Midweek Review

Rightwing economics or centre-left Opposition?

By Dr. DAYAN JAYATILLEKA

The situation is ripe for a progressive, social democratic, centre-left Opposition with necessarily populist appeal, but can there be one if an archaic, conservative, rightist economic theory is propounded as an alternative to the government’s oligarchic crony-capitalism?

How can the main Opposition party become a truly progressive-centrist formation which can be a magnet for voters from the vast bloc that voted for the Rajapaksas/Pohottuwa? What must it do?

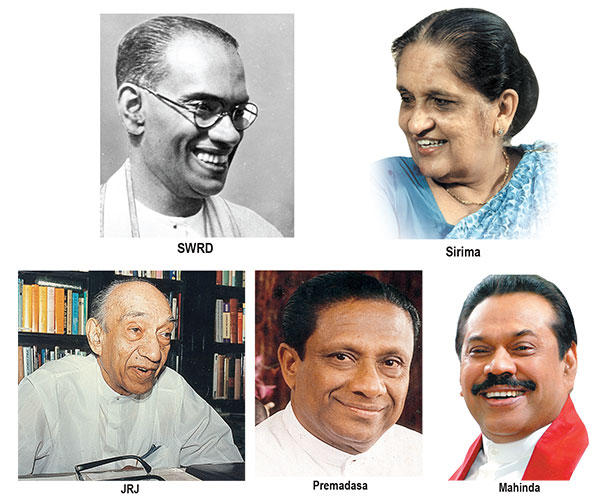

The answer to that is clear and simple, and it isn’t mine. Thirty years ago, the UNP held power at the Presidential, Parliamentary and Pradesheeya Sabha levels, i.e., executive, legislative and local authority levels. That was the last time it did so. The leader responsible for that achievement made a typically unorthodox and fascinating remark while addressing his last May Day rally in 1992, at Galle Face, a year before he was assassinated by a Tiger suicide-bomber. Ranasinghe Premadasa made a surprising and pointed reference to SWRD Bandaranaike:

“…The late Prime Minister SWRD Bandaranaike…left the UNP and formed the Sri Lanka Freedom Party because he thought that his views cannot be implemented through the UNP. If one were to take into account the changes that have taken place in the UNP between then and now, I am sure that if he were still alive, he would have rejoined the UNP…When you look at it from that point of view, you will be able to guess which May Day rally he would have attended if he were alive—the rally at Galle Face or the one at Campbell Park.” (President Premadasa: His Vision and Mission, Selected Speeches, p 192)

What Premadasa says here is that SWRD Bandaranaike with the progressive, moderate nationalist, centre-left views (the SLFP’s founding document used the definition ‘social democratic’) he held at the time he ruptured with the UNP because he thought they could not be accommodated, would have felt compelled and comfortable enough to rejoin the UNP because it had been transformed so radically as to be able to accommodate and represent such personalities and perspectives.

Translated into today’s politics, it can be understood as an injunction to the post-UNP successor party (led by Premadasa’s son) to be a party so configured that it can win over the voters and personalities of the progressive centre, the moderate nationalists, by representing their ideology, sentiments and grievances. In short, an Opposition party capable of winning over the centre-left SLFP and SLPP voters; the Rajapaksa voters.

JR-Ranil or Premadasa?

The ongoing and deepening economic crisis is tailor-made for a ‘Premadasist’ intervention, for three reasons:

(a) Globally, the Covid-19 pandemic has been acknowledged as proving the need for more investment in public goods and social infrastructure, rather than rely on the ‘magic of the marketplace’ with its profit motive.

(b) President Premadasa demonstrated that even in a context of extreme crisis, is it practically possible to revive economic growth, increase industrial exports and foreign investment while simultaneously, not sequentially, transferring real income to the poorest, increasing the real wages of the people and reducing inequality.

(c) The Opposition is led by his only son. It would be as absurdly incongruous for an Opposition party, led by President Ranasinghe Premadasa’s son not to adopt the Premadasa development paradigm and policy as it would be someday for an Opposition party led by Namal Rajapaksa, not to have his father Mahinda Rajapaksa’s as symbol, his achievements as template, and Mahinda Chinthanaya as the basis of its guiding ideology.

The problem is that there is an ideological inclination on the part of some in society and Opposition politics, to ignore the Premadasa development model and philosophy, pat him on the back for ‘reforms’, and elevate instead, rightwing economic doctrines. In international terms these are the economic ideas that President George HW Bush (Bush Sr.), a moderate Republican, derided as “voodoo economics”.

The UNP never won a Presidential election, won only two parliamentary elections, 15 years apart, with never a second consecutive term in governmental office, after it dumped the Premadasa development paradigm and shifted to neoliberal economics, or shifted back to the pre-Premadasa economic model which helped cause the Southern uprising.

With its leadership and Presidential candidate who did far better in November 2019 than the party did before (Feb 2018) or since, the post-UNP Opposition is more organically suited for a frankly neo-Premadasist strategy for economic revival and social upliftment, which the current crisis demands.

JR+BR?

