Features

From abolishing the Senate to adopting a third new constitution

The 50-year Constitutional Odyssey:

by Rajan Philips

There are three infliction and, perhaps also, inflection points to this article. First, is the sequel to my article two weeks ago (Sunday Island, October 10) where I alluded to the possibility of Sri Lanka’s parliament restoring itself and changing the ways of the regime between now and the next elections. In a situation of unprecedented crises, changing the ways of the regime is more vital than waiting for a potential electoral regime change three years from now. That was my plea, if not contention. I did not write last week, so it is carryover business this week. It is also the first point of infliction on the always indulgent editor and the more ageing than ageless readers of English newspapers.

The second point emanates from the visit (also on October 10) by President Gotabaya Rajapaksa to the Gajaba Regiment Headquarters, at Saliyapura, Anuradhapura, to commemorate the 72nd Anniversary of the Sri Lankan Army. In his speech to mark the military occasion, President Rajapaksa included a promissory note on the Constitution, that he will be “bringing in (of) a new Constitution,” as he had promised in November 2019, and that it “will be delivered within the next year.” The President’s obiter of reassurance literally took away the wind out of whatever parliamentary reform sails that I might have been hoping to use for my unsolicited purpose.

The third and the most obviously inflexion point, thanks entirely to Dr. Nihal Jayawickrama and the article he wrote last Sunday (October 17), is the 50th anniversary of the death, on October 2, 1971, of the Senate of Ceylon at the young age of 24. It was death by legislative euthanasia, brutally premature at so young an age and for a body that bore no incurable ill. It was a rather bad riddance of a good body.

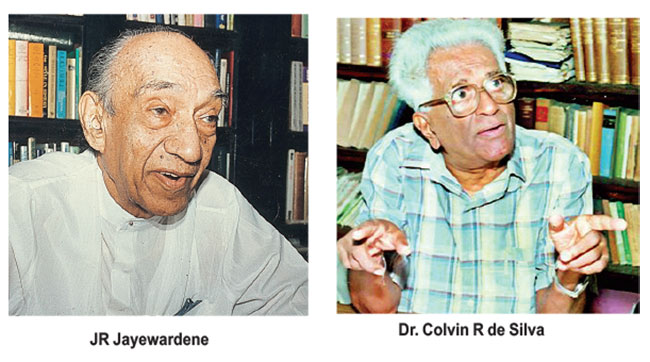

Dr. Jayawickrama’s commemorative piece is quite remarkable at many levels. He neither asserts that the Senate deserves what it got, nor is he patently critical that it was put down at all. He is fair in his account of the purpose for which the Senate was created and the manner in which it played its constitutionally assigned role despite its lopsided composition and nominating procedure. He does not cite Sir Ivor Jennings’s scholarly cynicism that an unelected Senate can only be either “mischievous” (when it goes against the elected House) or “superfluous” (when it passes what has already been passed by the House); nor does he refer to Dr. Colvin R de Silva’s forceful contention that the Senate that “frustrates the will of the people” was one of the “five major defects” of the Soulbury Constitution.

That contention alone was enough to indicate the Senate’s fate in the new constitution that was being prepared by the United Front government. What came as a surprise at that time was the manner of the Senate’s riddance by an amendment to the Soulbury Constitution rather than through the new constitution. What struck me in the story of that riddance recounted by Dr. Jayawickrama was the pattern of disownment by all the key players in the parliamentary drama that began with a Bill to amend the Soulbury Constitution to save the SLFP MP for Ratnapura, Nanda Ellawala, from expulsion over a conviction and imprisonment, and ended with a Bill to amend the same constitution to abolish the Senate. To wit, Dr. Colvin R de Silva who introduced the first Bill in parliament, in July 1970, made it a point to ‘disown’ the bill by indicating that the Bill had been drafted in the Ministry of Justice and not by ‘his’ Ministry of Constitutional Affairs. And the disclaimers continued even as the Senate was let to die.

