Features

Rice Genetic Improvement Odyssey of Past Centuries

by M. P. Dhanapala

Former Director, Rice Research and Development Institute, Batalagoda

Email: maddumadhanapala@yahoo.com

History is important. It keeps you away from reinventing the wheel and repeating the mistakes already committed in the past. In history, there should not be hidden expressions to read between lines as “the ten giants of King Dutugamunu were fed with traditional rice,”concealing the details of what the others were eating and why they were not giants or that “we have been exporting rice during the past in such and such era” without disclosing the quantities and the recipient countries. For that matter if you go through the export details, we do export rice even now.

The green revolution was criticized as the contributing factor for the so called unidentified Kidney Disease of Unknown Origin (CKDu) which was reported primarily from the North Central Province. Whatever the causal factor of CKDu is, Norman Borlaug or his green revolution has nothing to do with the kidney disease or rice in Sri Lanka. It is true that his innovative ideology in wheat breeding induced the rice breeders worldwide to develop a physiologically efficient rice plant type by changing the plant stature and canopy characteristics. The Sri Lankan rice varieties were developed within the country, by the Sri Lankan scientists. It was an extension of the breeding process initiated by the British scientists during the colonial era. The progress of rice breeding from its inception by different generations will be unfolded in this write-up to judge the calculated decisions taken by the ancestral breeders to improve rice productivity in the country.

I would like to lay the baseline from a report published by Edward Elliott, a British Civil Servant in 1913. (Tropical Agriculturist, Vol. XLI, No. 6, Dec. 1913). He states that the forced labor (Rajakariya) that existed then was abolished in 1832. Subsequently, the communal cooperation system (Atththam) also ceased to exist gradually. These two incidents were cited as the major reasons for the neglect of irrigation structures and subsequent decline of rice production in the mid 19th Century. The annual rice production estimated for the period of 10 years ending in 1856 was 5.5 million bushels, the lowest in the recorded history.

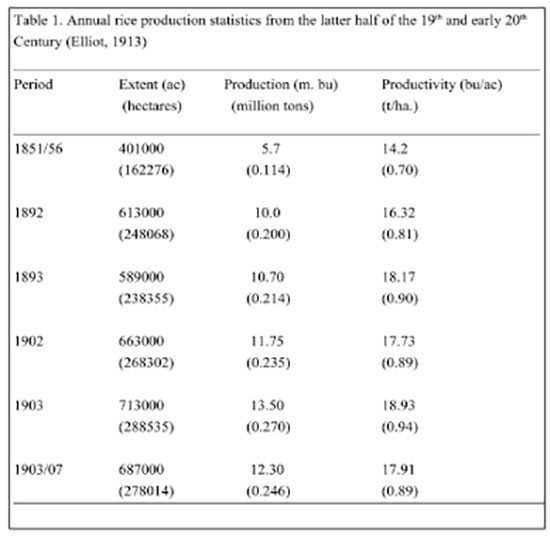

Enacting the Paddy Ordinance in 1857 allowed voluntary restoration of old irrigation structures which eventually led to the gradual increase in the cultivated extent and the annual rice production. Estimated rice production data during this era and at the turn of the century are summarized in Table 1. The original data were in acres and bushels. The data were transformed into hectares and kilograms and tonnes assuming 20 kg as the bushel weight. The transformed data in Table 1 appear within parentheses.

See table 1.

Annual rice production statistics from the latter half of the 19th and early 20th Century (Elliot, 1913)

The rice production data above are estimates based on returns from paddy, probably grain tax, in the Government Blue Books. You may realize that these estimates are sometimes too high when actual data appear towards 1940s. However, at the turn of the 19th Century, the rice varieties were exclusively traditional types maintained by farmers and the Department of Agriculture was not established.

Many critics maintain that we had innumerable different varieties of rice in the past. The earliest recorded in the history was a collection of 300 rice varieties displayed by Nugawela Dissawe for the agri-horticultural exhibition held in 1902 (Molegoda, 1924) (Trop. Agric. XLII (4): 218-224.). This probably represented almost all the cultivars in the field during this period. This was the largest collection of rice varieties in the recorded history in Ceylon, leaving out the recent collections performed in the latter half of the 20th century. Molegoda explains very comprehensively the status of rice varieties and the procedure followed in naming them.