A slightly surreal slogan was tweeted recently, claiming that “we need JR+Shenoy reform once again”. This relates to the ideas of rightwing economist BR Shenoy who produced a pamphlet in 1966 which was adopted as a policy platform by JR Jayewardene, then a Minister in the Dudley Senanayake Cabinet of 1965-’70.

This policy perspective is wrong headed several times over, starting with the contextual fact that the JR+Shenoy platform was not conceived as alternative to the parental precursor of the current Rajapaksa government’s policies, namely the Sirimavo Bandaranaike-NM Perera policies of the coalition government of 1970-’77.

The JRJ-Shenoy policy doctrine was one corner of an intra-governmental UNP policy debate in the mid-1960s. Today it is being revived at the second corner of a bipolar patterning of policy discourse, i.e., in an unhealthy polarisation.

Shenoy Syndrome

As a precocious lad who spent time in the editorial offices of Lake House and hung out with my father and his journalist colleagues and buddies, I was quite aware of the Shenoy episode real-time, because BR Shenoy was tapped, and his product promoted, by Esmond Wickremesinghe, the Managing Director of Lake House (and Ranil’s father). That episode was part of a policy debate that rocked the UNP government of Prime Minister Dudley Senanayake in 1965-1970.

Far from being the antipode of the statist closed economy of the Sirimavo regime, the JR+Shenoy (actually JR+Esmond+Shenoy) platform squarely targeted the genuinely liberal-welfarist economics of the PM Dudley Senanayake and his Planning Ministry tzar, Dr Gamini Corea.

It is absurd and dangerous to exalt the JR+BR Shenoy line today, when the logic of the Dudley Senanayake-Gamani Corea response at that time has been tragically validated by our political history: “It is wiser to spend on welfare, than to cut welfare and have to spend much more on military expenditure later.”

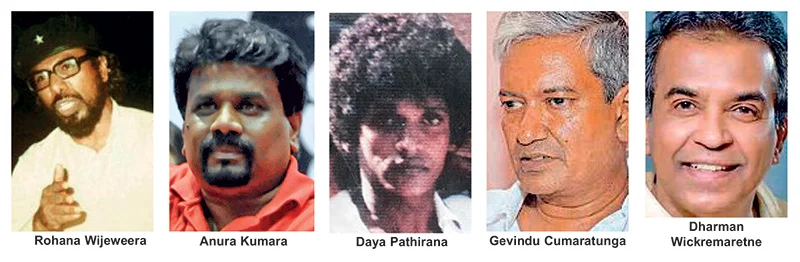

As the John Attygalle Report (he was the IGP, but the report was co-authored by D.I.G Ana Seneviratne) on the pre-1971 JVP revealed, and the statements of the accused in the main trial of the Criminal Justice Commission (CJC) confirmed, the movement was founded for armed revolution partly as a response to the ideological struggle within the UNP government. Rohana Wijeweera’s view was that the JR Jayewardene-BR Shenoy project would require the ouster of the Senanayake faction, the installation of an Indonesian style dictatorship, and the scrapping of national elections scheduled for 1970.

This was not as wildly outlandish as it seemed. The Indonesian coup and massacre had taken place in September 1965. Esmond Wickremesinghe and those who backed the JR+Shenoy programme against Senanayake liberal-welfarism, were applauding the post-coup Indonesian economic model. My father Mervyn de Silva had been in Indonesia (with his wife and son) at the invitation of President Sukarno’s Foreign Minister Dr. Subandrio for the celebration by Afro-Asian journalists of the 10th anniversary of the Bandung conference virtually on the eve of the coup. Mervyn was the last foreign journalist to interview DN Aidit, leader of the PKI (the non-violent Indonesian Communist Party) who was murdered by the Army a few months later while in hiding, unarmed. My father was among the few (I’m being generous here) in the Lake House press writing against the Indonesian coup and the massacre of 1965, while “the Indonesian model” was being promoted.

Coiled for armed resistance to a dictatorship which never came at the hands of the UNP Right identified as JRJ and Esmond Wickremesinghe equipped with the BR Shenoy agenda, the JVP uncoiled uncontrollably on the watch of the elected successor government, the SLFP-led UF coalition in 1971.

It is not that today’s JVP or FSP is dabbling in any way with violent resistance or ever likely to, but a worker-peasant-student social movement radicalised by the policies and political culture of the Gotabaya presidency, has grown to almost the same capacity as in the 1960s, and if ‘JR+Shenoy’ economic policies are followed after the Rajapaksa regime is inevitably turfed-out, the social explosion will occur no less inevitably on the watch of the incoming ex-UNP administration.

Development Debate

Today’s Lankan economic neoliberals (who call themselves ‘economic liberals’) target a giant of Third World economic thinking, Raul Prebisch. The bridge to the tradition of Prebisch, and indeed the great Ceylonese contribution to the global economic debate, was not the Sirimavo Bandaranaike-NM Perera regime, but rather, those who had been the targets of JRJ and Shenoy in the policy debate within the UNP of 1965-1970: the liberal-welfarist progressives of the Planning Ministry under Prime Minister Dudley Senanayake, namely Dr. Gamani Corea and his deputy, Godfrey Gunatilleke.