Committee of Experts

Nihal Jayawickrama’s article also provides a foil for contrasting the current urge to create a new constitution with the circumstances 50 years ago when Sri Lanka began its long odyssey of constitutional makeovers. No one would have thought then that it would come this far and could go still further. His intervention is particularly striking because he might be the only person alive who was closest to the making of the First Republican Constitution of 1972. He is also expertly familiar with the genesis and entrenchment of the 1978 Constitution. And perhaps the only other constitutional scholar of the same vintage is Prof. Savitri Goonesekere. If I am not mistaken, I do not think there is anyone alive today, who was associated with the making of the 1978 Constitution.

On the other hand, and I do not say this to be uncharitable, in President in Gotabaya Rajapaksa, we have the first Sri Lankan to become the most powerful person in the country with the least familiarity with anything constitutional. And it gets worse. In 1970, Parliament was the master of the country’s constitutional destiny, not only by representation but also by virtue of its legal luminaries. The finest legal minds in the country were in parliament, with the House and the Senate combined. Today’s parliament is not only bereft of talent, but is also powerless in spite of the government’s two-thirds majority. Worse, it is totally sidelined from the making of the new constitution.

That task has been outsourced to a committee of experts none of whom are in parliament, or ever held any elected office. Without tracing the bio-data of individual committee members, I will not be too far off the mark to suggest that with the exception of Prof. GH Pieris, all the other members of the committee would have been in their early twenties at most when Sri Lanka began its constitutional odyssey in 1970. If they were all kids then, they would do well to read Dr. Jayawickrama’s article on the Senate and reflect on what they are about to do now as grownups in creating a new constitution for President Gotabaya Rajapaksa.

If they are also keeners, and they ought to be so to be considered ‘experts’, it is reasonable to assume that they would have by now had some discussions with Dr. Jayawickrama to benefit from his experience and expertise. If not, it’s a shame. It is a travesty that this government is hellbent on creating a new constitution without consulting with or getting advice from people like Prof. Savitri Goonesekere or Dr. Nihal Jayawickrama. Travesty though it is, it should not come as a surprise to anyone considering the way the government availed itself of expert advice on Covid-19.

The impetus for the constitutional change in 1970-72 came from a side remark (obiter) in a 1964 Privy Council ruling that highlighted the legislative limitations of the Sri Lankan (then Ceylon) parliament. Although the contentious Privy Council obiter had been around since 1964, it became a political issue in parliament only in 1969, and it became an election issue in the April 1970 elections. The landslide victory of the United Front Parties in 1970 and the appointment of Dr. Colvin R de Silva as Minister of Constitutional Affairs eventually led to Sri Lanka becoming a Republic with a new constitution in 1972.

The inspiration for the 1978 constitutional overhaul came almost entirely from JR Jayewardene’s idiosyncratic liking for a presidential system of government. He was fortuitously able to use the flexibility of the Colvin constitution to create a far more rigid constitution predicated on an elected executive presidential system. He was also fortunate in getting to be the country’s first and only executive president without an election. Ever since, the constitutional debate has been about abolishing or significantly modifying the presidential system. Until now. And nobody knows why there should be a new constitution now to continue the same presidential system.

Why a new constitution?

Do the members of the experts committee know why Sri Lanka needs a new constitution? Other than the reason that President Rajapaksa wants to have one to show that he kept his promise that no one paid attention to. Going by some of the reasons for a new constitution provided by self-proclaimed patriots and nationalists, Sri Lanka needs a new constitution to enshrine its civilizational heritage. Its greatest heritage, Buddhism, needs no textual enshrinement by a committee of worldly experts. Constitutionally, or textually, does it mean that Chapter II of the Constitution will be expanded to fill a whole page instead of the four and half lines there are now? How will that ennoble an already great and noble religion, or edify its faithful followers?