The rice cultivation at the beginning of 20th century was entirely organic manure dependent. The farmers then were apparently more competent in traditional methods of rice cultivation. The most striking feature during this era was that the average yields were below one ton/ha (<20 bu/ac) even in the best productive year, 1903 (Table 1).

In 1914, an encouraging note on Extension of Paddy Cultivation by A. W. Beven (Trop. Agric. XLIII (6): 421-424.) appears with the suggestion of seed selection to improve rice yields. He states that in the year 1913 the yield estimate of 9,622,320 bushels was too high a target, i.e.14.2 bu/ac (0.71 t/ha), for the cultivated extent of 671,711ac (271,827ha), but suggests that with seed selection accompanied by proper land preparation, manuring and transplanting, the yields could be increased up to 25 bu/ac (1.25t/ha). This suggestion was at the inception of the Department of Agriculture which was established in 1912.

The earliest record on rice varietal improvement dates back to seed selection in 1914 by Dr. Lock at Peradeniya. This was done more or less parallel with the establishment of Johannsen’s pure line theory (1903). In the literature, Dr. Lock’s improved Hatial (a seven month variety) appears from time to time as a standard variety in yield tests.

The next most important step was the pure-line selection. Initially, three Economic Botanists, F. Summers (1921), R.O. Iliffe (1922), L. Lord (1927) and at latter stages Paddy Officer G.V. Wickremasekera were involved in the selection of pure- lines (Trop. Agric. LVIII (2): 67-70; Trop. Agric. LXVIII (5): 309-318). Pure-line selection exploited heterogeneity within the farmer maintained traditional rice cultivars. Each cultivar composed of different types within it. As a result, individual plant selection within cultivars produced progenies with better genetic potential, but resembling the mother plant selected; they bred true to type as rice is an obligate inbreeder. This was the essence of pure-line theory established by Johannsen (1903).

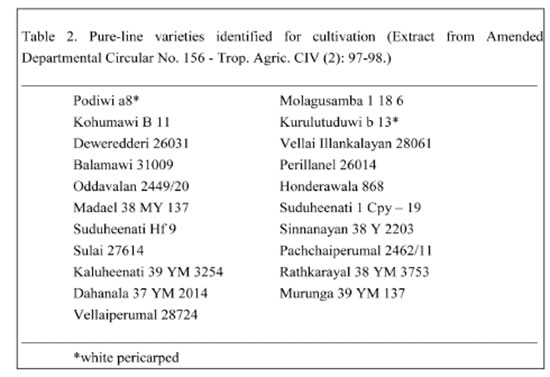

Pure-line selection was initiated with a representative collection of traditional varieties. The most popular varieties were included in the process. Pure-line selection was done at two major locations, Mahailluppallama and Peradeniya. Subsequently, selection was regionalized to accommodate regionally adapted varieties in the process. The best isolated progenies were tested at 19 test locations in different agro-ecological regions for adaptability, prior to recommendation. The best adapted pure-lines (21 lines – Table 2) were identified for purity maintenance at four different paddy stations – Ambalantota (nine lines), Mahailluppallama (eight lines), Madampe (two lines) and Batalagoda (two lines). Further multiplication of seeds was done in government farms under the supervision of Agricultural Officers and distributed as seed paddy for cultivation (Trop. Agric. CIV (2): 97-98.).

See table 2.

Pure-line varieties identified for cultivation (Extract from Amended Departmental Circular No. 156 – Trop. Agric. CIV (2): 97-98.)

While the pure-line selection process was on, Joachim (1927) (Trop. Agric. LXIX 137) warned that the sustenance of increased yields by cultivation of high yielding pure-lines has to be met with liberal manuring. However, despite of all these attempts during the two decades from 1920s, the paddy yields were not substantially increased (Table 3). Rice yield data presented in Table 3 shows lower values compared to yield estimates from Government Blue Books presented in Table 1. The data in Table 3 being more reliable, the Table 1 data could be overestimates.

However, the majority of the harvested rice crop in the 1940s could be from potentially better pure-line selections, but the yields were much below the anticipated levels. The total production was around 15 million bushels (0.3 m tons) and yields stagnated at around 14 bu/ac (0.7 t/ha).

The Draft Scheme for Development of the Paddy Industry in Ceylon drawn in 1945 (Trop. Agric. CI (3) 191-195) begins with the statement that only a third of the annual requirement is met by the local rice production.

