instructions on the container should be used for optimal benefit. The best way of calculating the appropriate dose is by using the body weight. It is very important to stress that aspirin and aspirin-containing medications should not be used in children, merely to bring down a fever.

A child with fever loses a considerable amount of fluid from the body, particularly due to sweating. It is beneficial to ensure that the child drinks plenty of fluids. A good index of the adequacy of fluid intake is the passing of normal amounts of urine. A reduced solid food intake would not matter that much just for a couple of days of fever, but in prolonged fevers adequate nutrition too becomes quite important. A child with a high temperature also needs rest and sleep. They do not have to be in bed all day if they feel like playing, but they must have the opportunity to lie down. Sick children are often tired and bad-tempered. They sleep a lot, and when they are awake, they want their parents around all the time. Perhaps it is quite useful to spoil them a little bit when they are ill and to read to them, play with them or just spend time with them. It is best to keep a child with a fever home and not send him or her to school or child care. Most doctors would agree that in simple fevers, it is quite satisfactory for the child to return to school or child care when the temperature has been normal for over 24 hours.

Trying to get the temperature down would make the child more comfortable. However, it is not essential to get it down to normal and to keep it there scrupulously. Parents often worry that either the fever simply refuses to abate or springs up again after a couple of hours. It must be realised that certain fevers have to run their course and will not come down to normal in a hurry, despite whatever measures that are undertaken. This is particularly true of viral fevers. Some parents are terribly worried at the slightest elevation of the temperature and go running to doctors looking for a “magic cure” for the fever. Many fevers do not need urgent medical attention and one could watch it for a few days and see how it progresses. Yet for all that, if there are some worrying signs then it is advisable to seek advice from a qualified doctor.

It is a familiar occurrence that many people believe that a high fever is quite dangerous. Fever by itself has no major long-lasting effects. If one appreciates that high fever is just a symptom and that it is only a reaction of the body to something untoward going on, then it is easy to consider it to be just like any other symptom of a disease. Some are also under the misconception that a high fever could cause a convulsion. This is not always the case, and a convulsion would occur only in those children who have the constitutional tendency to get them. Convulsions are not always related to high fever, and in those who are susceptible, even moderate and sometimes mild fever could trigger a convulsion. High fever does not lead to lasting brain damage in its own right either. Fever is sometimes an indication of a significant infection, but in those circumstances, the primary disease itself is the real problem. In situations where medical help is desirable, what is most important is the way a fever is sorted out and some kind of a diagnosis being made as to the real cause of the fever. The crucial component of the treatment of a fever caused by an underlying problem is the treatment of the root cause.

Features

Robbers and Wreckers

To quarrel with them is a loss of face

To have their friendship is a sad disgrace

Those lines by Bharavi were written after the fourth century A.D. when Sanskrit was already a purely literary language.

We have had the spectacle of a reporter in DC asking Donald Trump whether he regrets his lying all the time every day of his life. And, Trump responded “What did you say?” and one could see that such a possibility had never occurred to him: he was genuinely baffled.

The question here and now is whether such a thought has ever come to Anura Kumara Dissanayake and Harini Amarasuriya, both obedient servants of the US and India. For example, the prathigna given by Amarasuriya as she was sworn in by AKD as Prime Minister in a Cabinet of three. That their doings are in line with the desires of Ranil Wickremesinghe (and maybe the “aspirations” of their buddies) would translate also to the cover up of his bringing in Arjuna Mahendran, the son of a Chairman of the UNP, to trash the Central Bank and execute Ranil’s bond scam.

In the matters of managing our economy and respecting our age-old culture this lot have shown us glimpses of the lunatic self-applause that define Trump’s doings. As phrased by a commentator in the U K Guardian a few days ago Trump’s endeavours “weren’t about Making America Wealthy Again. This was much more primal. Sticking it to all the people who had laughed at him over the years. His bankruptcies. His hair. His orangeness. His stupidity. Sticking it to all those who had taken him to court and won. Now he was the most powerful person in the world. He had the whole world watching as he messed it up. He could do what he liked.”. It’s quite obvious that the last is how AKD, HA, Yapa and the top tier of those most culpable have read their horoscopes: they do not expect to be held accountable

“The U.S.’s new tariff policy reflects a broader shift away from globalisation and towards economic nationalism and national balance sheet economic model approach”. So wrote a self-styled Business Cycle Economist last week. That is the kind of delusion that ‘growth-friendly’ market theory such ‘economists’ are trained to shove down the throats of politicians possessed of just about the bit of wit required to enrich themselves in tandem with the IMF and those entrepreneurs it supports.

At this point we should note also that Trump’s new wave of tariffs was harshest on Cambodia, Myanmar, Thailand, Vietnam and Sri Lanka––all, coincidentally, in addition to their strategic importance for war-mongers, Buddhist countries.

How closely those who call the shots among the power-wielders here follow Trump is seen in their response or lack of one to the earthquake that has devastated Myanmar and Thailand a week ago. The USA has been salivating over the riches of Myanmar for a long time, confident that Aung Suu Kyi would deliver them on a platter. That no doubt was the object of the aragalaya here and seems within reach for India now.

For months now, from 2022 at least, there have been markers that showed who was running the Janatha Vimukthi Peramuna (so calling themselves) and what their agenda was with respect to our country and her people. An early eruption that showed their hand was that aragalaya‘. It was designed to ensure a regime change that would place, let us for convenience say, Adani in charge. It involved, as a first step, getting Gotabhaya out of the presidency. That it was so was also shown two years ago in the London Review of Books by Pankaj Misra in an essay titled “The BIG CON” on Modi’s India. In which Gotabhaya and Adani are mentioned and the above object specified.

Misra’s latest work has been on “The World After Gaza” – a reference not without its applications not only to Modi’s support for Adani in Haifa, but to the ridiculous and altogether culpable gestures of friendship towards the US-Israeli led coalition of criminals shown by Ranil Wickremasinghe and associated Colombians who succeeded him. Haifa is the largest port in that segment of occupied Palestine and the Trump group also has had a stake in it.

I shall pause here with the concluding lines of Bharavi’s quatrain.

One of sterling judgment realizes

What fools are worth and foolish ones despises.

by Gamini Seneviratne

-

Business5 days ago

Business5 days agoColombo Coffee wins coveted management awards

-

Features6 days ago

Features6 days agoStarlink in the Global South

-

Features1 day ago

Features1 day agoRobbers and Wreckers

-

Features3 days ago

Features3 days agoSri Lanka’s Foreign Policy amid Geopolitical Transformations: 1990-2024 – Part III

-

Features6 days ago

Features6 days agoModi’s Sri Lanka Sojourn

-

Midweek Review3 days ago

Midweek Review3 days agoInequality is killing the Middle Class

-

Features5 days ago

Features5 days agoSri Lanka’s Foreign Policy amid Geopolitical Transformations: 1990-2024 – Part I

-

Features4 days ago

Features4 days agoA brighter future …