A starkly different reason is apparently to constitutionally enshrine the implications of the 2009 war victory over the LTTE? How is that going to be textualized; in the preamble or Svasti to the current Constitution? Will it be before or after the assurances about Human Rights and the Independence of the Judiciary, in the preamble, that is? Is the purpose of enshrining triumphalism to ward off outside calls for investigating war crimes allegations? How can new constitutional provisions prevent anybody from saying or doing anything outside the country? Can a new constitution prevent another Easter tragedy, or will it unpack secrets of the last one? Cardinal Malcolm Ranjith is in no mood to trust any this-worldly Sri Lankan government or leaders. He is warning about curses and he is calling for divine intervention by the God of Israel and is looking for intercession by the silver-tongued Saint of Padua.

When the debate was about abolishing the presidency the counter-argument was that the presidency must be retained to check and contain the devolved provinces. The key players in the current Administration including President Rajapaksa himself were strong proponents of abolishing the Provincial Councils and rescinding the 13th Amendment. Now there are no active Provincial Councils to abolish as they are all dissolved. And with the government’s two-thirds majority the PCs can be abolished the same way the Senate was abolished 50 years ago. There might be a snag though if the courts were to say that Provincial concurrence is needed for their abolishing even though no concurrence is needed for their indefinite dissolution.

Surprisingly, or not, the government is now keen to go ahead with the Provincial Council elections as soon as possible, with or without a new constitution. Several reasons are being touted for this new shift. India’s hand in this is apparently not so hidden.

Second tier SLPPers are said to be getting restless without provincial offices and perks, and they need to be rewarded and kept contented. Third, a chief characteristic of Rajapaksa politics is the restless urge to keep validating themselves by constantly calling elections in the hope of winning them all the time. Their public support is said to be at its lowest point in the 16 years since they first hit the presidential jackpot in 2005. But they know it is better to test the pulse early and consolidate themselves before things get “worser and worser” as Muhammad Ali used to say. Finally, Provincial Council elections could be a trial run for a referendum that will be necessary for adopting a new constitution.

So, one needs to go back to the Committee of Experts and ask them – which of these reasons do they find to be so compelling as to devote their efforts and energies to producing a new constitution? It was the arrogance of two-thirds majority power that precipitated the abolishing of the Senate in 1971. Fifty years later, there is no palpable arrogance in spite of power, but there is great potential for its abuse out of abundance of ignorance. The question to the Committee of Experts is whether they are going to be aiding and abetting a potential abuse of power in creating a new constitution?

To circle back to the first point of infliction that I started with, it would be a fool’s paradise to discuss parliamentary reform when the government’s priority is to swing the constitutional wrecking ball at parliament and everything else that is still working in Sri Lanka. We can only wait and see how extensive the wreckage is going to be before talking about any reform. What if some or all in the Committee of Experts want to have no part of this wreckage and honourably excuse themselves from the Committee? Stranger things have happened.

Features

Sri Lanka deploys 4,700 security personnel to protect electric fences amid human-elephant conflict

By Saman Indrajith

Sri Lanka has deployed over 4,700 Civil Security Force personnel to protect the electric fences installed to mitigate human-elephant conflict, Minister of Environment Dammika Patabendi told Parliament on Thursday.

The minister stated that from 2015 to 2024, successive governments have spent 906 million rupees (approximately 3.1 million U.S. dollars) on constructing elephant fences. During this period, 5,612 kilometers of electric fencing have been built.

He reported that between 2015 and 2024, 3,477 wild elephants and 1,190 people lost their lives due to human-elephant conflict. Electric fences remain a key measure in controlling this crisis, he added.

Between January 1 and 31, 2025, 43 elephants and three people have died as a result of such conflicts. Additionally, 21,468 properties have been damaged between 2015 and 2024, the minister noted.