In the 1970s, the Lankan node of ‘Third Worldist’ progressive development thinking was the MARGA Institute, which was targeted by the UF coalition government, especially the rightwing Minister Felix Dias Bandaranaike and the Communist Party.

The Gamani Corea-Godfrey Gunatilleke perspective that JRJ+BR Shenoy (plus Esmond Wickremesinghe) had targeted within the UNP government of 1965-1970 and eventually supplanted, found itself revived, revised and reaccommodated within the economic paradigm of Ranasinghe Premadasa.

Prime Minister Premadasa’s extempore remarks at the panel discussion on the sidelines of the UNGA 1980; his invocation of justice for the global South at the UNGA 1980 and the Nonaligned Conference in Harare 1986, are evidence of his commitment to the international tradition of development thinking which Dr. Gamani Corea was a giant of, but is reviled by today’s para-UNP economic neoliberals. (https://www.unmultimedia.org/avlibrary/asset/2114/2114561/)

It is hardly accidental that the founder-Chairperson of the Institute of Policy Studies (IPS), at its initiation by Finance Minister Ronnie de Mel and through the Premadasa Presidency, was Dr. Gamani Corea rather than an ‘economic libertarian’ or ‘classic economic liberal’.

Premadasa Project

The formula that ‘we need JR+Shenoy reform once again’ also overlooks the history of the evolution of policy within the UNP in the Opposition in 1970-1973. The Dudley Senanayake line was being eclipsed, the JRJ line was becoming dominant, but a third line was coming into view, which was to be validated by real history when the ‘JR+Shenoy’ paradigm was a causative factor of the civil war in the south.

This ‘third paradigm’ was Ranasinghe Premadasa’s, an early articulation of which was his 4th April 1973 address to the Colombo West Rotary Club. He was so committed to that speech (delivered several years before Susil Sirivardhana joined him) that he republished it in the ‘SAARC Summit special supplement’ of the Daily News during his Presidency, accompanied by an introduction in bold type which read: “The seeds of today’s concepts were sown years ago…President Ranasinghe Premadasa, then First Member of Parliament for Colombo Central was invited by the Colombo West Rotary Club to deliver an address on the topic ‘A Plan for Sri Lanka’ at a luncheon meeting of the Club. The speech was delivered when President Ranasinghe Premadasa was only an Opposition member of Parliament and portrays the vision of a young politician of what he thought was the best for Sri Lanka”.

That he chose to reproduce it in the SAARC special supplement (1991) indicates that this perspective is one he wanted the outside world to know about, and which he hoped to radiate in the region.

In April 1973, he wrestled with the same problem that the economy faces today– the crisis of foreign exchange and dependency—and gave an answer that is distinctively redolent of the Rooseveltian New Deal (his 1988 Presidential election manifesto was to be entitled ‘a New Vision, a New Deal’):

“…If the problems of foreign exchange, development and unemployment are to be satisfactorily tackled, a massive development venture has to be launched to provide the necessary infra-structure such as a network of roads, a network of electricity, a network of irrigation and a network of domestic water supply. With the launching of such a scheme large number of people could be gainfully employed. Together with development of the infrastructure the country’s agricultural and industrial ventures will automatically improve. As a result, foreign exchange could be conserved. People will get more money into their hands thus enabling them to purchase their requirements. The question of subsidies will eventually be eliminated. We can solve our problems. Scarcity of foreign exchange is no obstacle. To earn foreign exchange, we must increase production; to increase production we must develop our national resources, and if we are to develop our national resources, we must harness the human potential that we have in abundance. It is futile to go on bended knees to foreign countries begging for assistance…” (Republished as ‘People’s Participation in Government’, CDN Nov. 21, 1991.)

After the UNP victory of 1977 and the installation of ‘JR+Shenoy reforms’ the evidence of its downside piled up in the 1980s from the reports of various UN agencies which had replaced ‘classical liberal economics’ with indices of inequality, the physical quality of life index (PQLI) and later the Human Development report (HDR), under the intellectual impact of a global struggle for ‘Another Development’ (as it was conceptualized) in which Gamini Corea and Godfrey Gunatilleke were the foremost Sri Lankan figures.

Prime Minister Premadasa appointed the Warnasena Rasaputram Commission. Janasaviya was Premadasa’s response to the revelations of the Rasaputram Report. The hubris of the Open economy and the ‘JR +Shenoy reform’ model had evaporated with the bloody near-extermination of the UNP in the latter half of the 1980s by Sinhala youth from the South (just as Premadasa had predicted).

Open Economy, ‘Economic Democracy’

“If anything, I am for economic democracy” Premadasa told civil service legend Neville Jayaweera in a substantive interview given to the latter published as ‘Charter for Democracy’ (1990). For him, ‘economic democracy’ meant “turning the nation into one where ‘have-nots’ become ‘haves’”.

This was Premadasa’s perspective on the open economy:

“In a world of economic interdependence, those who are self-dependent grow in strength. We live in a world society. We cannot close ourselves off from the world. Yet, we must be free to live and develop as we wish to. We will provide all the conditions for economic growth in an open economy. But an open economy does not mean an economy dictated to by others. An open economy does not mean an economy run for the benefit of others. An open economy must first benefit Sri Lankans before it benefits outsiders.” (‘Address at the Inauguration of the Koggala Export Processing Zone’-June 14th 1991, in ‘President Premadasa: His Vision & Mission-Selected Speeches’, pp 89-92.)