The balance was imported; the population was less than seven million during that period and the paddy cultivation was done organically with the best adapted pure-lines of traditional cultivars, though it failed to deliver what was intended.

The importance of inorganic (chemical) fertilizer was felt during this period as the only option to improve paddy yields further. Use of sodium nitrate (Na NO3) as the source of nitrogen (N) was attempted in rice prior to 1905 based on American experience in soybean cultivation, but nitrite (NO2–) toxicity under reduced conditions in submerged paddy soils prohibited its use. Superiority of NH4 form of N was demonstrated by Nagaoka (1905) and Daikuhara and Imaseki (1907). However, the application of N promoted vegetative growth in pure-lines derived from traditional rice varieties causing premature lodging. Furthermore, two fungal diseases, blast and brown spot, became prominent. Around this period some introduced varieties were tested without much success. Among them, Ptb 16 from Pathambi, India, popularly called Riyan wee, with long panicles and slender grains (Buriyani rice) became popular, but self sufficiency in rice appeared to be far away.

Transition to another phase in rice breeding began as the rice breeders over the world employed cross-bred populations to create genetic variability to bring together desirable characteristics of different rice cultivars to develop better varieties. Rice hybridization techniques were developed around early 1920s and a major break through in changing the plant-type was accomplished in Japan with the use of Jikkoku, a dwarf natural mutant of Japonica rice. The performance of Japonica varieties exhibited substantial improvement with this transition. Influenced by the Japanese experience, the Food and Agriculture Organization sponsored a cross breeding program of Japonica with Indica rices in Cuttak, India to change the Indica plant type too in this direction, but without success due to incompatibility between the two groups (Japonica and Indica) leading to grain sterility in subsequent generations.

In Sri Lanka, the first paper on rice hybridization techniques was published in 1951 by J.J. Niles, an assistant in Economic Botany, guided by Prof. M. F. Chandraratne, the Economic Botanist (Trop. Agric. CVII (1):25-29.). Prof. Chandraratne was instrumental in initiation of rice hybridization. Simultaneously rice hybridization work began at the Dry Zone Agricultural Research Station at Mahailluppallama under the guidance of Dr. Ernest Abeyratne. The Central Rice Breeding Station, Batalagoda was established in 1952 and Dr. H. Weeraratne was transferred from Mahailluppallama to Batalagoda as the rice breeder with the hybrid populations already developed at Mahailluppallama.

Dr. Weeraratne, influenced by his superiors, Prof. Chandraratne and Dr. Abeyratne, continued rice hybridization to create genetic variability for selection. The hybridization techniques adopted by him were published in 1954 (Trop. Agric. CX (2) 93-97). Apparently, the labor intensive pedigree method was employed by Dr. Weeraratne to identify and fix desirable genotypes from segregating populations. And this was the beginning of the “H” series of varieties that revolutionized the rice sector in Sri Lanka. The letter “H” was used to imply that the varieties were of hybrid origin and were different from traditional varieties or pure-lines, but not to imply that they are hybrids.

Fig. 1,

The Central Rice Breeding Station, Batalagoda, Department of Agriculture

The first of the series, H4 (4.5 month, red bold), released in 1957, reached its peak popularity after a five year lapse of time and covered over 60% of the cultivated extent in Maha season, 62/63. The others in the series were H7 (3.5 month, white bold), H8 (4.5 month, white samba), H9 (5-6 month, white bold), H10 (3 month, red bold). Release of H varieties (1) minimized crop losses due to blast disease, (2) changed rice cropping pattern from single to double cropping, (3) use of N fertilizer increased by 350% due to their moderate response to fertilizer, (4) increased national yield level up to 3.5 t/ha (Senadhira et. al., Rice Symposium, Department of Agriculture, 1980). This effort, though appreciated widely, fell short of self sufficiency again.

The most controversial phase for the critics in rice breeding was initiated in mid 1960s, while “H” varieties were replacing the pure-lines and the traditional varieties from paddy fields. The International Rice Research Institute was established in 1960 and the plant physiologists conceptualized the plant type structure of rice to make it physiologically efficient. The development of “H” varieties (Old Improved Varieties) abruptly ended with these new innovations.

The breeders responsible for developing this new plant type in Sri Lanka, specifically the Bg varieties, were Dr. H. Weeraratne, Dr. N. Vignarajah, Dr. D. Senadhira and Mr. C.A. Sandanayake. None of them are among us any more. I joined the team in the late 1960s, at the tail end of H varieties and continued the process till the country reached the brim of self reliance in rice.