Features

Electoral reform and abolishing the executive presidency

by Dr Jayampathy Wickramaratne,

President’s Counsel

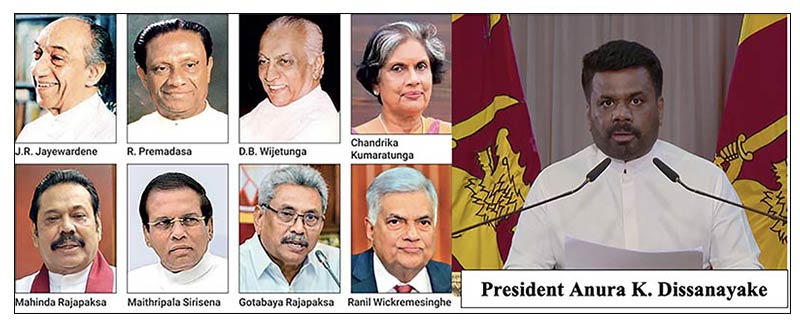

The Sri Lankan Left spearheaded the campaign against introducing the executive presidency and consistently agitated for its abolition. Abolition was a central plank of the platform of the National People’s Power (NPP) at the 2024 presidential elections and of the Janatha Vimukthi Peramuna (JVP) at all previous elections.

Issues under FPP or a mixed system

President Anura Kumara Dissanayake, participating in the ‘Satana’ programme on Sirasa TV, recently reiterated the NPP’s commitment to abolition and raised four issues related to accompanying electoral reform.

The first is that proportional representation (PR) did not, except in a few instances, give the ruling party a clear majority, resulting in a ‘weak parliament’. Therefore, electoral reform is essential when changing to a parliamentary form of government.

Secondly, ensuring that different shades of opinion and communities are proportionally represented may be challenging under the first-past-the-post system (FPP). For example, as the Muslim community in the Kurunegala district is dispersed, a Muslim-majority electorate will be impossible. Under PR, such representation is possible, as happened in 2024, with many Muslims voting for the NPP and its Muslim candidate.

The third issue is a difficulty that might arise under a mixed (FPP-PR) system. For example, the Trincomalee district returned Sinhala, Tamil and Muslim candidates at successive elections. In a mixed system, territorial constituencies would be fewer and ensuring representation would be difficult. For the unversed, there were 160 electorates that returned 168 members under FPP at the 1977 Parliamentary elections.

The fourth is that certain castes may not be represented under a new system. He cited the Galle district where some of the ‘old’ electorates had been created to facilitate such representation.

It might straightaway be said that all four issues raised by President Dissanayake have substantial validity. However, as the writer will endeavour to show, they do not present unsurmountable obstacles.

Proposals for reform, Constitutional Assembly 2016-18

Proposals made by the Steering Committee of the Constitutional Assembly of the 2015 Parliament and views of parties may be referred to.

The Committee proposed a 233-member First Chamber of Parliament elected under a Mixed-Member Proportional (MMP) system that seeks to ensure proportionality in the final allocation of seats. 140 seats (60%) will be filled by FPP. The Delimitation Commission may create dual-member constituencies and smaller constituencies to render possible the representation of communities of interest, whether racial, religious or otherwise. 93 compensatory seats (40%) will be filled to ensure proportionality. Of these, 76 will be filled by PR at the provincial level and 12 by PR at the national level, while the remaining 5 seats will go to the party that secures the highest number of votes nationally.

The Sri Lanka Freedom Party agreed with the proposals in principle, while the Joint Opposition (the precursor of the Sri Lanka Podujana Peramuna) did not make any specific proposals. The Tamil Nationalist Alliance was willing to consider any agreement between the two main parties on the main principles in the interest of reaching an acceptable consensus.

The Jathika Hela Urumaya’s position was interesting. If the presidential powers are to be reduced, the party obtaining the highest number of votes should have a majority of seats. Still, the representation of minor political parties should be assured. Therefore, the number of seats added to the winning party should be at the expense of the party placed second.