The Premadasa economic philosophy, though partly based on the Open Economy, is not that of ‘JR+BR Shenoy reforms’ of 1977 still less of 1966. It is a different, far more progressive policy paradigm or economic episteme. It is Sri Lankan Social Democracy.

Midweek Review

Daya Pathirana killing and transformation of the JVP

JVP leader Somawansa Amarasinghe, who returned to Sri Lanka in late Nov, 2001, ending a 12-year self-imposed exile in Europe, declared that India helped him flee certain death as the government crushed his party’s second insurrection against the state in the ’80s, using even death squads. Amarasinghe, sole surviving member of the original politburo of the JVP, profusely thanked India and former Prime Minister V.P. Singh for helping him survive the crackdown. Neither the JVP nor India never explained the circumstances New Delhi facilitated Amarasinghe’s escape, particularly against the backdrop of the JVP’s frenzied anti-India campaign. The JVP has claimed to have killed Indian soldiers in the East during the 1987-1989 period. Addressing his first public meeting at Kalutara, a day after his arrival, Amarasinghe showed signs that the party had shed its anti-India policy of yesteryears. The JVPer paid tribute to the people of India, PM Singh and Indian officials who helped him escape.

By Shamindra Ferdinando

Forty years after the killing of Daya Pathirana, the third head of the Independent Student Union (ISU) by the Socialist Students’ Union (SSU), affiliated with the JVP, one-time Divaina journalist Dharman Wickremaretne has dealt with the ISU’s connections with some Tamil terrorist groups. The LTTE (Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam) hadn’t been among them, according to Wickremaretne’s Daya Pathirana Ghathanaye Nodutu Peththa (The Unseen Side of Daya Pathirana Killing), the fifth of a series of books that discussed the two abortive insurgencies launched by the JVP in 1971 and the early ’80s.

Pathirana was killed on 15 December, 1986. His body was found at Hirana, Panadura. Pathirana’s associate, Punchiralalage Somasiri, also of the ISU, who had been abducted, along with Pathirana, was brutally attacked but, almost by a miracle, survived to tell the tale. Daya Pathirana was the second person killed after the formation of the Deshapremi Janatha Vyaparaya (DJV), the macabre wing of the JVP, in early March 1986. The DJV’s first head had been JVP politburo member Saman Piyasiri Fernando.

Its first victim was H. Jayawickrema, Principal of Middeniya Gonahena Vidyalaya, killed on 05 December, 1986. The JVP found fault with him for suspending several students for putting up JVP posters.

Wickremaretne, who had been relentlessly searching for information, regarding the violent student movements for two decades, was lucky to receive obviously unconditional support of those who were involved with the SSU and ISU as well as other outfits. Somasiri was among them.

Deepthi Lamaheva had been ISU’s first leader. Warnakulasooriya succeeded Lamahewa and was replaced by Pathirana. After Pathirana’s killing K.L. Dharmasiri took over. Interestingly, the author justified Daya Pathirana’s killing on the basis that those who believed in violence died by it.

Wickremaretne’s latest book, the fifth of the series on the JVP, discussed hitherto largely untouched subject – the links between undergraduates in the South and northern terrorists, even before the July 1983 violence in the wake of the LTTE killing 12 soldiers, and an officer, while on a routine patrol at Thinnavely, Jaffna.

The LTTE emerged as the main terrorist group, after the Jaffna killings, while other groups plotted to cause mayhem. The emergence of the LTTE compelled the then JRJ government to transfer all available police and military resources to the North, due to the constant attacks that gradually weakened government authority there. In Colombo, ISU and Tamil groups, including the PLOTE (People’s Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam) enhanced cooperation. Wickremaretne shed light on a disturbing ISU-PLOTE connection that hadn’t ever been examined or discussed or received sufficient public attention.

In fact, EROS (Eelam Revolutionary Organisation of Students), too, had been involved with the ISU. According to the author, the ISU had its first meeting on 10 April, 1980. In the following year, ISU established contact with the EPRLF (Eelam People’s Revolutionary Liberation Front). The involvement of ISU with the PLOTE and Wickremaretne revealed how the SSU probed that link and went to the extent of secretly interrogating ISU members in a bid to ascertain the details of that connection. ISU activist Pradeep Udayakumara Thenuwara had been forcibly taken to Sri Jayewardenepura University where he was subjected to strenuous interrogation by SSU in a bid to identify those who were involved in a high profile PLOTE operation.

The author ascertained that the SSU suspected Pathirana’s direct involvement in the PLOTE attack on the Nikaweratiya Police Station, and the Nikaweratiya branch of the People’s Bank, on April 26, 1985. The SSU believed that out of a 16-member gang that carried out the twin attacks, two were ISU members, namely Pathirana, and another identified as Thalathu Oya Seneviratne, aka Captain Senevi.