The Bg and other modern varieties are physiologically efficient. They are devoid of unproductive plant tissues and ineffective tillers. The plant structure is designed to reduce mutual shading of leaves and trap solar radiation effectively by every leaf in the canopy thus reducing the respiratory losses and promoting the net assimilation rate. They out yield traditional and H varieties at any level of soil fertility and show positive grain yield response to added fertilizer. They are lodging resistant and incorporated with resistance/tolerance to major pests and diseases prevalent in the country. More preciously, we have reversed the source-sink relationship of the rice plant to translocate photosynthates to produce more grains and less straw. The potential yield of improved varieties exceeds 6t/ha. All these traits listed above have been tested in controlled experiments in the field to confirm the superiority of new improved varieties. We reap around 4.5 tons/ha as our national average yield at present; the country is self sufficient in rice, the dream every political leader had since independence.

This in a nut shell is what the rice breeders have accomplished and for which they were given the title “Kumbandayas” in an article written apparently by a medical professional. The local rice scientists embark only on innovations backed by scientific facts. They do not have to exaggerate or lie. They know little more than those who seek cheap popularity by being critical about the accomplishments of rice scientists. This country needs people dedicated and confined to their respective professions allowing other professionals to play their own role. At any time rice breeders can take the country back to the traditional rice era if you want to begin all over again from the beginning. The traditional accessions are in long-term storage at the Plant Genetic Resource Center (PGRC), Gannoruwa, Department of Agriculture, and can be taken out for multiplication at any time as the seed samples are viable.

Now I repent why we produced rice with more grains and less straw. There appears to be unsatisfied demand for straw. I like to conclude this disclosure with a statement made by Dr. N. M. Perera at the University of Ceylon, Peradeniya in the mid 1960s. “Comrade, I can give you facts and figures, but I am sorry; I am unable to implant a brain in you”.

(The writer holds a Ph D, Genetics and Plant Breeding, North Dakota University, USA, 1990, M Sc., Plant Breeding, Saga University, Japan, 1978 and B sc. Agric. University of Ceylon, Sri-Lanka, 1968. He has served as Research Officer, Rice Breeding (1969 – 1995) Central Rice Breeding Station, Batalagoda, Director, Rice Research and Development Institute, (1996 – 2000), Batalagoda, Affiliate Scientist, International Rice Research Institute (2000 – 2003), Philippines and Technical Advisor, JICA,, Tsukuba International Center, (2004 – 2012), Japan)

Features

Challenges faced by the media in South Asia in fostering regionalism

SAARC or the South Asian Association for Regional Cooperation has been declared ‘dead’ by some sections in South Asia and the idea seems to be catching on. Over the years the evidence seems to have been building that this is so, but a matter that requires thorough probing is whether the media in South Asia, given the vital part it could play in fostering regional amity, has had a role too in bringing about SAARC’s apparent demise.

SAARC or the South Asian Association for Regional Cooperation has been declared ‘dead’ by some sections in South Asia and the idea seems to be catching on. Over the years the evidence seems to have been building that this is so, but a matter that requires thorough probing is whether the media in South Asia, given the vital part it could play in fostering regional amity, has had a role too in bringing about SAARC’s apparent demise.

That South Asian governments have had a hand in the ‘SAARC debacle’ is plain to see. For example, it is beyond doubt that the India-Pakistan rivalry has invariably got in the way, particularly over the past 15 years or thereabouts, of the Indian and Pakistani governments sitting at the negotiating table and in a spirit of reconciliation resolving the vexatious issues growing out of the SAARC exercise. The inaction had a paralyzing effect on the organization.

Unfortunately the rest of South Asian governments too have not seen it to be in the collective interest of the region to explore ways of jump-starting the SAARC process and sustaining it. That is, a lack of statesmanship on the part of the SAARC Eight is clearly in evidence. Narrow national interests have been allowed to hijack and derail the cooperative process that ought to be at the heart of the SAARC initiative.

However, a dimension that has hitherto gone comparatively unaddressed is the largely negative role sections of the media in the SAARC region could play in debilitating regional cooperation and amity. We had some thought-provoking ‘takes’ on this question recently from Roman Gautam, the editor of ‘Himal Southasian’.