The All Ceylon Makkal Congress, Eelam People’s Democratic Party, Sri Lanka Muslim Congress and the Tamil Progressive Alliance jointly proposed that the principles of the existing PR system be retained but with elections being held for 40 to 50 electoral zones and a 2% cut-off point. The Janatha Vimukthi Peramuna was for the abolition of the executive presidency and, interestingly, suggested a mixed electoral system that ensures that the final outcome is proportional.

CDRL proposals

The Collective for Democracy and Rule of Law (CDRL), a group of professionals and academics that included the writer, made detailed proposals on constitutional reform in 2024. It proposed returning to parliamentary government. The legislature would be bicameral, with a House of Representatives of 200 members elected as follows: 130 members will be elected from territorial constituencies, including multi-member and smaller constituencies carved out to facilitate the representation of social groups of shared interest; Sixty members will be elected based on PR at a national or provincial level; Ten seats would be filled through national-level PR from among parties that failed to secure a seat through territorial constituencies or the sixty seats mentioned above, enabling small parties with significant national presence without local concentration to secure representation. Appropriate provisions shall be made to ensure adequate representation of women, youth and underrepresented interest groups.

The writer’s proposal

The people have elected the NPP leader as President and given the party a two-thirds majority in Parliament. It is, therefore, prudent to propose a system that addresses the concerns expressed by the President. Otherwise, we will be going around in circles. The writer believes that the CDRL proposals, suitably modified, present a suitable basis for further discussion.

While the people vehemently oppose any increase in the number of MPs, it would be challenging to address the President’s concerns in a smaller parliament. The writer’s proposal is, therefore, to work within a 225-member Parliament.

The writer proposes that 150 MPs be elected through FPP and 65 through national PR. 10 seats would be filled through national-level PR from among parties that have not secured a seat either through territorial constituencies or the 65 seats mentioned above. The Delimitation Commission shall apportion 150 members among the various provinces proportionally according to the number of registered voters in each province. The Commission will then divide each province into territorial constituencies that will return the number of MPs apportioned. The Commission may create smaller constituencies or multi-member constituencies to render possible the representation of social groups of shared interest.

The 65 PR seats will be proportionally distributed according to the votes received by parties nationally, without a cut-off point. The number of ‘PR MPs’ that a party gets will be apportioned among the various provinces in proportion to the votes received in the provinces. For example, if Party A is entitled to 10 PR seats and has obtained 20% of its total vote from the Central Province, it will fill 2 PR seats from candidates from that Province, and so on. Each party shall submit names of potential ‘PR MPs’ from each of the provinces where the party contests at least one constituency in the order of its preference, and seats allotted to that party in a given province are filled accordingly. The remaining 10 seats will be filled by small parties as proposed by the CDRL.

How does the proposed system address President Dissanayake’s concerns?

The President’s concern that PR will result in a weak parliament is sufficiently addressed when a majority of MPs are elected under FPP.

Before dealing with the other three issues, it must be said that voters do not always vote for candidates from their communities. A classic example is the 1965 election result in Balapitiya, a Left-oriented constituency dominated by a particular caste. The Lanka Sama Samaja Party boldly nominated L.C. de Silva, from a different caste, to contest Lakshman de Silva, a long-standing MP who crossed over to bring down the SLFP-LSSP coalition. Balapitiya voters punished Lakshman and elected L.C.

Multi-member constituencies have generally served their purpose but not always. The Batticaloa dual-member constituency had been created to ‘render possible’ the election of a Tamil and a Muslim. At the 1970 elections, the four leading candidates were Rajadurai of the Federal Party, Makan Markar of the UNP, Rahuman of the SLFP and the independent Selvanayagam. The Muslim vote was closely split between Macan Markar and Rahuman, resulting in both losing. Muslim voters surely knew that a split might deny Muslim representation but preferred to vote according to their political convictions.

The President’s second concern that a dispersed community may not get representation under FPP will also be addressed better under the proposed system. Taking the same Kurunegala district as an example, a party could attract Muslim voters by placing a Muslim high up on the PR list. Similarly, a Tamil party could place a candidate from a depressed community high up in its Northern Province PR list to attract voters of depressed communities and ensure their representation.