The SSU received information regarding ISU’s direct involvement in the Nikaweratiya attacks from hardcore PLOTE cadre Nagalingam Manikkadasan, whose mother was a Sinhalese and closely related to JVP’s Upatissa Gamanayake. The LTTE killed Manikkadasan in a bomb attack on a PLOTE office, in Vavuniya, in September, 1999. The writer met Manikkadasan, at Bambapalitiya, in 1997, in the company of Dharmalingham Siddharthan. The PLOTE had been involved in operations in support of President Chandrika Bandaranaike Kumaratunga’s administration.

It was President Premadasa who first paved the way for Tamil groups to enter the political mainstream. In spite of some of his own advisors expressing concern over Premadasa’s handling of negotiations with the LTTE, he ordered the then Elections Commissioner Chandrananda de Silva to grant political recognition to the LTTE. The LTTE’s political wing PFLT (People’s Front of Liberation Tigers) received recognition in early December, 1989, seven months before Eelam War II erupted.

Transformation of ISU

The author discussed the formation of the ISU, its key members, links with Tamil groups, and the murderous role in the overall counter insurgency campaign during JRJ and Ranasinghe Premadasa presidencies. Some of those who had been involved with the ISU may have ended up with various other groups, even civil society groups. Somasiri, who was abducted along with Pathirana at Thunmulla and attacked with the same specialised knife, but survived, is such a person.

Somasiri contested the 06 May Local Government elections, on the Jana Aragala Sandhanaya ticket. Jana Aragala Sandhanaya is a front organisation of the Frontline Socialist Party/ Peratugaami pakshaya, a breakaway faction of the JVP that also played a critical role in the violent protest campaign Aragalaya against President Gotabaya Rajapaksa. That break-up happened in April 2012, The wartime Defence Secretary, who secured the presidency at the 2019 presidential election, with 6.9 mn votes, was forced to give up office, in July 2022, and flee the country.

Somasiri and Jana Aragala Sandhanaya were unsuccessful; the group contested 154 Local Government bodies and only managed to secure only 16 seats whereas the ruling party JVP comfortably won the vast majority of Municipal Councils, Urban Councils and Pradeshiya Sabhas.

Let us get back to the period of terror when the ISU was an integral part of the UNP’s bloody response to the JVP challenge. The signing of the Indo-Lanka accord, in late July 1987, resulted in the intensification of violence by both parties. Wickremaretne disclosed secret talks between ISU leader K.L. Dharmasiri and the then Senior SSP (Colombo South) Abdul Cader Abdul Gafoor to plan a major operation to apprehend undergraduates likely to lead protests against the Indo-Lanka accord. Among those arrested were Gevindu Cumaratunga and Anupa Pasqual. Cumaratunga, in his capacity as the leader of civil society group Yuthukama, that contributed to the campaign against Yahapalanaya, was accommodated on the SLPP National List (2020 to 2024) whereas Pasqual, also of Yuthukama, entered Parliament on the SLPP ticket, having contested Kalutara. Pasqual switched his allegiance to Ranil Wickremesinghe after Gotabaya Rajapaksa’s ouster in July 2022.

SSU/JVP killed K.L. Dharmasiri on 19 August, 1989, in Colomba Kochchikade just a few months before the Army apprehended and killed JVP leader Rohana Wijeweera. Towards the end of the counter insurgency campaign, a section of the ISU was integrated with the military (National Guard). The UNP government had no qualms in granting them a monthly payment.

Referring to torture chambers operated at the Law Faculty of the Colombo University and Yataro operations centre, Havelock Town, author Wickremaretne underscored the direct involvement of the ISU in running them.

Maj. Tuan Nizam Muthaliff, who had been in charge of the Yataro ‘facility,’ located near State Defence Minister Ranjan Wijeratne’s residence, is widely believed to have shot Wijeweera in November, 1989. Muthaliff earned the wrath of the LTTE for his ‘work’ and was shot dead on May 3, 2005, at Polhengoda junction, Narahenpita. At the time of Muthaliff’s assassination, he served in the Military Intelligence.

Premadasa-SSU/JVP link

Ex-lawmaker and Jathika Chinthanaya Kandayama stalwart Gevindu Cumaratunga, in his brief address to the gathering, at Wickremaretne’s book launch, in Colombo, compared Daya Pathirana’s killing with the recent death of Nandana Gunatilleke, one-time frontline JVPer.

Questioning the suspicious circumstances surrounding Gunatilleke’s demise, Cumaratunga strongly emphasised that assassinations shouldn’t be used as a political tool or a weapon to achieve objectives. The outspoken political activist discussed the Pathirana killing and Gunatilleke’s demise, recalling the false accusations directed at the then UNPer Gamini Lokuge regarding the high profile 1986 hit.

Cumaratunga alleged that the SSU/JVP having killed Daya Pathirana made a despicable bid to pass the blame to others. Turning towards the author, Cumaratunga heaped praise on Wickremaretne for naming the SSU/JVP hit team and for the print media coverage provided to the student movements, particularly those based at the Colombo University.