Gautam was delivering the third of talks on February 2nd in the RCSS Strategic Dialogue Series under the aegis of the Regional Centre for Strategic Studies, Colombo, at the latter’s conference hall. The forum was ably presided over by RCSS Executive Director and Ambassador (Retd.) Ravinatha Aryasinha who, among other things, ensured lively participation on the part of the attendees at the Q&A which followed the main presentation. The talk was titled, ‘Where does the media stand in connecting (or dividing) Southasia?’.

Gautam singled out those sections of the Indian media that are tamely subservient to Indian governments, including those that are professedly independent, for the glaring lack of, among other things, regionalism or collective amity within South Asia. These sections of the media, it was pointed out, pander easily to the narratives framed by the Indian centre on developments in the region and fall easy prey, as it were, to the nationalist forces that are supportive of the latter. Consequently, divisive forces within the region receive a boost which is hugely detrimental to regional cooperation.

Two cases in point, Gautam pointed out, were the recent political upheavals in Nepal and Bangladesh. In each of these cases stray opinions favorable to India voiced by a few participants in the relevant protests were clung on to by sections of the Indian media covering these trouble spots. In the case of Nepal, to consider one example, a young protester’s single comment to the effect that Nepal too needed a firm leader like Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi was seized upon by the Indian media and fed to audiences at home in a sensational, exaggerated fashion. No effort was made by the Indian media to canvass more opinions on this matter or to extensively research the issue.

In the case of Bangladesh, widely held rumours that the Hindus in the country were being hunted and killed, pogrom fashion, and that the crisis was all about this was propagated by the relevant sections of the Indian media. This was a clear pandering to religious extremist sentiment in India. Once again, essentially hearsay stories were given prominence with hardly any effort at understanding what the crisis was really all about. There is no doubt that anti-Muslim sentiment in India would have been further fueled.

Gautam was of the view that, in the main, it is fear of victimization of the relevant sections of the media by the Indian centre and anxiety over financial reprisals and like punitive measures by the latter that prompted the media to frame their narratives in these terms. It is important to keep in mind these ‘structures’ within which the Indian media works, we were told. The issue in other words, is a question of the media completely subjugating themselves to the ruling powers.

Basically, the need for financial survival on the part of the Indian media, it was pointed out, prompted it to subscribe to the prejudices and partialities of the Indian centre. A failure to abide by the official line could spell financial ruin for the media.

A principal question that occurred to this columnist was whether the ‘Indian media’ referred to by Gautam referred to the totality of the Indian media or whether he had in mind some divisive, chauvinistic and narrow-based elements within it. If the latter is the case it would not be fair to generalize one’s comments to cover the entirety of the Indian media. Nevertheless, it is a matter for further research.

However, an overall point made by the speaker that as a result of the above referred to negative media practices South Asian regionalism has suffered badly needs to be taken. Certainly, as matters stand currently, there is a very real information gap about South Asian realities among South Asian publics and harmful media practices account considerably for such ignorance which gets in the way of South Asian cooperation and amity.

Moreover, divisive, chauvinistic media are widespread and active in South Asia. Sri Lanka has a fair share of this species of media and the latter are not doing the country any good, leave alone the region. All in all, the democratic spirit has gone well into decline all over the region.

The above is a huge problem that needs to be managed reflectively by democratic rulers and their allied publics in South Asia and the region’s more enlightened media could play a constructive role in taking up this challenge. The latter need to take the initiative to come together and deliberate on the questions at hand. To succeed in such efforts they do not need the backing of governments. What is of paramount importance is the vision and grit to go the extra mile.

Features

When the Wetland spoke after dusk

By Ifham Nizam

As the sun softened over Colombo and the city’s familiar noise began to loosen its grip, the Beddagana Wetland Park prepared for its quieter hour — the hour when wetlands speak in their own language.

World Wetlands Day was marked a little early this year, but time felt irrelevant at Beddagana. Nature lovers, students, scientists and seekers gathered not for a ceremony, but for listening. Partnering with Park authorities, Dilmah Conservation opened the wetland as a living classroom, inviting more than a 100 participants to step gently into an ecosystem that survives — and protects — a capital city.

Wetlands, it became clear, are not places of stillness. They are places of conversation.

Beyond the surface

In daylight, Beddagana appears serene — open water stitched with reeds, dragonflies hovering above green mirrors.