The third concern was that the number of electorates would be less under a mixed system, making it challenging to carve out electorates to facilitate the representation of communities, the Trincomalee district being an example. Empowering the Delimitation Commission to create smaller electorates assuages this concern. It will not be Trincomalee District but the whole Eastern Province to which a certain number of FPP MPs will be allotted, giving the Commission broad discretion to carve out electorates. The Commission could also create multimember constituencies to render possible the representation of communities of interest. The fourth concern about caste representation would also be addressed similarly.

It may be noted that the difference between the number of FPP MPs (150) under the proposed system is only 10% less than that under the delimitation of 1975 (168). Also, there will be no cut-off point for PR as against the present cut-off of 5%. This will help small as well as not-so-small parties. Reserving 10 seats for small parties also helps address the concerns of the President.

No spoilers, please. Don’t let electoral reform be an excuse for a Nokerena Wedakama

The writer submits the above proposals as a basis for discussion. While a stable government and the representation of various interests are essential, abolishing the dreaded Executive Presidency is equally important. These are not mutually exclusive.

President Dissanayake also said on Sirasa TV that once the local elections are over, the NPP would first discuss the issue internally. This is welcome as there would be a government position, which can be the basis for further discussion.

This is the first time a single political party committed to abolition has won a two-thirds majority. Another such opportunity will almost certainly not come. Let there be no spoilers from either side. Let electoral reform not be an excuse for retaining the Executive Presidency. Let the Sinhala saying ‘nokerena veda kamata konduru thel hath pattayakuth thava tikakuth onalu’ not apply to this exercise (‘for the doctoring that will never come off, seven measures and a little more, of the oil of eye-flies are required’—translation by John M. Senaveratne, Dictionary of Proverbs of the Sinhalese, 1936).

According to recent determinations of the Supreme Court, a change to a parliamentary form of government requires the People’s approval at a referendum. While the NPP has a two-thirds majority, it should not take for granted a victory at a referendum held late in the term of Parliament for, then, there is the danger of a referendum becoming a referendum on the government’s performance rather than one on the constitutional bill, with opposition parties playing spoilers. If the government wishes to have the present form of government for, say, four years, it could now move a bill for abolition with a sunset clause that provides for abolition on a specified date. Delay will undoubtedly frustrate the process and open the government to the accusation that it indulged in a ‘nokerena vedakama’.

Features

Did Rani miss manorani ?

(A film that avoids the ‘Mannerism’ of a Biopic: Rani)

by Bhagya Rajapakshe

bhagya8282@gmail.com

This is only how Manorani sees Richard. It doesn’t have a lot of what Richard did. Although Manorani is not someone who pays attention to the happenings in the country. It was only after her son was kidnapped that she began to feel that this was happening in the country.She had human emotions. But she was a person who smoked cigarettes and drank whiskey and lived a merry life.”

(Interview with “Rani” film director Ashoka Handagama by Upali Amarasinghe – 02.02.2025 ‘Anidda’ weekend newspaper, pages 15 and 19)

The above statement shows the key attitude of the director of the movie, “Rani” towards the central character of the film, Dr. Manorani Sarawanamuttu. This statement is highly controversial. Similarly, the statement given by the director to Groundviews on 30.01.2025 about capturing the depth of Rani’s character shows that he has done so superficially, frivolously?

A biopic is a specific genre of cinema. This genre presents true events in the life of a person (a biography), or a group of people who are currently alive or who belong to history with recognisable names. The biopic genre often artistically and cinematically explores keenly the main character along with a few secondary characters connected to the central figure. World cinema is proof that even if the characters are centuries old, they are carefully researched and skilled directors take care to weave the biographies into their films without causing any harm or injustice to the original character.