Cumaratunga didn’t hold back. He tore into SSU/JVP while questioning their current strategies. At one point a section of the audience interrupted Cumaratunga as he made references to JVP-led Jathika Jana Balawegaya (JJB) and JJB strategist Prof. Nirmal Dewasiri, who had been with the SSU during those dark days. Cumaratunga recalled him attending Daya Pathirana’s funeral in Matara though he felt that they could be targeted.

Perhaps the most controversial and contentious issue raised by Cumaratunga was Ranasinghe Premadasa’s alleged links with the SSU/JVP. The ex-lawmaker reminded the SSU/JVP continuing with anti-JRJ campaign even after the UNP named Ranasinghe Premadasa as their candidature for the December 1988 presidential election. His inference was clear. By the time Premadasa secured the presidential nomination he had already reached a consensus with the SSU/JVP as he feared JRJ would double cross him and give the nomination to one of his other favourites, like Gamini Dissanayake or Lalith Athulathmudali.

There had been intense discussions involving various factions, especially among the most powerful SSU cadre that led to putting up posters targeting Premadasa at the Colombo University. Premadasa had expressed surprise at the appearance of such posters amidst his high profile ‘Me Kawuda’ ‘Monawada Karanne’poster campaign. Having questioned the appearance of posters against him at the Colombo University, Premadasa told Parliament he would inquire into such claims and respond. Cumaratunga alleged that night UNP goons entered the Colombo University to clean up the place.

The speaker suggested that the SSU/JVP backed Premadasa’s presidential bid and the UNP leader may have failed to emerge victorious without their support. He seemed quite confident of his assertion. Did the SSU/JVP contribute to Premadasa’s victory at one of the bloodiest post-independence elections in our history.

Cumaratunga didn’t forget to comment on his erstwhile comrade Anupa Pasqual. Alleging that Pasqual betrayed Yuthukama when he switched allegiance to Wickremesinghe, Cumaratunga, however, paid a glowing tribute to him for being a courageous responder, as a student leader.

SSU accepts Eelam

One of the most interesting chapters was the one that dealt with the Viplawadi Janatha Vimukthi Peramuna/Revolutionary Janatha Vimukthi Peramuna (RJVP), widely known as the Vikalpa Kandaya/Alternative Group and the ISU mount joint campaigns with Tamil groups. Both University groups received weapons training, courtesy PLOTE and EPRLF, both here, and in India, in the run-up to the so-called Indo-Lanka Peace Accord. In short, they accepted Tamils’ right to self-determination.

The author also claimed that the late Dharmeratnam Sivaram had been in touch with ISU and was directly involved in arranging weapons training for ISU. No less a person than PLOTE Chief Uma Maheswaran had told the author that PLOTE provided weapons training to ISU, free of charge ,and the JVP for a fee. Sivaram, later contributed to several English newspapers, under the pen name Taraki, beginning with The Island. By then, he propagated the LTTE line that the war couldn’t be brought to a successful conclusion through military means. Taraki was abducted near the Bambalapitiya Police Station on the night of 28 April, 2005, and his body was found the following day.

The LTTE conferred the “Maamanithar” title upon the journalist, the highest civilian honour of the movement.

In the run up to the Indo-Lanka Peace Accord, India freely distributed weapons to Tamil terrorist groups here who in turn trained Sinhala youth.

Had it been part of the overall Indian destabilisation project, directed at Sri Lanka? PLOTE and EPRLF couldn’t have arranged weapons training in India as well as terrorist camps here without India’s knowledge. Unfortunately, Sri Lanka never sought to examine the origins of terrorism here and identified those who propagated and promoted separatist ideals.

Exactly a year before Daya Pathirana’s killing, arrangements had been made by ISU to dispatch a 15-member group to India. But, that move had been cancelled after law enforcement authorities apprehended some of those who received weapons training in India earlier. Wickremaretne’s narrative of the students’ movement, with the primary focus of the University of Colombo, is a must read. The author shed light on the despicable Indian destabilisation project that, if succeeded, could have caused and equally destructive war in the South. In a way, Daya Pathirana’s killing preempted possible wider conflict in the South.

Gevindu Cumaratunga, in his thought-provoking speech, commented on Daya Pathirana. At the time Cumaratunga entered Colombo University, he hadn’t been interested at all in politics. But, the way the ISU strongman promoted separatism, influenced Cumaratunga to counter those arguments. The ex-MP recollected how Daya Pathirana, a heavy smoker (almost always with a cigarette in his hand) warned of dire consequences if he persisted with his counter views.

In fact, Gevindu Cumaratunga ensured that the ’80s terror period was appropriately discussed at the book launch. Unfortunately, Wickremaretne’s book didn’t cause the anticipated response, and a dialogue involving various interested parties. It would be pertinent to mention that at the time the SSU/JVP decided to eliminate Daya Pathirana, it automatically received the tacit support of other student factions, affiliated to other political parties, including the UNP.