Yet beneath the surface lies an intricate architecture of life. Wetlands are not defined by water alone, but by relationships: fungi breaking down matter, insects pollinating and feeding, amphibians calling across seasons, birds nesting and mammals moving quietly between shadows.

Participants learned this not through lectures alone, but through touch, sound and careful observation. Simple water testing kits revealed the chemistry of urban survival. Camera traps hinted at lives lived mostly unseen.

Demonstrations of mist netting and cage trapping unfolded with care, revealing how science approaches nature not as an intruder, but as a listener.

Again and again, the lesson returned: nothing here exists in isolation.

Learning to listen

Perhaps the most profound discovery of the day was sound.

Wetlands speak constantly, but human ears are rarely tuned to their frequency. Researchers guided participants through the wetland’s soundscape — teaching them to recognise the rhythms of frogs, the punctuation of insects, the layered calls of birds settling for night.

Then came the inaudible made audible. Bat detectors translated ultrasonic echolocation into sound, turning invisible flight into pulses and clicks. Faces lit up with surprise. The air, once assumed empty, was suddenly full.

It was a moment of humility — proof that much of nature’s story unfolds beyond human perception.

Sethil on camera trapping

The city’s quiet protectors

Environmental researcher Narmadha Dangampola offered an image that lingered long after her words ended. Wetlands, she said, are like kidneys.

“They filter, cleanse and regulate,” she explained. “They protect the body of the city.”

Her analogy felt especially fitting at Beddagana, where concrete edges meet wild water.

She shared a rare confirmation: the Collared Scops Owl, unseen here for eight years, has returned — a fragile signal that when habitats are protected, life remembers the way back.

Small lives, large meanings

Professor Shaminda Fernando turned attention to creatures rarely celebrated. Small mammals — shy, fast, easily overlooked — are among the wetland’s most honest messengers.

Using Sherman traps, he demonstrated how scientists read these animals for clues: changes in numbers, movements, health.

In fragmented urban landscapes, small mammals speak early, he said. They warn before silence arrives.

Their presence, he reminded participants, is not incidental. It is evidence of balance.

Narmadha on water testing pH level

Wings in the dark

As twilight thickened, Dr. Tharaka Kusuminda introduced mist netting — fine, almost invisible nets used in bat research.

He spoke firmly about ethics and care, reminding all present that knowledge must never come at the cost of harm.

Bats, he said, are guardians of the night: pollinators, seed dispersers, controllers of insects. Misunderstood, often feared, yet indispensable.

“Handle them wrongly,” he cautioned, “and we lose more than data. We lose trust — between science and life.”

The missing voice

One of the evening’s quiet revelations came from Sanoj Wijayasekara, who spoke not of what is known, but of what is absent.

In other parts of the region — in India and beyond — researchers have recorded female frogs calling during reproduction. In Sri Lanka, no such call has yet been documented.

The silence, he suggested, may not be biological. It may be human.

“Perhaps we have not listened long enough,” he reflected.

The wetland, suddenly, felt like an unfinished manuscript — its pages alive with sound, waiting for patience rather than haste.

The overlooked brilliance of moths

Night drew moths into the light, and with them, a lesson from Nuwan Chathuranga. Moths, he said, are underestimated archivists of environmental change. Their diversity reveals air quality, plant health, climate shifts.

As wings brushed the darkness, it became clear that beauty often arrives quietly, without invitation.

Sanoj on female frogs

Coexisting with the wild

Ashan Thudugala spoke of coexistence — a word often used, rarely practiced. Living alongside wildlife, he said, begins with understanding, not fear.

From there, Sethil Muhandiram widened the lens, speaking of Sri Lanka’s apex predator. Leopards, identified by their unique rosette patterns, are studied not to dominate, but to understand.

Science, he showed, is an act of respect.

Even in a wetland without leopards, the message held: knowledge is how coexistence survives.

When night takes over

Then came the walk: As the city dimmed, Beddagana brightened. Fireflies stitched light into darkness. Frogs called across water. Fish moved beneath reflections. Insects swarmed gently, insistently. Camera traps blinked. Acoustic monitors listened patiently.

Those walking felt it — the sense that the wetland was no longer being observed, but revealed.

For many, it was the first time nature did not feel distant.