According to the available authentic reports, Manorani Saravanamuthu was a professionally responsible medical doctor. Chandri Peiris, a close friend of her family, in his feature article on Manorani in the ‘Daily Mirror’ newspaper on 06th November 2021, says this about her:

“She was a doctor who had her surgeries in the poorest areas around Colombo which made her popular with communities who preferred their women to be seen by female doctors. She had a wonderful manner with her patients which my mother described by saying, ‘looking at her is enough to make you well …. When it came to our outlandish group of friends, she was always there to steer many of us through some very personal issues such as: unplanned pregnancies, teenage pregnancies, mental breakdowns, STD’s, young lovers who ran away and married, depression, circumcisions, break-ups, fractures, dance injuries, laryngitis (especially among the actors and singers) fevers, pimples, and even the odd boil on the bum.”

But the image of Rani depicted by Handagama in his film is completely different from this. According to the film, a major feature of her life consisted of drinking whiskey and smoking cigarettes. Her true role is unspoken, hidden in the film. A grave question arises as to whether the director spent adequate time doing the research? to find out who Manorani really was. In his article Chandri Peiris further says the following about Manorani:

“Soon after the race riots in 1983, Manorani (along with Richard) helped a great many Sri Lankan Tamils to find refuge in countries all over the world. Nobody knew about this. But all of us who used to hang around their house kept seeing unfamiliar people come over to stay a few days and then leave. Among them were the three sons of the Master-in-Charge of Drama at S. Thomas’ College, who were swiftly sent abroad by the tireless efforts of this mother and son. It was then that we worked out that their home was a safehouse. … Manorani was vehemently opposed to the terror wreaked by the LTTE and always wanted Sri Lanka to be one country that was home to the many diverse cultures within it. When the ethnic strife developed into a full-on war with those who wanted to create a separate state for Tamil Eelam, she remained completely against it.”

According to the director of the film, if Rani had no awareness of what was happening in the country and the world, how could she have helped the victims survive and leave the country during that life-threatening period? It is clear from all this that the director has failed to fully study the character of Manorani and what she did. There is a scene where Manorani watches a Sinhala stage play with much annoyance and on her way back home with Richard, she is shown insensitively avoiding Richard’s friend Gayan being assaulted by a mob. This demeanour does not match the actual reports and information published about Manorani. How did the director miss these records? It shows his indifference to researching background information for a film such as this. He clearly does not think that research is essential for a sharp-witted artist in creating his artwork. In his own words, he told the Anidda newspaper:

“But the information related to this is in the public domain and the challenge I had was to interpret that information in the way I wanted. I am not an investigative journalist; My job is to create a work of art. That difference should be understood and made.”

And according to the director, “I was invited to do the film in 2023. The script was written within two to three months and the shooting was planned quickly.” Thus, it is clear that there has been no time to study the inner details related to Manorani, the main character of the film, or the character’s Mannerism. Professor Sarath Chandrajeewa, who published a book with two critical reviews on Handagama’s previous film ‘Alborada’, emphasises in both, that ‘Alborada’ also became weak due to the lack of proper research work’ (Lamentation of the Dawn (2022), pages 46-57).

Directors working in the biopic genre with a degree of seriousness consider it their responsibility to study deeply and construct the ‘mannerism’ of such central characters to create a superior biographical film. For example, in Kabir Khan’s 2021 film ’83’ the actor Tahir Raj Bhasin, who played the role of Sunil Gavaskar, said that it took him six months to study Sunil Gavaskar’s unique style characteristics or Mannerism.

Also, Austin Butler, the actor who played the role of Elvis Presley in the movie ‘Elvis’ directed by Buz Luhrmann and released in 2022, said in a news conference: After he started studying the character of Elvis, he became obsessed with the character, without meeting or talking to his family for nearly one year, while making the film in Australia before, during Covid and after.

‘Oppenheimer’ (2023) was written and directed by Christopher Nolan, in which Cillian Murphy plays the role of Oppenheimer. Nolan read and studied the 700-page story about Oppenheimer called ‘American Prometheus’ . It is said that it took three months to write the script and 57 days for shooting, and finally a two-hour film was created. The rejection of such intense studies by our filmmakers will determine the future of cinema in this country.