Soon after Anura Kumara Dissanayake received the leadership of the JVP from Somawansa Amarasinghe, in December 2014, he, in an interview with Saroj Pathirana of BBC Sandeshaya, regretted their actions during the second insurgency. Responding to Pathirana’s query, Dissanayake not only regretted but asked for forgiveness for nearly 6,000 killings perpetrated by the party during that period. Author Wickremaretne cleverly used FSP leader Kumar Gunaratnam’s interview with Upul Shantha Sannasgala, aired on Rupavahini on 21 November, 2019, to remind the reader that he, too, had been with the JVP at the time the decision was taken to eliminate Daya Pathirana. Gunaratnam moved out of the JVP, in April 2012, after years of turmoil. It would be pertinent to mention that Wimal Weerawansa-Nandana Gunatilleke led a group that sided with President Mahinda Rajapaksa during his first term, too, and had been with the party by that time. Although the party split over the years, those who served the interests of the JVP, during the 1980-1990 period, cannot absolve themselves of the violence perpetrated by the party. This should apply to the JVPers now in the Jathika Jana Balawegaya (JJB), a political party formed in July 2019 to create a platform for Dissanayake to contest the 2019 presidential election. Dissanayake secured a distant third place (418,553 votes [3.16%])

However, the JVP terrorism cannot be examined without taking into JRJ’s overall political strategy meant to suppress political opposition. The utterly disgusting strategy led to the rigged December 1982 referendum that gave JRJ the opportunity to postpone the parliamentary elections, scheduled for August 1983. JRJ feared his party would lose the super majority in Parliament, hence the irresponsible violence marred referendum, the only referendum ever held here to put off the election. On 30 July, 1983, JRJ proscribed the JVP, along with the Nawa Sama Samaja Party and the Communist Party, on the false pretext of carrying out attacks on the Tamil community, following the killing of 13 soldiers in Jaffna.

Under Dissanayake’s leadership, the JVP underwent total a overhaul but it was Somawansa Amarasinghe who paved the way. Under Somawansa’s leadership, the party took the most controversial decision to throw its weight behind warwinning Army Chief General (retd) Sarath Fonseka at the 2010 presidential election. That decision, the writer feels, can be compared only with the decision to launch its second terror campaign in response to JRJ’s political strategy. How could we forget Somawansa Amarasinghe joining hands with the UNP and one-time LTTE ally, the Tamil National Alliance (TNA), to field Fonseka? Although they failed in that US-backed vile scheme, in 2010, success was achieved at the 2015 presidential election when Maithripala Sirisena was elected.

Perhaps, the JVP took advantage of the developing situation (post-Indo-Lanka Peace Accord), particularly the induction of the Indian Army here, in July 1987, to intensify their campaign. In the aftermath of that, the JVP attacked the UNP parliamentary group with hand grenades in Parliament. The August 1987 attack killed Matara District MP Keerthi Abeywickrema and staffer Nobert Senadheera while 16 received injuries. Both President JRJ and Prime Minister Ranasinghe Premadasa had been present at the time the two hand grenades were thrown at the group.

Had the JVP plot to assassinate JRJ and Premadasa succeeded in August 1987, what would have happened? Gevindu Cumaratunga, during his speech also raised a very interesting question. The nationalist asked where ISU Daya Pathirana would have been if he survived the murderous JVP.

Midweek Review

Reaping a late harvest Musings of an Old Man

I am an old man, having reached “four score and five” years, to describe my age in archaic terms. From a biological perspective, I have “grown old.” However, I believe that for those with sufficient inner resources, old age provides fertile ground to cultivate a new outlook and reap a late harvest before the sun sets on life.

Negative Characterisation of Old Age

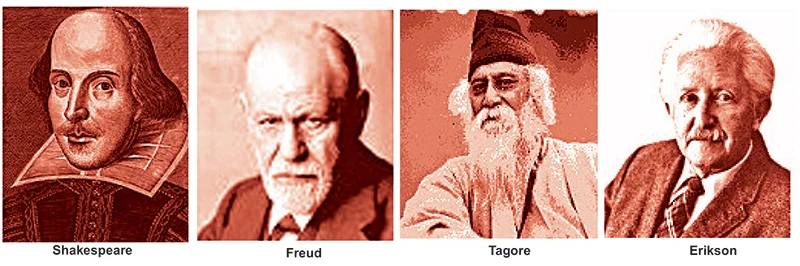

My early medical education and training familiarised me with the concept of biological ageing: that every living organism inevitably undergoes progressive degeneration of its tissues over time. Old age is often associated with disease, disability, cognitive decline, and dependence. There is an inkling of futility, alienation, and despair as one approaches death. Losses accumulate. As Shakespeare wrote in Hamlet, “When sorrows come, they come not single spies, but in battalions.” Doctors may experience difficulty in treating older people and sometimes adopt an attitude of therapeutic nihilism toward a life perceived to be in decline.

Categorical assignment of symptoms is essential in medical practice when arriving at a diagnosis. However, placing an individual into the box of a “geriatric” is another matter, often resulting in unintended age segregation and stigmatisation rather than liberation of the elderly. Such labelling may amount to ageism. It is interesting to note that etymologically, the English word geriatric and the Sanskrit word jara both stem from the Indo-European root geront, meaning old age and decay, leading to death (jara-marana).