Faunal diversity at the Beddagana Wetland Park

A global distinction, a local duty

Beddagana stands at the heart of a larger truth. Because of this wetland and the wider network around it, Colombo is the first capital city in the world recognised as a Ramsar Wetland City.

It is an honour that carries obligation. Urban wetlands are fragile. They disappear quietly. Their loss is often noticed only when floods arrive, water turns toxic, or silence settles where sound once lived.

Commitment in action

For Dilmah Conservation, this night was not symbolic.

Speaking on behalf of the organisation, Rishan Sampath said conservation must move beyond intention into experience.

“People protect what they understand,” he said. “And they understand what they experience.”

The Beddagana initiative, he noted, is part of a larger effort to place science, education and community at the centre of conservation.

Listening forward

As participants left — students from Colombo, Moratuwa and Sabaragamuwa universities, school environmental groups, citizens newly attentive — the wetland remained.

It filtered water. It cooled air. It held life.

World Wetlands Day passed quietly. But at Beddagana, something remained louder than celebration — a reminder that in the heart of the city, nature is still speaking.

The question is no longer whether wetlands matter.

It is whether we are finally listening.

Features

Cuteefly … for your Valentine

Valentine’s Day is all about spreading love and appreciation, and it is a mega scene on 14th February.

Valentine’s Day is all about spreading love and appreciation, and it is a mega scene on 14th February.

People usually shower their loved ones with gifts, flowers (especially roses), and sweet treats.

Couples often plan romantic dinners or getaways, while singles might treat themselves to self-care or hang out with friends.

It’s a day to express feelings, share love, and make memories, and that’s exactly what Indunil Kaushalya Dissanayaka, of Cuteefly fame, is working on.

She has come up with a novel way of making that special someone extra special on Valentine’s Day.

Indunil is known for her scented and beautifully turned out candles, under the brand name Cuteefly, and we highlighted her creativeness in The Island of 27th November, 2025.

She is now working enthusiastically on her Valentine’s Day candles and has already come up with various designs.

“What I’ve turned out I’m certain will give lots of happiness to the receiver,” said Indunil, with confidence.

In addition to her own designs, she says she can make beautiful candles, the way the customer wants it done and according to their budget, as well.

Customers can also add anything they want to the existing candles, created by Indunil, and make them into gift packs.

Customers can also add anything they want to the existing candles, created by Indunil, and make them into gift packs.

Another special feature of Cuteefly is that you can get them to deliver the gifts … and surprise that special someone on Valentine’s Day.

Indunil was originally doing the usual 9 to 5 job but found it kind of boring, and then decided to venture into a scene that caught her interest, and brought out her hidden talent … candle making

And her scented candles, under the brand ‘Cuteefly,’ are already scorching hot, not only locally, but abroad, as well, in countries like Canada, Dubai, Sweden and Japan.

“I give top priority to customer satisfaction and so I do my creative work with great care, without any shortcomings, to ensure that my customers have nothing to complain about.”

“I give top priority to customer satisfaction and so I do my creative work with great care, without any shortcomings, to ensure that my customers have nothing to complain about.”

Indunil creates candles for any occasion – weddings, get-togethers, for mental concentration, to calm the mind, home decorations, as gifts, for various religious ceremonies, etc.

In addition to her candle business, Indunil is also a singer, teacher, fashion designer, and councellor but due to the heavy workload, connected with her candle business, she says she can hardly find any time to devote to her other talents.

Indunil could be contacted on 077 8506066, Facebook page – Cuteefly, Tiktok– Cuteefly_tik, and Instagram – Cuteeflyofficial.

-

Opinion7 days ago

Opinion7 days agoSri Lanka, the Stars,and statesmen

-

Business6 days ago

Business6 days agoHayleys Mobility ushering in a new era of premium sustainable mobility

-

Business3 days ago

Business3 days agoSLIM-Kantar People’s Awards 2026 to recognise Sri Lanka’s most trusted brands and personalities

-

Business6 days ago

Business6 days agoAdvice Lab unveils new 13,000+ sqft office, marking major expansion in financial services BPO to Australia

-

Business6 days ago

Business6 days agoArpico NextGen Mattress gains recognition for innovation

-

Business5 days ago

Business5 days agoAltair issues over 100+ title deeds post ownership change

-

Editorial6 days ago

Editorial6 days agoGovt. provoking TUs

-

Business5 days ago

Business5 days agoSri Lanka opens first country pavilion at London exhibition