Acting is the prime aspect of a movie. The character of Manorani is performed very skillfully in the movie. But certain of her characteristics and mannerism become repetitive and in their very repetitiveness become tiresome to watch. For example, right across the film Manorani is shown smoking, drinking alcohol, sitting and thinking, going towards a window and thinking and smoking again. It would have been better if it had been edited. The audience is thereby given the impression that Manorani lives on cigarettes and whiskey. Although smoking and drinking alcohol is a common practice among some women of Manorani’s social class, it is depicted in the film so repetitively that it creates a sense of revulsion in the viewer. In the absence of close-ups and a play of light and dark, Manorani’s mental states cannot be seen in their intense three dimensionality. It is a question whether the director gave up directing and let the actress play the role of Manorani as she wished. At the beginning of the film, close-ups of Manorani appear with the titles but gradually become normal camera angles in the film. This avoids the use of close-ups of Manorani’s face to show emotion in the most shocking moments in the film. Below are some films that demonstrate this cinematic technique well.

‘Three Colours: Blue’ (1993) French, Directed by Kryzysztof Kies’lowski.

‘Memories in March’

(2010) Indian, Directed by Sanjoy Nag.

‘Manchester by the Sea’

(2016) English, Directed by Keneth Lonergan.

‘Collateral Beauty’

2016) English, Directed by David Frankel.

Certain characters appear in the film without any contribution to building Manorani’s role. Certain scenes such as the Television news, bomb explosions, dialogue scenes where certain characters interview Manorani are not integrated into the film’s narrative and feel forced. The scene with the group of hooligans in a jeep at the end of the film is like a strange tail to the film.

Richard’s sexual orientation, which is hinted at the end of the film by these thugs in the final scene, is an insult to him. It is a great disrespect to those characters to present facts without strong information analysis and to tell the inner life of those characters while presenting a real character through an artwork with real names. The director should not have done such humour and humiliation.

There is some thrill in seeing actors who resemble the main political personalities of that era playing those roles in the film. In this the film has more of a documentary than a fictional quality but it barely marks the socio-political history of this country during the period of terror in 88-89. The character of Manorani was created as a person floating in that history ungrounded, without a sense of gravity.

The film’s music and vocals are mesmerising. But unfortunately, the song ‘Puthune’ (Dearest Son), which has a very strong lyrical composition, melody and singing, is placed at the end of the film, so the audience does not know its strength. This is because the audience starts to leave the cinema as soon as the song starts, when the closing credits scrolled down. If the song had accompanied the scene on the beach where we see Manorani for the last time, the audience would have felt its strength.

Manorani’s true personality was a unique blend of charm, sensitivity, compassion, intelligence, warmth and fun, which enhanced her overall beauty, as evidenced by various written accounts of her. Art critics and historians H. W. Johnson and Anthony F. A Johnson state in their book ‘History of Art’ (2001), “Every work of art tells whether it is artistic or not. And the grammar and structure of the form will signal to us that.”

-

Business5 days ago

Business5 days agoSri Lanka’s 1st Culinary Studio opened by The Hungryislander

-

Sports6 days ago

Sports6 days agoHow Sri Lanka fumbled their Champions Trophy spot

-

Features6 days ago

Features6 days agoThe Murder of a Journalist

-

Sports6 days ago

Sports6 days agoMahinda earn long awaited Tier ‘A’ promotion

-

Features6 days ago

Features6 days agoExcellent Budget by AKD, NPP Inexperience is the Government’s Enemy

-

Sports5 days ago

Sports5 days agoAir Force Rugby on the path to its glorious past

-

Features5 days ago

Features5 days agoRani’s struggle and plight of many mothers

-

News6 days ago

News6 days agoSri Lanka’s first ever “Water Battery”