Even Sigmund Freud (1875–1961), the doyen of psychoanalysis, who influenced my understanding of personality structure and development during my psychiatric training, focused primarily on early development and youth, giving comparatively little attention to the psychology of old age. He believed that instinctual drives lost their impetus with ageing and famously remarked that “ageing is the castration of youth,” implying infertility not only in the biological sense. It is perhaps not surprising that Freud began his career as a neurologist and studied cerebral palsy.

Potential for Growth in Old Age

The model of human development proposed by the psychologist Erik Erikson (1902–1994), which he termed the “eight stages of man,” is far more appealing to me. His theory spans the entire life cycle, with each stage presenting a developmental task involving the negotiation of opposing forces; success or failure influences the trajectory of later life. The task of old age is to reconcile the polarity between “ego integrity” and “ego despair,” determining the emotional life of the elderly.

Ego integrity, according to Erikson, is the sense of self developed through working through the crises (challenges) of earlier stages and accruing psychological assets through lived experience. Ego despair, in contrast, results from the cumulative impact of multiple physical and emotional losses, especially during the final stage of life. A major task of old age is to maintain dignity amidst such emotionally debilitating forces. Negotiating between these polarities offers the potential for continued growth in old age, leading to what might be called a “meaningful finish.”

I do not dispute the concept of biological ageing. However, I do not regard old age as a terminal phase in which growth ceases and one is simply destined to wither and die. Though shadowed by physical frailty, diminishing sensory capacities and an apparent waning of vitality, there persists a proactive human spirit that endures well into late life. There is a need in old age to rekindle that spirit. Ageing itself can provide creative opportunities and avenues for productivity. The aim is to bring life to a meaningful close.

To generate such change despite the obstacles of ageing — disability and stigmatisation — the elderly require a sense of agency, a gleam of hope, and a sustaining aspiration. This may sound illusory; yet if such illusions are benign and life-affirming, why not allow them?

Sharon Kaufman, in her book The Ageless Self: Sources of Meaning in Late Life, argues that “old age” is a social construct resisted by many elders. Rather than identifying with decline, they perceive identity as a lifelong process despite physical and social change. They find meaning in remaining authentically themselves, assimilating and reformulating diverse life experiences through family relationships, professional achievements, and personal values.

Creative Living in Old Age

We can think of many artists, writers, and thinkers who produced their most iconic, mature, or ground-breaking work in later years, demonstrating that creativity can deepen and flourish with age. I do not suggest that we should all aspire to become a Monet, Picasso, or Chomsky. Rather, I use the term “creativity” in a broader sense — to illuminate its relevance to ordinary, everyday living.

Endowed with wisdom accumulated through life’s experiences, the elderly have the opportunity for developmental self-transformation — to connect with new identities, perspectives, and aspirations, and to engage in a continuing quest for purpose and meaning. Such a quest serves an essential function in sustaining mental health and well-being.

Old age offers opportunities for psychological adaptation and renewal. Many elders use the additional time afforded by retirement to broaden their knowledge, pursue new goals, and cultivate creativity — an old age characterised by wholeness, purpose, and coherence that keeps the human spirit alive and growing even as one’s days draw to a close.

Creative living in old age requires remaining physically, cognitively, emotionally, and socially engaged, and experiencing life as meaningful. It is important to sustain an optimistic perception of health, while distancing oneself from excessive preoccupation with pain and trauma. Positive perceptions of oneself and of the future help sustain well-being. Engage in lifelong learning, maintain curiosity, challenge assumptions — for learning itself is a meaning-making process. Nurture meaningful relationships to avoid disengagement, and enter into respectful dialogue, not only with those who agree with you. Cultivate a spiritual orientation and come to terms with mortality.

The developmental task of old age is to continue growing even as one approaches death — to reap a late harvest. As Rabindranath Tagore expressed evocatively in Gitanjali [‘Song Offerings’], which won him the Nobel Prize:: “On the day when death will knock at thy door, what wilt thou offer to him?

Oh, I will set before my guest the full vessel of my life — I will never let him go with empty hands.”

by Dr Siri Galhenage

Psychiatrist (Retired)

[sirigalhenage@gmail.com]

Midweek Review

Left’s Voice of Ethnic Peace

Multi-gifted Prof. Tissa Vitarana in passing,

Leaves a glowing gem of a memory comforting,

Of him putting his best foot forward in public,

Alongside fellow peace-makers in the nineties,

In the name of a just peace in bloodied Sri Lanka,

Caring not for personal gain, barbs or brickbats,

And for such humanity he’ll be remembered….

Verily a standard bearer of value-based politics.

By Lynn Ockersz

-

Life style6 days ago

Life style6 days agoMarriot new GM Suranga

-

Business5 days ago

Business5 days agoMinistry of Brands to launch Sri Lanka’s first off-price retail destination

-

Features6 days ago

Features6 days agoMonks’ march, in America and Sri Lanka

-

Features6 days ago

Features6 days agoThe Rise of Takaichi

-

Features6 days ago

Features6 days agoWetlands of Sri Lanka:

-

News6 days ago

News6 days agoThailand to recruit 10,000 Lankans under new labour pact

-

News6 days ago

News6 days agoMassive Sangha confab to address alleged injustices against monks

-

Sports1 day ago

Sports1 day agoOld and new at the SSC, just like Pakistan